Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Agricultura, sociedad y desarrollo

Print version ISSN 1870-5472

agric. soc. desarro vol.14 n.4 Texcoco Oct./Dec. 2017

Articles

Socioeconomic and environmental effects of overproduction of maguey mezcalero in the mezcal region of Oaxaca, México

1 División de Ingeniería en Tecnologías Bioalimentarías. Universidad Tecnológica de los Valles Centrales de Oaxaca. Av. Universidad s/n. 71270. San Pablo Huixtepec, Oaxaca. México. (antoniob21@hotmail.com) (marijoseleon95@gmail.com)

2 Departamento de Psicología. Universidad de las Américas Puebla. Ex-Hacienda Santa Catarina Mártir s/n. 72810. San Andrés Cholula, Puebla. México. (alejandra.a28@hotmail.com)

The objective was to analyze the socioeconomic and environmental effects generated by the overproduction of maguey mezcalero (Agave angustifolia Haw) in the Mezcal Region of Oaxaca from the expansion of its cultivation and demand in the production, consumption and global commercialization of tequila. With the approach of multifunctionality of agriculture and transformation of agrarian systems, the maguey agricultural systems were approached as study cases in the communities of Matatlán and El Camarón during the period of 2009 to 2014. A simple random sample of 20 % of the community registries of producing peasants was obtained: surveys and semi-structured surveys were applied to obtain information, in addition to field visits and direct observation; the study was descriptive and analytical. The results indicate that there is a decrease and abandonment of the cultivation of maguey mezcalero because of the lack of demand and the lack of knowledge of peasants about other uses, products and byproducts derived from this raw material, the deterioration of soils due to the absence of traditional agricultural practices, and the decrease in income that worsen the poverty of peasant families in the region.

Key words: indigenous peasants; inulin; agricultural practices; tequila

El objetivo fue analizar los efectos socioeconómicos y ambientales generados por la sobreproducción de maguey mezcalero (Agave angustifolia Haw) en la Región del Mezcal de Oaxaca por la expansión de su siembra y demanda en la producción, consumo y comercialización mundial del tequila. Con el enfoque de la multifuncionalidad de la agricultura y la transformación de los sistemas agrarios se abordaron como estudios de caso los sistemas agrícolas del maguey en las comunidades de Matatlán y El Camarón durante el periodo 2009 al 2014. Se obtuvo una muestra aleatoria simple de 20o% de los padrones comunitarios de campesinos productores: se aplicaron encuestas y entrevistas semiestructuradas para obtener la información, además de recorridos de campos y la observación directa; el estudio fue descriptivo y analítico. Los resultados indican el descenso y abandono de la siembra de maguey mezcalero por la falta de demanda y el desconocimiento de los campesinos sobre otros usos, productos y subproductos derivados de esta materia prima, el deterioro de los suelos por la ausencia de prácticas agrícolas tradicionales y la disminución de ingresos que agudiza la pobreza de las familias campesinas de la región.

Palabras clave: campesinos indígenas; inulina; prácticas agrícolas; tequila

Introduction

Multifunctionality in rural development refers to the relationship between nature and the variety of functions of the territory and rural space (Moyano, 2005; Moyano and Garrido, 2007); with agricultural activity, it is valued for its multiple economic functions and non-economic of dietary and non-dietary production, environmental conservation, equilibrium between ecosystems, preservation of forest spaces, productive maintenance, and socioeconomic articulation of the rural area, raw materials for pharmacology, and agro-energetic crops; without agriculture, it makes possible functions of landscape, nature, leisure, recreation, cultural heritage (Moyano and Garrido, 2007; Moyano, 2008), acquiring an environmental, sociocultural, economic-productive and territorial character (Ayala and Gracia, 2009). Methodologically, it is “the operationalization of the model of sustainable agriculture” (Losch, 2002), as a tool to increase the sustainability of agricultural and non-agricultural activities (Hagedorn, 2005), or as Delgadillo and Torres (2009) indicate, within the analytical frameworks of the territorial approach that processes of local development and rural territorial planning imply. It is determined by externalities or benefits or damages that agriculture causes, but also generates collateral effects that are not incorporated into the production functions, in the costs and incomes from productive activities, nor is it part of the financial analysis of an entrepreneur in particular, but rather they are effects that escape their productive activity, but which affect the social ensemble (Echeverri and Rivero, 2002) and the environmental surroundings where they develop and which determine the functions of agriculture at least in four basic categories: dietary, environmental, social and economic.

The dietary function is related to food security, which implies the physical and economic access to sufficient foods, as pointed out by Antonio et al. (2016), with the healthy and balanced character in the quality of raw materials and of foods elaborated to avoid problems in public health. The environmental function covers the symmetrical relationship between agriculture and the biophysical conditions of the environment to maintain the viability and global health of the ecosystems (Munasinghe, 2009), the rural landscape and the cultural heritage in indigenous communities with the worldview, ideas, thoughts, local knowledge and understandings about the rational exploitation of natural resources in obtaining dietary raw materials of agricultural origin. The economic function refers to the complexity and maturity of the markets (private or not private) in the provision, supply, consumption and commercialization of goods, raw materials and exchangeable foods between productive sectors, generating exportable excess and contributing currency to the economy that drive agriculture and improve the living conditions of the producing peasants under the conservationist rationality, condition that suggests recurrent evaluations to identify and solve the causes of degradation of natural resources; the social function considers the conservation of the generational cultural heritage directed at protecting small-scale family production, traditional rural landscapes, and maintaining employment and income in the rural environment (Valdés and Foster, 2004; Kallas and Gómez, 2004; Gómez et al., 2008).

The conservation practices of the individual, community and regional identity, the language, the organization of coexistence, and of family and community work, and collective self-management should be added to the previous categories, requirements that contribute to the sustainability of agriculture, as it happens in the agricultural systems of maguey mezcalero cultivation in the valleys carried out by Zapotec indigenous people in the Mezcal Region (MR) of Oaxaca (Antonio and Smit, 2012), as a result of their vulnerability to socioeconomic and ecological exogenous factors, particularly those related to the market and to the excessive use of natural resources, such as the case of the expansion of the global tequila market, which have modified it and have originated agricultural restructuring in a double effect: the growth of the agricultural frontier for sowing and the overproduction of maguey mezcalero, causing the socioeconomic decapitalization of indigenous peasants and the environmental deterioration of the region, which is manifested in the decrease and abandonment of their cultivation and soil degradation, accompanied by the cancellation of traditional agricultural practices, situation that has led to food insecurity, changes in the native flora and fauna of biocultural importance, in addition to the unemployment and lack of income that have worsened poverty in the region.

The restructuring of agriculture is part of the transformation processes of the agrarian systems, when connecting to the new rurality in the world. Both make up geo-economic restructuration and geopolitical rearrangement at the global, national and local level, although in each country or locality of the planet it takes on its own peculiarities (Llambi, 1996), associated to structural changes, mutations in public action and rural and regional economic restructuring (Léonard and Losch, 2009) that is expressed in rural persistence (Matijasevic and Ruíz, 2013), multiple ruralities (Llambi, 2010), deruralizatoin and deagrarization (Pérez, 2006; Ruíz and Delgado, 2008; Dirven, 2011), among others, conditions that determine the specific productive territories such as the MR in Oaxaca, which because of its agroclimate characteristics favor the production of maguey mezcalero and mezcal elaboration.

In the new Latin American rurality, socioeconomic phenomena are manifested in social exclusion from the intensification and global expansion of capitalism over the agricultural, livestock and forest sector, the growing diffusion of paid work, the precarization of rural employment, multi-occupation, expulsion of medium-scale producers from the sector, continuous migration from countryside to city or cross-border, orientation of the agricultural and livestock production to markets and the articulation of agrarian producers to agroindustrial complexes, where the decisions from power nuclei linked to large transnational companies predominate (Teubal, 2001), owners of state-of-the-art technologies that contribute to the consolidation of capitalism in the primary sector. Dirven (2011) indicates that the new rurality is also linked to the emergence and development of new activities, to pluriactivity, new social agents, and regulatory entities in the spaces that were previously devoted exclusively to agricultural activities, originating what Kay (2007) refers to as the semi-proletarization of peasants under a new rurality, as observed in the MR where the poverty of indigenous Zapotec peasants is aggravated.

Within this context, the maguey mezcalero productive chain in Matatlán and El Camarón is reconfigured and adapted to the socioeconomic environment when presenting multiple transformations in its productive structure, generating within and outside the productive unit pluriactivity or a group of interdependent economic activities and different from agriculture to integrate a global income and favor its socioeconomic reproduction (Antonio and Ramírez, 2008a). In order of importance, international migration, work as day laborers, and small-scale commerce of merchandise in the communities stand out, constituting local economic flows, survival strategies of the peasant family, and of permanence and development of agriculture through the production of maguey mezcalero (Antonio and Smit, 2012). The diversification of activities complements and restructures the agricultural activity, and is associated to low profitability and productivity, linked to the low incomes obtained that limit the socioeconomic reproduction of peasant families (Antonio 2004; Antonio and Ramírez, 2005; Antonio and Ramírez, 2008a).

At the beginning of the 1980s, tequila producers from Jalisco entered the MR for a short period of time (two years), performing the extraction and purchase of maguey mezcalero at better prices in relation to those established by the mezcal producers. In the year 2000 the purchase intensified; Antonio and Smit (2012) and Antonio et al., (2015) mention that this process generated the restructuring of agriculture through the expansion and increase of maguey cultivation sustained in the remittances from international migration, under an economic rationality at the expense of environmental conservation, using inadequate production techniques and directed at tequila elaboration, but at the time of ending the development cycle and reaching maturity (eight years in average) it became a problem of overproduction due to the lack of demand from the tequila and mezcal producers, and the lack of knowledge of peasants over other uses, products and byproducts, which originated the abandonment and carelessness of sowing, particularly those with a high degree of maturation, also interrupting the performance of traditional agricultural practices such as resowing, among others. This brought with it the suppression of environmental services that the maguey offers, like its contribution to the retention of particles, nutrients and moisture in the soil through its root system, which is characterized by being constituted by small and strong filaments, and anchoring superficially to the ground (Nobel, 1998; Martínez et al., 2005), thus avoiding the soil degradation, in addition to the lack of rotation, association and being interspersed with basic crops such as maize, bean, squash that make it impossible to obtain food security in the communities of study.

The deterioration of soils generated by the causes mentioned is manifested in the compacting, wild growth (favors conservation, but economically is inviable because of the costs for the rehabilitation of the soil for maguey sowing), loss of moisture, and of its physical consistency caused by the expansion of maguey sowing, initially from the change in land use, as highlighted by CONABIO (1998), similar to the Argentine case in 2000, with intensive production of soy, cotton and maize, among others (Pérez et al., 2008). Later, in conditions of overproduction, accompanied by the growth of a biomass made up of low grasses that do not favor the capture of moisture and conservation of fertility, by the loss of wild fauna that participates in biological control, and by the ecological-productive equilibrium through pollination not only of the maguey but also of other plants and native cactuses, whose reproduction is at risk of not taking place.

The objective of the study was to analyze the socioeconomic and environmental effects generated by the overproduction of maguey mezcalero (Agave angustifolia Haw) in the mezcal region of Oaxaca, from the increase in the cultivation and demand in the production, consumption and global commercialization of tequila, which has caused abandonment in the cultivation of maguey mezcalero, deterioration of soils from the absence of traditional agricultural practices, and decrease in income of the peasant families in the region.

Materials and Methods

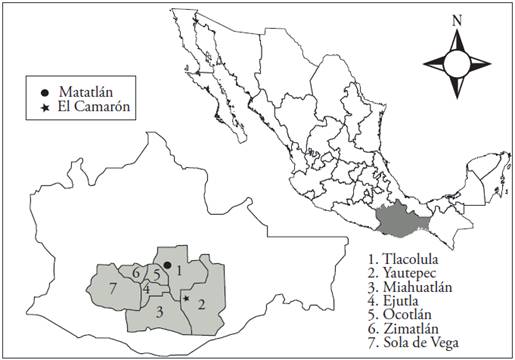

The MR covers the Central Valleys and Sierra Sur of the state of Oaxaca, made up of seven political districts, their municipalities, municipal agencies, and agrarian communities that develop maguey mezcalero agricultural systems in valleys and hillsides (Table 1). For the study, the communities of Matatlán and El Camarón were selected because of their productive importance in maguey.

Table 1 Political districts, municipalities, municipal agencies, agrarian communities, and productive systems of maguey mezcalero in the Mezcal Region of Oaxaca, México.

Source: authors’ elaboration, 2016. * Matatlán is found in Tlacolula ** El Camarón is located in Yautepec.

INEGI (2012) indicates that Matatlán is located at 16° 47’ 3’’ N and 2° 44’ 2’’ E of the meridian in México, at an altitude of 1658 m, with temperate climate, average temperature of 20 °C, 590 mm of rainfall and soils of chromic Luvisol type. In the system of valleys, 70 % of the maguey is sown in association with maize, bean and squash, and the rest as monocrop (Figure 1).

Source: authors’ elaboration, 2016.

Figure 1 Mezcal Region, political districts and maguey and mezcal producing communities in Oaxaca.

El Camarón is located in the northern latitude of 16° 33’ 45’’ and west longitude at 96° 1’ 52’. Its altitude is 690 masl, with dry warm climate, average temperature of 25 °C, and 595 mm of rainfall, Litosol and Regosol soils (INEGI, 2012), agroclimate factors that reduce the period of maturation of maguey. It is characterized because 95 % of the maguey mezcalero is sown on hillsides and in monoculture; the remaining percentage in small valleys associated to maize, primarily (Figure 1).

A community registry was built from both communities with 350 producing peasants with overproduction of maguey mezcalero (N=350). A simple random study sample was obtained of 20 % (n=70); according to Hernández et al. (2010), this is considered reliable for the analysis. It was made up of 45 peasants from Matatlán, from a population of 225, and 25 out of 125 peasants from El Camarón. The study was descriptive and analytical through basic quantitative descriptors; it was carried out from 2009 to 2014, period of overproduction of maguey mezcalero and manifestation of the socioeconomic and environmental effects. The information that refers to overproduction of maguey and deterioration of the soils is obtained from field visits, direct observation, and semi-structured interviews with the peasants with questions related to the origin and causes of the socioeconomic problematic and its effects in the agricultural soil in valleys and hillsides, respectively, highlighting variables about the offer and demand of the raw material, physical state of the soils such as structure, among others. A survey was also applied on the simple random sample calculated in valleys and hillsides, with open and closed socioeconomic and environmental questions referring to the unfavorable effects on the income of peasants and their relationship with the agricultural surface of mature maguey, amount of mature maguey not sold, market and price of the mature maguey, and the physical-productive conditions of the agricultural surface from the abandonment of the crop and traditional agricultural practices; likewise, about other uses of maguey mezcalero under conditions of overproduction.

Results and Discussion

Extraction and purchase of maguey mezcalero for tequila production

In 1980, for the first time, the tequila industrialists carried out the extraction and purchase of maguey mezcalero in the MR (without modifying the NOM 006-SCFI-1994, which points to the use of Agave tequilana Weber maguey), suspending this activity and abandoning the region due to the inconformity of the mezcal producers and the government intervention in the state of Oaxaca (Antonio and Terán, 2008b; Antonio et al., 2015) by disarticulating the mezcal production chain because of the lack of supply and rise in prices of the raw material for its elaboration. The information obtained from the interviews with producer peasants highlights that the extraction and purchase of maguey by tequila producers began in the District of Yautepec at better prices than in the regional market, leaving the raw material out of reach for mezcal producers (Antonio and Ramírez, 2008a; Antonio and Smit, 2012; and Antonio et al., 2015). It coincided with a prolonged drought cycle for rainfed agriculture, causing the decrease in sowing of maguey mezcalero in the region. After the period of interruption of almost twenty years, tequila producers returned to the MR in November 2000 to continue with the purchase of maguey mezcalero (with the modification of the NOM 006-SCFI-1994 to use sugars from other maguey species). Boffil (2004) highlights that they also went into Yucatán to purchase henequen (Agave Fourcroydes) to face the expansion of the global tequila market and, according to Pérez and Echánove (2006), related with the elimination of fees in the international market when favoring exportation, but also with unfavorable effects in other sectors, such as coffee production which in 1989 caused overproduction in México.

In 1999 to 2003, 300 thousand tons of maguey pines came out of the MR in various states of maturity, sown in approximately 10 thousand hectares (Fundación PRODUCE Oaxaca, 2007), surface that increased 35 % since 2000 because of the increase in the price of maguey mezcalero by tequila producers (Antonio, 2004). The information from the surveys applied to the sample of peasants estimates that 70 % of maguey traded came from the district of Yautepec that opted for selling to tequila producers and not to mezcal producers, when reaching prices in the regional market up to four times higher ($4000.00/t) than the one paid by mezcal producers. The prices became a powerful factor to sell to tequila producers because of the conditions of cash payment, in addition to not performing the selection of raw material, as the mezcal producers do, who prefer the maguey with a high degree of maturity (known as maguey “capón”) at a price of no more than $1000.00/t and in deferred payments. The improvement in the prices and conditions of sale fostered maguey sowing in the region; 80 % of the peasant domestic units in Matatlán and El Camarón intensified maguey cultivation in agricultural surfaces of one hectare in average, similar data to those reported by Antonio (2004) and Antonio and Ramírez (2008a). The agricultural surface of maguey mezcalero in the MR estimated through information from the interviews and surveys applied to peasants is more than 15 thousand hectares, surface similar to what is reported by Fundación PRODUCE Oaxaca (2007), which also indicates that the cultivation increased in Zaachila, Etla, the region in the Mixteca, Nochixtlán (San Pedro Teozacoalco and surroundingss), Huajuapan, Silacayoapan, Distrito de Teposcolula, and part of the region of the ravine, communities that do not make up the MR but which because of the demand and better prices opted for sowing maguey mezcalero as an option of agricultural crop.

The indicators from the Maguey Mezcal Product System in Oaxaca (Sistema Producto Maguey Mezcal en Oaxaca, 2004) signal the increase in maguey production, but when comparing it with the information from the surveys applied during this study’s field work, it was observed that the agricultural surface and the population involved in the productive activities are decreasing (Table 2) due to the low profitability of the crop and low incomes, causing the migration of peasants to the USA, as happened with coffee production in México in the early 1990s (Pérez and Echánove, 2006) and with flower production in Colombia during 1996-1999 (Páez, 2008).

Table 2 Basic indicators of the development of maguey mezcalero production in the MR in Oaxaca.

Source: authors’ elaboration, 2016. From the Sistema Producto Maguey Mezcal (2004), (Antonio and Ramírez, 2008b). *Interview with maguey mezcalero producers in study communities. **Information and calculation based on surveys with maguey producers. The mezcal producers call it cut maguey; in the case of Tequilana maguey it is the jima and harvest. S/D: not determined, t: ton, TE: state total.

Official information points toward the development and consolidation of the maguey-mezcal productive chain; however, the situation is adverse for peasants when observing other indicators in Table 2 related to the demand and offer of raw material and the purchasing conditions of mezcal producers: payments in plans longer than six months to peasants who produce maguey, who because of the lack of economic liquidity for maintenance have abandoned the crop, the agricultural farming tasks, and the cutting of mature maguey for its sale.

The agricultural farming tasks abandoned in maguey cultivation that stand out are weeding and manual clearing of the soil, and thinning. The first contribute to improving the capture and use of moisture by maguey and to improve the soil fertility. The second is defining in the growth of the mother plant when separating the shoots (asexual reproduction) that arise three years after establishing the crop; they are cleaned, the roots are cut (to promote the emergence of a new root), and they are selected to establish a new sowing, with these activities requiring the payment of workdays to be done. Under conditions of overproduction, producers do not carry out these activities because of the high costs of workdays, but in order to conserve the sowing they only separate the shoots (without cleaning and selecting) and they dispose of them as a strategy for productive and economic management, and as a savings mechanism when not performing investments for the payment of workdays in the selection and cleaning of shoots. In the case of scarcity and demand, there are two options: 1) Performing weeding, cleaning, selection and using them by the same producer to establish new sowing; and 2) The clean and selected shoots are sold to other producers to establish new sowing at a price during the study period of $5.00 to $12.00 per plant, according to their size and quality.

They did not cut mature maguey because of the high costs that payment of six workdays represented (in total $1200.00), per truck with a capacity of three tons. The cost of the workdays is related to the scarcity of the workforce in the region; in addition to cutting, the payment for transport of the maguey to the palenque for its processing is added (in average $1000.00). Both payments are hardly recoverable due to the null demand during the study period in the region, situation that led to the abandonment of the crop and traditional agricultural practices.

The data from the surveys applied to the sample of producing peasants indicate that under conditions of overproduction of maguey mezcalero, only 5.7 % performed farming tasks, 10 % extracted shoots, 8.4 % did not cut mature maguey, and only 4.3 % carried out the three activities mentioned, associated to auto-production of mezcal. A minority group of peasants who own crops established for two to three years are waiting to obtain information referring to other uses, products and byproducts that can be obtained from maguey mezcalero, such as those mentioned by Antonio (2011), like the production of inulin for the pharmaceutical industry, of biofuels, or sowing associated to oleaginous plants (Ricinus comunis L., Jatropha curcas L.) that makes the establishment of biodiesel producing plants possible. Likewise, Castro (2016) mentions that polylactic acid can be used for the elaboration of packaging for foods, and citric acid for diverse uses.

Agricultural surface and availability of mature maguey

The field visits and the information obtained from the surveys applied to the sample obtained in the communities of study highlight that during the period of overproduction in the cultivation of maguey mezcalero they were in diverse states of maturity; 70 % corresponded to crops with high degree of maturity that required immediate cutting for their processing and reducing to the minimum the economic losses caused by the lack of maguey demand in the region. The information also indicates that when not performing the cutting, the economic losses in the global income of the peasants was 60o%; in this regard, Antonio (2004) reports that under conditions of demand and scarcity the losses represent 30 % of the global income when relating to the frequent variations in the price of the raw material at the price of mezcal in the local and national market, and the presence of intermediaries in the commercialization of the beverage. The rest of the crops (Table 3) begin their stage of maturity and sexual reproduction (with floral scape or quiote); in this case, the producing peasants performed agricultural farming activities focused on the production of plants (flowering, flower pruning, etc.) for the establishment of seedbeds and later new sowing.

Table 3 State of maturity, surface sown, quantity and urgency of the cut under conditions of maguey mezcalero overproduction in Matatlán and El Camarón, Oaxaca, México. 2009-2014.

| Estado de madurez | Superficie sembrada (ha) | Cantidad estimada (t) | Emergencia del “corte” de maguey | ||

| Muy urgente (%) | Urgente (%) | Poco urgente (%) | |||

| Inicio de madurez | 9 | 130 | 9 | 11 | 70 |

| Con quiote | 5 | 72 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Capón | 16 | 283 | 60 | 30 | 10 |

| Muy maduro | 22 | 326 | 75 | 15 | 10 |

| Pudrición | 18 | 212 | 85 | 5 | 5 |

Source: authors’ elaboration, 2016. From information of field work and surveys applied to peasants from Matatlán and El Camarón, Oaxaca.

This information shows the dimensions of the socioeconomic and productive decapitalization related to the overproduction of maguey mezcalero and the reduction of the global income, situation that worsens the poverty of peasants.

Maguey mezcalero market and prices in Matatlán and El Camarón, Oaxaca

The studies by Antonio and Smit (2012) mention that in 2009 the demand for maguey mezcalero for the production of tequila and mezcal decreased and overproduction took place; accompanied by the socioeconomic effects mentioned, the lack of knowledge about other uses, products and byproducts that can be obtained from this raw material deepened. Based on the field visits and data from the surveys applied in the communities studied, only one producing peasant from Matatlán mentioned having basic verbal information about obtaining inulin; all of them ignore the theme of obtaining biofuels and other products mentioned by Castro (2016), situation that worsened the lack of demand and contributed to the decrease and abandonment of the cultivation of maguey mezcalero in the study period.

During the presence of tequila industrialists in Matatlán and El Camarón, 100 % of the peasants cut maguey in different stages of maturity, traded it and transported it to the stockpile centers established in Tlacolula and El Camarón, at a price of $ 4000.00/t. Another modality of purchase was the maguey plots, also in different stages of maturation, by producers from the region hired by the tequila industrialists for this purpose. The information from the surveys and interviews show that each productive unit sold, in average, 0.75 ha-1, with an average yield of 13 and 17 t/ha in the valleys and hillsides, respectively. All of the peasants pointed out that 80 % of the maguey sold to tequila producers was immature (between five and seven years of cultivation) and the remaining percentage was at the beginning of maturity and without “magueys capons”, which is preferred by mezcal producers because of its high content of sugars and better yields to obtain this beverage.

The data from direct observation, interviews and surveys applied to the study sample estimated that in Matatlán and El Camarón, 25 % of the maguey crops are completely useless due to their high decomposition; instead, 75 % of the crops are useful for obtaining alcoholic beverages, although making the cut soon, because there is between 20 and 30 % of maguey with a high degree of maturity and close to natural decomposition. In this regard, the data from the surveys indicate that in the hillside system, 100 % of the producing peasants presented difficulties to sell the maguey; in contrast, in the valleys they managed to commit the sale to mezcal producers under the modality of “purchase by plot” or “maguey chunks” (in Zapotec, ndaa duva), with an extension not larger than a hectare and generally at low prices.

In the “purchase by plot” modality, peasants offer it in the palenques; if the mezcal producer is interested, he selects and buys the plot close to maturity and with a higher amount of “capones” or close to developing the floral scape or quiote. Both parts establish the price (in the study period in average $ 6000.00 ha-1), generally differed into several payments. When taking possession of the “maguey plot”, the mezcal producer cuts the quitoes, with the aim of increasing the amount of “capones” in the short term (one to two years); then, he selects and begins cutting maguey for its processing, obtaining high yields in mezcal production and immediate earnings. This process of productive-economic transference generates considerable savings for the mezcal producer when not investing during the initial stages of the maguey development cycle; also, the decrease of risks from economic losses related to the adverse climate conditions that the crop occasionally faces.

The strategy of maguey purchase by mezcal producers under the conditions described previously contributes to the permanence of the artisanal productive system in Matatlán (global mezcal capital), process where two elements stand out: 1) In the purchase of maguey plots at low prices, the peasant performs the transfer of the crop because he lacks economic resources to carry out the farming activities during the agricultural cycle. The productive possession is accompanied by a program of natural maturation of maguey related to the needs of the mezcal producer; and 2) A temporary form of property of the maguey plot is established by the mezcal producer when acquiring the rights to perform agricultural activities, established in verbal or written agreements with the peasant maguey producer, who is left without means to perform agricultural activities during the period of time agreed. Generally, the mezcal producer has up to two years to carry out the maguey cut and to return the plot to the owner.

The information about producer peasants during the field work highlights that the farming activities in the two initial stages (six years) of maguey sowing represent 80 % of the production costs from the concept of payment for workdays that the mezcal producer does not perform and which he saves, making the opportunity to purchase the maguey plots more attractive because workdays are only paid for cutting quiotes, which is generally carried out by himself.

In the district of Yautepec, sowing maguey on hillsides is in monocrop and substantial in the local economy; mezcal production is marginal. It is considered as a supplier of raw material because it has the agroclimate conditions that favor and reduce the period of growth of maguey mezcalero (in average seven years). In a situation of overproduction the producer resorted to strategies of economic efficiency that allow the continuity of their crop or conserving the productive vocation in the community, using economic and material assets that he owns, such as freight vehicles (trucks with capacity of up to 3.5 t); they performed the cut of mature maguey and transported it to Matatlán to sell it to mezcal producers, generally in minimum payment plans of two months (period when the mezcal producer sells his mezcal production). The price of sale to mezcal producers in 2012 was $1000.00 per truck with the capacity mentioned before, price that was not enough to cover the expense by concept of cutting and transport, and much less the investment made in the whole cultivation cycle; however, in order to counteract the expenses mentioned, in the cut he used the family workforce saving the payment for this concept, and the sale of maguey is done by taking advantage of the transport of a family member to the state’s capital to carry out personal activities or to purchase of goods that can only be acquired there, with this condition being favored by the geographic location of Matatlán which is on the way to the city of Oaxaca. This sales strategy contributes to the continuity of maguey sowing even under situations of absence of demand and low prices.

Physical-productive conditions of soils and overproduction of maguey

The environmental benefits generated by agriculture are necessary in the production functions of the activity itself, in rural development, in biodiversity conservation, in the combat against deforestation, desertification and drought, among others. The inadequate management or loss of these conditions caused by various factors have unfavorable effects in the ecosystems, as is the case of maguey mezcalero overproduction in the MR caused by socioeconomic factors and the productive actions previously mentioned, which have led to the abandonment of maguey sowing and traditional agricultural practices, causing the deterioration of the agricultural soil where the sowing is carried out, such as compacting, desertification and erosion in the long term, processes that complicate solving other problems that humanity faces, such as food security, biodiversity conservation, and which Derpsch (2005) highlights, related to the production of greenhouse gases to establish carbon sinks in the soil, and those described by CDB (2000) and FAO (1997), linked to the conservation of agricultural biodiversity, among others.

Direct observation, interviews and surveys applied to maguey producing peasants in Matatlán and El Camarón contribute information about the negative effects of abandoning the cultivation and agricultural practices on the gradual degradation of the agricultural soil used in the cultivation of maguey mezcalero and other rainfed agricultural crops. The process of soil degradation is also caused by the intensive use of natural resources, as is the case of forestry, livestock production, agriculture in Argentine rural communities (Moscuzza et al., 2003). The results indicate that the abandonment of maguey cultivation began at the beginning of 2009; same as the extraction and sale, it began during this period in the District of Yautepec, by slightly over 70 % of peasant producers, and months later by those in Matatlán. In this last case, the delay was because of the relation with mezcal elaboration, which in part delayed the socioeconomic and environmental effects caused by the lack in its demand.

Concerning the physical-productive state of the soils, the field observation from direct observation, interviews and surveys applied to producers point out that most of the maguey agricultural surface abandoned has wild growth and is in a gradual process of compacting due to the lack of traditional agricultural practices, such as soil clearing and manual weeding of the crop, which favors the functions and the benefits in the prevention of soil erosion.

In the hillside system, it is observed that compacting at different levels is accompanied by landslide and tends toward immediate erosion from the effect of rainfall that drags the soil particles and organic material, provoking the decrease in filtration and the increase in rockiness, situation that is observed in slightly over 60 % of the agricultural surface of the producers in El Camarón, and to a lesser degree, in Matatlán (Table 4).

Table 4 Physical conditions of the soil, percentage of peasant producers and effects of maguey mezcalero overproduction in the MR.

| Condiciones físicas del suelo | Nivel de afectación del suelo* | % de productores | ||

| Matatlán | El Camarón | Matatlán (n=45)** | El Camarón (n=25)** | |

| Compactación | alto | alto | 93.3 | 92.0 |

| Enmontamiento | alto | alto | 86.6 | 80.0 |

| Compactación-Pedregocidad | bajo | alto | 22.2 | 72.0 |

| Desertificación (coloración) | medio | alto | 88.8 | 96.0 |

| Erosión | bajo | medio | 20.0 | 28.0 |

Source: authors’ elaboration, 2016. * It was determined based on the perception of maguey producers related to the physical characteristics of the soil. ** Random sample from each community.

In Matatlán the interview respondents mentioned that, because of the irregularity of the rain period, the desertification of soils is noticeable, and is caused by the loss in its capacity for moisture absorption, which gradually leads to erosion, linked also to the absence of environmental functions that maguey cultivation provides. Likewise, they mention that an indicator of dryness and infertility of the soils is its coloration; in this regard, the information obtained highlights that during the study period slightly over half (Table 4) of the soils have lost their coloration (under sowing conditions they are dark brown), associated to the lack of rains. The crops do not prosper; also, the possibilities of presenting erosion processes in the medium and long term are increased, situation that brings with it difficulties to attain food security and conservation of biodiversity in the communities of study and the MR.

Conclusions

Overproduction of maguey mezcalero in the Mezcal Region of Oaxaca, linked to the expansion of the global tequila market, is product of the restructuring of agriculture through the intensification of maguey mezcalero production under the economic rationality at the expense of environmental conservation, the lack of demand from tequila and mezcal producers, and the lack of awareness of information about the use and extraction of other products and by products derived from this raw material.

Production of maguey mezcalero was interrupted by economic factors related to the market, situation that may cause in the short term the scarcity and speculation of raw material from the high prices that it may reach in the MR, further deepening the disarticulation of the mezcal productive chain.

The abandonment of maguey sowing caused the decrease in the income of indigenous peasants from the lack of demand and offer from tequila and mezcal producers; with the latter, because they depend on the disadvantageous forms of purchase.

Abandoning the cultivation of maguey and the traditional agricultural practices tends to generate compacting, wild growth, desertification and erosion of soils, loss of environmental services that the crop offers in the conservation of soil and agrobiodiversity, which constitutes the basis of food security in the region.

Controlling the problem of maguey mezcalero overproduction requires measures of economic and productive planning of the cultivation, taking into account its demand and offer in the local and national market, control measures of maguey prices, and deterioration of soils, among others, for the protection of the maguey mezcalero productive chain developed by indigenous peasants in the MR.

Literatura Citada

Antonio Juan, Javier Ramírez, y Antonio José. 2016. Agricultura familiar y patrones de consumo alimentario en las familias indígenas de Matatlán, Oaxaca, México. In: Martínez Daniel y Javier Ramírez. (eds). Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación en el Sistema Agroalimentario de México. México. CP, CONACYT, AMC.UPAEP, IMINAP. pp: 393-411. [ Links ]

Antonio Juan, Javier Ramírez, y Mascha Smit. 2015. Origen, auge y crisis de la agroindustria del mezcal en Oaxaca. In: Fernández, Rodolfo, y José Luis Vera. (comp). Agua de las verdes matas. Tequila y Mezcal. México. CONACULTA, ENA, Artes de México y Tequila el Caballito Cerrero. pp: 109-121. [ Links ]

Antonio, Juan, y Mascha Smit. 2012. Sustentabilidad y agricultura en la región del mezcal de Oaxaca. In: Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas. Vol. 3, número 1, Enero- Febrero. [ Links ]

Antonio, Juan. 2011. Viabilidad socioeconómica del agave mezcalero para la producción de biocombustibles, otros productos y subproductos. Informe posdoctoral. CONACYT- CICY. [ Links ]

Antonio, Juan, y Javier Ramírez. 2008a. Agricultura y pluriactividad de los pequeños productores de agave en la Región del Mezcal, Oaxaca, México. In: Agricultura Técnica en México. Vol. 34, número 4, Octubre-Noviembre. [ Links ]

Antonio, Juan, y Edit Terán. 2008b. Estrategias de producción y mercadotecnia del mezcal en Oaxaca. In: El Cotidiano Revista de la realidad mexicana actual. Año 23, número 148, Marzo-Abril. [ Links ]

Antonio, Juan , y Javier Ramírez. 2005. Sostenibilidad y pobreza en las unidades socioeconómicas campesinas de la Región del Mezcal en Oaxaca. In: Wences, R; Sampedro, L; López, R., y J.L. Rosas (comp). Problemática territorial y ambiental en el desarrollo regional. México. 1a. Edición. AMECIDER, UCDR-UAGRO, ININEE- Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo. [ Links ]

Antonio, Juan. 2004. Sostenibilidad y agroindustria del agave en las unidades socioeconómicas campesinas de los valles centrales de Oaxaca. Tesis Doctoral. Programa en Estrategias para el Desarrollo Agrícola Regional. Colegio de Postgraduados-Campus Puebla. México. [ Links ]

Ayala, Dante, y Raúl Gracia. 2009. Contribuciones metodológicas para valorar la multifuncionalidad de la agricultura campesina en la meseta purépecha. In: Economía, Sociedad y Territorio. Vol . IX. No.31, Septiembre-Diciembre. [ Links ]

Boffil, Luis. 2004. Crece producción de tequila, pero la industria está en manos extranjeras. La Jornada, México: Marzo 4, 2004. http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2004/03/04/040n1est.php?printver=1&fly . [Accesado el 12 de mayo de 2016]. [ Links ]

Castro, Agustín. 2016. Crean investigadores de tres centros de ciencia combustible a partir de bagazo de agave. Agencia ID. Periodismo en ciencia, tecnología e innovación en México. Noticiero virtual. 30 de junio de 2016. Disponible en: boletin@nudes.com.mx. [ Links ]

CDB. 2000. Agricultural biological diversity: Review of phase I of the program of work and adoption of a multi-year work program. Quinta reunión ordinaria de la conferencia de las partes en el convenio sobre la diversidad biológica- COPV/5. 15-26 de mayo. Nairobi. Disponible en: >Disponible en: >http://www.cbd.int./decision/cop/?id=7147 . [Accesado el día 12 de marzo de 2016]. [ Links ]

CONABIO. 1998. La diversidad biológica de México. Estudio del país. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad. México. [ Links ]

Delgadillo, Javier, y Felipe Torres. 2009. La gestión territorial como instrumento para el desarrollo rural. In: Estudios Agrarios. Vol . 15. No. 42. [ Links ]

Derpsch, Rolf. 2005. The extent of conservation agriculture adoption worldwide: Implications and impact. Proceedings of the third world. Congress on conservation agriculture: Linking production, lively hoods and conservation Nairobi, Kenya. 3-7 October 2005. Harare African Conservation Tillage Network Productions. http://www.fao.org/ag/ca/doc/IIIWCCA.pdf . [Accesado el 10 de abril de 2016]. [ Links ]

Diario Oficial de la Federación. 1997. Norma Oficial Mexicana del Tequila. NOM 006- SCFI-1994. Bebidas alcohólicas tequila especificaciones. 3 de Septiembre. 1997. México, D.F. [ Links ]

Dirven, Martine. 2011. Corta reseña sobre la necesidad de redefinir rural. In: Dirven, Martine; Rafael Echeverri, Cristina Sabalain, Adrián Rodríguez y Carolina Peña (coord). Hacia una nueva definición de lo rural con fines estadísticos en América Latina. CEPAL. http:/www.eclac.org/publicaciones/xml/3/43523/serie_w-397.pdf . [Accesado el 11 de Enero de 2017]. [ Links ]

Echeverri, Rafael, y María Pilar Rivero. 2002. Nueva Ruralidad: Visión del territorio en América Latina y el Caribe. IICA, CIDER y Corporación Latinoamericana Misión Rural. [ Links ]

FAO. 1997. Informe sobre el estado de los recursos filogenéticos en el mundo. Versión resumida. The estate of the world’s plant genetic resources for food and agriculture. Roma. Disponible en: Disponible en: ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/meeting/016/aj633s.pdf . [Accesado el 18 de febrero de 2016]. [ Links ]

Fundación PRODUCE Oaxaca. 2007. El mezcal. Bebida de los Dioses. In: AGROPRODUCE. Órgano informativo de Fundación Produce Oaxaca. A.C. No. 16. Año. 2. Febrero 2007. Oaxaca, México. [ Links ]

Gómez, José, Tadeo Picazo, y Ernest Reig. 2008. Agricultura, desarrollo rural y sostenibilidad medioambiental. In: CIRIEC-ESPAÑA. Revista de Economía pública, social y cooperativa. No.61. Agosto. [ Links ]

Hagedorn, Konrad. 2005. The role of integrating institutions for multifunctionality. EAAE. Congress. Copenhagen. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.eaae2005.dk/ORGANISED_SESSION_PAPERS/054/737_hagedorn.pdf . [Accesado el 12 de enero de 2017]. [ Links ]

Hernández, Roberto, Carlos Fernández, y Pilar Baptista. 2010. Metodología de la investigación. México: McGraw Hill. 613 p. [ Links ]

INEGI. 2012. Dirección General de Geografía. Coordinación de Desarrollo de Proyectos. Subdirección de Actualización de Marco Geoestadístico. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.inegi.org.mx . [Accesado el 12 de enero de 2017]. [ Links ]

Kallas, Zein, y José Antonio Gómez. 2004. Multifuncionalidad de la agricultura y política agraria: una aplicación al caso de Castilla y León. Universidad de Valladolid, España. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.jcyl.es/web/jcyl/binarios/700/527/Documento_completo%2358.pdf?blobheader=application%2Fpdf%3Bcharset%3DUTF-8&blobnocache=true . [Accesado el 12 de enero de 2016]. [ Links ]

Kay, Cristóbal. 2007. Algunas reflexiones sobre los estudios rurales en América Latina. In: Iconos. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, Núm. 29, Septiembre. [ Links ]

Leónard, Eric, y Bruno Losch. 2009. La inserción de la agricultura mexicana en el mercado norteamericano: cambio estructural, mutaciones de la acción pública y recomposición de la economía rural y regional. In: Foro Internacional. Vol . XLIX. No. 1. [ Links ]

Llambi, Luis. 2010. ¿Hacia una sociología de los procesos territoriales? La transformación de los territorios rurales latinoamericanos a inicios del siglo XXI y los retos de la interdisciplinariedad. In: Memorias VIII Congreso Latinoamericano de Sociología Rural. Porto de Galinhas Brasil. [ Links ]

Llambi, Luis. 1996. Globalización y nueva ruralidad en América Latina: una agenda teórica y de investigación. In: Lara, Sara y Michel Chauvet (comp). La sociedad rural mexicana frente al nuevo milenio. México. Vol .1. UAM-Azcapotzalco, UNAM, INAH. Editorial Plaza y Valdés S.A. de C.V. [ Links ]

Losch, Bruno. 2002. The multifunctionality of agriculture and the challenge for farming in the south: a new foundation for public policies? SFER Meeting the multifunctionality of agricultural activity and its recognition by public policies, 21 y 22 March. Paris. [ Links ]

Martínez, Salvador, Héctor Rubio, y Alfredo Ortega. 2005. Population structure of maguey (Agave Salmiana ssp. Crassispina) in southeast Zacatecas, México. Arid land research and Management. Vol . 19. No. 2. [ Links ]

Matijasevic, María, y Alexander Ruíz. 2013. La construcción social de lo rural. In: revista Latinoamericana de Metodología de la Investigación Social. No.5. Año 3. Abril-Septiembre. [ Links ]

Moyano Eduardo. 2008. Multifuncionalidad, territorio y desarrollo. In: Revista Ambiente. No.81. 2008. [ Links ]

Moyano Eduardo, y Fernando E. Garrido. 2007. La multifuncionalidad agraria y territorial. Discursos y políticas sobre agricultura y desarrollo rural. 2007. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.seer.ufu.br/index.php/revistaeconomiaensaios/article/view/1572/1391 . [Accesado el 12 de enero de 2017]. [ Links ]

Moyano Eduardo . 2005. Nuevas orientaciones de las políticas de desarrollo rural. A propósito del nuevo reglamento FEADER. In: Revista de Fomento Social. Vol .60. No. 238. [ Links ]

Moscuzza, Hernán, Alejo Pérez, Juana Garaicoechea, y Alicia Fernández. 2003. Relación entre las actividades agropecuarias y la escasez de agua en la provincia de Santiago de Estero, Argentina. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.produccion-animal.com.ar/agua_cono_sur_de_america/06-agropecuarias_y_escasez_agua_en_santiago_del_estero.pdf . [Accesado el 14 de enero de 2017]. [ Links ]

Munashinge, Mohan. 2009. Sustainable development in practice. Sustainomics methodology and applications. Cambridge University Press. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.cambridge.org/us/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=9780511537035 . [Accesado el 11 de enero de 2017]. [ Links ]

Nobel, Park. 1998. Environmental biology of agaves and cacti. New York Cambridge University Press. Park Nobel (eds). New York Cambridge University Press.44:1-270. 1998. [ Links ]

Páez, Omaira. 2008. Informe sobre la floricultura colombiana 2008. Condiciones laborales y la crisis del Sector. Corporación Cactus. Bogotá Colombia. [ Links ]

Pérez, Alejo, Hernán Moscuzza, y Alicia Fernández. 2008. Efectos socioeconómicos y ambientales de la expansión agropecuaria. Estudio de caso: Santiago del Estero, Argentina. In: Ecosistemas. Vol .17, No.1. Enero. [ Links ]

Pérez, Edelmira. 2006. Desafíos sociales de las transformaciones del mundo rural: nueva ruralidad y exclusión social. In: Chile Rural. Un desafío para el desarrollo humano. PNUD. Santiago de Chile. [ Links ]

Pérez, Pablo, y Flavia Echánove. 2006. Cadenas globales y café en México. In: Cuadernos Geográficos. No. 38. 2006. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=17103804 . [Accesado el 10 de enero de 2017]. [ Links ]

Ruiz, Naxhelli, y Javier Delgado. 2008. Territorio y nuevas ruralidades: Un recorrido teórico sobre las transformaciones de la relación campo-ciudad. In: Revista EURE. Vol . XXXIV. No.102. Santiago de Chile. [ Links ]

Sistema Producto Maguey Mezcal. 2004. Diagnóstico del sistema producto maguey mezcal. SAGARPA.SEDAF y Consejo Oaxaqueño del Maguey y Mezcal A.C. Oaxaca, México. [ Links ]

Teubal, Miguel. 2001. Globalización y nueva ruralidad en América Latina. In: Norma Giarraca. (comp.) ¿Una nueva ruralidad en América Latina? CLACSO. Asdi. Buenos Aires. [ Links ]

Valdés, Alberto, y William Foster. 2004. Externalidades de la agricultura chilena. Síntesis del estudio ROA para Chile. http://www.rimisp.org.seminariotrm/doc/valdes-y-foster.pdf . [Accesado el 10 de febrero de 2014]. [ Links ]

Received: July 2016; Accepted: January 2017

text in

text in