Worldwide precedent of COVID-19

On December 31st, 2019, in the city of Wuhan, China the first cases of patients infected with the SARS-CoV-2 (Covid-19) virus were detected. This novel virus belongs to the subfamily of Orthocoronavirinae, genus Coronavirus and subgenus Sarbecovirus (beta-coronavirus, beta-2b), and within it, to clade or lineage 2, which is, genetically, much closer to the coronavirus of bats than to the human SARS. The genome of the SARS-CoV-2 is formed by a single-stranded RNA with about 30,000 nucleotides and 6 ORF (open reading frames), identical to the rest of the coronaviruses, and several additional genes (Reina, 2020) (Additional information in the paper by Hernán García in the first section of this special number. Editor’s Note). SARS-CoV-2 causes COVID-19, a very contagious disease that expresses a high lethality, depending on risk factors such as chronic metabolic, respiratory and cardiovascular diseases (see Ikuri Álvarez, Section 1, Special Number). The disease may cause symptomatic or asymptomatic clinical profiles (Cantillo-Acosta and Sánchez-Fernández, 2020). The World Health Organization (WHO) declared a COVID-19 pandemic in March of 2020, indicating governments, people and companies to take immediate and effective action to mitigate and prevent a health emergency. Health systems and people play a crucial part in the minimization of the probabilities of infection-transmission and in reducing the impact on the economy and society.

The adoption of early, bold and efficient measures is expected to reduce short-term risks for employees and long-term costs for companies, the economy and society (www.who.int). In February, 2021 there are over 100 million confirmed cases of people infected with COVID-19, causing over 2 million deaths worldwide, which has been an enormous challenge for the WHO and the health systems in different countries, particularly in developing nations (www.who.int). At the moment of writing this paper, the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases had risen to 240.6 million and 4.8 million deaths (Editor’s Note). Currently, the world population and their governments are facing the challenge of the COVID-19 pandemic and all it represents, from an etiological, epidemiological and clinical point of view. There are no specific antivirals; the vaccine is still not being used in all countries and therefore the classic epidemiological recommendations (confinement, monitoring and follow-up) will help face this pandemic (Reina, 2020). By the first trimester of 2021, the WHO has approved the Pfizer/BioNTech, AstraZeneca/Oxford, Janssen, Moderna and Sinopharm vaccinations, all of which were developed at an unprecedented speed (Editor’s note).

The context of COVID-19 in Costa Rica

The first case of COVID-19 in Costa Rica was confirmed on March 6th, 2020. Straight away, the Ministry of Health of Costa Rica, along with the National Commission for the Prevention of Hazards and Attention to Emergencies, declared a state of yellow alert throughout the country and with this, the Executive Decree 42227-MP-S was issued on March 16th, 2020, by Carlos Alvarado Quesada, President of the Republic of Costa Rica; Silvia Lara Povedano, Minister to the Presidency, and Daniel Salas Peraza, Minister of Health (www.presidencia.go.cr). In this context, a great challenge is presented to universities, and particularly to those in which in-person attendance and practice are extremely important, such as in the case of Agronomy. Due to the high spread and infection rates of most of the variants of the virus, the measures taken include social distancing and the restriction of social activities. In this context, the higher education institutions in Costa Rica, such as the Universidad Nacional, have presented strategies to modify academic activities during the COVID-19 emergency, making it an opportunity to develop and implement new educational and didactic ways.

This article will review the regulations and initiatives taken for the bachelor’s level studies in the Universidad Nacional de Costa Rica (UNA), specifically in the plant pathology courses in the career of Agronomic Engineering and some possibilities of generalization in the country. A bibliographical search was carried out in presidential decrees, UNA University Council agreements, regulations and instructions of the Academic Vice-Chancellor of the UNA and other agreements and regulations of the Universidad Nacional.

Digital Contingency Plan in the UNA

The regulations of the UNA regarding teaching-learning processes in the area of Agronomy have materialized into 2 important strategies: the suspension of in-person teaching activities in 2020 and the virtual or bimodal activity to continue with teaching activities via technological platforms. The preventive regulations for the temporary suspension of lessons in public and private educational centers, including universities, by the Ministry of Health of Costa Rica, led the Academic Council of the Universidad Nacional of Costa Rica to issue the agreement UNA-CONSACA-ACUE-045-2020 on March 20th, 2020, with which the implementation of the Contingency Plan is approved for in-presence and/or remote technologically assisted lessons (www.consaca.una.ac.cr). The Contingency Plan had an immediate effect on the plant pathology education process and displayed the strengths and weaknesses of a traditional, classroom- and laboratory-based education system in which digital technology did not have a predominant place. Because of this pandemic, educational institutions and faculty members have had to urgently resort to technological resources to carry out the didactic mediation processes.

Thus, in 2020, different actions were carried out in the UNA to guarantee the continuity of teaching activities by migrating courses to a virtually assisted realm. This implied the definition of strategies to adjust course programs. Education via technological media is a challenge for teachers and students, due to certain conditions required for their applications, such as:

Availability of Internet connectivity. Implications in cost and reliability.

Adequate environment for academic work at home.

Adequate use of virtual platforms by teachers and students.

Ability of teachers to adjust and teach courses virtually.

Existence of academic digital technology support in the university.

The UNA has technological platforms and resources to contribute to the transformation of university education and to the development of the teaching-learning process with the use of Communication and Information Technologies (CIT), which were implemented or optimized during the phase of the ongoing pandemic: institutional virtual classroom, institutional email, Dropbox, delivery of printed material, Facebook, Google forms, Google docs, Classroom, Drive, Meet, Hangouts, Microsoft office 365, Microsoft Teams, One Drive, Skype, WhatsApp, YouTube and Zoom. Each one of these technological resources is free of cost for all faculty members and students.

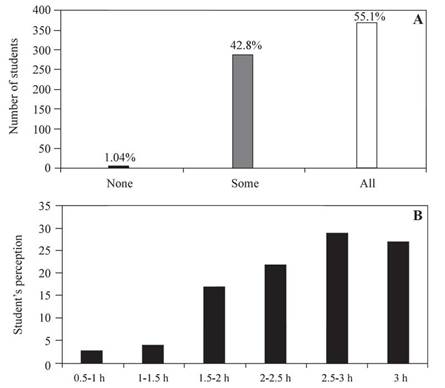

In addition, the UNA established a technological integration model in university education as a cornerstone to implement the integration of digital technological resources in teaching and to contribute towards forming human resources with the knowledge and dexterity required for an appropriate professional development. In the same year, a survey was held among the students of the Facultad de Ciencias de la Tierra y el Mar (School of Earth and Ocean Sciences - FCTM), of which the Escuela de Ciencias Agrarias (School of Agrarian Science) is a part, and where Agronomic Engineering is taught. Fifty one percent of the FCTM students surveyed attended all lectures online or synchronically, 42.8% attended some lectures, and a small part, 1%, did not attend any virtual lectures (Figure 1). In terms of the duration of virtual lectures, 29% of the population expressed that they lasted between 2.3 and 3 hours, whereas 27.8% mentioned that they lasted over 3 hours. This type of analyses helped evaluate the potential of the technological resources available and displayed the limitations of teaching-learning in a virtual environment.

Teaching Phytopathology in the UNA

In the realm of teaching plant Phytopathology, the COVID-19 pandemic has had an immediate effect on education, displaying strengths, opportunities, and weaknesses of the academy in which CIT is at its peak and with a central position in didactic education mediation processes. The virtual teaching of plant pathology has produced a great challenge for the faculty members. In addition, we acknowledge the effort made by the students to continue the educational process with this method.

Source: Department of Registration, UNA Costa Rica (www.registro.una.ac.cr).

Figure 1 A. Number and percentage of FCTM-UNA students that attended virtual lectures. B. Duration of virtual lectures according to the perception of students.

The professor has the obligation of reviewing the conditions of every student enrolled in the course and asking them about internet connectivity problems to carry out their remote activities. Likewise, access to the materials provided by the faculty members had to be guaranteed. Among the main adjustments made are the development of easy-access and immediate communication tools such as the application WhatsApp, video recording, tutorials of routine lab procedures such as the isolation of fungi, bacteria from plant and soil tissues, digitally sending material such as lab manuals or digital didactic guides. In addition, lectures were held via virtual platforms.

On the other hand, although some plant pathology thematic contents can be digitized, such as sampling methods, etiological studies, morphological characteristics of causal agents and disease management methods, the practice of learning by doing is always necessary. Students must be directly involved with lab procedures, field tours, sample processing and talking to farmers to understand the entire agricultural environment. One strategy was to implement the strategy ‘2020 Plant pathology, at a distance but together’ which can be read in María del Milagro Granados in this Section (Editor’s note)

In the ongoing lockdown situation, it has become necessary to carry out changes in the teaching-learning processes where different didactic learning mediation strategies are contemplated, but different to those usually used in the agricultural sphere. The sphere of plant pathology has solid theoretical bases with which it can be taught using traditional processes; however, more experience and methodology is still required in virtual realms. Virtual education seems to have an advantage over the in-person format. When the educational designs are accurate, the quality of digital learning is proven. The efficiency of these systems is, at least, like in-person systems. On the other hand, this article poses the debate on innovations and disruptive technologies, suggesting that digital education (new version of distance education) is supposing an educational disruption, since it contemplates a drastic change in supports and methods, and because it is gradually gaining ground over conventional formats (García-Aretio, 2017). Virtual didactic education mediation processes tend to favor interpersonal communication and the interaction is quick and can be carried out at any moment, which stimulates the ‘direct’ contact between teacher and student. However, in virtual realms, does away with the need to meet ‘face-to-face’ with fellow students, socialize, discuss, study together as a group, all of which are elements that contribute to the comprehensive formation of citizens and which do not derive from the curriculum per se, but from the community and the universality of ideas represented by a university context. Likewise, virtual attendance has a greater flexibility in terms of movement and times, i.e., replacing the professor is much easier in this format, which in turn contributes to the timelessness and the destruction of the educational community (Ralón et al., 2004).

Advantages and Disadvantages of CIT in Virtual Education

Herrera-Añazco and Toro-Huamanchumo (2020) state that virtuality presents a series of advantages, although there are several limitations that must be analyzed in order to optimize the teaching-learning process in times of COVID19. The virtual teaching experience is summarized in Table 1. The updating and migration to digital platforms may imply a lengthy period and requires planning. One of the main problems was that, due to lockdown, the updating and adaptation of phytopathology practice activities requires creativity.

In 2020, many research centers, both public and private, were working at a distance, which made it difficult for students to attend these institutes in person to learn modern plant pathogen identification and handling techniques from experts. Despite this way of working at a distance, professors and researchers remained in contact via videoconferences in platforms such as Microsoft Teams and Zoom. The area of plant pathology diagnosis has needed to use virtual classrooms and different technological resources such as tutorials, videos, case studies and asynchronous virtual (personalized) and synchronous (group) activities to give the students the available opportunities and resources for an appropriate and competent education.

Table 1 Advantages and disadvantages of the teaching-learning process via CIT in virtual mode in response to lockdown policies and social distance due to COVID-19.

| Ventajas |

|---|

| - Disminuye la probabilidad de contagio por evitarse actividades presenciales |

| - Evita gasto de las Universidades en equipos de protección personal |

| - Facilita la ‘entrega’ de materiales en tiempo real mediante diferentes medios digitales |

| - Actualiza a los docentes en entornos virtuales, i.e. TIC |

| - Evita el desplazamiento a centros de estudios debido al confinamiento |

| - Pueden integrarse clases/conferencias con docentes nacionales y/o internacionales |

| - Puede integrarse al curso eventos científicos nacional o internacionales |

| Desventajas |

| - No todas las universidades tienen plataformas virtuales robustas y soporte técnico. |

| - Docentes pueden estar renuentes al cambio a modalidad virtual |

| - Requiere motivación tanto de profesores como alumnos |

| - Recargo atemporal de tareas y funciones |

| - No todos los estudiantes tienen acceso a equipo tecnológico |

| - Limitada experiencia en enseñanza-aprendizaje virtual |

| - Limita retroalimentación en tiempo real y pérdida del contacto visual de conjunto. |

| - Comportamientos antiéticos (plagio, copia en evaluaciones). |

In the virtual active learning, the use of mobile apps such as Kahoot were implemented. In the flipped classroom, reading and videos were assigned through a platform for virtual group discussions. In ‘design thinking,’ experiments were held in labs, farms and students’ homes, using plants inoculated with pathogens known by the professor. The idea was that students tried to find the identity of the infectious process of the diseased plants using the techniques of isolation, identification, and diagnosis, which were reviewed in person in the laboratory before lockdown. In this way, the knowledge acquired was put into practice and students faced a real case belonging to their discipline as future agronomists. The main result of the academic innovation was the increased interest of students. Nowadays, students are not missing virtual lectures and there is an active participation within the teaching-learning process.

Perspectives

Optimizing the virtual teaching-learning process in plant pathology requires the articulation of three types of innovations:

Innovation at an institutional level, where policies are defined and decisions are made regarding the strategies to implement the discipline.

Curricular innovation to define the educational thematic structure and construction of strategies to gather information on the needs and demands of students, and vision of professors.

Didactic educational innovation: a) Didactic planning practices: creation of records, construction of models and definition of virtual processes; b) Virtual didactic intervention practices and selection of CIT for education; c) practices of evaluations of education with the design of instruments and the construction of virtual strategies.

Although the virtualization of the contents of plant pathology courses has become an alternative, like the possibility of sharing didactic videos of lab procedures or meetings through platforms to discuss specific cases and topics of phytopathological interest, these will not replace the learning of abilities that can only be obtained in the laboratory and on the fields. Virtuality as a product of the pandemic has allowed us to raise some questions:

Is it necessary and crucial to be physically present to teach plant pathology or other areas of agricultural science?

Can it presence be replaced by a virtual presence?

The continuous evolution of the digital technology is creating and setting a precedent in the traditional way of the teaching-learning processes. As a result of the pandemic, there is the hope of a narrowing digital gap and of an improvement of CIT applied to teaching-learning processes, allowing a greater versatility and access to remote areas.

Conclusions

The pandemic caused by COVID-19 has presented challenges in agricultural education, both worldwide and nationally, and continues to do so. The virtual teaching-learning process of plant pathology in Agronomy in the UNA is inevitable in Costa Rica during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. However, didactic educational strategies must be developed to ensure that students acquire the knowledge and abilities needed to tackle their professional challenges. This process with help lay the foundations of agronomic education in future health challenges, but also to promote models for university connections with society. Each university or institution has responded according to its possibilities to obtain the greatest benefits and knowledge from virtualization.

text in

text in