Phenological studies on the recurring events of organisms, and their relationships to the environment, are basic to understanding ecosystem functioning, communities and population dynamics (Ibarra-Manríquez 1991, Fenner 1998, Sherry et al. 2007, Miller-Rushing & Inouye 2009, Ghyselen et al. 2016).

Most phenological studies focus on species of economic importance (Rathcke & Lacey 1985). In the case of wild flora, phenological studies are restricted to life forms such as trees, shrubs or vines, whereas studies that focus on herbs or epiphytes are scarce (Ibarra-Manríquez 1991, Morellato et al. 2013).

The reproductive phenology of epiphytes, plants that grow on other plants without feeding directly from them, is linked to the presence of pollinators (Ackerman 1986, Zimmerman et al. 1989, Jaramillo & Cavelier 1998, Sheldon & Nadkarni 2015) and to precipitation (Sahagun-Godinez 1996, Sheldon & Nadkarni 2015). Overall, the flowering periods of epiphytes are annual and continuous, lasting for 3-4 months (Sheldon & Nadkarni 2015). For dioecious epiphytes, the two known phenological studies reported an annual flowering pattern of about 8 months that was possibly induced by pollinator behavior, precipitation and solar radiation (Zimmerman et al. 1989, Trejos-Hernández 2015).

Descriptions of the phenology of flowering dioecious plants are necessary to understand the influence of sexual selection on the evolution of sexual dimorphism in plants. It is theorized that reproductive success for male individuals is mainly limited by the number of pollen grains reaching stigmas, whereas female reproductive success is limited by the amount of resources available to invest in seeds and associated structures (Abe 2001, Forero-Montaña & Zimmerman 2010). As a result, it is expected that male individuals should exhibit earlier and longer flowering periods as well as more colorful flowers, compared to female individuals (Forero-Montaña & Zimmerman 2010).

To improve our understanding of the phenology of dioecious epiphytes, we observed the flowering phenology of a population of Catopsis compacta Mez, a monocarpic, dioecious epiphytic bromeliad, in the Northern Sierra of Oaxaca. Owing to the xeric nature of the epiphytic habitat, we expected the flowering period to coincide with the wet season, and the dispersal of anemochorous seeds to occur during the dry season. Also, we expected a high synchrony of flowering in female and male C. compacta individuals because the reproductive success of dioecious species is intimately linked to this synchrony.

Materials and methods

Study site. The study was conducted in an area known as Cerezal (17°15’10” N 96°32’59” W,; elevation 2237 m a.s.l.), in the municipality of Santa Catarina Ixtepeji at the Sierra Norte of Oaxaca, Mexico. The climate varies from temperate to cold humid with summer rains. Annual rainfall varies from 600 to 800 mm (Vidal-Zepeda, 1990) and the average annual temperature is 18 oC (Servicio Meteorológico Nacional, 1971-2000). The vegetation at the study site is classified as oak forest; the trees are mainly Quercus castanea Neé, Q. laurifolia Michx. Q. rugosa Neé, Q. laurina Bonpl., Q. magnoliifolia Neé and Q. laeta Liebm., with some elements of Pinus spp. The epiphytes comprise a large variety of orchids, ferns and bromeliads (Mondragón et al. 2006).

Catopsis compacta Mez (Bromeliaceae), an epiphyte endemic to Mexico, has been recorded in the states of Oaxaca and Jalisco. It is acaulescent and dioecious, with leaves forming a rosette measuring ca. 25-60 cm in length when in flower. The scape is erect; the pistillate inflorescence (9-17 cm long) divides once, with 4-8 spikes each bearing 7-10 flowers; the staminate inflorescence (10-25 cm long) is divides twice, with 10-25 branches, each with 13-21 flowers. The flowers are small (ca. 5-8mm pistillate, ca. 5-7 mm staminate), white and sessile (Utley & Chater 1994, Palací 1997).

To follow the flowering phenology of Catopsis compacta we established a 20 × 20 m plot in February 2006. In this plot we labeled all individuals of C. compacta ≥ 10 cm in height (minimum size observed in reproductive individuals) and measured the length of each one (from the base of the rosette to the tip of the inflorescence). Every month for one year (February 2006 to February 2007) we scored the phenophases of each individual and recorded the numbers of flowers, flower buds and the presence of unopened and opened capsules.

To determine whether plant size and number of flowers differed significantly between female and male individuals, we performed a Student’s t-test (Zar 1984), using Microsoft Excel 365. The proportion of flowering individuals (unimodal or bimodal) was plotted with circular histograms. In addition, we followed SanMartín-Gajardo and Morellato (2003) by considering only phenophase flowering to calculate the following parameters at the individual (i, iv, vi, viii) and population level (ii, iii, v, vii, ix):

I) Duration-number of months that each individual remains in flower.

ii) Mean duration-mean time in months that the species remains in flower: corresponds to the length of each individual phenophase divided by the total number of individuals.

iii) Total duration-the total number of months that the species remains in flower.

iv) Date of first flowering-first month that an individual starts flowering.

v) First date synchrony-standard deviation of the first flowering date of each individual for a given species.

vi) Peak bloom-month maximum for an individual floral display.

vii) Peak date synchrony-standard deviation of the main peak bloom date of each individual. For variables v and vii, high standard deviation values indicate a low synchrony among individuals and zero indicates maximum synchrony.

viii) Index of synchrony of a given individual with its conspecifics (Xi)

Where:

ij = number of months that both individuals i and j were flowering synchronously

f i = number of months that individual i is in bloom

N = number of individuals in the population

When Xi = 1, perfect flowering synchrony occurs, or there is a complete overlap between the flowering periods of individuals i and j in the population; when Xi = 0 flowering does not occur synchronously, or there is no overlap in the flowering periods of those individuals. Intermediate values between 0 and 1 indicate partial flowering synchrony.

ix) Index of population synchrony (Z)-estimates the overlap of flowering periods between individuals of the same species

Where:

Xi= the index of individual synchrony in flowering period

N = the number of individuals in the population

When Z = 1, perfect flowering synchrony occurs, or there is complete overlapping of the flowering periods of individuals i and j in the population; when Z = 0, flowering does not occur synchronously, or there is not overlapping of the flowering periods of those individuals flowering. Intermediate values between 0 and 1 indicate partial flowering synchrony.

We selected SanMartín-Gajardo and Morellato’s (2003) method because their calculation of flowering synchrony is based on Augspurger’s (1983) index, which allows the degree of overlapping at individual and population levels to be estimated. However, Augspurger’s index does not incorporate differences in the intensities of phenological phases, so strictly, this method measures the degree of overlapping, rather than synchronicity per se; nevertheless, it is the most widely used phenological index in phenological studies (Freitas & Bolgrem 2008).

Results

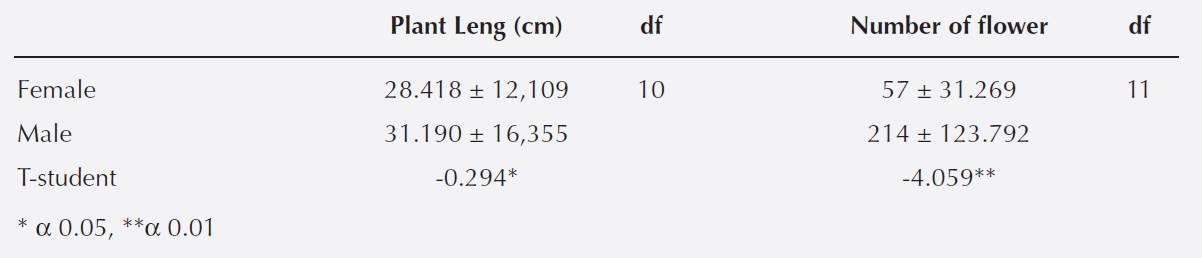

We found 151 adult individuals in our plot, of which only 23 (15.23 %) bore reproductive structures: 12 (52.17 %) were female and 11 (47.83 %) were male. Female and male individuals were similarly sized, but differed in the number of flowers (Table 1); female plants bore fewer flowers compared to male plants.

Table 1 Variation in plant length and number of flowers between female and male individuals of the bromeliad Catopsis compacta at Cerezal, Oaxaca, Mexico (February 2006-January 2007). Includes values of the mean and standard deviation, Student’s t-test, and degrees of freedom.

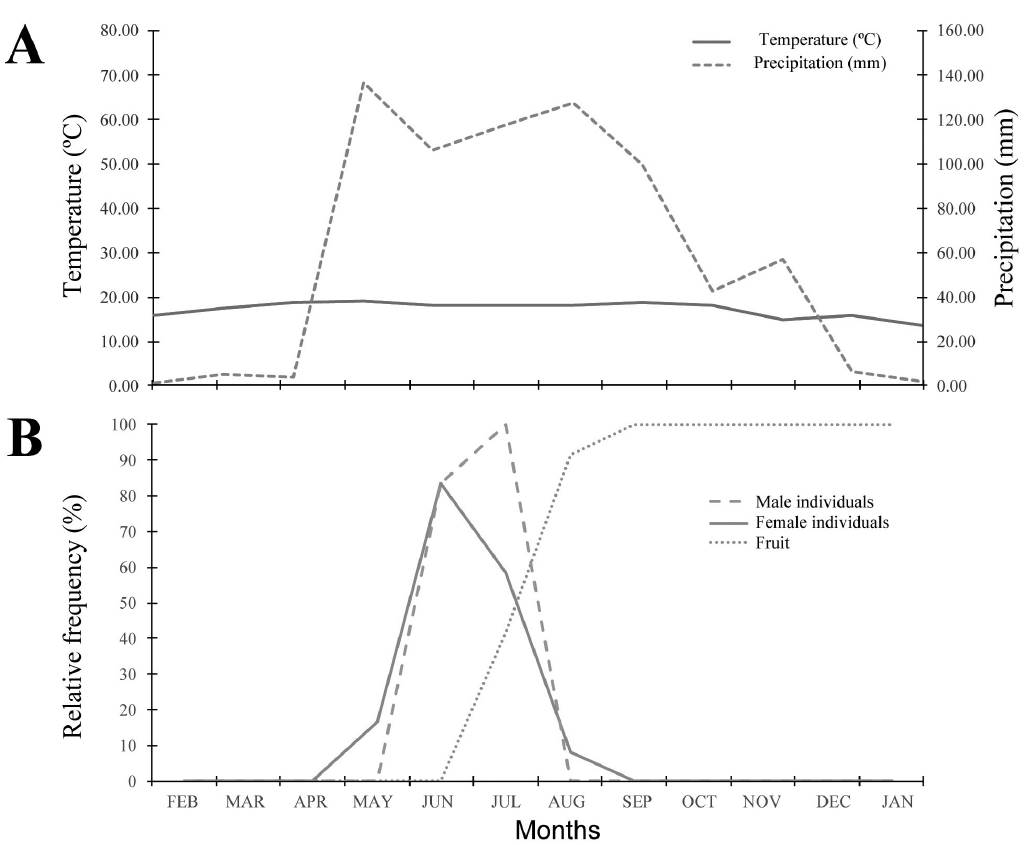

Catopsis compacta displayed a single flowering period (Figure 1) that lasted three months (May, June and July). Fruits began to develop in July and matured in February, whereas seed dispersal began in March and ended in April.

Figure 1 Flowering phenology of Catopsis compacta in Cerezal, Oaxaca, Mexico (February 2006-January 2007). A. Monthly precipitation and temperature data from site. B. Flowering phenology of staminate and pistillate individuals.

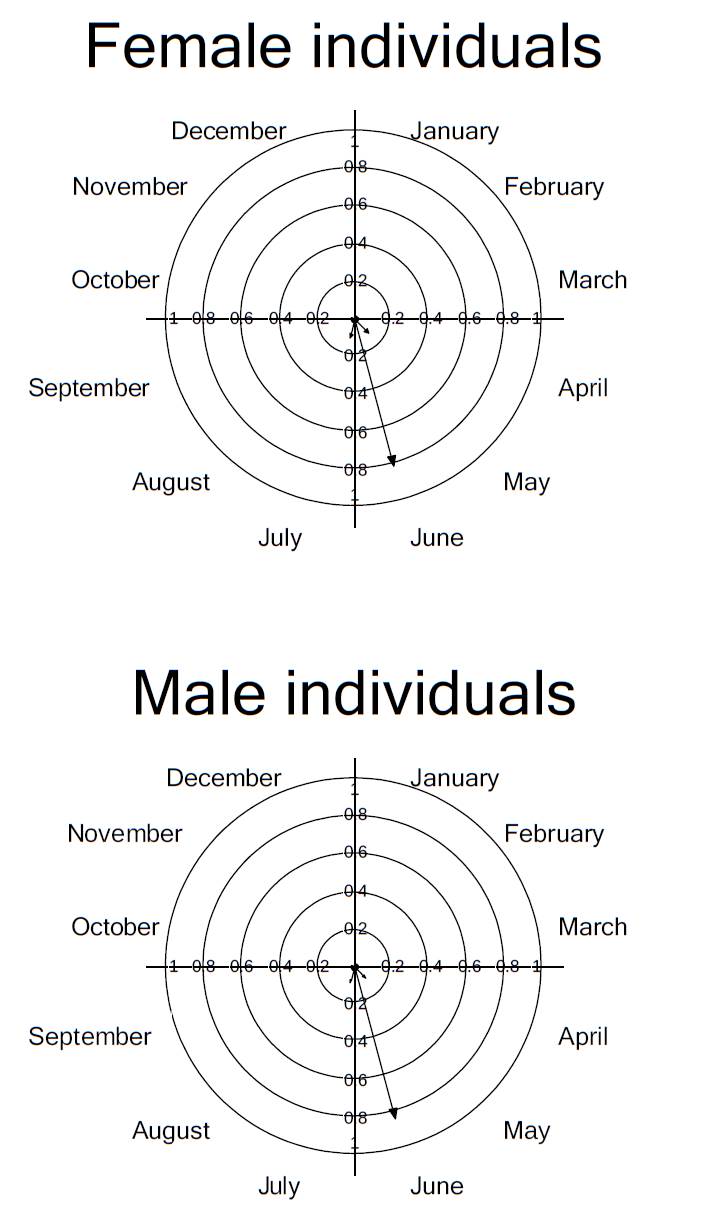

The mean flowering time at the population level was 1.652 ± 0.486 months; for female plants this was 1.416 ± 0.514 months and for males 1.909 ± 0.301 months (Figure 2). At the population level the maximum intensity of flowering occurred in July, with a mean of 3.315 ± 2.056 per day of open flowers; female plants also showed peak intensity of flowering in July (3.714 ± 2.058 open flowers per day), whereas male plants peaked in June (4 ± 1.825 open flowers; Figure 2).

Figure 2 Circular histograms of the flowering pattern of the bromeliad Catopsis compacta at Cerezal, Oaxaca, Mexico (February 2006-January 2007).

The flowering synchrony index for female individuals was 0.723 ± 0.209, and 0.954 ± 0.015 for male individuals. The synchrony index of a male individual with respect to all female individuals was 0.833 ± 0.192; for a female individual with respect to all male individuals the synchrony index was 0.958 ± 0.013. At the population level, the flowering synchrony index was 0.833 ± 0.189.

Discussion

According to the classification by Newstrom et al. (1994), the flowering pattern of Catopsis compacta at the study site is annual, displaying a single flowering stage per year, with an intermediate period of three months (May, June, July). According to Gentry’s (1974) classification, the flowering pattern at population level would be constant for both female and male individuals. These ‘annual’ and ‘constant’ patterns have been reported for members of the Tillandsioideae subfamily (Gentry 1974), to which Catopsis belongs.

Height differences between female and male individuals are considered a product of differential resource allocation to vegetative processes (Espírito-Santo et al. 2003, Barrett & Hough 2012). The lack of size differences between female and male individuals of Catopsis compacta may result from the limited supply of nutrients and water in the epiphytic habitat. Despite the physiological and anatomical adaptations of epiphytes (for example, overlapping leaf bases that form water-storing tanks, peltate trichomes, thick cuticles, etc.), such adaptations may not allow them to store many resources to allocate to vegetative growth. This needs to be investigated furtherdifferences in vegetative features between female and male individuals in a dioecious desert shrub have been documented (Wallace & Rundel 1979). Rather than the scarcity of nutrients or water, the non-differentiation in size could be related to the fact that for epiphytes, an increase in size may increase the chances of death because the supporting substrate may break (Benzing 1990 2000, Mondragón et al. 2015).

With respect to the difference in the number of flowers between female and male individuals, in dioecious species it is common for male plants to produce more flowers per individual than female plants (Bram & Quinn 2000, Espírito-Santo et al. 2003, Munguia-Rosas et al. 2011, Barrett & Hough 2012). Male plants allocate more resources to produce more flowers because their fitness is directly linked to the number of pollen grains released. Further, the bigger the floral display, the more likely it is to be visited by pollinators (Bram & Quinn 2000, Amorim et al. 2011, Forrest 2014).

Female plants have higher resource requirements than male plants because the female bears the costs of production and maintenance of fruits and seeds (Delph 1999, Labouche & Pannell 2016). These costs are energetically expensive, dramatically more so for epiphytes considering the oligotrophic environment in which they grow (Benzing 1990, 2000, Espírito-Santo et al. 2003, Amorim et al. 2011).

Differences in the flowering pattern between female and male individuals, such as those observed in the study population, are common among dioecious plants (Bram & Quinn 2000, Espírito-Santo et al. 2003, Forrest 2014). The early production of staminate flowers (compared to pistillate flowers) has been related to several factors, such as the fact that the reproductive effort of female plants requires a longer period over which resources are accumulated (Forrest 2014), and to the different germination time of seedsmale seeds germinate earlier than female seeds (Barrett & Hough 2012).

Flowering occurred during the rainy season, when annual rainfall can reach up to 120 mm (Vidal-Zepeda 1990). During this period arthropod populations increase (Bhat & Murali 2001, Yamamura et al. 2007) and this could boost the number of possible pollinators of Catopsis compactaa species with an entomophily pollination syndrome. Indeed, we observed wasps, European and native bees visiting C. compacta flowers. Dioecy is strongly related to generalist entomophily (Matallana et al. 2005, Matallana-Tobón 2010).

The fact that the flowering periods of female and male individuals were not perfectly synchronous could be due to the longer flowering period of males and the larger synchrony among them. These factors may increase the chance of pollen being transported to pistillate flowers, and thus, effecting pollination; on the other hand, the lower synchrony and shorter flowering period of females could reduce competition between themif fewer female flowers are displayed simultaneously, it may be more likely that most of them would be visited by pollinators.

The population-level synchrony between female and male individuals of Catopsis compacta (0.833 ± 0.189) can be considered high according to San Martín-Gajardo & Morellato (2003). This was expected, considering that for dioecious populations high flowering synchrony between females and males is necessary to ensure cross pollination (Heilbuth 2000). Also, adequate proximity and abundance of male individuals are essential as these factors have a strong bearing on the availability of pollen, and to some extent, on pollinator behavior (Trejos-Hernández 2015)-as would be the case for this C. compacta population where more than 47 % of the individuals were male.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)