Introduction

After the Second World Conference on Human Rights held in Vienna in 1993, the United Nations (UN) launched an ambitious program for monitoring the degree of human rights compliance worldwide and for pressuring states into committing to report on their progress in the matter. This program included the creation of a specialized agency (the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights), the creation of liaison offices in each signatory country for monitoring the implementation of the program at the national level and the construction of the most comprehensive and consistent system of human rights indicators in existence. The design and implementation of this program posed various methodological questions. How can we construct a worldwide unified and comparable set of indicators that also sheds light on the relevant dimensions of each human right in the local context? How can we overcome the limitations on data collection in countries without a solid statistical capacity (Würth 2006: 81)? Why should we rely on official sources to measure human rights compliance, especially in cases where states are reported as the main source of human rights violations?

This article aims to address these questions, by analyzing three different methodologies for the construction of human rights indicators. In the first section, we will present the methodologies of budget analysis (Manion et. al. 2017, Matthews and McLaren 2016, Dutschke et. al. 2010), the UN indicator system (Hunt 2003, Malhotra and Fasel 2005, Würth 2006, Vázquez and Serrano 2014) and the standard-centered approach (IACHR 2008, CDHDF 2012). In the second section we apply these approaches to a concrete case related to public advertising in Mexico, and compare the indicators generated with each approach. In the conclusion, we analyze the strengths and weaknesses of each approach and draw some conclusions regarding: a) the kind of indicators they can construct, b) the reliability and versatility of their sources and c) each approach’s adaptability to local contexts.

Challenges for the construction of human rights indicators on freedom of expression

The construction and use of human rights indicators presents several challenges. In the first place, it poses political questions on the usefulness of indicators as a governance tool and as an effective mechanism for expanding human rights. Several international organizations such as the United Nations or the World Bank, conceive the indicators as a valuable tool for promoting accountability and good governance at a national level and for fostering human rights worldwide. In contrast to this conception of indicators as a technically and politically neutral instrument, many authors (Fukuda-Parr and Ely 2015, Engle Merry 2016) have pointed out that indicators have the potential to “alter the exercise and perhaps even the distribution of power in certain spheres of global governance”(Fisher, Kingsbury and Merry 2012: 4). For some of them, indicators are part of a system of control implemented by multilateral organizations trying to impose an agenda or a specific international legal order on countries (McGrogan 2016, Krever 2013: 133). Other authors share this politicized conception of indicators but hold a less critical perspective. Such is the case of René Urueña, who conceives the process of construction of indicators as an arena of political dispute “in which different political agendas face each other to achieve the quantitative expression of their values, interests and ideologies” (Urueña 2014: 547).

Beyond this political discussion, the construction of human rights indicators also presents methodological challenges that are crucial for our analysis. In the first place, it implies an interpretative process for determining the essential core of each right. This process is so controversial, that it is usually subject to debate within national Supreme Courts and the International Courts1. In the case of intangible rights, measurement is even more complex, since there are no concrete references, such as the goods and services provided by the state. In turn, some rights have a higher degree of interdependence with other rights, making it harder to define an essential core and to establish a reduced number of indicators. Such is the case with freedom of expression.

Freedom of expression is one of the elementary rights on which every free, participatory and democratic society is founded. It is a crucial right for the full development of people and is made up of multiple rights, such as the right to access information, the right to exercise freedom of thought, the right to access information and communication technologies, the right to receive information, etc. In turn, it is a “key” right, as it is a necessary condition for the exercise of other rights, such as religious freedom, participation in public affairs or free association.

In the case of Mexico, the right to freedom of expression is threatened through different challenges and requires political responses on different levels. Since 2000, 133 journalists were killed in Mexico in possible relation to their professional work (Article 19 2020). That is why the country is considered the most dangerous in the world for journalistic work (CPJ 2019). In turn, Mexico has one of the highest rates of media concentration in Latin America (Reporters Without Borders / Cencos 2018, Calleja 2012, Jacoby 2012a, Huerta-Wong and Gómez García 2012), especially in the broadcasting sector (Jacoby 2013). The Federal Communications Law approved in 2014 provided an opportunity for the creation of three new open television channels with national coverage, two of which are private and one public. This increase in broadcasters represented substantial progress for the plurality of voices. However, the new public broadcaster started with insufficient financial resources for increasing plurality and diversity in the sector (OECD 2017). Something similar occurs with community media: The new legal framework enabled the legal recognition of social and indigenous media. However, the law prohibits them from selling advertising except to the government, which is obliged to allocate them 1% of its advertising budget. Thus, they cannot obtain private financing, except through donations in money or in kind from the community. These media also have severe difficulties when formalizing their legal situation, since in order to obtain licenses they need to offer proof of financial support through bank accounts, be legally constituted as a civil association and pay a very elevated sum for a technical study carried out by the Federal Institute of Telecommunications (Becerra and Waisbord 2015). Dependence on public financing is problematic, given that the new Social Communication Law approved in May 2018, does not provide clear and objective criteria for the allocation of official advertising, nor does it establish budgetary controls or spending caps in this area (Fundar 2018). In addition, the current government has decided to self-impose a cap of 0.1% of the approved budget, which meant a decrease of close to 50% in 2019 compared to the previous year (Expansión 2019).

When designing strategies to reverse these situations, one of the problems is that the implementation of public policies related to freedom of expression is also fragmentary2. Furthermore, most of the analyses that evaluate freedom of expression in Mexico usually address only one of the multiple dimensions of this fundamental right3. As we pointed out before, the right to free expression is made up of multiple rights and is, in turn, a “key” right to exercise other rights. That is why we consider that in order to consider and evaluate the right to free expression in an integral way, it is essential to simultaneously analyze it in its different dimensions.

The first step to address this problem is to identify the core content of this right. Within the framework of our research project “Freedom of expression in Mexico: A proposal to evaluate public policies on freedom of expression from a human rights perspective”, we selected the following dimensions, taking as reference the main challenges to freedom of expression identified by the Special Rapporteurs for Freedom of Expression of the UN, IACHR, OSCE, and CADHP in 2010 (OAS 2010): 1. Mechanisms of Government Control over the Media; 2. Criminal Defamation; 3. Violence Against Journalists; 4. Limits on the Right to Information; 5. Discrimination in the Enjoyment of the Right to Freedom of Expression; 6. Commercial Pressures; 7. Support for Public Service and Community Broadcasters; 8. Security and Freedom of Expression; 9. Freedom of Expression on the Internet and 10. Access to Information and Communications Technologies.

Once we have identified the main dimensions of this right, we face the challenge of exploring such a vast field without losing depth of analysis. This difficulty is common among the studies of public policy with a human rights perspective: When we put the spotlight on the effective exercise of a right and not a particular public policy, the variables of analysis to be contemplated multiply exponentially. In the following section, we will review different methodological approaches for the elaboration of indicators with a human rights perspective, paying particular attention to the broadness or focus of analysis they allow and to the ways they link public policy analysis with the effective exercise of human rights. After describing these methodological approaches, in the last section of this article, we will apply them to a specific example related to public advertising, in order to illustrate these methodologies and discuss their usefulness.

Methodological approaches to the elaboration of human rights indicators

The human rights discourse burst into the political debate in the context of the French Revolution and began to crystallize later in several documents, beginning with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948. Since then, several research methods consolidated to analyze and measure human rights. Andreassen, Sano and McInerney-Lankford describe a first milestone in human rights research during the decades of 1970 and 1980, when the analysis was primarily in the legal field, with a strong focus on the elaboration and interpretation of human rights standards, and on building new international human rights institutions to monitor and enforce those standards (Andreassen, Sano and McInerney-Lankford 2017:3).

A major breakthrough in human rights research was the Second World Conference on Human Rights held in 1993 in Vienna, when states reached a consensus to monitor not only that human rights were reflected in the laws and constitutions of the countries but also in their public policies (Vázquez and Serrano 2014). In this conference states agreed on a series of measures to begin monitoring their public policies and guarantee the observance of the commitments assumed in the field of human rights. To this end, states were advised to “develop national action plans to improve the promotion and protection of human rights” (par. 71) and they agreed on the “need to create a system of indicators to measure progress towards the realization of economic, social and cultural rights (ESCR)” (par. 98). These initiatives were reinforced as of the year 2000 in the framework of the Millennium Declaration, when states agreed on the consolidation of a standardized system of development indicators, which would progressively lead to the Human Development Index. In this way, the Millennium Declaration related Development and Human Rights in practical and concrete terms, highlighting the role of equality as an effective way to achieve sustainable development (IACHR 2008: par. 22 - 23).

Following the 1993 Vienna Declaration, links began forming between human rights and development, opening analytical space for social scientists and anthropologists, concerned with problems of changes in regimes or conflicts between universal and local norms. The engagement of development economists during this time also contributed to the generation of models and practical guidance for development policies (Andreassen, Sano and McInerney-Lankford 2017: 3-4).

The commitments made during the Congress in Vienna also fostered a shift in human rights researchers from their initial political concerns to a renewed interest in operationalization methods to measure the progress and setbacks of national states in the fulfillment of human rights. In this context and with the support of the United Nations (Güendel et al. 2005: 12) an analytical framework emerged that will be a key reference for our analysis. This framework, known as the “Human-Rights-Based Approach”, is normatively based on international human rights standards and operationally directed to promoting and protecting human rights. Under this approach, the plans, policies and processes of development are anchored within a system of rights and corresponding obligations established by international law (OHCHR 2006: 15).

One of the first reference works in the operationalization of human rights was written by former Special Rapporteur on the Right to Health, Paul Hunt (Commission on Human Rights 2003: par. 6-35). In his work, Hunt suggests distinguishing between structural, process and outcome indicators, in order to evaluate the different moments or aspects of a public policy. He also proposes the concept of “unpacking rights”, to which we will refer later. Since then, different UN programs and university researchers4 have contributed to systematizing the theoretical and methodological framework of the human rights-based approach, in order to reach a common methodology to elaborate indicators with a human rights perspective.

Simultaneously, this also began a process of mapping different human rights, which in 2012 led to the publication of a very comprehensive matrix of indicators called “Human Rights Indicators: A Guide to Measurement and Implementation” (OHCHR (2012).

All these initiatives fostered the creation of national mechanisms and agencies to assess the situation of each state and to elaborate progress reports, contributing substantially to the debate on the use of human rights indicators and the treatment of available sources of information. However, there are still some discrepancies regarding the methodology used to interpret these indicators. In the next section we will present and compare three different approaches when elaborating on these indicators.

Budget Analysis

The first way to address the elaboration of human rights indicators is to analyze the amount of resources assigned to achieve them. Although the allocation of budget resources does not guarantee the effective fulfillment of the rights, the amount committed to the achievement of a right is a relevant indicator of the state’s commitment to certain problems. Budgetary analysis with a human rights approach, does not only allow us to measure how much money is allocated to public policies related to the different rights. It also gives us valuable information on how their obligations to respect, protect and fulfill that right are achieved.

This methodology offers us valuable tools for knowing whether the principles of non-discrimination, progressive achievement and maximum use of available resources are respected in practice and whether the state is fulfilling the minimum core content of the rights, defined as “the nonnegotiable foundation of a right to which all individuals, in all contexts and under all circumstances, are entitled” (Fundar 2004: 73). To draw these conclusions, the methodology of budget analysis requires not only a good management of budget arithmetic, but also of the tools of normative interpretation.

Currently, there are no homogenous criteria within the methodology of budget analysis. As a report of the Food and Agriculture Organization points out: “In this context, ‘methodologies’ mean the type of budget work an organization or institution decides to pursue (…) A few examples are: a) analyzing figures in the government’s budget, for one or more years, by socio-economic analysis (class, sex, ethnic group, etc.) or by sector (health, education, etc.); b) comparing expenditures against allocations; c) undertaking independent tracking of government expenditures, with or without community participation; or d) assessing the impact of government expenditures related to specific programs” (FAO 2009: 39).

This approach has been fostered by different United Nations bodies, by social organizations such as the International Budget Partnership and Fundar (2004) and by academics such as Manion, Ralston, Matthews and Allen (2017), Matthews and McLaren, D. (2016) and Dutschke, Nolan, O’Connell, Harvey and Rooney (2010), among others. It has also crystallized into the very comprehensive United Nations analysis mentioned above (FAO 2009).

Even when there is a consensus regarding the usefulness of this type of analysis when understanding a government´s humans rights priorities and strategies, there are still many problems that cannot be solved through this methodology (Fundar 2004:36): “On the one hand, the analysis of the spent amount, doesn´t provide any information about how effectively or efficiently the resources were spent. On the other hand, this analysis can provide useful information about the resources that were spent, but it cannot determine what should be spent. That is why this analysis should be supplemented with detailed information about the economy, the population, regional issues, and specific programs, in order to have a more complete picture of the fulfillment of a specific right” (Fundar 2004:36). This assertion made by the International Budget Partnership and Fundar will be applied in the following section, when we try to apply this methodology to the study of public advertising in Mexico.

The UN Indicators System

The UN system of indicators is probably one of the biggest efforts to systematize a worldwide set of indicators to measure improvements in human development. This initiative implemented by the United Nations is normatively based on international human rights norms and operationally directed to promote and protect human rights (UN 2003). One of the first attempts to turn this framework into a methodology was made by former Rapporteur on Health, Paul Hunt, who developed the concept of “unpacking rights”. In order to analyze the right to health in different countries, Hunt took as a reference the obligations of states in the field of human rights (respect, protect, guarantee and promote human rights) and combined them with other elements such as the availability, accessibility, adaptability and quality of the goods and services provided by the state - developed, in turn, by the Special Rapporteur on the Right to Education, Katerina Tomasevski. By shifting the focus of analysis from rights to obligations, Hunt developed a valuable tool to operationalize a state’s degree of progress on the effective fulfillment of a given human right. In his report (Commission on Human Rights 2003) he developed a list of 42 indicators for child survival, that served as a reference to start a process of operationalization or “unpacking” of human rights.

Based on the work of Hunt, Rajeev Malhotra and Nicolas Fasel, the UNHCHR (2005) developed a broader analysis, based on quantitative and qualitative indicators. Anna Würth describes the main achievements of their work in the following terms: “Their initial step is to transcend treaty codification of single rights by forming, at least for some rights, broader categories, based inter alia on the interpretation by Treaty Bodies in the General Comments (…). For individual rights, they break down the core elements as defined in the General Comments” (Würth 2006:89). Once they defined the core elements of a specific right, they operationalized its measurement at the level proposed by Hunt: structure, process and outcomes (Malhorta Fasel 2005, Landman 2006). In addition, they employ several qualitative and quantitative indicators for each level.

Among the main advantages of this approach, Anna Würth highlights that it offers “a multi-dimensional, rights-based systematization of Human Rights enshrined in the treaty regime”. Likewise, she considers that it contributes to operationalizing the treaty body interpretation of human rights and that it combines this analysis with levels and units of measurement which enable progress to be tracked (Wurth 2006: 78).

In Latin America, Daniel Vázquez and Sandra Serrano along with Dometille Delaplace are some of the researchers who took up Paul Hunt’s proposal and systematized it in depth (Vázquez and Serrano 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014, Vázquez and Delaplace 2011), while also influencing other researchers in the field (Servín Ugarte 2014, Mondragón Pérez 2015, Bernal Ruiz 2016).

The Standard-Centered Approach

The standard-centered approach has also been developed under the auspices of the United Nations and is closely related to the UN indicators system (CDHDF 2012). The main difference among both approaches are the sources they use for the empirical analysis and the versatility they have to analyze different regional contexts.

The starting point of the standard-centered approach is that within each human right there are different interrelated elements - standards and dimensions 5- and that non-compliance with any of them, compromises the full realization of the right. Therefore, this approach enables a comprehensive analysis of human rights that takes into account their different dimensions and the internal relationship between them as indivisible interdependent and interrelated rights.

In order to analyze the different dimensions and standards, this methodological approach proposes using the international human rights standards offered by the International Human Rights System as a guide. This corpus is made up of the jurisprudence of the international courts, the general observations of the Human Rights Committees, together with the reports of the Special Rapporteurs, and the documents where they develop content on the right from the empirical evidence found during periodic visits to various countries (CDHDF 2012: 18).

As mentioned above, the substantial differences between the UN indicators system and the standard-centered approach are the source those approaches use to monitor the effective achievement of human rights in each country. The UN indicators are mainly based on statistics generated by each member state and should only use other international sources “as means of verification and in absence of national sources” (UNPD 2006: 1).

The use of official sources may be problematic when we intend to use these indicators precisely for evaluating the commitment of states to human rights. Why should we use the official sources of a state considered to be the main aggressor of the press (Article 19 2020) with a judicial system where 99.13 % of the crimes against journalist remain unpunished (Article 19 2019)? On the other hand, as Anna Würth points out, the use of national statistics creates severe problems with data collection.

Sources and methods of data collection remain central to all debates on the quantitative description of human rights-related performance. As a matter of principle, gathering timely and accurate data is a responsibility of the states, their national statistical offices and national human rights monitoring mechanisms, if existent. In fact, however, there is a serious lack of statistical capacity in almost all countries. Even countries with comparatively good statistical capacity often do not sufficiently (or…) may not wish to produce disaggregate statistics. (Würth 2006: 81).

The standard-centered approach, on the other hand, monitors the evolution of each country through the jurisprudence and case-law produced by international courts, the general observations of the UN Human Rights Committees, together with the reports of the Special Rapporteurships and the documents where they develop legal content based on evidence found during their periodic visits to various countries (CDHDF 2012: 18). Over and above Würth’s critical observations on the issues with data collection, it may also be problematic to resort to official statistics to evaluate the performance of the states themselves. In this sense, the material generated by the Special Rapporteurships has the great advantage of being produced by external evaluators, with a deep knowledge of national realities.

The standard-centered approach also offers other advantages. On the one hand, the standards and observations offer a finite, relatively ordered and systematized corpus, which enables an analysis of rights in their different dimensions. On the other hand, they provide an internationally recognized objective parameter to measure the performance of a state in relation to a specific right. Using this corpus as reference also offers reliable and high quality information, since it is based on an exhaustive doctrinal debate among international court judges, as well as on-site visits and first-hand interviews with key actors of the Special Rapporteurs. It also offers qualitative information, which is not always obtainable through state agencies. This addresses another challenge pointed out by Anna Würth:

Many institutions insist on using quantitative data, to prevent subjective factors from influencing the evaluation of data. Important as this is, it also seems overly ambitious, given the limited availability of data. At the same time, it also seems to underestimate the relevance of qualitative data. Subjective experiences of, e.g. freedom, well-being, and security, are tremendously important for understanding social movements, state repression techniques and, more generally, a human rights situation (Würth 2006: 81).

The standard-centered approach also makes it possible to dump the results of empirical analysis into a “Yes/No” binary matrix that measures whether there is compliance with international standards. This matrix may allow diachronic comparisons (analyzing, for instance, the performance of a state over time) or synchronous comparisons (analyzing the performance of different national states). By enabling the comparison of different dimensions of a right, this binary matrix can also offer a “road map” for identifying a state’s greatest deficiencies and establishing priorities on public policy recommendations. Another advantage of the standard-centered approach is that it permits a narrower, more focused view of international and regional standards. In this sense it allows for adaptation to each context and it guarantees coherence within the regional legal framework.

The human rights based approach and the standard-centered approach are closely related and should be seen as complementary methodologies. The combination of both should permit state accountability to an external control source. As we will see in the following section, each approach offers valuable information about other aspects of the same human right.

Empirical Section: Use and Abuse of Public Advertising in Mexico

After describing three different methodological approaches to the elaboration of human rights indicators, in this section we will apply them when elaborating different indicators of public advertising in Mexico. As we will see, each methodology will allow us to shed light on different aspects of the same phenomenon.

Budget Analysis

In order to apply the budget analysis approach, we will take as reference the expenditure of the Mexican government on public advertising between 2013 and 2017, published in an online government platform6 and systematized in a report by the NGO Fundar (2017). The study compares the expenditure on public advertising by campaign, type of medium, supplier and government agency, among other categories. This allows us to understand what kind of indicators we can elaborate with an approach like budget analysis7.

The first relevant information offered by this platform is the governtment’s yearly expenditure on public advertising, which ranged from MXN 8.154 million (about USD 627 million) in 2013 to MXN 10,698 million (about USD 510 million) in 2016. These figures allow us to measure the money that the government invests in promoting its actions and contrasting it with expenditure in other relevant programs. This way, it is possible to analyze whether the government is respecting the maximum use of available resources to fulfill human rights. According to the same report, this amount is similar to the yearly expenditure on the whole Rural Productivity Program or on postgraduate scholarships and support to quality projects that benefit over 57.000 people (Fundar 2017: 7).

Yearly expenditures allow us also to make international comparisons and give us excellent information to establish expenditure ceilings to public advertisement. A comparative analysis by Espada and Marino (2020) with figures from 2017 and 2018 reveals that the yearly budget for public advertising in Mexico was of about USD 476 millions, far above Brazil’s budget (USD 100 millions), Argentina (USD 76 millions), Bolivia (USD 75 millions), Ecuador (USD 52 millions), Chile (USD 42 millions) or Spain (USD 23 millions). Mexican expenditure is also very high if we calculate it per-capita (PC), with 3.82 U$ PC, far above from Chile (2.27 U$ PC), Argentina (1.71 US PC), Peru (1.17 U$ PC), Spain (0.51 U$ PC) or Brazil (0.48 U$ PC), and is surpassed in the region only by Bolivia (U$ 6.7 PC).

It is noteworthy that the recently elected president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador reduced the expenditure in public advertising in 2019 to about USD 205 million and committed to spending less than 0.1 % of the national budget in public advertising.

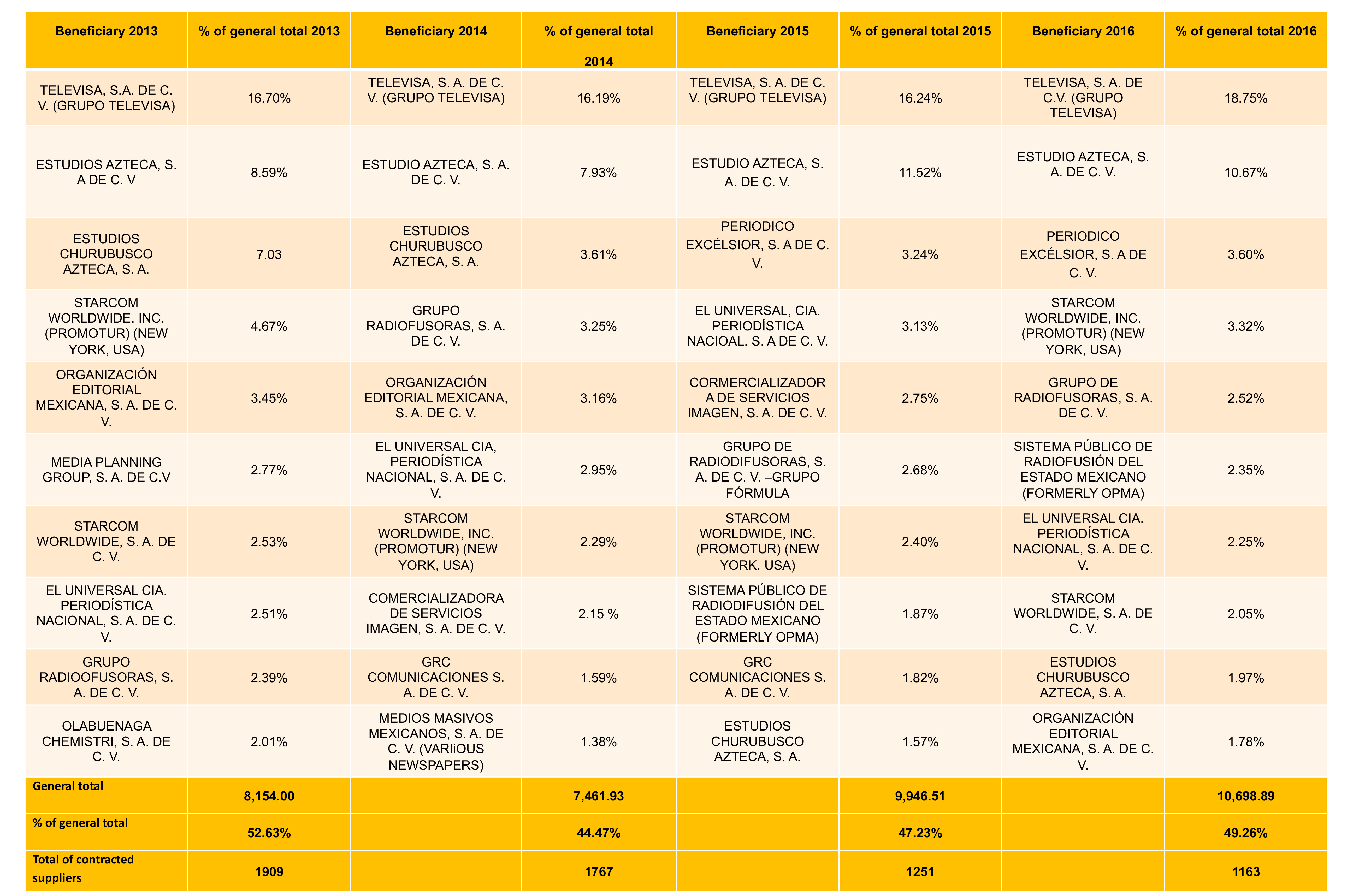

The budgetary information provided by the Mexican government also shows the proportion of public advertisement received by each supplier. This information allows us to construct indicators on the concentration of public advertising. In this same report, we can see that between 2013 and 2016 there was a concentration of almost 50% of the total amount going towards the first 10 suppliers, with a clear predominance of the TV channels Televisa and TV Azteca (Fundar 2017:12).

The concentration of public advertisement in a few hands is one of the central concerns of Fundar (2017) and of other organizations that analyze public advertisement in the rest of Latin America (ADC 2005, ADC 2010). However, this issue does not receive particular attention in the UN Media Development Indicators, nor in the Inter-American standards on official advertising. This shows us how each methodology sheds light on different phenomena and how they complement each other.

The UN Indicators System

When applying the UN indicators system, we have the great advantage of the systematization effort carried out by the United Nations in recent years in relation to media, synthesized in the publication “Media Development Indicators” (2008). As the report states in its introductory words: “This document builds on an earlier analysis of existing initiatives to measure media development that employed a diverse range of methodologies (…). This document does not prescribe a steady methodological approach, but prefers a ‘toolbox’ approach in which the indicators can be adapted to the particularities of the national context” (UNESCO 2008: 5). Nevertheless, the report represents the biggest systematization effort in the field of media indicators and it is a very valuable tool for our analysis.

In this publication, UNESCO describes the main issues related to official advertising in the following terms: The placement of government advertising can also inhibit or encourage media pluralism and development. It is beyond the scope of this section to look in detail at regulation concerning advertising content. State-funded advertising may be a crucial source of revenue in countries with a poorly developed commercial advertising market. The principle of non-discrimination is key: the state should not use advertising as a tool to favour certain media outlets over others, for either political or commercial gain. Nor should public broadcasters gain an unfair advantage over their commercial rivals by offering advertising at below market rates (…). The state may restrict the overall amount of advertising in the interests of programme quality; however, limits should not be so strict as to stifle the growth of the media sector, nor should one sector of the media be unfairly disadvantaged. Regionally agreed limits may act as a guide e.g. the European Convention on Transfrontier Television (UNESCO 2008: 47).

We can extract some key principles and criteria for the monitoring of public advertising from these two paragraphs: A) The principle of non-discrimination for political or economic reasons; B) The regulation of possible unfair advantages of public broadcasters over their commercial rivals; C) The role of official advertising when promoting (independent and high quality) media; D) Some criteria for setting floors and caps to the amount of public advertising, for example, that it should not be so low as to stifle the growth of media; E) It also includes a reference to the European Convention on Transfrontier Television, mainly oriented to the clear separation of advertising and content 8. Based on these principles, UNESCO proposes the following indicators:

The state does not discriminate through advertising policy

The state places advertising in a fair, transparent and non-discriminatory manner e.g. through a code of conduct.

Allocation of government advertising is strictly monitored to ensure fair access by all media.

Public service broadcasters are subject to fair competition rules in regards to the advertising they carry.

Codes of conduct or other guidelines for the allocation of state-funded advertising implementation.

Effective regulation governing advertising in the media

Broadcasters and print media adhere to nationally or regionally agreed upon limits on advertising content, where applicable.

Broadcasters and print media adhere to nationally or regionally agreed upon guidelines for the separation of advertising and programming, where applicable.

Existence of a code of advertising, established by an independent professional body, to prevent misleading advertising.

After establishing the indicators, the next step is to find suitable sources for empirical research. UNESCO’s report cites a series of reports and webpages, mainly related to the European and African context. This material provides valuable references for the elaboration of indicators, but not for empirical analysis9. For the empirical comparison of indicators, the report refers to the following two means of verification: A) the existence and implementation of a code of advertising and B) the existence and implementation of “Guidelines for amount of advertising content and separation of advertising and programming”.

Since most of the Media Development Indicators refer to the structural realization of the right, we can use the Mexican legislation and institutional structure as a reference. But we should also analyze the way the code of advertising and the mentioned guidelines are being implemented under the means of verification. As we will see in the following section, the reports of the Special Rapporteurs on Freedom of Expression offer valuable information for examining the implementation of the advertising code and guidelines while also providing us many elements for the analysis of procedural and result indicators.

The Standard-Centered Approach

In order to apply the standard-centered approach, we will take as a reference a fragment of our research project “Freedom of Expression in Mexico: A Proposal for Evaluating Public Policies on Freedom of Expression from a Human Rights Perspective”, where we elaborate indicators based on the Inter-American standards on official advertising and contrast them with the reports of the United Nations Rapporteurs for Freedom of Expression and the Organization of American States. In this project we identified the following indicators on public advertising:

There is a specific legal framework that regulates public advertising. It contains clear rules regarding its objectives, allocation criteria and procedures for its application (IACHR 2012:25).

After their visit to Mexico in 2010, the UN and OAS Special Rapporteurs for Freedom of Expression recommended the adoption of a legal framework to regulate public advertising. Eight years later the General Law of Social Communication was approved, as a result of the pressure of civil society and international organizations. During their visit in 2018, the Rapporteurs expressed their doubts regarding the new legal framework in the following terms: “Proposed legislation to regulate official advertising was introduced in Congress in March 2018, following a landmark ruling by the Supreme Court. In a fast-track process the Senate passed the proposed legislation, later signed into law by the President on 11 May 2018, without any changes (…). The Special Rapporteurs are concerned that the new legislation fails to meet basic principles and recommendations of international human rights bodies and experts” (UN /IACHR 2018a: par. 65-66). In a press release they also declared: “We are concerned the proposed law continues to leave a wide margin of discretion to government officials to establish criteria for the allocation and use of Government funds for advertising” (UN /IACHR 2018b).

Result: intermediate

Public advertising transmits clear information, does not cause confusion or induce mistakes or preferences for any political orientation (IACHR 2012:21).

The Mexican Constitution (Art. 41 and 134) and the General Law of Social Communication (Art. 9), prohibits explicitly political promotion. Nevertheless, NGOs like Fundar or Article XIX have denounced for many years: “The use of resources destined to social communication as a tool for self-promotion, propaganda or to publicize actions and programs that legitimize the actions of government agencies” (Fundar/Article 19: 2009). After reading the draft of the new General Law on Social Communication in 2018, the Special Rapporteurs also expressed some doubts regarding this issue: “The law should clearly prohibit the use of government advertising for electoral or partisan purposes…” (UN/IACHR 2018b).

Result: intermediate

An autonomous body monitors the allocation of state-funded advertising, guarantees equal access to media to resources, supervises the campaign planning process and is entitled to carry out periodic audits.

Mexico does not have an autonomous monitoring body. The above-mentioned tasks are performed by administrative units that are part of public agencies, in accordance with articles 5, 20, 37 and 42 of the General Law of Social Communication. Political advertising during electoral processes is the only exception. These are regulated by an autonomous body, the National Electoral Institute. In April 2019 the Special Rapporteur of the OAS, Edison Lanza, declared in an interview: “This relationship between political power and the press is scandalous (…). It would be good if (President) López Obrador did not only reduce official advertising; it is also desirable that he establishes objective rules through an independent external body which can oversee how advertising is allocated. That relationship would start to change with good legislation that meets international standards” (Proceso 2019).

Result: negative

The legal framework contemplates sanctions (or negative consequences) for non-compliance.

According to the IACHR, “States must establish certain negative consequences for non-compliance with obligations foreseen in a norm that regulates official advertising. In the first place, they should actively promote the alignment of their practices with recommendations made by audits. Secondly, non-compliance must be punished appropriately and proportionally to the fault committed” (OAS-IACHR 2012). Nevertheless, the Mexican legal framework does not contemplate sanctions. It only includes a list of actions that are considered prohibited. This limitation was pointed out by the Special Rapporteurs on a press release, where they declared that: “…the law should provide for accountability procedures, backed by penalties and appropriate remedies” (UN/IACHR 2018b).

Result: negative

There is a fair, transparent and non-discriminatory procedure in the contracting and distribution of official advertising. All the stages of this process are fully public and the procedure contemplates the right to reply.

In its 2011 annual report, the IACHR contains a chapter dedicated to the “Principles on Regulation of Official Advertising in the Inter-American System for the Protection of Human Rights”. The report critiques the decision of the para-state oil company PEMEX to withdraw official advertising from the political magazine Contralínea, as a result of its investigation of a corruption case within the aforementioned company. As brought up by the arguments of the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH), the report points out that it is necessary for the state company “to have objective, clear, transparent and non-discriminatory procedures and criteria for the granting and distribution of official advertising in favor of different means of communication, both electronic and printed” (IACHR 2012: Par. 15). In 2018, shortly after the new legal framework came into effect, the Special Rapporteurs pointed out that: “the law does not establish clear rules regarding its objectives, allocation criteria and procedures, and oversight mechanisms, leaving a wide margin for Government discretion and abuse. The IACHR’s report `Guiding Principles on the Regulation of Government Advertising and Freedom of Expression` (2012) finds that the establishment of specific, clear, and precise laws is essential to prevent abuse and excessive spending. The Special Rapporteurs call on the Mexican Government to amend the legislation, according to these principles and best practices” (UN/IACHR 2018a).

Result: negative

The state provides a clear, written explanation of the parameters used for the allocation of public advertising and uses as its main criteria a campaign’s audience profile, in addition to others such as the size of circulation or audience and campaign prices.

The “Principles on the Regulation of Government Advertising and Freedom of Expression” (IACHR 2012) specify that “Campaigns must be decided upon based on clear, public allocation criteria established prior to the advertising decision. At the time of placing the ad, the State must provide a clear, written explanation of the parameters used, and the manner in which they were applied (…). Government advertising should be oriented toward the effectiveness of the message. In other words, the message should be received by the audience that the campaign seeks to reach. The target population determines the range of eligible media; then, among other variables, the State must consider the size of the circulation or audience—which should be broad and comprehensive—and the price, which must never exceed the price paid by a private advertiser (IACHR 2012: par. 51-53). As this statement by the Special Rapporteurs shows, Mexico’s new legal framework does not meet this requirement. “The Special Rapporteurs are concerned that the new legislation fails to meet basic principles and recommendations of international human rights bodies and experts. In particular, the law does not establish clear rules regarding its objectives, allocation criteria and procedures, and oversight mechanisms, leaving a wide margin for Government discretion and abuse (UN/IACHR 2018a: par. 66).

Result: negative

Conclusions: An Integrated List and some Reflections on the Different Approaches when Elaborating Indicators

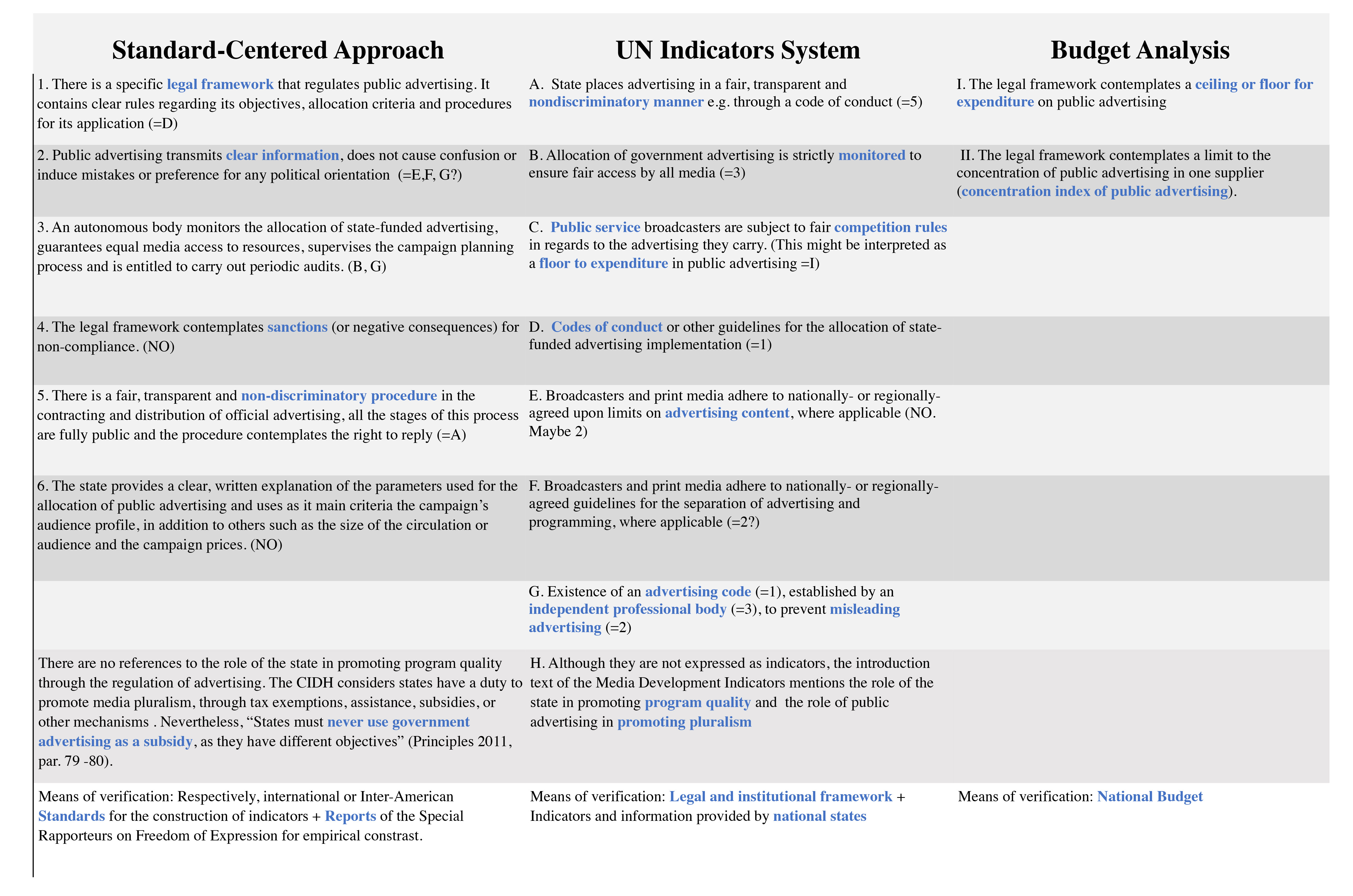

Having applied the three methodological approaches to the case of public advertising, we are now interested in drawing some general conclusions. We will start by comparing the indicators elaborated with each approach and analyze the complementarity and consistency between them.

As the following table shows, there are many coincidences (marked in green), specially between the Media Development Indicators and the ones elaborated with the standard-centered approach. However, some indicators are not mentioned or are referred to very tangentially in the other two approaches and in some cases, there is even disagreement among the criteria (marked in red).

If we combine the different approaches, we could have the following results:

There is a specific legal framework that regulates public advertising. It contains clear rules regarding its objectives, allocation criteria and procedures for its application.

Public advertising does not lead to misinformation, it transmits clear information, does not cause confusion or induce mistakes or preference for any political orientation. There is a clear separation between program content and advertising.

An autonomous body monitors the allocation of state-funded advertising, guarantees media equal access to resources, supervises the campaign planning process and is entitled to carry out periodic audits.

The legal framework contemplates proportional sanctions for non-compliance.

There is a fair, transparent and non-discriminatory procedure in the contracting and distribution of official advertising, all the stages of this process are fully public and the procedure contemplates right to reply.

The state provides a clear, written explanation of the parameters used for the allocation of public advertising and follows as its main criteria the campaign’s audience profile, in addition to others such as size of circulation or audience and campaign prices.

The legal framework contemplates a ceiling or floor to expenditure on public advertising.

The legal framework contemplates a limit for the concentration of public advertising in one supplier (concentration index of public advertising).

Source: Own elaboration

Figure 3: Comparison of the Indicators Constructed with each Methodological Approach

The indicators on limits to advertising content or related to the role of public advertising to promote media pluralism, should be included in a way that they do not collide with the Inter-American standards.

Having defined the list of official advertising indicators, we would like to close with some general reflections regarding the three methodological approaches.

In the first place, we can observe that each approach refers to different sources. The source of analysis in the budget approach is the national budget. The Media Development Indicators referred mainly to structural data, such as the legal and institutional framework. They also refer to the implementation of these frameworks, but there is no explicit reference to the sources to analyze them. This problem was already foreseen when the Media Development Indicators were written. In the introduction, the authors point out that: “Data is scarce at a global level, and therefore this document, by itself, will not be able to provide all the information required to apply its approach as a diagnostic tool. More work to identify the required data to measure the suggested indicators is needed. It may be useful to draw on the experiences of other fields to establish reliable sources of national data” (UNESCO 2008:6). The standard-centered approach, on the other side, is based on the international (or Inter-American) standards and the reports of the Special Rapporteurs on Freedom of Expression. In this sense, the standard-centered approach has the advantage of combining a vast and coherent source for the construction of indicators (the standards) with a detailed source for empirical contrast (the reports). The reports of the Special Rapporteurs also offer a valuable source in those cases where there is no official information or the available information is not trustworthy, as pointed out in the introduction of the Media Development Indicators (UNESCO 2008:6).

Secondly, we observe that the most detailed process indicators are those elaborated with the standard-based approach. For their part, the Media Development Indicators are very valuable when elaborating structural indicators related to the legal and institutional framework of public advertising. By providing information on how resources were finally spent, budget analysis offers great outcome indicators. We do not intend to draw any general conclusions from this statement. However, in this case we do find a correlation between the three approaches and the three types of indicators used by the United Nations.

Finally, each approach offers input to analyze other aspects of the same phenomenon. The reason for that is probably that each approach starts from different initial premises and concerns. From the perspective of the Media Development Indicators, there is a strong drive to regulate misleading advertising and to ensure that states provide enough resources to contribute to the sustainability of media. This last concern is very relevant in the African context, as we point out in footnote number 8. Nevertheless, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) seems more preoccupied with state control over media, than with media sustainability. That is why the Inter-American standards explicitly discourage the use of public advertising as a subsidy. Budget analysis - based on the work of Fundar, a social organization deeply rooted in Mexican issues- guides its efforts towards avoiding the concentration of public advertising in a few hands and limiting the total amount of official advertising, two issues of enormous relevance in the Mexican context. Finally, the Inter-American standards were based on the on-site experience of the Special Rapporteurs and on the efforts of a group of social organizations led by the Civil Rights Association (ADC), which requested a hearing with the IACHR to address this issue (ADC 2005). Perhaps for this reason, this approach is concerned with regulating in detail the processes through which the budget for public advertising is manipulated in the region (e.g. use of objective parameters for the allocation of advertising, existence of penalties for non-compliance, characteristics and functions of the monitoring body) and offers very valuable indicators for understanding and monitoring the allocation of public advertising with a local perspective.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)