Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is known as a syndrome characterized basically by an inappropriate function in emptying and/or filling of ventricular cardiac chambers which leads to a circulatory deficit to cover the metabolic and energetic demands of the body1,2. This disease shows a wide range in its clinical presentation, from a completely asymptomatic subject to the group of patients unable to perform physical activity; in advanced stages, it may reach pulmonary edema and cardiogenic shock. Causing, throughout the clinical horizon of this pathology, some degree of decline in quality of life (QoL), an economic impact on the individual, family life and health institutions responsible for the care of the population3, as well as a significant decrease in life expectancy with high mortality4 and high rates of hospital admissions5,6.

Notably, HF is a very important public health problem worldwide, as population studies have reported that 1-2% world population suffers from this disease7,8 and one of five people over 40 will experience it at some point in their life9; after the eighth decade of life, the prevalence increases to 11.6%6,8,10. This pandemic causes great demand for health care, generating up to 46.1% of cardiovascular readmissions in the emergency rooms of general hospitals11. HF is known to have an unfavorable prognosis when it has reached the symptomatic phase7; about 60% of patients with this diagnosis die within the first 5 years of clinical follow-up12, and this figure increases to 90% when severe HF has been diagnosed7.

In the past decades, pharmacological therapeutic breakthroughs have allowed a decrease in the clinical, social, and economic impact of this disease13 that is why the importance of optimal medical treatment is stressed, which should be reflected in clinical stabilization, improvement in QoL, a decrease in hospital admissions, as well as, by postponing the time to specialized management, consisting in electrical resynchronization therapy, surgical alternatives, and even heart transplant.

Any efforts to achieve a clinical improvement in patients will be of utmost importance since this pathology has an impact on the economy of national and global health systems, as well as on people, family, and work level, causing great man-hour loss7, in addition to high admission and readmission rates3,5,7,14.

For this reason, there is a need to form a multidisciplinary group constituted in specialized centers for the care of the HF in the different hospital levels, where comprehensive care based on scientific evidence is provided, with therapeutic management guided by national and international standards, as well as continuing medical education to the patient and the caregivers involved. Always aiming to improve the quality in the diagnosis, management, and monitoring of this disease; without excluding promoting research in this area.

Remarkable advances in pharmacological therapeutics have increased survival in the general population; the well-known form of the population pyramid has tended toward reversing with an increase in the proportion of older adults. Pathologies previously considered to have a high mortality, such as various types of cancer or myocardial infarction, with the advent of new therapies have reduced their fatality rates15. Thus, it is recognized that the use of radiotherapy and chemotherapy (e.g., alkylating agents, anthracyclines, and HER-2 targeted therapies) conditions diastolic dysfunction and myocardial fibrosis16; in addition, cardiovascular disease survivors (e.g., congenital, valvular, and ischemic) will achieve a better long-term survival. In addition to these prognostic advances, the provision of life expectancies in the general population increases the risk, probability of presentation, and prevalence of HF in the following decades.

Minimal reports and clinical descriptions for this pathology have been published in Mexico, so the work of the National Institute of Cardiology HF Center (Centro en Insuficiencia Cardiaca del Instituto Nacional de Cardiología) is needed to describe, analyze, investigate, and disclose the statistical, epidemiological, demographic, and clinical data related to this disease, as well as continuous training of multidisciplinary staff (including nurses, psychologists, rehabilitators, nutritionists, social workers, and physicians) to face the effects of this disease in the future.

Given the magnitude of epidemiological evidence and the demand for a specialized service for this condition, in the 90s, Dr. Gustavo Sánchez Torres organized the patients with this pathology. In 1999, the initiative of Dr. Ignacio Chávez Rivera could accomplish the Department of HF and Heart Transplants. Initially, this division was aligned under the leadership of Dr. Sergio Olvera Cruz and Dr. Arturo Méndez, to be later lead by Dr. Gerardo López Mora; since September 13, 2016, the HF Center (CEIC) of the National Institute of Cardiology has been led by Dr. Eduardo Chuquiure Valenzuela and Dr. Oscar Fiscal Lopez.

This research is intended to initially report the demographic, etiological, and clinical data of 300 patients, to generate a situational diagnosis of the HF problem in Mexico.

Materials and methods

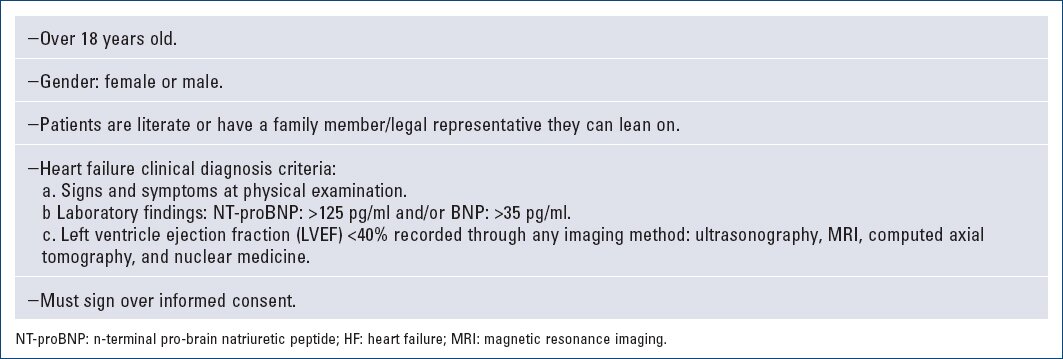

We initially analyzed the clinical characteristics of 300 patients whom we evaluated at the National Institute of Cardiology HF Center. Patients older than 18 years with a diagnosis of HF were consecutively included, according to the clinical criteria of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)17 and the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA)18. We obtained both clinical and medical variables.

The patients agreed to the use of all their data, exclusively for the purposes of this research. The Institutional Ethics Committee approved this research. The patients were approached by trained personnel (nurses, psychologists, and physicians), and subsequently, they underwent: comprehensive clinical review, demographic survey, and review of laboratory test and imaging. We administered pharmacological treatment according to guidelines17,18. Medical education was provided, patient and relative doubts were resolved, and clinical follow-up was planned.

We obtained the collection and systematization of the information through an electronic tool of the Google Drive platform. We analyzed 292 variables classified into five dimensions: (a) general characteristics, (b) clinical backgrounds, (c) laboratory and imaging studies, (d) therapeutics, and (e) risk and follow-up. For the statistical analysis, we used the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences SPSS-22; the description of the density of the continuous variables expressed as mean and standard deviation states a level of significance to avoid alpha error less 0.05.

Results

Data were collected from October 1, 2016, to January 31, 2017. For this report, we included consecutively the first 300 patients, 8 of whom were dismissed (4 minors and 4 who did not meet HF clinical criteria); finally, we defined our study group of 292 patients (Fig. 1). Mean age observed was 56.7 +- 14.3 years (range 18-86). Only 8.90% of patients were older than 75 years. The sex ratio was 205 males (70.2%) and 87 females (29.8%), 10.2% of males and 5.8% of females were older than 75 years. The mean weight was 73.9 +- 14.6 Kg (35.4-130 Kg), mean height 162 +- 9 cm (137-192 cm), and for a body mass index (BMI) of 28 +- 4.5 Kg/m2 (16.6-43.6 Kg/m2). We determined that 31.1% of patients had a BMI > 30 Kg/m2, being the obesity indicator in the population. The mean abdominal circumference was 92.4 +- 6.7 cm (44.5-154 cm), 93.8% had a waist circumference >90 cm. 96.3% of patients were in NYHA functional Classes I and II and the remaining 3.7% in Classes III and IV (Table 1).

Table 1 Demographic data

| Demographic | Mean +- SD (Range) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 56.7 +- 14.3 (18-86) |

| Weight (Kg) | 73.9 +- 14.6 (35.4-130) |

| Height (cm) | 162 +- 9.2 (137-192) |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 28 +- 4.5 (16.6-43.6) |

| Abdominal circumference (cm) | 92.4 +- 6.7 (44.5-154) |

| Demographic | n (%) |

| Gender | 205 men (70.2) 87 women (29.8) |

| NYHA functional class | |

| I | 77 (26.4) |

| II | 204 (69.9) |

| III | 10 (3.4) |

| IV | 1 (0.3) |

SD: standard deviation, Kg: kilograms, cm: centimeters, BMI: body mass index

n: number, NYHA: New York Heart Association.

Clinical data

The distribution by etiology was made up of 98 patients (33.6%) with ischemic heart disease, followed by 68 (23.3%) idiopathic etiology, 66 (22.6%) hypertensive heart disease, and 32 (10.9%) valvular diseases. We classified 28 patients (9.6%) under "other" several etiologies, of which: 7 (2.4%) correspond to congenital heart diseases, 5 (1.7%) secondary to cancer/chemotherapy, 4 (1.4%) associated to myocarditis, 3 patients (1%) secondary to Chagas' disease, 3 females (1%) with HF associated to pregnancy, 3 patients (1%) with non-compaction cardiomyopathy, 2 (0.7%) with cardiac amyloidosis, and one patient with Takayasu's disease (Table 2).

Table 2 Etiology of disease

| Etiology | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Ischemic | 98 (33.6) |

| Idiopathic | 68 (23.3) |

| Hypertension | 66 (22.6) |

| Valvular | 32 (10.9) |

| Others | 28 (9.6) |

n: number.

The most prevalent clinical histories were as follows: 107 patients (36.7%) with systemic hypertension, 77 (26.4%) with a history of myocardial infarction, 44 (15.1%) with dyslipidemia, 91 (31.2%) were diabetic, 77 (26.4%) with a smoking history, 3 patients (1%) were current smokers, 32 (11%) had a history of angioplasty, and 12 (4%) bypass surgery history. In addition, sudden death, ventricular fibrillation, or ventricular tachycardia were observed in 10 patients (3.4%), thyroid disease in 9 (3.1%), alcoholism history in 8 (2.7%), chronic kidney disease in 8 (2.7%), 4 (1.3%) under dialysis therapy, 4 (1.4%) with a history of stroke, and finally, anemia in 3 subjects (1%) (Table 3).

Table 3 Description of clinical risk factors

| Background | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Hypertension | 107 (36.7) |

| Myocardial infarction | 77 (26.4) |

| Dyslipidemia | 44 (15.1) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 91 (31.2) |

| Previous smoker | 77 (26.4) |

| PTCA/stent | 32 (11) |

| CABG | 12 (4.0) |

| VT/VF/sudden death | 10 (3.4) |

| Thyroid disease | 9 (3.1) |

| Alcoholism | 8 (2.7) |

| Renal disease | 8 (2.7) |

| Dialysis | 4 (1.4) |

| CVA/TIA | 4 (1.4) |

| Anemia | 3 (1.0) |

| Current smoker | 3 (1.0) |

PTCA: percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; VT: ventricular tachycardia; VF: ventricular fibrillation; CVA: cerebrovascular accident; TIA: transient ischemic attack.

Concerning respiratory symptoms, dyspnea showed the highest prevalence, its variant at rest was observed in 25 patients (8.6%), exertion associated in 121 (41.4%), orthopnea in 27 (9.2%), and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea only in 12 (4.1%). In addition, 6 patients (2.1%) experienced palpitations, 21 (7.2%) dizziness/syncope, fatigue was present in 64 patients (21.9%), loss of appetite in 6 (2.1%), changes in weight such as increase in 7 (2.5%) patients and decrease in 1 (0.3%), tachypnea in 3 (1%), and oliguria in 2 (0.7%) (Table 4).

Table 4 Clinical symptoms

| Symptoms | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Exertional dyspnea | 121 (41.4) |

| Dyspnea at rest | 25 (8.6) |

| Orthopnea | 27 (9.2) |

| Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea | 12 (4.1) |

| Palpitations | 6 (2.1) |

| Dizziness/syncope | 21 (7.2) |

| Fatigue | 64 (21.9) |

| Loss of appetite | 6 (2.1) |

| Weight gain | 7 (2.5) |

| Weight loss | 1 (0.3) |

| Tachypnea | 3 (1.0) |

n: number.

Regarding clinical signs of fluid overload, lower limb edema occurred in 21 patients (7.2%), as well as ascites in 3 (1%). On the other hand, murmurs were auscultated in 26 patients (8.9%) and third heart sound (S3) in 15 (5.1%). Furthermore, only 46 (15.8%) patients with hepatojugular reflux and 12 (4.1%) with hepatomegaly on palpation. Of total patients, only 6 (2.1%) presented lung rales on auscultation (Table 5).

Table 5 Clinical signs

| Clinical signs | n (average) |

|---|---|

| Edema | 21 (7.2) |

| Ascites | 3 (1.0) |

| Murmur | 26 (8.9) |

| S3 heart sound | 15 (5.1) |

| Displaced apex beat | 4 (1.4) |

| Jugular ingurgitation | 95 (32.5) |

| Hepatojugular reflux | 46 (15.8) |

| Hepatomegaly | 12 (4.1) |

| Cold extremities | 10 (34) |

| Pulmonary rales | 6 (2.1) |

| Pleural effusion | 3 (1.0) |

n: number.

Mean systolic blood pressure was 121.6 +- 11.9 mmHg (range 75-171 mmHg), we measured 0.7% with values less 90 mmHg and 8.9% with values >140 mmHg. Mean diastolic blood pressure was 71.2 +- 7.7 mmHg (range 45-106 mmHg), only in 1% it was less 50 mmHg and in 3.1% >90 mmHg. Mean heart rate was 68.7 +- 11.9 beats per minute (bpm) (43-226 bpm), being >75 bpm in 11% of our population; a patient presented with atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. Mean respiratory rate was 14 +- 1.1 bpm (10-18 bpm); capillary oxygen saturation was 92.9 +- 3.1% (63-99%). Only 5.8% patients with capillary saturation less 91% (Table 6).

Table 6 Vital signs

| Clinical sign | Mean +- SD (range) |

|---|---|

| Systolic pressure (mmHg) | 121.6 +- 11.9 (75-171) |

| Diastolic pressure (mmHg) | 71.2 +- 7.7 (45-106) |

| HR (bpm) | 68.7 +- 11.9 (43-226) |

| Respiratory rate (bpm) | 14 +- 1.1 (10-18) |

| Oxygen saturation (%) | 92.9 +- 3.2 (63-99) |

SD: standard deviation; mmHg: millimeter of mercury; HR bpm: beats per minute; bpm: breaths per minute; HR: heart rate.

Laboratory and imaging studies

Laboratory blood test levels were as follows: mean hemoglobin (Hb) 14.3 +- 2.1 gr/dL (10-20.1), lymphocytes count 2.1 +- 0.8/mm3 (0.3-4.7), serum glucose 116.4 +- 4.3 mg/dL (69-286), glycated Hb 7.2 +- 1.9% (5.1-11.5), serum creatinine 1.2 +- 0.6 mg/dL (0.5-5.2), blood urea nitrogen 26.9 +- 18.1 mg/dL (8.2-109.2), serum albumin 4.1 +- 0.5 g/dL (2.3-5.2), uric acid 6.5 +- 1.9 mg/dL (3.1-14.7), serum sodium 138 +- 3.2 mEq/L (128-144), serum potassium 4.5 +- 0.5 mEq/L (3.3-6.2), total cholesterol 154.3 +- 4.3 mg/dL (71.7-291), triglycerides 158.4 +- 127.2 mg/dL (25.6-1032.2), high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol 36.9 +- 1.4 mg/dL (19.9-61.8), and low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol 98.5 +- 44.9 mg/dL (28.9-213). Mean n-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide level was 517.2 +- 157.8 pg/ml (383-1372) (Table 7).

Table 7 Serum laboratory studies for patients with HF

| Parameter | Mean +- SD (range) |

|---|---|

| Hb (gr/dL) | 14.3 +- 2.1 (10-20.1) |

| Lymphocyte (mm3) | 2.1 +- 0.8 (0.3-4.7) |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 116.4 +- 4.3 (69-286) |

| Glycosylated Hb (%) | 7.2 +- 1.9 (5.1-11.5) |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 26.9 +- 18.1 (8.2-109.2) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.2 +- 0.6 (0.5-5.2) |

| Albumin (gr/dL) | 4.1 +- 0.5 (2.3-5.2) |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 6.5 +- 1.9 (3.1-14.7) |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 517.2 +- 157.8 (383-1372) |

| Serum sodium (mEq/L) | 138.0 +- 3.2 (128.0-144.0) |

| Serum potassium (mEq/L) | 4.5 +- 0.5 (3.3-6.2) |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 154.3 +- 4.3 (71.7-291) |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 36.9 +- 1.4 (19.9-61.80) |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 98.5 +- 44.9 (28.9-213) |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 158.4 +- 127.2 (25.6-1032.2) |

SD: standard deviation; NT-proBNP: n-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; Hb: hemoglobin; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; LDL: low-density lipoprotein.

From the electrocardiographic (EKG) parameters, we determined that 248 patients (84.9%) were in sinus rhythm, 15 (5.1%) in atrial fibrillation rhythm, pacemaker rhythm 27 (9.2%), and in two (0.7%), there was no EKG at the time of data collection. Discarding patients with a pacemaker and the two patients without an EKG, we observed that the average QRS duration was 127.2 +- 30.3 ms (80-240 ms). 13.7% of patients showed that a QRS was >130 ms. 7.5% of patients showed complete left bundle branch block. We observed 58 patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillator/cardiac resynchronization therapy (19.9%) (Table 8).

Table 8 EKG parameters

| Parameter | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sinus rhythm | 248 (84.9) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 15 (5.1) |

| Pacemaker rhythm | 27 (9.2) |

| Bundle block | 22 (7.5) |

| QRS over 130 ms | 40 (13.7) |

| ICD/CRT | 58 (19.9) |

SD: standard deviation; ICD: implantable cardioverter defibrillator; CRT: cardiac resynchronization therapy.

Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was quantified in all patients; the prevalent method was electrocardiogram performed in 283 patients (96.9%). In the remaining patients, it was obtained using other methods such as magnetic resonance imaging, computerized tomography, or scintiscan. We observed a mean LVEF 29.2 +- 10.6% (range 9-73); 223 patients (86.6%) classified as HF with reduced LVEF. Mean left ventricular diastolic diameter measure was 57.6 +- 5.4 mm (35-86) and left ventricular systolic diameter 46.9 +- 5.3 (23-71); mean measurement of interventricular septum was 9.2 +- 1.4 mm (8-14) (Table 9).

Table 9 Echocardiogram parameters

| Parameter | Mean +- SD (Range) |

|---|---|

| LVEF % | 29.2 +- 10.6 (9-73) |

| LV diastolic diameter mm | 57.6 +- 5.4 (35-86) |

| LV systolic diameter mm | 46.9 +- 5.3 (23-71) |

| Interventricular septum mm | 9.2 +- 1.4 (8-14) |

SD: standard deviation; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; LV: left ventricle; mm: millimeter.

Medical treatment

The percentage of patients receiving treatment with ACEIs or ARB II was 65.7%; the most common was enalapril, 71.9% of patients received 10 mg every 12 h. The most common adverse effect observed was persistent cough. 68.4% was under treatment with beta-blocking (BB) agents. We observed intake of tartrate, so we provided medical education and change of BB. The most commonly used corticoid-blocking agent was spironolactone (79.5%), at a dose of 25 mg/day. In addition, furosemide 40 mg/day, the dose most commonly indicated in 69.2% of patients. Ivabradine was administered to 5.5% of patients in this study at a dose of 5 mg every 12 h. ARNI is used in 9.6% of patients, observing as main adverse effect associated low blood pressure. Only 14% of patients took digitalis orally.

Discussion

The institute is a national hospital where patients from all states in our country are treated; thus, this report summarizes the clinical situation of patients over 18 years of age with HF diagnosis in Mexico. Of the samples collected, four pediatric patients were not included; we believe that this population at risk should also be assessed within a center specialized in HF. Another four subjects did not meet the diagnostic criteria. Importantly, data collection was carried out at the HF Center of the National Institute of Cardiology "Ignacio Chávez."

It is important to highlight that in this report of Mexican patients, HF presentation is observed a decade before compared to other population groups, as the mean age of our patients was 57 years, which is under 72.90 years (2002) and 72.27 years (2013), reported in the US National HF Cohort:21 The Netherlands reported 71.2-72.9 years in males and 75-77.7 years in females22. In the MAGGIC meta-analysis, which included 41,972 patients from 31 clinical trials, the mean age was 68 years23. This early presentation might be mediated by the impact of obesity and diabetes mellitus in Mexico, factors that increase the risk of HF, as well as the consequences it involves24.

Moreover, a greater proportion of male patients older than 75 years was observed, as compared to the AHA report where they specify that since 2013 in the American population over 80 years of age represents 83% of male and 87.1% of female cardiovascular patients18. Obesity in Mexico is a public health problem, the National Survey of Health and Nutrition (ENSANUT) reported a 76.6% obesity rate in adults over 20 years of age, this differs with the study population25.

The main HF-related etiology in this population is ischemic, concomitantly with reports from other population groups26, followed by arterial hypertension. In our population, valvular heart disease was found to be important compared to other population groups; other etiologies are infectious not only myocarditis but also Chagas' disease. Takayasu's disease as an HF-associated etiology draws our attention27.

Other associated etiological pathologies to be considered in the future, for their association with myocardial damage, are congenital abnormalities and cancer-associated heart disease (related to direct myocardial damage or secondary to the use of chemotherapy). The chronic direct deterioration on myocardial fiber is the most frequent pathophysiological mechanism observed in these groups16.

Hypertension is the most frequent clinical history in patients with HF. Our presentation ratio is visibly different compared to what it is reported in studies in Mexican population such as ENSANUT 201625 (25.5%) and lower than RENASICA28 and RENASICA II29 (46% and 55%, respectively); whereas in international multicenter studies, it is similar to that reported in studies such as MAGGIC23, SOLVD30, and CONSENSUS31 (41%, 41.5-42.8%, and 19.2%, respectively). On the other hand, type II diabetes was estimated by the RENASICA study in 50% and by RENASICA II in 42%28,29, whereas multiple international studies (CHARM32, MERIT33, FRAMINGHAM34, PARADIGM35, SOLVD30, MAGGIC23, CONSENSUS31, and RALES36) have a similar relationship with this report. Importantly, the history of myocardial infarction observed in this study is lower compared to national and international studies23,25,28-36. Only 10% had a history of interventional coronary procedures and 4% had a history of bypass surgery. Nearly one-fourth of patients had a history of smoking; only 1% of them were declared as persistent at the time of the study. Of note, only a discreet proportion of patients (1%) showed anemia in laboratory tests and another (1.4%) had a history of stroke.

The population in this report was mainly made up by carriers of HF classified as chronic; the distribution of the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class observed is mostly Classes I and II, whereas advanced Classes III and IV NYHA is made up of a smaller size group. The data show that HF is largely a disorder seen on an outpatient basis, whereas a smaller portion has acute decompensation or requires advanced medical care. It is recognized that due to drug therapy and compliance to guidelines, there is an improvement in survival, number of hospital readmissions, and QoL13. In addition to one of the main therapeutic objectives in our center, we intend to keep patients in optimal functional classes with appropriate QoL. It is necessary to detect those cases of high risk due to acute or progressive deterioration of the disease (Classes III and IV) to offer advanced therapies (electrical, hemodynamic, or surgical).

Thus, we believe that the HF spectrum in practice, has a very broad clinical horizon, that is made up by asymptomatic cases or discrete symptoms, in which patients do not go or rarely go to a specialized assessment (we suspect that they represent a large part of our population), going from that large proportion of patients who show signs and symptoms, who receive hospital, medical care, to that spectrum with advanced evolution and severe state (acute or chronic) associated comorbidity.

The most commonly reported symptom by patients is dyspnea, in its modalities such as at rest, on great exertion, and to a lesser extent paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea and orthopnea. In several multicenter trials28,29,33,34 such as patient registries with HF, the relevance of this symptom is also stated. Importantly, the clinical observation of progressive deterioration should alert the clinician to take therapeutic measures and encourage lifestyle changes that help correcting bad clinical course.

Water retention (due to edema of the pelvic limbs, ascites, or lung rales) is the clinical expression of volume overload, increased ventricular filling pressure, and diastolic failure. It is reported that 95% of patients enter the emergency room for fluid retention and dyspnea17, overcrowding these services.

We assessed, in our group of patients, through the EMPHASIS19 scale a low-to-moderate risk for cardiovascular mortality and hospitalization due to HF and moderate risk for HF mortality with the MAGGIC20 scale. This study describes the initial group of patients with HF in Mexico, which we will follow-up as planned in our clinical research program.

Conclusions

HF boasts an ample spectrum of clinical presentations ranging from patients who are completely asymptomatic to complete physical disability in late stages, pulmonary edema, and cardiogenic shock. Our findings determine that less 7% of patients are classified as NYHA IV.

Mexico is in dire need for strategic planning in accordance with its local, regional, and national reality. All this with the end goal of implementing public health policies for detecting new cases, bringing opportune diagnosis, efficient treatment, relevant cardiac rehabilitation but above all, a real and effective prevention initiative.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)