1. INTRODUCTION

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva won the Brazilian presidential elections by a narrow margin on 30 October, 2022, beating the incumbent and far-right President Bolsonaro. It was a major comeback for Lula and the Partido dos Trabalhadores, PT (Workers’ Party). In 2018, Lula was in prison and ineligible to run; he was convicted in 2017 on false corruption charges. The Brazilian Supreme Court anulled the verdict in late 2019 after leaked messages between the judge and the prosecuting attorneys.

Lula and the PT had faced political setbacks in the past. Mensalão was a political scandal that threatened to overthrow Lula’s government in 2005. A neologism for big monthly allowance, it was a payment to Brazilian legislators to buy their votes for government projects. Mensalão became a symbol of fighting corruption. It was also an attempt to remove PT and its political coalition from power. Despite the mainstream media attacks and the conviction of a few PT leaders, Lula was re-elected in 2006 and Dilma Rousseff was elected in 2010. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) expanded by 4.05% annually between 2002 and 2010.

The great political setback began in 2013, when social unrest emerged for the first time in the PT’s governments. Conservative middle class, previously absent from protests, joined in, increasing pressure on the government. They complained about corruption and the costs of organizing the 2014 football World Cup. As a result, the popularity of President Rousseff plummeted, and right-wing groups with connections to the far right in the United States emerged.

Rousseff won the 2014 elections, despite mounting political and economic problems. In the campaign, she argued against low economic growth and high unemployment. However, she implemented austerity policies during the cyclical downturn that started in the second quarter of 2014 (CODACE, 2020). Austerity and the drop in commodity prices led to a GDP fall of 3.8% in 2015, followed by a 3.6% fall in 2016. The economic crisis and the impact of corruption allegations by the so-called ‘carwash operation’ played a role in the soft coup of 2016.

Vice-president Michel Temer, a right-wing politician, took power, suggesting a series of measures aimed at expanding profitability. The main objective was the reduction of labor costs and fiscal deficits. It included proposals to change the minimum-wage indexation rule, reform the labor law, and launch social-security reforms. Also on sight were other neoliberal measures such as eliminating constitutional spending rules in education and health, boosting both privatization and trade openness. The government succeeded in implementing some of the neoliberal reforms. However, political scandals slashed the chances of traditional right-wing parties winning the 2018 election.

The ‘carwash operation’ started in early 2014, investigating money laundering and corruption in Petrobras by many political parties. Lula became the main defendant, and his imprisonment in 2017 was celebrated as the primary achievement of the carwash operation. Additionally, Lula was also barred from running for the presidency which allowed Bolsonaro to win the 2018 election.

In power, Bolsonaro launched an ultra-right neoliberal agenda, reforming the pension system, privatizing public enterprises, ignoring environmental laws, while attacking minority rights and democracy. Brazil is the second country with the highest number of COVID deaths; the official statistic was close to 690 thousand by middle November 2022, while the number of known infected cases was above thirty-five million. The annual GDP growth rate expanded at 0.6% in the first three years of government, and the expected growth rate was 2.8% in 2022. Furthermore, the inflation rate raised from 3.75% in 2018 to 10.06% in 2021, and the inflation in 2022 was 5.79%. Even considering the problems associated with the pandemic and the Ukraine war, there was a poor economic performance.

Economic issues were the voters’ top concern, being fundamental for Lula’s victory. His political support was based on voters with a monthly income up to two minimum wages. They suffered the worst from the return of neoliberalism and the economic crisis. Lula has organized a large coalition; the vice-president is Geraldo Alckmin, a former member of the Brazilian Social Democratic Party (PSDB, Partido da Social Democracia Brasileira), and the presidential candidate in the 2006 and 2018 elections. The PSDB supported the main neoliberal institutional reforms in the 1990s, becoming the main opposition party when PT was in power. The challenge ahead is how to govern with this large coalition, particularly when the government has to face difficult choices about the management of the economy.

Raising GDP growth is necessary to unite and expand the political coalition and implement the redistributive policy promised during the campaign. Despite Bolsonaro’s defeat, his party is the largest in the lower house of the national congress. Pro-Bolsonaro candidates won important state-level elections such as in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Minas Gerais. Without economic growth, ‘Bolsonarismo’ will remain a political force in the years to come.

The article investigates the economic limits and the perspectives of Lula’s third term in Brazil. We approach these issues employing the profit rate and its determinants. The profit rate is central to the functioning of capitalist firms in various schools of economic thought. The decline in profitability after the 2008 crisis due to falling profit share and terms of trade played a decisive role in the break-up of the political coalition organized by Lula, opening up the possibility for the soft coup in 2016.

The paper is organized as follows. Section two presents the profit rate and its components in the Brazilian economy between 2000 and 2021. Section three explores the economic performance and the contradictions of the first pink tide in Brazil. The measures proposed by Lula in his third term as president are presented and explored in section four. Section 5 discusses the economic perspectives and limits in the long term. Section six concludes.

2. THE PROFIT RATE AND ITS COMPONENTS IN BRAZIL, 2000-2021

The profit rate is a central determinant of expected profitability, playing a fundamental role in the business cycle (Weisskopf, 1979). The rise in the profit rate increases the expected profit rate, which drives up investment, expanding production and employment. The fall in the profit rate reduces the expected profitability, driving down investments and aggregate output. Economic policy may raise investment and capital accumulation in the short term. However, in a context of a falling profit rate, investment and capital accumulation will decline in the medium and long term.

The path of the profit rate depends on three factors related to the types of crises in a capitalist economy, as suggested by Weisskopf (1979). First, the profit squeeze is a decrease in the profit share due to the higher bargaining power of workers. For economic and political reasons, wages can rise faster than labor productivity. Second, the decline in capacity utilization due to a lack of aggregate demand. Third, the fall in potential capital productivity due to the rising organic composition of capital. This phenomenon is usually associated with technical change, capital accumulation and mechanization but also occurs when the price of capital goods rises faster than the GDP deflator and the terms of trade decline in an open economy. Despite its origin, the fall in profit rate results in declining investment and capital accumulation and consequently, lower economic growth.

The profit rate is the ratio between the profits and the capital advanced in production. Weisskopf (1979) proposed a decomposition of the profit rate (r) in the profit share (π) in the level of capacity utilization (u) and the potential capital productivity (ρ). The profit rate is calculated as follows:

where Z is net profit, K is net capital stock, X is net output, and X P is the net potential output. For information on the data, see Marquetti et al. (2023).

The increase or decline in the profit rate has important political consequences in a democratic society. Changes in potential capital productivity occur in the medium and long term, and their influences are associated with institutional changes in capitalist economies. The interplay between the functional income distribution and capacity utilization captured by the Goodwin cycles has important political consequences. Raising/falling capacity utilization expands/reduces workers’ bargaining power with consequences for the profit share and the profit rate. The capitalist will answer politically to a profit squeeze, withdrawing support from the ruling coalition in power. Workers also answer to a falling capacity utilization, rising unemployment and declining bargaining power and wage share by voting against the government in power. The economic conditions are a key ingredient in the votes of workers and capitalists (Fisher, 2018). However, capitalists have higher economic and political power to overturn the democratic system. It is especially true in countries without a democratic tradition, as in the Brazilian case.

Looking at the changes in the three variables over time can help to further understand the trajectory of the PT governments at the beginning of the 21st century, throwing some light when comparing the current economic and social conditions the new government faces to the previous ones. Figure 1 shows Brazil’s profit rate and net investment (I) between 2000 and 2021. The changes in the net profit rate precede the movements in the net investment. The result is consistent with Grazziotin, Fornari, and Marquetti (2021), which shows a Granger causality from profit rate to capital accumulation in the Brazilian economy between 1950 and 2016.

Source: Marquetti et al. (2023).

Figure 1 The net profit rate, r, and net investment, I, Brazil, 2000-2021

Table 1 shows the decomposition of the profit rate and the GDP growth rate by presidential terms between 2002 and 2021. The profit rate was trendless for the period due to slightly increased potential capital productivity. This result reflects the deindustrialization of the Brazilian economy during the period. Deindustrialization is a structural change in which economies move from sectors with lower to higher capital productivity. In the de-mechanization processes, a movement occurs opposite to the one investigated by Marx in his analysis of the falling profit rate. The manufacturing share in value added at current prices declined from 15.27% in 2000 to 11.97% in 2021; it was 14.97% in 2010.

Table 1 The net profit rate decomposition and GDP growth rate by presidential term, Brazil, 2000-2021 (%)

| Period | r | π | u | ρ | GDP |

| 2000-2021 | 0.07 | -0.05 | -0.05 | 0.16 | 2.1 |

| 2002-2006 - Lula 1 | 1.67 | -0.41 | 0.75 | 1.34 | 3.5 |

| 2006-2010 - Lula 2 | 0.59 | -0.94 | 0.31 | 1.22 | 4.6 |

| 2010-2014 - Dilma 1 | -2.73 | -2.29 | -0.97 | 0.52 | 2.3 |

| 2014-2016 - Dilma 2 | -6.74 | -3.84 | -4.16 | 1.26 | -3.4 |

| 2016-2018 -Temer | 5.18 | 1.96 | 1.36 | 1.86 | 1.6 |

| 2018-2021 - Bolsonaro | 4.17 | 6.15 | 1.83 | -3.81 | 0.60 |

Source: Marquetti et al. (2023).

Figure 2 shows the profit rate and its components between 2000 and 2021. The profit rate was trendless during the period, displaying cyclical movements. Despite the fall in the profit share, the profit rate rose between 2002 and 2007, driven by increased capacity utilization and potential capital productivity. Between 2007 and 2015, the profit rate fell due to the decline in profit share and capacity utilization. The profit rate expanded between 2015 and 2021 with the increase in profit share and capacity utilization.

3. FROM PINK TIDE TO LATE NEOLIBERALISM: THE BRAZILIAN ECONOMY IN THE 21ST CENTURY

3.1. The Brazilian pink tide

The positive prospects for Lula’s new administration rely on the approvals of the PT’S governments in the years 2002-2014. The period includes the two Lula terms between 2002 and 2010 and the first Rousseff administration between 2011 and 2014. Economic and political crises affected the second term of Rousseff’s presidency, which resulted in her impeachment in 2016. The whole period comprises the pink tide, the wave of left-wing governments that took office in several Latin American countries around 2000. The pink tide combined income redistribution towards labor, poverty reduction, and higher national autonomy. The investigation of the Brazilian pink tide helps us to better understand the possibilities and limits of the new government.

The inefficacy of neoliberalism in promoting economic growth and maintaining profitability in the 1990s played a role in the victory of the Workers’ Party in 2002. There were two other reasons. First, Lula organized a broad alliance between different social sectors, including the working class and bourgeoisie fractions (Boito Jr. and Saad-Filho, 2016). José Alencar, an industrialist, was the candidate for vice president. Second, Lula signed the ‘Carta ao Povo Brasileiro’, in July 2002, informing the financial sector that the government would maintain some neoliberal economic policies, such as high real interest rates (Silva, 2002a). It reduced the opposition of the financial bourgeoisie to the new government.

In power, the Workers’ Party economic policy was pragmatic and moderate, combining elements of developmentalism and neoliberalism. Political and economic reasons determined which one would be hegemonic. A neoliberal economic policy was predominant in the first two years. The government maintained the inflation target regime and floating exchange rates, committing to fiscal balances through primary surplus targets. Henrique Meirelles, a former international bank executive, was appointed president of the Central Bank. There was a redistribution policy towards the poor, the government unified various conditional cash transfer programs in the Bolsa Familia.

On the political side, relations with the legislative branch depended on a wide political coalition, as usual in Brazil. The large alliance implied political constraints for the government, which did not have the majority in the legislative. The crisis of “Mensalão” in 2005 resulted from the attempt to build political support in the legislative. To overcome the crisis, the government formed a new political alliance with the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB, Partido do Movimento Democrático Brasileiro), the largest party in congress.

Economic changes also occurred in the period, developmentalism became hegemonic, and Guido Mantega replaced finance minister Antonio Palocci Filho. Fiscal policy and income transfer programs gained prominence in expanding demand and output growth. The new minimum wage policy came into force at the end of 2006, linking its rise to previous inflation and GDP growth, enabling the increase of labor share and household consumption. The Program of Economic Acceleration (PAC, Programa de Aceleração do Crescimento), a set of public and private investments, was launched in 2007 under the leadership of Dilma Rousseff, when she was the chief of staff of Presidency.

The demand for commodities expanded and the terms of trade improved in the period. Commodity prices rose 135% between 2002 and 2007 (IMF, 2022), which, associated with a high interest rate, led to an exchange rate appreciation. It allowed to combine real wage increases with inflation control. As a side effect, it led to further deindustrialization and increased political power of the agribusiness.

The economic growth between 2003 and 2007, combined with rising terms of trade, allowed for the simultaneous increase in profit rate and wage share. It was the foundation that sustained social and political stability in the Lula years, solving contradictory interests from different social sectors. As the capacity utilization and the profit rates increased, there was no major contradiction between the interests of workers and capitalists, a movement observed in the first Lula government, as Figure 3 shows. It displays the scatterplot between capacity utilization and wage share between 2000 and 2021. The data presents a Goodwin cycle, establishing a non-linear relationship between capacity utilization and functional income distribution.

Source: Marquetti et al. (2023).

Figure 3 The relationship between capacity utilization (u) and net wage share (1-(), Brazil, 2000-2021

Capitalists and workers shared the economic growth with higher profits, wages, and employment. These were the central tenets of PT success: Economic conditions reduced social class disputes (Marquetti, Hoff, and Miebach, 2020a; Martins and Rugitsky, 2021). The high real interest rate that benefitted the financial elites was accepted by popular sectors, while expanding wage share was not opposed by the capitalists.

The economic landscape changed after the financial meltdown in 2008. Fiscal and monetary expansionary policies to stimulate the demand for manufacturing goods worked to prevent a major economic crisis; GDP growth rate hit 7.5% in 2010. The neoliberal crisis affected the Brazilian economy in the 2010s, as the terms of trade declined, the attempts to maintain a high-level capacity utilization rate resulted in falling profit share and profit rate.

The downturn in world trade and the adoption of quantitative easing by the United States induced a shift of global demand to countries with a growing internal market and an appreciated domestic currency. The strategy adopted by Rousseff’s administration was to stimulate private investment via changes in interest and exchange rates. The approach produced some devaluation of the domestic currency but failed to boost economic growth. There were cost-reducing measures, such as the increase in tax exemptions and subsidies, and the use of public banks to reduce the spread in interest rates.

The government expected that the policies would result in a rise in after-tax profits and higher private investments. Public investment would play a complementary role in restoring growth. Economic growth would provide higher tax revenue, restoring the fiscal balance. In this scenario, the financial sector would have to accept a lower interest rate and competition from public banks.

However, the falling profit rates prevented the recovery of private investment. There are clear limits in the capacity of the government to conciliate the distinct interests of social classes. The policies of minimum wage valorization and high employment were maintained in the context of rising labor costs. High employment reduces the cost of job loss and expands workers’ bargaining power.

The financial sector understood the economic policy as the end of the compromise assumed in the “Letter to the Brazilians”. There was a misconception about neoliberalism by Rousseff’s government. The policies adopted were consistent with an acute rift between financial and productive capitalists. One of the main features of neoliberalism is the merger of productive capital with financial capital under the latter’s leadership.

Furthermore, the social unrest that emerged in 2013 and the lower economic growth intensified the dispute between social classes and reduced the government’s popularity. In 2014, President Rousseff was re-elected by a narrow margin. During the campaign, Rousseff acknowledged the economic problems and proposed gradual adjustments to preserve employment and economic growth. In a neoliberal turn, however, she appointed Joaquim Levy, a Chicago-trained economist, as finance minister to re-approximate the financial bourgeoisie.

An austerity economic policy was implemented. The inflation rate reached 10.6% in 2015 after a huge increase in administrative prices, while investment and GDP fell 14% and 3.8%. At the end of 2015, the government attempted to change course, substituting Joaquim Levy with Nelson Barbosa, who proposed a soft austerity combining higher expenditures and taxes with a social security reform, but it was too late.

In the same period, a political crisis broke out over the Petrobras corruption scandal. Media coverage of the ‘carwashing operation’ harmed the government’s image. As it later became apparent, the operation’s main goal was to prosecute and arrest Lula and demoralize the PT. As economic problems increased, an association emerged in the media between the economic crisis, the PT governments, and corruption. This adverse political climate associated with the rupture of class conciliation established in Lula’s first election, generated the social and political conditions for the impeachment of Rousseff.

The 2015 neoliberal turn and the political effects of the ‘carwash operation’ reduced the political support of the popular sectors, which did not mobilize to defend the PT government. Moreover, the bourgeoisie perceived the neoliberal turn as too mild to reduce the workers’ bargaining power and insufficient to restore profitability. When the political crisis unfolded, the Rousseff government was left alone, becoming easy prey for the political articulations that led to its fall through a soft coup.

3.2. Late neoliberalism

The PMDB, the party of Vice President Michel Temer, launched the document ‘Bridge to the Future’ in October 2015, containing measures to restore profitability by reducing labor costs and implementing fiscal austerity. The proposals required a radical and complete neoliberal turn. The soft coup and the implementation of neoliberal proposals marked the end of the Brazilian pink tide. After 2016, there was a rise in the profit rate as the soft coup produced the expected results from the bourgeoisie’s viewpoint.

The distrust and attacks on the political system continued after the coup. Although the main target of the ‘carwash operation’ was Lula, it transcended the PT, reaching Temer’s government and the political parties in Congress. The fierce defense of capitalist interests and political scandals resulted in low popularity. The demoralization of PT and the political system and the dissatisfaction with the government opened the possibility for a far-right-wing candidate. Lula, however, was the favorite for the 2018 election, even though he was condemned by judge Sergio Moro, who later became Bolsonaro’s Ministry of Justice. Lula was arrested and barred from running after the supreme court rejected his appeal for habeas corpus.

It paved the way for Bolsonaro’s victory and the return of the Brazilian army to the political arena. Bolsonaro’s political support was heterogeneous, including conservative and far-right groups, evangelicals, large segments of the military, agribusiness and commercial entrepreneurs, and neoliberal groups led by the finance minister Paulo Guedes, also a Chicago-trained economist.

Bolsonaro’s government promoted social pension reform and introduced a series of deregulations, including reducing environmental and labor protection standards. The independence of the Central Bank was approved, in addition to regulatory frameworks that facilitated private management in areas such as natural gas and sanitation. The privatization of Eletrobrás and the sale of several Petrobras assets, such as BR Distribuidora and refineries, completed a picture representing the deepening of the late neoliberal project. There was a disorganization of the functioning of the state.

The COVID-19 epidemic had a major impact in Brazil. While late neoliberalism was efficient in reducing the wage share and increasing the profit rate, it ran in contradiction to protect health and income of the workers and poor population. Initially, the Bolsonaro government adhered to herb immunity, refusing to act to reduce the spread of the coronavirus. Several health ministers were appointed without a clear strategy to confront the pandemic.

Political and social pressures led the government to act. In April 2020, the National Congress passed a law on emergency cash transfers to mitigate the social and economic effects of the pandemic, promoting a short-term increase in income and reducing poverty. The approval rate of Bolsonaro expanded during the period of payment in 2020. The main component of income of Brazilian households is labor income. When emergency cash transfer programs ended, there was a rapid increase in poverty due to the high unemployment rate and the decline in real wages. In relation to 2020, the average per capita household income decreased by 6.9% in 2021 (IBGE, 2022). The wage share declined sharply during late neoliberalism, as seen in Figure 3.

The combination of the neoliberal agenda and the pandemic led to a sharp decline in the population’s standard of living. Inflation grew sharply during the second half of 2021, and the Ukraine War further impacted real income and the population’s well-being. The decline in living standards and the dire social situation in the resumption of hunger led conservative politicians to exert pressure on the government. In 2022, a new program, ‘Auxílio Brasil’, which violated the fiscal rules, and the reduction of indirect fuel taxes were implemented to reverse the decline in the government’s popularity. In the third quarter of 2022, there were a short-term deflation and a mild employment recovery.

The measures restored some of Bolsonaro’s popularity but were insufficient to ensure his re-election. Workers and the poor population supported Lula. It seems that there are limits to the decline in real wage and household income in societies with regular elections. For the first time since redemocratisation, the incumbent presidential candidate was defeated in the bid for re-election. The 2% margin of Lula’s victory shows the divisive political environment facing the new government. The following sections present the proposed measures and discuss the perspectives and limits of the new government.

4. PT’S PROPOSED MEASURES

On 27 October 2022, just three days before the second round, Lula launched a new letter, the ‘Carta para o Brasil de Amanhã’ (Letter to the Brazil of Tomorrow) [Silva, 2022b]. The letter presents the main proposals of the new government, summarizing the debates throughout the campaign in 13 priority points. It has a wider focus compared with the ‘2002 Letter to Brazilians’, which was aimed at the financial markets and their ongoing repercussions in the real economy. On 22 December 2022, the Relatório Final (Final Report) produced by the Governmental Transition Office reaffirmed the priority points raised in the Letter to the Brazil of Tomorrow.

The priority points can be summarized in eight economic proposals. The measures can be outlined as:

1. Revision of the cash transfer program, dubbed Bolsa Família, with the distribution of extra money depending on the number of children.

2. Provide real gains to minimum-wage receivers and retired citizens.

3. Renegotiation of the debt of citizens in economic difficulties and provision of credit access to the highly indebted population.

4. Income tax exemptions to citizens receiving up to 5,000.00 reals monthly accompanied by a tax reform.

5. Stimulate public and private investments in infrastructure.

6. Use of public banks and state companies to increase investment and provision of services.

7. Reindustrialization, modernization of the country, and entry into digital technology.

8. Fight deforestation and target zero carbon dioxide emissions in the provision of electricity, stimulating sustainable agriculture, mining and quarrying.

Both documents emphasize the necessity for a rapid recovery of state capabilities of planning, execution, and implementation of public policies. The structure and organization of the state suffered in several dimensions under Bolsonaro’s government (Lotta and Silveira, 2021). There was the dismantling of public policies in education and health, restriction of social participation, weakening of social control mechanisms, and obstruction of access to individual, social, and economic rights. The Final Report points to the need to revise and plan several actions to foster state capabilities through reorganizing ministries and revoking several instructions and decrees from the former government.

There is also a sense of urgency concerning Brazil’s repositioning in the international community and its forums, recovering some of the soft power lost in recent years. In this respect, the proposals aimed to restore the Brazilian influence in forums like mercosul (Mercado Comum do Sul), and brics (Brasil, Rusia, India, China and South Africa), as well as in other international institutions associated with the United Nations.

It also aims to implement a new environmental policy to improve the image and help access international funds to preserve the Amazon Forest. International funds are available to fight climate change and Brazil can benefit from that. In addition, the international position can reduce the internal political opposition, helping alleviate pressures and promote the needed reforms. The external scenario and how Lula handles the pressures are key to his success.

One of the first measures of the new government was a Proposed Constitutional Amendment (pca), to allow the new government to raise by R$ 145 billion the spending ceiling in the 2023 Budget. The resources are fundamental for the new government to fulfill some commitments assumed in the Letter to the Brazil of Tomorrow, such as the Bolsa Família of R$ 600, with R$150 per child up to six years old; increase in the real minimum wage; rise in resources for education, and public health. The pca also allows expanding federal investments by R$70.4 billion.

These measures arguably have the potential to spur short-term growth with an expansionary fiscal policy. The new government must sustain the mild economic recovery process started with the opportunistic measures adopted by Bolsonaro. The last months of 2022 saw a recovery in employment and growth. The new PT government will have to face a fierce alt-right opposition. In this polarized environment, it is essential to fight rising unemployment to preserve its popularity. The pca opened some fiscal space in the new government’s first year.

5. ECONOMIC PERSPECTIVES

For the new government, expanding aggregate demand and capacity utilization will lead to higher economic growth. In the short term, economic policy will combine fiscal expansion, rising social transfers to low-income families, and increasing the real minimum wage. While it can foster growth and attend to the initial expectations around the new government, there are several risks in the sustainability of a long-term growth trajectory, especially in the case of a fall in the profit rate due to a profit squeeze.

Additionally, there are fiscal limits for expanding public investments. In the second quarter of 2022, federal government revenue reached 32.1% of GDP, and expenditure was 37.2%. Of total expenditures, 24% went to interest payments and 40.9% to the payment of social security and assistance benefits, while investment reached 0.67% (STN, 2022). There is room for easing the tight monetary policy in the short term; the basic interest rate was 13.75%, and the inflation rate in the last 12 months was 5.9%. The real interest rate is running at 7.41% annually.

There will be an increase on bargaining power of workers. A new rule will be proposed to raise minimum wages above inflation. In 2006, the law of minimum wage appreciation was established, correcting it according to the annual inflation and the GDP growth rate of the two previous years. The real minimum wage rose by 82%, the real GDP expanded 50.7% between December 2002 and December 2014. From 2016 to 2018, the minimum wage grew in line with inflation due to the slowdown and decline of GDP. In 2019, the Bolsonaro government eliminated the policy that considered GDP growth as an element to raise minimum wages. With the new government, revising labor laws, expanding workers’ rights and strengthening trade unions is now possible.

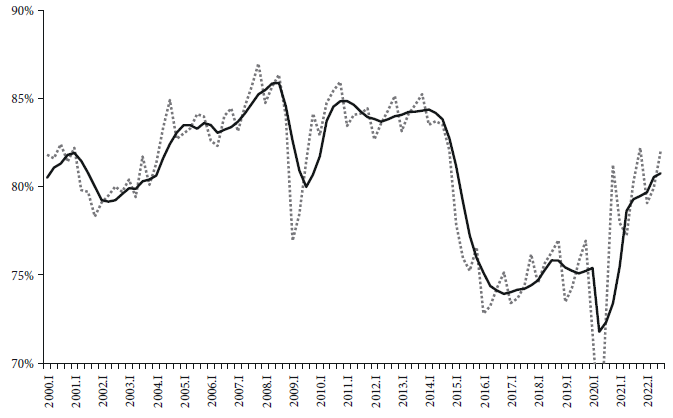

Figure 4 presents the capacity utilization in the Brazilian industry from the first quarter of 2000 to the third quarter of 2022. The dotted line displays quarterly data, and the solid line shows the four-quarter moving average. The industrial capacity utilization in 2022 was similar to the first semester of 2004. This finding is consistent with the data observed for the whole economy and in the Goodwin cycle in Figure 3. From this perspective, the economic situation in 2021 and 2022 is comparable to that of the early 2000s. Thus, a wage-led growth strategy can stimulate output growth in the short term. Despite the decline in the profit share, the profit rate would rise by increasing capacity utilization, a movement analogous to that which occurred in Lula’s first term.

Source: Fundação Getúlio Vargas (2022).

Figure 4 Industrial capacity utilisation, Brazil, 2000.I-2022-III

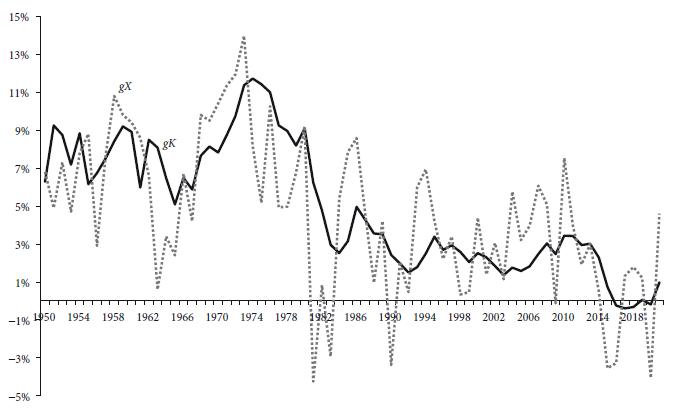

However, higher economic growth in the medium and long term requires greater capital accumulation. In the ‘Letter to the Brazil of Tomorrow’, the references to the expansion of capital accumulation are the stimulus of public and private investment in infrastructure, the use of state enterprises to increase investment, and the reindustrialization of the country. Figure 5 shows that capital accumulation determines GDP growth in the long term. To raise Brazil’s long-term growth to 4% (the average performance during the first two Lula terms), requires expanding capital accumulation by 4% if the capital productivity remains constant.

Source: Marquetti et al. (2023).

Figure 5 Capital accumulation (gK) and GDP growth rate (gX), Brazil, 1950-2021

In the last 70 years, Brazil has gone through two phases in terms of economic growth. First, during developmentalism between 1950 and 1980 the GDP growth rate was above 7% per year. Brazil was one of the most dynamic economies worldwide, the industrial sector fueled growth in a framework of industrialization by import substitution. The erosion of that process began in 1973 with the end of the golden age of capitalism. There was a fall in the profit rate in the Brazilian economy.

Second, during neoliberalism, from 1980 to 2021, the GDP expanded at 2.3% annually, a staggering decline. Neoliberalism can be further divided into four subperiods. First, from 1980 to 1989, when the economy struggled with stagnation and rising inflation, and import substitution industrialization was abandoned. Second, between 1989 and 2002, when neoliberalism was adopted. There were the opening up of the trade and financial accounts, the privatization of public enterprises, the reduction of the state’s role, the control of inflation in 1994 with the Real Plan, and the adoption of the inflation targeting regime in 1999. Third, between 2003 and 2014, Brazil implemented policies that combined developmental and neoliberal elements. The GDP expanded by 3.4% annually, the best economic performance since 1980. Fourth, in late neoliberalism, between 2016 and 2021, the average growth rate of the Brazilian economy was 1.2%.

Lula’s third term has the daunting task of reigniting long-term economic growth by increasing capital accumulation to 4% annually. For this, the net investment in 2021 should be multiplied by four, corresponding to an investment rate of around 25% with the current capital productivity. The possibilities for expanding the investment rate are either by increasing the profit rate or by adopting a new development strategy with the abandonment of neoliberalism.

There is a contradiction between expanding the investment in infrastructure and reindustrialization with raising the profit rate. Mechanization is not associated with increasing profit rates in developing countries (Marquetti, Ourique, and Morrone, 2020b). On the contrary, in the long term, increasing labour productivity is associated with the capital intensification and the decline in profit rates.

Therefore, the abandonment of neoliberalism and its replacement for a new institutional framework capable of combining higher economic growth, employment, and environmental preservation is the path for Brazilian development. Restoring capital accumulation and reaching low emissions is a challenge for the government. Marquetti, Mendoza Pichardo, and Oliveira (2019) show that in developing countries, higher capital accumulation requires environment-saving technical changes to mitigate emissions. It is well known that countries have relied on energy intensity to boost their economies (Von Arnim and Rada, 2011).

Any attempt to reindustrialize the economy using industrial policies should also consider macroeconomic policies. It is necessary to coordinate the industrial strategy and the short run macroeconomic policy to succeed in reindustrialization (Nassif, Bresser-Pereira, and Feijó, 2018). In the long term, it is necessary to have a strategic development plan. Pochmann (2022) referred to the need for the Brazilian state to resume economic planning. Moreover, it is fundamental to embrace the construction of a new set of state-owned enterprises to expand investment in Brazil. Roberts (2022) pointed out that state-owned enterprises have played a role in Chinese development, maintaining high investment rates despite declining profit rates.

One of the challenges facing Lula’s government is the absence of sources to induce economic growth. In the first decade of the 21st century, the commodity boom was the source of growth induction. The increase in demand for commodities expanded the investments by public and private enterprises and generated the fiscal resources for rising public investment. During Lula government, the extractive industry expanded 42% and the services 37%. The new government pointed to the reindustrialization of the Brazilian economy. However, it is unclear what will be the industrial policy and whether the manufacturing sector will function as engine of the economic growth.

During the Temer and Bolsonaro governments, the agricultural sector led economic growth, expanding 21% between 2016 and 2021, reaching 8% of value added in Brazil. Bolsonaro received strong political support from the agricultural sector. Both governments adopted a late neoliberal agenda, prioritizing a wage squeeze in order to promote a resumption of private investment. However, the agricultural sector is not able to provide economic dynamism for a country with an urban and complex economy with a large population like Brazil.

Transformations in the capitalist economy in the last decade have put neoliberalism on the defensive. Even the IMF, a central supporter of neoliberalism, has drawn attention to the fact that neoliberal policies, rather than achieving economic growth, increase inequality and jeopardize long-term growth (Ostry, Loungani, and Furceri, 2016). Indeed, there are clear political limits to implementing a developmentalist strategy for economic development.

6. FINAL REMARKS

The article investigated the perspectives of Lula’s third government in Brazil by looking at the profit rate and its determinants from 2000 to 2021. The profit rate and its determinants in 2021 were similar to those found in the early 2000s, particularly capacity utilization and profit share. Perhaps, the main difference is that the profit rate was declining in 2002. Currently, the profit rate is rising due to the expansion of profit share and capacity utilization.

Comparing the current situation with that of 2002 situation gives an overview of the challenges facing the new government. An economic policy capable of increasing demand through redistribution to the poor and expanding labor share may boost economic activity in the short term. It may also be essential to consolidate the political coalition that supported Lula election and to contain the opposition. However, the limits represented by the Goodwin cycle can begin quickly in the current period.

The main challenge for the government is the expansion of capital accumulation. After 1980 capital accumulation and GDP growth plunged with the profit rate decline and neoliberalism. There are indirect references in the new government documents about raising capital accumulation, such as reindustrialization and higher investments in infrastructure.

In addition, higher long-term capital accumulation and growth require a departure from neoliberalism. Developing countries that relied primarily on competitive forces could not catch up; the profit rate tends to decline with faster capital accumulation.

Simply put, long-term capital accumulation and growth in the Brazilian economy will return only if a new set of non-neoliberal institutions are properly restored. The main results can be summarized as follows:

1. Economic success depends on political and policy spaces.

2. Rebuilding developmentist institutions are part of the solution for the new government.

3. Redesign and stimulate state enterprises to boost capital accumulation and output growth.

4. There is a need for the convergence between industrial and macroeconomic policies.

5. Only a departure from neoliberalism can spur output growth.

These are crucial elements that policymakers should consider. The trajectory of the profit rate presents opportunities and dilemmas for the new government. Exploring the opportunities and circumventing the class dilemmas involved in fostering economic growth through government policies is pivotal to the new government’s success. Even if there is short-term success in spurring growth, the government could have difficulty promoting greater changes due to political restraints. The Brazilian bourgeoisie does not sign a departure from the central tenets of neoliberalism. Unfortunately, economic prospects remain bleak even for a highly skilled politician like Lula.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)