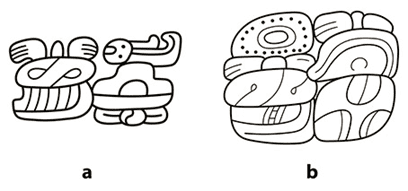

In 2008, David Stuart (2008) presented evidence for reading an undeciphered sign in the Maya script as a syllabic sign Co, with an unknown consonant and the mid-back vowel o. The composite glyph under discussion consists of three graphic elements. The upper element resembles Diego de Landa’s ma syllable (G. Stuart, 1988: 25). The central element resembles the TAL logogram. The lower element varies: some examples feature a “fish fin” design (mostly in Early Classic examples, Figure 1a), and others a so-called “shiner” marker (mostly in Late Classic examples, Figure 1b). Stuart identified four examples of the glyph in the contexts of different Co syllables, namely, mo, lo and ko. One more context with the ko syllable was identified by Christophe Helmke on Copan Stela 13 (see comments in G. Stuart, 2008). The fact that the sign under discussion always appears in combination with other syllabic signs strongly suggests a syllabic reading value (D. Stuart, 1995: 47-49). As D. Stuart (2008) noted, the fact that the adjacent signs are Co syllables strongly suggests the mid-back o vowel as part of its syllabic value (Zender, 2017: 9). The best candidate for the reading seems to be tzo. This interpretation works perfectly on Tortuguero Monument 6, resulting in the collocation ˀu-tzo-lo-wa “he/she puts in order (periods of time)”, cf. *tzol- “(t.v.) to put in order, count” (see lexical entries, reconstructions and orthographic conventions in the appendix below). The other contexts remained unexplained, however.

Drawings by Sergei Vepretskii.

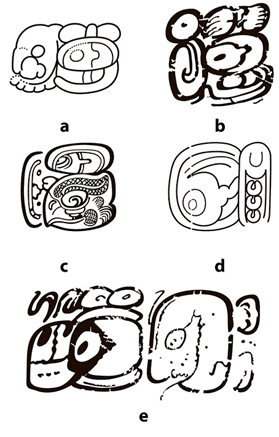

Figure 1 The examples of the Co syllable noticed by Stuart: (a) X-lo-?-WINKIL?, the earspool of Altun Ha (after Peter Mathews in D. Stuart, 2008: Example a; (b) mo-X-no?-cha/se, Tortuguero Monument 8, Block G (after unpublished photographs by Elisabeth Wagner and Sven Gronemeyer).

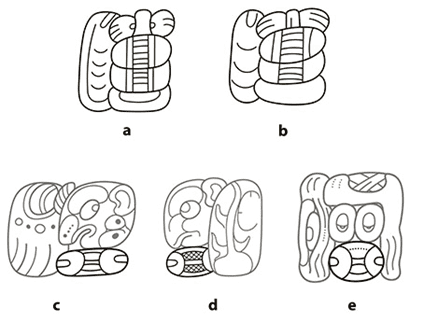

During the workshop “Grammar of Hieroglyphic Maya”, held during the 18th European Maya Conference in Brussels in 2013, one of the authors (Davletshin) presented two examples of the sign under discussion, attested as part of a predicate on two panels in the Cross Group of Palenque (Figure 2a, b). Both panels refer to the same ritual event in which six-year-old K'ihnich Kan B'ahlam II was involved. According to the interpretation proposed at that time, the le syllable and the ligature of the signs tzo and ko give us letzok, the optative mood of the intransitive verbal root letz-, attested in both Ch'orti' and Ch'ol as “to go up, climb, ascend” (Stuart, 2006: 130). On the panel from the Temple of Cross, the glyphic collocation is followed by the sequence ta-b'a-la b'o-jo TEˀ-le , ta b'alal b'ojteˀel. This can be interpreted as “at the forbidden city”, literally, “at a place protected by wooden walls” (Davletshin and Vepretskii, 2017; Stuart, 2006: 130-131). It was suggested that the optative in this collocation was intended to show that the described action had taken place in a secluded room, where people were unable to see the actor. This use of the optative mood is attested in many languages all over the world. Thus, letzok ta b'alal b'ojteˀel can be translated as “they say he ascended to a place protected by wooden walls” or “he allegedly ascended to the place”.

Drawings by Sergei Vepretskii.

Figure 2 The sign under discussion compared with the ko syllable on Palenque Cross Group Panels: (a) le-X, Temple of Cross, I1 (after Linda Schele in Stuart, 2006: 131); (b) le-X, Temple of Sun, I2 (after Linda Schele in Stuart, 2006: 170); (c) b'a-ch'o-ko, Temple of Foliated Cross, K3 (after Linda Schele in Stuart, 2006: 150); (d) ch'o-ko-TAK, Temple of Sun, M2 (after unpublished photographs by Ivan Savchenko and Yuriy Polyukhovych); (e) ˀu-ch'o-ko-K'AB'Aˀ, Temple of Sun, A12 (after unpublished photographs by Ivan Savchenko and Yuriy Polyukhovych).

A possible [Ce] sign

The suggested interpretation of the Palenque examples is attractive. However, the graphic element inscribed into the supposed tzo syllable is distinct from the other syllabic signs ko attested on the same panels (Figure 2c, d, e). In both examples under consideration, the graphic element is doubled and lacks the characteristic dots on the sides that indicate holes in the turtle shell represented by the ko syllable, derived from Proto-Mayan *kok ‘turtle’ (Houston, Robertson and Stuart, 2000: 328). The example on Copan Stela 13 (Figure 3a) is suspiciously similar in this respect: the ko syllables (B7, D3 and D8) differ from the supposedly equivalent element inscribed in the tzo sign (Figure 3b, c). The meaning of the glyphic collocation in this text is obscure, but, importantly, the alleged ligature of the syllables tzo and ko precedes a syllable he. Basing himself on this, one of the authors (Vepretskii) questioned the original proposal and suggested that the alleged ligature of the syllables tzo and ko is a previously unrecognized Ce syllable. Two graphic designs (A and B) with the same reading value are expected to be in free distribution, and the probability of sign substitution between A and B should be close to the probability obtained by multiplying the probabilities of occurrence for the designs A and B in the parallel texts (Davletshin, 2017: 69-70). This condition is not satisfied when we compare the distribution of the composite sign with the TAL-like element with the distribution of the composite sign with the ko-like element. Because of this, we assume that the combination of three graphic elements under discussion is a single Ce syllable for it is attested in the context of other syllabic signs involving the mid front e vowel.

Drawings by Sergei Vepretskii after Linda Schele, <http://research.famsi.org/schele.html>, #1040.

Figure 3 The sign under discussion compared with the ko syllable on Copan Stela 13: (a) X-he, E6; (b) ˀu-ch'o-ko-K'AB'Aˀ, B7; (c) ˀu-cho-ko-wa?, D8.

Let us return to the example from Palenque. Importantly, the descriptions of the rituals implemented by K'ihnich Kan B'ahlam II mention another event that occurred 536 days later. It is spelt as ju-b'i jub'-i on the panel from the Temple of Cross and as ju-b'u-yi jub'uuy on the panel from the Temple of Sun; both are based on the intransitive verb jub'- “to go down” and can be translated into English as “he descended” (see below for a dialectal interpretation of the form iub’-i). This parallel strongly speaks in favor of the suggested interpretation letz- “to ascend,” for the future king goes up to a secluded place and later returns from it by coming down. Thus we suggest the reading value tze for the sign. In fact, the second e vowel of the verb can be interpreted as the thematic vowel attested in Ch'orti' letz-e “to climb, mount” (Wichmann, 1999: §2.2). Both syllabic spellings and cognates in Cholan languages imply that the suffix terminates in a bare vowel (see, for example, Kaufman and Norman, 1984: 93, 102-104); the same applies to two other thematic suffixes attested in the script, although all lexical roots and derivational suffixes end with a consonant in Hieroglyphic Mayan, as well as in most Mayan languages, cf. hul-i “he/she arrived (at this place)” and ˀu-tz'ihb'-a “he/she wrote (it)”. Interestingly, *letz- “(i.v.) to go up”, *b'ojteˀ “(n.) wooden wall” and *jub'- “(i.v.) to go down” all are low-level innovations in Cholan languages: *b'ojteˀ is restricted to the Western Cholan languages Ch'ol and Chontal, and *jub'- is attested among today’s Mayan languages only in Ch'ol. Ch'ol is spoken in close proximity to Palenque today. These three words are likely dialectal isoglosses in Hieroglyphic Mayan. The lexical roots *letz- and *jub'- replaced Proto-Cholan *t'ab'- “(i.v.) to go up” and Proto-Mayan *ˀehm- “(i.v.) to go down”, respectively (for their distribution see the appendix below). The nonstandard thematic suffixes in the intransitive verbs letz-e “he/she went up” and jub’-i “he/she went down” are likely to be dialectal traits, too.

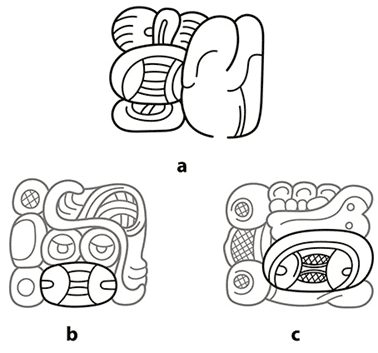

The unprovenanced celt hosted in the Fidel Tristán Jade Museum features the same syllabic sign preceded by an ˀu syllable (Figure 4b). Unfortunately, the preceding block and the following one are not preserved. In other words, the context is unclear and we are unable to suggest any interpretations.

Drawings by Sergei Vepretskii.

Figure 4 More examples of the sign under discussion: (a) K'INICH-? X-na?, Caracol Stela 16, B17-A18 (after the photograph of Penn Museum, Philadelphia, 51-54-5, <https://www.penn.museum/collections/object/75084>); (b) ˀu-X, unprovenanced celt hosted in the Fidel Tristán Jade Museum (after David Mora-Marín, 2001: Fig. 16); (c) ˀu-X-li, Tonina Monument 171, F1 (after unpublished photographs by Sergei Vepretskii).

Another example is attested as part of a personal name on Caracol Stela 16, block A18 (Satterthwaite and Willcox, 1954: Fig. 16; Beetz and Satterthwaite, 1981: Fig. 15a, b). The name belonged to the grandfather of the person who assisted the king Tum ˀOl K'ihnich I during the celebration of the period ending in 534 CE. The nominal phrase consists of the signs K'INICH and a “Canine Head” (B17), and the proposed tze syllable appears in combination with another sign (A18) (Figure 4a). The latter looks like a young male head with black marks on his cheek, similar in appearance to the Tonsured Maize God sign. The Tonsured Maize God sign possesses two reading values - ˀIXIM “grain corn” and na (Zender, 2014). The cognates of tzeˀn- “to laugh, smile” and *tzehn- “to provide food; sustenance” are widely attested in Lowland Mayan languages. However, both the identification of the Tonsured Maize God sign and the interpretation of the nominal phrase are problematic.

Early Classic examples of both tzo and tze syllables feature a kind of striation in the lower part, similar to the “fish fins” of the ka syllable (Figure 1a, 4a); meanwhile, in Late Classic examples, this striation is replaced with the “shining” marker (Figure 1b, 3a).

Another, rather problematic example comes from Tonina Monument 171 (Graham et al., 2006: 116), where two persons are depicted playing ball in 727 CE. The captions identify the player on the left as the Tonina king K'ihnich B'aknal Chaahk (ruled 688-704>), who was already dead by the moment of the depicted event. The person in the right was identified by David Stuart (2013) as the Calakmul king known under the nickname Yuknoˀm Toˀk' K'awiil (698-731>). The Tonina king K'ihnich ˀIhch'aak Chapaaˀt (723-739>) is mentioned in connection with the Calakmul ruler. The relational phrase between the two (F1) contains a composite sign similar to the proposed tze syllable (Figure 4c). It is different from other known examples, however, because of two graphic peculiarities. First, the central, ko-like element includes additional vertical lines unattested elsewhere. Second, the lower part is replaced by the li syllable. The sign on Tonina Monument 171 might be a graphic variant of the tze syllable, whereby the collocation can be read ˀu-tze?-li, ˀu-tzeel, “beside him, abreast of him”, cf. Proto-Mayan *tzehl “side”. As Stuart (2013) has noted, the scene from the year 727 depicts a long-deceased Tonina ruler playing ball with a foreign Calakmul lord, with the current king named but not even shown. He suggests that the Calakmul king could have participated in a ballgame earlier, when K'ihnich B'aknal Chaahk was alive, and that the monument commemorated this past event. The scene might depict a ritual re-enactment of the ballgame in which the long-deceased persons were impersonated by the current kings. Similar impersonations of the dead are widely practiced among Pisaflores Tepehuas and Mecapalapa Totonacs of today’s Southern Huasteca (Davletshin, fieldwork data from 2007).

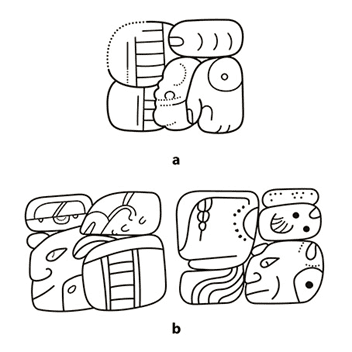

The suggested tze syllable might be also attested on Nim Li Punit Stela 15, P2 (Grube, MacLeod and Wanyerka, 1999: Fig. 2; Wanyerka, 2003 Fig. 29):. The central part of the sign features a doubled ko-like element, with the upper and lower elements missing (Figure 5a). It is followed by the le syllable. This collocation is likely a part of a personal name, perhaps, related to Proto-Cholan *tzeel “crest”. The same design without the upper and lower elements can be seen on the so-called Akab Dzib Lintel from Structure 4D1 in Chichen Itza (G2). Here, it forms part of a woman’s name, following the me syllable and resulting in the reading ˀi-ˀIX-me-tze? TUN-ni, ˀIx Metz Tuun (Figure 5b). Guido Krempel (personal communication, 2020) has suggested to us that the same graphic design is attested in the emblem glyph of Nakum. However, in this particular context the sign behaves like a logogram.

Drawings by Sergei Vepretskii.

Figure 5 Some variants of the sign under discussion: (a) X-le-?-k'o, Nim Li Punit Stela 15, P2 (after photograph by Bruce Love in Prager and Braswell, 2016: Fig. 8); (b) ˀi-ˀIX-me-X TUN-ni K'UH-lu-ˀIXIK, Akab Dzib Lintel from Chichen Itza, G2 (after rubbings by John Denison, <http://www.famsi.org/reports/95099/AkabTzibLintelFront.pdf>).

We suspect that the examples from Nim Li Punit and Chichen Itza represent a late variant of the sign under consideration, reduced to the central ko-like element. Interestingly, the same graphic development can be observed for the proposed tzo syllable, as has been discussed by Albert Davletshin, Dmitri Beliaev and Guillermo Kantun Rivera in 2014. The emblem glyph of Ek' Balam consists of the TAL-like design combined with the lo syllable, giving us tzo-lo ˀAJAW (Helmke, 2020: 268). The TAL-like sign in these examples is rotated 90 degrees; importantly, too, a few examples show an appendage in the lower part of the sign (Ek' Balam Capstone 14, Mural of the 96 Glyphs and Mural C, see Figure 6). Similar graphic designs frequently undergo analogical developments in Maya script (see many examples in Lacadena, 1995; Davletshin, 2003).

Drawings by Sergei Vepretskii.

Figure 6 Ek' Balam emblem glyph: (a) X-lo-ˀAJAW-wa, Mural C, U (after photograph in Lacadena, 2003: Fig. 20b); (b) X-[lo]-ˀAJAW-[wa], Mural of the 96 Glyphs, F'3 (after Lacadena, 2003: Fig. 18e).

Another possible [tze] sign

One more sign resembles the proposed tzo and tze syllables, but it differs because of a distinctive graphic element in the centre (Figure 7a, b). It is attested on Tonina Monument 84 (Graham and Mathews, 1996: 114) and on the painted vase K5855 (Marc Zender, personal communication, 2018). The central element resembles the “Eye” design of the logographic signs ˀUT “eye” and ˀILA- “to see”. On Tonina Monument 84 (Figure 7a), it follows the syllable pe (Davletshin and Beliaev, 2001). On K5855 (Figure 7b), it follows the syllable we (Zender, Beliaev and Davletshin, 2016). Both examples likely spell personal names. Thus, the contexts are obscure and can be subjected to three different interpretations. Firstly, the sign might be another variant of the tze syllable. Secondly, it might be an unknown Ce syllable, t'e, ch'e, xe or, less likely, p'e. Thirdly, the sign might be an unknown Ce syllable written in a ligature with the proposed tze syllable.

Drawings by Sergei Vepretskii.

Figure 7 “Eye” syllable: (a) pe-tze?+X, Tonina Monument 84, B (after photograph by Peter Mathews in Graham et al., 2006: 114); (b) we-tze?+X, unprovenanced Codex-style vessel, K5855, C4 (after photograph by Justin Kerr, 1989 <http://research.mayavase.com/kerrmaya_hires.php?vase=5855>); (c) ˀu-X-b'e, Calabaza de Acanceh, A2 (after unpublished photographs by Sergei Vepretskii); (d) X-le, Xcalumkin Panel 3, B2 (after photograph by Harry Pollock in Graham and Von Euw, 1992: 181); (e) ˀAJ-we-X pe-ya?, fleur-de-lis cylinder vase (after photograph in Robicsek and Hales, 1981: 200).

The second and third solutions seem more plausible because the “Eye” syllable is also attested in three other contexts, although we were unable to find any likely lexical glosses for these contexts in Mayan dictionaries. First, the “Eye” syllable is written as part of a name-tag on the so-called Calabaza de Acanceh (Voss and Kremer, 2000: Fig. 1, A1-A2): yu-xu-lu-li ˀu-(C?)e-b'e y-uxulil ˀu-Ceb', “the carving of his X”, where ˀu-(C?)e-b'e refers to the inscribed object (Figure 7c). Second, the “Eye” syllable is written as part of a personal name, followed by the le syllable on Xcalumkin Panel 3 (Figure 7d). Third, the “Eye” syllable is attested with some additional elements as part of the glyphic collocation ˀaj-we-(C?)e pe-ya on the fleur-de-lis cylinder vase (Robicsek and Hales, 1981: 200). This third example suggests the possibility that the sign’s additional elements correspond to Diego de Landa’s ma and the lower element of both syllables tze and tzo. If this suggestion is correct, the complete version of the “Eye” syllable includes these graphic elements in its design, which were eliminated in later examples, sharing this particular paleographic development with the syllables tze and tzo. An “Eye” sign attested in an unclear context in Palenque (Stucco inscriptions from Temple XIX: D6) might belong to this group, too.

Diego de Landa’s <c> Syllable

The Diego de Landa alphabet includes an equivalent for the Spanish letter <c> (Figure 8a), among two dozen of other hieroglyphic signs (Tozzer, 1941; G. Stuart, 1988: 25; Kettunen, 2020: 70). The sign in Figure 8a represents an abstract design; in the second half of the 20th century, epigraphers used to refer to the sign by the corresponding number in Eric Thompson’s catalogue, T520, and sometimes by the nickname “Chuen” (Thompson, 1962; Justeson and Campbell, 1984: 340). This nickname corresponds to the Colonial Yucatec name of the eleventh day in the 20-day calendric cycle.

Drawings by Sergei Vepretskii.

Figure 8 The Diego de Landa’s <c>: (a) X from Diego de Landa alphabet (after photograph in Kettunen, 2020: Fig.10) ; (b) X-ka, Dresden Codex, P. 50 (after photograph in Grube, 2012); (c) X-ka-wa, Dresden Codex, P. 62 (after photograph in Grube, 2012); (d) standard version of X Tortuguero Monument 6, G9 (after unpublished photograph by Elisabeth Wagner and Sven Gronemeyer); (e) the head variant of X, Yaxchilan Lintel 41, B1 (after photograph by Alfred Maudslay, <https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/image/336524003>); (f) the full-figured X, Copan Str. 9N-82 hieroglyphic bench, 7 (after photograph in Zender, 2019: Fig. 3).

In the 16th century, Spanish affricates (*ʦ, *ʣ) and sibilants (*s, *z, *ʃ, *ʒ) were merging together; importantly, the process of neutralization took different paths in Castilian and Andalusian varieties of Spanish, resulting in θ and s in Castilian, and s in Andalusian (Penny, 2002: 98-103). For this reason, the letters <c>, <ç> and <tz> may refer to all six sounds in documents from New Spain, and Diego de Landa’s <c> can be interpreted as either the syllable tze or the syllable se. Hence, the reading of Diego de Landa’s <c> should be discussed here.

In the last two decades, the sign was tacitly assumed to represent the syllable se, although its phonetic reading was not reliably demonstrated until very recently (Zender, 2019). Graphological commentaries are essential for further discussion and are possible thanks to numerous Classic Mayan spellings of the fifth month, where the signs in Figure 8 are combined with the syllables ka and wa.

Firstly, the once popular nickname “Chuen” is misleading because the logograph CHUWEN “howler monkey” is similar but not identical to the sign known as T520; the latter depicts the eye of a howler monkey with an overhanging brow (Dmitri Beliaev, personal communication, 2017). A less common variant “howler monkey’s head” is also known. The non-head variant always features the brow, except when the signs CHUWEN and the so-called day sign cartouche K'IN? are conflated into ligatures. Thus, we can assume that the day sign cartouche suppresses or overlaps the monkey brow. In the Classic period, the forerunner of Diego de Landa’s <c> never included the brow element; it corresponds to the eye of the CHUWEN logograph from a graphic point of view (Figure 8b). The Postclassic version of the CHUWEN logograph does not include the characteristic brow element, but all known examples are attested in ligatures with the cartouche of day signs. Importantly, the so-called monkey eye element of the Classic period bears resemblance to the logograph WINAK “person, twenty” in the Dresden Codex (Grube, 2012: passim). The CHUWEN logograph thus merged with the WINAK logograph in the Dresden Codex.

Secondly, Diego de Landa’s <c> in his manuscript and in the Postclassic codices shows a characteristic notch in its upper portion with two “tendrils” coming out; it was regarded as a distinct sign by Thompson and designated as T562. In other words, the sign in Figure 8a belongs to the group of the so-called cleft or split signs, which includes the syllables cha, t'i? and xo, and the logographs PAˀ “split”, PAX “music” and WAˀ “to be upright” (D. Stuart, 1987; Martin, 2004; Davletshin and Bíró, 2014). The eye element of the CHUWEN logograph, however, is never split. In the Dresden Codex, all the examples of Diego de Landa’s <c> are split and look like a split WINAK “person, twenty” sign. In the Classic Period, the se syllable is not split, aside from two likely exceptions (Caracol Stela 22: L11, Dos Pilas Panel 19: P1). On the contrary, the Classic version of the cha syllable frequently features a notch resembling Diego de Landa’s <c>. Interestingly, the Postclassic descendant of the cha syllable in the Dresden Codex is never split and looks quite different from Diego de Landa’s <c>.

Thirdly, a few head variants of the sign have long been recognized in Classic inscriptions (Figure 8c, see also Yaxchilan Stela 12, D1; Kuna Lacanja Lintel 1, M5; Zender, 2019: 31). A full-figured one was recently identified by Marc Zender (Figure 8d). Both head and full-figure variants leave no room for doubt that the sign under discussion depicts a kind of insect with a “dead” head, and that the -“Chuen”- like graphic element is a characteristic spot on the head of this particular insect.

After analyzing the graphic characteristics of the sign, we can proceed with the discussion of its reading value. In the Dresden Codex, Diego de Landa’s <c> is attested in two different spellings; both refer to the name of the fifth month in the solar year as Ce-ka and Ce-ka-wa, where C stands for either s or for tz (Figure 8e, f). It has been long recognized that the former spelling corresponds to the Yucatec name of the month, attested as <tzec> in Diego de Landa’s Relación de las cosas de Yucatan and as <zec> and <zeec> in the books of Chilam Balam (Thompson, 1950: 106). The spelling Ce-ka-wa (Dresden Codex, page 62) might be intended to be read ka-Ce-wa, which is attested in many Classic inscriptions. This form has been compared to the month name <cazeu> in a colonial document from Alta Verapaz, Guatemala (Thompson, 1932). The month names in this document are probably Cholan in origin, although they are followed by a text in Q'eqchi'. The same name is attested as <kazeu> in a Poqomchi’ list from 1906 (Thompson, 1950: 106).

In Classic inscriptions, the name of the month is written as ka-Xe-wa, with a few underspellings of the last consonant ka-Xe (Yaxchilan Lintel 41, B1) and three examples from the Northern Yucatan where it is spelt ku-Ce-wa (Xcombec, Monument 1, A2 and C1; Itzimte Bolonch'en, Stela 4; see Lacadena and Davletshin, 2013: 11; Galeev, 2017: 81). Thus, the spelling ka-Ce-wa is to be interpreted as the Cholan name of the month in the Dresden Codex and Ce-ka as its Yucatec dialectal form (Lacadena and Wichmann, 2002). Diego de Landa’s spelling of the month name is heavily distorted and likely to be Ce-wa.

Unfortunately, the meanings of both month-names are obscure, and the data from the Dresden Codex cannot clarify the phonetic reading of the sign because <c>, <tz> and <z> could be read as both s and tz. Fortunately, Marc Zender has been recently able to disambiguate the phonetic reading of the sign thanks to two glyphic contexts from Classic Period. One is the causative form ˀu-t'ab'se “he/she made it lifted”, written as ˀu-T'AB'-Ce on the hieroglyphic bench from Copan Structure 9N-82, cf. *t'ab'- “(i.v.) to go up” (Zender, 2019). The causative suffix is widely attested in Mayan languages, with *-se being one of its allomorphs, cf. Ch'orti' t'ab'se and Ch'olti' <tabse> “(t.v.) elevate”. The other context is less secure; it is the personal name of a warrior from Pomona ˀAj-K'eˀsem-Toˀk' “He of Sharpen(ed) Flint”, written as ˀaj-k'e-Xe-me-TOK' on La Mar Stela 3, C2-3, and Piedras Negras Stela 12, D15, cf. *k'eˀs “(adj.) sharp, stiff” (Zender, 2017: 24-28). Marc Zender has also proposed that the reading value of the sign is acrophonically derived from Proto-Cholan *ses “bird louse” (Zender, 2019: 31). These three arguments indicate that the phonetic reading of the sign includes the consonant s; the vowel e is also supported by the phonetic substitution of the TELES logograph as te-le-Xe, “Jesus Christ lizard (Basiliscus sp.)”. In modern Mayan languages, the last consonant of the words for “basilisk” is found in sound-symbolic alternations, preventing us from identifying the Classic Mayan consonant (Tzotzil telex, Tzeltal t'ehlech and t'erech, Davletshin, 2011).

Another sign in the Dresden Codex was considered a head variant of Diego de Landa’s <c> and read tze (Bricker, 1986: 148; Schele and Grube, 1997: 120-121). This sign is not split, in contrast to the syllable se, but depicts a human head featuring the monkey eye element that also could be WINAK element (Figure 9a). One context is attested in six examples (Dresden Codex, pages 15a-b and 16c). Various deities are shown upside-down or seated: one, the rain god Chaahk, holds a sprouting plant in its hands as if he were sowing crops. The accompanying texts record “ˀu-pa-k'a-ja X-ni, a name of a deity an augury”. Victoria Bricker equated the sign to Diego de Landa’s <c> and interpreted the passage as ˀu-pa-k'a-ja tze-ni ..., ˀu-pak'aj tzeen ... , “such-and-such deity planted sustenance” (cf. *pak'-“(t.v.) to plant” and *tzehn- “(t.v.) to feed”).

Drawings by Sergei Vepretskii.

Figure 9 The head sign with the monkey eye element. (a) X-ni, Dresden Codex, P. 15-a (after photograph in Grube, 2012); (b) X-ye-la, unprovenanced Early Classic jade celt K199a, A4 (after photograph by Justin Kerr, 1989 <http://research.mayavase.com/uploads/kerrfolio/hires/199a.png>); (c) X-ta-no-ma, Copan Altar U, I2 (after photograph by Alfred Maudslay, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/image/828772001>).

The suggested interpretation is attractive, although *tzehn- is a transitive verb root, the suffix-less derivations “fostering, support” and “adopted child” are occasionally attested in Yucatecan languages. Nevertheless, the sign under discussion never substitutes for Diego de Landa’s <c>, indicating that the two signs possess different reading values. The ni syllable in all six attested spellings suggests that the sign has a syllabic value, perhaps tze. Three other attested contexts - 6-X-ni (page 2b), mu?-X (pages 51b and 55b) and X-WINKIL (pages 49c, 72b,c and 73c) - cannot be interpreted and actually disfavour the reading value tze (for the reading WINKIL suggested by David Stuart, see Houston and Schnell, 2018). It still is possible that the sign is a logograph TZEN “support, care” and that its reading value, whether logographic or syllabic, has nothing to do with the discussed lexical entry. Importantly, only one of six deities depicted by the discussed glyphic passage holds a plant in its hands.

It should be mentioned that a head sign with the monkey eye element covering its eye and top of the head also forms part of a personal name on two unprovenanced Early Classic jade celts (Figure 9b). The following examples are found: ma-X-ye CHAN-na-YOP-ˀAT and ma-X-ye-la CHAN-na-YOP-ˀAT, “(The rain god) Yopˀaat is not (doing something) in the sky”. Alternately, the apparent ma syllable could actually be a part of X, because Diego de Landa’s ma also constitutes part of different syllabic and logographic signs: ma, no/TINAM, tza, tzo, tze, tz'o, tz'e and K'INICH. Our attempts to find a felicitous gloss sey- or tzey- have turned out unsuccessful. In any case, a sign that is found in combination with two or three syllables is likely to be a syllable, too.

Importantly, the same sign appears as part of an enigmatic title on Copan Altar U, X-ta-no-ma (Figure 9c). This context clearly shows that Diego de Landa’s ma is an integral part of the glyph’s graphic design because the number of syllables in Mayan lexical words is restricted to one or two. The sign behaves as a syllable in the context under discussion, too. The context strongly suggests that it is a Ca syllable because -no-ma, -n-oˀm , is the composite suffix of agentive nouns derived from CVC transitive verb roots, whereas long vowels are banned in non-final syllables (Lacadena and Davletshin, 2013: 16; cf. Kaufman and Norman, 1984: 86). Other agentive nouns of this type are known: pa-sa-no-ma WAY-ya, pasnoˀm way, “opener of holes” (Copan Stela A, D10-11), ma-ka-no-ma WAY-ya, maknoˀm way, “closer of holes” (Copan Stela A, D11-12), and yu-ku-no-ma-CH'EN-na, yuknoˀm cheˀn , “shaker of cities” (Dos Pilas Hieroglyphic Stairway 4, Step III, H2-I1) cf. *mak- “(t.v.) to close, cover up”, *pas-“(t.v.) to open, unearth, dig up”, and *yuhk- “(t.v.) to shake”. For the sign in question, a syllabic value p'a would make sense in both contexts: p'a-ye-la CHAN-na-YOP-ˀAT, p'ayeˀl chan y opˀaat , “(The rain god) Yopˀaat is swearing in the sky’, cf. *p'aj- “(t.v.) to swear, curse”, and p'a-ta-no-ma, p'atnoˀm , “one who leaves (something) behind”, cf. *p'at- “(t.v.) to leave behind”. Recently, one of the authors (Davletshin, 2020) has revisited the evidence for the ejective bilabial stops p’ in Hieroglyphic Mayan. Other examples of the medial -j- that gives -y- in particular morphophonetic contexts are known in hieroglyphic texts: siyaj “he/she was born” from the root sij- “to be born”, and tayal “shining”, from the root *taj- “to shine”.

It goes without saying that personal names and titles possess loose semantic control so the suggested interpretations and the proposed reading value p'a for this sign are uncertain. Intriguingly, the origin of the possible syllable p'a? might be related to the word *p'ah “bird louse” acrophonically, perhaps, clarifying the iconic resemblance of the sign to the se syllable, possibly derived from *ses “bird louse”. It is likely that the sign under discussion p'a? and the problematic tze? syllable from the Dresden Codex are identical, in particular, taking into account the fact all composite syllabic signs are abbreviated in the Dresden Codex (see also comments on the graphic development of tze and tzo above). In addition, it is worth noting that the shared graphic design in the signs CHUWEN, WAˀ, ˀUH, cha, se and p'a? might indicate shared visual properties of the objects which the signs in question depict.

Conclusion

To sum up, recurrent graphic differences in various glyphic contexts imply that what has been considered one sign are, in fact, two distinct signs similar in shape that have two different reading values tze and tzo. Both are attested in combinations with other syllabic signs. The composite sign with the central TAL-like element co-occurs with the syllables lo and mo; its plausible reading value is tzo. The composite sign with the central ko-like element tends to be associated with the syllables le and he; its plausible reading value is tze. One lexical entry, tzol- “to count, put in order”, supports the identification of the former; another, letz- “to go up” supports our interpretation of the latter. In Late Classic inscriptions from Northern Yucatan, both signs undergo the same graphic development, in which the upper and lower elements are eliminated but the central elements are preserved.

Diego de Landa’s <c> could potentially be interpreted as either se or tze based on its representation in his manuscript, but one Classic context, viz. se “causative suffix”, clearly shows that the reading value of the sign is se. Another sign in the Dresden Codex could be interpreted as tze. However, this interpretation is restricted to one questionable context and is thus problematic. Importantly, proof for the initial consonant s for Diego de Landa’s <c> occurs in only one secure context of Classic Period, namely, the causative derivation ˀu-t'ab'se “he/she made it lifted”. Nonetheless, the reading se is considered well established and widely accepted among epigraphers. In this regard, the Classic syllables tze and tzo both show the same level of validity as the se syllable, each one depending on only one reliable context, letze “he/she ascended/went up” and ˀu-tzolow “he/she counts/puts in order (them)”, respectively.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)