1. INTRODUCTION

On October 30, 2022, the left-wing former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (hereafter Lula da Silva), standing for the Workers’ Party (PT, Partido dos Trabalhadores), won the presidential race and will govern Brazil for a third time from 2023 to 2026. To win the election, Lula da Silva built a broad alliance that included parties from the center and center-right. His victory margin was the tightest in the history of Brazil’s presidential elections after democracy was restored in 1984. By only 2 million votes, in a country with 156 million voters, Lula da Silva beat the extremist Jair Bolsonaro, who was trying to win reelection after four years of a far-right administration.

In January 2023, when Lula da Silva starts his third term, his biggest challenges will be: 1) To unify a politically divided country and avoid the continuation of political polarization in Brazil, which is on the verge of affecting Brazilian democracy; 2) to mitigate the social inequality1 that sharply increased because of the 2015-2016 recession, the poor economic performance observed since 20172, and the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on the economy; 3) to reduce inflation and keep it under control, as well as to ensure the conditions necessary for sustainable economic growth; 4) to manage fiscal and monetary policies that aim to stimulate economic activity while balancing the fiscal deficit and stabilizing the public debt; and 5) to address environmental issues, such as the deforestation in the Amazon.

This article has two main objectives. The first is to analyze the political economy of the 2019-2022 Bolsonaro government. We will argue that there has been no clear economic policy guidance driving the policymaking of Bolsonaro’s Brazilian Economic Authorities. Our argument is that the Minister of Economics, Paulo Guedes, took ‘dispersed’ and ‘reactive’ economic measures. By ‘dispersed’ we mean that there was no consistent line or goal driving his economic actions, and by ‘reactive’ we mean that most of his actions were simply responses to Bolsonaro’s wishes, which were focused on improving his popularity and electoral chances. Therefore, our second objective is to present Lula da Silva’s main economic challenges in his third term. Accordingly, we also speculate about possible economic policy proposals that the Lula da Silva government may implement to address those challenges.

In addition to this Introduction, this article includes three further sections. Section two displays and discusses the ‘dispersed’ and ‘reactive’ economic agenda and the main economic outcomes of the Bolsonaro government. Section three presents what we consider to be the main economic challenges that Lula da Silva will face. This section also discusses some economic policy proposals that we believe his government should implement to mitigate and/or eliminate the main economic and social problems in Brazil. Finally, section four summarizes our findings and provides our conclusions.

2. THE ‘DISPERSED’ AND ‘REACTIVE’ ECONOMIC AGENDA AND THE POOR ECONOMIC OUTCOME OF THE BOLSONARO GOVERNMENT

To understand the economic agenda that Bolsonaro proposed in his 2018 presidential election campaign, we need to examine the events since 2015. It was then that the president Dilma Rousseff entered the impeachment process that resulted in her being removed from office in 2016. The causes leading to this impeachment process were not straightforward.

Brazil passed through three different sources of instability that fed into the narrative affecting President Rousseff. The first was a huge corruption scandal involving several political parties, but especially Rousseff’s PT; the second was a strong economic recession; and the third was a fiscal crisis (more specifically, the first fiscal deficit since the introduction of the ‘Fiscal Responsibility Law’ in 2000 occurred in 2014). The main consequence of the fiscal imbalance was that the gross public debt increased from 51.5% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2013 to 65.5% in 2015.

Although none of these problems caused any of the others, Brazilian people generally associated them as a causal chain. The popular idea was that corruption involving public resources had created a fiscal crisis, and this, in turn, took the country into recession. In the view of the layman, corruption within the Brazilian State was responsible for the fiscal imbalance that created the economic crisis that caused unemployment to rise from 7.4% in 2014 to 11% in 2016.

If the State was seen as the main cause of the economic issues disturbing Brazil, the solution could only be a liberal agenda that would downsize the State. It did not matter that this interpretation was mistaken. It was the convention that formed the bedrock underpinning the commonsense mindset in Brazil.

Therefore, as soon as Michel Temer, who substituted for Rousseff during her period of official suspension when the Senate considered her case, took up her position in the Cabinet in August 2016, he began adopting liberal reforms to seek both structural diminution of the State and the de-regulation of the markets. By December 2016, the Temer government had already passed a constitutional amendment that put a cap on how much the public budget could grow from one year to another. Called the ‘New Fiscal Regime’ and intended to remain in place from 2016 to 2036, budget expansion became limited by the previous year variation of the target consumer price index in Brazil. Consequently, for 20 years the overall federal budget in Brazil would have no real increase. A specific expenditure could only grow in real terms via a reduction in other spending.

De-regulation was the other way chosen to reduce State economic intervention. The most substantial reform was the market labor reform that happened at the beginning of 2017. This reform was typically liberal in economic terms as it reduced the power of workers’ unions and gave power to individual labor negotiations. Coincidently, informal labor hiring, which is the hiring of workers employed without any labor or social security rights, has since 2017 increased faster than formal recruitment. In 2022, the level of informal employment peaked and has approached formal employment. However, Temer’s liberal reforms went no further because he too was caught in a corruption scandal in May 2017, and from that moment until 2018 his government only focused on avoiding his impeachment.

It was in this context that Bolsonaro started his bid to become president of Brazil. Bolsonaro was a former army officer who was forced to retire in 1988 after facing charges of insubordination. In 1990 he was first elected a federal deputy, in which role he continued until 2018. His particular characteristic has always been his far-right rhetoric, giving speeches filled with hatred for minorities. In the wave of worldwide far-right electoral success that has risen since 2010, Bolsonaro saw the opportunity to stand in the Brazilian presidential election of 2018.

Being an experienced politician, Bolsonaro noticed that in 2018 Brazilians still believed in the maxim ‘the more liberalism, the better’ and he thus proposed a full-fledged liberal agenda for his government. To build confidence that his proposals for a liberal economic agenda were genuine, during his campaign Bolsonaro invited Guedes, a famous liberal Brazil economist who gained his PhD at the University of Chicago, to be his Minister of Economics. Guedes sponsored proposals for implementing a wide liberal agenda in Brazil aimed to reduce the size of the State. These proposals, incidentally, were only a repackaging of the old liberal staples of downsizing governmental roles in the economy, like the privatization of state-owned enterprises, market de-regulation, fiscal consolidation and prone-to-competition regulatory marks. He believed that these were the only way to restore economic growth.

Bolsonaro won the 2018 presidential election in the second round. Thus, Brazil joined the ranks of far-right nations whose numbers had been increasing across the world since the mid-2010s. On his inauguration, in January 2019, Bolsonaro reaffirmed his intentions to implement a radical liberal agenda. Taking advantage of the popularity of the Bolsonaro government, Guedes had the chance to present his policies, based on the ‘expansionary fiscal contraction’ or ‘expansionary austerity’3, to make the Brazilian economy liberal.

At the beginning of 2019, Minister Guedes advanced a social security reform bill. His proposal was bold: He even intended to change the Brazilian public social security system’s pension scheme from the ‘solidarity’ to the ‘capitalization’ type. However, Guedes’ political weakness was exposed during the discussions with the National Congress about the bill. He lost the negotiations with the National Congress and his proposal was deeply changed by congress’ representatives. At the end of 2019, the social security reform was approved, but not in the form Guedes wished for. The National Congress, which was responsible for the approval of the bill, decided to re-adopt the social security reform proposal made by the Temer government and it was this bill that was passed.

Guedes did not win the battle for his proposal, but he won the war for social security reform. He did not see his proposal ratified by the National Congress, but he did at least get social security reform accepted. This reform was important because social security in Brazil is the single greatest federal expenditure. For instance, for the fiscal year of 2023, the federal public budget allocated 45% of its expenditure to the social security system, equivalent to approximately 8% of GDP. The reduction of social security expenditure is a reduction of State economic action, an agenda Guedes backed.

The other bill that Guedes approved was called the ‘Economic Freedom Law’. This law referred to reducing the bureaucracy necessary to enable business operation in Brazil. The intention of the bill was to reduce the regulations with which compliance was necessary to open and close businesses in Brazil. It was a kind of law aimed at reducing transaction cost. Although this law improved the operations of business in Brazil, it did not require any deep change in State affairs. It was mostly related to the number of steps and paperwork involved in doing business.

After these two bills were passed, the importance of Guedes’ liberal agenda, as well as his position as Minister, vanished. At most, we can say that Guedes acted to approve some regulatory frameworks, like those affecting the sewerage system and railways. Although important to bring in private investments, these regulatory changes were neither novel to Brazil, nor seen as a Chicago University-type liberal agenda. In both left- and -right-wing governments before Bolsonaro, this sort of regulation was proposed and approved.

Moreover, the Central Bank of Brazil (CBB) gained its de jure autonomy. Although this can also be seen as a liberal reform, the only significant difference this law made was turning the de facto autonomy of the CBB into a de jure autonomy. The CBB was already autonomous in all but law since the 1990s. Although the Bolsonaro administration was an important player in passing the bill that updated the legal status of the CBB, it was not Guedes’ victory. Rather, the speaker of the House of Representatives, Rodrigo Maia, and the Chair of the CBB, Roberto Campos Neto, were the figures behind the CBB autonomy law.

Finally, in 2022, Guedes was able to enact the first major privatization by the Bolsonaro government. He had sold some subsidiaries of Petrobras, the state-owned oil company, but he was unable to promote his ultraliberal privatization agenda. In 2022 he managed to sell the state-owned company Eletrobras, a major player in the energy sector that acts in all segments of the energy market. Curiously, Eletrobras had had surpluses since 2017 and thus it was a great dividend payer to the federal government. Nevertheless, Guedes made every possible effort to sell the company due to his ideological commitment to the notion that good companies are private ones.

All in all, despite being in office for the whole Bolsonaro government, Guedes was unable to enact his liberal agenda. Regardless of how one feels about this type of agenda or Guedes’ time in office, one must acknowledge that his legacy as the leader of the liberal revolution in Brazil is essentially null. In his time as Minister of Economics, all Guedes did was pursue, and justify to the financial market, the various economic measures that Bolsonaro demanded to increase the popularity of his government and improve his chances in the electoral contest of 2022.

In the wake of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, Bolsonaro decided on a risky strategy. Threatened by the negative economic consequences of the pandemic, which could be detrimental to his political popularity, and betting that a recessive economy would be worse for his popularity than mortality figures, Bolsonaro chose to position himself against lockdowns, attacking them in intemperate terms. He gambled on achieving herd immunity and minimized the efforts of public health workers that were directed towards avoiding the spread of COVID-19. At the end of 2020, he even delayed the acquisition of vaccines. However, as Brazil climbed the ranks of countries where COVID-19 was deadliest, Bolsonaro’s popularity decreased.

Brazil declared COVID-19 a pandemic in March 2020. In April 2020, the CBB quickly undertook measures to guarantee financial stability; it was quite successful in avoiding a financial crash in the country (Carmo and Terra, 2023). However, following Bolsonaro’s minimization of the pandemic, Guedes undertook no fiscal policy action to help people or businesses in Brazil4. On the contrary, he not only denied the impact of COVID-19, but also believed that the continuation of liberal reforms and a huge fiscal adjustment were the appropriate responses to tackle the COVID-19 crisis.

The lack of countermeasures addressing the gravest social, economic and health crises in a century was such that in May 2020, two months after the pandemic started, the National Congress and the Supreme Court of Justice forced the Bolsonaro government to change the short-term course of their economic policy. Thus, the National Congress passed a constitutional amendment to create a countercyclical fiscal policy. This National Congress decree established several fiscal measures, whose cost equaled almost 10% of GDP and caused the gross public debt to grow from 77% to 90% of GDP (Ipeadata, 2022).

In this decree, suggestively called the ‘War Budget’ constitutional amendment, the four main fiscal measures to counteract the effects of the pandemic were: 1) an emergency income benefit given to low-middle-class and poor Brazilians; 2) the provision of resources to states and municipalities, as these were the front line confronting COVID-19 (in Brazilian federalism, the Union offers monetary resources to the public healthcare system while the physical health infrastructure and workforce is funded by states and municipalities); 3) assistance to firms to help them afford their payroll and furnishing them with collateral so that they could borrow working capital; and; and 4) the expansion of the resources available to the health ministry. The decree also allowed the CBB to buy public and private securities in their secondary markets (although authorized, the CBB did not make any such purchases).

The impact of these fiscal measures softened the Brazilian recession caused by the COVID-19 crisis. In 2020, the Brazilian GDP dropped 3.9%, much less than the initial forecasts of a recession of around 9% (IMF, 2020). The unemployment rate, as expected, increased from 11.9% in 2019 to 13.5% in 2020 (Ipeadata, 2022).

As previously explained, the Temer administration had passed a law that set a cap on most federal primary spending. The ‘War Budget’ decree was the first time that this spending cap was waived to permit more expenditure than the maximum limit. The waiver was vital, as without it Brazil would have been unable to offer any kind of fiscal assistance to its population in 2020. However, the decree was due to lapse on December 31, 2020, as if the pandemic would finish tidily with the calendar year.

In 2021, not only had the pandemic not run its course (its worst and deadliest wave came in the first few months of 2021), but nor had the Government done anything to implement economic policies that would arrest the negative impacts of COVID-19 in 2021. Bolsonaro’s popularity fell precipitously. Facing the dual threat of impeachment and plummeting popular support, the President decided to empower the National Congress to allocate a significant portion of the federal budget. In exchange, Bolsonaro need not fear deposition by the National Congress and, moreover, could ask the National Congress for approval for populist measures aimed at improving his image. It was in this context that Guedes was sidelined. His mission became justifying the casuistic economic measures that his chief, Bolsonaro, demanded.

The first of these measures came in March 2021 and required another constitutional amendment. Because Temer’s 2016 spending cap bill was made by constitutional amendment, waivers of the spending cap would only be valid legally if the appropriate changes were made to the Federal Constitution.

By the way, these measures were called the ‘Emergency Constitutional Amendment’. It was a constitutional amendment that proposed two lines of action. First, it created triggers so that if federal spending surpassed the cap by a pre-arranged amount, the spending would return to the level of the cap. Second, it maintained the emergency income benefit, but at a much smaller monthly payment level.

While the amount spent by the federal government on emergency income benefits in 2020 equaled R$ 293 billion (almost USD 56 billion at the average exchange rate of 2020)5, in 2021, the deadliest year of the pandemic, it totaled only R$ 60 billion (around USD11.1 billion at the average exchange rate of 2021) [Tesouro Nacional, 2022]. The expenditure required of the emergency income benefit, the ‘Emergency Constitutional Amendment’ stated, would neither count for the spending cap fiscal rule, nor would they be considered in the primary balance of the federal government. They existed outside the fiscal rules -an arrangement to which Guedes gave his blessing. The only limit on the emergency income benefit was its sown budget cap, R$ 44 billion (USD 8.2 billion at the average exchange rate of 2021) for 2021. This amount was far less than was needed given COVID’s prevalence in 2021 and the severity of the third wave that happened that year. But no effort was made by the Government to improve the allocation of resources given to this public policy against the effects of the pandemic. Instead, the true effort was made by the National Congress.

Given his denial of the pandemic and the terrible number of deaths in Brazil, Bolsonaro’s popularity continued to decline, despite some good figures emerging from the economy in 2021. The GDP grew 4.6%, but statistics played a role in this impressive number: The base of calculus was a too negative one, that is, in 2020 GDP growth rate was -3.9%. Although GDP growth of 4.6% was quantitatively good, the quality of life in Brazil fell quickly. The reduction in the budget of the emergency income benefit increased poverty and misery. Unemployment improved in 2021 and ended at around 11.1%, against 13.5% in 2020. However, it was primarily informal employment, whose income is volatile, that increased. Inflation finished 2021 at 10% (Ipeadata, 2022). With the deterioration of labor conditions plus inflation, even though unemployment reduced, the average income for labor fell almost 15% from the third quarter of 2020 to the third quarter of 2021, reaching its lowest level since 2012 (IBGE, 2022).

As the 2022 elections drew near, Brazil saw two new fiscal amendments made to the country’s Constitution in the months between November 2021 and June 2022. In December 2021 a constitutional amendment was made to insert two changes into the spending cap fiscal rule. The first altered the time period of the consumer price index that stipulates the variation in the spending cap from one year to the next one. The reason for this change was that inflation in Brazil reached 10%. With higher inflation affecting the formulation of the budget, more spending could occur in 2022, an electoral year. Thus, the reason for this change was strictly electoral.

This change was endorsed by Guedes, but the National Congress led the proposal. Congressional representatives sought more funds to manage in the budget, as Bolsonaro had given them control over a bigger proportion of federal resources in order to avoid impeachment and gain political space to approve his legislative agenda. This bill provided the Government with more funds with which to fight the presidential election of 2022. The change in the formula for computing the next year spending cap added R$ 65 billion (almost USD 11.5 billion at the December 2021 exchange rate) to the finances available under the cap. It meant a rise of almost 4% in relation to the budget projected using the former method.

The other constitutional change made in the December 2021 amendment was the limit set on the payments of indemnities in lawsuits lost by the federal government. An indemnity is an amount owed to those who won legal actions they have taken against the State. In 2022, the volume of indemnities payable by the federal government was very high, for various reasons, although they had been forecast in the annual budget law. But if these indemnities were paid, they would occupy the space available under the spending cap fiscal rule, thus limiting the amount of money that the Government and the National Congress could use in an electoral year.

The solution came through another constitutional amendment. That amendment created a ceiling for the annual payment of indemnities by the federal government. This in turn pushed up the limit capping federal primary spending by R$ 43.5 billion (almost USD 7.7 billion at the December 2021 exchange rate); this was an increase of 2.7% in the spending cap (Tesouro Nacional, 2022). In total, the two changes made in the constitutional amendments of December 2021 raised the limit of federal primary expenditures by almost 7%.

All these spending cap dodges had Guedes’ support. That support manifested not so much in making the changes politically viable -the National Congress handled that- but in explaining and justifying to the market, mostly to financial markets, why a government that was supposedly liberal was creating so many reasons to break the Brazil’s fiscal policy spending cap. The problem was that these circumventions of the fiscal rule were neither directed toward creating a plan for boosting investment nor accompanied by any proposal for structural change in the spending cap fiscal rule, which was clearly dysfunctional, as shown by all the assaults it suffered. They were pure and simple attacks on the spending ceiling, pursued to liberate funds for the short-term political plans of both president Bolsonaro and Congressional representatives.

Notwithstanding these two constitutional changes in 2021 and the whole range of electoral-prospect-enhancing federal expenditures that they enabled, in July 2022 another constitutional amendment passed. From the start of 2022, the polls showed that former president Lula da Silva led the field for the presidential election. Bolsonaro, seeking reelection, made another fiscal bet. Congress’ representatives (the majority of them also hoping for reelection in 2022) and Bolsonaro enacted the third constitutional amendment in less than a year.

This time, the bill had two aims. The first targeted the reduction of energy (mainly oil) prices. As was the case across the world, oil prices caused energy prices to rise sharply in Brazil, in turn causing consumer prices to grow as well. Something that particularly aggravated the impact of the rising oil price on Brazilian consumer costs was the policy of international price parity adopted from 2017 by the oil-state-controlled company Petrobras, which sets the prices in Brazil’s oil market. Every movement of the international price of oil is transmitted to the price that the company sets in the local market. Running behind Lula da Silva in the polls and seeing the Government’s popularity fall short of expectations, Bolsonaro decided to intervene in the prices of electrical energy and fuel. However, he did so not by changing Petrobras’s price policy, but by imposing a reduction in the taxes that states levied on fuel and energy. This tax cut was made by the July 2022 constitutional amendment.

Note that this tax reduction, made by Bolsonaro with strong support in the National Congress, did not concern federal taxes on oil and electrical energy, but rather state taxes. The Brazilian Federal Union thereby defined an upper limit that states could levy on electrical energy and fuel. As this new limit was below the average tax states charged on these items, several states ended up with lower incomes from taxation. Electrical energy and fuel are widely consumed goods, and thus they are states’ key source of public revenues. Nevertheless, this was irrelevant to Bolsonaro and the lawmakers in the National Congress when they proposed, and approved, this constitutional amendment. Nor did it matter to Guedes, whose role was to justify to the financial markets the bill’s importance, regardless of its effects on state finances or the fiscal stance of the public sector.

The second aim of the 2022 constitutional amendment was to increase the benefits available to the Brazilian population. Eyeing the October 2022 general elections, this amendment established that from August to December 2022, poor Brazilians would receive additional funds in their emergency income benefit, which was renamed ‘Brazil Aid’, taxi and truck drivers gained a financial voucher, elderly Brazilians were allowed to use public transport for free, and poor families received a cooking gas voucher.

All these measures were necessary because the Brazilian social fabric had begun to deteriorate quickly as the pandemic continued. However, these measures should not have been implemented only from August 2022; rather, they should have been a continuance of the efforts made in 2020 to mitigate or alleviate the pandemic’s impact. Nor should they have had an end-date of December 2022. Problems do not vanish according to a neat calendar timetable.

Therefore, it may be convincingly argued that the 2022 constitutional amendment was exclusively for the purpose of generating electoral gains for Bolsonaro and lawmakers. The law’s fiscal measures were neither designed nor intended to improve the lives of impoverished Brazilians in a structured or planned way. Rather, their purpose was to garner votes in the October 2022 elections. Initially, Guedes described the constitutional amendment as a ‘kamikaze’ act against the spending cap fiscal rule. Rebuked by Bolsonaro, the Minister then deemed the amendment ‘kindness’.

As always, Guedes was reacting to the populist and election -driven fiscal demands of his chief. Thus, Guedes’ true role from 2020 to 2022 was not to develop medium- and long-term liberal fiscal plans, but to offer excuses to the market for Bolsonaro’s government doing the opposite to what he had promised in the 2018 electoral campaign. Guedes compromised himself as Bolsonaro dismantled fiscal rules in an attempt to win the reelection no matter the fiscal cost and despite the rupture of institutions.

If, in terms of fiscal policy, the mark of the Bolsonaro administration was its terrible use of this crucial economic policy, its involvement in monetary policy was somewhat different. At the beginning of the pandemic, in 2020, the CBB aimed to provide liquidity to the National Financial System and reducing the base interest rate, known as Selic. The CBB was essential for avoiding a financial crash in Brazil during the pandemic. The Bank implemented capital and liquidity assistance measures to ensure financial stability and expand credit supply to consumers and entrepreneurs. Thus, the base interest rate was quickly cut and reached its lowest historical level, 2% per year, in August 2020.

In 2021, although the pandemic continued, the challenge worldwide became inflation. The CBB anticipated its reaction to the global inflationary shock that followed the pandemic, and, in March 2021, it started raising Selic, a movement that continued until August 2022. The Selic rate increased from 2% to 13.75% (at the end of 2022). This huge increase created an enormous Selic positive differential in relation to advanced and emergent economies’ average interest rates and helped prevent inflationary depreciations of the Brazilian Real.

It was in this context of anticipated response to inflationary pressures that, in February 2022, the Brazilian economy was met with the Russian war against Ukraine. As occurred in other countries worldwide, the war caused more inflation because of rising commodities prices, especially oil-based energy. To respond to this new inflationary pressure, the CBB kept in place the constrictive policy it had emplaced in March 2021.

The high policy rate decelerated the growth of the Brazilian economy from 2021 to 2022. However, the spread of vaccination made possible the recovery of the service sector, which is the most important supply sector in the Brazilian economy, accounting for almost 69% of the country’s GDP (IBGE, 2022). Accordingly, as services are labor-intensive, unemployment sharply declined in 2022, from 11.1% in the last quarter of 2021 to 8.7% in the third quarter of 2022 (IBGE, 2022).

Yet let us not mistake the nature of this sharp fall in unemployment: Although unemployment fell, this movement was a result of informal employment movement. The increase in commodity prices also helped Brazil, one of the most significant commodity exporters in the world. Together, the recovery of services plus the help given by high commodity prices enabled the Brazilian economy to grow around 3% in 2022, a comparatively good outcome considering that the Government made no fiscal effort to push the economy up and the CBB sharply raised the policy rate to confront inflation.

Let us sum up the data regarding the Bolsonaro government. At the time of writing this article (November 2022), if the CBB’s (2022b) projections for 2022 are confirmed, meaning that the main economic indicators of Bolsonaro government (2019-2022) will be as follows: 1) 1.2% per year average GDP growth; 2) 6.2% annual average consumer inflation (so that in all years, inflation will be higher than the target); and 3) an average unemployment rate of 11.8% per year6. Thus, the Bolsonaro government’s promises were not fulfilled. The Brazilian economy has not grown sustainably and finished 2022 at approximately the same level as it was at the beginning of the 2010s. High unemployment since 2015 was not corrected; the better employment level in 2022 was due to informal employment, indicating that people are fighting for survival. The portion of the population below the poverty line increased markedly during Bolsonaro’s term (Neri, 2022).

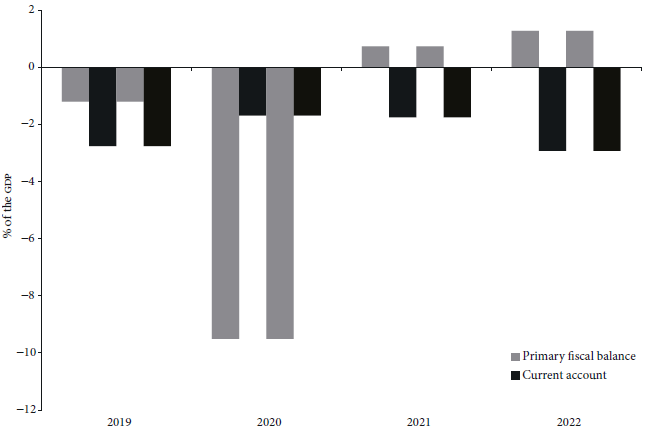

Figures 1 to 3 below summarize the main economic indicators of Bolsonaro’s government. Figure 1 displays the main short-term aggregate indicators, namely consumer price index, GDP growth and the Selic, unemployment and Forex rates. These indicators show how GDP growth oscillated in the period, the high unemployment rate, the decrease in the Selic rate in 2019 and 2020 and its fast elevation in 2021 and 2022 and the constant depreciated exchange rate. They also report that the consumer price index was always above 4%. In 2021 it reached 10%, accumulating almost 27% of inflation from 2019 to 2022.

Notes: 1) Average Forex rate in R$; all other data in %; and 2) estimated GDP growth for 2022.

Source: Ipeadata (2022) and CBB (2022a).

Figure 1 Main macreconomic indicators, 2019-2022 (in % and R$)

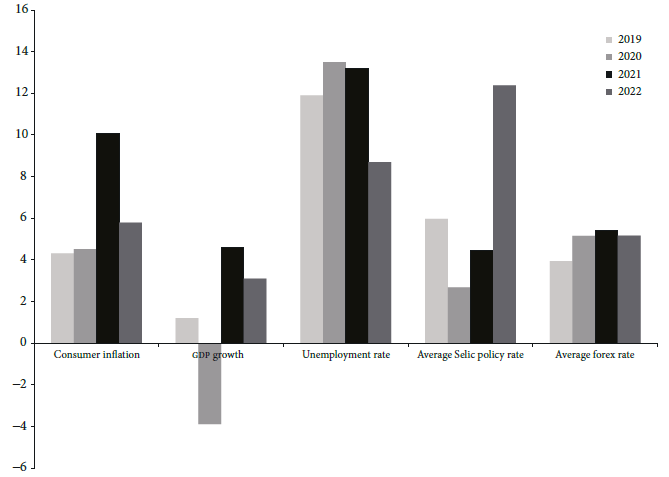

In terms of fiscal and external balances, Figure 2 reports the primary fiscal and current accounts balances of Brazil under Bolsonaro’s administration. Brazil had deficits in its current account during the whole period, even having the world seen high commodity prices, which are the main export product of Brazil. The primary fiscal balance improved from 2019 to 2022. From the greatest fiscal deficit ever in 2020, the country achieved fiscal surpluses in 2021 and 2022, which were outcomes of better economic conditions in these two years. In particular, the good economic performance of 2021 resulted from the fiscal expansion of 2020 which aimed to confront the negative economic impacts of COVID-19.

Finally, Figure 3 reports the stock of the Brazilian gross public debt in relation to the country’s GDP. After peaking almost 88.8% of the GDP in 2020 as an outcome of the policies made to confront the COVID-19 economic crisis, the level of the Brazilian public debt fell fast. In 2022, the debt equaled 73.5% of GDP. Therefore, the debt fell around 15 percentage points in 2 years, a quick decrease. The reasons behind this noticeable diminishment of the debt are the improvement of the economic performance in relation to the expected GDP growth in 2022 and the inflation accumulated in the period.

To conclude this section, one can say that in economic policy terms the CBB has been too conservative since 2021, but at least it was not as lax as the ‘dispersed’ and ‘reactive’ regime Guedes led in the Ministry of Economics. Moreover, while the CBB was correctly committed to combatting inflation, the fiscal policy did nothing to bolster the economy. It was an idle fiscal policy as regards Brazilian development because it was fixated on the 2022 Brazilian elections. It was in this context that the 2022 elections occurred, and Lula da Silva triumphed. What are the challenges bequeathed to him by the Bolsonaro administration?

3. THE CHALLENGES AWAITING LULA DA SILVA’S THIRD GOVERNMENT

Already, in advance of his inauguration on January 1, 2023, Lula da Silva was struggling to deal with the economic inheritance the Bolsonaro administration bequeathed him. Brazil’s fiscal condition will not be easy to manage because Bolsonaro has given the National Congress significant control over the 2023 budget. How can the Lula da Silva government implement his promises if the budget is already committed to resource allocations made by the former government and the National Congress?

Lula da Silva’s third government has been attempting (as of the time of writing) to negotiate with the National Congress a new fiscal waiver to the spending cap fiscal rule. This waiver would furnish funds to allow the future government to implement some of the promises Lula da Silva made during his campaign, such as extending the income distribution program ‘Brazil Aid’ throughout 2023 and adding a bonus per child to each recipient family, promoting real advancement of the minimum wage, restoring social programs, and readjusting salaries for civil servants. The Brazilian population has just democratically decided that they want these promises to be delivered, but Bolsonaro’s government has left the Lula da Silva government without room to maneuver under the spending cap fiscal rule.

All that being said, the greatest challenge for Lula da Silva’s third term will be combining fiscal relief that confronts Brazil’s social deterioration since 2022 with reformation of the spending cap fiscal rule. Brazil needs a new fiscal rule as the spending ceiling introduced by Temer in 2016 was broken from 2020 to 2022. However, the new Government cannot wait for a new fiscal rule to be setup to help the suffering people of Brazil. The alignment of these two needs -the short-term, immediate inclusion of poor people in the federal budget and the medium-term arrangements for a new fiscal rule- will be key to the fiscal success of the Lula da Silva government. It is also its most urgent task.

This alignment faces an underlying political challenge: The National Congress has never had so much power over the federal budget. How will Lula da Silva manage to reduce it? The current President, a charismatic leader who is particularly skilled as a negotiator and conciliator, has suggested that this negotiation might take some time to conclude. The task is made harder by the fact that the next National Congress legislature (2023-2026) is mostly composed of non-aligned lawmakers. This means that the Congressional representatives are not party-led either in support or opposition to the government; they are swing voters that do not follow any set or predestined behavior. Their decisions are based on their electoral and political interests. In Brazil, these representatives are called ‘centrão’, which means that they are inhabitants of the large political center. Lula da Silva will have to use much of his political capital to convince the ‘centrão’ to abandon the power they gained over the budget.

A new fiscal policy design is also needed because another challenge confronting Lula da Silva is the expansion of public investment. Public investment influences private investment not only because it builds infrastructure on which private agents build their products, but also because of its multiplier effects. However, the spending cap fiscal rule has caused public investment to fall to its lowest level ever. It has not even been able to cover the depreciation of public patrimony. This is a challenge in which public banks can help, especially the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES, Banco Nacional de Desenvolvimento Econômico e Social).

Considering that federal expenditures must increase to fulfil campaign promises and to fund public investment, a new fiscal rule for federal expenditures must be planned. To accompany the changes to the expenditure side of fiscal policy, a tax reform must be made. This is another difficult task that Lula da Silva must undertake. Brazil has one of the most inefficient, costly and regressive tax systems in the world. It is a system that increases production costs, reinforces inequality (because it is mostly charged on products), furnishes exemptions equivalent to more than 2% of GDP, and is very light on wealth and superfluous products, like jet skis, helicopters and yachts. Moreover, profits and dividends are not taxed. It is impossible to dismiss the need for massive tax restructuring and overhaul as a challenge confronting Lula da Silva in his third term.

We have said much about fiscal policy and this policy has two sides. Too much attention has been paid to the expenditure side of public finances in Brazil, although it is important. Public revenues must not remain as neglected as they have been for decades.

In terms of monetary policy, the situation in Brazil is tolerable. Inflation has been high, but it is paired with Brazil’s most important commercial partners. The CBB has anticipated making its policy rate mitigate inflation and the situation is under control. Inflation has gradually gone down and seems to be converging on the target set for 2023 to 2024.

But if monetary policy seems to be under control, credit policy might face certain difficulties. Brazilians got poorer during and after the pandemic: Their real income decreased and they lost their jobs, but no structural help came from the government. As a result, their level of personal indebtedness rose and then peaked in 2022. Default rates also increased. This is a difficult issue to address for both social and economic reasons. Lula da Silva’s government has promised to implement a program to help people deleverage their debts. The program will have fiscal impacts, perhaps substantial ones, because the National Treasury will have to furnish collateral or even assume debt.

Although inflation in Brazil seems to be gradually converging on the inflation target, the country must remain vigilant about the main causes of its recent inflation which are, on the one hand, Forex overshooting, and on the other, Petrobras’s price policy. The first was unavoidable during the pandemic and Brazil’s foreign reserves were a good buffer. Still, the Brazilian Real lost almost 45% of its value in relation to the US Dollar between 2020 and 2021. The country’s external sector has not been problematic in recent years, so now might be the time to gather more foreign reserves, which provide the exchange rate policy with more power to offset Forex volatility and give monetary policy more autonomy in its policy rate.

In turn, the Petrobras price policy started in 2017. The liberal reforms made by the Temer administration changed the structure of the oil market in Brazil, but Petrobras remains the market leader and its price policy continues to set the price for the whole market. To reduce the market opportunity cost, in 2017 Petrobras adopted a new price policy to replicate domestically the international changes in oil prices. When commodity prices spiked in 2021 and the Russian war on Ukraine added higher prices in 2022, the producer and consumer price indexes in Brazil were hit by all the external turbulence. Family spending with transport caused more than 40% of the consumer price variation in 2021 (IBGE, 2022). Changing Petrobras’ price policy without both disarranging the oil market in Brazil and breaking contracts is another challenge that the future government must address.

As mentioned previously -but worth repeating- the mitigation of social problems is an urgent challenge that must be resolved. Under Bolsonaro, starvation, misery and poverty, as well as personal, functional and regional inequalities, increased in Brazil, while the human development and Gini indexes stagnated. Brazil regressed between 2019 and 2022 and Lula da Silva is met with the challenge of not only halting this retrograde movement but also making it possible to improve Brazil’s social indicators.

In terms of long-period structural-institutional changes, which are so important to expanding supply capacity and potential GDP, the Lula da Silva government needs to at least start the following, among other things:

1. Expand industrial and technological policies to coordinate public and private efforts, in order to mitigate the de-industrialization process that has been occurring in Brazil for three decades. These policies will also secure the Brazilian economy a place in the international market, and do so in a context where the country can absorb structural and technological changes occurring in the world economy.

2.Implement trade agreements with other emerging economies, such as Latin American, Asian, and African countries.

3. Invest in research, development and innovation in pursuit of productivity gains. To this end, investments in education are essential.

4. Stimulate a cooperative arrangement between public and private sectors (i.e., public-private partnerships), with the aim of expanding infrastructure projects, such as the transport, water, sewerage, education and health systems.

5. Take advantage of the green economy paradigm to boost the development of technology and increase the Brazilian competitiveness in external markets. This will also be important to alter the energy matrix of Brazil, reducing dependence on oil and enhancing the use of renewable energy sources.

Finally, long-period structural-institutional changes cannot disregard the State’s role in the economy, which must be redefined by rebuilding the coordination mechanisms that were dismantled during the 1990s, and, more recently, from 2015 on. The necessity of recovering the State’s presence in Brazil’s economy was proved in 2020. The State’s intervention, through economic policies implemented by the National Congress to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 on the Brazilian economy, was the only factor that helped to minimize the GDP recession that year. The State, in Lula da Silva’s third presidential term, will have to follow Keynes (2007 [1936], p. 378) and “exercise a […] comprehensive socialization of investment”. In other words, the State should exercise its function as the regulator, coordinator and inducer of economic activity. Only this type of State, unfettered by economic policies intended to limit its power, can create the Welfare State so desperately needed in Brazil.

4. FINAL REMARKS

This article analyzed the political economy agenda and the main economic outcomes of the Bolsonaro government. We defined this agenda as ‘dispersed’ and ‘reactive’: ‘Dispersed’ because it did not assume any consistent strategy directed to promote any structural long-term goal, and ‘reactive’ because Guedes’s role in Bolsonaro’s cabinet was to justify all the changes in the fiscal rules that Bolsonaro’s government made in pursuit of achieving populist and electoral goals.

This article also speculated on what Lula da Silva’s main economic challenges and lines of action are likely to be. The principal immediate challenges and tasks are: 1) Making affordable the social programs that will restore the social condition of Brazil’s impoverished population, as well as boosting public investment without losing sight of the need for new fiscal rules and a modern, progressive and comprehensible tax system; 2) reducing the debt level of the Brazilian families; 3) changing Petrobras’s price policy to reduce its influence over producer and consumer inflation; and 4) accumulating foreign reserves.

In our view, the solutions to these challenges will operate on two fronts. The first requires short-term macroeconomic policies. They will attend to macroeconomic stability, seeking sustainable economic growth, controlled inflation, and fiscal and external equilibria. The second, consisting of long-period structural-institutional changes, will address the structural bottlenecks of the Brazilian economy and will concentrate on technological advancement, social inclusion and environmental issues, as these are vital for Brazil’s economic development in the long term.

To conclude, we know that the future is uncertain. But given that in 2023 Lula da Silva will receive a difficult economic inheritance, he has no alternative but to face the country’s problems by replacing the liberal economic agenda pursued since 2015 with a new economic-social project. Let us hope that, despite the political and institutional obstacles placed in front of Lula da Silva in his third term, he can implement a national project that considers and assists all Brazilians.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)