Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas

Print version ISSN 0185-1276

An. Inst. Investig. Estét vol.28 n.89 Ciudad de México Sep. 2006

https://doi.org/10.22201/iie.18703062e.2006.89.2226

Artículos

Marriage Almanacs in the Mexican Divinatory Codices

Elizabeth Hill Boone

Tulane University.

Abstract

When Friar Motolinía recalled the five kinds of Aztec painted books, he said the fifth pertained to "the rites, ceremonies, and omens [...] relating to marriage." Although no pictorial codices that are wholly dedicated to marriage fates and ceremonies have survived, several extant codices do contain individual almanacs that show marriage ceremonies and give marriage prognostications. They tell the potential couple whether their union will be happy and successful, challenging, difficult, or disastrous, and in what ways; often they also foretell whether and how children will come into the union. Cognate versions that appear in the "Borgia Group" codices from the Mixteca and Puebla/Tlaxcala reflect ideas about marriage fates that are documented for the Aztecs as well as Mixtecs. This unity of understanding shows that much divinatory ideology was widely shared in Late Postclassic Central Mexico.

Resumen

Cuando fray Motolinía recuerda los cinco tipos de libros aztecas pintados, dice que el quinto pertenece a "los ritos, ceremonias, y presagios [...] relacionados con el matrimonio". Aunque ningún códice pictórico que esté completamente dedicado a las fiestas y ceremonias del matrimonio ha sobrevivido, algunos códices existentes sí contienen almanaques individuales que presentan ceremonias matrimoniales y que dan pronósticos del matrimonio. Ellos dicen a la pareja potencial si su unión será feliz y exitosa, desafiante, difícil o desastrosa, y en qué modos: frecuentemente también predice cómo y de qué manera los hijos llegarán a la unión. Las versiones cognadas que aparecen en los códices del "Grupo Borgia" de la Mixteca y Puebla/Tlaxcala reflejan ideas sobre el destino matrimonial que están documentadas para los aztecas, así como para los mixtecos. Esta unidad de entendimiento demuestra que mucha de la ideología adivinatoria fue ampliamente compartida en el Posclásico tardío en México central.

Writing in 1541 from Tehuacan, Mexico, to his patron in Spain, the Franciscan friar Toribio de Motolinía reflected on the knowledge he had gained of Aztec customs and lifeways.1 Much of this knowledge, he said, came from the "ancient books" that the indigenous people had, books "written in symbols and pictures" rather than in letters, but efficacious nonetheless. Motolinía divided the world of Aztec books into five genres, pertaining variously to the realms of history, religion and ritual, dreams and omens, and baptism and the naming of children, among other subjects. One particular genre, he noted — the fifth one — pertained to "the rites, ceremonies, and omens of the Indians relating to marriage." Marriage was an extremely important institution for the Aztecs and their neighbors. Through marriage, new households were created, families were joined, children were produced and raised, and political alliances were forged. Polygamy, which was common among rulers and other elite men who could afford numerous wifes, added even more complexity to familial units and connections. For these reasons, it mattered whom one married.2

Of the marriage books Motolinía mentioned for the Aztecs specifically, none has survived. Instead, the contents of such books have come down to us as fragments scattered in different sources and mixed with other kinds of data. The huehuetlahtolli (the speeches and admonitions of the elders) that were recited prior to and on the occasion of a marriage have been preserved in the compilations and writings of sixteenth-century investigators of Aztec culture, such as Andrés de Olmos, Motolinía, Bernardino de Sahagún, Alonso de Zorita, and an unnamed friar connected with Horatio Carochi.3 We know something about the use of matchmakers, the selection of partners, and the marriage ceremony also from descriptions by Motolinía, Sahagún, Zorita, Juan de Torquemada, and, for the Mixtecs, Antonio de Herrera.4 The ceremony itself, as it was carried out in the Valley of Mexico, is pictured and textually described in the third (ethnographic) section of the Codex Mendoza (60v-61r); a Yope version is painted and glossed in the Codex Tudela (74rv).5 Marriage customs are noted or described by a number of other chroniclers as well.

What Motolinía called "the omens [...] relating to marriage" are likewise mentioned by some of the early colonial authors, and they are visually articulated in several Preconquest codices. Such omens determined the identity of the bride and the quality of the match, as well as the timing of the marriage ceremony. As Motolinía described it, once a young man's family decided it was time he married, the elders tentatively identified a bride and called on a calendar priest, master of the signs and fates, to say whether her signs and birthday were compatible with his.6 If so — and only if the signs were agreeable — would they dispatch the matchmakers, the old women, to solicit the woman's hand from her parents. When an agreement had been reached, the elders on the young man's side sought out a good day for the ceremony; these good days, according to Sahagún, were Reed, Monkey, Crocodile, Eagle, and House.7

Such prognostications, like most of the others in Mesoamerica, were tied to the Mesoamerican divinatory calendar of 260 days. This sacred calendar operated independently from the 365-day "solar" calendar, and although the two ran concurrently, it was the 260-day calendar that carried prognosticatory meaning. Diviners and calendar priests understood portents and determined fates by knowing the supernatural forces that accompanied and gave meaning to the different units and cycles within the calendar. This sacred calendar was composed of twenty day signs (Crocodile, Wind, House, Serpent, etc.) that combined consecutively with thirteen numbers (1-13). Thus, the day 1 Crocodile was followed by 2 Wind, 3 House, 4 Serpent, and so forth, to yield 260 individually named days. The twenty day signs by themselves formed a basic count of twenty days, and the thirteen numbers formed another count of thirteen days, called trecenas, so that within the 260-day cycle, separate smaller cycles of thirteen and twenty were also running. To these units — to the signs, the numbers, and the trecenas — prognosticatory meanings were attached, in the form of deities, supernatural essences, cosmic directions, and other forces. This meant that each day — each combination of a day sign and number — came with many layers of augural meaning. Each day thus had its special character.

A person's nature and proclivities were determined by the augural meanings attached to the day on which he or she was born. Someone born on 1 Crocodile, for example, would carry the fates attached to the sign Crocodile, to the number 1, and to the first trecena (the trecena that begins with 1 Crocodile); someone born on 2 Wind, would also carry the fates attached to the first trecena but would have the different auguries that came with Wind and the number 2. Since the fates of Mesoamerican men and women were governed by the days on which they were born, we can see why it was so important to know the birthdays of one's prospective marriage partner.

The ancient prognostications attached to the signs, numbers, and trecenas as they relate to success in marriage survive in marriage almanacs preserved in three preconquest divinatory codices. These books (all members of the so-called Borgia Group) are the Codex Borgia, Codex Laud, and Codex Vaticanus B, books that were painted in central and southern Mexico — in the area of Tlaxcala, Puebla, and Oaxaca that includes Cholula in the north and the Mixteca in the south.8 The marriage almanacs they contain correspond to Mixtec and Zapotec practices as well as to Aztec practices, for a common divinatory system that was shared over much of central and southern Mexico in the century before the Spanish invasion.9

The marriage almanacs in these books all relate calendrical units to images of a male and female interacting with each other, sometimes also with children. The identity and actions of the painted couples, plus the accoutrements and discrete symbols that accompany them, signal to the diviner whether the union of the human couple will be happy and successful, challenging, difficult, or disastrous, and in what ways. Some almanacs also foretell how many children, if any, will come into the union, whether they will be boys or girls, and whether they will thrive.

Three kinds of marriage almanacs are found in the extant codices, and they are physically structured so as to link calendrical units to the augural images in two ways. The most common, which seems to be the principal type of its genre, adds together the day numbers of the man's and woman's birth days to reach numerical sums (from 2 to 26) that it associates with twenty-five different couples. It relies on the combined day numbers to reveal the fate of a marriage. The other almanacs are structured to record marriage prognostications for groups of days. They seem to reveal the suitability of a group of days for a marriage ceremony and may also tell whether a man or woman born during those days will succeed in marriage. One of these types associates the different trecenas (the thirteen-day periods) to four wedding scenes that are themselves associated with the cardinal directions. The other type associates different groups of days to six distinctive marriage pairs.

Combined Day Numbers

The first type of marriage almanac appears in cognate versions in all three codices (Borgia 58-60, Laud 33-38, and Vaticanus B 42b-33b).10 Several chroniclers — Motolinía, thinking of the Nahuas; Juan de Córdova, speaking about the Zapotecs; and Antonio de Herrera, referring to the Mixtecs — also allude to the kind of information this variety of almanac offers. The fact that three surviving codices contain it and three colonial chronicles (writing about different ethnic groups) refer directly or indirectly to this kind of almanac suggests that it was the principal type of the marriage genre.

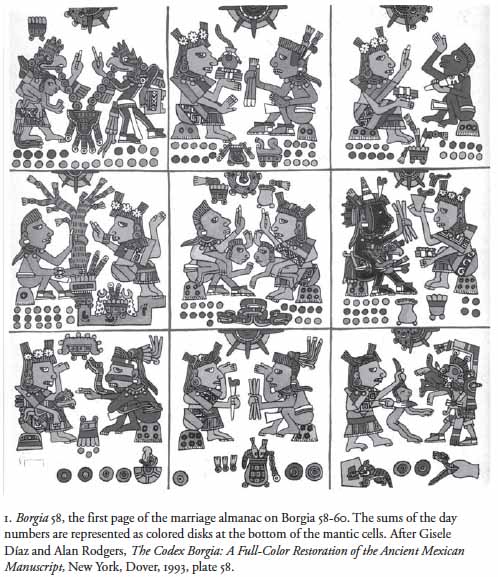

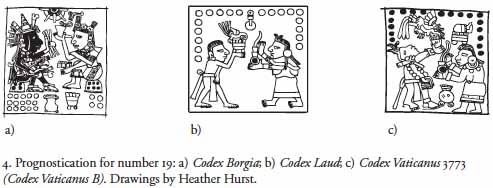

This type of almanac stands out from the other almanacs in the divinatory corpus because it is not concerned with the twenty day signs or the full 260-day count, as are almost all the other almanacs. Rather it focuses on the numbers of the day names and is one of the very few almanacs in the divinatory corpus to describe day number fates explicitly. Since the day numbers are 1 through 13, the numbers in this almanac are 2 through 26, which is the sum of the day numbers of two persons. In twenty-five rectangular cells, which are arranged in a linear sequence, the almanac records the numbers 2 through 26 as colored disks, and depicts a male and female interacting, often with accoutrements, symbols, and offspring (figs. 1, 2).

Structurally this type of almanac is organized as a simple list: the 25 cells simply follow one another, as do the elements in a list, running horizontally along one to three registers (fig. 2). The Borgia version winds in a boustrophedon pattern along three registers of pp. 58-60: beginning in the lower right of p. 58, it reads right to left, then left to right, and then right to left again across all three pages, to end in the upper left of p. 60. The Laud version fills two registers of pp. 33-38, beginning in the lower right of p. 33 and running right to left, then left to right in the upper register to end in the upper right of p. 33 again. The version in the Vaticanus B flows right to left along the lower register of pp. 42-33.

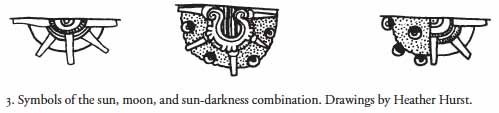

The Borgia version of this almanac presents males and females costumed as specific, identifiable supernaturals (fig. 1). They manipulate objects, gesture, interact with each other, and are accompanied by symbols and implements of ritual, which together create the augural message. At the top of most of the Borgia scenes are additional symbols that represent the sun, moon, or a combination of sun and darkness (fig. 3). In contrast, the versions of the almanac that appear in the Laud and Vaticanus B are very similar to each other and somewhat different from the Borgia (figs. 4, 5, 6). They share imagery the Borgia does not have, they are iconographically simpler than the Borgia, with fewer recognizable supernaturals, and they lack the sun, moon, and sun-darkness symbols at the top of each scene. The Borgia almanac thus stands apart as being richer and constructing its own version of the basic message.

Eduard Seler, the early master of the divinatory codices who first recognized the similarity of the Borgia, Cospi, Fejérváry-Mayer, Laud, and Vaticanus B and grouped them together under the term "Borgia Group," read this type of almanac very differently from what is suggested above. As in so many of his interpretations, an astral paradigm guided this one. Largely because a sun, moon, or sun-darkness symbol appears at the top of most of the scenes in the Borgia, Seler suggested that the scenes had directional connotations and referred to the six regions of the cosmos: east, north, west, south, up, and down.11 Pushing the astral perspective even further, he opined that the scenes also referred to "the 13 nocturnal hours and the 13 hours of the day." Because he read the females in each scene as manifestations of Xochiquetzal, whom he identified as a young moon goddess, he thought the presentation could also be called "the 25 aspects of Xochiquetzal;" in this lunar interpretation, the sun, moon, and sun-darkness symbol represented day, nightfall and days when the moon is visible in the evening sky, and morning sky.12

Subsequent publications of the Codex Laud have generally followed Seler's reading. Cottie Burland, in an article that briefly describes the Laud's contents, posed the rhetorical questions of whether it was more likely that the almanac was associated with Xochiquetzal or whether it was related to the monthly rhythms of a woman's life.13 José Corona Núñez simply summarized Seler's general reading.14

Seler's mistaken analysis was finally corrected by Karl Anton Nowotny in his structural study of the divinatory codices.15 Because Nowotny focused more on the structure and calendrics of the almanac than on the meaning of the figures and symbols, and because he was not constrained by Seler's overarching astral perspective, he correctly read the numbers 2 through 26 as the combination of two sets of day numbers, which allowed him to recognize the presentation as a marriage almanac.16 To this end, he noted that Córdova explained that the fate of marriages among the Zapotecs was determined by adding the day numbers of the man and the woman.17 Nowotny also pointed out that almost half of all possible combinations of day numbers total 11 through 17, and he noticed that most of the positive fates were also concentrated in these numbers, which bespeaks a positive perspective on marriage.18

It was insightful of Nowotny to draw upon Córdova's reference to Zapotec marriage fates, because this is exactly the kind of information that is presented in the painted almanacs. Córdova speaks about marriage prognostications in the very back of his Zapotec grammar. After Córdova describes the divinatory calendar, he explains that the fate of a potential marriage was based on "the sum of the names" [we presume the day names] of the bride and groom.19 Using this system, for example, a man born on 10 Serpent who wished to marry a woman born on 6 House, would look to the fate associated with 16.

Similarly Herrera mentions the importance of the couple's day numbers when a bride is chosen among the Mixtec nobility, and he adds further information.20 He notes that a man could not marry a woman with the same day number as his, that his day number should be higher than hers. Although this particular restriction is not borne out by the Mixtec historical codices,21 Herrera's statement nevertheless indicates that the Mixtecs also paid attention to the couple's day numbers.

In the surviving pictorial examples of this type of marriage almanac, many of the prognostications are clearly positive or negative, but others are ambiguous or speak to one particular aspect of a relationship. For example, the man and woman of number 19 offer precious objects to each other: he holds a quetzal or parrot, and she a stack of kindling and an incense pan (in the Borgia) or a ball of rubber (in the Laud and Vaticanus B ) (fig. 4). These and the full, upright vessels surely bode well for the marriage. Likewise, a flowering tree placed between a man and woman (number 5) symbolizes abundance.22 In contrast, a scorpion placed between the man and woman of number 14, where the man has also turned away, suggests the sting of a hurtful relationship. The couple of number 2 is accompanied by at least one dead child, depending on the codex, and the man is costumed as the death lord Mictlantecuhtli (fig. 1, lower right). In the Borgia and Vaticanus B versions, the male is shown devouring one of the infants; in the Borgia, his wife slits the throat of another. This pairing of a man and a woman whose day numbers are both 1 is extremely inauspicious for children; if born into the union, they do not survive. In addition to being a rare numerical combination, it reflects Herrera's admonition against the man and woman having the same day number.

Number 24 presents a case of infidelity and deceit (fig. 5). The message is explicit in the Borgia, where the wife, who holds a quetzal to symbolize her worth, has caught her husband fondling a mostly nude woman. The symbol of shield and spears (the common Aztec symbol for war) states the obvious conflict. The message is subtler in the Laud and Vaticanus B versions: the woman still holds her quetzal, but the temptress is gone and the memory of this deceit remains only in the lizard that the man holds. The lizard seems to function here as a symbol of male sexuality. In the Laud, the man speaks (lies, actually) to his wife (his speech scrolls are like curls of excrement), but in the Vaticanus B it is the lizard who actually tells the tale, and a shield-and-spears symbol again emphasizes the conflict. As Nowotny noted, negative fates tend to be concentrated at the lower and higher numbers, which are less likely to occur, although there is also considerable variation from number to number, and many fates combine positive and negative aspects.23

In comparison with the versions in the Laud and Vaticanus B, the Codex Borgia consistently elaborates and embellishes the message of its marriage prognostications, as it does with so many of its almanacs. It also includes symbolic images that the Laud and Vaticanus do not. Such are the celestial symbols — a sun, a moon, or a combination of sun and darkness — that appear at the top of twenty-two of the twenty-five scenes in the Borgia (fig. 3). Although Seler read these symbols as representing specific astronomical phenomena, I propose that they should not be read as astronomical or scenic elements but as symbols that add mantic meaning to their cells. The sun disk ordinarily signifies the daylight hours and perhaps lightness in general, and the moon in a circle of night sky symbolizes generalized night or darkness. The sun is also associated with marriage generally, as a positive feature. An adage recorded by Sahagún uses the sun as an analogy for marriage itself: "'He setteth out his sun.' This is to say, he is married. The woman especially says: 'I discover my sun; I set out my sun.' "24 In the marriage almanacs painted in the Codex Borgia these celestial symbols probably signify a positive (sun), negative (moon), or mixed (sun-darkness) prospect.25

In the early colonial period, the Spanish friars also equated lightness and the sun with Christ and spiritual enlightenment, developing a solar Christ metaphor that continues today in some indigenous populations.26 Equally, the friars linked darkness with evil and sin. When Sahagún described a prognostication for a new born child, his Nahuatl text spoke of a broken sun, which his Spanish text explained is "half good, half bad."27 Although the opposition of good and evil, salvation and sin is firmly a Christian construct — and we should not facilely apply it back to the central Mexicans — the preconquest meaning of the sun and moon may nevertheless have been generally similar. The original indigenous pairing more probably relates to the antithetical pairing of order (the sun and daylight hours) and chaos (night), which was fundamental in central Mexico.28

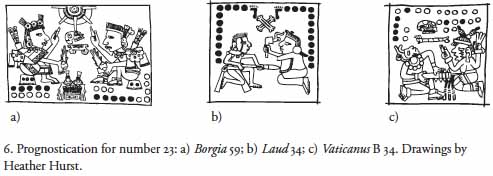

The way the sun, moon, and sun-darkness symbols are employed in the Borgia version of this marriage almanac supports their reading as positive, negative, and mixed forces. The symbols add to the general prognostication of the figures and other mantic elements in the cells, but they do not always parallel it. Rather, they seem to function independently, contributing their own meaning. They correlate not with the imagery but with the day numbers. All the odd numbered totals (3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 21, 23, 25) except 9 have the sun disk, and the sun disk appears only with these odd numbers. The even numbered totals have as symbols either the moon (6, 18), a vessel with offerings (4, 16), or the sun-darkness combination (2, 8, 10, 12, 14, 20, 22, 24, 26). This correlation holds regardless of the relevant scenes, which sometime contradict the positive and negative meanings of the symbol. For example, the moon symbol with number 18 is at odds with the peaceful couple who hold two children in that mantic cell (fig. 1, middle scene of second register). The sun symbol with number 23 (fig. 6) does not accord with that couple, who are accompanied by a skull and bone, bloody hearts, and a cuauhxicalli (vessel for hearts and blood). In the Vaticanus B and Laud versions, the man even stabs his wife in the stomach with a sharp spear or is about to do so.

The key to the meaning of these symbols lies in comments made by Córdova and Motolinía. When Córdova spoke about reaching a marriage prognostication by adding the [calendar] names of the bride and groom, he was focusing on the likelihood of children. Accordingly, he said that the total sum of the two names was to be divided by two, and if any number were left over (if the division were not exact), the couple would have a son. Then the original sum was to be divided by three, and if any number were left over, the couple would have another child; then it would be divided by four and then by five, and if any number remained after each, other children would follow. Using this system, the sums of 7, 11, 13, 19, and 23 promised the most offspring, and all the even numbers prevented sons. This general preference for odd numbers recalls an observation that Motolinía made when he spoke about the inauguration of a new lord. He said that when someone in Tlaxcala, Huejotzingo, Cholula, and their environs was being initiated as a lord (tecuhtli ), they (presumably the calendar priests) sought an odd numbered sum to help them set the day of the initiation. To reach this sum, they added the person's birth day number to the number of his initiation day to achieve this odd number.29 Thus, someone born on an odd numbered day would be inaugurated on an even numbered day, and someone born on an even numbered day would be inaugurated on an odd numbered day. But Motolinía also indicated that someone born on an odd numbered day might also have been married on an odd numbered day, and would then need to be initiated on an odd numbered day. This emphasis on odd numbered days and sums suggests that the odd numbered sums were more beneficial than the evens when marriage was concerned.

We see this in the Borgia almanac, where the sun symbol accompanies all the odd numbers except 9, which is divisible by 3. When the negative or positive meaning of the symbol contradicts the other imagery in the mantic cell, it likely refers to children. The appearance of the sun disk with the violent couple of number 23, for example, suggests that this number is a good total for the birth of children but not for other aspects of the marriage.

These marriage scenes have more nuance and subtlety than simply indicating success or failure in a marriage. Objects appear and are manipulated meaningfully, and the couples pose and gesture. Although, we do not understand the full symbolism of a number of the objects and of most of the poses and gestures, which can vary somewhat from manuscript to manuscript, we still can usually understand the essentials of the augury.

Marital Scenes

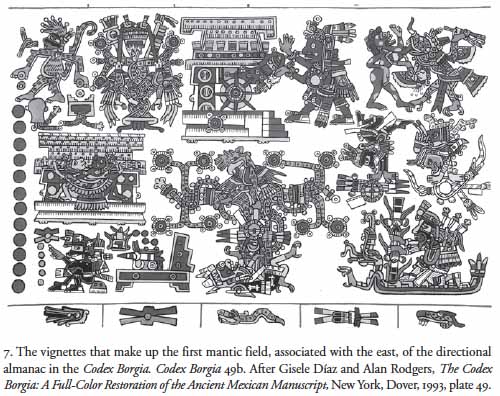

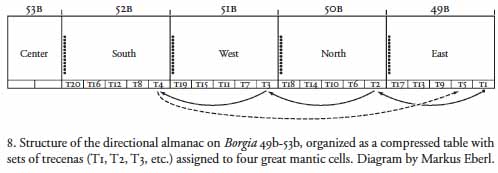

A second type of marriage almanac focuses visually on the marital union itself and concerns itself not with the couple's day numbers but with groups of days that may be auspicious or hazardous for marriage. The prognostications are carried by scenes of supernatural couples who appear beneath marriage blankets in houses. This almanac appears only in the Codex Borgia, where it is only one component of a very complex and mantically rich almanac that spans Borgia 49b-53b (figs. 7, 8). In this almanac, four great mantic cells (49b-52b) pertain to the cardinal directions — east, north, west, south — while the final smaller cell (53b) pertains to the center.30 Each of the mantic cells is filled with ten separate vignettes that contribute prognosticatory meaning relative to that direction (fig. 7). In the center of each large cell is a directional tree on which is perched a bird; on the right a figure drills a new fire; at the top a supernatural or deity impersonator makes an offering in front of his temple. The seven other scenes or elements pack in additional layers of meaning.

Of specific interest to the present discussion of marriage fates is the vignette on the left side of each large cell, which pictures a male and female embracing within a house and covered by a blanket (fig. 9). This is clearly a representation of marital union. The man and woman have the coloring and costuming of particular deities, and their house has distinctive features that give it a specific character. It is their identity as gods and their physical situation in the different abodes that convey the quality of the marriage.

Groups of days are brought into association with these mantic scenes by an organizational structure that I call a compressed table.31 As in a table, the almanac organizes the 260-day count into five groups of fifty-two sequential days that are presented in a parallel manner: if it were a full table, the organization could be conceptualized as five rows each of fifty-two days, the rows stacked as parallel registers.32 The compression comes when these groups of fifty-two days are divided into four equal sets of thirteen days, the trecenas. The trecenas are identified by their beginning day signs, which are pictured below the large mantic cells. The other twelve days in the trecenas are then represented by twelve disks, which are stacked in a column on the left side of the mantic cell. This almanac reads from right to left, the count jumping from scene to scene (fig. 8). One thus begins with the first days sign (Crocodile, T1) in the far right below the first scene, counts out the twelve other days of that trecena (the spacers within the scene), to reach the first day sign ( Jaguar, T2) below the second scene, and so forth. Once the count has moved through all four mantic cells once, it returns to the first cell to begin again with the fifth trecena (Reed).

For the trecenas associated with the east (the 1st, 5th, 9th, 13th, and 17th trecenas), solar beings within a jeweled and flowered structure signal prosperity and success (fig. 9). For the trecenas associated with the north, Tlazolteotl (goddess of childbirth, weaving, and filth) joins with a Macuiltonaleque (deceased warrior?, solar figure) in or on a white mound with thorny flowers to characterize a less positive union, which will be fed by the blood of decapitated figures. The western trecenas, with Chalchiuhtlicue (goddess of groundwater) and Tepeyollotl (Heart of the Mountain) in a maize temple, promise success as fine as in the east. The south trecenas, however, are dire; marriage is the union of the lord and lady of death within a bone temple.

These four little scenes embedded within the larger directional presentation offer up marriage prognostications, perhaps with respect to the timing of the ceremony. Considering the prosperity suggested by the eastern and western pairs, one would probably want to set the marriage date in an eastern or western trecena. Sahagún's evidence supports this idea. He notes that once a man and woman agreed to marry, they "sought a day of good fortune [...] a sign of good disposition," among which, he said, were Crocodile, Monkey, Reed, and Rain.33 Crocodile and Reed begin the trecenas associated with the east, which are characterized as lush, bountiful, and prosperous; the sun god and a solar female are under a multi-colored blanket within a jeweled and flowery house. Rain and Monkey begin two of the trecenas associated with the west; here it is the earth deity Tepeyollotl and the water goddess Chalchiuhtlicue who lie beneath a fringed blanket within a jeweled house topped with a ripe ear of maize. Both scenes bode extremely well for the marriage.

The Six Marriage Pairs

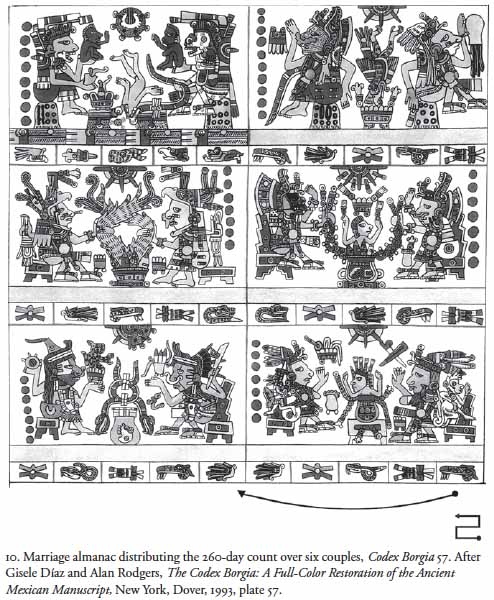

The third type of marriage almanac is structured in a similar manner. It is organized as a compressed table that associates groups of days to varied scenes, but here the scenes number six (fig. 10). Within these mantic cells, marriage pairs are seated opposite and, usually, facing each other. They pose, gesture, and handle implements, as they do in the first almanac discussed. Cognate versions are found on Borgia 57 and Fejérváry-Mayer 35b-37b.34 In the Borgia this almanac directly precedes the first marriage almanac discussed (which employs the couple's day numbers), and like that almanac, its scenes also have the sun, moon, and sun-darkness symbols at the top of the cells (fig. 3). Because of these celestial symbols, Seler saw these two almanacs as being conceptually similar and, predictably, associated the six scenes of this almanac with "the six heavens" or the six realms of the cosmos: east, north, west, south, up, and down.35 Corona Núñez reiterated Seler's interpretation.36 Again, it was Nowotny who correctly recognized it as a marriage almanac.37

Like the other compressed table almanac, this one organizes the 260-day count into five groups of fifty-two sequential days. However the groups are here divided into six unequal sets. The first day of each set is pictured below the mantic cell to which it is associated, and the other days in that set are represented by disks within the cell itself. The Borgia almanac reads in a boustrophedon pattern from scene to scene: from lower right to left, middle left to right, and then upper right to left.38 The count begins with Crocodile in the lower right corner and then continues through the seven spacers in the first mantic cell to reach the ninth day sign, Water, which is the first day sign below the next mantic cell to the left. Then one counts through the seven spacers in that mantic cell to reach the next sign (Movement), which is the first day sign below the next cell ( just above), and so forth. Each pass through the six scenes covers fifty-two days. After one passes through the six scenes once, the count moves to the second sign below the first scene (Reed) and counts through the almanac again, to Crocodile under the second scene, Water under the third scene, and so forth. One passes through the almanac five times to complete the 260-day cycle. The spacers in the six mantic cells number 7, 7, 7, 7, 10, and 8, which means that the first four cells pertain to successive eight-day periods (sign + 7), and the last two cells to eleven days and nine days respectively.39

In each mantic cell a seated male and female supernatural manipulate offerings and symbols and interact with each other. In this almanac, the males and females are complementary deities: reading sequentially, they are male and female versions of Tonacatecuhtli (Lord of Sustenance), male and female pulque gods, male and female maize deities, the water gods Tlaloc and Chalchiuhtlicue, the flower gods Xochipilli and Xochiquetzal, and male and female death gods.40

Three of the pairs offer prognostications that are clearly positive: the gods of sustenance, maize, and water in the first, third, and fourth positions are associated with jewels and other symbols of preciousness and abundance. The last pair is dismal in the extreme: between the death lords a man and a coral snake descend head first and are being swallowed by the skeletal earth.41 The other two pairs are slightly less dire but still ominous. The male and female pulque gods in the second position have vessels of flint knives and a jaguar between them; in the Borgia they brandish a stone or obsidian ball and an axe, and they have coral snakes and a skull vase between them. The message seems to be one of mutual antagonism. The flower lords Xochipilli and Xochiquetzal in the fifth position have turned their backs on each other and have turned over their offering vessels; this cannot signal a compatible, happy union, despite the precious bowl and descending quetzal between them in the Borgia.

At the top center of each mantic scene in the Borgia is the sun, moon, or sun-darkness symbol seen in the first Borgia marriage almanac. The sun symbols occur with the three most positive prognostications, and the moon occurs with the death lords, but exact matches are not made with the two other couples. The antagonistic pulque gods, who lack any beneficial or positive signs, have the sun-darkness (variable) symbol. And the incompatible flower gods have the sun symbol above them. This is further evidence that these sun, moon, sun-darkness symbols in the Borgia are not meant to summarize the scene below them but to contribute additional mantic information that then becomes part of the whole prognostication.

Marriage almanacs such as this and the one just previously discussed, which indicate the forces that govern sets of days, reveal the character of these days for the institution of marriage. They can easily be used to determine an auspicious time for the marriage ceremony, and this may have been their primary function. But they can also be used to identify the generalized marriage fate for each partner. A male born on a day in an eastern trecena, for example, would have some assurance of prosperity and happiness, especially if he married a woman born also on an eastern day or on a day in a western trecena. A male born into the northern trecena, with its skeletal imagery, might see cause to worry about his marital future, and he might seek a woman whose birthday came in a better trecena, if she would have him.

In the last almanac, the sets of days are more variable, and the six mantic scenes overlap irregularly with those of the directional almanac. The first sets of days in both almanacs are positive, and the last sets are negative, but the days between them may be positive in one almanac and negative in another. It is likely that both almanacs were used concurrently, along with several other almanacs in the divinatory books, to reach a richly textured and nuanced reading.

The principal or most important marriage almanac, however, seems to be that which combines the day numbers of the male and female. This is the almanac that has survived in three of the existing Precolumbian codices, and this is the almanac whose message is alluded to by Motolinía, Córdova, and Herrera. In the Borgia, this almanac directly follows the other marriage almanac. In the Vaticanus B it runs parallel to and on the same pages as the almanac for the birth of children.

Of course every divination involved a host of factors. The calendar priests had a great range of almanacs at their disposal — not solely those relating specifically to marriage — and a proper prognostication would involve readings taken from several different almanacs. An indication drawn from one would have to be weighed against factors drawn from many others, so that rarely was a divination fully negative or flawlessly positive.

The divinatory act was also a performative act, a time of interaction between the book, the diviner, and the individual or couple seeking guidance. A reading was an opportunity for the diviner to learn about the families whose children wished to marry, to see what the images said about these children, and to convey to them the characteristics of their potential union. It was also a time to warn families and couples of the special rewards and challenges they might face in their marriage. In preconquest Mexico a good marriage was built on many things, including the compatibility of the couple's day signs and numbers.

Notas

1. Friar Toribio de Motolinía, Motolinía's History of the Indians of New Spain, Francis Borgia Steck (trans. and ed.), Washington, D.C., Academy of American Franciscan History, 1951, p. 74. [ Links ]

2. For marriage rules with respect to kinship organization among Aztec rulers, see Pedro Carrasco, "Royal Marriages in Ancient Mexico," in H.R. Harvey and Hanns J. Prem (eds.), Explorations in Ethnohistory: Indians of Central Mexico in the Sixteenth Century, Albuquerque, University of New Mexico Press, 1984, pp. 41-81. [ Links ] For marriage customs and patterns among Mixtec nobles, see Barbro Dahlgren, La Mixteca: su cultura e historia prehispánicas, Mexico City, Imprenta Universitaria, 1954, pp. 147-156, 329-334; [ Links ] and Ronald Spores, The Mixtec Kings and Their People, Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, 1967, pp. 10-13. [ Links ]

3. Andrés de Olmos, Huehuetlahtolli: Testimonios de la antigua palabra, Miguel León-Portilla (intro.) and Librado Silva Galeana (trans.), Mexico City, Secretaría de Educación Pública /Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1991, pp. 113-140; [ Links ] Motolinía, Memoriales o libro de las cosas de Nueva España y de los naturales de ella, Edmundo O'Gorman (ed.), Mexico City, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México-Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, 1971, pp. 311-315; [ Links ] Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex: The General History of the Things of New Spain, Charles E. Dibble and Arthur J. O. Anderson (trans. and eds.), Santa Fe, School of American Research and the University of Utah, 1953-1982, bk. 6, pp. 127-133; [ Links ] Alonso de Zorita, Life and Labor in Ancient Mexico: The Brief and Summary Relation of the Lords of New Spain, Benjamin Keen (trans. and ed.), New Brunswick, New Jersey, Rutgers University Press, 1963, pp. 139-151; [ Links ] Frances Karttunen and James Lockhart (eds.), The Art of Nahuatl Speech: The Bancroft Dialogues, Los Angeles, University of California at Los Angeles, Latin American Studies, 1987, vol. 65, pp. 109-127. [ Links ]

4. Motolinía, Memoriales, pp. 315-320; Sahagún, Florentine Codex, bk. 6, pp. 127-133; Zorita, Life and Labor in Ancient Mexico, pp. 133-134 and 139-140; Juan de Torquemada, Monarquía indiana: de los veinte y un libros rituales y monarquía indiana, con el origen y guerras de los indios occidentales, de sus poblazones, descubrimiento, conquista, conversión y otras cosas maravillosas de la mesma tierra, Miguel León-Portilla (ed.), Mexico City, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1975-1983, vol. 4, pp. 156-198; [ Links ] Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas, Historia general de los hechos de los castellanos en las islas y tierra firme del Mar Océano, Ángel González Palencia (ed.), Madrid, Tipografía de Archivos, 1934-57, vol. 6, pp. 320-321. [ Links ]

5. The Codex Mendoza, Frances F. Berdan and Patricia Rieff Anawalt (eds.), Berkeley, University of California Press, 1992, 60v-61r; [ Links ] Códice Tudela, José Tudela de la Orden (comp.), Madrid, Cultura Hispánica, 1980, vol. 2, pp. 288-289. [ Links ]

6. Motolinía, Memoriales, pp. 316-317.

7. Sahagún, Florentine Codex, bk. 6, pp. 128-129.

8. Codex Borgia. Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana (Messicano Riserva 28), Karl Anton Nowotny (intro.), Graz, Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt, 1976; [ Links ] Codex Laud. MS. Laud Misc. 678, Bodleian Library, Oxford, Cottie Burland (intro.), Graz, Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt, 1966; [ Links ] Codex Vaticanus 3773 (Codex Vaticanus B), Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Ferdinand Anders (intro.), Graz, Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt, 1972. [ Links ] For the provenience of the Borgia Group codices, see Elizabeth Hill Boone, "A Web of Understanding: Pictorial Codices and the Shared Intellectual Culture of Late Postclassic Mesoamerica," in Michael E. Smith and Francis F. Berdan (eds.), The Postclassic Mesoamerican World, Salt Lake City, University of Utah Press, 2003, p. 241; [ Links ] and Elizabeth Hill Boone, Cycles of Time and Meaning in the Mexican Divinatory Codices, Austin, University of Texas Press, 2007, pp. 211-230. [ Links ]

9. Boone, "A Web of Understanding", Cycles of Time and Meaning, pp. 231-233. [ Links ]

10. See Karl Anton Nowotny, Tlacuilolli: Die mexikanischen Bilderhandschriften, Stil und Inhalt, mit einem Katalog der Codex-Borgia-Gruppe, Berlin, Verlag Gebr. Mann, 1961, p. 218. [ Links ] For descriptive readings of the imagery in the Vaticanus B, Laud, and Borgia, see Ferdinand Anders and Maarten Jansen, Manual del adivino. Libro explicativo del llamado Códice Vaticano B, Graz/Madrid/Mexico City, Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt/Sociedad Estatal Quinto Centenario/Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1993, pp. 247-256; [ Links ] Ferdinand Anders and Maarten Jansen, La pintura de la muerte y de los destinos. Libro explicativo del llamado Códice Laud, Graz/Mexico City, Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt/Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1994, pp. 171-173; [ Links ] and Ferdinand Anders et al., Los templos del cielo y de la oscuridad: oráculos y liturgia. Libro explicativo del llamado Códice Borgia, Graz/Madrid/Mexico City, Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt/Sociedad Estatal Quinto Centenario/ Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1993, pp. 309-322. [ Links ] For a summary of the almanac in the Borgia, see also Bruce Byland, "Introduction and Commentary," in Gisele Díaz and Alan Rodgers, The Codex Borgia: A Full-Color Restoration of the Ancient Mexican Manuscript, New York, Dover, 1993, pp. XXIX. [ Links ]

11. Eduard Seler, Codex Vaticanus No. 3773 (Codex Vaticanus B): An Old Mexican Picture Manuscript in the Vatican Library. Published at the Expense of His Excellency the Duke of Loubat, Berlin and London, T. and A. Constable, 1902-1903, pp. 211-242; [ Links ] Codex Borgia. Eine altmexikanische Bilderschrift der Bibliothek der Congregatio de Propaganda Fide. Hrs. auf Kosten Seiner Excellenz des Herzogs von Loubat, Berlin, Gebr. Unger, 1904-1909, vol. 2, pp. 178-208; [ Links ] Comentarios al Códice Borgia, Mariana Frenk (trans.), Mexico City, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1963, vol. 2, pp. 149-172. [ Links ]

12. Seler, Codex Vaticanus No. 3773, p. 241; Codex Borgia, pp. 207-208; Comentarios al Códice Borgia, vol. 2, pp. 171-172.

13. Cottie Burland, "Some Descriptive Notes on MS. Laud Misc 678, a Pre-Columbian Mexican Document in the Bodleian Library of the University of Oxford," 28th International Congress of Americanists, Paris, 1947, p. 372; [ Links ] Carlos Martínez Marín (trans. and ed.), Códice Laud, Mexico City, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 1961, p. 22. [ Links ]

14. José Corona Núñez, Antigüedades de México, basadas en la recopilación de Lord Kingsborough, Mexico City, Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público, 1964-1967, vol. 3, pp. 382-393. [ Links ]

15. Nowotny, Tlacuilolli, p. 218.

16. Idem; Nowotny, "Kommentar," in Codex Borgia, 1976, pp. 32-33, 36, 43.

17. Juan de Córdova, Arte del idioma zapoteco, facsimile of 1886 edition, Nicolás León (ed.), Mexico City, Toledo/Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 1987, pp. 216-217. [ Links ]

18. Nowotny, Tlacuilolli, p. 218.

19. Córdova, Arte del idioma zapoteco, pp. 216-217; discussed in Anders and Jansen, Manual del adivino, p. 82; La pintura de la muerte, pp. 171-173.

20. Herrera, Historia general, vol. 6, p. 320.

21. Dahlgren, La Mixteca, p. 148; Mary Elizabeth Smith, Picture Writing of Ancient Southern Mexico: Mixtec Place Signs and Maps, Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, 1973, p. 29. [ Links ]

22. In the Dover edition of the Codex Borgia (Díaz and Rodgers, The Codex Borgia), one of the five numerical disks was not reproduced, so only four disks are pictured instead of five.

23. Nowotny, Tlacuilolli, p. 218.

24. Sahagún, Florentine Codex, bk. 1, p. 81.

25. Karl A. Taube, "The Bilimek Pulque Vessel: Starlore, Calendrics, and Cosmology of Late Postclassic Central Mexico," Ancient Mesoamerica, vol. 4, 1993, p. 3, [ Links ] has read the half sun, half night combination as a "darkened sun" or "half covered sun," which privileges sunset rather than sunrise and implies that the sun disk stands specifically for that celestial body as a prior entity that is being inflicted by the oncoming darkness (i.e., darkness as an agent that acts upon the nominal sun); this makes the symbol an event. I prefer instead to read the sun/night combination nominally, as a static pairing of equal opposites.

26. Louise Burkhart, "The Solar Christ in Nahuatl Doctrinal Texts of Early Colonial Mexico," Ethnohistory, vol. 35, no. 3, 1988, pp. 234-256. [ Links ]

27. Sahagún, Florentine Codex, bk. 6, p. 198; Burkhart, in "Solar Christ" points out that Sahagún was a chief proponent of the solar Christ metaphor.

28. Jeanette Favrot Peterson, "Nigra sum sed Formosa: The Black Christ of Chalma and the Virgin of Guadalupe in Mexico," paper presented in the symposium, Black Christs in the Americas, Spellman College, 1998 (draft of 11/23/00). [ Links ]

29. Motolinía, Memoriales, p. 341.

30. Seler, Comentarios al Códice Borgia, vol. 2, pp. 85-103; Nowotny, Tlacuilolli, pp. 230-233; Anders, Jansen, and Reyes García, Los templos del cielo, pp. 261-277.

31. Elizabeth Hill Boone, "Beyond Writing," in Stephen Houston (ed.), The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp. 313-348. [ Links ]

32. Such is the organization of the in-extenso almanacs that appear on the pages 1-8 of the Borgia, Cospi, and Vaticanus B, Boone, Cycles of Time, pp. 75-78, 121-132.

33. Sahagún, Florentine Codex, bk. 3, p. 40.

34. The imagery of the Borgia and Fejérváry-Mayer versions is described in Anders et al., Los templos del cielo, pp. 305-308, and Ferdinand Anders et al., El libro de Tezcatlipoca, Señor del Tiempo. Libro explicativo del llamado Códice Fejérváry-Mayer, Graz/Mexico City, Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt / Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1994, pp. 281-286. [ Links ] For a summary of the Borgia version, see also Byland, "Introduction and Commentary," pp. XXII-XXIX.

35. Eduard Seler, Codex Fejérváry-Mayer. An Old Mexican Picture Manuscript in the Liverpool Free Public Museums (12014/M). Published at the Expense of His Excellency the Duke of Loubat, Berlin and London, T. and A. Constable, 1901-1902, pp. 182-193; [ Links ] Seler, Codex Borgia, vol. 2, pp. 170-178; Seler, Comentarios al Códice Borgia, vol. 2, pp. 141-148.

36. Corona Núñez, Antigüedades de México, vol. 4, pp. 256-261.

37. Nowotny, "Kommentar", pp. 32, 38, 43.

38. The Fejérváry-Mayer version reads right to left along the bottom register of pp. 35-37.

39. Because of the regular pattering of the six sets of days, a diviner skilled in the 260-day almanac would recognize that all the day signs painted under the first scene are days with the coefficient 1, those of the second scene are 9, those of the third scene are 4, those of the fourth are 12, those of the fifth are 7, and those of the sixth are 5.

40. Another almanac, which exists in cognate versions in the Fejérváry-Mayer (23b-25b), Vaticanus B ( 9a-11a), and Porfirio Díaz Reverse ( 39-35), distributes six pairs of figures over 40 days as a grouped list. Anders, Jansen, and their co-authors refer to them as the six conversations (Anders and Jansen, Manual del adivino, pp. 185-189; La pintura de la muerte, pp. 283-288; Anders et al., El libro de Tezcatlipoca, pp. 237-240. This almanac probably does not offer marriage auguries because its pairs are not uniformly male and female. The Fejérváry-Mayer and Vaticanus B versions employ spacers and allot no days to the final scene. The Porfirio Díaz Reverse version omits the final scene.

41. In the Fejérváry-Mayer (37), the male has his eyes closed in death as he sinks into the maw of the earth lord.