Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Comunicación y sociedad

Print version ISSN 0188-252X

Comun. soc n.29 Guadalajara May./Aug. 2017

Articles

Women stereotyping in political advertising. Analysis of gender stereotypes in electoral spots during election campaign of Nuevo Leon 2015

1Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, México.

Portrayals of social groups in the media contents has been largely characterized by the presence of stereotypes. To determine the women featured image in political advertising, a content analysis of spots from the election campaign for governor of Nuevo Leon 2015 was developed. The study shows how spots promote and disseminate gender stereotypes.

Keywords: gender; stereotypes; political advertising; election campaign

Los retratos de los grupos sociales en los mensajes mediáticos están caracterizados en gran medida por la presencia de estereotipos. Con el objetivo de determinar la imagen de la mujer en la publicidad política, se realizó un análisis de contenido de los spots de la campaña electoral a gobernador de Nuevo León de 2015. El estudio muestra cómo se fomentan y difunden estereotipos de género en los spots.

Palabras clave: Género; estereotipos; publicidad política; campaña electoral

Introduction

The entrance door for women into the public space, as citizens with equal rights and obligations in Latin America has been represented by the struggle in favor of women through the campaign to obtain the women’s vote (Peschard, 2003). That was the moment since which social theories, international movements, research, debates and discussions among feminists strengthened by establishing clearly that women’s participation was and still is a corner stone in each and every great historic event that have made a mark in the direction taken by the nations (Hinojosa, 2006).

In Mexico, since the recognition of women’s vote in 1953, a system of quotas has been legislated within the civic-democratic context to have access to publicly-elected offices with the objective of increasing the presence of women in the political representation spaces. Adopted since 1996 and amended on several occasions, said quota system has consolidated in the Reforma Político Electoral 2014 (Political Electoral Reform). In view of this reform, the country faces the new political stage in which, in addition to gaining access to representation offices, which is something that has already apparently been achieved, it is imperative to do away with the contextual framework of stereotypes and prejudice with which the role of women is usually represented (Beaudoux, 2014a; Peschard, 2003).

This need is marked by the fact that it has often been observed that the presence of gender stereotypes in the political field has usually brought about two types of negative opinions about the women who seek to gain access to power: they are either deemed unprepared for the office or otherwise, when they are competent women, they are often disapproved of or rejected on a personal and social levels, since with their behavior they challenge the prescriptive beliefs of what a desirable conduct in the feminine gender is (Beaudoux, 2014a). No doubt a predominant way in the formation of these stereotyped images is through the role the media play in their representation of reality, since the most common group stereotypes, and therefore gender stereotypes, are spread, created and/or recreated by them (Brown Givens & Monahan, 2005; Muñiz, Marañón & Saldierna, 2014).

That is why it is necessary to analyze what traits determine the image of woman as transmitted by political propaganda, and determine whether it contributes to the transmission of gender stereotypes (Marugán & Durá, 2013). This way it will be possible to know how women are reflected within politics, whether it is as a group with portraits and in positions similar to that of other social groups, or rather as a minority group and even a weak one within politics. This fact presupposed a motivation to conduct this research, because though it is not possible to prevent programs and publicity from spreading stereotyped images on a daily basis, at least it is possible to raise awareness about the propaganda distributed in electoral campaigns, specifically on the political spots. In this regard, it should not be forgotten that images of social groups are presented through the media contents which should seek to show a correct, non-stereotyped representation, one that would be free of elements that can lead to prejudice (Beaudoux, 2014b; Lita & Monferrer, 2007).

In connection with the antecedents presented, this research has the objective of determining whether the image of women presented on the spots broadcast on television during the electoral campaigns is created -intentionally or not- through the use of gender stereotypes, as well as determining what roles they are presented in. Regarding this objective, the present article analyzed the female characters present on the spots produced by the four main candidates2 during the electoral campaign for the governorship of the state of Nuevo León in 2015, in Mexico (Comisión Estatal Electoral [CEE], 2015).

Theoretical framework

Basic concepts within the theory of gender

Within the cultural parameters that make up the role that society has assigned to women, there are a number of concepts that are essential to understand the position women occupy in the political context. Starting from the general, the concept of sex is a biological question that determines whether a human being is classified as man or woman on the basis of the reproductive organ they possess. Whereas gender is supported by a sociocultural construct, which acquires a category that groups all the psychological, social and cultural aspects of femininity within the historical process of the social construction (Santi, 2000).

In addition, the concept of gender role can be defined as “the set of rules established socially for each sex” (Santi, 2000, p. 569). In society, and according to the patriarchal model that resorts to nature to explain the differences between genders, it is usually pointed out that being a woman implies or means being a mother, wife and housewife. Moreover, these are roles that are played in the family context and they constitute referential frameworks that influence women since their childhood (Hinojosa, 2006).

It should be pointed out that it is within these cultural parameters of gender perspective and representation that the female identity is constructed, since it is difficult for it to create itself. This construction of identities entails considering multiple factors: place of birth, race, the language spoken and the space inhabited. The ways of life shape the identities that, seen from the gender perspective, add one more element to the social context from which individual and collective identities are established (Hinojosa, 2006).

In his book about the political participation of women in an urban movement in Nuevo León, Rangel (2006) speaks about the distinction mentioned by Rousseau about women’s position between the political and the private space. In this regard, this author pointed out that the woman was to be placed outside the “public domain”. Starting from this precept, the author asks “how can we speak of political equality when the individual personality of women was denied?” (Hinojosa, 2006, p. 39). This way, and facing the same question, the conclusion was reached that the real problem of the scant participation of women in the political sphere was mainly due to their invisibility. In this regard, Rangel Juárez (2015) points out:

The lack of visibility is above all supported by stereotypes that promote the collective imaginarium of women in their role in society; reducing and subordinating their participation to the few spaces the male hegemony concedes to them as a subordinate gender (p. 9).

In this sense, the phenomenon of stereotypes can be understood within the broad context of categorization (Muñiz et al., 2014). Stereotypes have a basic function for the individual’s socialization: they facilitate social identity and the sense of belonging, since accepting to identify with the dominant stereotypes in a given group is a way of remaining integrated in it (Gabaldón, 1999). Stereotypes are usually defined as “beliefs that are more or less structured on a subject’s mind about a social group” (Páez, 2004, p. 760). That is, they fulfill an important cognitive function for the individual, inasmuch as they are "cognitive structures that contain the subject’s knowledge and beliefs about different social groups" (Martínez, 1996, p. 21).

It must be added that these stereotypes are formed unconsciously by the individuals, due to the fact that social conduct patterns are implanted in the subconscious since childhood and they are reaffirmed over time (Beaudoux, 2014b). However, they can also be eliminated or modified depending on the capacity for conscience, adaptation and dominion an individual has about them. This is due to the fact that, although they are generalizations about the defining characteristics or traits that are perceived to characterize the members of exo-groups, they can change as a result of a process of relation with representatives of these other groups. Within social stereotypes in general, Gabaldón (1999) points out that gender stereotypes are a subtype, and they can be defined as “beliefs held by consensus about the different characteristics of men and women in our society” (p. 84).

Inequalities of qualities and social status can represent an obstacle in the opportunities for women to gain access to a political career. From the different cultural criteria that have been revealed to shape women’s inequality, the expression “glass ceiling” was coined with the objective of describing that invisible barrier that prevents women’s access to leadership positions, both within the social scale, as executives and as elected officials (Beaudoux, 2014b; Marugán & Durá, 2013).

However, although in democratic societies such as the Mexican one, in theory the rights and obligations stipulate a principle of equality between men and women, in practice the sense and respect of said theoretical principles is lost. A reality that has posed the need to replace the expression “glass ceiling” by that of “glass labyrinth”, a metaphor that exposes the probability that women may get lost on the intricate roads of a metaphorical place that, even though it has an entrance, it generally presents a very complicated exit (Barberá, Ramos& Candela, 2011 cited in Marugán & Durá, 2013).

The role of the media in the diffusion of stereotypes

Human beings are sociable by nature, that is why it causes them to fall in a process of dependence, not only in their environs but also of the people that surround them (Gabaldón, 1999). However, over time the contexts of dependence have evolved and they are ever more demanding. Socialization, therefore, becomes a key factor in this process, which is in addition different regarding the people’s sex. That is, gender stereotyping will occur, a sort of labels that accompany people due to the mere fact that they belong to one or the other sex (Lita & Monferrer, 2007). Along with the conflict that entails the socialization process that accompanies the individuals, today there is a new challenge to face: the role of the media in the transmission of stereotypes and the generation of prejudices (Dixon, 2000; Muñiz, Serrano, Aguilera & Rodríguez, 2010; Seiter, 1986). According to Orozco Gómez (1997), the media can be defined as:

Languages, metaphors, technological devices, platforms where power is generated, won or lost; they are mediations and mediators, logics, business companies; they are control and social-molding instruments, and at the same time, they are cultural revitalizers and the source of everyday referents; they are educators, and presenters of reality and they are generators of knowledge, authority and political legitimization (p. 26).

They have been omnipresent in political campaigns since the end of the 20th century, gaining strength in the game of political marketing in the last few years. Especially with the use of political advertising, through the news coverage offered about election campaigns and, of course, through the budgets assigned to the TV networks. These facts have necessarily revealed the important role played by the media in the election processes, as well as the effects generated in the citizens by the consumption of their contents (Huerta & García, 2008).

The cultivation theory put forward by Gerbner and his team of collaborators at the end of the 1960’s stands out among the studies on the representations of social groups in the media. The extent of the influence of TV has been analyzed from this theory as well as the effects the media have on the individuals, and in the generation of attitudes through its contents (Beaudoux, 2014b; Behm-Morawitz & Ortiz, 2013; Brown Givens & Monahan, 2005; Muñiz et al., 2014). And as Shanahan and Morgan (1999) pointed out when they review the theory, “much of what we know, or think we know, we have never personally experienced; we ‘know’ about many things based on the stories we hear and the stories we tell” (p. 13). That is, reality or the perception we have of reality is the result of everything we hear or watch through someone else, without being the protagonists, but rather the spectators in a context of the society that we assume as real.

No doubt this would not represent a relevant fact if it had not been discovered that the more an individual is exposed to the media, in particular to television, the more their view of social and political reality looks like the referent represented on the media rather than like the objective referent that statistics and social reality can show (Gerbner, 1998). In sum, those individuals that have been subjected to high media exposure, to a larger extent tend to hold prejudices and stereotyped gender conceptions that coincide with the media narratives (Beaudoux, 2014a; Muñiz et al., 2010).

Therefore, the media can play a crucial role in the process of “stereotyping” (Brown Givens & Monahan, 2005; Muñiz et al., 2014), which involves the activation of certain stereotypes and their application to make subsequent value judgments. And the point is that through their contents they contribute to the representation of social groups and the activation among the audience of a system of personal beliefs about the social groups, from the use of certain stereotypes that are believed to define these groups. A process that is amplified when the stereotyped images of the groups are repeated continually over time, as it can happen through the constant use of certain stereotypes to portray the groups in the media contents (Brown Givens & Monahan, 2005).

This process is not likely to be alien to women’s image in politics as portrayed by the media in their contents. And the point is that, due to the fact that many leadership or strength qualities are generally built thinking of male qualities, it is common for representations of women in the media contents to derive into stereotypes that show women as politically inept, lacking in knowledge, weak in character and devoid of autonomy or just as mothers (Marugán & Durá, 2013; Pérez, 2009). A representation that begins this stereotyping process, and that can derive into the shaping of thoughts, attitudes and value judgments with respect to women connected with politics.

Gender minorities in the political advertising

As it has been pointed out, to a large extent the opinions and values that prevail among citizens with respect to public issues depend on the messages they receive through the media (Dixon, 2000; Seiter, 1986). That is why they have been pointed at as responsible for social mediations (Orozco Gómez, 1997; Sánchez-Tabernero, 2008), as well as for the creation or mass diffusion of stereotypes and prejudices that concern minorities or minority groups (Barbalho, 2005; Behm-Morawitz & Ortiz, 2013; Brown Givens & Monahan, 2005).

Though the concept of minority or minority group is commonly used, it should be convenient to make some considerations about its scope and use. In this regard, Guillaurnin (1992 cited in Osborne, 1996) explains that minority groups are not necessarily those that, due to the small number of their members, are also the smallest in number in society. They should rather be considered as such when they are in a state of “lesser power” in a society, whether this power is economic, legal or political (p. 80). This premise can also be adopted in the case of women, who are usually assumed as a minority group. As Osborne (1996) indicates “this definition of minority, resulting from the inferiority of status, and not from their statistic relevance, is what allows the sociologic approximation between the so-called ethnic minorities and women” (p. 80).

Moreover, regarding deliberative spaces, even though an ever-wider space is emerging for more and more women to join, it is not possible to speak of a large number or claim that this process is occurring rapidly. However, this presence that women are adopting in the social system is an indicator that helps us to observe, measure and interpret the political progress made by women (Marugán & Durá, 2013). That is why it is essential to analyze and reflect on the degree of influence the media have, and within the political contents the influence exerted by advertising spots, since as Díaz-Soloaga and Muñiz indicate (2007):

Though it is true that the aim of publicity is not to educate (except for those -like the institutional one- whose explicit aim is precisely that) or to transmit positive values, it is however also true that regardless of the producers’ intention and thanks to the use of symbols recognizable by the audience, publicity transmits -whether they want to or not- life styles, proposals about how one should be, act, …, to be successful on the social scale (p. 77).

Taking this into account, it is important to analyze how the role played by the woman is represented and transmitted in the political campaigns, in particular through the political spots produced by the candidates. This is due to the fact that they are audiovisual messages containing fragments of visual, verbal and oral communication, through which a candidate or political party buys time on the media seeking to influence the vote decision among the people (Lita & Monferrer, 2007), which makes the spots one of the most important messages for conveying political information to the citizenry in election contexts (Marañón, 2015; Muñiz et al., 2010; Ramos, 2014).

Considering the antecedents presented, this research aimed to contrast the following research hypothesis and to answer the following research questions in the context of the electoral campaign for the governorship of the Nuevo León State in 2015:

H1: The spots produced by the different candidates to the elections included stereotyped portraits of women through the inclusion of female characters that showed gender stereotypes.

RQ1: What are the prevailing stereotypes and representations with which the image of women was presented on the political spots during the elections?

RQ2: Were there any differences among the candidates when it came to representing women within their election spots?

Methodology

Research design

In order to conduct a research project, it is necessary to carry out a design that allows adequate attainment of the aims set, as well as a “clear, concrete and precise analysis of the problem and a rigorous research methodology suitable for that kind of work” (Noguero, 2002, p. 167). That is why when conducting this research we analyzed the political spots aired during the election for governor in 2015 in the Mexican state of Nuevo León by means of the content analysis technique.

This technique is defined as the set of interpretative procedures for communicative products (messages, texts or discourses) that originate from previously recorded unique communication processes and supported by techniques that are sometimes quantitative (statistics that support counting the units) and sometimes qualitative (logics that are based on the combination of categories), they intend to encode aspects that are considered relevant about the units of analysis (Raigada, 2002). That is, characteristics that must be evaluated and placed in relation so that the latent information present in the units of analysis emerges.

To this end, we selected a sample of spots broadcast by the four main candidates to the governorship, which were determined depending on the vote intention in the surveys presented through the different newspapers with a presence in the state such as: El Norte, El Horizonte, Hora Cero and El Universal. In this sense, the analysis covered the spots by Ivonne Álvarez García, nominated Alianza por tu Seguridad that was made up by Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI), Nueva Alianza (Panal), Verde Ecologista de México (PVEM) and Partido Demócrata, by Felipe de Jesús Cantú, the banner holder of Partido Acción Nacional (PAN), by Fernando Elizondo Barragán, registered by Movimiento Ciudadano, and by independent candidate Jaime Rodríguez “El Bronco” (“Nueve estados en juego”, 2015).

According to the Instituto Nacional Electoral (National Electoral Institute, INE) (2015), the election campaign covered from March 6th, 2015 to June 7th 2015, election day. During this period, a total of 95 spots were broadcast on television. Of these, 53 correspond to the four main candidates and parties that were analyzed in this research. However, due to the fact that the object of study focused on analyzing the gender stereotypes transmitted in these spots that could affect the political perception people have of women, we only took into consideration those spots where female figures appeared or those whose message addressed specifically this population sector.

Finally, a sample of 28 spots was selected of which ten corresponded to the PAN candidate, 11 to the female candidate for the Alianza por tu Seguridad coalition, five to the candidate for Movimiento Citizen and just two to the independent candidate. Within the spots, the “character” appearing on the ad was used as the unit of analysis, as a result revealing a total of 130 units of analysis: 51 corresponding to the spots analyzed for the PAN candidate, 58 units corresponding to the Alianza por tu Security female candidate, 18 to the partido Movimiento Ciudadano candidate and 3 units to the independent candidate.

Instrument used and reliability analysis

A code book was created for this research with a total of 29 variables, concerning both the general relative data of the spot content and the characters present in them. Regarding the data concerning the female characters, the analysis focused on a set of 14 variables associated with image, age, clothes, role, disability, tone of voice, university education, the character’s initiative or their esthetic appearance (Díaz-Soloaga & Muñiz, 2007). For example, “the character’s age group” was measured, where the encoder had to choose from 0 = cannot be encoded, 1 = younger than 15 years, 2 = Young, from 15 to 30 years approximately, 3 = Adult, 30 to 65 years and 4 = Older, over 65 years.

The selection of said variables to make up the code book was made on the basis of the assumption that many of a politician’s leadership or strength qualities are built in general thinking of male qualities (Beaudoux, 2014a, 2014b). That is why it is important to determine the presence of other aspects that can determine whether women are represented, on the contrary, as politically inexpert, lacking in knowledge, weak of character and lacking in autonomy or simply as mothers (Marugán & Durá, 2013).

When the codification of the units corpus selected was finished, a reliability analysis was performed to allow confirming the inter-rater agreement obtained, that is, the level in which it can be assumed that there was no bias in the codification of the variables defined in the book for each of the units of analysis. To this end, 70 units of analysis were randomly selected from the total number of samples to perform a second codification. Two new encoders participated, they were chosen with the premise of having previously collaborated in other content analyses, and they were over 18 years of age and were senior undergraduate or graduate students. They were previously trained in regards to the book of codes and the codification fiche they would have to use. After this, the information of the second codification performed by the complementary analysts was collected and captured in the data base with the statistic software SPSS v.19.

To check the inter-rater agreement of the content analysis, the kappa coefficient reliability test was used; the test had been originally proposed by Cohen (1960) for the case of two raters or two methods. The kappa coefficient can take values ranging between -1 and +1. The closer the value is to +1, the greater the degree of inter-observer agreement. Contrariwise, the close the value is to -1, the greater the degree of inter-observer disagreement (Krippendorff, 2004). This way κ value = .80, was obtained which indicates the study’s high reliability.

Analysis of the results

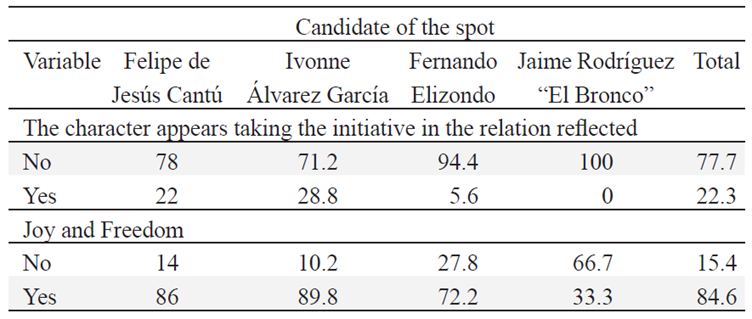

With the end of determining the stereotypes used in the spots presented by the four candidates analyzed, this part of the diagnosis of descriptive variables focuses on studying the units of analysis corresponding to female characters as such. According to Table 1, “the type of character” in which most of the characters analyzed were classified was the category of “Supporting Character” which corresponded to 58.5% of the units analyzed. As to the category occupying the second place, corresponding to 27.7%, belongs to people presented as “the Main Character”, a variable in which independent candidate Jaime Rodríguez stands out, presenting 100% of his characters in this category X2(6, N = 130) = 11.705,p = .069. Respecting the remaining 13.8%, they were presented as “Background”, so even though they were present on the spots, their participation was not essential, but it met the requirements marked and necessary to be part of the analysis.

Table 1 Differences among the candidates in terms of type of character, age group and use of an aggressive tone of voice by the character (results presented in percentage column)

Source: the author.

Regarding the “Age group of the female character” X2(N = 130, 9) = 100.535, p < .001 they were mostly “Adult” characters, referring to people in an age range between 30 and 65 years with 60% of the units, and the only female candidate stood out by presenting 66.41% of her characters within this category; while 24.6% of the characters correspond to the age group “Young” ranging in age from 15 to 30 years, here the independent candidate stood out by presenting 67.7% of his characters in this group, followed by candidate Fernando Elizondo who presented 50% of his characters in this category. 14.6% of candidate Felipe de Jesús’s characters were placed in the age group “Older”, by presenting el 26%. Finally, only 0.8% corresponded to the under 15 group, and Álvarez was the only person who presented characters in this age range (see Table 1).

Finally, regarding the “Use of an aggressive tone of voice” it was possible to observe that the aggressive tone was not used in 26.9%, while only 1.5% did use it X2(N = 130, 6) = 91.623, p < .001. It should be highlighted that all the characters of independent candidate Jaime Rodríguez presented this feature (see Table 1).

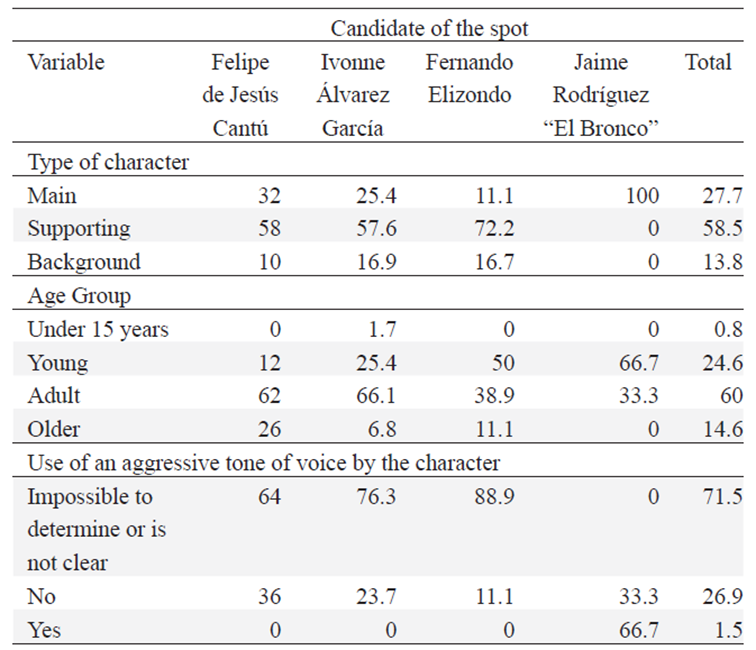

With respect to the “main role of the female character” with which they were associated, most of the units of analysis were presented as “Heads of the household”, X2(N = 130, 18) = 97.362, p < .001. This role was followed by that of “blue-collar workers” with 13.8%, in a similar situation to that of the category “students” with 12.3%. 3.8% of the units were classed within the role of “business woman”, while the role or “farmers” was represented by 2.3% of the characters. Moreover, and with just 0.8%, characters were presented in their roles of “small business owners” (see Table 2).

Table 2 Differences among the candidates in terms of the main role of the female character (results in percentages)

Source: the author.

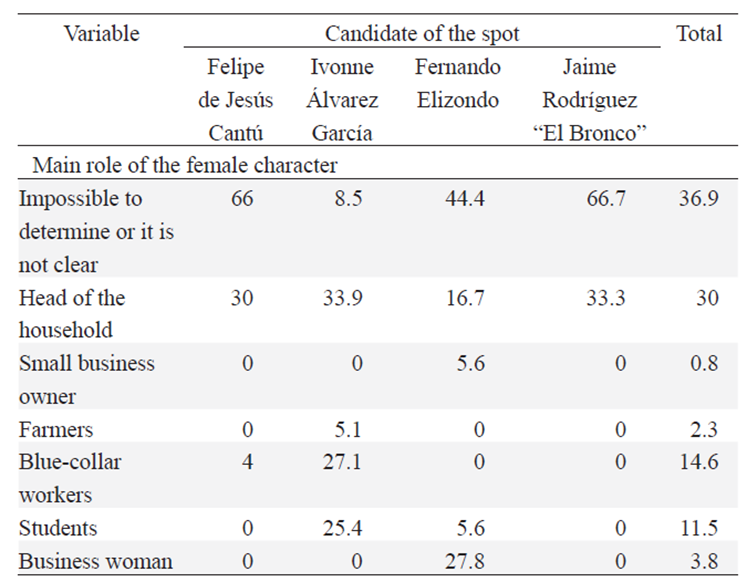

Regarding the “image of the character”, it was analyzed whether it was presented as someone who had studied at the university, X2(N = 130, 6) = 11.343, p= .078. In this respect, it is noteworthy that only 32.3% were associated with someone who had had a university education. In contrast, 15.4% were not associated with an image of someone who had studied, while in 52.3% of the cases, it was impossible to identify this feature. It should be pointed out that, in the case of independent candidate Rodríguez, it was not possible to determine the image of any of his characters regarding the association with someone who had had a university education. As to “professional success”, 23.8% of the characters presented this appearance in the spots X2(N = 130, 3) = 4.230, p = .238. However, the majority did not denote the esthetic appearance with 76.2% (see Table 3).

Table 3 Differences among candidates in terms of the character image presented or associated as someone with a university education and professional success (results in percentages)

Source: The author.

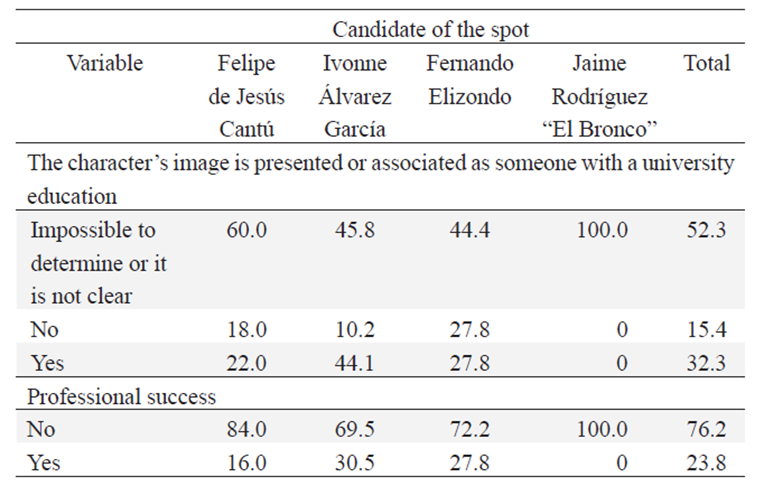

Finally, regarding whether the character appeared as a person with their own initiative during the development of the narrative in the spot, for the most part it was observed that the characters did not take the initiative, X2(N = 130, 3) = 5.220, p = .156, this fact represented 77.7%. In turn, only 22.3% of the characters were presented as active and resolute in the actions that were reflected on the spot, and as to the variable referring to the female character’s esthetic appearance of “Joy and Freedom”, 84.6% of the characters showed that feeling of joy and freedom, leaving only 15.4% of characters that did not convey this appearance X2(N = 130, 3) = 9.491, p = .023 (See Table 4).

Discussion and conclusions

It is undeniable that the media exert a great influence on politics, as it was discussed above, specifically by means of advertising tools and strategies such as spots, since they can mould the people’s beliefs and attitudes as social reality (Marañón, 2015). However, in Mexico there is no research targeting the study of political spots as the diffusers of gender stereotypes. That is why this research paper was carried out on the basis of the content and result analysis by means of a quantitative study.

The analysis revealed that, of the 14 variables developed with respect to the data related to the female characters, 7 proved to be positive in the promotion and diffusion of gender stereotypes. This agrees with the notion that advertising encourages certain stereotypes of “how” or “what” a woman must do to be commonly accepted by society (Díaz-Soloaga & Muñiz, 2007). That is why it is worrying that at present, both in advertising and in politics, the female images diffused on the media, especially on political advertising, are usually negative and loaded with stereotypes (Lita & Monferrer, 2007).

As to the research hypothesis put forth, about the fact that the spots presented women with gender stereotyping, on the basis of the findings obtained in the present research it can be concluded that, indeed, the candidates presented advertising that spread -voluntarily or not- this type of stereotypes during the 2015 election campaign analyzed. This represents, no doubt, an alarming fact considering that it is through the media that modifications are generated in political and social attitudes.

As to the first research question, referring to what the prevailing stereotypes and representations were, placing the woman on the political spots during the elections, it was found that the main role in which the characters were presented was “head of the household”. These characters were mostly represented as playing “supporting” roles, with an age range of “30 to 65 years”, at the same time; they did not take the initiative in the actions that were reflected on the spot, but in most cases the female characters reflected an esthetic appearance of “joy and freedom”.

In Rangel’s (2006) words, it should be pointed out that according to the patriarchal model of our societies, being a woman means “being a mother, wife and housewife” (p. 90), these roles are played within the family and they seem to be reflected by the spots produced by the different candidates analyzed. Regarding the stereotypes conveyed by the spots, it is possible to observe that male characters appear more often in leading roles, while the opposite is true of the women. When analyzing the age variable, it was revealed that women are portrayed as unproductive and passive from their middle age onwards. In sum, the image that women are people with more limited interests and capacities is conveyed and the notion that they are happier when they stay home is held, just as it had been indicated by other authors, in agreement with what has been revealed by previous studies (Beaudoux, 2014a, 2014b).

In addition and in keeping with the results found, the second research question was answered. Regarding the existence of differences among the candidates when it came to representing women on their spots it can be concluded that, of the 18 variables compared among the four candidates, 10 derived into differences. In this sense it is concluded that, according to the variables contrasted, both Felipe de Jesús Cantú and Ivonne Álvarez presented a classical image of the woman associated with the stereotype “housewife-woman”. An image that reduces the woman’s function to taking care of the family and the household where the values of “love”, “warmth”, “sensitivity” and “happiness” are reflected (Pérez, 2009; Díaz-Soloaga & Muñiz, 2007). The differences between these two contenders lay, however, in the “passive and/or submissive attitude” in which their female characters were presented, because while the PAN candidate did not present any character with this kind of attitudes, the Alianza por Tu Security female candidate, presented 5.1% of her characters within this category.

With respect to the Movimiento Ciudadano candidate, he presented a female image that is far from that of his rivals, since most of his characters played the role of “business woman” working in a profession, women whose ages ranged from 15 to 30 years, who conveyed an appearance of joy, sex appeal and leisure. In this sense, a “functional-modern” stereotype was detected associated with an image of “modernity”, “freedom” and “comfort” (Díaz-Soloaga & Muñiz, 2007, p. 85)

In the case of the independent candidate, Jaime Rodríguez “El Bronco”, who eventually won the elections, his spots revealed a stereotyped image associated with the “young woman”. However, it was far from being the positive image of a youthful female character, even when his characters were in the same age range as Fernando Elizondo’s. Quite the contrary, the image of the woman on his spots is regarded as lacking in knowledge and as a transgressor of socially-accepted rules of conduct (Lita & Monferrer, 2007; Marugán & Durá, 2013). In addition, the candidate presented mostly young characters between 15 and 30 years of age who used informal, aggressive language.

Last but not least, it is important to point out that it is imperative to continue to strive to carry out research of this type in the future, due to two main reasons. First, as it was indicated above, because there is not enough research in Mexico addressing this line of analysis, therefore there is still a lot to be explored in this field. Secondly, there are very few public policies that take these studies as their foundation, which would allow reducing the social perception of gender prejudice and stereotypes that abound in society (Lita & Monferrer, 2007)

REFERENCES

Barbalho, R. P. (2005). Comunicación y cultura de las minorías. Bogotá: Editorial San Pablo. [ Links ]

Beaudoux, V. G. (2014a). Influencia de la televisión en la creación de estereotipos de género y en la percepción social del liderazgo femenino. La importancia de la táctica de reencuadre para el cambio social. Ciencia Política, 9(18), 47-66. [ Links ]

Beaudoux, V. G. (2014b). Estereotipos de género y liderazgo femenino. Ponencia presentada en el VI Congreso Internacional de Investigación y Práctica Profesional en Psicología, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Recuperado de http://www.aacademica.org/000-035/502 [ Links ]

Behm-Morawitz, E. & Ortiz, M. (2013). Race, ethnicity, and the media. En K. E. Dill (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Media Psychology (pp. 252-266). Nueva York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Brown Givens, S. M. & Monahan, J. L. (2005). Priming mammies, jezebels, and other controlling images: An examination of the influence of mediated stereotypes on perceptions of an African American woman. Media Psychology, 7 (1), 87-106. doi:10.1207/S1532785XMEP0701_5 [ Links ]

Carrizales, D.( 21 de marzo de 2015). NL: Inician proceso con récord de partidos y candidatos. El Universal. Recuperado de http://archivo.eluniversal.com.mx/estados/2015/nl-inician-proceso-con-record-de-partidos-y-candidatos-1086385.html [ Links ]

Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20 (1), 37-46. doi: 10.1177/001316446002000104 [ Links ]

Comisión Estatal Electoral-CEE Nuevo León. (2015). Calendario de actividades para el proceso electoral 2014-2015. Recuperado de http://www.cee-nl.org.mx/pe/2014-2015/documentos/2014101601_Calendario%20Electoral%202014-2015.pdf [ Links ]

Díaz-Soloaga, P. & Muñiz, C. (2007). Valores y estereotipos femeninos creados en la publicidad gráfica de las marcas de moda de lujo en España. Zer- Revista de Estudios de Comunicación, 12 (23), 75-94. [ Links ]

Dixon, T. L. (2000). A social cognitive approach to studying racial stereotyping in the mass media. African American Research Perspectives, 6 (1), 60-68. [ Links ]

Gabaldón, B. G. (1999). Los estereotipos como factor de socialización en el género. Comunicar, 12, 79-88. [ Links ]

Gerbner, G. (1998). Cultivation Analysis: An overview. Mass Communication and Society, 1 (3-4), 175-194. doi: 10.1080/15205436.1998.9677855 [ Links ]

Huerta, J. E. & García, E. (2008). La formación de los ciudadanos: el papel de la televisión y la comunicación humana en la socialización política. Comunicación y Sociedad, 10, 163-189. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional Electoral-INE. (2015). Votos Por Partido. Monterrey: INE. Recuperado de http://prep2015.ine.mx/Entidad/VotosPorPartido/detalle.html#!/19 [ Links ]

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

Lita, R. L. & Monferrer, E. B. (2007). Publicidad, medios de comunicación y segregación ocupacional de la mujer: perpetuación y superación de los estereotipos de género y sus consecuencias en el mercado de mano de obra. Revista del Ministerio de Trabajo e Inmigración, 67, 213-226. [ Links ]

Marañón, F. D. (2015). El spot como herramienta de persuasión política. Análisis del impacto de la publicidad política en la desafección política a través de la ruta central y periférica. Tesis doctoral. Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Monterrey. Recuperado de http://lacop.uanl.mx/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Tesis_Felipe.pdf [ Links ]

Martínez, M. C. (1996). Análisis psicosocial del prejuicio. Madrid: Síntesis. [ Links ]

Marugán, P. R. & Durá, J. F. (2013). El liderazgo político femenino: la dificultad de una explicación. Raudem: Revista de Estudios de las Mujeres, 1, 86-109. [ Links ]

Muñiz, C., Marañón, F. J. & Saldierna, A. R. (2014). ¿Retratando la realidad? Análisis de los estereotipos de los indígenas presentes en los programas de ficción de la televisión mexicana. Palabra Clave, 17(2), 263-293. doi: 10.5294/pacla.2014.17.2.1 [ Links ]

Muñiz, C., Serrano, F. J., Aguilera, R. E. & Rodríguez, A. (2010). Estereotipos mediáticos o sociales. Influencia del consumo de televisión en el prejuicio detectado hacia los indígenas mexicanos. Global Media Journal México, 7 (14), 93-113. [ Links ]

Noguero, F. L. (2002). El análisis de contenido como método de investigación. XXI. Revista de Educación, 4, 167-179. [ Links ]

Orozco Gómez, G. (1997). Medios, audiencias y mediaciones. Comunicar, 8, 25-30. [ Links ]

Osborne, R. (1996). ¿Son las mujeres una minoría? Isegoria: Revista de Filosofía Moral y Politica,14, 79-93. [ Links ]

Páez, D. (2004). Relaciones intergrupales. En D. Páez, I. Fernández, S. Ubillos & E. Zubieta (Coords.), Psicología social, cultura y educación (pp. 752-768). Madrid: Pearson Educación [ Links ]

Pérez, N. G. (2009). La mujer en la publicidad.Tesis de maestria no publicada. Universidad de Salamanca, España. Recuperado de http://gredos.usal.es/jspui/bitstream/10366/80263/1/TFM_EstudiosInterdisciplinaresGenero_GarciaPerez_N.pdf [ Links ]

Peschard, J. (2003). Medio siglo de participación política de la mujer en México. Revista Mexicana de Estudios Electorales, 2, 13-33. [ Links ]

Raigada, J. L. (2002). Epistemología, metodología y técnicas del análisis de contenido. Estudios de Sociolingüística, 3 (1), 1-42. [ Links ]

Ramos, M. M. (2014). Principales estudios realizados sobre la representación de las minorías en la ficción televisiva. Chasqui, 126, 98-108. [ Links ]

Rangel Hinojosa, A. (2006). Participación política de las mujeres en un movimiento urbano de Nuevo León. Ciudad de México: Plaza y Valdés. [ Links ]

Rangel Juárez, G. B. (2015). De las cuotas a la paridad, ¿qué ganamos? Toluca: Instituto Electoral del Estado de México. [ Links ]

Sánchez-Tabernero, A. (2008). Los contenidos de los medios de comunicación. Calidad, rentabilidad y competencia. Barcelona: Ediciones Deusto. [ Links ]

Santi, P. H. (2000). Rol de género y funcionamiento familiar. Revista Cubana de Medicina General Integral, 16 (6), 568-573. [ Links ]

Shanahan, J. & Morgan, M. (1999). Television and its viewers. Cultivation theory and research. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Soloaga, P. D. & Muñiz, C. (2007). Valores y estereotipos femeninos creados en la publicidad gráfica de las marcas de moda de lujo en España. Zer- Revista de Estudios de Comunicación, 12 (23), 75-94 [ Links ]

2By March 21st, 2015, the newspaper El Universal (2015) had announced the four main candidates; at that moment it showed Ivonne Álvarez García, running for Alianza por tu Seguridad, made up by the parties Revolucionario Institucional (PRI), Nueva Alianza (Panal), Verde Ecologista de México (PVEM) and Demócrata, as well as Felipe de Jesús Cantú, running for Partido Acción Nacional (PAN), as the strongest candidates, followed by Independent candidate Jaime Rodríguez, “El Bronco” and the former PAN member Fernando Elizondo Barragán, registered by Movimiento Ciudadano (“Nueve estados en juego”, 2015).

Received: November 03, 2016; Accepted: December 16, 2016

text in

text in