Introduction

The Big Naked-backed Bat, Pteronotus gymnonotus, is a rare and poorly studied species belonging to the Family Mormoopidae. It is one of the 15 currently recognized species of Pteronotus (Pavan and Marroig 2017; Pavan and Tavares 2020). P. gymnonotus is relatively large and heavy, with a forearm length usually measuring 50 to 56 mm. and a body mass between 9.8 to 17.2 gr. The rostrum is conspicuously short and broad. It is mainly characterized by its naked back, resulting from its wing membranes meeting on the dorsal midline. The naked-looking rump is covered with very short fur and appears velvety when examined closely. The overall coloration of the upper parts is dark brown, rarely orange, with generally paler underparts; membranes are blackish brown (Smith 1972; Smith 1977; Pavan and Tavares 2020).

Very little is known about its biology and natural history (Pavan and Tavares 2020). P. gymnonotus is an aerial insectivorous bat that roosts exclusively in caves. Generally, this bat occurs at altitudes below 400 m, inhabiting a variety of habitats from deserts, dry and semi-deciduous forests, to savannas and tropical wet forests (Handley 1966, 1967; Emmons and Feer 1997; Eisenberg and Redford 1999; LaVal and Rodríguez-Herrera 2002; Reid 2009; Pavan and Tavares 2020). In México, it is associated with tropical evergreen high forest (Álvarez-Castañeda and Álvarez 1991a), tropical deciduous forests (Guzmán-Soriano et al. 2013), water bodies and riparian vegetation (Davis et al. 1964; Ibáñez et al. 2000).

It is widely distributed in the Neotropical region, with records from southern México (Veracruz) throughout Central America, and south to Perú, Colombia and Venezuela, northeast and central Brazil, Bolivia, and Guyana (Smith 1972; Simmons 2005; Reid 2009; Pavan and Tavares 2020). Although it can be locally abundant in the southern part of its continental distribution, it becomes less abundant and even rare northwards (Smith 1972; Simmons and Conway 2001; Solari 2019; Pavan and Tavares 2020).

Despite its wide geographical range, this species is relatively poorly represented in scientific collections, with only 618 voucher specimens from Central America (Costa Rica, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama) and 388 from South America (Brazil, Colombia, Peru, Suriname, and Venezuela) collected between 1901and 2016 (GBIF 2020). It is categorized as “subject to special protection” by SEMARNAT in México (NOM-059 SEMARNAT-2010) but overall considered as ‘Least Concern’ according to the IUCN (Solari 2019).

Most of the records for P. gymnonotus in México refer to only single specimens scattered across time. In fact, this species is considered rare not only in México, but also in most of its geographical distribution (Pavan and Tavares 2020). Davis et al. (1964) provided the first record of P. gymnonotus for México based on a single male collected in Cueva Laguna Encantada, Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz. This is its northernmost geographical record, but the species was not recorded again for more than 50 years in spite of subsequent searches made by other authors (Villa-R. 1966; Estrada et al. 1993), including three made by us in March 2005, April 2011 and July 2018. Likewise, Álvarez-Castañeda and Álvarez (1991a)reported one male from Yaxchilan, Chiapas; but its presence in this area could not be confirmed despite the collecting efforts made by Medellín et al. (1986), McCarthy (1987) and Medellín (1993). The species was reported in Tabasco by Ibañez et al. (2000), but prior to that was not found during the intensive field efforts made by Sánchez-Hernández and Romero (1995) and Castro-Luna (1999) in the area, nor later by Castro-Luna et al. (2007). Ibañez et al. (2000) reported the capture of two specimens, a female and a male, from Cueva de Villa Luz, Tapijulapa, Tabasco. Because the female was pregnant, these authors suggested the presence of an undetected reproductive population of P. gymnonotus in southeastern México. Finally, the most recent published record of P. gymnonotus in México is a single male from El Volcán de los Murciélagos, Calakmul, Campeche, captured in November 2010 (Guzmán-Soriano et al. 2013).

The main objectives for this study were: to report the records that demonstrate the presence of this species in southeastern México. To report two new localities in México, one from the state of Tabasco and the first from the state of Oaxaca, and to present data about the natural history of this species in the northernmost extent of its distribution.

Methods and Materials

Study area. We explored caves and some artificial roosts located in Southern México, a region including the states of Campeche, Chiapas, Oaxaca, Quintana Roo, Tabasco, Veracruz, and Yucatan, a low-lying and generally flat region except for the presence of the mountains and hills that make up the Sierra Atravesada, whose highest point “el paso de Chivela” rises to about 250 masl. The area is characterized by a variety of environments with tropical climates which can be humid, sub-humid or semi-dry determined by the presence and amount of rainfall varying from 500 to 4500 mm and with high temperature variation that oscillates between 15 to 34 °C (García 1988; Vidal et al. 2007; INEGI 2008). In general, the rains fall with a marked seasonality, clearly distinguishing a dry season from November to April, and a rainy season from May to October (Cavazos and Hastenrath 1990; Santos-Moreno and Ruiz-Velásquez 2007; Lorenzo et al. 2011). The heterogeneity of the landscape includes seven types of vegetation: the upper evergreen and sub-evergreen forest predominate, followed by medium forest (with two variants, sub-deciduous and sub-evergreen) with small areas of low deciduous forest, savannas, aquatic and underwater vegetations, forest gallery, thorny scrub, and xerophilous scrub (IGGUNAM 2007; INEGI 2008).

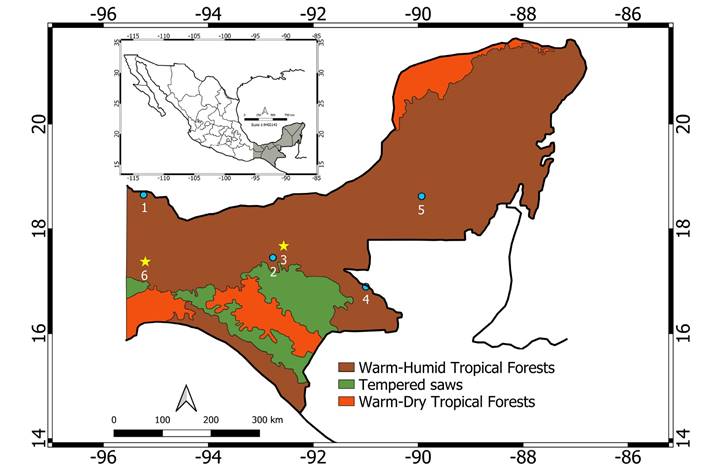

We prioritized sampling of bats inside and near the Tehuantepec Isthmus region, an area located between the -94° and -96° W meridians, which encompasses the states of Chiapas, Oaxaca, Tabasco and Veracruz (Figure 1). It consists of the narrowest land strip that separates the Pacific Ocean from the Gulf of México, spanning only 203 km (North to South), connecting the North American continent with Central America. This area is characterized by warm and humid climates, a rainy season in the summer, an annual average temperature of around 24 to 27 °C, and precipitation ranging from 1,100 to 2,600 mm (García-Romero 2003; Vidal and Matias 2003; Barragan et al. 2010).

Field trips and sampling. Thirteen field trips were undertaken between June 2002 and July 2018 in search of mormoopid bats. Surveys were conducted during both the dry and rainy seasons, with a mean coverage of three to five nights in each locality. We used mist-nets (Avinet Nylon 30 mm mesh) and/or harp-traps (standard 4.2 m2 model). The number of harp-traps and mist-nets varied according the characteristics of each site, but most times we used two of each one. The nets were set before sunset as determined by the expected bat flight routes, or trying to cover cave entrances (Kunz et al. 2009) and remained open for 5 to 7 hours. Every night, we took all captured bats regardless of the species, but when a single species had more of 25 individuals, only a representative portion was collected (approximately 10 to 20 specimens) and the rest were immediately released. Those animals were kept separately in soft cotton bags for a maximum of three hours and released after recording sex, weight, forearm measurements, and obtaining a biopsy from wing membranes using 3.0 mm biopsy punches (Fray Products Corp., Buffalo, NY). Tissue samples were stored at -20o C in 70 % ethanol and deposited in the tissue collection of the Laboratorio de Biología y Ecología de Mamíferos de la Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa (LBEM-UAMI).

Figure 1 Map with all records known to date for Pteronotus gymnonotus in México 1) Cueva Laguna Encantada. 2) Cueva de Villa Luz. 3) Parque Estatal Agua Blanca. 4) Ruinas de Yaxchilan. 5) El Volcán de los murciélagos. 6) Grutas de Martínez de la Torre. Blue dots indicate previously reported localities, yellow stars the new ones described in this work. The depicted ecoregions were obtained from Atlas de Biodiversidad (CCA, CONABIO, INEGI, INE. 2010).

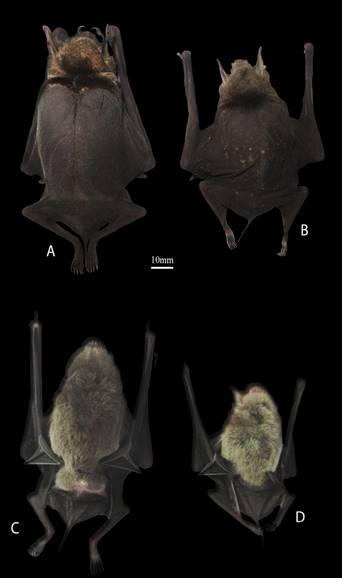

Morphological identifications. Pteronotus gymnonotus is easily distinguishable from other species of Pteronotus by its overall size (forearm length of 50 to 56 mm) and its naked back formed by its fused wing membranes in the dorsal midline, which are diagnostic characters (Medellín et al. 2008; Álvarez-Castañeda et al. 2017). Within its distribution range in México, P. fulvus is the only other bat species that could be confused with P. gymnonotus, but the former is smaller (forearm length between 41 to 49 mm) and much lighter (5 to 10 g; Figure 2).

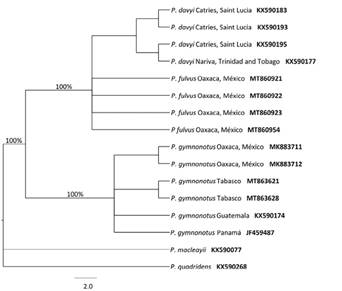

Genetic identification. Species identification was confirmed using molecular techniques. We performed DNA extraction and amplification of a 607 bp fragment of the gene Cytochrome Oxidase Subunit I (COI) following Lopera-Barrero et al. (2008) and using primers VF1d and VR1d, according to Ivanova et al. (2006). The amplifications were sequenced 3’-5 ‘in an ABI PRISM 370xl sequencer. Sequences were edited and aligned in Geneious v. 5.6.4 using the Clustal W algorithm (Kearse et al. 2012) and deposited in GenBank (MK883711, MK883712, MT863621, MT863628). A Bayesian Inference analysis using Mr. Bayes v 3.2 program (Ronquist et al. 2012) was constructed including previously available sequences for P. gymnonotus from Guatemala and Panama, as well as sequences for the phylogenetically closest species P. fulvus and P. davyi. Sequences of P. macleayii and P. quadridens were used as the external group using the optimal evolutionary model estimated with jModeltest v 2.1.6 considering the Akaike information criterion (Posada 2008). In addition, using the program MEGA v. 5.0.5 (Tamura et al. 2011) and the Kimura 2 Parameters (K2P) model, genetic distances between the sequences of individuals of P. gymnonotus, P. fulvus, and P. davyi were estimated.

Figure 2 Dorsal and ventral views of an adult female of Pteronotus gymnonotus (A, C) and an adult female of P. fulvus (B, D). Both specimens were captured in Parque Estatal Agua Blanca, Tabasco, México on December 01, 2014.

Statement of ethics. All bats were collected and handled following the procedures described by the American Society of Mammalogists (Sikes et al. 2016) and our institutional ethical guidelines (Anonymous 2010). Permits to capture and handle the bat species were provided by the Mexican government (SGPA/ DGVS Nos. 05853/13, 09131/14, 003061/18, 9377/19 and CC 08450/92).

Results

During the study period, we visited 44 bat roosts (caves, abandoned buildings and sewers, etc.; Table 1). P. gymnonotus was encountered only in three of the explored caves. We recorded P. gymnonotus in Parque Estatal Agua Blanca, Macuspana, Tabasco (17º 37.20´ N, -92º 28.34´ W, 100 masl; Figure 1). This area has a system of caves measuring 5,200m in length (Castro-Luna et al. 2007). The climate in this area is humid warm, with a mean annual temperature of 26.8 °C, with rains all year round, and average annual precipitation of 2,614 mm (Vargas 2012). We visited this locality in March 2005, April 2011, December 2014, and May 2016. During these visits, we captured a total of three males and twenty-eight females. Tissue samples (biopsy) were taken and stored at the LBEM-UAMI with the following registration numbers: 050305Pgy383, 050305Pgy384, 070411Pg1 to 070411Pg7, 20141201Pgym1 to 20141201Pgym16, 20160508PgyH1 to 20160508PgyH4, and 20160508Pgym1, 20160508Pgym2. The individuals of P. gymnonotus were captured late in the night, most of them between 21:00 to 0:30 hrs. Other bat species captured were Balantiopteryx io, Carollia brevicauda, Lonchorhina aurita, Mormoops megalophylla, Natalus mexicanus, Pteronotus fulvus, P. mexicanus and P. psilotis.

In July 2018, we captured two specimens of P. gymnonotus in Grutas de Martínez de la Torre, Matías Romero Avendaño, Oaxaca (17º 22.26´ N, -95º 11.98´ W; 50 masl; Figure 1). This site is located in northeastern Oaxaca state. It is a cave system surrounded by tropical evergreen forest with warm and humid climate, rainy season in summer and with annual precipitation ranging from <2,000 to 2,500 mm (INEGI 2008). The riparian vegetation is very abundant because a stream emerges from the cave, which joins the Jaltepec River 350 m away. Tissue samples (biopsy) were obtained and deposited in the (LBEM-UAMI), with the registration numbers Pgy23072018m1 and Pgy23072018m2. The bats were two adult males with scrotal testes, and both were collected in a mist net inside the cave at nearly 50 m from the entrance. They were captured late at night (22:00 and 23:30), with more than one hour difference between them. Other bat species captured were Balantiopteryx plicata, M. megalophylla, P. fulvus, P. mexicanus, P. psilotis, and N. mexicanus.

Table 1 Localities sampled in the southeast of México between 2002 and 2018 with their coordinates and arranged in alphabetical order according to the Mexican state, the name of the town and the dates they were visited.

| Localities | Coordinates | Dates (dd,mm,year) |

|---|---|---|

| Campeche | ||

| Grutas de Xtacumbilxunaán, Bolonchén | 19º 59.42´ N, -89º 45.83´ W | 01/03/2005; 30/07/2013 |

| Volcán de los Murciélagos, Calakmul | 18º 31.37´ N, -89º 49.42´ W | 21/02/2005; 19/07/2013 |

| Chiapas | ||

| Cueva de Cerro Hueco, Tuxtla Gutiérrez | 16º 73.33´ N, -93º 08.33´ W | 07/06/2002; 10/05/2013 |

| Cueva de El Aguacero, Ocozocouatla | 16º 04.46´ N, -93º 31.52´ W | 31/03/2014 |

| Cueva de Galicia (El Fresnal), Chicomosuelo | 15º 43.83´ N, -92º 22.71´ W | 11/06/2002 |

| Cueva de Nueva Alianza, Mapastepec | 15º 25.29´ N, -92º 43.98´ W | 07/04/2014 |

| Cueva Lázaro Cárdenas, Tuxtla Gutiérrez | 16º 53.91´ N, -93º 44.44´ W | 10/06/2002 |

| Cueva Los Laguitos, Tuxtla Gutiérrez | 16º 49.32´ N, -93º 09.12´ W | 07/06/2002; 11/11/2007; 11/05/2013 |

| Finca la Esmeralda, Huixtla | 15º 19.14´ N, -92º 30.84´ W | 24/03/2009 |

| Grutas de Arcoton, Ejido Artículo 27 | 16º 16.69´ N, -91º 49.96´ W | 03/04/2014 |

| Grutas de San Francisco, La Trinitaria | 16º 05.89´ N, -92º 02.75´ W | 08/06/2002; 04/04/2014 |

| Grutas de Teopisca, Teopisca | 16º 38.84´ N, -92º 29.63´ W | 02/04/2014 |

| Piedra de Huixtla, Huixtla | 15º 11.90´ N, -92º 28.49´ W | 06/04/2014 |

| Oaxaca | ||

| Alcantarilla, Presa Benito Juárez, Tehuantepec | 18º 15.49´ N, -89º 02.23´ W | 29/07/2007 |

| Cerro Huatulco, Santa María Huatulco | 15º 50.59’N, -96º 21.07´ W | 18/01/2018 |

| Colonia Cuauhtemoc, Matías Romero | 17º 05.04´ N, -94º 52.44´ W | 26/03/2009 |

| Cueva La Mata, Matías Romero | 16º 36.82´ N, -94º 57.14´ W | 23/07/2007 |

| Grutas de Lázaro Cárdenas, Sto. Domingo Petapa | 16º 55.40´ N, -95º 15.21´ W | 10/06/2002; 27/07/2007 |

| Grutas de Martínez de la Torre | 17º 22.26´ N, -95º 11.98´ W | 23/07/2018 |

| Guiengola, Tehuantepec | 16º 19.73´ N, -95º 15.28´ W | 30/07/2007 |

| Ojo de Agua, Tolistoque | 16º 35.19´ N, -94º 52.42´ W | 16/07/2013; 09/04/2014 |

| San Sebastian de las Grutas, Ayoquezco de Aldama | 16º 37.83´ N, -96º 58.40´ W | 28/03/2009 |

| 2km al NW Tapanatepec, Tapanatepec | 16º 22.16´ N, -94º 11.67´ W | 24/07/2007 |

| Quintana roo | ||

| Alcantarilla, Tres Garantías, Othón P. Blanco | 18º 15.49´ N, -89º 02.23´ W | 24/02/2005 |

| Cueva de Kantemó, Dziuché | 19º 55.84´ N, -88º 47.46´ W | 26/02/2005; 21/07/2013 |

| Cueva Ejido Pedro A. de los Santos | 18º 57.55´ N, -88º 12.35´ W | 25/02/2005 |

| Grutas de Aktun Chen, Akumal | 20º 21.64´ N, -87º 20.50´ W | 25/07/2013 |

| Pueblo Chiclero, Chacchoben | 19º 10.49´ N, -88º 15.20´ W | 25/02/2005 |

| Tabasco | ||

| Campus Colegio de Posgraduados, Cárdenas | 17º 57.27´ N, -93º 22.54´ W | 02/03/2005; 19/07/2018 |

| Cueva de Los Vientos, Tapijulapa | 17º 27.50´ N, -92º 46.40´ W | 03/03/2005 |

| Cueva de Villa Luz, Tapijulapa | 17º 27.58´ N, -92º 46.75´ W | 05/06/2002; 05/05/2016; 20/07/2018 |

| Grutas de Coconá, Teapa | 17º 33.52´ N, -92º 56.07´ W | 03/03/2005 |

| Grutas de Cuesta Chica, Tapijulapa | 17º 26.49´ N, -92º 45.54´ W | 04/03/2005 |

| Parque Estatal Agua Blanca, Macuspana | 17º 37.20´ N, -92º 28.34´ W | 05/03/2005; 06/04/2011; 01/12/2014; 08/05/2016 |

| Veracruz | ||

| Cueva Arroyo del Bellaco, Pachuquilla | 19º 13.32´ N, -96º 38.34´ W | 01/06/2002 |

| Cueva Boca del Cántaro, Pachuquilla | 19º 13.78´ N, -96º 38.24´ W | 12/04/2011 |

| Cueva Cerro Colorado, Apazapan | 19º 21.21´ N, -96º 41.77´ W | 15/05/2014 |

| Cueva del Vado de la Chachalaca, Apazapan | 19° 20.25´ N, -96° 39.28´ W | 07/03/2005; 08/12/2014 |

| Cueva Huichapan, Apazapan | 19º 21.35´ N, -96º 41.97´ W | 16/05/2014 |

| Cueva Laguna Encantada, San Andrés Tuxtla | 18º 27.71´ N, -95º 11.18´ W | 07/03/2005; 09/04/2011; 18/07/2018 |

| Cueva Sala Seca, Cuitlahuac | 18°50.00´ N, -96° 93.50´ W | 02/06/2002 |

| Roca del Zopilote, Juchique de Ferrer | 19°47.88´ N, -96° 40.02´ W | 06/06/2014 |

| Yucatan | ||

| Cenote Hoctún, Hoctún | 20º 51.37´ N, -89º 11.70´ W | 27/07/2013 |

| Grutas de Calcehtok, Calcehtok | 20º 33.03´ N, -89º 54.73´ W | 28/02/2005; 28/07/2013 |

The other locality in which we captured P. gymnotus was the Cueva de Villa Luz, Tapijulapa, Tabasco (17º 27.58 ´N, -92º 46.75´ W; 80 masl; Figure 1). This cave is also known as Cueva del Azufre or Cueva de las Sardinas, it includes a main corridor of about 2 km long and more than 20 short side passages formed by the dissolving action of the stream current. The cave has at least 24 skylights, mostly vertical shafts with dissolution features. It has several chambers, some with vaults up to 15m high. However, the passages between the chambers are low. A cave map was published by Hose y Pisarowicz (1999). Its atmosphere contains dangerous concentrations of hydrogen sulfide, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and other harmful gases, in addition to low levels of oxygen; the levels measured exceed the concentrations reported to be toxic for humans. The water, especially that which drips from organic masses known as snottites, is very acidic as well as some springs and streams that are inside the cave. It is a very active ecosystem, based on bacteria that synthesize sulfur and that, contrary to what is expected, allows the existence of a community of several thousand bats (Hose and Pisarowicz 1999; Plath et al. 2006; Guzman-Cornejo et al. 2012; Chambers et al. 2016). Until now, no study has been carried out to understand how bats can fight against the high concentrations of toxic gases and acid fumes present in the atmosphere. The vegetation of the area corresponds to remnants of a high perennial forest, degraded by the clearings for crop and livestock areas. Riparian vegetation is abundant thanks to the large number of streams. Floristic lists of the cave surroundings area are in Gamboa and Ku (1998) and Moreno-Jiménez (2019).

We visited this locality in Jun 2002, May 2016, and June 2018 and during this visits we captured six females and 14 males. Tissue samples were deposited in the LBEM-UAMI with the following registration numbers: 020605PGY1- 020605PGY3; 050516PGY1- 050516PGY10; 200718PGY1- 200718PGY7. Specimens were captured individually between 22:00 and 24:30 hrs. Eight species of bats representing four different families were identified in this cave: two Emballonuridae (B. plicata, Saccopteryx bilineata), five Mormoopidae (M. megalophylla, P. davyi, P. gymnonotus, P. parnellii and P. personatus), and one Vespertilionidae (M. californicus).

In the three localities, the momoopid species P. fulvus was particularly abundant, and although the characteristics of the caves did not allow us to determine the size of their populations, we observed that in each case there were thousands of individuals. In the study area P. gymnonotus and P. fulvus are quite similar to each other (Figure 2), but their differences in size, as well as the forearm values and weight allow their correct separation easily (Table 2). Our genetic analyses also confirmed the identifications made based on morphometric caracteristics, and genetic distances obtained (Table 3), as well as the phylogenetic reconstruction (Figure 3), clearly separate P. fulvus from P. gymnonotus. Due to the rarity of the P. gymnonotus, we highlight the presence of pregnant females in May 2016 in the Cueva de Villa Luz and in the Agua Blanca State Park.

Table 2 Weight and forearm values (mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum) for females and males of Pteronotus gymnonotus and P. fulvus in four locations in the northernmost part of the distribution of P. gymnonotus.

| Pteronotus gymnonotus | Pteronotus fulvus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | D.S. | Min | Max | Mean | D.S. | Min | Max | |

| Cueva de Villa Luz, Tapijulapa, Tabasco | ||||||||

| Females (n = 6)* | Females (n = 14)* | |||||||

| Weight | 15.16 | 0.93 | 14.3 | 17.2 | 8.53 | 0.75 | 7 | 9.5 |

| Forearm | 52.61 | 1.26 | 50 | 53.8 | 44.48 | 0.72 | 43.4 | 46 |

| Males (n = 14) | Males (n = 20) | |||||||

| Weight | 14.02 | 1.25 | 12.2 | 15.9 | 7.46 | 0.59 | 5.8 | 8.7 |

| Forearm | 52.4 | 0.57 | 51.3 | 53.2 | 44.13 | 1.29 | 42.1 | 53.2 |

| Parque Estatal Agua Blanca, Macuspana, Tabasco | ||||||||

| Females (n = 20) | Females (n = 20) | |||||||

| Weight | 13.39 | 1.13 | 9.8 | 14.8 | 7.16 | 0.68 | 6 | 8.1 |

| Forearm | 53.8 | 1.19 | 52.2 | 55.8 | 44.67 | 0.82. | 43.7 | 46.3 |

| Males (n = 5) | Males (n = 20) | |||||||

| Weight | 14.18 | 1.3 | 12.8 | 15.6 | 7.46 | 1.2 | 6 | 10 |

| Forearm | 53.16 | 1.28 | 51.3 | 54.9 | 44.29 | 0.96 | 42.2 | 46.3 |

| Grutas de Martínez de la Torre, Matías Romero Avendaño, Oaxaca | ||||||||

| Females (n = 0) | Females (n = 1) | |||||||

| Weight | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.4 | |||||

| Forearm | 42.6 | 42.6 | 42.6 | |||||

| Males (n = 2) | Males (n = 2) | |||||||

| Weight | 15.3 | 0.07 | 15.3 | 15.4 | 7.55 | 0.35 | 7.3 | 7.8 |

| Forearm | 52.1 | 0.85 | 51.5 | 52.7 | 43.7 | 1.2 | 42.9 | 44.6 |

| El Volcán de los murciélagos, Calakmul, Campeche | ||||||||

| Females (n = 0) | Females (n = 1) | |||||||

| Weight | 6.18 | 0.33 | 5.8 | 6.5 | ||||

| Forearm | 44.5 | 0.6 | 43.2 | 45 | ||||

| Males (n = 1)** | Males (n = 16) | |||||||

| Weight | 14.5 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 6.11 | 0.28 | 5.7 | 6.6 | |

| Forearm | 54.1 | 54.1 | 54.1 | 44.2 | 1.06 | 43.2 | 46,7 |

* = Hembras preñadas.

** Datos obtenidos de Guzmán-Soriano et al. (2013).

Figure 3 Phylogenetic reconstruction of mitochondrial data (COI) to confirm the identification of bats from Martínez de La Torre, Oaxaca (Genbank: MK883711 and MK883712) and Agua Blanca, Tabasco (Genbank: MT863621 and MT863628) as Pteronotus gymnonotus. Sequences of P. gymnonotus from Guatemala and Panama (Genbank: KX590174 and JF459487), P. fulvus from Oaxaca (Genbank: MT860921, MT860922, MT860923 and MT860954) and P. davyi from Saint Lucia and Trinidad and Tobago (Genbank : KX590183, KX590193, KX590197) were included for comparison. Sequences of P. macleayii and P. quadridens (Genbank: KX590077 and KX590268) were used as an external group. Values in branches indicate Bayesian posterior probabilities.

Discussion

The presence of P. gymnonotus in México, the northernmost part of its geographical distribution, was supported only by scattered records in over fifty years (Davis et al. 1964; Álvarez-Castañeda and Álvarez 1991a; Ibañez et al. 2000; Guzmán-Soriano et al. 2013). The three locations reported here, in which we found P. gymnonotus, definitely reaffirm the presence of this species in the country.

Parque Estatal Agua Blanca has been until now the locality with the largest number of specimens collected in México and most of Central America; only Deleva and Chaverri (2018) report a bigger roost for this species in Costa Rica. This locality is a protected natural area of 2,025 ha with tropical evergreen forest as the dominant vegetation type (Castro-Luna et al. 2007; Vargas 2012). According our observations P. gymnonotus seems to prefer to move and forage inside the gallery forest, a vegetation type that is also abundant in the area.

Table 3 Genetic distance data between COI sequences of individuals of P. gymnonotus (Pgy), P. fulvus (Pfu) and P. davyi (Pda). Oaxaca (O), Tabasco (T), Guatemala (G), Antillas Menores (A). Data was obtained using the Kimura 2 Parameters (K2P) model.

| Pgy-O | Pgy-T | Pgy-G | Pfu-O | Pda-A | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pgy-O | - | ||||

| Pgy-T | 1.1 | - | |||

| Pgy-G | 0.7 | 0.3 | - | ||

| Pfu-O | 8.6 | 8.1 | 7.8 | - | |

| Pda-A | 9.0 | 8.6 | 8.2 | 0.05 | - |

Our capture records at Grutas de Martínez de la Torre are important because this cave complex is located near the center of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, 105 km South from the Gulf of México Coast and 134 km North from the Mexican Pacific Coast. This is an area that is well known for being a biogeographic barrier for many taxa (Mulcahy et al. 2006). In it, medium and low deciduous forests predominate, the kind of habitat in which Reid (1999) mentions the presence of P. gymnonotus in South America. The closest previous record corresponds to the Laguna Encantada, Veracruz, located 110 km to the North and we suggest that the Isthmus of Tehuantepec may have played an important role in allowing the expansion of P. gymnonotus northward until reaching the area of Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz. The absence of recent records in this area is probably related to the almost total loss of tall evergreen forests that the region has experienced in recent times (García-Romero et al. 2004; Taubert et al. 2018), and to the intensive use of the cave by the local population for ritual ceremonies (Münch 2012). This location is in the transitional area to the Pacific lowlands, a region in which individuals considerably larger than typical specimens of P. fulvus, and whose measures are very near to those of P. gymnonotus, have been occasionally recorded (Goodwin 1958, 1969; Smith 1972; Álvarez and Álvarez-Castañeda 1991b) suggesting suggesting possible hybridization between those species.

At Cueva de Villa Luz, Gordon and Rosen (1962) reported the presence of at least three large bat colonies, consisting mainly of bats from the Family Mormoopidae. The largest of these colonies is located approximately 150 m from the main entrance, a site with 32.3 °C and a relative humidity of 85 %. In 2018, using a hand net, we captured two specimens of P. gymnonotus among thousands of P. fulvus individuals in this site.

Mormoopid bats are commonly found living syntopically with other members of the same family, as well as with species from other families (Smith 1972; Emmons and Feer 1997). P. gymnonotus, living in the northernmost part of its geographic range, is not the exception. Five families and thirteen species of bats have been recorded associated with this species: three emballonurids (B. io, B. plicata, and S. bilineata), three phyllostomids (C. brevicauda, D. rotundus, and L. aurita), five mormoopids (M. megalophylla, P. fulvus, P. mexicanus, P. personatus, and P. psilotis), one natalid (N. mexicanus) and one vespertilionid (M. californicus; Gordon and Rosen 1962; Palacios Vargas 2009; Guzman-Cornejo et al. 2012; this paper).

In the caves visited by us, we always found P. gymnonotus associated with P. davyi.Pavan and Tavares (2020) observed that P. gymnonotus is rarely found syntopically with other species of naked-backed bats, with only a few sparse records of this situation. However, in the northernmost part of its geographic range, this species usually has been reported to co-occur with P. fulvus (Davis et al. 1964; Ibáñez et al. 2000; this paper).

Our data are indicative of the presence of a reproductive population of P. gymnonotus in the southeast of México. We found pregnant females in May 2016 in the Cueva de Villa Luz and in the Agua Blanca State Park. These females may belong to the same reproductive population, since both places are only 38 km apart. This population seems to be a resident one, because regardless of the year, our samples have covered the months of March to July, plus one in December, and we have always registered the presence of P. gymnonotus in the area.

Beside this, all other P. gymnonotus specimens captured in our field trips were adults, without an evident reproductive status and only one juvenile male was registered in July for Cueva de Villa Luz. This suggests that P. gymnonotus in its northernmost geographic distribution has a monestral reproductive cycle, probably with births between late June - early July, data that are in agreement with the report of pregnant females in the same month in Nicaragua, El Salvador and México (Jones et al. 1971; Hayssen et al. 1993; Ibañez et al. 2000).

Pteronotus gymnonotus is an obligate cave-dweller bat. In Costa Rica colonies have been reported with more than 500 individuals in several karstic caves (Deleva and Chaverri 2018); also large assemblages of many thousands of individuals have been observed in karstic localities in northeastern Brazil (Rocha et al. 2011; Feijó and Rocha 2017; Vargas-Mena et al. 2018). In México, this species is not abundant, with only very few specimens collected in karstic caves in the Parque Estatal Agua Blanca, El Volcán de los Murciélagos and in the Grutas de Martínez de la Torre (Guzmán-Soriano et al. 2013; this paper). It is noteworthy that in México some records are from two non-karstic caves, Laguna Encantada and Villa Luz, both of volcanic origin.

There are studies mentioning that P. gymnonotus is more abundant in dry and semi-open environments (Pavan and Tavares 2020), but in México this species has been recorded in the ecoregion called warm-humid tropical forest located in the low areas along the Gulf of México and in the North and East of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Two earlier reports (Álvarez-Castañeda and Álvarez 1991a; Guzmán-Soriano et al. 2013) recorded this species in moist tropical deciduous forests and we found it associated with large remnants of tropical evergreen forest and especially in gallery forests. Finding P. gymnonotus in this type of environment is probably due to the fact that insectivorous bats often use riparian forests as feeding refuges due to the high availability of insects and the facilities they offer for flight and echolocation (Grindal et al. 1999; Robinson et al. 2002; Hagen and Sabo 2011).

During the last fifty years the processes of deforestation and habitat fragmentation have been very important in southeastern México, the northernmost geographic distribution range for P. gymnonotus. In México, the warm-humid tropical forests include the high and medium evergreen and sub-evergreen forests, which are found almost exclusively in the plains of the Gulf of México, the South and East of the Yucatán Peninsula and the East of Chiapas. It is estimated that these forests have been reduced by more than 80 % in recent years (Challenger and Soberón 2008) at an annual rate of deforestation between 1993 and 2007 of 0.83 %, although this deforestation rate tends to decrease in the area (Kolb and Galicia 2012). Currently these types of forests are only found in the most rugged terrain, but they also continue to be affected by factors such as selective timber extraction, firewood collection, grazing or man-induced fires. Bats have a high tolerance to landscape modification due to their ability to fly and the ease with which they can cross open areas (Medellín et al. 2000; Castro-Luna et al. 2007). In this context, we highlight the need for more precise information about the distribution, conservation status, and ecology of this species.

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)