Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista mexicana de fitopatología

On-line version ISSN 2007-8080Print version ISSN 0185-3309

Rev. mex. fitopatol vol.33 n.2 Texcoco 2015

Phytopatological notes

Socioeconomic and parasitological factors that limits cocoa production in Chiapas, Mexico

1INIFAP Campo Experimental Rosario Izapa, Km. 18 Carretera Tapachula-Cacahoatan, Tuxtla Chico, Chiapas, México: 30870.

2Colegio de Postgraduados-Campus Montecillo. Instituto de Fitosanidad. km 36.5 Carretera México-Texcoco, Montecillo, Texcoco, México: 56230.

3INIFAP Campo Experimental Rosario Izapa, Km. 18 Carretera Tapachula-Cacahoatan, Tuxtla Chico, Chiapas, México: 30870

4INIFAP Campo Experimental Centro de Chiapas, Km. 3 Carretera Ocozocoautla-Cintalapa, Ocozocoautla de Espinoza, Chiapas, México: 29140.

The main goal of this research was to identify the socioeconomic and parasitological factors that limit cocoa production in Chiapas, Mexico. One hundred and nine cacao-growers were visited and interviewed in the two main cocoa-producing regions. According to results only 14.7 % farmers grow white-almond cacao. The average production unit is 2.6 hectares. Cacao growers are 59 years-old on average and 56 % of them did not finish elementary school. Only 19.3 % of the production units are under woman responsibility. Average yield is 118 kg ha-1 and 60.5 % growers sell cacao to intermediaries. Pests that affect the crop and their occurrence include Moniliophthora roreri (100 %), Phytophthora capsici (67%), Fusarium sp. (10.1 %), Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (3.7 %), Ceratocystis cacaofunesta (0.9 %), Atta sp. (33.9 %), Toxoptera aurantii (11 %), squirrels (7.3 %), Xyleborus ferrugineus, Xylosandrus morigerus, Hypothenemus birmanus, Corthylus minutissimus, Taurodermus sharpi, Hypothenemus interstitialis (5.5 %), Vanduzea segmentata (5.5 %), woodpecker (4.6 %), Selenothrips rubrocintus (3.7 %), Clastoptera laenata (3.7 %) and mole (3.7 %). Moniliophthora is the main factor that affects cacao survival and biodiversity in Chiapas. The disease destroys production, makes control uneconomical and causes growers to abandon their plantations.

Key words: Mexico; cacao; decline; socioeconomic; pests

El objetivo de la investigación fue identificar los factores socioeconómicos y parasitológicos que limitan la producción del cacao en Chiapas, México. Se llevaron a cabo encuestas y visitas a 109 productores de las dos principales regiones productoras. Entre los resultados más importantes se registró que solamente el 14.7 % de los productores cultiva cacao de almendra blanca. La unidad de producción promedio es de 2.6 ha. Los productores tienen una edad promedio de 59 años y el 56 % de ellos no completó su instrucción primaria. Sólo el 19.3 % de las unidades productivas está bajo la responsabilidad de mujeres. El rendimiento promedio es de 118 kg ha-1 y el 60.5 % de los productores vende el cacao a intermediarios. Las plagas que afectan al cultivo y su frecuencia son: Moniliophthora roreri (100 %), Phytophthora capsici (67 %), Fusarium sp. (10.1 %), Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (3.7 %), Ceratocystis cacaofunesta (0.9 %), Atta sp. (33.9 %), Toxoptera aurantii (11 %), ardillas (7.3 %), Xyleborus ferrugineus, Xylosandrus morigerus, Hypothenemus birmanus, Corthylus minutissimus, Taurodermus sharpi, Hypothenemus interstitialis (5.5 %), Vanduzea segmentata (5.5 %), pájaro carpintero (4.6 %), Selenothrips rubrocintus (3.7 %), Clastoptera laenata (3.7 %) y tuzas (3.7 %). Moniliophthora es el principal factor que afecta la supervivencia del cacao y su biodiversidad en Chiapas. Esta enfermedad destruye la producción, hace su control no rentable e induce a los agricultores a abandonar sus huertas.

Palabras clave: México; Cacao; Decadencia; Socioecioeconómicos; Plagas

Introduction

Cacao (Theobroma cacao L), originally from South America, is a crop of economic, industrial, social, cultural and environmental importance (Motamayor et al. 2002). In Mexico, a decreasing trend in cacao production has been observed in the past decade. Production in 2003 was 49,964 tons, while production in 2013 was only 27,844 tons, and with the growing area decrease by 20,668 hectares (ha). Chiapas is one of the most important cocoa-growing states, ranked second in production following Tabasco, whose area sown to cacao is 20,299 ha, and harvests 9,080 ton at a rate of 440 kg ha-1 (SIAP, 2014). The major cacao growing areas of Chiapas are Soconusco and northern Chiapas (SIAP, 2014), where cacao has been part of the state's culture, economy, society and history (Nájera, 2012).

A recent effort led by Avendaño et al. (2013) has shown the economic, social, cultural and environmental value of cacao plantations. The effort known as "Participative improvement" (Aguirre, 2009; Avendaño et al., 2013; Díaz et al., 2013) recognizes cacao as a source of diversity and selects the best plants in terms of disease resistance and outstanding organoleptic properties and outstanding marketing potential.

Unfortunately, cacao production faces a crisis sparked by environmental, technological, economic and social factors, which is worsened by phytosanitary problems, including diseases that destroy entire plantations and force growers to leave behind this ancestral crop (González, 2005). In Mexico, no socioeconomic and parasitological factors that specifically limit production have been identified, and everything indicates that diseases are contributing significantly to the disappearance of this important crop. Thus the objective of this study was to identify the socioeconomic and parasitological factors that limit cacao production in Chiapas, Mexico.

Materials and Methods

Study area. In 2013 a series of surveys was undertaken which included visits to 109 cacao growers from 45 locations in eight municipalities from the two major cacao growing-regions in Chiapas: Soconusco and northern Chiapas. In the Soconusco region 32 surveys were conducted in the municipalities of Cacahoatán, Huehuetán, Tapachula, Tuxtla Chico and Tuzantán. In the northern region 13 surveys were conducted in the municipalities of Ostuacán, Pichucalco and Ixtacomitán.

Sample size. For the selection of participant growers and growers visited, a random selection method without replacement was used based on SAGARPAS' 2013 cacao growers census. In cacao plots a five diamond pattern was used to estimate the presence of pests.

Survey and occurrence calculations. The survey was designed according to Ghiglione and Matalón (1989), Córdova et al. (2001), Díaz, et al. (2013) and Quispe (2013) reports, and included eight sections with 62 questions: 1. Identification card (producer's name, community and date); 2. General information (age, gender, education, landholding and economic activities, funding, training, organization, labor); 3. Plot information (area, type of cacao, planting distance, shade trees); 4. Agronomic management (weed control, fertilization, drainage); 5. Pests (observed pests, importance, control); 6. Diseases (observed diseases, importance, control); 7. Production and marketing of the cocoa processing, price, (production and marketing); and 8. Expectations (continue planting cacao). Responses from farmers interviewed were collected and occurrences defined using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Version 20).

Identification of parasitological problems. During visits to the selected plots, insects and samples of plants showing disease symptoms were collected for identification and diagnosis purposes, respectively. Insects were kept in alcohol at 70 %. Then, they were mounted on entomological pins and identified at species level using taxonomic keys. A second opinion from an insect taxonomy expert was requested for each insect. For diseases, samples of plants showing symptoms were placed in a moisture chamber for 48 hours. If after this period, structures of the causing agent were present, they were identified according to their taxonomic group. Otherwise, cuts were made to the diseased tissue, which was disinfected with sodium hypochlorite (1.5 %) for three minutes, washed three times in autoclaved distilled water, dried, and finally planted in a PDA growth medium. The resulting isolations were purified using the hyphal tip technique and incubated under 12 hours of white light until sporulation. In all cases, nucleic acids were extracted (Qiagen, USA) for molecular identification of organisms (BLAST NCBI); this was achieved by amplifying the ITS region with primers ITS4 e ITS5 and the protocol of White et al. (1990).

Results and Discussion

Economic aspects. In Chiapas, cacao production is a smallholder activity. 58.7 % smallholders own plots of less than two hectares and 41.3 % hold larger plots. The average age of growers is 59 years old. 80.7 % cacao growers are male and only 19.3 % are female. Women are also responsible for household chores and childcare, thus tripling their workload, according to Suárez et al. (2011). Women are engaged in activities such as harvest, washing, fermentation and drying, but women's contribution is not considered significant to the production process, belittling their important participation in the cacao production process. This male behavior has also been observed in other crops (Maier, 1998; Agarwal, 1992; Cortez and Pizarro, 2001).

Education. More than 50 % cacao growers did not finish elementary education, and only 4.6 % hold a B.S. degree (Table 1). Engler and Toledo (2010) suggested that the low level of education affects negatively the adoption rates of technology innovations. This study found that only 53.2 % cacao growers had requested and received technical training.

Table 1 Level of education of cacao growers (Theobroma cacao L.) in the Soconusco and northern Chiapas regions.

Legal status of plots. 67 % of the production units are ejidos and the remainder are private property. In Mexico, the ejido is the most important form of collective land ownership, which is ruled by an internal regulation that sets forth the terms for its economic and social organization (Legislación Agraria, 2004). This means that plots for cacao production are subject to limited marketing; for example, 66.1 % of the production units were inherited and only 34 % were purchased.

Cacao growers have started to diversify their economic activities to fulfill their income needs. For example, 16.5 % of them are traders, service suppliers and grow other crops. 68.8 % cultivate cacao with their own resources, and 31.2 % of them have received some financial support.

Organization. 60.6 % cacao growers belong to an association that facilitates their access to the financial and training resources offered by the government. The main cacao growers associations in the state of Chiapas are Asociación Agrícola Local de Productores de Cacao de Tapachula (Tapachula Local Agricultural Association of Cacao Growers); Asociación Agrícola Local de Productores de Cacao de Tuxtla Chico (Tuxtla Chico Local Agricultural Association of Cacao Growers); Sociedad de Producción Rural Cuevas de Tigre de Pichucalco (Pichucalco Tiger Caves Rural Production Society); Asociación Agrícola Local de Productores de Cacao de Tuzantán (Tuzantán Local Agricultural Association of Cacao Growers); and Alianza del Cacao de Tuxtla Chico (Tuxtla Chico Cococa Cooperative Alliance). From these, 51.1 % are municipal and 43.4 % are divided in 11 different agricultural associations. Associations are not engaged in cacao collection and marketing (except for the Tuxtla Chico Cacao Growers Association). For this reason we recommend strengthening the organizational procedures in order to increase production, add higher value to products and increase partners' income.

Labor. 54.1 % cacao growers use labor in at least one of the following activities during the cacao crop cycle: cleansing, pruning and shade regulation. Engagement of the family in cacao activities is also important, since the rest of the farmers (45.9 %) carry out these activities using family labor.

Agronomic aspects. Over 50 % cocoa plots are in plain regions, which facilitates crop activities because soils are deeper, fertile and less eroded. The other 50 % plots are on hills, and these are considered marginal, less productive and with poor access to technology and communication.

In Chiapas different types of cacao are grown, such as Calabacillo (also called Ceylán or Costa Rica), Guayaquil, Injerto (RIM), Lagarto, Tabasco, also known as white almond landraces. 14.7 % growers in Chiapas harvest white almond cacao. This percentage results from a higher level of susceptibility to diseases. Accordingly, Córdova (2005) pointed out that one of the main constraints to cacao production and conservation are diseases. On the other hand, Ramírez (1997) mentions the importance of these cacaos, since they are the basis for genetic improvement of ordinary cacaos (foreigner).

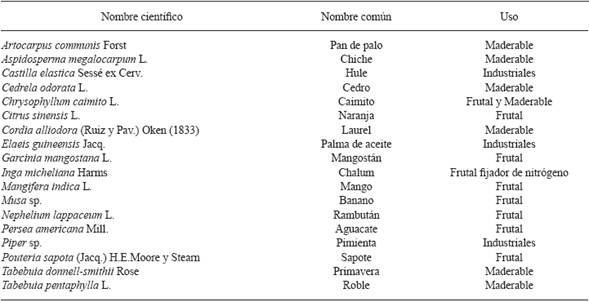

Cacao plantations in Chiapas are 36 years old on average. Avendaño et al. (2011) found similar data in his research and reports that plantations are over 25 years old and only 4 % farmers hold new plantations. According to León (1987), a cacao plantation can be productive for as long as 25-30 years. There is no doubt that the age of the current cacao plantations is one of the reasons contributing to the decline of the crop, so it is urgent to renew plantations using a 4x4 m planting framework. Cacao crop needs shade and this may vary according to species and genotypes used and environment characteristics. In Chiapas, cocoa growers use timber, fruit and native trees (Table 2). Shade plays an important role as a buffer against weather conditions (Beer, 1988; Roa et al. 2009; Salgado et al. 2007), as well as a source for food and income, space for biodiversity conservation and management, carbon capture and water infiltration (Beer, 1988; Parrish et al., 1999).

Table 2 Species of shade trees used in cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) plantations in the Soconusco and northern Chiapas, Mexico, regions.

Only 38 % cocoa growers use shade trees and regulate the shade. The low percentage of growers who allocate resources to maintaining and regulating shade within their cacao plantations is explained by the fact that most of them believe that shading is of little benefit to the crop, which generates production costs and is not profitable.

Most cacao growers (97.2%) weed manually to remove weeds from their plantations. This task is achieved during the rainy season because it is at that time when weeds tend to grow and affect the crop.

Only 32 % of the interviewed growers apply chemical fertilizer, for which they use urea (46-00-00); 4.6 % uses compost. Composts are made of plant residues from pruning, shade trees canopy and the skin of the fruit harvested.

Though 50 % of the plots are in flatlands, only 15.6 % growers said that they drain their plots to remove the excess of water accumulated during the rainy season and thus prevent disease outbreaks (Moore-Landeker, 1996).

The current average yield of cacao in Chiapas is 118 kilograms per hectare and ranges from 0 kg ha-1 to 800 kg ha-1. Cocoa is harvested throughout the year. However, most of the harvest takes place in June, October and November.

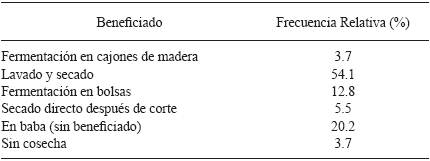

Profit is essential and decisive to harvest beans of good quality (it provides the basic principles of taste and scent) and for farmers to make a profit from its marketing in national and international markets. Cocoa processing includes fermentation, washing and drying (Table 3). The fermentation process is traditionally carried out by placing the cocoa beans in wooden boxes under controlled conditions.

Table 3 Processing of cacao beans production (Theobroma cacao L.) in the Soconusco and northern Chiapas, Mexico, regions.

Marketing. 76.1 % cocoa growers sell their harvest as dried beans after processing, while 20.2 % sell their production as mucilaginous pulp (Table 3). Selling fresh cacao is a fast way to market their produce to intermediaries without having to process it.

Cacao can be marketed through different means. 60.5 % growers sell their produce to intermediaries, 33 % through associations, and only 2.8 % sell their cacao directly to end consumers as artisanal chocolate, for which they make greater profits. Only 3.7 % reported not having harvest. The price per kilogram of dry cacao beans during 2013-2014 was $30.00 pesos. According to 55 % growers, this price is lower than that they were paid in the previous cycle. This fact shows that price is another factor contributing to the decline of the crop.

Parasitological aspects. Diseases are the main parasitological problem that limits cacao production for they cause losses of up to 100 %, if there is no control. According to the visits and interviews conducted, moniliasis was found in 100 % plots; moniliasis is a fungal infection caused by Moniliophthora roreri (Cif y Par.) Evans et al. The disease is considered a serious threat to the cocoa crop in Mexico (Phillips, 2004; Phillips et al., 2006; Ramírez, 2008); in 67 % plots black spots on pods, caused by Phytophthora capsici Leonian, were observed; in 10.1 % plots branch galls were detected, which are associated to Fusarium sp. This is a potentially important disease worldwide (Ploetz, 2007); 3.7 % showed anthracnose symptoms on leaves and fruits; this disease is associated to Colletotrichum gloeosporioides Penz; in 0.9 % of the plots wilt of cacao was detected, which is caused by Ceratocystis cacaofunesta (Engelbrecht & T.C. Harr.), and was associated to borers.

Our results allowed us to identify moniliasis as the main parasitological factor that has influenced the loss of cacao production and biodiversity in Chiapas, given that, when the disease destroys their production, farmers lose interest and leave their plantations or replace them with fruit crops. Also, cacao becomes an unprofitable crop because of the cost of spray program and control measures needed to curb the disease.

Overall, growers achieve agronomic activities and apply chemical fertilizers to control diseases in their plantations. 46.8 % farmers use chemicals to control diseases; this practice includes cutting infected fruit, pruning plants and shade regulation. For such control, farmers use copper, bicarbonate of soda, chlorine, lime, ashes or insecticides, which are incorporated into the same application. Growers also said that they apply a mix of sulphate and calcium, according to local agricultural technicians' recommendations. Those who apply these products said that they do not see a disease control but a decrease in production. Murillo and González (1984) said that an effective disease control largely depends on the selection of appropriate fungicides. Phillips (2004) suggested that the control of moniliasis is not effective, and that, if undertaken, it can be considered uneconomical. In Mexico, Torres et al. (2013) kept moniliasis under control using azoxystrobin (Amistar(r) 50 % WG, Syngenta Crop Protection AG, Suiza). However, the best and most economical option to control cacao diseases is genetic improvement (Avendaño et al., 2013). Only one grower reported to use genetic control by empirically selecting plants resistant to Phythopthora sp., and using them for grafting. Currently, the same grower selects and tests materials resistant to Moniliophthora roreri, with support from the Mexican Institute of Forestry, Agriculture and Livestock (INIFAP).

Cocoa growers do not consider pests as a restriction to cacao production. Animal pests identified as a problem and their occurrence in the production plots sampled included squirrels (7.3 %), woodpeckers (4.6 %) and gophers (3.7 %). These pests damage fruit and reduce yields. Among insect pests, ants of the genus Atta (33.9 %) were the most commonly found; they are characterized by drilling galleries in the trunks and causing changes that affect the emergence of floral bearings, and also eating the skin of the fruit. In contrast, Goitia et al. (1992) mentioned that ants can contribute to cacao pollination and to the biological control of trips. Other insect pest detected during visits was aphids Toxoptera aurantii (Boyer de Fonscolombe) with 11% of occurrence. Aphids feed on terminal portions of shoots and the youngest leaves, which results in deformities. Branch and stem borers (Xyleborus ferrugineus Fabricius, Xylosandrus morigerus Blandford, Hypothenemus birmanus Eichhoff, Corthylus minutissimus Schedl, Taurodermus sharpi Lenis, Hypothenemus interstitialis Hopkins) and budgerigar (Vanduzea segmentata Fowler) were found in 5.5 % of the sampled plots. These borers had been previously reported in cacao by Equihua (1992) and Pérez et al. (2009). Thrips (Selenothrips rubrocintus Giard) were detected in only 3.7 % plots. Their damage was characterized by scratching and sap suction that cause leaves, flowers and small fruits to fall. When attacked by thrips plantlets often die. Thrips can also damage ripe fruit by developing dark spots on pods, thus making difficult to determine their maturity level and affecting fruit appearance. Spittlebug (Clastoptera laenata Fowler) was detected in 3.7 % plots. This hemipteran produces a foam layer that prevents the normal development of flowers, which, in turn, remain inactive and often die.

Farmers do not carry out any kind of management to control animal and insect pests, except for ants, that are controlled with Parathion-methyl(r), a commercial product recommended by local agrochemical suppliers. According to this study, pests have not influenced a change in the use of varieties or adoption of other crops.

Morphological and molecular details for diagnosing diseases and identifying pests will be described in another document for reasons of space.

Cacao in the state of Chiapas can be considered a declining crop. The main cause of this is the phytosanitary, particularly a disease commonly known as moniliasis. This disease directly affects production and harvest, and increases production costs; for this reason farmers have lost interest in growing cocoa. In addition, there are other economic, social, cultural and agronomic aspects, including increased production costs, lower yields, poor economic return, low educational level, growers with little education and training, little participation by women, limited membership in farmer association, little access to improved varieties and small production units. It is a shame that a crop such as cacao, which is part of our history, our culture and plays an important role within the ecosystem is now declining. For this reason, it is crucial to implement strategies for alleviating the problems that limit its production and make it once again a viable financial source that is sustainable and attractive to farmers.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the following for their support to this research: Chiapas Cacao Growers, Cacao Production Associations, the Mexican Institute of Forestry, Agriculture and Livestock (INIFAP)), the National Council for Science and Technology-Chiapas (COCYTECH), and the National System for Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (SINAREFI).

REFERENCES

Agarwal B. 1992. The Gender and Environment Debate: Lessons From India. Feminist Studies 18(4): 119-158. [ Links ]

Aguirre MJF. 2009. Historia y situación actual del cacao. En: Moisés Alonso y Aguirre Juan Francisco. Manual de producción de cacao. p.109. INIFAP, México. [ Links ]

Avendaño ACH, Mendoza LA, Hernández GE, López GG, Martínez BM, Caballero PJF, Guillen DS. y Espinosa ZS. 2013. Mejoramiento genético participativo en cacao (Theobroma cacao L.). Agroproductividad 6(5): 71-80. [ Links ]

Avendaño ACH, Villareal FJM, Campos RE, Gallardo MRA, Mendoza LA, Aguirre MJF, Sandoval EA,. Espinosa ZS 2011. Diagnóstico de cacao en México. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Texcoco, México. 80p. [ Links ]

Beer JW. 1988. Litter production and nutrient cycling in coffee (Coffea arabica) or cacao. (Theobroma cacao) plantations with shade trees. Agroforestry Systems 7(2):103-114 [ Links ]

Córdova AV. 2005. Organización campesina en la reconversión del cacao tradicional a orgánico en Tabasco, México. En: Aragón A, López JF, Tapia AM. Manejo Agroecológico de Sistemas. Dirección de fomento editorial. Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. Primera Edición. 180. [ Links ]

Córdova AV, Sánchez HM, Estrella CNG, Sandoval CE, Ortiz GCF. 2001. Factores que afectan la producción de cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) en el ejido Francisco I. Madero del Plan Chontalpa, Tabasco, México. Universidad y Ciencia 17(34): 93-100. [ Links ]

Cortez R, y Pizarro A. 2001. Construyendo el desarrollo sostenible con equidad de género. En La ineludible corriente. Políticas de equidad de género en el sector ambiental mesoamericano. Comp. y ed. Lorena Aguilar. UICN, 1a. Ed. San José, Costa Rica. 25 -33. [ Links ]

Díaz JO, Aguilar AJ, Rendón MR. y Santoyo CVH. 2013. Situación actual y perspectivas de la producción de cacao en México. Ciencia e Investigación Agraria 40(2): 279-289. [ Links ]

Engler, A., and Toledo, R. 2010. An analysis of factors affecting the adoption of economic and productive data recording methods of Chilean farmers. Ciencia e Investigación Agraria 37(2):101-109. [ Links ]

Equihua MA. 1992. Coleópteros Scolytidae atraídos a trampas NTP-80 en el Soconusco, Chiapas, México. Folia Entomológica Mexicana 84: 55-66. http://www.barkbeetles.info/pdf_assets/Equihua_1992_FEM_84.pdf [ Links ]

Ghiglione R, Matalón B. 1989. Las encuestas sociológicas. Teoría y práctica. Editorial Trillas, México. 318 p. [ Links ]

Goitia W, Bosque C. and Jaffe K. 1992. Interacción hormiga-polinizador en cacao. Turrialba 42(2): 178-186. [ Links ]

González VW. 2005. Cacao en México: competitividad y medio ambiente con alianzas (Diagnóstico rápido de producción y mercadeo). United States Agency International Development. Chemonics International Inc. 93 p. [ Links ]

Legislación Agraria. 2004. Legislación Agraria. DOF 09-04-2012. http://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/13.pdf [ Links ]

León J. 1987. Botánica de los cultivos Tropicales. IICA. San José, Costa Rica. 337 p. [ Links ]

Maier HE. 2003. Construyendo la relación entre la mujer y el medio ambiente: Una exploración conceptual, en: Esperanza, Tuñón (coord.). Género y medio ambiente. El Colegio de la Frontera Sur. Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, Plaza y Valdés, México: 27-44. [ Links ]

Motamayor JC, Risterucci AM, López PA, Ortiz CF, Moreno A and Lanaud C. 2002. Cacao domestication I. the origin of the cacao cultivated by the Mayas. Heredity 89: 380-386. [ Links ]

Moore-Landecker E. 1996. Fundamental of fungi. Prentice Hall. Nueva Jersey, EUA. pp. 238- 367. [ Links ]

Murillo D, González LC. 1984. Evaluación en laboratorio y campo de fungicidas para el combate de la moniliasis del cacao. Agronomía Costarricense 8: 83-89. [ Links ]

Nájera CMI. 2012. El mono y el cacao: la búsqueda de un mito a través de los relieves del Grupo Serial Inicial Chichen Itza. Estudios de cultura Maya 39: 133-172. [ Links ]

Parrish J, Reitsma R, Greenberg R, MacLarney MR, and Lynch J. 1999. Los cacaotales como herramienta para la conservación de la biodiversidad en corredores biológicos y zonas de amortiguamiento. Agroforestería en las Américas 6(22): 35. [ Links ]

Pérez CM, Equihua MA, Romero NJ Sánchez SS, García LE, Bravo MH. 2009. Escolítidos (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) Asociados al Agroecosistema Cacao en Tabasco, México. Neotropical Entomology 38 (5): 602-609. http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1519-566X2009000500007 [ Links ]

Phillips MW. 2004. La moniliasis del cacao: una seria amenaza para el cacao en México.In: Simposio Nacional sobre enfermedades tropicales. Resúmenes de ponencias. Tabasco, México: 91-99. [ Links ]

Phillips MW, Coutiño A, Ortiz CF, López AP, Hernández J and Aime MC. 2006. First report of Moniliophthora roreri causing frosty pod rod (moniliasis disease) of cocoa in Mexico. Plant Pathology 55 (4): 584 [ Links ]

Ploetz RC. 2007. Cacao diseases: important threats to chocolate production worldwide. Phytopathology 97 (12): 1634-1639. http://apsjournals.apsnet.org/doi/pdf/10.1094/PHYTO-97-12-1634 [ Links ]

Quispe A. 2013. El uso de la encuesta en las ciencias sociales. Ediciones D.D.S. México D.F. 105 p. [ Links ]

Ramírez DFJ. 1997. Sistema agroindustrial del cacao en México y su comportamiento en el mercado. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. México. 161. [ Links ]

Ramírez GSI. 2008. La moniliasis un desafío para lograr la sostenibilidad del sistema cacao en México. Tecnología en Marcha 21(1): 97-110. http://tecdigital.tec.ac.cr/servicios/ojs/index.php/tec_marcha/article/view/1343 [ Links ]

Roa RHA, Salgado MM y Álvarez HJ. 2009. Análisis de la estructura arbórea del sistema agroforestal de cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) en el Soconusco, Chiapas, México. Acta biológica Colombiana 14(3): 97-110. [ Links ]

Sagarpa. Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación. 2013. Servicio de información agroalimentaria y pesquera. http://www.siap.gob.mx/index (consulta, julio 2013). [ Links ]

Salgado MM, Ibarra NG, Macías SJE, López BO. 2007. Diversidad arbórea en cacaotales del Soconusco, Chiapas, México. Interciencia 11(32): 763-768. http://www.scielo.org.ve/pdf/inci/v32n11/art09.pdf [ Links ]

SIAP. 2014. Cierre de la producción agrícola por cultivo SAGARPA. México. Servicio de información agroalimentaria y pesquera (SIAP). Consultado en línea en http://www.siap.gob.mx/cierre-de-la-produccion-agricola-por-estado/ [ Links ]

Suárez SRB, Zapata ME, Ayala CR, Cárcamo TN, y Manjarrez RJ. 2011. ¿...y las mujeres rurales?. Indesol. GRMTRAP A.C., México: 251 p. [ Links ]

Torres CM, Ortíz GCF, Téliz OD, Mora AA y Nava DC. 2013. Efecto del azoxystrobin sobre Moniliophthora roreri, agente causal de la moniliasis del cacao (Theobroma cacao). Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología 31(1): 65-69. [ Links ]

White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, and Taylor JW. 1990. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis M A, Gelfand D H , Sninsky J J, White T J, editors. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.: 315-322pp. [ Links ]

Received: June 11, 2015; Accepted: July 07, 2015

text in

text in