Genus Bulbinella

Twenty-three (23) species of Bulbinella Kunth are known, of which 17 grow naturally in southern Africa, and six in New Zealand (Moore 1964, Perry 1999, Manning & Goldblatt 2010). Bulbinella is monophyletic with Eremurus M. Bieb, Kniphofia Moench. and Trachyandra Kunth as sister genera (Devey et al. 2006, Naderi Safar et al. 2014). However, Bulbinella is characterized by, and can be separated from the closely related genera, by possessing the following features in combination: racemes simple and densely flowered, perianth stellate and persistent, and smooth filaments (Smith & Van Wyk, 1998).

Bulbinella has an interesting and unusual highly disjunct distribution between South Africa and New Zealand. The populations are separated by approximately 11,575 km, which includes the Indian Ocean. Within Bulbinella, the species are often separated by subtle morphological differences such as leaf color and size, height of the plant, and flower color (Perry 1999). Perry (1999) did a comprehensive revision of the South African species based on morphological characters, describing morphological features in great detail. Until now, this genus has, to the best of our knowledge, not been studied at the molecular level.

The aim of our paper is to stress the need of a molecular phylogeny to describe the phylogenetic relationships among the species in the genus and to determine whether the geographically separated populations (South Africa and New Zealand) really form part of the same genus.

Bulbinella consists of 23 species, including B. angustifolia (Cockayne & Laing) L.B.Moore, B. barkerae P.L.Perry, B. calcicola J.C.Manning & Goldblatt, B. cauda-felis (L.f.) T.Durand & Schinz, B. ciliolata Kunth, B. divaginata P.L.Perry, B. eburniflora P.L.Perry, B. elata P.L.Perry, B. elegans Schltr. ex P.L.Perry, B. gibbii Cockayne, B. graminifolia P.L.Perry, B. gracillis Kunth, B. hookeri (Colenso ex Hook.) Cheeseman, B. latifolia Kunth, B. modesta L.B.Moore, B. nana P.L.Perry, B. nutans (Thunb.) T. Durand & Schinz, B. potbergensis P.L.Perry, B. punctulata Zahlbr. B. rossii (Hook.f.) Cheeseman, B. talbotii L.B.Moore, B. trinervis (Baker) P.L.Perry, and B. triquetra (L.f.) Kunth. These species will be described briefly according to their geographical distribution.

Main morphological and ecological characteristics of Bulbinella from New Zealand

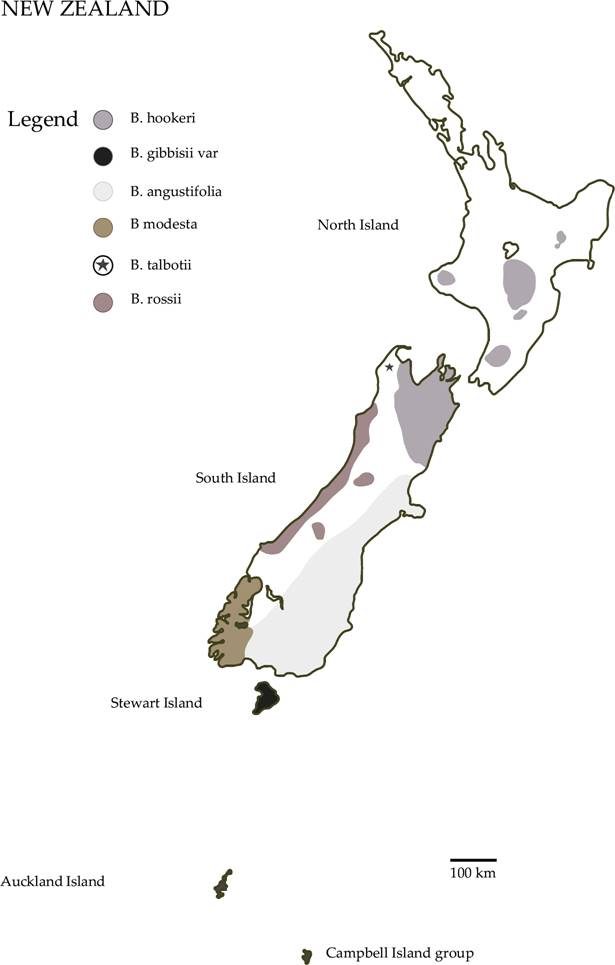

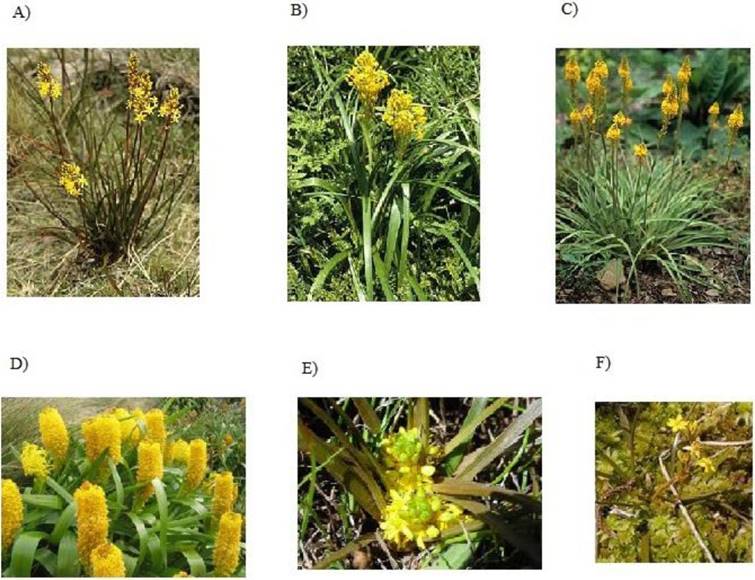

Six species of Bulbinella growing naturally in New Zealand are known (Figure 1): B. angustifolia (Figure 2A), B. gibbii (Figure 2B), B. hookeri (Figure 2C), B. modesta (Figure 2D), B. rossii (Figure 2E), and B. talbotii (Figure 2F). The species are entirely allopatric (Figure 1) (Moore 1964, Milicich 1993), but they all share habitats with high water content (Milicich 1993), including permanent bogs, banks of streams or rivers, and seepage sites in wet grassland, usually on shaded slopes (Milicich 1993).

Figure 1 Distribution of Bulbinella species from New Zealand. [Source: Adapted from Milicich, 1993].

Figure 2 The species from New Zealand. [A) Bulbinella angustifolia, (http://www.hebesoc.org). B) B. gibbii var. balasifera, (http://www.hebesoc.org). C) B. hookeri, (http://www.hebesoc.org). D) B. rossii, (http://www.nzpcn.org.nz). E) B. talbotii, (http://www.nzpcn.org.nz). F) B. modesta, (http://www.nzpcn.org.nz)] (New Zealand Plant Conservation Network, Sarah Beadel).

The new roots, which are formed each year, function as storage organs and swell to a long fusiform shape. The stem is erect, up to 60 cm long with a terminal raceme. The flowers of all New Zealand species are yellow (Figure 2), borne on flexible pedicles, subtended by small, leaf-like bracts, and produce a faint scent. Their ovaries are green in flowers and young ripening capsules, changing through amber to brown and drying prior to dehiscence (Moore, 1964, Milicich 1993). The observed visitors of the flowers of some populations of Bulbinella angustifolia, B. gibbii, B. hookeri, and B. modesta include honey bees, flies, and bugs, suggesting that these insects are likely to be involved in Bulbinella pollination (Milicich 1993). Seed dispersal is most likely ballistic (Milicich 1993, Perry 1999).

Species from New Zealand

Bulbinella angustifolia

Bulbinella angustifolia (Figure 2A) is approximately 40 cm tall. It is usually smaller than Bulbinella hookeri and hermaphroditic (Moore and Edgar, 1970). Most plants produce racemes with 50 flowers or fewer, but some may produce more flowers (Moore, 1964; Milicich, 1993). The current conservation status of Bulbinella angustifolia is not threatened, hence it is under the least concern category according to New Zealand Plant Conservation Network (Moore & Edgar 1970, Thorsen 2009). This species has clumping growth habit and is common in high mountain grasslands at the east of the Southern Alps, from north Canterbury to South Island (Milicich 1993).

Bulbinella gibbii

The common names of this species are “Gibbs Maori Onion”, “Gibbs Lily”, or “Gibbs Onion”. Bulbinella gibbii (Figure 2B) is more similar to Bulbinella rossii in morphology than to B. hookeri except that B. gibbii is much more robust (Milicich 1993). Two varieties of Bulbinella gibbii have been proposed, Bulbinella gibbii var. gibbii and Bulbinella gibbii var. balasifera L.B.Moore. Bulbinella gibbii var. gibbii is smaller (30 cm tall) than B. gibbii var. balasifera from the mainland, and produces fewer flowers per raceme (40 or fewer) (Milicich 1993). However, both varieties of Bulbinella gibbii are gynodioecious (Moore & Edgar, 1970). The inflorescences are prominent and cone-shaped when open. Bulbinella gibbii var. balasifera has a widely disjunct distribution pattern (Moore 1964, Milicich 1993). Bulbinella gibbii is endemic and restricted to Stewart Island (Milicich 1993). The current conservation status of Bulbinella gibbii var. gibbii is at risk and naturally uncommon according to the New Zealand Plant Conservation Network, whereas Bulbinella gibbii var. balasifera is not threatened (Moore et al. 1970, Thorsen 2009, De Lange et al. 2009).

Bulbinella hookeri

Bulbinella hookeri (Figure 2C), also known as “Maori Lily”, grows up to 1 m tall and is hermaphroditic (Moore & Edgar 1970). It flowers between November and January. The inflorescences can easily be seen above the erect leaves (Milicich 1993). Some populations, especially those of Mount Stokes and Cobb Valley, have blue-green glaucous-green leaves and peduncles (Milicich 1993). The current conservation status of the species is considered to be of least concern according to the New Zealand Plant Conservation Network (Moore & Edgar 1970, Thorsen 2009).

Bulbinella modesta

Bulbinella modesta (Figure 2F), is closely related to Bulbine hookeri (Milicich 1993) and differs from all the species described for New Zealand in its short and very slender, less than 30 cm stem (Moore, 1964). This species is hermaphroditic (Moore & Edgar 1970, Milicich 1993). The peduncles are spindly and delicate, and the racemes of most plants are composed of 10-20 flowers, although some have been observed to have more. The leaves are similar in length (20-75 cm × 30 mm wide) to those of Bulbine hookeri, but in Bulbine modesta they are considerably thinner and have a prostrate growth habit rather than erect, as in Bulbine hookeri (Moore 1964, Milicich 1993). The current conservation status of Bulbinella modesta is at risk according to the New Zealand Plant Conservation Network (Moore et al. 1970, Thorsen 2009, de Lange et al. 2009) because they are only known from the lowland alluvial forest of the West Coast Island (Milicich 1993).

Bulbinella rossii

Bulbinella rossii (Figure 2D), is commonly known as “The Ross Lily”. It is a very stout species, reaching a height of up to 1 m (Moore & Edgar 1970, Thorsen 2009, De Lange et al. 2009). The inflorescence is a cylindrical raceme of up to 60 cm long and is made up of more than 50 flowers with short (1 cm) pedicels (Moore 1964; Moore & Edgar 1970, Milicich 1993). This species is considered as “at risk and naturally uncommon” according to the New Zealand Plant Conservation Network (De Lange et al. 2009). It is endemic to New Zealand’s subantarctic Auckland and Campbell Islands (Milicich, 1993).

Bulbinella talbotii

The common names of this species are “Talbot’s onion” and “Gouland Downs’s onion”. Bulbinella talbotii (Figure 2E) differs from all other Bulbinella in its stumpy growing habit with leaves spreading horizontally (Moore 1964). It is much smaller than B. modesta and the peduncles are very short, making the inflorescences barely visible (Milicich 1993). The leaf rosette reaches 10-40 cm in diameter. This species is hermaphroditic (Moore & Edgar, 1970, Thorsen 2009, de Lange et al. 2009). The roots are swollen proximally and it flowers from December to January (Moore & Edgar 1970). The current conservation status of B. talbotii is at risk and naturally uncommon according to the New Zealand Plant Conservation Network (Moore & Edgar 1970, Thorsen 2009, de Lange et al. 2009). It is endemic to South Island, northwest Nelson, and Gouland Downs areas (Milicich 1993).

Morphological and ecological characteristics of Bulbinella in South Africa, compared to New Zealand

Species of Bulbinella are tufted, deciduous solitary geophytes varying from 0.25 to 1 m in height. They have erect rhizomes, basal linear leaves, and numerous stellate flowers in a dense raceme (Perry 1999, Milicich 1993). In South African species the roots may be evenly swollen along their entire length, fusiform, or with apical tubers. In New Zealand species only fusiform roots are found. Leaf sheaths may have prominent nerves that form a fibrous sheathing neck. This feature is found in most South Africa species, but never in New Zealand species.

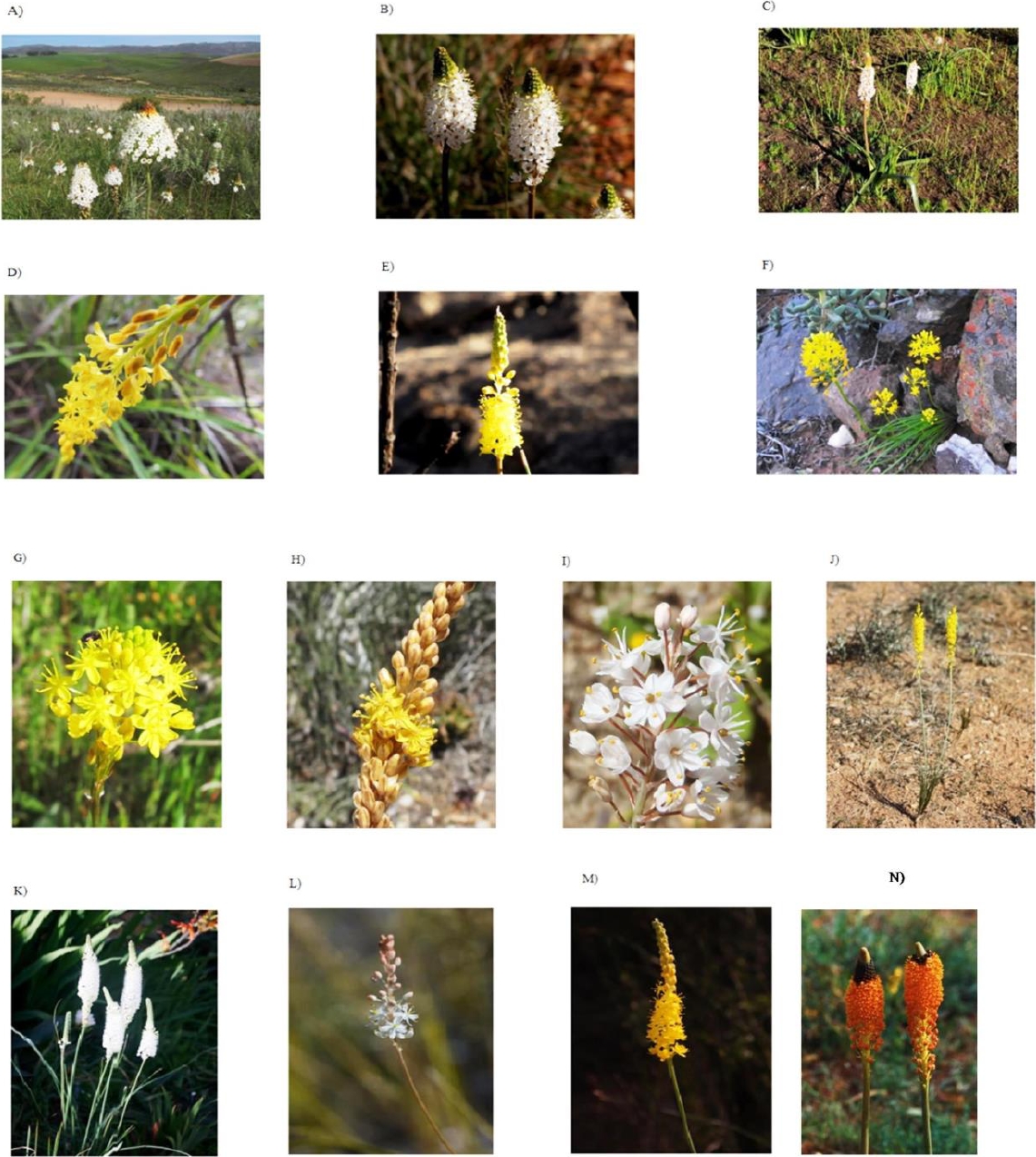

The color of the tepals of South African species varies from white, with a pink central stripe in some species, through ivory, cream, and yellow to bright orange (Perry 1999). In New Zealand all species have yellow flowers (Milicich 1993). Flowering in South African species occurs from late July to December and in all cases coincides with their respective wet season (Perry 1999, Milicich 1993).

Pollination in South African species is carried out by insects, notably honeybees (Boatwright & Manning 2010, Manning & Goldblatt 2010). Most species of South Africa prefer moist, cool habitats, and peaty, acid, and sandy soil (Boatwright & Manning 2010; Manning & Goldblatt 2010). The genus Bulbinella favors cold or cool, wet habitats in both countries (Perry 1999).

Even though Bulbinella species are widely distributed in South Africa, a significant number of species are considered as vulnerable or under least concern (von Staden et al. 2011). The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) places Bulbinella potbergensis and Bulbinella calcicola as critically endangered (Helme & Raimondo 2005, von Staden et al. 2011). Currently, none of the habitats of these species are formally conserved and a population reduction of 90 % is expected in the next 10 years due to habitat quality loss as a result of human development, mining, and agriculture, with the recent introduction of ostriches as well as exotic plant invasion (Helme & Raimondo 2005, von Staden et al. 2011).

Species from South Africa

Bulbinella barkerae

Bulbinella barkerae (Figure 3A) is up to 0.6m tall and readily separated from the other species with ciliate margins (such as Bulbinella ciliolata) based on locality and also on the broader and fewer leaves. The strong-smelling flowers are characteristics of Bulbinella barkerae, which separates it from Bulbinella cauda-felis, a similar species (Perry 1999). It is considered as of least concern under the IUCN criteria (Raimondo et al. 2009). Bulbinella barkerea is confined to the Caledon, Bredasdorp, and Riversdale districts of Western Cape in South Africa (Perry 1999).

Figure 3 The species in South Africa. A) B. barkerae. B) B. cauda-felis. C) B. eburniflora. D) B. chartacea. E) B. elegans. F) B. gracillis. G) B. triquetra. H) B. calcicola. I) B. nutans. J) B. divaginata. K) B. graminifolia. L) B. trinervis. M) B. punctulata (http://www.ispotnature.org) N) B. latifolia (dip.sun.ac.za) (SANBI- Species Dictionary).

Bulbinella calcicola

This is a recently described species similar to Bulbinella triquetra but differs in its broader, channeled leaves with narrowly cylindrical racemes and flowers that are orange-tipped (Manning & Goldblatt 2010). It is considered as critically endangered A3c (Raimondo et al. (2009) under the IUCN criteria (Raimondo et al., 2009). It is restricted to the limestone outcrops around Jacobsbaai close to Saldanha (Manning & Goldblatt, 2010).

Bulbinella cauda-felis

Bulbinella cauda-felis (Figure 3B), is 0.4-0.8 m high. Bulbinella cauda-felis is a variable species complex, in which it is not easy to discover clear-cut distinguishing features that could justify delimitation of subspecific taxa (Perry 1999). The large dull black seeds and thin walled, pale fawn capsule are considered as significant diagnostic characters for the species (Perry, 1999). The plants could be misidentified as Bulbinella triquetra because of the narrow leaves, but most commonly the leaves have a dilated sheath and somewhat glaucous appearance (Perry, 1999). Its common name is Cat’s Tail Bulbinella, and it is classified under the status of least concern under the IUCN criteria (Raimondo et al. 2009). The species is found in Northern Cape and Western Cape of South Africa.

Bulbinella ciliolata

Bulbinella ciliolata, which is less than 0.6m tall, is easily distinguished from Bulbinella elegans by the fibrous sheath, which is loose and straight whereas sheaths of Bulbinella elegans are compactly reticulate (Perry 1999). Its leaves and inflorescence are similar to those of Bulbinella elegans, but tend to be narrower and more numerous (Perry 1999). This species is restricted to northern Namaqualand on sandy loams of the granite hills (Perry 1999) and is considered least concern under the IUCN criteria (Raimondo et al. 2009).

Bulbinella divaginata

The common name of this species is Geelpiet (Figure 3J). It is up to 0.45m tall and is an easily recognizable and a conspicuously autumn-flowering species. The membranous white cataphylls surrounding the base of the leaves, which show beyond the fibrous remains, is a crucial diagnostic characteristic. Bulbinella divaginata also has an elongated inflorescence, narrow filiform and non-succulent leaves, and a well-developed fibrous sheath (Perry 1999). The species is found on a variety of soil types, from fine clay to sandy and predominantly in the hillier or mountainous areas of Northern and Western Cape in Namaqualand (Perry 1999). Bulbinella divaginata is considered of least concern under the IUCN criteria (Raimondo et al. 2009).

Bulbinella elata

This species is up to 1 m tall. Although it has a close resemblance to Bulbinella latifolia and Bulbinella nutans, it differs in having leaves that are flat, spreading, coriaceous, non-canaliculate, and thinner and more delicate when pressed than those of Bulbinella latifolia. In nature, Bulbinella elata also normally flowers earlier in the season than Bulbinella latifolia and Bulbinella nutans (Perry 1999). Bulbinella elata is considered of least concern under the IUCN criteria (Raimondo et al. 2009) and prefers clayey or granitic soils in Northern Cape and Western Cape (Boatwright & Manning, 2010, Manning & Goldblatt 2010).

Bulbinella eburniflora

This species is about 0.75 m tall. The characteristic that makes Bulbinella eburniflora distinct is the ivory-white flowers which habitually have a strong musty odor. The leaves are narrow and semiterete as in Bulbinella elegans and Bulbinella ciliolata (Figure 3C). The fibrous sheath in Bulbinella eburniflora is fine, soft, and somewhat reticulate, whereas in Bulbinella ciliolata it is straight and loose, and in Bulbinella elegans intricately reticulate (Perry 1999). The species is considered to be vulnerable under the IUCN criteria (Raimondo et al. 2009) and is commonly found in Northern Cape, Bokkeveld Escarpment.

Bulbinella elegans

Bulbinella elegans (Figure 3E), is around 0.6 m tall. It is morphologically similar to Bulbinella triquetra, but taller (Perry 1999). Bulbinella elegans also has broader leaves than Bulbinella triquetra. Furthermore, Bulbinella elegans has dead fibers solidly compacted and more intertwined than the shorter, straighter, and looser fibers of B. triquetra. It possesses a dense reticulate fibrous sheath, which separates it from Bulbinella ciliolata, which has a loose straight fibrous sheath (Perry 1999). The white flowered form of Bulbinella elegans occurs in the Sutherland and Laingsburg districts, mainly in Renosterveld on sandy or shale-derived soils (Perry 1999). The lemon-yellow form appears to be confined to western mountain Karoo vegetation of the doleritic and Dwyka clays in the Nieuwoudtville area (Perry 1999). The species is considered least concern under the IUCN criteria (Raimondo et al. 2009).

Bulbinella nutans and B. latifolia

Bulbinella nutans (Figure 3I) grows up to 0.8 m tall. It is often difficult to distinguish from B. latifolia Kunth. They are morphologically similar, and both form large seasonal stands in seasonally wet areas. Bulbinella nutans can be distinguished from B. latifolia by its broader and shorter inflorescence (Perry 1999). However, they can be difficult to identify when pressed. The main difference between Bulbinella nutans and Bulbinella latifolia is in size, with Bulbinella latifolia being taller (up to 1 m) (Perry 1999). There are also differences in their leaves. The leaves of Bulbinella latifolia are significantly broader, arched, and more spreading than those of Bulbinella nutans, which are erect and narrow. Bulbinella latifolia is found in the Northern Cape and Western Cape and is considered to be vulnerable under the IUCN criteria (Raimondo et al. 2009). Bulbinella nutans occurs from north Cape Peninsula to Loeriesfontein and east Swellendam (Boatwright & Manning, 2010, Manning & Goldblatt 2010).

Bulbinella gracillis

This species is up to 0.3 m tall (Figure 3F). The absence of dead leaf remains forming a fibrous sheath around the stem and leaf bases is not encountered in any other Bulbinella species in South Africa, except in Bulbinella gracilis (Perry 1999). In addition, the patent pedicels in the fruiting stage are unique to Bulbinella gracilis and Bulbinella nana. The almost terete leaves are considerably more succulent and the small inconspicuous, boat- shaped bracts are similar to but smaller than those of the two autumn-flowering species, Bulbinella trinervis and Bulbinella divaginata. Bulbinella gracillis is found in the Northern Cape from Richtersveld as far south as Nuwerus (Perry 1999) and it is considered least concern under the IUCN criteria (Raimondo et al. 2009).

Bulbinella graminifolia

Bulbinella graminifolia, (Figure 3K), which is up to 0.65m tall, is closely related to Bulbinella cauda-felis, but is distinguished from that species by its considerably finer, reticulate fibrous sheath. Furthermore, the fruit and the seeds of Bulbinella graminifolia are just about half the size of those of B. cauda-felis. The inflorescence of Bulbinella graminifolia is shorter than that of Bulbinella cauda-felis and it is also more narrowly cylindrical with flowers purer white and faintly salmon-colored in bud (Perry 1999). It is considered under least concern under the IUCN criteria (Raimondo et al. 2009) and it is confined largely to the Clan William area, where it grows in Renosterveld or among Karroid bushes (Perry 1999).

Bulbinella nana

This is the smallest (0.25 m tall) of the Bulbinella species, forming dainty, delicate-looking plants. It is only known from two collections from the Richtersveld area of the Northern Cape (Perry 1999). The species closely resembles Bulbinella gracilis, but is distinguished by the more numerous and very fine filiform leaves, compared with the more succulent ones of Bulbinella gracilis (Perry 1999). It is considered vulnerable D2 under the IUCN criteria and is rare (Raimondo et al. 2009; Hilton-Taylor, 1996)

Bulbinella punctulata

Bulbinella punctulata (Figure 3M) is unique because of its few leaves, which are comparatively longer and narrower than those of Bulbinella latifolia (Perry 1999). Bulbinella punctulata can reach a height of 0.5-1.0 m and can also be distinguished from the remaining Bulbinella species by its long and narrow inflorescences with yellow flowers (Perry 1999). Another important characteristic useful in its identification is its sheath with loose net-like veins, and the inner cataphyll extending for some distance up the leaves (Perry 1999). It is found in Western Cape and it is classified under the status of least concern under the IUCN criteria (Raimondo et al. 2009).

Bulbinella potbergensis

Bulbinella potbergensis is a medium-sized, very rare species only found on the low Koppies near the Potberg range. It has a close resemblance to Bulbinella punctulata (Perry 1999) but has a single long leaf and neatly reticulate sheath that makes the species unique. It is considered as critically endangered under the IUCN criteria (Raimondo et al. 2009).

Bulbinella triquetra

Bulbinella triquetra (Figure 3G), is up to 0.35 m tall, spring-to-early summer-flowering with the leaves having completed development at flowering (Perry 1999). The Bulbinella triquetra species have narrow leaves with denticulations, trigonous and with finely denticulate margins. Some species such as Bulbinella divaginata and Bulbinella. trinervis are also of similar size and have narrow leaves similar to those of B. triquetra, but their leaves are almost terete (Perry 1999). Bulbinella triquetra has yellow flowers like Bulbinella divaginata but the two are separated by the sheathing leaf bases in Bulbinella triquetra, whereas in Bulbinella divaginata the fibrous sheath is formed from separate cataphylls (Perry 1999). It is considered least concern under the IUCN criteria (Raimondo et al. (2009) and is commonly found in Karroid vegetation from the Cederberg to the Cape Town area and east to the Caledon area in South Africa (Perry 1999).

Bulbinella trinervis

This species is up to 0.4 m tall (Figure 3I) and owing to its narrow leaves may be confused with Bulbinella triquetra, particularly those populations flowering late in the season, in November and December (Perry 1999). The features that clearly separate Bulbinella trinervis from Bulbinella triquetra are the non-sheathing leaf bases, small bracts, and also the smaller seeds. In addition, the bracts are broad and truncate without the more typical attenuate apex, making Bulbinella trinervis a very distinctive species in the Bulbinella genus. The white flowers of Bulbinella trinervis are produced in autumn, whereas Bulbinella triquetra have yellow flowers produced when leaves are fully developed in spring (Perry 1999). It is usually found in Eastern Cape and Western Cape in South Africa (Perry 1999). Bulbinella trinervis is considered least concern under the IUCN criteria (Raimondo et al. 2009).

The economic importance of Bulbinella and related genera in South Africa and New Zealand

Flowering geophytes plants were, throughout the centuries, important to mankind because they form part of civilization and culture (Alam et al. 2013). Numerous medicinal components have been extracted from geophytic plants for the cure of different ailments. Amaryllidaceae, Asphodelaceae, Hyacinthaceae, and Iridaceae have proved to be outstanding, especially for their traditional antimicrobial uses in South Africa (Hutchings et al. 1996, Kornienko & Evidente 2008). Geophytic plants are also utilized as ornamental plants and they form an integral part of the world floriculture industry (De Hertogh & LeNard 1993, Van Wyk et al. 1997; Louw et al. 2002, Van Uffelen et al., 2005). Even though there are countless ornamental plants known today, the geophytic ornamentals are highly valued for their colorful, showy flowers (Bodley et al. 1989, Perry, 1999). Amongst these are also minor bulbs like Bulbine, Bulbinella, and Kniphofia.

There is little information available on the markets of these plants in southern Africa (Bodley et al. 1989, Kleynhans & Spies 2011). Also there are few modern taxonomic revisions of these genera and not much attention has been given to these indigenous bulbous plants of South Africa to date, especially the species of Bulbinella.

These geophytic plants are also noteworthy as they produce a range of chemical compounds that are potentially valuable for medicinal and other uses (Fennell & Van Staden 2001). In addition, Goudling (1971) presented evidence that Bulbinella leaves were made into plaited baskets and floor mats by the Maori people of New Zealand.

Medicinal applications of Bulbinella

In developing countries, with their rich heritage of plant biodiversity, herbal medicine is gaining popularity (Louw 2002, Obici et al. 2008). Many geophytic plants have proven to contain a range of unique biologically active compounds (Louw 2002). Traditional treatments involve mainly the use of plant extracts (Akerele 1993, Saggu et al. 2007). The genus Bulbinella is one of the indigenous geophyte plants of importance to South African traditional healers (Van Wyk et al. 1997). However, there is still a lack of scientific research regarding its genetic profile and unique pharmacological compounds (Louw 2002).

Bulbinella slows down bleeding, dries up acne, soothes cold sores, chapped lips and cracked heels, and sunburn and provides relief from eczema symptoms (Schultz 2013). Bulbinella has also been utilized as a skin toner, as it removes impurities, and in the production of antibacterial liquid and creams because of its healing properties (Schultz, 2013). The related Bulbine Wolf species are generally used in the treatment of ringworms, wounds, rashes, and sores (Bulbine frutescens, Bulbine asphodeloides, Bulbine tortifolia); leaf, root, or tuber decoctions are used for the treatment of diarrhoea and dysentery (Bulbine aphodeloides), eczema (Bulbine latifolia, Bulbine natalensis), venereal diseases (Bulbine alooides, Bulbine asphodeloides, Bulbine latifolia), and rheumatism (Bulbine alooides, Bulbine narcissifolia) (Watt et al. 1962, Hutchings 1996).

Bulbinella derivates contain bulbineloneside A, 4’-O-demethylknipholone-6’-O-ß-D-xylopyranoside (bulbineloneside B), knipholone, and isoknipholone, which have been stated to show antitumor activities against HSC-2 cells (Dahlgren et al. 1985; Kuroda et al. 2003, Bringmann et al. 2008).

Secondary metabolites of Bulbinella species include numerous anthraquinone derivatives, including phenylanthraquinones, as determined by conventional TLC and HPLC analysis (Van Wyk et al. 1995, Kuroda et al. 2003, Bringmann et al. 2008). Phenylanthraquinones produced from plant species of Asphodelaceae are extensively useful as herbal remedies for innumerable ailments, which arise from bacterial and fungal infections (Bringmann et al. 2008). The extracts exhibit higher levels of fungal inhibitors than other herbs, such as ginger and hot peppers (Louw 2002). Phenylanthraquinones are a new class of antiplasmodial substances that are found in several Bulbinella species in roots, such as B Bulbinella floribunda, Bulbinella divaginata, Bulbinella elata, Bulbinella nutans var. nutans, Bulbinella nutans var. turfosicola, Bulbinella punctulata, Bulbinella latifolia, Bulbinella trinervis, and Bulbinella triquetra (Dagne et al. 1994, Bringmann et al. 2008). The co-occurring isofuranonaphthoquinones from the roots of B. capitata have antioxidant and also mild antiplasmodial properties (Bezabih et al. 1997, Majinda et al. 2001, Ntie-kang 2014).

The phenylanthraquinones and isofuranonaphthoquinones extracted from the same species have antiparasitic and antioxidant activity (Abegaz et al. 2002, Habtemariam 2007). Additionally, 10, 7’-bichrysophanol is present in Bulbine, Bulbinella, and Kniphofia and is used by the Basotho, Griqua, and whites of southern Africa for wound healing and as a mild purgative (Smith & Van Wyk 1998; Qhotsokoane-Lusunzi & Karuso 2001). The Bulbinella leaves are long, fairly thick, round, and contain a natural healing sap (Schultz 2013). This sap contains glycoproteins, which have soothing and protective qualities, hence help treating bites from mosquitoes, bees, or wasps (Afolayan 2009, Schultz 2013).

In particular, the name Bulbinella floribunda is used for plants commercially sold at markets in Japan (Kuroda et al. 2003, Bringmann et al. 2008). These have recently been investigated, although no active chemical uses have been reported (Kuroda et al. 2003). Perry (1999) does not accept the name Bulbinella floribunda, and lists it under species insufficiently known, as no type specimen can be traced. According to her, the name has recently been used for large specimens of Bulbinella nutans and Bulbinella latifolia. The broad role of these plants in folk medicine suggests their feasible pharmacological potential (Bringmann et al. 2008).

Bulbine frutescens (L.) Wild, is an ornamental herb that grows widely in Botswana and has been used medicinally to enhance the healing of wounds (Watt & Breyer-Brandwijk 1962, Abegaz 2002). Bulbine frutescens leaf gel cures insect bites, wounds, rashes, acne, blisters, burns, ulcers, cracked lips, cold sores, and ringworm (Dyson 1998). Anthraquinones, knipholone, and isoknipholone isolated from roots are some of the chemical constituents of Bulbine frutescens (Van Staden & Drewes 1994). The roots strengthen the general immune system and also help in healing diarrhea, gall bladder colic, urinary disorders, and venereal disease in humans (Van Wyk et al. 1995). These isolated compounds have antitropanosomal activity. Chrysophanol is found in most genera of the Asphodelaceae and can therefore probably be used as a chemical marker (Klopper et al. 2010).

Bulbine natalensis is widely distributed in the eastern and northern parts of South Africa where it is consumed as a mixture of stem powder and milk for the management of male sexual dysfunction (Van Wyk 1997, Yakubu & Afolayan 2009; Afolayan & Yakubu 2009). Also its leaf sap is extensively used in the treatment of wounds, burns, rashes, itches, ringworms, and cracked lips (Afolayan 2009). To suppress vomiting, diarrhea, convulsion, venereal diseases, diabetes, and rheumatism, the infusion of the roots is taken orally (Pujol 1990, Afolayan & Yakubu 2009).

Livestock feed

Although Bulbinella tissues are reported to be distasteful to livestock (Moore & Irwin 1978, Salmon 1985, Webb et al. 1990), some species such as Bulbinella hookeri and Bulbinella angustifolia are fed to browsers in Goudland Downs’s area in New Zealand (Milicich 1993).

Cultivated species of Bulbinella

Bulbinella latifolia subsp. latifolia, Bulbinella elata and the yellow flowered form of Bulbinella nutans subsp. nutans (Figure 3) are most suitable for garden cultivation and are also the most valuable species for cut flowers (Perry 1999). In Israel and California, Bulbinella latifolia subsp. doleritica has proved popular in cultivation because of the Mediterranean type of climate.

The medium sized plants of Bulbinella cauda-felis (Figure 3B) are promising ornamentals because of their long, narrow inflorescence of pink-tinged white flowers, which can make fine garden plants (Perry 1999). However, its seed might not constantly produce the finest inflorescences, because the species are widespread and very variable in the different areas in which they are found (Perry 1999).

The smaller white flowered Bulbinella graminifolia is not known in cultivation but may be worth trying. Also the Bulbinella eburniflora with a broader inflorescence of ivory-white flowers is a most impressive plant. Both the lemon-yellow and the cream colored forms of Bulbinella elegans are well worth growing and they make neat plants and the venation on the leaf sheath adds to their significance (Perry, 1999).

The smallest Bulbinella species, the spring-flowering Bulbinella triquetra with yellow flowers and the autumn-flowering Bulbinella divaginata, could be grown in a rock garden, but are also the most suitable for container culture (Perry 1999). Bulbinella gracilis, as the name implies, is a graceful plant and probably would make a charming pot plant.

Additionally, Bulbinella nana is the rarest, smallest, and daintiest species, which also makes a good pot plant (Perry, 1999). Bulbinella nana is distinguished from Bulbinella gracillis by its very fine filiform leaves whereas Bulbinella gracillis has more succulent leaves (Perry 1999).

Conclusions and perspectives

The erosion of genetic diversity in plant species has been increasingly severe (Wang et al. 2007, Keneni et al. 2012) and this may probably happen for Bulbinella both in South Africa and New Zealand if conservation aspects such as ex-situ and in-situ conservation are not taken into consideration. There is, therefore, an urgent need for studying the genetic resources of these Bulbinella species. Bulbinella plants, though studied less intensively than other herbs, are of economic importance and further researches could provide useful leads in novel pharmaceutical developments.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)