Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista mexicana de fitopatología

On-line version ISSN 2007-8080Print version ISSN 0185-3309

Rev. mex. fitopatol vol.38 n.3 Texcoco Sep. 2020 Epub Nov 27, 2020

https://doi.org/10.18781/r.mex.fit.2005-2

Scientific Articles

Interaction between Mycodiplosis and Hemileia vastatrix in three scenarios of coffee crop management (Coffea arabica)

1Universidad Autónoma Chapingo, Km 38.5 Carretera México-Texcoco, Chapingo, Estado de México. C.P. 56230. México.

2Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana. Unidad Xochimilco. Calzada del Hueso 1100, Colonia Villa Quietud, Delegación Coyoacán, C.P. 04960. México.

Coffee rust (Hemileia vastatrix) is a devastating disease for coffee plantations in Mexico. Control methods have focused on the use of fungicides, with no success, so biological control represents an alternative. Mycodiplosis larvae are reported as predators of H. vastatrix but the information available about this insect is limited. The objectives of this research were to describe the type of relationship between H. vastatrix and Mycodiplosis, and to know their distribution pattern in the plant canopy. Three plots with a high incidence of coffee rust in Xochitlán de Vicente Suárez, Puebla, were sampled and were registered periodically the severity of the rust and the number of larvae of Mycodiplosis per strata of the canopy. 25 plants per plot were selected, sampled in “cinco de oros”. Larvae were molecularly identified. Using the Kruskal Wallis test, differences were detected in the number of sampling sites in the severity of rust and the number of Mycodiplosis larvae, detecting a positive correlation between the severity of rust and the number of Mycodiplosis larvae. The Mycodiplosis distribution was similar in the strata (low, medium and high) of the evaluated plants.

Key words: Coffee rust; mycophagus; biological control; incidence; severity

La roya del cafeto (Hemileia vastatrix) es una enfermedad devastadora para los cafetales en México. Los métodos de control se han centrado en el uso de fungicidas, pero sin éxito, por lo que el control biológico representa una alternativa. Las larvas de Mycodiplosis se reportan como depredadoras de H. vastatrix, pero la información disponible sobre este insecto es limitada. Los objetivos de esta investigación fueron describir el tipo de relación entre H. vastatrix y Mycodiplosis y conocer su patrón de distribución en el dosel de la planta. Se eligieron tres plantaciones con incidencia de roya en Xochitlán de Vicente Suárez, Puebla y se registraron periódicamente la severidad de la roya y el número de larvas de Mycodiplosis por estrato de la planta. Se seleccionaron 25 plantas por parcela, muestreada en cinco de oros. Las larvas se identificaron molecularmente. Mediante la prueba de Kruskal Wallis, se encontraron diferencias significativas entre sitios de muestreo en la severidad de roya y el número de larvas de Mycodiplosis, detectando una correlación positiva entre la severidad de la roya y el número de larvas de Mycodiplosis. La distribución de Mycodiplosis fue similar en los estratos (baja, media y alta) de las plantas evaluadas.

Palabras clave: Roya del cafeto; micófago; control biológico; incidencia; severidad

Coffee rust is a disease caused by the basidiomycete Hemileia vastatrix (Uredinales: Pucciniaceae). Since 2012, this disease has been catalogued as destructive in Central America, since it has destroyed 30% of all coffee crop productions (Henderson, 2020). In Mexico, rust is present in all areas containing susceptible varieties, and a reduction has been registered in the production of cherry coffee since el 2012, when 1,336,882 t were produced, in comparison with 2018, in which 835,380 t were produced (SAGARPA-SENASICA 2016; SAGARPA-SIAP 2018).

The rust cycle begins with the deposition and germination of uredospores on the leaves; the infection depends on several environmental and physiological factors of the plant, although the main ones are the amount of rainfall, temperature, age of leaves and inoculant (Nutman and Roberts, 1963). Uredospores are scattered throughout a plantation by the wind or the splashing of rainwater (Nutman and Roberts, 1963; Rayner 1961; Arroyo et al., 2018). Rust reduces the photosynthetic ability of plants and the development of the new sprouts in the next planting cycle. A high severity one year will directly affect the production level of the following year, causing a gradual reduction in growth, which triggers defoliations, followed by the progressive death of sprouts and branches (CABI, 2018).

An alternative for the management of rust is the genetic resistance of the varieties. The hybrid Catimor and the variety Robusta have proven to be more tolerant to the disease than the variety Arabiga; however, tolerance is rarely effective against all the breeds of the pathogen (CABI, 2018). Regardless of the variety, in order to prevent or control this disease, fungicides based on copper compounds are frequently used to prevent or control this disease (Haddad et al., 2009; Loland and Singh, 2004). Nevertheless, these may bring problems to the ecosystem, since the copper accumulates in the soil and generates toxicity in the trophic chains when it accumulates in high concentrations (Loland and Singh, 2004). Late, isolated applications near to or after the harvesting season are inefficient for the control (Martínez et al., 2013). The use of some systemic fungicides is also recommended (Martínez et al., 2013); however, these products are not selective and will affect entomopathogenic fungi, such as Lecanicillium lecanii (Hypocreales: Cordycipitaceae), which help reduce coffee pest populations, such as green scale (Coccus viridis, Hemiptera: coccidae) (Jackson et al., 2012).

A recommended eco-friendly alternative for the management of any disease is the use of biological control agents. In this sense, mycophagus insects such as the larvae of the genus Mycodiplosis (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) (Kiel, 2014) feed off rust (Basidiomycota: Pucciniales) or mildew (Erysiphales) (Holz, 1970). The number of Mycodiplosis species that feed of rust spores, their frequency and distribution is unknown, since few studies have examined the relation between Mycodiplosis and the fungi they feed off (Kiel, 2014). M. hemileiae isbelieved to be a potential H. vastatrix biological control agent in Latin America and the Caribbean (Hajian-Forooshani et al., 2016). Kaushal et al. (2001) suggest that the relation helps host plants, since the larva reduces the amount of fungal spores. However, Kluth et al. (2001) suggest that diptera could function as dissemination agents of the fungus in the plant. Due to this, the aims of the present investigation were to: 1) Describe the type of relation between coffee rust (H. vastatrix) and Mycodiplosis spp. in three different crop management systems and 2) to know the distribution patterns of Mycodiplosis spp. and H. vastatrix in the canopy of the plant.

Materials And Methods

Sampling site. This investigation was carried out in the municipal area of Xochitlán de Vicente Suárez, Puebla, Mexico, in plots with coffee plants (Coffea arabiga) of diverse varieties (Costa Rica 95, Caturra, Colombiana and Borbón) and ages (10 to 35 years). Three plots were chosen, the first of which was located in Santa Lucia (19° 58’ 17” N; 97° 38’ 05” W), at 964 meters above sea level (masl). The second was located in Cuetzinapan (19° 58’ 39” N; 97° 38’ 08” W) at 930 masl and the third, in San Bernardo (19° 58’ 44” N; 97° 38’ 26” W) at 903 masl. In Santa Lucía, seven rounds of contact fungicides (copper oxychloride and copper sulfate pentahydrate) were applied, along with six of systemic fungicides (Cyproconazole, Epoxiconazole, Flutriazole and Azoxystrobin+Cyproconazole), two foliar fertilizations and four nitrogen fertilizations on the soil. In Cuetzinapan, only six rounds of contact fungicides (copper oxychloride and copper sulfate pentahydrate) were applied, along with three rounds of systemic fungicides (Cyproconazole, Epoxiconazole and Azoxystrobin+Cyproconazole), one foliar fertilization and three nitrogen fertilizations on the soil. No fungicide was applied in San Bernardo, but one round of foliar fertilization was applied, along with three nitrogen fertilizations on the soil. In all sites, phytosanitary and formation prunings were carried out.

Molecular identification of Mycodiplosis. The identification was performed with the molecular analysis of sequences on the mitochondrial COI gene, since the morphological description of adult males is necessary for the taxonomic characterization by the species (Henk et al., 2011) and gathering them on the field is complicated. Therefore, in each plot selected, five larvae were gathered, from the first to the last instar, in each coffee plant evaluated for severity. A total of 125 larvae were gathered, per plot, then placed in jars containing ethanol at 70%, labelled and transported to the laboratory in the Colegio de Postgraduados, Montecillo campus in Texcoco, State of Mexico.

The total DNA extraction was performed with 30 larvae in each site sampled. The larvae were rinsed three times in sterile distilled water to remove excess ethanol and later transfered to an Eppendorf tube containing CTAB at 2% + 1% of 2-Mercaptoethanol; they were macerated using a micropistile and incubated with K proteinase at 10% for 1 hour at 65 °C. The phases were separated using chloroform: isoamyl alcohol (24:1) and centrifuged for 15 minutes at 13000 rpm. For precipitation, recovered phase IV of ethanol at 100% was exposed for 30 minutes to a temperature of -20 °C. It was then centrifuged for 15 min at 13000 rpm to recover the tablet, which was dissolved in 30 µL of HPLC water. The concentration and integrity of the DNA was corroborated in a Nanodrop. For the PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction), the primers (HCO and LCO) were used, along with conditions of amplification described by Vrijenhoek (1994). These amplified a region of ⁓710 pairs of bases of the mitochondrial gene cytochrome C oxidase subunit I (COI). The PCR products of the expected weight were purified using the kit Wizard® and sent for sequencing to Macrogen® (Seoul, Korea). The sequences were cleaned using the program BioEdit, and compared with the data base available in the GenBank. The best sequence was uploaded onto this system to obtain the access number.

Evaluation of rust severity. In each plot, a 5-point sampling was carried out and five plants were marked in each point, for a total of 25 plants. The plant’s canopy was divided into three strata: low (< 40 cm), middle (41-80 cm) and high (>80 cm); three leaves were chosen at random from every stratum and evaluated individually with the scale developed by DGSV-SINAVEF-LANREF (2016) with modifications, where 0= healthy leaf without pustules, 1= 0.5-1% of surface with (more than one chlorotic spot on the leaf), 2= 1-5%, 3= 6-20%, 4= 21-50% and 5 >50%. In total, six evaluations were carried out, starting in July 2017 and ending in January 2019.

Evaluation of the number of Mycodiplosis larvae. This was carried out on the plants and leaves selected to evaluate the severity caused by the rust. Out of each previously selected leaf, the number of Mycodiplosis larvae was counted and recorded per leaf, to obtain a total of three measurements per stratum and nine for every marked plant. The evaluations were carried out at the same time as the measurement of rust severity.

Statistical analysis and determination of the relation between severity and number of larvae. Averages were compared with a non-parametric Kruskal Wallis test between the three sampling sites; the rust severity data were used, along with the number of Mycodiplosis larvae evaluated in the three strata of the plants (low, middle and high). A reliability of 95% and an alpha of 0.05% were considered. A spearman correlation analysis was carried out between the rust severity tests and Mycodiplosis to identify whether there is a tendency between the degree of infection and the number of larvae for each plant stratum (low, middle and high). The data were analyzed by sampling site using the program SAS JMP 11.0.

Results And Discussion

Identification of Mycodiplosis. The consensus sequence obtained was registered in the GenBank data base (accession number MK986689), and comparing it with other sequences, a 95% similarity was obtained with specimens of the Cecidomyiidae family. There is little information available in the data bases on Mycodiplosis species, and in general terms, it is a scarcely studied genus. The members of this genus are described by the morphology of adult males. There are 49 species described and deposited in the Natural History Museum of Jamaica and the United States of America. It is believed that a degree of specialization may exist between the species of Mycodiplosis and the species off of which they feed; although one same species has been found to feed off of different species of rust, such as M. rubida, which was described in Uromyces pisi (Pucciniales: pucciniaceae) and Puccinia sp. (Pucciniales: pucciniaceae). The degree of specialization between the Mycodiplosis species in uncertain (Nelsen, 2013).

The phylogenetic analysis carried out on this genus in 2013 was performed with larvae from 261 collections of plants, botanized and infected by fungi. This analysis did not contemplate any coffee plant infected with Hemileia vastatrix, (Nelsen, 2013). Further and more profound research is necessary in order to be able to describe the mycophagous species involved.

Evaluation of rust severity and number of Mycodiplosis larvae. The climate in Xochitlán de Vicente Suárez is classified as Cfa (subtropical humid), with an average temperature of 19.8 °C and annual rainfalls of around 3,293 mm (SMN-CNA, 2018). These conditions promote the development of rust, which is more severe in coffee plantations located at altitudes below 1500 masl, in warm temperatures and with prolonged periods of humidity (CABI, 2018); therefore, throughout the present investigation, the diseased always prevailed in the selected sites.

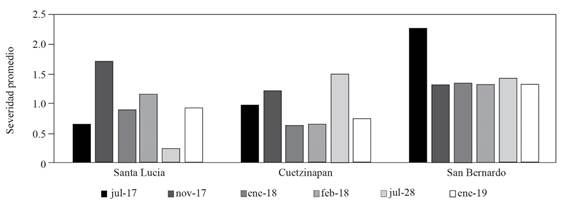

In Santa Lucia and Cuetzinapan, rounds of systemic fungicides were applied, unlike in San Bernardo, where no rounds were applied. The data show that the applications kept rust severity at lower levels than in places in which no chemical control was applied. Fungicides act directly on the intensity of sporulation and they limit the areas with uredospores (Merle et al., 2019). However, the fluctuation of the severity was greater in Santa Lucia and Cuetizapan, unlike in San Bernando, where it was stable (Figure 1). Additionally, rust severity was found to be similar in Cuetzinapan and in Santa Lucía, although less fungicide and fertilizer was applied in the former, indicating that the number of fungicide applications could be reduced without reducing the effectiveness of the control.

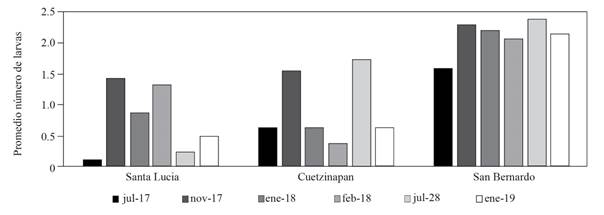

In regard to Mycodiplosis, the presence of larvae was also observed in all the evaluations performed, and the site with the highest population density was San Bernardo, while Cuetzinapan and Santa Lucía were similar (Figure 2). Given that the larvae of this diptera feed off of uredospores, it seems that, the higher their availability, the higher the number of larvae. However, greater evidence is required to determine if the functional response of larvae to the fluctuation of uredospores is not linear (Davies, 2007).

Severity and number of larvae. The Kruskall-Wallis analysis displayed significant differences between the sampling sites, in both severity (p<.0001) and in number of larvae (p<.0001) (Table 1). The plot located in San Bernardo had the highest severity and number of larvae, while the one in Cuetzinapan had the lowest severity and number of larvae (Figures 2 and 3). This is due to the applications of fungicides that helped reduce rust severity and, therefore, there was less food availability for larvae. Similar results were reported by Merle et al. (2019), who showed that its natural enemy (Lecanicillium lecanii) was also more abundant in areas with more rust.

Figure 1. Severity of coffee rust (Hemileia vastatrix) in three locations and six dates of sampling in the municipal area of Xochitlán de Vicente Suárez, Puebla.

We assume that in all areas, the population of the diptera helps reduce Hemileia vastatrix populations, since it feeds off the uredospores, which could delay the beginning of the infection or contribute to reducing initial infections (Nutman and Roberts, 1963). However, given that the level of severity is high, it would be necessary to explore whether an efficient management option is biological control by flooding.

Figure 2. Fluctuations in the population of Mycodiplosis spp. In three locations and six dates of sampling in the municipal area of Xochitlán de Vicente Suárez, Puebla.

The comparison of averages performed with the rust severity data per plant stratum (low, middle and high) showed significant differences (p<0.001). The severity in the middle stratum was determined to be greater than in the low and high strata (Table 2). This may be due to several factors, such as the layout of plant tissues, the amount of light/shade and the genotype and age of the plant. In general, the middle stratum has a greater amount of plant tissue, whereas the higher stratum is composed of new tissue or tissue in formation, and the lower stratum has a lower number of branches. Shade is different in the strata of the plant, and it is known to have antagonistic effects in the colonization and the sporulation of rust (Toniutti et al., 2017). In addition, the number of appressoria in the fungus decreases in susceptible genotypes as the leaves age, whereas in resistant genotypes, there are more appressoria in young and old leaves (Coutinho et al., 1994).

Table 1. Comparison between means of the severity and number of larvae (Mycodiplosis spp.) according to the strata of the plants and the sampling site in the municipal area of Xochitlán de Vicente Suárez, Puebla.

| Sitio | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Santa Lucia | Cuetzinapan | San Bernardo | ||||||

| Media | DE | Media | DE | Media | DE | X2, p | ||

| Severidad | Bajo | 0.95 | 1.19 | 0.97 | 1.24 | 1.49 | 1.58 | 28.89, <0.001 |

| Medio | 1.13 | 1.32 | 0.97 | 1.19 | 1.52 | 1.52 | 34.59, <0.001 | |

| Alto | 0.83 | 1.11 | 0.82 | 1.18 | 1.42 | 1.42 | 49.67, <0.001 | |

| Larvas | Bajo | 0.78 | 1.46 | 0.69 | 1.3 | 2.09 | 2.09 | 93.29, <0.001 |

| Medio | 0.91 | 1.79 | 0.9 | 2.24 | 2.11 | 2.11 | 105.9, <0.001 | |

| Alto | 0.72 | 1.25 | 0.68 | 1.31 | 2.32 | 2.32 | 121.6, <0.001 | |

X 2 derived from a Wilcoxon and Kruskall Wallis Test, SD= Standard Deviation.

No significant differences (p=0.2686) were found in the distribution of Mycodiplosis in the strata of the plant (Table 2). Merle et al. (2019) found that, in the strata of coffee plants, the area with uredospores was similar under the shade or in areas exposed to the sun, which reinforces the results obtained in the present investigation, since larvae had the same food availability in the three strata, therefore its distribution was similar.

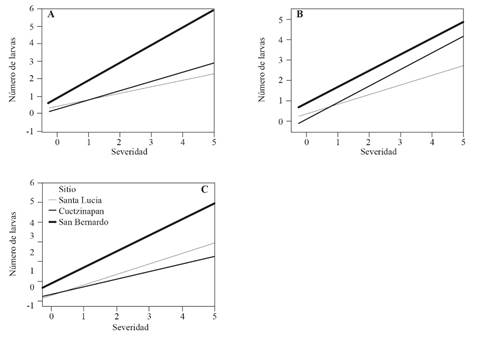

Correlation between Mycodiplosis and rust severity. A positive correlation was found in all sites and strata between rust severity and the number of Mycodiplosis larvae (Table 3). In San Bernardo there was a very clear positive tendency, in which a higher severity meant a greater number of larvae (Figure 3). In general terms, for all sites, the high stratum displayed a higher correlation. In San Bernardo, no fungicides were applied and this allowed for a better association between rust and Mycodiplosis. Copper-based fungicides not only affect rust directly, but also natural enemies and the phenology of the host plant (Brinate et al., 2015).

In diverse experiments, positive correlations have been found between hosts/prey and parasites/predators, similar to those observed in the present work. Such is the case of the different stages of the cycle of the mycophagous coccinelid Illeis cincta and the severity caused by mildew (Oidium sp.) in sunflower (Helianthus annuus) (Jagadish et al., 2017), or of the cell availability of the larva Trichoplusia ni and the multiplication of the entomopathogenic virus Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV) (Tseng and Myers, 2014).

Table 2. Distribution of the severity and number of larvae (Mycodiplosis spp.) according to the strata of the coffee plants sampled in the municipal area of Xochitlán de Vicente Suárez, Puebla.

| Bajo | Medio | Alto | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Media | DE | Media | DE | Media | DE | X2, p | |

| Severidad | 1.14 | 1.37 | 1.21 | 1.35 | 1.02 | 1.31 | 18.00, <0.001 |

| No. Larvas | 1.19 | 2.1 | 1.31 | 2.4 | 1.24 | 2.2 | 2.62, 0.2686 |

X 2 derived from a Wilcoxon and Kruskall Wallis Test, SD= Standard Deviation.

In the present investigation, the positive correlation between Mycodiplosis and the severity of rust can be analyzed from two perspectives: rust as a pathogenic agent of the coffee plant that depends on the availability of plant tissue and Mycodiplosis as a biocontrolling agent (predator) of rust, which depends on the number of uredospores available (prey).

The general conditions of the host have been observed, in various pathosystems, to beneficially or negatively affect the development of the parasite. In some cases, if the host is “low quality” and does not have ideal conditions, biotic and abiotic, for its development, the parasite will easily infect it and it will reproduce more, leading the population of the host to continue under non-ideal conditions, making it more and more susceptible, and therefore with a better development of the pathogen (Beldomenico y Begon, 2009). However, well-fed hosts that provide greater amounts of food have also been known to favor the development of the parasite and will help it produce more offspring (Tseng and Myers, 2014).

Table 3. Correlation between rust severity and the number of larvae (Mycodiplosis spp.) according to the strata of the plants and the sampling site in the municipal area of Xochitlán de Vicente Suárez, Puebla.

| Santa Lucia | Cuetzinapan | San Bernardo | |

|---|---|---|---|

| r*, p | r*, p | r*, p | |

| Bajo | 0.4016 | 0.3197 | 0.5054 |

| p=.000 | p=.000 | p=.000 | |

| Medio | 0.4194 | 0.3290 | 0.4943 |

| p=.000 | p=.000 | p=.000 | |

| Alto | 0.4198 | 0.4225 | 0.5287 |

| p=.000 | p=.000 | p=.000 | |

*Correlación de Spearman / * Spearman Correlation.

Figure 3. Relation between the number of Mycodiplosis spp. larvae and rust (H. vatatrix) severity in the high (A), middle (B) and low (C) strata of the coffee plants sampled in the municipal area of Xochitlán de Vicente Suárez, Puebla.

On the other hand, it is also known that the populations of prey and predators fluctuate due to their interaction, and this investigation found, in every case, a positive correlation between the severity of rust (prey) and the number of larvae (predators), which entails a mutual regulation between these populations. However, rust population varies for reasons different to the pressure of larva predation, making it difficult to determine whether the changes in the rust population are directly related to the changes in the population density of its predator (Mycodiplosis) or not. We can therefore infer that the population of the diptera has the potential to reduce the growth of the rust population (Davies, 2007).

The Coffee plant-Rust-Mycodiplosis interaction is evidently more complex than what has been described in the present work. Rust severity is possibly determined by the level of development and susceptibility of the crop, and given that the population of Mycodiplosis is dependent on the severity of rust (positive correlation), the population of this insect will increase if there is a greater availability of uredospores. A high rust severity has a direct effect on the coffee production potential of the next cycle, leading to a gradual decrease, which will begin with defoliations, followed by the progressive death of shoots and branches (CABI, 2018). Nevertheless, it is possible that the diptera, when eating the uredospores, helps maintain the balance in the levels of rust of the next cycle, stopping the production from decreasing noticeably.

Along with this, other biotic factors could make the interaction more complex, such as the presence of Lecanicillium lecanii, another biocontrolling agent, or the tree ant Azteca sericeasur (hymenoptera: formicidae), which may feed off the diptera, avoiding an efficient control of the rust (Hajian-Forooshani et al., 2016; Vandermeer et al., 2016). However, the distribution of A. sericeasur in Mexico is scarcely known (Vásquez-Bolaños, 2011) and has seemingly only been reported in the southeast of the country (Hajian-Forooshani et al., 2016; Vandermeer et al., 2016).

In several moments of the present investigation, larvae of the diptera were observed to mobilize inside the pustules, feeding off the uredospores, and were therefore found, not only in their digestive tract, but also on their integument. To date, whether this is enough for the insect to act as a disseminator of rust in the leaf itself and contribute to increase the severity in the plant, is unknown. There is an evident need to carry out further research on the life cycle of the larva to understand its function and relation with vastatrix in greater depth.

Conclusions

The distribution of rust (H. vastatrix) in the canopy of the three crop management scenarios was greater in the middle stratum of the plant, and the distribution of Mycodiplosis spp. is similar in the three strata of the plant. There is a positive correlation between the severity caused by rust in coffee plants (H. vastatrix) and the number of Mycodiplosis spp. larvae, which is favored without the use of fungicides.

Literatura Citada

Arroyo, EJ., Sánchez, F. and Barboza, LA. 2018. Infection model for analyzing biological control of coffee rust using bacterial anti-fungal compounds. Mathematical Biosciences 307:13-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mbs.2018.10.009. [ Links ]

Beldomenico, MP. and Begon, M. 2009. Disease spread, susceptibility and infection intensity: vicious circles? Trends in Ecology and Evolution 25(1): 21-27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2009.06.015 [ Links ]

Brinate, SVB., Martins, LD., Pereira, GNG., Cunha, VV., Sotero, A. de J., Amaral, JFT., Junior, WCJ. and Tomaz, MA. 2015. Copper can influence growth, disease control and production in arabica coffee trees. Australian Journal of Crop Science 9(7): 678-683. https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=357328620234232;res=IELHSS [ Links ]

CABI. 2018. Plantwise Knowledge Bank. Technical Factsheet: Coffee leaf rust Hemileia vastatrix. https://www.plantwise.org/KnowledgeBank/Datasheet.aspx?dsid=26865. [ Links ]

Coutinho, TA., Rijkenberg, FHJ. and Van ASCH, MAJ. 1994 The effect of leaf age on infection of Coffea genotypes by Hemileia vastatrix. Plant Patholgy 43(1):97-103. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3059.1994.tb00558.x [ Links ]

Davies, NB. 2007. Capítulo 14. Depredación. Pp. 299 -326. In: Smith, TM. y Smith, RL (eds.). Ecología. 6a edición. Pearson educación S.A, Madrid, España. 776 p. ISBN: 978-84-7829-084-0. [ Links ]

DGSV-SINAVEF-LANREF. 2016. Escalas de severidad de roya del café en hoja y planta. http://www.royacafe.lanref.org.mx/Documentos/EscalaSeveridadDefoliacionPlantayHoja.pdf [ Links ]

Haddad, F., Maffia, L., Mizubuti, E. and Texeira, H. 2009. Biological control of coffee rust by antagonistic bacteria under field conditions in Brazil. Biological Control 49(2): 114-119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2009.02.004 [ Links ]

Hajian-Forooshani, Z., Rivera, SIS., Jiménez, SE., Perfecto, I. and Vandermeer, J. 2016. Impact of regionally distinct agroecosystem communities on the potential for autonomous control of the coffee leaf rust. Journal of Environmental Entomology 45(6):1521-1526. https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvw125 [ Links ]

Henderson, PT. 2020. Elite-led development and Mexico’s independent coffee organisations in the wake of the rust epidemic, Third World Quarterly 41(6): 1012-1029, https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1729726 [ Links ]

Henk, DA., Farr, DF. and Aime, MC. 2011. Mycodiplosis (Diptera) infestation of rust fungi is frequent, wide spread and possibly host specific. Fungal ecology 4(4): 284-289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.funeco.2011.03.006. [ Links ]

Holz, B. 1970: Revision in Mitteleuropa vorkommender mycophager Gallmücken der Mycodiplosis-Gruppe (Diptera, Cecidomyiidae) unter Berücksichtigung ihrer Wirtsspezifität. Unpubl. Thesis. Stuttgart: University of Stuttgart, 237 p. [ Links ]

Jackson, D., Skillman, J. and Vandermeer, J. 2012. Indirect biological control of the coffee leaf rust, Hemileia vastatrix, by the entomogenous fungus Lecanicillium lecanii in a complex coffee agroecosystem. Biological Control 61(1): 89-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2012.01.004 [ Links ]

Jagadish, KS., Basavaraj, K. and Geetha, S. 2017. Spatial distribution of the mycophagous ladybird predator, Illeis cincta (Fabricius) (Coleoptera Coccinellidae) in relation to powdery mildew disease in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) Canopy. Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 5(5): 331-334. http://www.entomoljournal.com/archives/?year=2017&vol=5&issue=5&ArticleId=2341 [ Links ]

Kaushal, K., Mishra, AN., Varma, PK., Kapoor, KN. and Pandey, RN. 2001. Dipteran fly (Mycodiplosis sp): a natural bioagent for controlling leaf rust (Puccinia recondita var. tritici) of wheat (Triticum aestivum). Indian Journal of Agricultural Sciences 71(2): 136-138. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292558955_Dipteran_fly_Mycodiplosis_sp_A_natural_bioagent_for_controlling_leaf_rust_Puccinia_recondita_tritici_of_wheat_Triticum_aestivum [ Links ]

Kiel. 2014. Gall midges (Díptera: Cecidomyiidae: Cecidomyiinae) of Germany -Faunistics, ecology and zoogeography by Marcela Skuhravá, Václav Skuhravÿ and Hans Mayer. Faunistisch-Ökologische Arbeitsgemeinschaft e.V. 38: 1-200. https://www.zobodat.at/pdf/Faun-Oekol-Mitt_Supp_38_0001-0200.pdf [ Links ]

Kluth, S., Kruess, A. and Tscharntke, T. 2001. Interactions between the rust fungus Puccinia punctiformis and ectophagous and endophagous insects on creeping thistle. Journal of Applied Ecology 38(3): 548-556. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2664.2001.00612.x [ Links ]

Loland, J. and Singh, B. 2004. Copper contamination of soil and vegetation in coffee orchards after long-term use of Cu fungicides. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 69: 203-211. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:FRES.0000035175.74199.9a [ Links ]

Martínez, M., Cerna, R., Salinas, H. and Lizardo, A. 2013. Guía de manejo de plagas: lista verde y amarilla. CABI. https://www.plantwise.org/FullTextPDF/2018/20187800210.pdf [ Links ]

Merle, I., Pico, J., Granados, E., Boudrot, A., Tixier, P., de Melo, E., Filho, V., Cilas, C. and Avelino, J. 2019. Unraveling the complexity of coffee leaf rust behavior and development in different Coffea arabica agro-ecosystems. Phytopathology 110(2): 418-427. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-03-19-0094-R [ Links ]

Nelsen, DJ. 2013. A Phylogenetic Analysis of Species Diversity, Specificity, and Distribution of Mycodiplosis on Rust Fungi. Plant Pathology and Crop Physiology. LSU Master’s Theses. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2700 [ Links ]

Nutman, F. and Roberts, F. 1963. Studies on the Biology of Hemileia vastatrix Berk. & Br. Trans British Mycological Society 46: 27-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0007-1536(63)80005-4 [ Links ]

Rayner, R. 1961. Germination and Penetration studies on coffee rust (Hemileia vastatrix B. & Br.). Annals of Applied Biology 49(3): 497-505. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7348.1961.tb03641.x [ Links ]

SAGARPA-SENASICA. 2016. Roya del cafeto. Hemileia vastatrix (Barkeley & Broome) (Pucciniales: Chaconiaceae). Aviso público del riesgo y situación actual. 6 p. https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/172768/Aviso_p_blico_Roya_del_cafeto_2016.pdf [ Links ]

SAGARPA-SIAP. 2018. Atlas Agroalimentario 2012-2018. 50-51 pp. Primera edición. Ciudad de México. https://nube.siap.gob.mx/gobmx_publicaciones_siap/pag/2018/Atlas-Agroalimentario-2018. [ Links ]

SMN-CNA. Servicio Meteorológico Nacional- Comisión Nacional del Agua. 2018. https://smn.cna.gob.mx/es/climatologia/informacion-climatologica/informacion-estadistica-climatologica [ Links ]

Toniutti, L., Breitler, JC., Etienne, H., Campa, C., Doulbeau, S., Urban, L., Lambot, C., Pinilla, JCH. and Bertrand, B. 2017. Influence of environmental conditions and genetic background of arabica coffee (C. arabica L) on leaf rust (Hemileia vastatrix) pathogenesis. Frontiers in Plant Science 8: 2025. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.02025 [ Links ]

Tseng, M. and Myers, JH. 2014. The relationship between parasite fitness and host condition in an insect-virus System. PLoS ONE 9(9): e106401. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0106401 [ Links ]

Vandermeer, LK., Vandermeer, JH. and Perfecto, I. 2016. Disentangling endogenous versus exogenous pattern formation in spatial ecology: a case study of the ant Azteca sericeasur in southern Mexico. Royal Society Open Science 3: 160073. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.160073 [ Links ]

Vásquez-Bolaños, M. 2011. Lista de especies de hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) para México. Dugesiana 18(1): 95-133. https://www.antwiki.org/wiki/images/3/3f/V%C3%A1squezBola%C3%B1os2011Mexico.pdf [ Links ]

Vrijenhoek, R. 1994. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Molecular marine biology and biotechnology 3(5): 294-299. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/15316743_DNA_primers_for_amplification_of_mitochondrial_Cytochrome_C_oxidase_subunit_I_from_diverse_metazoan_invertebrates [ Links ]

Received: May 08, 2020; Accepted: August 06, 2020

text in

text in