Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Frontera norte

On-line version ISSN 2594-0260Print version ISSN 0187-7372

Frontera norte vol.35 México Jan./Dec. 2023 Epub Apr 15, 2024

https://doi.org/10.33679/rfn.v1i1.2347

Articles

Socioterritorial Conflicts in Valle de Guadalupe, Baja California, Mexico: An Approach from Trust Networks

1El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, México, andrisha.nm@gmail.com

2El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, México, nbringas@colef.mx

3Universidad de Guadalajara, México, basiliov@cucea.udg.mx

This article analyzes, from a relational perspective, interactions between participants of various trust networks and explains their role in preserving the agricultural and rural profile of Valle de Guadalupe, Baja California and its consolidation as the most important wine region in Mexico. Semi-structured interviews and newspaper content analysis were used to study various land use conflicts recorded between 2000 and 2020. Contention scenarios, action repertoires, and outcomes of previous experiences were identified. The results show a diversity of trust networks using a diverse set of mechanisms ranging from participatory innovation to patronage and discretionary appropriation. As the valley has become the country's leading wine tourism destination, these networks have made progress in conflict resolution and land protection, but still face emerging tensions due to tourism and real estate development.

Keywords: socioterritorial conflicts; trust networks; wine region; Valle de Guadalupe; Mexico

Desde una perspectiva relacional, se analizan las interacciones entre participantes de varias redes de confianza y se explica su papel en la preservación del perfil agrícola y rural del Valle de Guadalupe (Baja California) y en su consolidación como la zona vitivinícola más importante de México. Se utilizan entrevistas semiestructuradas y análisis de contenido de periódicos para estudiar varios conflictos por el uso del suelo registrados entre 2000 y 2020. Se identifican los escenarios de contienda, los repertorios de acción y los resultados de experiencias previas. Los hallazgos muestran los mecanismos utilizados por las diversas redes de confianza: la innovación participativa, el clientelismo y la apropiación discrecional. A medida que el valle se convirtió en el principal destino enoturístico del país, estas redes lograron avances en la resolución de conflictos y en la protección de la tierra, pero aún enfrentan tensiones emergentes debido al desarrollo turístico e inmobiliario.

Palabras clave: conflictos socioterritoriales; redes de confianza; región vitivinícola; Valle de Guadalupe; México

INTRODUCTION

This article examines the role of trust networks in managing socioterritorial conflicts. According to Tilly’s proposal (2007), the establishment and presence of a trust network in conflicts like those studied here can be identified by verifying the existence of interconnected groups of people with strong bonds, where members trust in the assistance and attention of others. It is also observed that participants in a network collaborate in carrying out long-term initiatives or projects, such as the perpetuation of certain land use patterns considered socially acceptable, even if their outcomes might fail due to mismanagement by the individuals within the network.

By analyzing trust networks, it is possible to study how actors or groups relate to each other, forming various links of different strengths and scopes. Within these networks, some members may participate in multiple social structures simultaneously, either to achieve common goals, access resources, or simply fulfill the need for group affiliation. These interactions can be observed in territorial matters, that is, they enable an understanding of how individual participation in networks has either benefited or affected the management of territorial resources through collaborative relationships (Ramírez, 2016).

According to Garrido (2001), the existence of social networks implies connections that influence the behavior of the actors. The trust and commitment of the members of a network become fundamental in facilitating social coordination and addressing potential conflicts among multiple stakeholders on a particular issue (Alexander et al., 2004; Hanneman & Riddle, 2005; Seligman, 1998; Tilly, 2005; Yamagishi & Yamagishi, 1994).

The functioning of networks and their role in coordinating actors can be explained from various perspectives. For instance, the rationalist approach emphasizes individuals’ behavior considering their motivations and personal interests in order to maximize their benefits (Lozares, 1996; Pierson & Skocpol, 2008; Uribe, 2009; Shaffer, 2018). Conversely, the institutionalist approach focuses on how actors operate within certain rules or conventions and how they acquire, retain, and use contingencies, knowledge, and information within institutional frameworks or arrangements (Emirbayer, 2009; Uribe, 2009; Ostrom, 2011).

On the other hand, the relational approach attempts to link individual motivations, institutional contexts, and large social processes to better understand the development of trust bonds in specific contexts. It can also be used to understand how the presence of collective actions impacts the productive dynamics of a territory from appropriation, use, and transformation, thereby alluding to social, political, economic, religious, environmental, and cultural dimensions (Tilly, 2005; Hanagan & Tilly, 2010; Krinsky & Mische, 2013). Consequently, territorial transformations emerge as a multifaceted game, yielding both winners and losers, unveiling cooperative dynamics or conflicts among social actors as they navigate adverse or advantageous circumstances to further their interests.

This article employs a relational approach to examine the conflicts arising from shifts in land usage within the Valle de Guadalupe —a region rapidly evolving towards the establishment of a tourist-wine cluster—. These conflicts stem from the recent influx of real estate ventures, as a process that has neglected the role of trust networks.

Drawing from such conflicts, this article presents evidence through two lines of research rooted in the theoretical-conceptual framework of trust networks and their operational mechanisms. For this purpose, this article is organized into sections that address the prevailing situation in the studied region, Tilly’s (2005) theoretical perspective on trust networks, the implemented methodological strategy, the presentation and discussion of findings, culminating in the presentation of conclusions.

GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE VALLE DE GUADALUPE

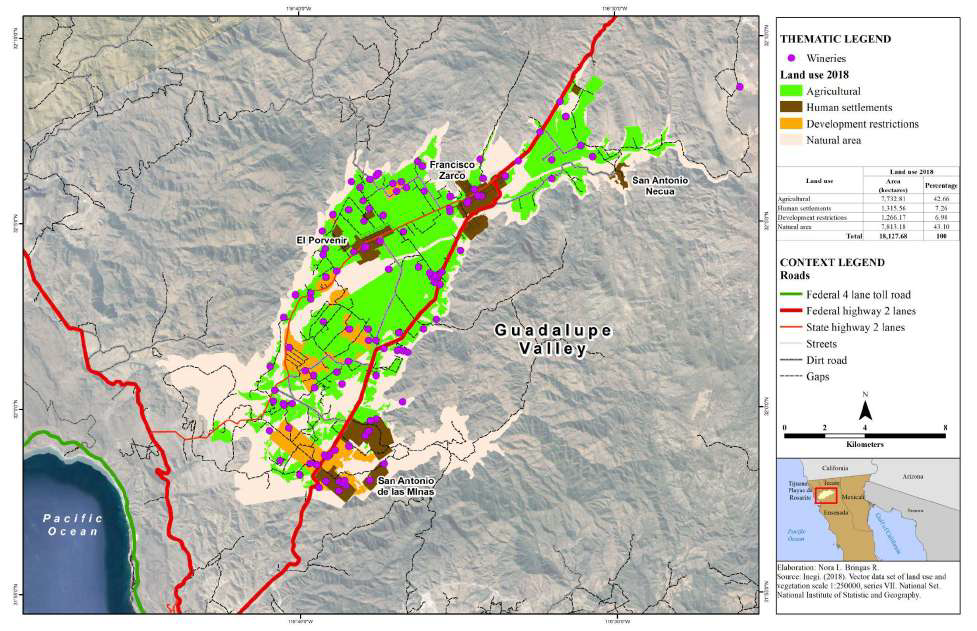

The Valle de Guadalupe is located north of the municipality of Ensenada, Baja California, 25 km away from the urban area and 85 km south of Tecate and Tijuana; it is characterized by its Mediterranean climate (Bringas-Rábago & Toudert, 2011). Until the first decade of this century, the local population’s economic sustenance was based on agriculture (Magoni, 2009), primarily suitable for the cultivation of grapevines (vitis vinifera), olive trees, citrus fruits, alfalfa, and vegetables (Secretaría de Fomento Agropecuario [SEFOA], 2011). This region spans an area of 66 353 hectares, of which 8% (5 308) corresponds to arable land (Espejel, 2022); it encompasses the margins of the Guadalupe water basin, which supplies water to this area and the population of Ensenada (see map 1).

Source: Elaborated by Nora L. Bringas-Rábago based on information from INEGI (2018).

Map 1. Location of the Valle de Guadalupe and its Main Settlements

As of 2020, the Valle de Guadalupe housed a total population of 7 089 inhabitants, primarily concentrated in its three main population centers. Among these, Francisco Zarco stands as the most populous locality, hosting 4 334 residents, followed by the El Porvenir ejido with 1 806 inhabitants, and San Antonio de las Minas, accommodating 893 inhabitants (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía [INEGI], 2020).

Traditionally, agriculture has been the economic foundation of Valle de Guadalupe. However, following the creation of the Ruta del Vino (Wine Route) in 2000, wine tourism blossomed, and waves of visitors began arriving, demanding leisure, recreation, and hospitality services in this newly discovered wine region (Quiñónez Ramírez et al., 2012; N. L. Bringas-Rábago, field diary, December 15, 2022).

Alongside the flourishing tourism industry, the interest of real estate developers grew, leading to land subdivision for residential purposes, impacting areas designated for cultivation (N. Badán, personal communication, April 25, 2020; S. Cosío, personal communication, April 28, 2020; F. Pérez Castro, personal communication, March 31, 2020). This prompted a productive change due to the immediate economic influx from tourism (Bringas-Rábago, 2014). However, this rapid expansion of the real estate sector, without proper oversight, has encroached upon and endangered the future of Valle de Guadalupe’s vital wine industry, compromising its performance.

In recent decades, the constellation of social actors with political and economic influence in Valle de Guadalupe has changed the land that originally belonged to Kumiai native groups. In the early 19th century, part of this land was acquired by Molokan Russians who reintroduced viticulture, and later, with the agrarian reform, some lands passed into the hands of ejido families and small local landowners (Quiñónez Ramírez et al., 2012). However, from the year 2000 onwards, a wave of national and foreign investors, notably from the wine, tourism, and real estate sectors, began arriving. Significant investments have materialized in Valle de Guadalupe, featuring small and large wine estates owned by Mexican and foreign proprietors, establishing themselves in the region to promote accommodation, gastronomy, or nightlife entertainment businesses, as well as investing in companies that merge wine production with tourist services— such as El Cielo, Maglén, or Bruma—that require different land uses (N. L. Bringas-Rábago, field diary, December 15, 2022).

A CONCEPTUAL APPROACH TO TRUST NETWORKS AND TYPES OF MECHANISMS

The observed changes in Valle de Guadalupe prompt both theoretical and practical inquiries regarding future land uses and the available options for dealing with increasingly contentious social interactions. This section aims to provide a brief overview of the theoretical-conceptual foundations of trust networks and the mechanisms used by them in relation to territorial conflicts. The explanatory proposal is based on the analysis of these networks and the action repertoires used by various social actors to address conflicts and attempt to achieve consensus regarding land use management during the period between 2000 and 2020.

Perspectives on Trust Network Analysis

Historically, trust networks have been used for multiple purposes, with conflict management standing out as a primary function. Trust itself emerges from ongoing interaction and interpretation processes. The relational approach provides various elements that help understand the connection between trust networks and the trajectory of conflict management regarding land use; likewise, it enables the analysis of cooperation as a process rooted in the intersubjective interpretation of the actions of those involved in particular circumstances. This approach delineates the logic governing the establishment and functioning of these networks, offering insights into the development of trust within interpersonal relationships across diverse contexts (Hanagan & Tilly, 2010; Marcuse, 2010; Tilly, 2005).

According to McPherson et al. (2001), individuals naturally form connections, based on various factors such as physical appearance, interests, preferences, common goals, benefits, etc. A phenomenon often termed as homophily. Expanding on this concept, Ramírez de la Cruz and Gómez (2016) define this social behavior as a network of strong ties that connects groups or subgroups whose members share similar characteristics and are bound by bonds of trust.

Trust, viewed in this context, extends beyond being merely an attitude or perception individuals hold toward others. Placing trust in someone entails an inherent risk, primarily the vulnerability to potential deception (Tilly, 2005). Therefore, before extending trust, an individual must evaluate information about the other person, assessing whether they are indeed worthy of establishing bonds built upon trust.

Indeed, trust motivates network members to interact continuously (Coleman, 1990). Despite the underlying uncertainty in risky situations, members will intensify their interactions to keep the network active, as its existence, commitment, and reliability among its members depend greatly on it (Hardin, 2001). Building relationships based on commitment not only benefits the organization but also fosters collective mobilization in social, cultural, and political spheres, enabling its survival and expansion (Yamagishi & Yamagishi, 1994).

A problem that arises when analyzing trust networks is how to transition from actor-centered explanations—the rational approach—towards the connections that facilitate cooperation under institutional arrangements—the institutional approach—to reach dynamic interaction processes based on learning. The institutional approach is mainly characterized by action frameworks in which actors undertake various participatory tasks, allocate resources to achieve their goals, and devise strategies in response to contingent events. Normative references for social interaction, therefore, take place within institutional frameworks (Emirbayer, 2009; Ostrom, 2011; Uribe, 2009).

To address this analytical challenge, the relational approach (Emirbayer, 2009; Pierson & Skocpol, 2008; Shaffer, 2018; Uribe, 2009) offers insights into studying the intricate causal mechanisms behind contentious events within specific historical contexts of cities, regions, or countries. This viewpoint perceives society as an intricate network of relationships characterized by dynamic interactions and participatory elements (Emirbayer, 2009). In the contemporary relational perspective, trust networks hold significance in comprehending developmental processes across various scales, as the connections forged between individuals lay the foundation for operational and functional social structures.

Authors like Ledeneva (2004), Levi and Stoker (2000), Putnam (1993), Seligman (1998), Yamagishi and Yamagishi (1994), and Tilly (2005) point out that analyzing relationships based on trust is important for understanding participatory dynamics in discussing public issues, as these are part of social, economic, and political interactions. Moreover, these studies foster reciprocal work commitments by maintaining channels of horizontal interaction at community, democratic, or local policy levels (Putnam, 1993).

Conceptualization and Characterization of Trust Networks

Among the contributions made to understanding trust networks, Tilly’s proposal (2005) is particularly useful in explaining conflicts over land use in Valle de Guadalupe. In his book ‘Trust and Rule,’ Tilly (2005) develops a conceptualization of network functioning, delving into the constituent and operational elements of these networks in detail. His argument offers a framework for investigating and deeply exploring the reasons why these networks are considered unique and distinctive within broader social structures.

Trust networks, as connections or relationships between individuals, contribute to forming strong bonds that possess particular characteristics of significant collective scope and are distinguished by the close relationship among their members (Tilly, 2005). These networks are delineated by the utilization of valuable collective resources—such as time, capital, or capabilities—that each member contributes toward achieving shared goals. Notably, these collective efforts aimed at fostering trust possess a distinctive trait setting them apart from other forms of social interaction: their endurance and continuity over time.

A trust network can originate from something as simple as a friendship, a professional relationship with a colleague, or those who share the same interests. As these connections deepen, relationships progress to higher levels of trust through repetitive interactions and innovative engagements. This learning process fosters the emergence of a prototype of relationship-commitment connections, strengthening ties that enable the exchange of resources and broader collaborative actions (Hanagan & Tilly, 2010).

In such networks, each member is aware of the benefits, rights, and obligations they hold towards their peers, alongside a clear understanding of the group’s pursued objectives, fostering a deep commitment and close interaction. Trust networks thus emerge, possessing substantial capabilities beyond mere relationships, allowing them to effectively address, stabilize, and serve both internal and external interests (Krinsky & Mische, 2013; Tilly, 2005).

Authors such as Wasserman and Faust (1995), and Lozares (1996), aligning with Tilly (2005), highlight three key characteristics that differentiate trust networks from traditional networks:

They foster a heightened level of interaction among members, nurturing closer bonds and facilitating the organic emergence of collective trust.

Members within these networks employ mechanisms to mitigate potential risks, particularly in engagements with external networks, bolstering the foundations of trust.

Commitment stands out as a defining attribute within trust networks, enabling social actors to operate across micro and macro levels while continuously reinterpreting the relationships forged through these interactions (Ledeneva, 2004).

Trust networks play a pivotal role in discussions surrounding public interest matters, particularly within open structures within the State. These frameworks facilitate participative avenues, transactions among actors, and operational mechanisms for addressing and resolving contentious processes. Krinsky and Mische (2013) underscore the involvement of networks grounded in trust and commitment in resolving social problems. Over time, the cumulative ties within these networks translate into actions that significantly influence public policy issues, often serving as a “survival kit” (Ledeneva, 2004, p. 12), addressing common network goals or compensating for governmental deficiencies. However, instances of corruption or misconduct among participants in debates or contentions tend to generate a ripple effect of distrust within these networks (Petersen Cortés, 2023).

In short, trust networks operate as conduits for various resources that allow them to compensate for shortcomings of central authorities, yielding significant impacts within the social sphere. As Hanagan and Tilly (2010) indicate, in addition to possessing capabilities and strength in their relationships, trust networks serve as catalysts for transformative changes. They possess the capacity to instigate reforms within the socio-territorial environment where they operate, exerting influence over land use policy decisions.

Key Categories for the Study of Trust Networks

When analyzing trust networks, it’s important not to lose sight that their formation and evolution stem from individual actions occurring within specific contexts. The intersubjective perception of individuals can either foster or hinder the development of trust relationships. An issue for empirical research is distinguishing the dimensions of trust and the type of indicators to consider in determining the presence of such networks.

Based on Tilly’s work (2005), three key categories stand out for analysis:

Mechanisms for building trust relationships: According to Hardin (2001), these relationships are established through incentives, encapsulated interests, or, as noted by Yamagishi and Yamagishi (1994), continuous reciprocal interactions. Coleman (1990) also suggests that the establishment of trust bonds involves a cost-benefit analysis, potentially impacting the relationship.

Engagement in activities: Networks enable the accomplishment of significant long-term actions; as long as the group exhibits this characteristic of “transcendence” it will be an indicator of high levels of trust.

Communication strategies: Utilizing horizontal communication channels within networks ensures a homogeneous flow of information among members, leading to better acceptance of information, consensus-building, and coordinated actions among participants.

To address the empirical challenge of analyzing trust networks, Tilly (2005) proposes the following: First, identify close, frequent, or reciprocal connections among group members. Networks with stronger trust relationships will exhibit commitment and responsibility among their members when undertaking an activity. Second, examine the type of activities they engage in based on the well-being incentives they provide to their members. The resources invested in each task (time, capital, or capabilities) will define the significance and scope of these actions. Third, recognize that external communication strategies outside the network relate to the connections and level of dialogue with other networks, cooperative enterprises, or policy agents. If trust is high when engaging with an external agent, its members will play an active role and, consequently, share responsibilities, thus creating different collaborative mechanisms determined by the context and the interests each pursues.

The conclusion drawn from this review suggests that collaboration between the government and trust networks involves negotiating or embracing shared responsibilities, the scope and achievements of which can vary depending on the availability of resources, which may also fluctuate over space and time (Alexander et al., 2004; Putnam, 1993; Tilly, 2005).

In a broad sense, the shortcomings within formal systems make networks a means to address and fulfill various needs. However, trust networks do not replace government public action; while they serve as a means to access resources, their capacity to act as compensatory networks is limited by a variety of situations that are worth investigating in the future (Ledeneva, 2004).

Types of Collaborative Mechanisms

When examining the external links of trust networks, it’s essential to recognize that these networks compete for resources—such as capital, land, and labor—with other actors. This means that, in practice, individuals and groups are forced to develop strategies to deal with new networks and ensure their permanence within the social system (Tilly, 2005). In this sense, trust networks operating in contexts where there’s contention for access to and control of these resources create scenarios of inequality in their distribution and management.

The previous review suggests that the expected role of trust networks may vary depending on the interaction among its members, as well as between the agents and government organizations. However, it mainly relates to the relational mechanisms that are significant and recurring for understanding these interactions.

Table 1 illustrates the articulating mechanisms between trust networks and the government, delineating various participation practices within these networks. The vertical axis reflects the objectives set by the government in its collaboration with the networks. On the horizontal axis are the practices adopted by networks in their engagement with the government or other networks. The table employs traffic light colors to denote the levels of trust associated with each mechanism: green denotes actions constituting and revealing higher levels of trust, yellow signifies potential for establishing trust relationships, and red indicates situations where trust is absent.

Table 1. Articulating mechanisms in the relationship between trust networks and government for conflict management

Source: Own elaboration based on Tilly (2005).

The government establishes three possible objectives for collaboration with trust networks: integration/strengthening, negotiated coexistence, and segregation. With the first objective, the government seeks to establish reciprocal relationships with the networks, demonstrating high trust and low levels of uncertainty (Heimer, 2001). With the second, the relationship involves negotiated participation where both parties contribute resources (goods, capital, and information) to achieve a particular goal (Lozares, 1996; Tilly, 2005). The third objective, segregation, triggers relationships that damage trust and sets the stage for confrontations to emerge.

Table 1 proposes nine dominant types of mechanisms resulting from the interaction between networks and government, which can signify scenarios of either confrontation or consensus. This work focuses on developing three of these mechanisms: participatory innovation, clientelism/avoidance of responsibilities, and discretionary appropriation. The theoretical significance of these mechanisms lies in understanding the management of territorial conflicts, as observed in Valle de Guadalupe during the studied period. These mechanisms manifest through the active participation of network members and the specific practices adopted within a given context.

The first mechanism, called participatory innovation, refers to the outcome of an active interaction among its members that allows for the integration or strengthening of trust relationships with external networks and the government. This operates under exercises of commitment and trust, considered key factors for maintaining reciprocal interactions (Heimer, 2001; Tilly, 2005).

The second mechanism is clientelism/avoidance of responsibilities, where network participation operates under an exchange dynamic. In other words, participation will cost the network the use of its resources, but it ensures the achievement of the pursued objective (Auyero & Benzecry, 2016; Tarapues Taimal, 2012). Trust in this mechanism can increase or decrease depending on the outcome of the collaboration or the incentives that sustain it (Hardin, 2001; Yamagishi & Yamagishi, 1994).

Finally, the mechanism of discretionary appropriation presents a scenario opposite to participative innovation, where the trust relations between networks and government are nonexistent, the interest in undertaking activities is conditioned by previous experiences, and communication strategies are completely limited or isolated (Tilly, 2005).

The previously proposed mechanisms allow us to observe the possibility for trust networks and governments to move towards the recurrent use of action repertoires that contribute to consensus in managing resources amidst pressures to change land use. It also leaves open the possibility of experiencing regressive processes in reaching agreements. In this sense, this approach directs attention to relevant aspects of collective actions and their mechanisms to understand scenarios of dispute and confrontation in the territory. It observes how they participate, relate, and what strategies are used in these scenarios.

METHODOLOGICAL STRATEGY FOR THE ANALYSIS OF TRUST NETWORKS

To study how trust networks have operated in Valle de Guadalupe regarding the territorial conflicts observed from 2000 to 2020, a qualitative methodology was chosen to obtain perceptions and interpretations of the actors involved in the contentious events (Barragán et al., 2008). To do so, a review of press coverage was conducted initially, allowing for the identification of the parties involved and the type of involvement they had during disputes over land use.

Semi-structured interviews were used to gather detailed information regarding the participation of actors in pre-existing networks, aiming to collect evidence about the mechanisms employed by the actors in their interaction dynamics and the progress made in negotiations (Halperin & Heath, 2012). The design of this instrument incorporated topics concerning collaborative actions (formal and informal) envisioned by the networks regarding the future of this region and the government’s involvement in the long-term regulation of the territory.

Non-participatory observation was another technique used to observe interviewees’ behaviors concerning other actors, conflict situations, or any other topic related to collective participation. The snowball technique was used for this purpose (Voicu & Babonea, 2011). This tool allowed reaching new actors who were not initially identified, thereby increasing the number of informants. It’s worth mentioning that the COVID-19 pandemic prevented in-person approaches with informants, so alternatives like video calls were sought to gather the necessary information.

From a theoretical foundation, an analytical framework was formulated to discern collaborative patterns and mechanisms within contexts of contention. To achieve this, the following categories, inspired by Tilly’s work (2005), were established: a) types of relationships, based on the periodicity and reciprocity of the links observed; b) transcendental activities, reflecting both internal and external network participation with other entities; c) communication strategies, derived from dialogues and consensus among actors concerning changes in land use.

Part of the research objectives aims to elucidate the strategies and primary mechanisms utilized by trust networks within contentious scenarios to attain a shared objective, supported by associated evidence. The participative innovation mechanism encompasses evidence depicting actions characterized by trust and reciprocity among network members. Conversely, the clientelism mechanism encompasses actions where trust networks engage to secure direct benefits or incentives for their members. Lastly, the discretionary appropriation mechanism entails activities displaying contention between networks and the government or situations where trust was absent.

To organize and analyze the information, the Atlas.ti software was employed. A total of 14 interviews underwent systematic categorization, with codes established for various dimensions of trust networks: transcendent activities, internal network communication, trust relationships, mutual commitments, and external connections. Through coding, actors were classified into distinct groups: leading, active, and incidental, and their affiliations were identified, including government, civil society, winemakers, farmers, and/or landholders. Notably, due to uncertainties prompted by the pandemic, interviews with three identified actors could not be conducted, despite their identification via the snowball technique.

Given the intricate nature of studying trust networks and comprehending the perspectives of involved parties, a content analysis was conducted using Atlas.ti codes. This approach offered a clearer insight into relationships, participatory action, and the meanings conveyed by the actors (Fernández, 2002). Word association helped identify evidence of actions linked to different mechanisms, enabling the establishment of relationships between these mechanisms and active networks in Valle de Guadalupe. For example, in the case of clientelism, associations were found with words describing intentional efforts to construct and maintain local power, employ actions for control, social cohesion, and intimidation (Boesten, 2014). To ensure objectivity and mitigate biases in the analysis, the scope of each category was precisely defined. Despite research challenges posed by the pandemic, sufficient information was obtained through successful interviews with key actors from identified groups, enabling fulfillment of the outlined analytical framework.

RESULTS ANALYSIS: TRAJECTORIES AND COLLABORATIVE MECHANISMS

This section presents the research findings. It begins by analyzing the collaborative trajectories of diverse groups coexisting in Valle de Guadalupe, followed by an exploration of mechanisms defining various forms of collaboration among these actors. Furthermore, it identifies the contentious scenarios related to land use and delineates the mechanisms governing the relationship between trust networks and the government in managing territorial conflicts.

Collaborative Trajectories of Trust Networks

The initial trust networks in Valle de Guadalupe date back to the late 20th century. This period witnessed the rise of new social actors, including wine agribusiness entrepreneurs, farmers, laborers, and migrant families forming groups. They recognized the valley as a potential source for employment and production, focusing on grape, olive, and vegetable harvesting (Santiago, 1999).

During these years, actors actively fostered relationships, especially to address actions related to land use, which is understandable considering the region’s early development. At that time, there was no official planning instrument, but there was an interest from viticulturists in the agricultural vocation of land use (State Executive Branch Agreement 37 of 2006).

In its initial phase, the focus was primarily on fostering agricultural development, particularly in viticulture, which significantly contributed to the expansion of vineyards and wine production (Magoni, 2009). Subsequently, around the year 2000, the formation of small groups dedicated to wine production became evident, enhancing the capabilities within the wine sector.

During this period, both public and private sectors collaborated to establish the ‘Ruta del Vino de Baja California,’ resulting in increased involvement of actors in this region and the acquisition of spaces for the development of new wine ventures, restaurants, hotels, and vacation properties (Quiñónez Ramírez et al., 2012). As the region transitioned from primary to tertiary activities, collectives emerged to deliberate and establish legal frameworks aimed at regulating the region’s expansion.

Use of Collaborative Mechanisms in Trust Networks

The analytical strategy used facilitates tracing the evolution of mechanisms employed to bolster the wine industry and the subsequent emergence of a sequence of conflictual events that commenced in 2003. It was considered that from that year, a period of circumstantial exchange began in the formation of trust networks due to the proliferation of events and decisions intensifying divergent stances concerning alterations in land use. The results of the three mechanisms implemented by the trust networks in Valle de Guadalupe are presented below (see table 2).

Table 2. Collaborative mechanisms used by trust networks and government actors

| Mechanisms operated by networks |

Participatory scenarios | Actors involved | Objective of the government-network relationship |

Collaborative patterns |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participatory innovation |

2003. Publication of Land Use Guidelines (Directrices para el Uso del Suelo…) and creation of the collective Por un Valle de Verdad |

Winegrowers, academics and state government. |

Integration / strengthening |

Reciprocal relationships and commitment attitude |

|

| 2006. Publication of the Regional Ecological Planning Program (Programa Regional de Ordenamiento Ecológico…) and the Wine Region Regional Development Program (Programa de Desarrollo Regional Región del Vino) |

SEFOA, state government, winegrowers, local population, ejidatarios |

||||

| 2010. Publication of the Sectoral Program (Programa Sectorial…) |

FONATUR, municipal government, winegrowers, local population, and ejidatarios. | ||||

| 2018. Update to the Zoning and Land Use Regulation (Reglamento de Zonificación y Usos de Suelo...) |

Public agencies, winegrowers, ejidatarios. |

||||

| 2019. Approval of the Zoning and Land Use Regulations (Reglamento de Zonificación y Usos de Suelo…) |

Provino,6 winegrowers,

Por un Valle de Verdad collective, local population. |

||||

| Clientelism and evasion of responsibility |

2013. Adjustment to the Sectoral Program |

Public servants and real estate developers |

Negotiated coexistence negociada |

Participation is conditioned by the incentive of engagement (exchange) |

|

| Discretionary appropriation |

2013. Proposal to modify the Sectoral Program |

Winegrowers, Por un Valle de Verdad collective, and municipal government |

Segregation | Concealment and participatory exclusion |

|

| 2019. Opposition to the approval of the Regulation |

Ejidatarios of El Porvenir | ||||

| Higher trust | |||||

| Potential to establish trust relationships | |||||

| No trust | |||||

Source: Own elaboration based on the analysis of the results (Agreement 32 of 2003; State Executive Branch Agreement 37 of 2006; State Executive Branch Agreement 44 of 2010; State Executive Branch Agreement 42 of 2018, City Council Agreement 61 of 2019; Cervantes, 2013;García, 2013; SEDESOL, 2006; Valenzuela, 2013; A. De la Torre, personal communication, 2 de abril de 2020; R. Romo, personal communication, March 20, 2020).

-

Participatory Innovation

The presence of this mechanism can be traced back to August 2003 when the Dirección de Ecología Municipal de Ensenada issued a permit for the installation of a gas plant in Valle de Guadalupe, sparking outrage among residents and winegrowers (Luna González, 2003). It’s worth noting that in July of the same year, the Directrices Generales del Uso de Suelo (General Land Use Guidelines) for this region were published, which were the only official planning instrument available at that time (Agreement 32 of 2003).

The result of this mobilization of trust networks culminated in the cancellation of that proposal, giving rise to the emergence of the social movement Por un Valle de Verdad (A. De la Torre, personal communication, April 2, 2020). Participants engaged in this dispute transitioned their activism towards issues centered on land use regulation, expanding their spectrum of actions by road closures, occupying public facilities, and advocating for the annulment of harvest events (Vargas, 2003).

A year later, Hugo D’Acosta founded the Estación de Oficios El Porvenir, known as “la escuelita”, at the request of some friends who wanted to make wine (Maceiras, 2018). This endeavor created collaborative opportunities, enabling landowners to pivot towards wine production following the conclusion of grape purchase contracts, fostering knowledge transfer among networks related to viticulture (Cuéllar, 2016).

By the year 2006, several trust networks participated in the public consultation processes concerning the Ecological Zoning Programs and the Regional Development of the Wine Region [Programas de Ordenamiento Ecológico del Corredor San Antonio de las Minas-Valle de Guadalupe] (State Executive Branch Agreement 37 of 2006) and Desarrollo Regional Región del Vino (SEDESOL, 2006). Through dynamics characterized by mutual commitment and effective communication strategies, consensus-building among actors was facilitated throughout the planning phase. As a result, a regional subcommittee was established, comprising civil associations, ethnic groups, academics, settlers, and representatives from all three levels of government.

During 2010, the government of the state of Baja California and the National Fund for Tourism Development (Fondo Nacional de Fomento al Turismo [FONATUR]) created the Sectoral Program for Urban-Tourist Development of the Viticulture Valleys (Programa Sectorial de Desarrollo Urbano-Turístico de los Valles Vitivinícolas de la Zona Norte del Municipio de Ensenada) (State Executive Branch Agreement of 2010). However, this program, primarily oriented towards tourism, omitted the inclusion of the ejidal aspect governed by federal agrarian law, and neglected the critical issue of water management. Consequently, this omission triggered significant controversy among the local community, government entities, and viticulturists (J. Sandoval, personal communication, April 20, 2020).

In 2018, the municipal authority revised the Sectoral Program in collaboration with ejidatarios,4 viticulturists, and public agencies. This reformulation incorporated comprehensive development guidelines concerning water management, landscape preservation, community involvement, and agricultural aspects that were initially omitted (City Council Agreement 61 of 2019). It’s essential to highlight that, since the program’s initial publication, the establishment of regulations to implement the program’s directives has remained pending.

In 2019, towards the end of Mayor Gerardo Novelo Osuna’s administration (2016-2019), viticulturists, the collective Por un Valle de Verdad, a representative from indigenous communities, and the gastronomic sector collaborated extensively and engaged in committed activities to secure the approval of this regulation (Flores, 2019). The concerted efforts of these trust networks, in conjunction with the municipal administration, yielded a substantial impact, culminating in the long-awaited regulation’s approval and subsequent publication in the Official Gazette of Baja California (City Council Agreement 61 of 2019).

For viticulturists, the approval of the regulation signified a notable milestone in establishing a legal framework to oversee the swift expansion of this region. Additionally, it posed a challenge for future administrations, tasking them with fostering ongoing participation, dialogue, and diligent oversight to ensure full compliance with this regulation (H. Backoff, personal communication, March 25, 2020; F. Pérez, personal communication, March 31, 2020).

-

Clientelism and Evasion of Responsibilities

In 2013, a pivotal event showcasing this mechanism unfolded when a consortium of real estate developers and public officials proposed an exclusive arrangement to amend the 2010 Sectorial Program (State Executive Branch Agreement 44 of 2010). This proposal aimed to pave the way for a residential-tourist venture, directly conflicting with the objectives of winemakers, who were advocating for the preservation of agricultural zones (Cervantes, 2013; Olvera, 2003; Valenzuela, 2013). Although the proposal was eventually retracted, its emergence caused unease and dissatisfaction among trust networks, sparking mistrust toward governmental actions altering land use and generating a sense of complete distrust towards these actors (N. Badán, personal communication, April 25, 2020; F. Pérez Castro, personal communication, March 31, 2020).

-

Discretionary Appropriation

Meanwhile, alongside the aforementioned interactions, there were other instances where low levels of trust were observed. This mechanism’s use became particularly evident in the proposed modification of land use in the 2010 Sectoral Program. This sparked outrage among existing networks of trust, as the proposed modification allowed for the construction of housing, hotels, and commercial spaces (García, 2013). Despite effectively preventing this initiative, the municipal government’s actions involving segregation and favoritism towards real estate developers resulted in a decline of trust among the populace (R. Romo, personal communication, March 20, 2020).

Under this mechanism, another event occurred in 2019: the networks of ejidatarios expressed opposition to the approval of the Zoning and Land Use Regulation (Reglamento de Zonificación y Usos del Suelo) for this region, as this group is governed by the Agrarian Law (Decree of 1992; Vargas, 2019). This led to their protest before the municipal government: the resolution favored compliance with the legal framework, which was considered an exclusionary practice by this group (R. Romo, personal communication, March 20, 2020).

Despite previously sharing a developmental vision for Valle de Guadalupe with viticulturists (J. Sandoval, personal communication, April 20, 2020), the opposition from ejidatarios stemmed from the constraints imposed by the Regulation on their lands5 (V. Bravo, personal communication, March 20, 2020; R. Romo, personal communication, March 20, 2020). Their stance also reflected a rentier focus, given that only around 30 to 40% of current ejidatarios still retain their lands, while others opted to sell them. This pattern indicated actions veiled in collaboration, diminished trust levels, and exclusionary practices (V. Bravo, personal communication, March 20, 2020). This situation raised doubts about the strengthening of extensive networks capable of influencing public decisions (Cervantes, 2021). These observations confirm a lack of commitment to collective interests. Additionally, they reveal a deterioration in relationships among networks, rendering them susceptible to exploitation or potential dissolution (Tilly, 2005).

Based on the evidence presented above, it’s apparent that the networks of trust within the winemaking community and the Provino committee have actively chosen to strengthen their relationships with the current government for the oversight of pending tasks. This recent trend signals a renewed utilization of participatory innovation mechanisms, potentially fostering increased trust levels between these entities and the governing bodies (H. Backoff, personal communication, March 25, 2020; F. Pérez, personal communication, March 31, 2020).

The conflicts arising from land use changes in this region have necessitated, as highlighted by Hardin (2001), the implementation of incentives to encourage participatory actions. These actions, extending beyond mere relationships, have cultivated substantial capacities to address not only internal interests but also align with public policy objectives (Krinsky & Mische, 2013; Tilly, 2005).

Additionally, there’s an observed shift among ejidatarios, the local populace, and viticulturists, transitioning from actions driven by mutual commitment to confrontations regarding land use changes (Espejel, 2022; Rodríguez, 2019; Valenzuela, 2013). This shift is partly attributed to inadequate communication channels managed by previous administrations, ambiguous procedures, and technical mishandling in programs. These factors have led to an evasion of responsibilities and a lack of active engagement within the networks (Putnam, 1993; Tilly, 2005).

CONTENTION AND USE OF COLLABORATIVE MECHANISMS: ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION

The intersecting interests driving the structural transformation of Valle de Guadalupe have generated underlying tensions surrounding the utilization of collaborative mechanisms to address land-use challenges. Conflicts have arisen due to the adoption of non-transparent procedures in applying land-use regulations, sparking disputes among diverse stakeholders in this region. Presently, these conflicts predominantly involve the real estate and service sectors, aggravated by the absence of well-defined regulations governing land use. As a result, interest groups are mobilizing, exerting pressure on municipal authorities to intervene and establish guidelines to manage this uncontrolled growth.

The trust networks are diverging in their trajectories. Initially marked by reciprocity, the relationships between winegrowers and landowners took a different turn with the arrival of new real estate players and wine tourism companies, resulting in the acquisition of ejidal lands by these entities. This shift impacted collaborative relationships and disrupted the original vision for the future of the wine region. Contrary to the relationship-commitment prototype suggested by Hanagan and Tilly (2010), the envisioned level of commitment in relationships was not attained. This limitation hindered the progression of relationships to higher levels of trust, subsequently diminishing the frequency and intimacy of their interactions.

Similarly, there was a loss of trust in the government due to its inability to enforce legal frameworks and to provide continuity in territorial policies. This led to confrontations between networks and the government and increased uncertainty by weakening the credibility of the latter. Conversely, winegrowers, the collective Por un Valle de Verdad, and the Provino committee managed to strengthen their bonds, increase their levels of trust, and enhance their capabilities. This wouldn’t have been possible without the trust, resources, and ongoing interactions among their members (Coleman, 1990; Hardin, 2001).

This prompted the networks to resort to employing mechanisms to collaborate with the government or other networks. It’s essential to note that these mechanisms are contingent upon the specific context and the nature of the relationships in which they evolve. It is worth emphasizing the evolutionary nature of networks, and to showcase their progression toward more or less collaborative action repertoires in their interactions with the government.

The evolving context has facilitated networks in adopting diverse mechanisms tailored to their specific situations and interests. This adaptation has given rise to a participatory model based on incentives (Hardin, 2001). A clear example of this participative innovation mechanism can be observed in viticulturist networks, in Por un Valle de Verdad, in Provino, and in the local population, who have shown increased collaboration with the government over time, inclusive of academic groups (S. Cosío, personal communication, April 28, 2020). This resonates with Tilly’s (2005, p. 25) concept of the “dispositional line,” wherein trust networks exhibit a readiness for collaboration and engagement with external entities, fostering increased trust for future endeavors and enabling broader actions (Coleman, 1990).

Likewise, trust networks require incentives to continue operating with innovative mechanisms that allow the development of capacities to drive the creation of public policies, such as the case of the approval of the Zoning Regulation (City Council Agreement 61 of 2019).

In the context of clientelism/evasion of responsibilities, there’s been minimal utilization of these mechanisms within trust networks; however, certain real estate and tourist groups have employed them in collaboration with local government entities. The relationships established between these groups were conditioned by incentives, entailing a cost in the exchange of resources to alter the Sectoral Program. This unveiled a segregation from other networks and the manipulation of procedures that ought to have undergone public consultation. The revelation of hidden interests behind such modifications undermined the trust previously held by existing networks towards the government. This occurrence affirmed the notion that bestowed trust can indeed be betrayed, echoing Tilly’s (2005) observations.

In relation to the discretionary appropriation mechanism, the findings suggest that while the group of ejidatarios represents one of the oldest networks in Valle de Guadalupe, their collaborative efforts with other networks, particularly viticulturists, remain limited. They perceive viticulturists as a network favored by the government (R. Romo, personal communication, March 20, 2020). This perception has led to their opposition toward the Zoning Regulation, impeding progress or engagement in participative innovation mechanisms, thereby straining pre-existing and long-standing connections (Tilly, 2005). The network of ejidatarios has displayed inconsistent trust-building processes, both with the municipal government and viticulturists, resulting in their reputation as an unreliable network, stemming from their involvement in subdividing and selling agricultural land for alternative purposes.

The government’s involvement in collective dynamics is perceived as unstable and unreliable by both viticulturist and ejidatario networks. Furthermore, instances of corruption have proliferated, fostering widespread distrust (Petersen Cortés, 2023). Simultaneously, the uncertainty surrounding short governmental terms raises concerns regarding political agendas, particularly concerning the organization of Valle de Guadalupe (F. Pérez Castro, personal communication, March 31, 2020). Lastly, it’s worth noting that the capacities of municipal governments have been constrained by resources and limited by the duration of governmental periods. Nevertheless, trust networks have operated as a vital survival mechanism (Ledeneva, 2004; Krinsky & Mische, 2013).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The trust network perspective helps to comprehend how the array of networks and interests converging in Valle de Guadalupe, has generated conflicts regarding the immediate benefits stemming from tertiary activities and real estate development. These conflicts extend beyond the traditional activities in the region, such as viticulture, which has long defined the territorial identity of Valle (N. Badán, personal communication, April 25, 2020).

The management of conflicts arising from changes in land use has proven to be complex. In this regard, it is observed that trust networks have diligently operated within a governmental regime that was previously absent, relying on isolated participatory mechanisms (N. Badán, personal communication, April 25, 2020; H. Backoff, personal communication, March 25, 2020; F. Pérez Castro, personal communication, March 31, 2020).

Evidence used here suggests that in recent years, the collaborative mechanisms between networks and government have transitioned towards levels of integration and participatory innovation, representing significant progress in fostering dialogues, reaching consensus, and instigating actions aimed at resolving territorial conflicts or as a means to design public policies that enhance comprehensive participatory exercises.

Theoretically, trust networks can be perceived not only as a grouping of actors but also as instruments for participatory planning or as catalysts for collective objectives. Besides serving as overseers of a territory’s resources, they facilitate agreements or viable solutions to resolve social, political, and economic conflicts.

A limiting factor hindering the participation and engagement of trust networks in Valle de Guadalupe is the management of procedures and technicalities involved in programs and regulations (J. Sandoval, personal communication, April 20, 2020). The studied dynamics have fostered collaboration but have also led to notable confusion and distrust among the local population and ejidatarios when undertaking significant activities with other actors.

In practice, trust networks have dealt with conflicts related to land use and have confronted the inefficiencies or shortcomings of local administrations. However, one of the main challenges these networks face is the ability to process the acquired learning to enhance the management of contentious situations and disputes that may arise in the territory. Failure to assimilate this learning could compel these networks to deviate from actions rooted in trust and the pursuit of collective goods, towards exercising actions of concealment and participatory exclusion (Tilly, 2005; Hanagan & Tilly, 2010).

By analyzing three mechanisms employed by trust networks in Valle de Guadalupe, this article showcased their capacity to either tip the balance towards higher and improved levels of cooperation or towards irresolvable conflicts among interest groups competing for short-term benefits. Nonetheless, for a better understanding of the diverse mechanisms employed by these trust networks, more extensive studies are warranted. These studies should delve into their operational dynamics and participation in conflict resolution.

The case of Valle de Guadalupe underscores the significance of investigating trust networks as dynamic contributors within conflicts. This line of research and analysis holds the potential to offer substantial contributions benefiting communities, enhancing governmental efficiency, and bolstering the efficacy of networks as tools for planning and preserving the natural and cultural heritage of this region, as well as others across Mexico and globally.

REFERENCES

Acuerdo 32 de 2003 [Secretaría General de Gobierno]. Mediante el cual se aprueba la publicación de las Directrices Generales del Uso de Suelo de las Localidades de Santa Rosaliíta, Bahía de los Ángeles, San Luis Gonzaga y del Valle de Guadalupe del Municipio de Ensenada, B. C. 11 de julio de 2003. https://bit.ly/46dRLp2 [ Links ]

Acuerdo 37 del Poder Ejecutivo Estatal de 2006 [Secretaría General de Gobierno]. Por el que se aprueba el Programa Regional de Ordenamiento Ecológico del Corredor San Antonio de las Minas-Valle de Guadalupe. 8 de septiembre de 2006. https://bit.ly/479Hf3G [ Links ]

Acuerdo 42 del Poder Ejecutivo Estatal de 2018 [Secretaría General de Gobierno]. Mediante el cual se aprueba la Actualización del Programa Sectorial de Desarrollo Urbano-Turístico de los Valles Vitivinícolas de la Zona Norte del Municipio de Ensenada. 14 de septiembre de 2018. https://bit.ly/3MIRR1c [ Links ]

Acuerdo 44 del Poder Ejecutivo Estatal de 2010 [Secretaría General de Gobierno]. Mediante el cual se aprueba el Programa Sectorial de Desarrollo Urbano-Turístico de los Valles Vitivinícolas de la Zona Norte del Municipio de Ensenada, Baja California. 15 de octubre de 2010. https://bit.ly/40AdXZw [ Links ]

Acuerdo 61 de Cabildo de 2019 [H. XXII Ayuntamiento Constitucional de Ensenada, B. C.]. Mediante el cual se aprueba la creación del Reglamento de Zonificación y Usos de Suelo para el Programa Sectorial de Desarrollo Urbano-Turístico de los Valles Vitivinícolas de la Zona Norte del Municipio de Ensenada (Región del Vino), B. C. 13 de diciembre de 2019. https://bit.ly/3QyzJIx [ Links ]

Alexander J. C., Marx, G. T. y Williams, C. L. (2004). Self, social structure and beliefs: Explorations in sociology. University of California Press. [ Links ]

Auyero, J. y Benzecry, C. (2016). La lógica práctica del dominio clientelista. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales, 61(226), 221-246. https://bit.ly/3MIQzDf [ Links ]

Barragán, R. (Coord.), Salman, T., Ayllón, V., Córdova, J., Langer, E., Sanjinés, J. y Rojas, R. (2008). Guía para la formulación y ejecución de proyectos de investigación. Fundación PIEB. [ Links ]

Boesten, J. (2014). La generalización de la confianza particularizada. Paramilitarismo y estructuras de confianza en Colombia. Colombia Internacional, (81), 237-265. http://dx.doi.org/10.7440/colombiaint81.2014.08 [ Links ]

Bringas-Rábago, N. L. (Coord.). (2014). Las Fiestas de la Vendimia y el turismo enológico. Boletín del Observatorio Turístico de Baja California, (12), 1-12. https://bit.ly/3mIfgpz [ Links ]

Bringas-Rábago, N. L. y Toudert, D. (2011). Atlas. Ordenamiento territorial para Baja California. El Colegio de la Frontera Norte. [ Links ]

Cervantes, J. (23 de mayo de 2021). La invasión en ciernes en el Valle de Guadalupe. Proceso. https://bit.ly/3JKWXYg [ Links ]

Cervantes, S. (21 de octubre de 2013). Rechazan modificación en uso de suelo en BC. El Economista. https://bit.ly/3ZrtSXJ [ Links ]

Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Cuéllar, M. (12 de septiembre de 2016). Cumple 15 años la “escuelita” que cambió la vinicultura de Ensenada. La Jornada Baja California. https://www.jornada.com.mx/2016/09/12/estados/030n1est [ Links ]

Decreto de 1992 [con fuerza de ley]. El Congreso de los Estados Unidos Mexicamos decreta la Ley Agraria. 26 de febrero de 1992. Diario Oficial de la Federación núm. 18. https://n9.cl/ndcd [ Links ]

Emirbayer, M. (2009). Manifiesto en pro de una sociología relacional. Revista CS, (4), 285-329. https://doi.org/10.18046/recs.i4.446 [ Links ]

Espejel, I. (7 de septiembre de 2022). Salvemos el escaso suelo fértil del Valle de Guadalupe. Nexos. https://bit.ly/3St6yqN [ Links ]

Fernández, F. (2002). El análisis de contenido como ayuda metodológica para la investigación. Ciencias Sociales, 2(96), 35-53. https://bit.ly/41v6FW5 [ Links ]

Flores, M. (28 de septiembre de 2019). Aprueba Cabildo de Ensenada Reglamento de Zonificacion y Usos de Suelo para el Valle de Guadalupe. Hiptex. https://n9.cl/ti1wc [ Links ]

García, J. (26 de enero de 2023). Provino a favor de cancelar conciertos en el Valle de Guadalupe. El Imparcial. https://bit.ly/3EYW0u7 [ Links ]

García, S. (15 de octubre de 2013). Productores revelan intereses políticos. El Horizonte. http://bitly.ws/9vJR [ Links ]

Garrido, F. J. (2001). El análisis de redes en el desarrollo local. En T. Rodríguez-Villasante Prieto, M. Montañés Serrano, y P. Martín Gutiérrez (Coords.), Prácticas locales de creatividad social. Construyendo ciudadanía/2 (pp. 49-63). El Viejo Topo. https://bit.ly/47xPRB0 [ Links ]

Halperin, S. y Heath, O. (2012). Political research methods and practical skills. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Hanagan, M. y Tilly, C. (2010). Cities, states, trust, and rule: New departures from the work of Charles Tilly. Theory and Society, 39, 245-263. https://bit.ly/3FTDdjX [ Links ]

Hanneman, R. A. y Riddle, M. (2005). Social network data. En R. A. Hanneman y M. Riddle, Introduction to social network methods. University of California. https://bit.ly/2Q6BjTc [ Links ]

Hardin, R. (2001). Conceptions and explanations of trust. En K. S. Cook, Trust in society (pp. 3-39). Russell Sage Foundation. [ Links ]

Heimer, C. (2001). Solving the problem of trust. En K. S. Cook, Trust in society (pp. 40-88). Russell Sage Foundation. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (Inegi). (2018). Conjunto de datos vectoriales de uso del suelo y vegetación escala 1:250000, serie VII. Conjunto Nacional. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. https://www.inegi.org.mx/temas/usosuelo/ [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (Inegi). (2020). Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020. Autor. https://bit.ly/3JeZjjh [ Links ]

Krinsky, J. y Mische, A. (2013). Formations and formalisms: Charles Tilly and the paradox of the actor. The Annual Review, 39, 1-26. https://bit.ly/41vKLSE [ Links ]

Ledeneva, A. (2004). Ambiguity of social networks in post-communist contexts (Working Paper núm. 48). University College London. https://bit.ly/3KIMXiW [ Links ]

Levi, M. y Stoker, L. (2000). Political trust and trustworthiness. Annual Review of Political Science, (3), 475-507. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.475 [ Links ]

Lozares, C. (1996). La teoría de redes sociales. Papers, 48, 103-126. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/papers/v48n0.1814 [ Links ]

Luna González, S. (2003). (8 de agosto de 2003). Cocinan chefs protesta en Baja California. vLex. Información Jurídica Inteligente. https://bit.ly/43MQjdm [ Links ]

Maceiras, I. (13 de noviembre de 2018). Baja California. Una aventura vitivinícola en tierra mexicana. Milenio. https://acortar.link/XMDGdV [ Links ]

Magoni, C. (2009). Historia de la vid y el vino en la península de Baja California. Universidad Iberoamericana. [ Links ]

Marcuse, P. (2010). The forms of power and the forms of cities: Building on Charles Tilly. Theory and Society, 39, 471-485. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-010-9117-1 [ Links ]

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L. y Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. The Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 415-444. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415 [ Links ]

Olvera, F. (2003). Anomalías en el permiso de planta de gas en Valle de Guadalupe. El Mexicano. https://bit.ly/3JtjuKY [ Links ]

Ostrom, E. (2011). Background on the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework. The Policy Studies Journal, 39 (1),7-27. https://bit.ly/3xOzvE9 [ Links ]

Petersen Cortés, G. (2023). Escándalos de corrupción y confianza interpersonal: evidencia de México. Revista Mexicana de Sociología, 85(2), 371-399. [ Links ]

Pierson, P. y Skocpol T. (2008). El institucionalismo histórico en la ciencia política contemporánea. Revista Uruguaya de Ciencia Política, 17(1), 7-38. https://bit.ly/43Bff7G [ Links ]

Putnam, R. D. (1993). What makes democracy work? National Civic Review, 82(2), 101-107. [ Links ]

Quiñónez Ramírez, J., Bringas-Rábago, N. L. y Barrios Prieto, C. (2012). La Ruta del Vino de Baja California. Patrimonio Cultural y Turismo Cuadernos, 18, 131-149. https://bit.ly/41Ee3i5 [ Links ]

Ramírez de la Cruz, E. E. (Ed). (2016). Análisis de redes sociales para el estudio de la gobernanza y las políticas públicas: aportaciones y casos. Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas. [ Links ]

Ramírez de la Cruz, E. E. y Gómez, F. E. (2016). Apartado metodológico, términos y fundamentos básicos del análisis de redes sociales. En E. E. Ramírez de la Cruz (Ed.), Análisis de redes sociales para el estudio de la gobernanza y las políticas públicas: aportaciones y casos (pp. 369-389). Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, V. (22 de septiembre de 2019). Promueven reglamento sustentable para el Valle de Guadalupe. San Diego RED. https://bit.ly/2EbIqae [ Links ]

Santiago, L. (1999). El Valle de Guadalupe: un nuevo destino para el jornalero migrante. Calafia, 9 (3), 53-61. [ Links ]

Secretaría de Desarrollo Social (Sedesol). (2006). Programa de Desarrollo Regional Región del Vino. Comité de Planeación para el Desarrollo Municipal; Centro de Estudios y Planeación del Desarrollo Sustentable de Ensenada. https://bit.ly/40CPGSz [ Links ]

Secretaría de Fomento Agropecuario (Sefoa). (2011). Estudio estadístico sobre producción de uva en Baja California. Sefoa; Gobierno del Estado de B. C.; Oficina Estatal de Información para el Desarrollo Rural Sustentable; Sagarpa. https://bit.ly/3192enK [ Links ]

Seligman, A. B. (1998). Trust and sociability on the limits of confidence and role expectations. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 57(4), 391-404. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1536-7150.1998.tb03372.x [ Links ]

Shaffer, P. (2018). Methodological approaches to the study of Inequality: Applied microeconomics, Kuznets and Tilly (Q-Squared Working Paper núm. 67). https://bit.ly/3MEqnuq [ Links ]

Tarapues Taimal, M. (2012). Las redes clientelistas en los márgenes de estado. El Ágora U.S.B., 12 (2), 403-419. https://doi.org/10.21500/16578031.82 [ Links ]

Tilly, C. (2005). Trust and rule. Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Tilly, C. (2007). Trust networks in transnational migration. Sociological Forum, 22(1), 3-24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1573-7861.2006.00002.x [ Links ]

Uribe, M. (2009). La contienda por las reformas del sistema de salud en Colombia (1990- 2006) [Tesis de doctorado, El Colegio de México]. https://bit.ly/418tvDd [ Links ]

Valenzuela, C. (15 de noviembre de 2013). ¿De qué va el nuevo reglamento y qué implica para los productores y finalmente para los consumidores de vino mexicano? Vinísfera. https://bit.ly/3jiXwzw [ Links ]

Vargas, E. (1 de octubre de 2019). Otorga juez amparo a nativos del Valle contra Reglamento. Ensenada.net. https://bit.ly/3Ls6Egu [ Links ]

Vargas, E. (15 de julio de 2003). Si se realiza la vendimia. Ensenada.net. https://n9.cl/lmuspr [ Links ]

Voicu, M. C. y Babonea, A. M. (2011). Using the snowball method in marketing research on hidden populations. Social Problems, 44(2). [ Links ]

Wasserman, S. y Faust, K. (1995). Social network analysis: Methods and applications. Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Yamagishi, T. y Yamagishi, M. (1994). Trust and commitment in the United States and Japan. Motivation and Emotion, 18(2), 129-166. https://bit.ly/3GQ7alO [ Links ]

6Provino is a civil association that brings together over 80 wineries and has been promoting wine culture in Baja California for over 30 years through various initiatives such as organizing the harvest festival (Fiestas de la Vendimia) and specialized wine tourism experiences. Moreover, it champions the Wine Club with deliveries across Mexico and supports various educational initiatives. More information at https://provinobc.mx/

Received: May 08, 2023; Accepted: June 27, 2023

text in

text in