Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista mexicana de fitopatología

On-line version ISSN 2007-8080Print version ISSN 0185-3309

Rev. mex. fitopatol vol.36 n.1 Texcoco Jan./Apr. 2018

https://doi.org/10.18781/r.mex.fit.1704-2

Review articles

Wood preservatives and microbial exudates with antagonistic activity against biological agents

1 Conservación y Manejo de Recursos Forestales, Facultad de Ingeniería en Tecnología de la Madera, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo., General. Francisco J. Mugica S/N, Ciudad Universitaria, C.P. 58030, Morelia, Michoacán, México.

2 Instituto de Investigaciones Químico Biológicas. Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo., General Francisco J. Mugica S/N, Ciudad Universitaria, C.P. 58030, Morelia, Michoacán, México.

Wood of low durability is susceptible of deterioration by xylophages and its protection is a technological goal not reached that generates economic and material losses. Alternatives to avoid the use of toxic preservative conventional and contaminating can be established by knowledge of the bacterial microecosystem in the wood. The protection of this material is possible to obtain it with bacteria and its exudates. The purpose of this research is to highlight that the biodeterioration of low durability wood is avoidable by means of microbiological strategies relevant for the control of xylophages’ fungi. The observation is that bacteria of the genera Arthrobacter, Bacillus and Pseudomonas and their exudates are potentially protective agents that exhibit different mechanisms of action such as antagonism, parasitism and the production of exudates containing molecules with effect: antimicrobial, chelator (siderophores) that inhibit enzymes or functions and volatile compounds (dimethylhexadecylamine). Knowledge of this microbial ecosystem will facilitate the construction of an alternative to the use of conventional wood preservatives and constitutes an area of opportunity. It is evident the absence of knowledge of antagonistic bacteria of the xylophages, the management of the production and composition of their exudates and their application, thus manifesting an unexplored field in the biotechnology of the preservation of wood.

Key words: xylophages’ fungi; lignin; wood; preservation; durability

La madera de baja durabilidad es susceptible de deterioro por xilófagos y su protección es una meta tecnológica no alcanzada que genera pérdidas económicas y materiales. Alternativas para evitar el uso de preservadores convencionales tóxicos y contaminantes se pueden establecer mediante el conocimiento del microecosistema bacteriano en la madera. La protección de este material es posible obtenerla con bacterias y sus exudados. El propósito de esta investigación es destacar que el biodeterioro de la madera de baja durabilidad es evitable mediante estrategias microbiológicas relevantes para el control de los hongos xilófagos. La observación es que bacterias de los géneros Arthrobacter, Bacillus y Pseudomonas y sus exudados potencialmente son agentes de protección que exhiben mecanismos de acción diferentes como, el antagonismo, el parasitismo y la producción de exudados que contienen moléculas con efecto: antimicrobiano (antibióticos), quelante (sideróforos) que inhiben enzimas o funciones y compuestos volátiles (dimetilhexadecilamina). El conocimiento de este ecosistema microbiano facilitará la construcción de una alternativa al uso de los preservadores convencionales de madera y constituye un área de oportunidad. Se evidencia la ausencia del conocimiento de bacterias antagónicas de los xilófagos, el manejo de la producción y composición de sus exudados y su aplicación, con lo que se manifiesta un campo inexplorado en la biotecnología de la preservación de la madera.

Palabras clave: xilófagos; lignocelulósico; madera; preservación; durabilidad

Introduction

Due to its organic composition, wood is vulnerable to biological degradation. In general, it is composed of cellulose in 40-61%, hemicellulose 15-30%, and lignin 17-35%, making it an excellent source of carbon to sustain the life cycles of some organisms. Wood in use is exposed to organisms such as bacteria, algae, fungi, and insects, which feed off their macromolecules, causing their degradation, and therefore, their physical and mechanical attributes, as well as their performance (Ibáñez, 2012). In the bacterial diversity there is a great number of genuses with species capable of deteriorating wood by degrading lignin and modifying their structure, such as Flavobacterium, Xanthomonas, Aeromonas, and Nocardia (Singh et al., 2016). Also, aerobic species of the genuses of Pseudomonas of Achromobacter also degrade structural polymers, which weaken the primary and secondary cell wall, with the alteration of the crystalline structure of these polymers and exposes them to promote the development of other deteriorator organisms (Zanni, 2004). Xylophagous algae are represented mainly by species of the genuses Clorophyta, Chrysophyta, and Cianophyta, which, when deteriorating wood, cause it to change color, as well as an increase in the absorption of solar radiation and water. However, the deterioration caused by bacteria and algae is less than the damage produced by fungi and hylophagous insects, the latter of which are the main causal agents of biodeterioration (Flower and Gonzalez-Meler, 2015).

In the construction and wood-based products industries, xylophagous fungi are accountable for great economic losses (Arbelo and Garbuyo, 2012). “Chromogenic” organisms are found in this group which, when penetrating the woody tissue via the hyphae, reach the cell cavities, an action that has the result of a change in color (Moglia et al., 2015). Meanwhile, the fungal species that cause “rotting” are grouped into different categories, such as the so-called white-rot, brown-rot and soft-rot. Fungi feed off the components of cell walls obtained by enzymes that degrade the structural prolymers, thus alter the physical and mechanical properties of the wood. The depolymerization of cell wall macromolecules is carried out with several hydrolytic enzymes that synthesize it rapidly, e.g. the degradation of crystalline is obtained with endo-1,4-ß-glucanases, exo-1,4-ß-glucanases, 1, 4-ß-glucosidases and other accessory enzymes (Schmidt, 2007).

Meanwhile, for a complex polymer without three-dimensional ordering such as lignin, composed of the concatenation of phenylpropanoic acids and alcohols, for its degradation and mineralization, the fungus uses an enzyme complex with activities of oxidases and peroxidases. The fungal metabolic pathway to the degradation of this polymer begins with the action of lignin peroxidase, which break carbon-carbon bonds or ether bonds within the complex molecule to produce monomers. Another interesting enzymatic complex is the one produced by some xylophagous basidiomycota that cause white rot. This complex includes lignin peroxidase, manganese peroxidase, a versatile molecule that uses hydrogen peroxide as an electron accepter, and laccase, which uses molecular oxygen. The latter enzyme is an oxidase made up of a co-factor with four copper atoms, the accepter of electrons is molecular oxygen. Also, laccase degrades non-phenolic substrates, more difficult to oxideze in the presence of co-oxidants; 1-hydroxybenzotriazole (1-HBT), 2,2′-azino-bis-( 3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) or violic acid (Subramanian et al., 2014).

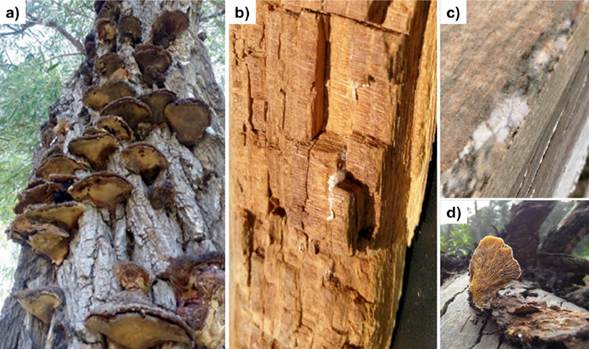

Some of the most important and harmful xylophagous organisms include basidiomycetes, which cause brown or cubid rot (e.g. Serpula lacrymans, Coniophora puteana, Antrodia vaillantii, Lentinus lepideus), capable of rapidly degrading cellulose, hemicellulose, and of structurally modifying lignin. In white rot, the basidiomycetes and some ascomycetes feed mostly of lignin, although they can decompose cellulose. Due to lignin degradation and the large amount of intact cellulose not used by these fungi, wood acquires a pale whit color. Some of the representative fungal species include Trametes versicolor, T. hirsuta and Schizophyllum commune. Meanwhile, ascomycetes that cause soft rot (Chaetomium globosum, Monodictys putredinis, Hypocrea muroiana, Cryphonectria parasitica and Fusarium oxysporum), the hyphae of which develop in the lumen and the inside of the secondary cell wall, mainly degrade cellulose, altering lignin structurally, causing a characteristic softening of the lignocellulosic material (Figure 1) (Patel et al., 2013).

Figure 1 Damage caused by xylophagous fungi in a standing Ganoderma applanatum tree (a), in the construction Antrodia vaillantii (b), sawn wood Ceratocystis sp. (c) and felled wood Pleurotus ostreatus (d).

On the other hand, insects are a relevant and diverse group in the animal kingdom, with over one million species described and an amount of up to 30 million species yet to be discovered (Stork et al., 2015). Likewise, they present a broad versatility to feed and survive. In terms of feeding habits, insects use, e.g. fresh plant tissue, organic animal matter in decomposition or dead plant matter. Such is the case of wood, and xylophagous insects carry this with the perforation and formation of galleries in search for cellulose and starch. This produces physical and mechanical damage and chromatic alterations in stored wood, process, service, and standing trees (Table 1) (Zanni, 2008). The insects that stand out in this group are coleoptera (beetles or woodworms) and lepidoptera (butterflies and moths), as well as isoptera (termites) and hymenoptera (wasps and ants). Isoptera and coleoptera are pointed out as producers of considerable damage to wooden structures and houses (NMX-C-222-1983; Blackwell and d´Errico 2000). Also, in large portions of North and Central America, bark insects of the genus Dendroctonus (D. frontalis, D. mexicanus) are the main pest in pine forests; they cause the loss of thousands of trees (FAO, 2007).

Table 1 Main xylophagous insects and the characteristics of the damages they cause on wood.

| Orden | Familia | Especie | Madera afectada | Ciclo biológico |

Autor |

| Isoptera | Termitidos | Reticulitermes lucifugus Rossi | Todas (celulosa), los insectos forman galerías separadas por finos tabiques. | Variable | Ulyshen, 2015 |

| Lepidoptera | Cossidos | Cossus cossus L. | Latifoliadas con humedad, producen grandes orificios separados por tabiques gruesos, generando galerías ovales y limpias. | 3 años | |

| Hymenoptera | Sirícidos | Sirex gigas L. Paururus Juencus L. | Trozas de resinas húmedas. Coníferas, forman galerías circulares llenas de aserrín. | 3 años | |

| Coleoptera | Bostríchidos | Apate capucina L. | Latifoliadas verdes, forman galerías limpias en forma de Y; Galerías larvarias llenas de aserrín. | 1 año | Berrocal, 2007; Agboton et al., 2017 |

| Líctidos | Lictus linearis Goez | Latifoliadas tropicales, se producen galerías de diámetro intermedio. | 1 año | ||

| Lictus brunneurs Steph. | En maderas tropicales se sabe que forman galerías circulares llenas de aserrín. | 1 año |

The protection of low-durability wood with chemical preservatives, however practical and cheap, is eco-toxic and requires immediate replacement with eco-friendly preservatives. Therefore, the purpose of this work is to establish the bases of protection for wood using microbiological strategies.

Classification of wood according to its resistance to xylophagous organisms

Wood can be categorized according to its use and durability (NMX-C-239-1985) and is subject to different levels of risk and to deterioration by xylophagous organisms. The different resistance present in this material is due to different structural and chemical factors contained in the woody tissue, typical variables of the species, age and development conditions at the time of cutting down. According to A.S.T.M D-2017-81, the classification of wood by its natural durability is shown in Table 2A. This feature is pondered in years, or in other words, how long it is capable of maintaining its mechanical properties after making contact with environmental factors. Later, the Board of the Cartagena Agreement (1988) categorized this material into five classes, according to the deterioration produced by xylophagous organisms (Table 2B). However, Bobadilla et al., (2005) catalogue its resistance according to the “Findlay Criterion”, by weight loss after the attack by fungi (Table 2C) (Findlay, 1951). The latter criterion highlights the importance of wood deterioration cause by xylophagous fungi, as well as the relevance of their control in which it is possible to use microbiological methods with this goal.

Table 2 Criteria and classification of wood based on its natural resistance and durability.

| A) Clasificación de la resistencia de la madera por su durabilidad natural (A.S.T.M D-2017-81) | ||

| Promedio de pérdida de peso (%) | Promedio de peso residual (%) | Clasificación y resistencia |

| 0-10 | 90-100 | Altamente resistente |

| 11-24 | 76-89 | Resistente |

| 25-44 | 56-75 | Moderadamente resistente |

| 45 o más | 55 o menos | Ligeramente resistente/no resistente |

| B) Clasificación de la durabilidad natural de las maderas en el caso de deterioro producido por hongos xilófagos | ||

| Años | Durabilidad | |

| Más de 20 | Muy durable | |

| 15- 20 | Durable | |

| 15-10 | Moderadamente durable | |

| 10-5 | Poco durable | |

| Menos de 5 | No durables | |

| C) Clasificación por resistencia de las maderas de acuerdo con la pérdida de peso | ||

| Pérdida de peso (%) | Categoría de resistencia | |

| Inferior a 5 | Muy resistente | |

| 5-10 | Resistente | |

| 10-20 | Moderadamente resistente | |

| 20-30 | No resistente | |

| Superior a 30 | Sin resistencia | |

Main chemical preservatives used on wood

The chemical wood preservation industry started in the 19th Century and has had great technological, social, historical and economic importance, since humans have tried to protect wood from physical and biological deterioration with different preserving agents. The mixtures of mineral salts with organic molecules have been extremely efficient; their classification depends on their nature and function (see Table 3). These salts control fungi and insects in wood in service and that is in touch with the ground. Its use was officialized by the American Wood Protection Association (AWPA) by norm P5-83, and some time later, it became official in Mexico (AWPA P5-83). Compounds such as Copper-chromium-arsenical (CCA) salts are extremely effective preservatives. Lignocellulosic materials treated with CCA exposed to extreme environment conditions can have a lifespan of decades. A verification carried out by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) showed that wooden stakes preserved with CCA restited the attack of diverse xylophagous organisms for over 60 years; the USDA foresees a lifespan of these materials five to ten times longer than without any preservations.

Table 3 Main substances used in the wood preservation industry.

| Criterio | Tipo | Sustancia | Autor |

| De acuerdo con el tipo de daño | Pudrición | 1-Cromo, Cobre y Arsénico (CCA)/CrO3 65.5, CuO 18.1, Ar2O5 16.4 | AWPA P5-83 |

| 2-Cobre, Azoles orgánicos (CA) | |||

| 3-Cobres, Azoles orgánicos y Boro (CAB) | |||

| 4-Cobre y Amonios Cuaternarios (ACQ) | |||

| 5- Boro | |||

| Mancha azul | 6-Quinolinolato de cobre/C18H12CuN2O2 | Lebow et al., 2015 | |

| 7-Tribromofenato de sodio/C6H3Br3 NaO | |||

| 8-Carbendazimas/ C9H9N3O2 | NMX-C-222-1983 | ||

| Retardantes de fuego | 9-Tetraborato de sodio/Na2B4O7. 10H2O 10-Ácido bórico/H3BO311-Sulfatos y fosfatos amónicos | ||

| Protectores contra luz ultravioleta y calor | 12-Pinturas con pigmentos metálicos | Veronovski et al., 2013; Auffan et al., 2014 | |

| De acuerdo con su naturaleza química | Oleosos | 13-Creosota | Singh y Singh, 2014; |

| Oleosolubles | 14-Pentaclorofenol (PCF)/C6HCl5O | Freeman et al., 2003 | |

| 15-Naftenatos | |||

| 16-Pentaclorofenato de sodio/C6Cl5NaO | |||

| 17-Oxido tributil estañoso/C24H54OSn2 | |||

| 18-Quinolinolato de cobre/ C18H12CuN2O2 | |||

| Hidrosolubles | 19-Sales múltiples | ||

| 20-Arsénico-cobre-amoniacales (ACA)/As250,20 %, Cu 49,80 % | |||

| 21-Cobre-cromo-arsenicales (CCA)/As2O5-5H2O 56 %, SO4Cu-2H2O 33 %, C2O7K2 11 % | |||

| 22-Cobre-cromo-boro (CCB)/CuO, Cr2O3, H3BO3 | |||

| 23-Compuestos de boro | |||

| Otras sales | 24-Cromo-Zinc-Cloro (CZC)/CrO3 20 %, Cl2Zn 80 % | ||

| 25-Flúor-Cromo-Arsénico-Fenol |

The indiscriminate release of these pesticides in uses of wood has contributed to the alarming deterioration of the ecosystem in order to increase the average lifespan of wood products at a minimum cost. This social and cultural practice is now an emerging and multi-factor environmental problem with a complex solution. However, in the 20th Century, some control measurements were set in motion for the release of pesticides in developed countries which were then copied and adapted in developing countries. One of them was the Food Quality Protection Act emitted by the U.S. government in 1966, and which included a proposal to drastically restrict the use of conventional pesticides. At the same time, the definition of pesticide proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO) was modified, and included biopesticides, such as dissuasive agents with a confounding effect, inhibitor of oviposition, anti-feeding and repellent, as well as biological control agents (Konradsen et al., 2003). With these measures adopted and adjusted for Mexican Legislation, a new academic, biotechnological and commercial opportunity opens up for the design of preservatives of microbiological origin for their use on low-durability wood. The control of the biodeterioration of lignocellulosic materials with preservatives based on the lifestyle and microbial strategies of ecological invasion is a non-toxic alternative.

Natural compounds with wood preserving potential

Nowadays, protection methods with natural components are the technological alternative to replace the conventional and harmful preservatives for low-durability wood. The use of this eco-friendly technology is slow and scarcely popular, due to the practicity and effectiveness at a low cost of conventional preservatives.

Among the alternative preservation methods, there are technological flaws that must be overcome, and that are the challenge to be faced, solved rapidly due to the alarming environmental deterioration and the change in attitude of the government. Some of these methods include the differences obtained under controlled conditions (laboratory) and the yield in the field, hardships in efficiency related to exposure, environmental conditions, and legislation conflicts worldwide (Singh and Singh, 2012). However, different natural compounds have justified their efficiency as wood preservatives. Historically, plant extracts were the molecular basis for the chemical synthesis of pyrethroids nicotinoids. Another successful example of insecticides are derived from the Azadirachta indica (neem) or Enterolobium cyclocarpum (guanacaste) trees, such as their essential oils or compounds contained in the heartwood, such as azadiracthin (Martinez et al., 2012; Raya-González et al., 2013). Likewise, microbial agents of biological control of known use and efficiency, and that compose a paradigm in the control of pests, such as Bacillus thuringensis, encourages to know the style and the life cycle of bacteria and other microorganism so as to use them in the preservation of wood. Likewise, new or novel synthetic molecules and natural products with biological activity such as pest controllers are surfacing, as a partial solution for the control of deleterious organisms that damage wood (Damian et al., 2010; González-Laredo et al., 2015; Ramírez-López et al., 2016).

The plant synthesizes secondary metabolites in the bark, fruit, leaf, wood, seed, or root. Its presence will become evident according to its surroundings, its circadian rhythm and life cycles, where its plant function is varied, including plant defense, and in this chemical arsenal of the plant, several bioactive compounds, inhibitors of the growth of pathogens, have been described. In this regard, extracts in Cinnamomun zeylanicum Ness. leaves contain components that are efficient to fight some xylophagous fungi and termites (Cheng et al., 2006; Tascioglu et al., 2013). Singh and Singh (2012) recently reported that leaf substances in Elaeocarpus dentatus display antifungal activities (brown rot), like Citrus x limon, Rosmarinus officinalis, Thymus vulgaris, Cinnamomum zeylanicum Ness. Syzygium aromaticum essential oils, are efficient to control growth in xylophagous fungi that produce mold; the most typical are species of the genuses Penicillium, Trichoderma, Fusarium and Aspergillus (Yang and Clausen, 2007; Matan and Matan, 2008) (Table 4). Other studies reported by Kartal et al., (2009) show a comparison of formulations based on cinnamaldehyde, cinnamic acid, cassia oils, and wood tar, which inhibited growth in Tyromyces palustris and Trametes versicolor, as well as providing resistance against the underground termite Coptotermes formosanus. Authors such as Stirling et al., (2007) pointed out that Cedrela odorata L. compounds present a biocidal action, due to tujaplicin, β-tujaplicinol, and plictic acid, toxic in Coniophora puteana, Postia placenta and Trametes versicolor, with metal chelating characteristics,. Plictic acid and ácido plicático and β-tujaplicinol simultaneously showed and interesting antioxdiant activity. Tascioglu et al. (2012) reported that both bark (Acacia mollissima) and heartwood (Schinopsis lorentzii) samples displayed antifungal activity due to the large content of condensed tannins. Likewise, flavonoids presented an activity of growth inhibition of the fungi Coniophora puteana, Irpex lacteus, Pleurotus ostreatus and T. versicolor (Carrillo-Parra et al., 2011; Nascimento et al., 2013). The plants present a varied profile of secondary metabolites, that suppress the growth of a wide variety of microorganisms. However, our interest is placed in the search for new plant components for the control of pathogens and their importance in the control of deteriorant microorganisms is discriminated. Therefore, the relevance of plant components in the protection of low-durability wood is a priority and calls for immediate attention.

Table 4 Main fungi responsible for white rot and brown rot in wood (Guillén et al., 2005; Schwarze, 2007; Singh y Singh, 2014).

| Especie fúngica |

Tipo de pudrición |

Madera afectada | Características del hongo | Infección |

| Xylaria hypoxylon | Blanca (esponjosa) | Latifoliadas, recientemente apeada o apilada. | Carpóforo anamorfo bifurcado y filamentoso, de himenio inserto en la superficie externa del ascoma (negro), ausente de pie, sabor u olor. | Se desarrolla sobre materia vegetal en descomposición, debido a la degradación de lignina produce podredumbre blanca. |

| Eutypa flavovirens | Blanca (fibroso veteado) | Latifoliadas tanto en pie como recién apeadas. | Tiene pseudostromas, peritecios con paredes oscuras, ascas cilíndricas, diatripáceos en forma alargada con ascosporas. | Ascomicetos que desarrollan fructificaciones sobre la madera, se ablanda, vetea, con cavidades; pierde peso: hifas de 0.5 a 5 μ, de q las menores, azuladas. Parte superior de los cuerpos fructíferos con pelos característicos. |

| Stereum hirsutum Willd | Blanca | Latifoliadas tanto en pie como recientemente apeadas. | Los cuerpos de fructificación son costrosos, en visera, ondulados, grises en la parte superior y amarillenta en la parte inferior. | Saprofita de madera muerta o viva, produciendo podredumbre blanca, basidiomicete responsable de la pudrición blanca de la madera, presenta fuerte actividad ligninolítica lacasa y manganeso peroxidasa. |

| Schizophyllum commune Fr. | Blanca | De coníferas y latifoliadas con alta humedad (Roble, Haya y Pino). | Cuerpos de fructificación encespelados, blancos de 3 cm y cubiertos de pelillos finos. Laminillas de los cuerpos de fructificación con borde partido a lo largo de toda su longitud. | Presenta actividad lacasa, manganeso peroxidasa y las lignino peroxidasa. Inespecífico de hospedero, se reporta creciendo sobre madera muerta o árboles en pie. Considerado una plaga causando daños a los árboles de plantaciones forestales, parques y jardines. |

| Polysticus versicolor Fr. | Blanca (fibrosa) | Latifoliadas y algunas coníferas. | La madera se decolora y las manchas se extienden: Hifas de 0,5 a 5 μ; cuerpo fructífero con tubos en la parte inferior Sensible a los taninos. Cuerpos de fructificación coloreados superiormente de forma concéntrica. | En considerado un hongo agresivo para la madera, degradándola rápidamente, parasitando árboles en pie. La infección se extiende de arriba y abajo del tronco desde el punto de inicio, recorriendo hacia fuera en las ramas e incluso en las raíces. En los árboles vivos el hongo produce esporóforos en gran abundancia, pero rara vez se produce fructificación en la madera. |

| Chaetomium globosum Kunze | Parda y blanca | De coníferas y latifoliadas con altos grados de humedad. | Hongo con fuerte presencia en suelo y plantas, se caracteriza por degradar la pulpa craft, Esta especie forma un micelio escaso y delgado, pero con numerosos ascocarpos verde oliva, que se distribuyen uniformemente sobre la superficie de la colonia. | Ataca a la madera que queda superficialmente blanda y al secar se resquebraja. Resiste a la anaerobiosis; los daños dependen de la densidad de la madera y la presencia de sales. Produce cavidades en la subcapa S2 de la pared celular. |

| Serpula lacrymans Wulf. | Parda seca (cúbica) | Coníferas y latifoliadas con distintos grados de humedad. | La madera se decolora, ablanda y agrieta: micelio externo de blanco pasa a rojo, coloreado quinoide; hifas de 2,5 a 4 μ. Micelio incoloro muy ramificado, hifas de 1,8 μ. Cuerpos de fructificación con basidiosporas que colorean de rojo-oro viejo. Cordones miceliares, los rizomorfos para transporte de agua, de 5,8 μ. | Organismo causante de severos daños a la madera, con la capacidad de generar pudrición en bajas condiciones de humedad. S. lacrymans es considerado como el destructor más perjudicial de materiales de construcción de madera en interiores en regiones templadas. |

| Lenzites abietina Bull. | Parda húmeda | Coníferas | Cuerpos de fructificación coloreados, hifas de 4 μ. Cistidios de gran tamaño. | Organismo con alta presencia en construcciones y todo tipo de objetos manufacturados con madera, degradan la celulosa y lignina en menor medida. En sitios en donde se almacena la madera, este hongo produce pérdida de peso en este material lignocelulósico. |

| Lentinus lepideus | Parda húmeda | Coníferas | Se distingue por presentar un sombrero convexo de 12 cm y pie de 7cm Cutícula de blanco a crema, escamosa. Láminas adnatas y decurrentes, espaciadas. Saprofito de troncos, tocones, muebles, madera vieja de ferrocarril y postes. | La madera se colorea, amarillenta, obscurece. Micelio blanco pasa a marrón purpura; hifas de 1-2,5 μ. Resistente a las creosotas, a altas temperaturas, a los medios anaeróbicos. Sin luz origina fructificación. |

Bacterial activity antagonistic to xylophagous fungi

Apart from components identified as having wood preservation capabilities from plants, such as essential oils, waxes, saps and extractives, there is a proposal to use microorganisms or their exudates as agents with antagonistic activity in the protection of wood against biological deterioration.

Out of the group of fungi that produce exudates, the species of the genus Trichoderma stand out, which suppress the growth of plant pathogens by microparasitism processes and/or the production of antifungal toxins (Widmer, 2014). Also, a wide group of bacteria are able to antagonize the development of some fungi using various action mechanisms. This group includes plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPRs), which, by producing siderophores (Saha et al., 2016), antibiotics (Tariq et al., 2017) or by competition for colonization spaces in roots and the production of organic compounds (COVs), generate an excellent and a distinctive antimicrobial effect (Table 5).

Table 5 Clasificación de las PGPRs depending on the antagonism with phytopathogens.

| PGPRs | Microrganismo antagónico |

Compuesto sintetizado |

Efecto inducido en plantas y fitopatógenos |

Autor |

| Directo | Bacillus pumilus y Bacillus licheniformis. | Giberelinas GA1, GA2, GA3 y GA4 | Elongación del tallo de aliso (Alnus glutinosa [L.] Gaertn.). | Gutiérrez- Mañero et al., 2001 |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens y Burkholderia cepacia | Ácido indol acético, sideróforos y ácido salicílico | Son eficientes en la promoción del crecimiento vegetal en cultivos de importancia económica. | Sivasakthi et al., 2014 | |

| Azotobacter, Pseudomona fluorecens, Mesorhizobium, Bacillus. | Hormonas vegetales, Ácido indol acético, amoniaco, cianuro de hidrogeno, sideroforos, solubilización de fosfatos | Promueve el crecimiento vegetal de la planta e inhibición de fitopatógenos como Aspergillus, Fusarium oxysporum, F. solani y Rhizoctonia botaticola. | Ahmad et al., 2008 | |

| Indirecto | Bacillus subtilis. | Iturina A | Inhibe el crecimiento de Fusarium sp., interactuando con las moléculas de colesterol, interrumpe la membrana citoplasmática fúngica, crea canales transmembranales, que permiten la liberación de iones vitales como el K+ | Ariza y Sánchez, 2012; Liu et al., 2015 |

| Bacillus sp. | Metabolitos secundarios con actividad anti fúngica | Inhibición de fitopatógenos como Curvularia sp. y Pyricularia grisea. Genera un efecto de biocontrol a través de la acción de las proteínas Cry1Ab y Cry1Ac. | Tejera et al., 2012 | |

| Bacillus sp. | Ácido indol acético, sideróforos, fitasa. Ácidos orgánicos, ACC desaminasa, cianógenos, enzimas líticas, oxalato oxidasa, fuentes de fosfatos orgánicos, potasio y zinc. | Promueve el crecimiento vegetal de la plata e inhibición de fitopatógenos como Macrophomina phaseolina, Fusarium oxysporum, F. solani, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, Rhizoctonia y Colletotricum sp., por medio de enzimas mucolíticas como quitinasa, β(1,3)-glucanasa y β(1,4)-glucanasa que degradan los componentes de la pared celular de hongos, la quitina, Β(1,3)-glucano y enlaces glucosídicos son lisados. | Kumar et al., 2012 |

COVs are organic molecules with a molecular mass of <300 Da and their main characteristic is a high vapor pressure that facilitates its volatilization (Zou et al., 2007). Some have anti-fungal potential and can act at a distance by diffusion in the air e.g. la rhizobacteria Arthrobacter agilis UMCV2, in an in vitro system, limited the growth of the fungi Botrytis cinerea and of the oomycete Phytophthora cinnamomi, due to the production of amine dimethylhexadecylamine (Velázquez-Becerra et al., 2013). Likewise, with this experimental approach, Orozco-Mosqueda et al., (2015) characterized the anti-fungal activity of diverse amines with antagonistic action on four strains of the xylophagous fungi Hypocrea sp. (UMTM3) and Fusarium sp. (UMTM13) obtained by fungal scrutiny in wood in decomposition, the origin of which was a pine-oak forest. The vitro test showed that the amines evaluated presented an inhibiting effect on the growth of the UMTM fungal isolations, in which dimethylhexadecylamine stood out. Due to its fungal deadliness, it is a potentially useful biomolecule in the preventive treatment of wood against the attack of xylophagous fungi and blue stain fungus. Included in the main bacterial genuses identified as producers of COVs is Pseudomonas, since Pseudomonas spp. synthesize hydrocyanic acid (HCN), a growth inhibitor in lignocellulosic pathogens. This metabolite is produced from glycine in essentially microaerophyllic conditions, where the HCN synthetases codified by the genes hcnABC are crucial for the competition of P. fluorescens (Haas and Défago, 2005). Other bacterial species of this genus that produce fungicides are P. chlororaphis (cyclohexanol), P. corrugata (2-ethyl-1-hexanol), P. aurantiaca (nonanal, benzothiazole and dimethyl sulfate). The compound 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol is produced by Lysobacter enzymogenes ISE13, used in the suprression of the life cycle of the fungus Colletotrichum acutatum and the oomycete Phytophthora capsici, since they inhibit mycelial growth, sporulation and the germination of spores and zoospores, as well as limiting the formation of the appressorium of C. acutatum (Pedraza, 2015). Also, an important number of strains of the genus Paenibacillus can act as antagonists to pathogenic fungi, such as P. ehimensis KWN38, which synthesizes butanol, which produces an inhibition (>50 %) in the development of hyphae of the fungi Rhizoctonia solani, Fusarium oxysporum and of the oomycete Phytophthora capsici (Naing et al., 2014). The bacteria Paenibacillus polymyxa presents volatile components such as 1-Octen-3-ol, benzothiazole, citronellol and 1,3-dichloropropene, which severely inhibit mycelial growth and affect the spreading of fungal pathogens, and they show an interesting insecticidal and herbicidal activity (Zhao et al., 2011). Likewise, the effect of Streptomyces platensis COVs on plant pathogenic fungi was reported in a study that identified antifungal compounds such as 2-phenylethanol and a derivative of felandren, substances responsible for the suppression of mycelial growth in Rhizoctonia solani, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Botrytis cinerea (Wan et al., 2008). Also strains of Bacillus subtilis produce COVs that significantly limit mycelial growth, pigment production (inhibition of 43 to 93 % respectively) and control the germination of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum with alkynes, alcohols, esters, ketones, amines, phenols and heterocyclic compounds (Liu et al., 2008). Microbial technologies based on sustainable principles that use agents with minimum environmental effects are the alternative and a perspective for the preservation of wood resources and its derivative.

Bacterial strategies for the control of fungi that deteriorate wood

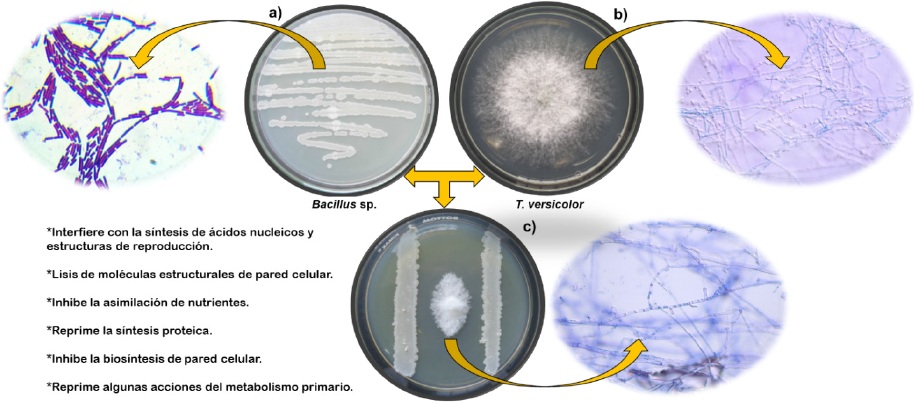

Bacteria present diverse mechanisms through which they can inhibit the growth og microorganisms that cause the deterioration of wood and other forestry products (Zavattieri et al., 2016; Cely et al., 2016). Some of the bioactive metabolites may supress fungal germination, spreading, or affect other activities of fungal development, such as invasive activity, the survival of fungal propagules embedded in clefts or the surface of wood to avoid their spreading (Figure 2). Most of these bacterial bioactives are catalogued in the group of antibiotics that inhibit the syntheses of the cell wall and of proteins, or alter the structure of the microbial membrane system, or cause the degradation of the genetic material of the target microorganism (Maksimov et al., 2011). Some species of the genus Bacillus produce insecticidal antibiotics and proteins e.g. B. subtilis produce antibiotics, yet considered PGPRs, since they promote plant growth and a biological control over some soil pathogens. B. thuringensis produces proteins that affect the development of insects, and is therefore used as an insecticide. Both bacilli are an unexplored source of bioactives for the control of wood-decaying fungi.

Figure 2 Trametes versicolor inhibition model for the secretion of Bacillus sp. metabolites (a) ths growth of the Bacillus sp bacterial isolation, (b) example of the development of the phytopathogenic fungus T. versicolor and (c) degree of inhibition of the bacterial metabolites on the growth of the phytopathogen when in simultaneous development under in vitro conditions after seven days.

Fungi require microelements for their development, and this need is vital, since these minerals can act as the farmaceutical target or objective and make them unavailable to the fungus and allow its control. The molecular chelating of ions avoids their availability and therefore the assimilation by the fungus, therefore its development. This fungal control strategy can be carried out with the siderophores, that are compounds with low molecular weight, produced and secreted by plant roots and some bacteria, e.g. siderophores capture elements such as iron (Fe+3) (Saha et al., 2016). The best siderophore-producing bacteria are found in the bacterial category of PGPRs. Although siderophores are interesting, for the purpose of this investigation, it is shown as a recurring topic for its use in the protection of wood. The bacterial ability to produce siderophores calls to attention for the chelating of iron, since when it forms a siderophore Fe3 + complex, and confining it in the bacterial cytosol with a specific receptor located in the bacterial membrane causes this micronurtient to become unavailable for microorganisms that lack the specific assimilation system and acknowledgement of such a complex (Radzki et al., 2013; Tariq et al., 2017). In this way, when using all or most of the soluble iron un the wood, fungal growth is suppressed, as well as in other microorganisms, as occurs in the rhizosphere (Bolívar-Anillo et al., 2016; Kumar et al., 2017). The ability of siderophores to act as suppressors of wood deteriorating fungi is unknown and its deleterious action may depend on chemical, physical and biological factors, as in the Rhizoshpere (Saha et al., 2016). However this is one of the challenges to overcome and that may be important in the preservation of this material. Another unexplored field in wood preservation and in the control of its biodeterioration are the lytic enzymes of polymers from fungal cell walls. These enzymes are produced by diverse microorganisms, including PGPRs, in which there have been descriptions of glucanases, proteases and chitinases. These act with the degradation of the polymers that make up the fungal cell wall of wood deteriorators, as described that takes place in pathogenic fungi (El-Tarabily and Sivasithamparam, 2006). Some of the main PGPRs that produce these enzymes are Bacillus altitudinis and B. amyloliquefaciens (Sunar et al., 2013; Tariq et al., 2017). As a natural renewable but definitely finite resource, wood is of great economic importance worldwide. A challenge in its preservation is to have strategies based on the microbial exudates to avoid the use of toxic substances in its control.

Conclusions

Bacterial metabolites such as dimethylhexadecylamine, 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol or of an antibiotic nature are potentially an alternative to conventional preservatives of low durability wood. But there is still a lack of knowledge in terms of production, use and doses of the microbial exudates. Therefore, the challenge is to attain high yields and reliability of these secondary metabolites comparable to the conventional preservatives using biotechnology strategies that include microbiological components.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the UMSNH for funding this investigation

REFERENCES

Agboton C, Onzo A, Korie S, Tamò M and Vidal S. 2017. Spatial and temporal infestation rates of Apate terebrans (Coleoptera: Bostrichidae) in cashew orchards in Benin, West Africa. African Entomology 25(1):24-36. https://doi.org/10.4001/003.025.0024 [ Links ]

Ahmad F, Ahmad I and Khan MS. 2008. Screening of free-living rhizospheric bacteria for their multiple plant growth promoting activities. Microbiological Research 163:173-181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2006.04.001 [ Links ]

Arbelo A y Garbuyo E. 2012. Patologías en la construcción en madera. Estudio de caso: vivienda Punta Colorada. Disponible en línea: https://www.colibri.udelar.edu.uy/bits-tream/123456789/1884/5/ARB6.pdf [ Links ]

Ariza Y y Sánchez L. 2012. Determinación de metabolitos secundarios a partir de Bacillus subtilis efecto biocontrolador sobre Fusarium sp. Nova 10:149-155. Disponible en línea: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1794-24702012000200002&lng=en&tlng=es [ Links ]

A.S.T.M D-2017-81. American Society for Testing and Materials. (ASTM). 1994. D-2017-81: Standard Method of Accelerated Laboratory Natural Decay Resistance for Woods. Annual Book of ASTM Standard, Philadelphia, v. 410, p. 324-328. Disponible en línea: https://www.astm.org/Standard/standards-and-publications.html [ Links ]

Auffan M, Masion A, Labille J, Diot MA, Liu W, Olivi L, Proux O, Ziarelli F, Chaurand P, Geantetf C, Bottero JY and Rose J. 2014. Long-term aging of a CeO2 based nano-composite used for wood protection. Environmental Pollution 188:1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2014.01.016 [ Links ]

AWPA P5-83 1983. American Wood-Preserver´s Association (AWPA). 1983. P5-83. Standard for waterborne preservatives. In: American Wood Preservers’ Association AWPA. Pp. 1-4 [ Links ]

Berrocal JA. 2007. Clasificación de daños producidos por agentes de biodeterioro en la madera. Revista Forestal Mesoamericana Kurú 4:54-62. Disponible en línea: http://revistas.tec.ac.cr/index.php/kuru/article/view/500/427 [ Links ]

Bobadilla EA, Pereyra O, Silva F y Stehr AM. 2005. Durabilidad natural de la madera de dos especies aptas para la industria de la construcción. Floresta 35:419-428. http://dx.doi.org/10.5380/rf.v35i3.5192 [ Links ]

Bolívar-Anillo HJ, Contreras-Zentella ML y Teherán-Sierra LG. 2016. Burkholderia tropica una bacteria con gran potencial para su uso en la agricultura. TIP 19:102-108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.recqb.2016.06.003 [ Links ]

Carrillo-Parra A, Hapla F, Mai C y Garza-Ocañas F. 2011. Durabilidad de la madera de Prosopis laevigata y efecto de sus extractos en hongos que degradan la madera. Madera y bosques 17:7-21. Disponible en línea: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S140504712011000100001&lng=es&tlng=en [ Links ]

Cely MV, Siviero MA, Emiliano J, Spago FR, Freitas VF, Barazetti AR, Goya ET, de Souza Lamberti, G, dos Santos IM, De Oliveira AG and Andrade G. 2016. Inoculation of Schizolobium parahyba with Mycorrhizal Fungi and Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria Increases Wood Yield under Field Conditions. Frontiers in Plant Science 7:1-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.01708 [ Links ]

Cheng SS, Liu JY, Hsui YR and Chang ST. 2006. Chemical polymorphism and antifungal activity of essential oils from leaves of different provenances of indigenous cinnamon (Cinnamomum osmophloeum). Bioresource Technology 97:306-312. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2005.02.030 [ Links ]

Damian BLM, Martinez MRE, Salgado GR y Martinez PMM. 2010. In vitro antioomycete activity of Artemisia ludoviciana extracts against Phytophthora. Boletín Latinoamericano y del Caribe de Plantas Medicinales y Aromáticas 9:136-142. ISSN:0717-7917. Disponible en linea: http://www.redalyc.org/html/856/85612475009/ [ Links ]

El-Tarabily KA and Sivasithamparam K. 2006. Non-strep-tomycete actinomycetes as biocontrol agents of soil-borne fungal plant pathogens and as plant growth promoters. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 38:1505-1520. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2005.12.017 [ Links ]

FAO 2007. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. State of the world’s forests. Rome, Italy: FAO Forestry Department. [ Links ]

Findlay WPK. 1951. The value of laboratory test on wood preservatives. [S.l.]: Convention British Wood Preserving Association. [ Links ]

Flower CE and Gonzalez-Meler MA. 2015. Responses of temperate forest productivity to insect and pathogen disturbances. Annual Review of Plant Biology 66:547-569. Disponible en línea: http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/pdf/10.1146/annurev-arplant-043014-115540 [ Links ]

Freeman MH, Shupe TF, Vlosky RP and Barnes HM. 2003. Past, present, and future of the wood preservation industry: wood is a renewable natural resource that typically is preservative treated to ensure structural integrity in many exterior applications. Forest Products Journal 53(10):8-16. Disponible en línea: http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA110822270&sid=googleScholar&v=2.1&it=r&linkaccess=fulltext&issn=00157473&p=AONE&sw=w&authCount=1&u=umsnh1&selfRedirect=true [ Links ]

González-Laredo RF, Rosales-Castro M, Rocha-Guzmán NE, Gallegos-Infante JA, Moreno-Jiménez MR y Karchesy JJ. 2015. Wood preservation using natural products. Madera y Bosques 21:63-76. http://dx.doi.org/10.21829/myb.2015.210427 [ Links ]

Guillén F, Martínez MJ, Gutiérrez A and Del Rio JC. 2005. Biodegradation of lignocellulosics: microbial, chemical, and enzymatic aspects of the fungal attack of lignin. International Microbiology 8:195-204. Disponible en línea: http://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/im/v8n3/07%20Martinez.pdf [ Links ]

Gutiérrez-Mañero FJ, Ramos-Solano B, Probanza A, Mehouachi J, Tadeo F and Talon M. 2001. The plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria Bacillus pumilus and Bacillus licheniformis produce high amounts of physiologically active gibberellins. Physiologia Plantarum 111:206-211. http://dx.doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-3054.2001.1110211.x [ Links ]

Haas D and Défago G. 2005. Biological control of soil-borne pathogens by fluorescent pseudomonads. Nature Reviews Microbiology 3:307-319. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrmi-cro1129 [ Links ]

Ibáñez OC, Mantero C, Rabinovich M, Cecchetto G y Cerdeiras P. 2012. Deterioro y preservación de madera. Revista Digital Universitaria 13(5):1-15 Disponible en línea: http://www.revista.unam.mx/vol.13/num5/art55/index.html [ Links ]

Kartal SN, Yoshimura T and Imamura Y. 2009. Modification of wood with Si compounds to limit boron leaching from treated wood and to increase termite and decay resistance. International Biodeterioration and Biodegradation 63:187-190. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2008.08.006 [ Links ]

Konradsen F, van der Hoek W, Cole DC, Hutchinson G, Daisley H, Singh S and Eddleston M. 2003. Reducing acute poisoning in developing countries-options for restricting the availability of pesticides. Toxicology 192(2):249-261. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0300-483X(03)00339-1 [ Links ]

Kumar H, Dubey RC and Maheshwari DK. 2017. Seed-coating fenugreek with Burkholderia rhizobacteria enhances yield in field trials and can combat Fusarium wilt. Rhizosphere 3:92-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rhisph.2017.01.004 [ Links ]

Kumar P, Dubey RC and Maheshwari DK. 2012. Bacillus strains isolated from rhizosphere showed plant growth promoting and antagonistic activity against phytopathogens. Microbiological Research 167:493-499. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2012.05.002 [ Links ]

Lebow S, Arango R, Woodward B, Lebow P and Ohno K. 2015. Efficacy of alternatives to zinc naphthenate for dip treatment of wood packaging materials. International Biodeterioration and Biodegradation 104:371-376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2015.07.006 [ Links ]

Liu C, Sheng J, Chen L, Zheng Y, Lee DYW, Yang Y, Xu M and Shen L. 2015. Biocontrol activity of Bacillus subtilis isolated from Agaricus bisporus mushroom compost against pathogenic fungi. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 63(26):6009-6018. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.5b02218 [ Links ]

Liu W, Mu W, Zhu B and Liu F. 2008. Antifungal activities and components of VOCs produced by Bacillus subtilis G8. Current Research on Bacteriology 1:28-34. Disponible en línea: http://www.docsdrive.com/pdfs/ansinet/crb/2008/28-34.pdf [ Links ]

Maksimov IV, Abizgil’Dina RR and Pusenkova LI. 2011. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria as alternative to chemical crop protectors from pathogens (review). Applied Biochemistry and Microbiology 47:333-345. http://dx.doi.org/10.1134/S0003683811040090 [ Links ]

Manual del grupo andino para la preservación de maderas. 1988. Ed. Proyecto subregional de promoción industrial de la madera para construcción de la Junta del Acuerdo de Cartagena L. [ Links ]

Martinez PMM, del Rio RE, Flores GA, Martínez MRE, Ron Echeverria OA and Raya GD. 2012. Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb: The biotechnological profile of a tropical tree. Boletín Latinoamericano y del Caribe de Plantas Medicinales y Aromáticas 11:385-399. Disponible en línea: http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/856/85624131001.pdf [ Links ]

Matan N and Matan N. 2008. Antifungal activities of anise oil, lime oil, and tangerine oil against molds on rubberwood (Hevea brasiliensis). International Biodeterioration and Biodegradation 62:75-78. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j. ibiod.2007.07.014 [ Links ]

Moglia JG, Amórtegui IC y Giménez AM. 2015. Ocurrencia de la mancha roja en el leño de Aspidosperma quebracho-blanco. Revista de Ciencias Forestales 23:1-2. Disponible en línea: http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/481/48145593003.pdf [ Links ]

Naing KW, Anees M, Kim SJ, Nam Y, Kim YC and Kim KY. 2014. Characterization of antifungal activity of Paenibacillus ehimensis KWN38 against soilborne phytopathogenic fungi belonging to various taxonomic groups. Annals of Microbiolog 64:55-63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13213-013-06. [ Links ]

Nascimento MS, Santana ALBD, Maranhão CA, Oliveira LS and Bieber L. 2013. Phenolic extractives and natural resistance of wood. Pp:349-370. In Biodegradation-Life of Science. http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/56358 [ Links ]

NMX-C-222-1983. Norma Mexicana. “Industria de la Construcción-Vivienda de Madera Prevención de Ataque por Termitas-Especificaciones”. [ Links ]

NMX-C-239-1985. Norma Mexicana para la “Calificación y clasificación de la madera de pino para uso estructural”. [ Links ]

Orozco-Mosqueda M, Valencia-Cantero E, López-Albarrán P, Martínez-Pacheco M y Velázquez-Becerra C. 2015. La bacteria Arthrobacter agilis UMCV2 y diversas aminas inhiben el crecimiento in vitro de hongos destructores de madera. Revista Argentina de Microbiología 47:219-228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ram.2015.06.005 [ Links ]

Patel N, Oudemans PV, Hillman BI and Kobayashi DY. 2013. Use of the tetrazolium salt MTT to measure cell viability effects of the bacterial antagonist Lysobacter enzymogenes on the filamentous fungus Cryphonectria parasitica. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 103(6):1271-1280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10482-013-9907-3 [ Links ]

Pedraza RO. 2015. Siderophores production by Azospirillum: biological importance, assessing methods and biocontrol activity. In Handbook for Azospirillum. Pp. 251-262. Springer International Publishing. 514p. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-06542-7_14 [ Links ]

Radzki W, Mañero FG, Algar E, García JL, García-Villaraco A and Solano BR. 2013. Bacterial siderophores efficiently provide iron to iron-starved tomato plants in hydroponics culture. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 104(3):321-330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10482-013-9954-9 [ Links ]

Ramírez-López CB, García-Sánchez E, Martínez-Muñoz RE, Del Río RE y Martínez-Pacheco MM. 2016. Chemical composition of the essential oil from Ageratina jocotepecana and its repellent effect on drywood termite Incisitermes marginipennis. Boletín Latinoamericano y del Caribe de Plantas Medicinales y Aromáticas. 15(1):53-60. Disponible en línea: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=85643330005 [ Links ]

Raya-González D, Martínez-Muñoz RE, Ron-Echeverría OA, Flores-García A, Macías-Rodríguez LI and Martínez-Pacheco MM. 2013. Dissuasive effect of an extract aqueous from Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq) Griseb on the drywood termite Incisitermes marginipennis (Isoptera:Kalotermitidae) (Latreille). EJFA 25:524-530. http://dx.doi.org/10.9755/ejfa.v25i7.15987 [ Links ]

Saha M, Sarkar S, Sarkar B, Sharma B K, Bhattacharjee S and Tribedi P. 2016. Microbial siderophores and their potential applications: a review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 23(5):3984-3999. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-015-4294-0 [ Links ]

Schmidt O. 2007. Indoor wood-decay basidiomycetes: damage, causal fungi, physiology, identification and characterization, prevention and control. Mycological Progress 6:261-279. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11557-007-0534-0 [ Links ]

Schwarze FWMR. 2007. Wood decay under the microscope. Fungal Biology Reviews 21(4):133-170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbr.2007.09.001 [ Links ]

Singh AP and Singh T. 2014. Biotechnological applications of wood-rotting fungi: A review. Biomass and Bioenergy 62:198-206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biom-bioe.2013.12.013 [ Links ]

Singh AP, Kim YS and Singh T. 2016. Bacterial degradation of wood. Secondary Xylem Biology: Origins, Functions, and Applications 9:169-190. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-802185-9.00009-7 [ Links ]

Singh T and Singh AP. 2012. A review on natural products as wood protectant. Wood Science and Technology 46:851-870. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00226-011-0448-5 [ Links ]

Sivasakthi S, Usharani G and Saranraj P. 2014. Biocontrol potentiality of plant growth promoting bacteria (PGPR)-Pseudomonas fluorescens and Bacillus subtilis: A review. African Journal of Agricultural Research 9(16):1265-1277. https://dx.doi.org/10.5897/AJAR2013.7914 [ Links ]

Stirling R, Daniels CR, Clark JE and Morris PI. 2007. Methods for determining the role of extractives in the natural durability of western red cedar. International Research Group on Wood Protection. Doc No. IRG-WP 07e20356. [ Links ]

Stork NE, McBroom J, Gely C and Hamilton AJ. 2015. New approaches narrow global species estimates for beetles, insects, and terrestrial arthropods. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112(24):7519-7523. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1502408112 [ Links ]

Subramanian J, Ramesh T and Kalaiselvam M. 2014. Fungal laccases-properties and applications: a review. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biological Archive 5(2):8-16. Disponible en línea: http://www.ijpba.info/ijp-ba/index.php/ijpba/article/viewFile/1237/881 [ Links ]

Sunar K, Dey P, Chakraborty U and Chakraborty B. 2013. Biocontrol efficacy and plant growth promoting activity of Bacillus altitudinis isolated from Darjeeling hills, India. Journal of Basic Microbiology 55:91-104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jobm.201300227 [ Links ]

Tariq M, Noman M, Ahmed T, Hameed A, Manzoor N and Zafar M. 2017. Antagonistic features displayed by Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR): A Review. Journal of Plant Science and Phytopathology 1:38-43. Disponible en línea: https://www.heighpubs.org/jpsp/pdf/jpsp-aid1004.pdf [ Links ]

Tascioglu C, Yalcin M, de Troya T y Sivrikaya H. 2012. Termiticidal properties of some wood and bark extracts used as wood preservatives. BioResources 7:2960-2969. Disponible en línea: http://ojs.cnr.ncsu.edu/index.php/BioRes/article/view/BioRes_07_3_2960_Tascioglu_YTS_Termiticidal_Wood_Bark_Extracts [ Links ]

Tascioglu C, Yalcin M, Sen S and Akcay C. 2013. Antifungal properties of some plant extracts used as wood preservatives. International Biodeterioration and Biodegradation 85:23-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2013.06.004 [ Links ]

Tejera B, Heydrich M y Rojas MM. 2012. Antagonismo de Bacillus spp. frente a hongos fitopatógenos del cultivo del arroz (Oryza sativa L.). Revista de Protección Vegetal 27:117-122. Disponible en línea: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1010-27522012000200008 [ Links ]

Ulyshen MD. 2015. Insect-mediated nitrogen dynamics in decomposing wood. Ecological Entomology 40:97-112. https://doi.org/10.1111/een.12176 [ Links ]

Velázquez-Becerra C, Macías-Rodríguez LI, López-Bucio J, Flores-Cortez I, Santoyo G, Hernández-Soberano C and Valencia-Cantero E. 2013. The rhizobacterium Arthrobacter agilis produces dimethylhexadecylamine, a compound that inhibits growth of phytopathogenic fungi in vitro. Protoplasma 25:1251-1262. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00709-013-0506-y [ Links ]

Veronovski N, Verhovšek D and Godnjavec J. 2013. The influence of surface-treated nano-TiO2 (rutile) incorporation in water-based acrylic coatings on wood protection. Wood science and technology 47(2):317-328. http://dx.doi. org/10.1007/s00226-012-0498-3 [ Links ]

Wan M, Li G, Zhang J, Jiang D and Huang HC. 2008. Effect of volatile substances of Streptomycesplatensis F-1 on control of plant fungal diseases. Biological Control 46:552-559. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2008.05.015 [ Links ]

Widmer TL. 2014. Screening Trichoderma species for biological control activity against Phytophthora ramorum in soil. Biological Control 79:43-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bio-control.2014.08.003 [ Links ]

Yang VW and Clausen CA. 2007. Antifungal effect of essential oils on southern yellow pine. International Biodeterioration and Biodegradation 59:302-306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2006.09.004 [ Links ]

Zanni E. 2004. Patología de madera. Degradación y Rehabilitación de Estructuras de Madera. Primera Edición. Editorial Brujas. Córdoba, Argentina. 244p. [ Links ]

Zanni E. 2008. Patología de la construcción y restauro de obras de arquitectura. Primera Edición. Editorial Brujas. Córdoba, Argentina. 300p. [ Links ]

Zavattieri MA, Ragonezi C and Klimaszewska K. 2016. Adventitious rooting of conifers: influence of biological factors. Trees 30(4):1021-1032. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-016-1412-7 [ Links ]

Zhao LJ, Yang XN, Li XY, Wei MU and Feng LIU. 2011. Antifungal, insecticidal and herbicidal properties of volatile components from Paenibacillus polymyxa strain BMP-11. Agricultural Sciences in China 10:728-736. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1671-2927(11)60056-4 [ Links ]

Zou CS, Mo MH, Gu YQ, Zhou JP and Zhang KQ. 2007. Possible contributions of volatile-producing bacteria to soil fungistasis. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 39:2371-2379. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2007.04.009 [ Links ]

Received: April 20, 2017; Accepted: September 30, 2017

text in

text in