Introduction

Mammalogy is a discipline that has developed over many years in México. Since the mid-17th century, pioneering foreign researchers dedicated themselves to describing new species of mammals discovered within the borders of México (Baker 1991; Guevara-Chumacero et al. 2001; Ramírez-Pulido et al. 2017). Towards the end of the 19th century, one of the few Mexican researchers who stood out for his contributions to this field was the biologist and naturalist Alfonso L. Herrera, who published works on bats, primates, carnivores and some endemic species of México (Guevara-Chumacero et al. 2001). It was not until the middle of the 20th century that mammalogy began to be notably developed and impacted by Mexican researchers, as Bernardo Villa, founding father of Mammalogy in México, gradually achieving a larger presence and relevance through Mexican universities and institutions (Guevara-Chumacero et al. 2001; Sánchez-Cordero and Medellín 2011; Ramírez-Pulido et al. 2017). In 1984, the Asociación Mexicana de Mastozoología, A. C. (AMMAC), was established to bring together researchers, students and others with an interest in Mexican mammals, allowing improved coordination in the formulation of studies and research programs in mammalogy. The AMMAC has and continue to sponsor conferences where they could provide solutions to the problems, management policies and conservation of these animals and their ecosystems, regarding increasing threats from anthropogenic activities and the effects of climate change (Briones-Salas et al. 2014). These topics require constant research and dissemination.

Unfortunately, there are a few journals in México which focus solely on mammals. Acta Zoológica Mexicana and the Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, although they focus on fauna and biodiversity more generally, they include many articles about mammals. Additionally, the Revista Mexicana de Mastozoología has been published since 1995, with the version “Nueva era” from 2011 onwards (Institute of Biology 2020; Institute of Ecology 2020; INECOL A. C. 2020). This limited number of journals can cause a high demand to publish research and, due to the limited availability of reviewers for the number of articles requested, can generate substantial delays from peer-review to publication (Contreras et al. 2015). In addition to this, there is a certain fear among researchers from developing countries of not being cited in their own country, due either to antipathy, rejection of the national community or the possibility that peers will judge their work in a subjective way, especially when it comes to journals focused on a particular group (Ruiz-Argüelles 1999; Zárate 1999; Cicero-Sabido 2006). For this and other reasons, many researchers choose to publish in journals from other countries with international prestige, thereby avoiding this type of conflict, despite the high cost of publication of many journals. Consequently, the knowledge generated becomes less accessible for researchers and students in México and Latinamerica, in turn making this information less available to the general public.

The constant advancement of different technologies in the area of communication has facilitated the dissemination of information in electronic media, allowing the research generated over the years to reach interested people in almost any part of the world. This, together with the need for a journal specialized in mammalogy, spurred the AMMAC to create and publish the electronic journal Therya, the purpose of which is to freely disseminate research involving mammals from México and Latinamerica (Sosa-Escalante et al. 2014). Such a strategy has a high impact at the national and international level, particularly in recent years, where the number of publications, both articles and scientific notes, in English has increased in order to obtain a broader audience.

A decade has passed since the first issue of Therya was published, and the caliber of research published therein has led to recognition today as one of the mammalogy journals with a high impact factor (1.1; SCOPUS 2019), in addition to being considered a journal of international quality by the National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT; AMMAC 2020). In this manuscript we compiled the Mexican research published in Therya during its first decade, with the aim of analyzing the trajectory of mammalian research in México, including the researchers and institutions that study mammals in Mexican territory, the most studied taxa, topics, methods and geographic scope. Thus, generating a reference baseline to assess gaps of knowledge on less studied aspects of mammalogy during recent years in México. However, future analyses of remaining papers that have been published in Therya from other countries are recomended to estimate the impact of the journal outside Mexican borders.

Material and methods

We searched all the volumes of the journal Therya between the years 2010-2019 (http://www.revistas-conacyt.unam.mx/therya/). We classified publications into articles and scientific notes according to the sections of the journal. Additionally, we considered nine publications as notes between 2010 to 2014 (Gallo-Reynoso and Leo Ortiz 2010; Escobedo-Cabrera and Lorenzo 2011; Gatica-Colima et al. 2011; Jiménez-Maldonado and López-González 2011; Valencia-Herverth and Valencia-Herverth 2012; Verona-Trejo et al. 2012; Hernández-Flores et al. 2013; Martínez-Coronel et al. 2013; Lira-Torres et al. 2014). Altough they were not in the scientific notes section, they have the structure, type of content, length (less than 10 pages), in addition to not being in-depth articles, as considered by Therya as of 2014.

Initially, we made a general description of full-length articles and scientific notes to determine their proportion in México and those in other countries of Latinamerica. From those, we selected those developed only within Mexican territory to analyze existing trends in mammalian research within México. We extracted the following information from each publication and built an Excel® database: historical information (volume, number and year of publication), authors (name, sex [female, male], institution, country of origin), information about the research (title, topic, methods, states of study) and taxa data (order, family, species / subspecies, common name). We generated a database for all species and one for those taxa included in the Mexican endangered species list (SEMARNAT 2019) with their appearance in each year of publication of Therya, and analyzed their trends during 2010 to 2019 and a prediction for the year of 2020 to 2030 with a first-order Jackknife estimator and rarefaction curve, respectively (including species richness S and confidence intervals CI), conducted in the program EstimateS ver. 9.1.0 (Colwell 2013).

The publications, both articles and ascientific notes, were classified into 12 topics, including 11 proposed by Carleton et al. (1993) and reclassified by Guevara-Chumacero et al. (2001): food habits, anatomy and morphology, behavior, conservation, distribution, diseases and parasitism, ecology, miscellaneous (conference, echolocation, histology, body condition, historical review), physiology, reproduction, and taxonomy and phylogeny. To this we added the topic diversity, which included checklists, taxonomic inventories, and diversity analysis.

From the database, we describe the content of Therya in terms of: a) Number of publications, b) Authorship and Institutions, c) State study areas, d) Methods used, e) Taxa studied, and f) Topics studied. We described the results using sample size (n), frequency (%), proportion, mean, and standard deviation (SD). We included the number of full-length articles and notes in each subsection.

Results

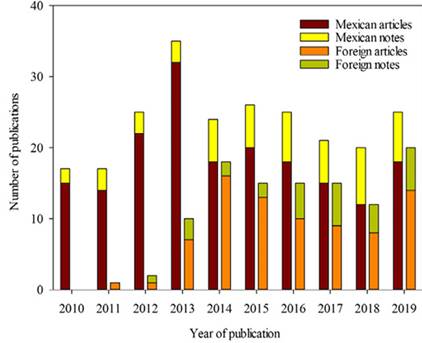

Publications. From its origin until 2019, Therya has published 10 volumes consisting of three issues each; these volumes included 342 publications, of which 261 are articles (76.3 %) and 81 are scientific notes (23.7 %). On average, there were 34.60 ± 10.74 publications per year, with the lowest number of publications (n = 17) in 2010, and the highest (n = 45) in 2013 (Figure 1). During the first three years of publication (2010 - 2012), studies of foreign Latinamerican localities (including articles and notes) were minimally represented in the journal (zero to two publications per year). From 2013 onwards, however, these studies achieved higher frequency, with a mean of 15.71 ± 3.2 publications per year (range, 10 to 20). Of the total publications in Therya, published 181 articles (69.35 %) and 52 scientific notes (64.20 %) reported on studies performed in México, with the the lowest number of articles in 2018 (n = 12) and the highest number (n = 32) in 2013. Only two or three scientific notes were published each year during the first four years of the journal. However, as of 2014, publication of notes increased on average to seven per year, reaching the highest number in 2018 (n = 8). For all subsequents analyses, we focuse solely on the 233 publications pertaining to Mexican localities (http://www.revistas-conacyt.unam.mx/therya/).

Authors and Institutions. These 233 publications were published by 589 authors, with an overall sex ratio of 1:1.58 (female: male); the most equitable participation was in 2010 (1:1.2, n = 55 authors) and the most unequal in 2015 (1:3.23, n = 110 authors). On average, there were 3.89 ± 3.46 SD authors per publication, with a range of 1 to 48 authors. Ninety-four percent of the researchers have participated in a range of one to three publications, ~5 % have between four and nine, while the remaining 1 % are represented by researchers with 10 or more publications: these include Consuelo Lorenzo (n = 16), Juan Pablo Gallo-Reynoso (n = 13), Sonia Gallina-Tessaro (n = 12), Fernando A. Cervantes (n = 11), and Miguel Ángel Briones-Salas and Salvador Mandujano (n = 10 each).

Figure 1 Number of national and foreign publications (articles and scientific notes) in Therya in the period 2010 to 2019.

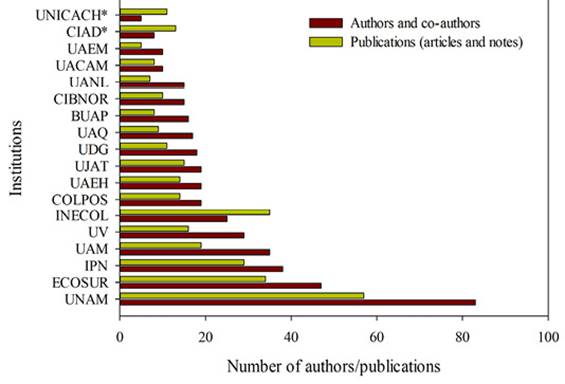

Most of the authors and co-authors (98.13 %) have institutional affiliations (overall, representing 110 institutions), and 27 authors report an affiliation to more than one institution. Eleven authors and co-authors are independent and do not belong to an institution; one of these is a member of an ejido. Sixteen institutions are represented by 10 to 82 authors (or co-authors) each (Figure 2); all other institutions are represented by 1 to 8 authors. In general, the institutions with the highest number of assigned authors also have a greater number of collaborations, with the exception of the Centro de Investigación en Alimentación y Desarrollo A. C. and the Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas, which have fewer than 10 assigned authors but 13 and 11 publications, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Institutions with the highest number of ascribed authors and collaboration in publications in Therya. UNAM - Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, ECOSUR - El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, IPN - Instituto Politécnico Nacional, UAM - Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, UV - Universidad Veracruzana, INECOL - Instituto de Ecología A. C., UJAT - Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco, COLPOS - Colegio de Postgraduados, UAEH - Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo, UDG - Universidad de Guadalajara, UAQ - Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro, BUAP - Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, CIBNOR - Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste, S. C., UANL - Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, UACAM - Universidad Autónoma de Campeche, UAEM - Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, CIAD - Centro de Investigación en Alimentación y Desarrollo, A. C., UNICACH - Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas. An asterisk (*) denotes institutions with less than 10 authors but more than 10 publications.

Education and research institutions make up 62 % of the total institutions that have collaborated in the journal’s publications, followed by non-governamental institutions (27.3 %). Government institutions constitute less than 10 %, with the Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas (CONANP) and the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) collaborating on the greatest number of publications (four each). Only three institutions are private or commercial (Especialidades en Diagnóstico S. A. de C.V., Desarrollos, Proyectos y Gestoría Ambiental S. A. de C. V., and Compañía Minera Cuzcatlán).

Of those publications done in Mexican territory, 22.3 % of the institutions are foreign, from a total of 110 documented institutions. The range of participation of foreign institutions was from one to six publications. The contribution of foreign institutions in order of importance came from New México State University and Texas A&M University, both in the United States. Additionally, other institutions from the United States, United Kingdom, Colombia, Venezuela, Brazil, Canada, Guatemala, New Zealand, Panama, Perú and Sweden have also collaborated in Therya publications.

Mexican institutions represented in Therya publications are distributed across 27 states, mainly México City (n = 16 institutions), Oaxaca (n = 9), Chiapas, Puebla (n = 7 each), and Campeche (n = 6). Only five states are not represented in Therya author institutions; these are Aguascalientes, Colima, Guerrero, Nayarit, and Sinaloa. The most represented institutions at the state level are the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México in five states (Ciudad de México, Estado de México, Michoacán, Morelos, and Veracruz), the Instituto Politécnico Nacional (Ciudad de México, Durango, Oaxaca, and Yucatán) and the Colegio de Posgraduados (Campeche, Estado de México, Puebla, and San Luis Potosí), in four states, respectively. El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (Campeche, Chiapas, and Quintana Roo) and CONANP (Campeche, Chiapas, and Sonora) are represented in three states each.

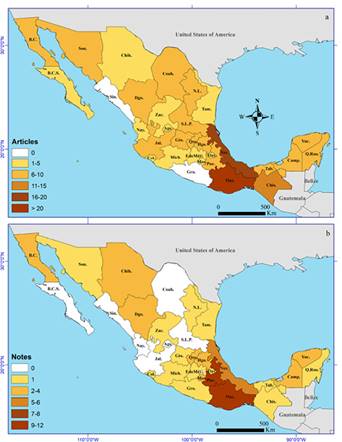

Study areas. Research published in Therya (n = 157 articles, 49 notes) is distributed across 31 of the 32 states of the Mexican Republic (Figure 3). The majority of these publications (85 %) represent work conducted in a single state, with the remainder considering 2 to 11 states as the study area. The most well-represented states within the publications were Oaxaca (16.4 %), Veracruz (7.3 %), Puebla (6.5 %), and Chiapas (5.5 %; Figure 3). The states with the fewest studies include Baja California Sur, Zacatecas, Michoacán, México City and Aguascalientes, each with two to four publications. Nayarit is represented by only one scientific article (Viloria-Gómora and Medrano-González 2015), and Guerrero with a single scientific note (Martínez-Coronel et al. 2013). Sinaloa was not included as a study area in any publication of the journal, article or note, until 2019 (Figure 3). Some publications do not specify a given state in their study area description (n = 27). Of these, five publications were reviews.

Figure 3 Distribution of publications (a) Number of Articles, b) Number of Notes) by Mexican state used as the study area.

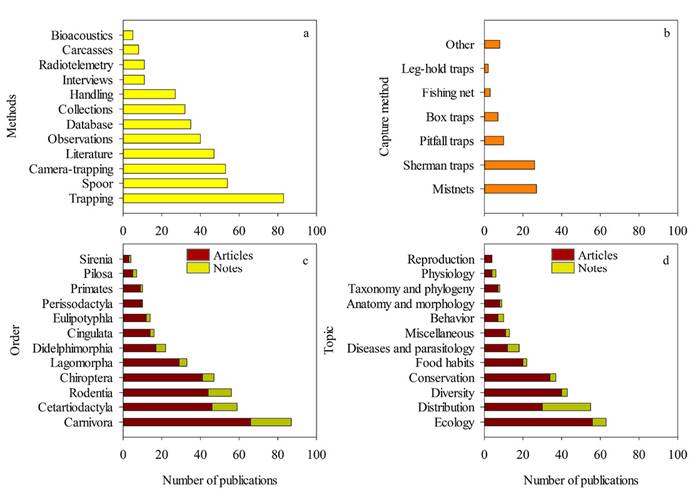

Methods used. Publications in Therya used between one and five methods for the study of mammals each, with the majority (55.5 %) using a single method. Among the least used are the application of forms (e. g., questionnaires, surveys, and interviews) and telemetry, recorded in 11 publications each, as well as the collection and use of corpses (n= 8) and bioacoustics (n = 5; Figure 4 a). The most common methods in the publications are some form of trapping / capture technique, which was included in more than a third of all publications (n = 83), search and use of spoor (n = 54), photo trapping (n = 53), and reviews of literature to obtain data (n = 47; Figure 4 a). Among trapping / capture methods, mist nets and Sherman traps predominate, appearing in 27 and 26 publications, respectively, followed by Pitfall (n = 10 publications) and Tomahawk traps (n = 7 publications); other trapping techniques appear only in three or fewer publications (Figure 4 b). In general, 25 direct sampling methods were used, of which 16 occur during Therya’s first year of publication. In the following years only one or two new methods are added per year, all of them with a low frequency of appearance in the articles (i. e., snares, noose, drop nets, manual net, fishing net, funnel trap, lethal trapping, and snap trapping). Unspecified trapping is presented in three publications.

Taxa studied. Across all publications, 376 species studied come from all orders of mammals known to occur in Mexican territory (Ceballos 2014; Ramírez-Pulido et al. 2014). This includes six domestic / feral species (Bos taurus, B. indicus, Canis lupus familiaris, Felis silvestris catus, Mus musculus, Rattus rattus, and Sus scrofa). In 202 publications (86.8 %), research on species from a single order are addressed, while 27 publications (11.5 %) included two or more orders; four publications (1.7 %) addressed topics on mammals in general (Lorenzo et al. 2012; Briones-Salas et al. 2014; Ramírez-Pulido et al. 2017; Mandujano 2019). The most frequently studied orders in both articles and scientific notes were Carnivora (23.8 %), Cetartiodactyla (16.2 %), Rodentia (15.3 %) and Chiroptera (12.9 %; Figure 4 c), while the least studied orders were Primates (2.7 %), Pilosa (1.9 %) and Sirenia (1 %; Figure 4 c).

Figure 4 Publications in Therya related to: a) methods used for the study of mammals, b) trapping methods most used for the capture of mammals, c) number of articles and scientific notes by order of Mexican mammals, and d) number of articles and scientific notes by topic of study.

Publications on Carnivora and Rodentia span 27 and 26 states of the Mexican Republic, respectively, followed by Cetartiodactyla and Chiroptera in 23 and 20 states, respectively. The publications that include the orders Cingulata, Eulipotyphla, Primates, Pilosa and Sirenia occur in a range between two to nine states of México. The states of Oaxaca, Chiapas, Tabasco and Yucatán are represented in publications that address 10 or 11 orders of mammals (Table 1).

Table 1 Number of publications (articles and scientific notes) by Mexican state used as study area and order of mammal studied. Car = Carnivora; Cet = Cetartiodactyla; Chi = Chiroptera; Did = Didelphimorphia; Eul = Eulipotyphla; Lag = Lagomorpha; Per = Perissodactyla; Pil = Pilose; Pri = Primates; Rod = Rodentia; Sir = Sirenia.

| State | Order | Total orders | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Car | Cet | Chi | Cin | Did | Eul | Lag | Per | Pil | Pri | Rod | Sir | ||

| Aguascalientes | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Baja California | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||||||||

| Baja California Sur | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||

| Campeche | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 5 | |||||||

| Chiapas | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 11 | |

| Chihuahua | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | |||||||

| Ciudad de México | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||

| Coahuila | 2 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 7 | |||||

| Colima | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||||||||

| Durango | 5 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | |||||||

| Estado de México | 1 | 4 | 2 | ||||||||||

| Guerrero | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Guanajuato | 4 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 8 | ||||

| Hidalgo | 7 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 8 | ||||

| Jalisco | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 8 | ||||

| Michoacán | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||

| Morelos | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| Nayarit | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Nuevo León | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||||||||

| Oaxaca | 18 | 17 | 13 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 13 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 11 | |

| Puebla | 10 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 9 | |||

| Querétaro | 5 | 1 | 4 | 3 | |||||||||

| Quintana Roo | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | ||||||||

| San Luis Potosí | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 6 | ||||||

| Sinaloa | 0 | ||||||||||||

| Sonora | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||

| Tabasco | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 10 | ||

| Tamaulipas | 5 | 5 | |||||||||||

| Tlaxcala | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 7 | |||||

| Veracruz | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 8 | ||||

| Yucatán | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 10 | ||

| Zacatecas | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||

| Total states | 27 | 23 | 20 | 9 | 13 | 8 | 15 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 26 | 2 |

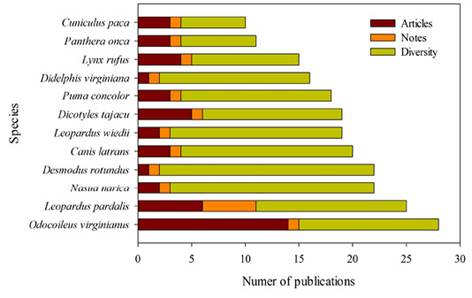

Across all publications, 164 (70.4 %) focused on 83 species individually, while the remaining 69 works (29.6 %) addressed issues related to diversity and abundance of mammals in general or of some particular order, encompassing a total of 365 species. Most single-taxon publications (73.5 %) were scientific articles; the most common taxa studied were the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus; n = 14 articles), the Neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis; n= 13) and the Central American tapir (Tapirella bairdii; n= 10). There are no scientific articles investigating individual species of the orders Cingulata and Pilosa (Appendix 1). Scientific notes addressed 41 species (49.4 % of the total species studied individually), of which the ocelot (Leopardus pardalis; n = 5), the American black bear (Ursus americanus; n = 3), the kit fox (Vulpes macrotis; n = 2), the Cave myotis (Myotis velifer; n = 2) and the Mexican porcupine (Coendou mexicanus; n = 2) were most frequently represented. Pilosa was represented by a single publication (Appendix 1).

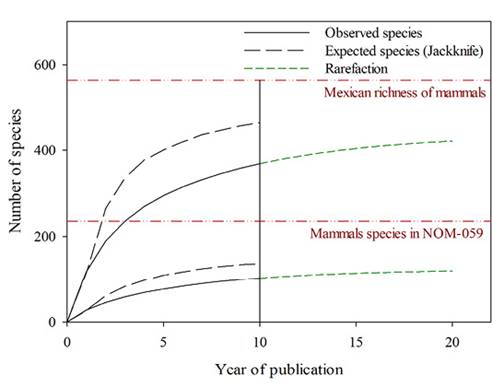

A total of 369 species have been addressed in Therya in its first decade (Figure 5). The expected richness according to the first-order Jackknife estimator is 464 species (± 27 SD), suggesting that Therya has documented only 80 % of the expected species richness. Rarefaction indicates that continued accumulation of new species in Therya will be slow, reaching approximately 434 species (CI 404 - 464) in the following 10 years (Figure 5). Considering the number of species reported for México (S = 564; Sánchez-Corderoet al.2014), the species currently included represent 65 %, and the species estimated for 2030 will be 70.6 % of the richness of mammals for the country (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Number of species mammals represented in both articles and notes published in Therya in its first decade (observed and Jackknife estimated) and predicted by rarefaction over its second decade. Upper lines represent all species in the first decade (S obs = 369, S exp = 464 ± 27) or predicted by 2020 (S = 434, CI = 404-464). Lower lines represent all species in the first decade (S obs = 103, S exp = 136 ± 12) or predicted by 2020 (S = 120, CI = 104-134). Horizontal dashed lines indicate known richness of mammals in Mexico (S = 564) and in NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 (S = 236).

Twenty-one wild species have been reported in both articles and notes (n = 271 publications), generally as part of diversity inventories (66.4 % of the studies). We considered 12 of these species to occur commonly (10 or more occurrences; Figure 6). The majority of species in Therya (S = 271 species) are mentioned only in diversity studies, and most of these (S = 118) belong to the order Chiroptera (Figure 6).

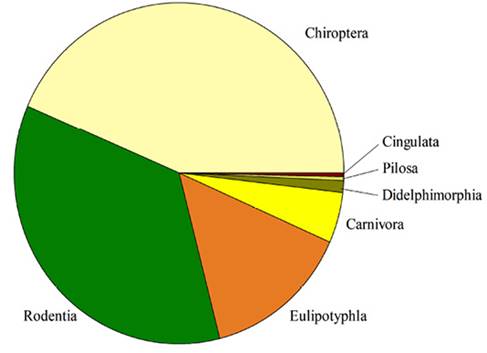

Over one-quarter (27.5 %) of the species in Therya publications (S = 103 species) are listed under some risk category by the Mexican government (e. g., Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-059; SEMARNAT 1994, 2010, 2015); this includes 33 species listed as threatened, 45 species subjected to special protection and 25 species in danger of extinction. Notably, this includes 33 endemic species to México. The species listed in the NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 belong to the orders Carnivora, Chiroptera, Eulipotyphla, Lagomorpha and Rodentia (Figure 7; Appendix 1), and represent 75 % of the species expected in the first 10 years according to the first order Jackknife estimator (136 species ± 12 SD). Rarefaction suggests that a total of 120 species at risk (CI 107 - 134 species) is estimated to be represented in Therya by its 20th year of publication (Figure 5). Species at risk in Therya represent approximately 44 % of species at risk nationally (SEMARNAT 2019; Figure 5), with an expected increase to 51 % in the next 10 years.

Figure 6 Species with the highest number of mentions in the publications of Therya. “Articles” and “Notes” includes all topics exept studies focusing on Diversity; “Diversity” includes both publication types, articles and scientific notes.

Topics studied. Most publications in Therya (77.7 %) focused on only one of the 12 topical categories, followed by 20.6 % that addressed two topics and a minor fraction (1.7 %) that addressed three topics. Among scientific articles, Ecology (24 %), Diversity (17.2 %) and Conservation (14.6 %) stand out, with lesser representation by Anatomy and Morphology, Behavior, Taxonomy, and Phylogeny, Physiology and Reproduction, which together represent 12.9 % of articles. Among scientific notes, the most studied topics were Distribution (45.5 %), Ecology (12.7 %), and Diseases and Parasitism (10.9 %; Figure 4 d, Table 2).

Table 2 Number of publications (articles and scientific notes) with two study topics; the number of posts is indicated under the diagonal. Topics: Food = Food habits; Ana / Mor = Anatomy and Morphology; Beh = Behavior; Cons = Conservation; Dist = Distribution; Div = Diversity; Ecol = Ecology; DisP = Diseases and Parasitism; Phy = Physiology; Rep = Reproduction; Tax = Taxonomy and Phylogeny.

| Topics | Food | Ana / Mor | Beh | Cons | Dist | Div | Ecol | DisP | Phy | Rep | Tax |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ana / Mor | |||||||||||

| Beh | 1 | ||||||||||

| Cons | 3 | ||||||||||

| Dist | 1 | 8 | |||||||||

| Div | 6 | 1 | |||||||||

| Ecol | 3 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 1 | |||||

| DisP | 1 | ||||||||||

| Phy | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Rep | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Tax | 1 | 2 |

Discussion and conclusions

Therya has published for a decade at this point, and is among the principal mammal-oriented publications in México, exceeding in number of publications journals such as Acta Zoológica Mexicana (with 175 publications until 2016), Revista Mexicana de Mastozoología (119 publications), or Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad (101 publications), which have existed over a longer period (since 1955, 1995, and 2005, respectively; Ramírez-Pulido et al. 2017).

The international option of Therya as a journal for publication, particularly as of 2013, influenced a gradual increase in the number of publications with a broader geographical scope, equaling and even exceeding the number of Mexican scientific articles in Therya some years. In addition to this, ~ 14 % of national publications are authored or co-authored by foreign researchers, most of them from institutions in the United States, similar to what was reported by Arizmendi et al. (2015) in Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad. Thus, the historical relationship with educational institutions and journals in that country is maintained through different degrees of collaboration (Ramírez-Pulido et al. 2017). Therya’s process of internationalization allows to establish valuable relationships that strengthen the knowledge of Latinamerican mammals worldwideas it has occurred through the history of the Journal of Mammalogy(Álvarez-Castañeda et al. 2019).

Mammalogy, like the vast majority of disciplines and sciences in México and Worldwide, was historically a male-dominated endeavor (García-Angélica et al. 2012), so authorship by Mexican female researchers was uncommon until recently. As in other areas of science, however, this has changed as gender stigmas have been eliminated, and women have been recognized for their contributions in mammalogy (Lorenzo et al. 2013). Although women have contributed to Therya from its inception, their contributions have increased over the years; a similar trend has been observed in congresses organized by the AMMAC (Lorenzo et al. 2014). In Therya the temporal trend in male authorship has been higher than that for female authors in each year, with a sex ratio range of 1:1.2 to 1:32 (female: male). This reflects similar trends globally, for example, Salerno et al. (2020) noted that in ecological and zoological journals, female authorship has increased only marginally in the last two decades (up to 31 %), and there is a tendency for research groups led by men to publish with fewer coauthors. Although Therya is a relatively young journal, female participation, either as reviewers, editors or authors, includes two women within the group of six researchers with the highest number of publications (Consuelo Lorenzo and Sonia Gallina-Tessaro).

At the institutional level, UNAM has the largest number of authors, co-authors and publications in Therya, similarly to its contribution to other journals such as Journal of Mammalogy (Álvarez-Castañeda et al. 2019). Although in Therya, institutions such as ECOSUR, IPN, UAM and INECOL also have a significant number of publications and attached researchers. These institutions have education and research centers in more than one state of the country; for example, México City includes UNAM, UAM and IPN, older academic institutions that also receive the largest federal or state budget for higher education (DOF 2019). This allows these institutions to maintain a stable staff of researchers, as well as the facilities and equipment necessary to support students and therefore greater visibility in Mexican mammalian research.

At the level of federal entities, México City has been a key center of training for Mexican mammalogists; this indicates a trend of centralization of mammal research in the country (Guevara-Chumacero et al. 2001). Additionally, some of the most important mammalogy collections are housed in the country’s capital (Lorenzo et al. 2012), which greatly facilitates the acquisition of some types of data without requiring field trips, leading to a large number of publications related to this information. Consequently, the institutions that safeguard mammalogy collections (UNAM, UAM and IPN) have sufficient resources to initiate and conduct new studies (Briones-Salas et al. 2014; Arechavala-Vargas and Sánchez-Cervantes 2017). It is clear that state funded institutions of higher education do not publish in the same way as federally funded institutions of higher education, which reflects the budgetary disparity of these entities. This observation suggests that greater support to state funded institutions of higher education might promote research in those sites and areas least explored by mammalogists (Arechavala-Vargas 2011; Arechavala-Vargas and Sánchez-Cervantes 2017; Mendoza-Rojas 2019).

Figure 7 Proportional representation of mammalian orders within NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 (SEMARNAT 2019).

Historically, the states of Veracruz, Sonora, Baja California, Oaxaca, Chiapas, Jalisco and Puebla were the dominant foci of mammalian research in México (Guevara-Chumacero et al. 2001; Briones-Salas et al. 2014; Lorenzo et al. 2014). In Therya, studies in the southern region persist (Oaxaca, Chiapas and Campeche), but the northwest region has been replaced by studies based in the eastern parts of the country (Veracruz, Puebla and Hidalgo). Oaxaca, Chiapas and Veracruz are the states with the highest biodiversity recorded in Mexican territory (SEMARNAT 2012), which makes them attractive for study (Ramírez-Pulido and Castro-Campillo 1993); they also have important institutions for the study and conservation of fauna and its ecosystems (Guevara-Chumacero et al. 2001; Briones-Salas et al. 2014; Lorenzo et al. 2014). Amid the least represented states for field studies are Aguascalientes, Nayarit, Zacatecas and Sinaloa (Guevara-Chumacero et al. 2001; Briones-Salas et al. 2014). In Therya, few or no publications have focused on mammals on those States, and coupled with Baja California Sur, Guerrero, and Michoacán, comprising ~ 5.5 % of the national studies in the journal. The reduced number of studies likely relates to a lack of research groups and social insecurity.

Physical capture was the most widely used approach in the journal’s publications in the last 10 years. Such methods generally are essential for studies on bats and rodents, orders that represent little more than 90 % of the specimens collected and deposited in scientific collections in México (Lorenzo et al. 2012) as well as being the most diverse and abundant groups in the world (Sánchez-Cordero et al. 2014; Mammal Diversity Database 2020). Both orders comprise between 35 % and 43 % of the studies in Therya.

Carnivora and Cetartiodactyla were included in more publications, representing medium to large animals whose study is challenging, both ecologically (e. g., elusive animals; Powell and Proulx 2003; Nielsen et al. 2012; Proulx et al. 2012) and economically (e. g., high cost of trapping and follow-up; Hoffmann et al. 2010; Proulx et al. 2012). For this reason, indirect study methods are more widely represented for these larger taxa, highlighting the search and use of spoor, camera trapping and the literature review, greatly reducing costs and limiting the effort to study these species (Putman 1984; Tomas and Miranda 2003; Guzmán-Lenis and Camargo-Sanabria 2004; Lyra-Jorge et al. 2008; Hoffmann et al. 2010).

The cost associated with the use of mist nets, Sherman traps and camera traps are high and increases with the loss of equipment as well as vandalism and a lack of respect for property by local people (Meek et al. 2019). However, the high representation of these approaches in the journal’s research may reflect an investment aimed at a greater efficiency in data acquisition; additionally, it has become easier to obtain specialized equipment in México that was in the past (Díaz-Pulido and Payán 2012; García-Grajales and Buenrostro-Silva 2019).

It should be noted that the journal’s publications do not include use of new technologies (e. g., drones, environmental DNA; Harper et al. 2019; Leempoel et al. 2020; Schroeder et al. 2020), or some methods that have historically shown their effectiveness for detection of mammals (e. g., use of dogs; Dahlgren et al. 2012; Webster and Beasley 2019). However, the efficiency of these approaches is important for detection of species that traditional methods generally miss (Harper et al. 2019; Leempoel et al. 2020), helping to complete the fauna and diversity studies that are abundant in Therya. The incorporation of new methods in Therya is slow, but their use in conjunction with traditional methods could bring innovation to mammalian studies in México.

We believe that the taxonomic representation of Mexican mammal diversity in Therya is adequate considering it’s only 10 years old. This representation may vary depending on the addition of new species or taxonomic changes (e. g.,Arcangeli et al. 2018; Álvarez-Castañeda et al. 2019; Camargo and Álvarez-Castañeda 2020; León-Tapia et al. 2020). Consecuently, it is of interest to continue with taxonomic descriptions, which can be supported through genetics studies (Guevara et al. 2014). As well as generating updated and complete lists of the species richness of mammals in México. However, the suite of species addressed includes a few that are of particular interest to some researchers, or particularly easy to study, and consequently they attain undue attention in terms of number of publications. The complement to this, however, is that the species that have not been included in Therya or are very poorly represented; as these constitute more than 30 % of the Mexican diversity of mammals (Figure 5), this lack of attention is an important call for action to remedy these taxonomic gaps.

The species given the greatest attention include the white-tailed deer, the Neotropical otter and the Central American tapir, which are also among the most commonly represted at national congresses over the past 20 years (Briones-Salas et al. 2014). Other species that stand out in terms of number of publications (Figure 6) are mostly medium and large mammals with a wide distribution in México (Hall 1981; Ceballos 2014). An increase use of camera traps facilitates the detection and identification of common species of medium and large size, and especially animals that are elusive or that occur at low population densities (O’Connell et al. 2011; Glen et al. 2013; Burton et al. 2015; Nielsen et al. 2012; Proulx et al. 2012). In Therya, the set of species detected occurs generally in inventories, leaving other ecological approaches with records from camera traps unused.

On the other hand, species of the orders Eulipotyphla, Cingulata and Pilosa are the least considered in Therya. Shrews have long been a neglected group, with limited interest by the scientific community in México due to their diminutive nature (e. g., lack of notable “charisma”), and the difficulty of observation, capture and taxonomic identification (Guevara 2019). These animals, along with armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus) and tamandúas (Tamandua mexicana), were most frequently mentioned in faunal lists or diversity analysis, so they are not the main object of research. Even the journal Edentata, published by the Anteater, Sloth, and Armadillo Specialist Group of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), only contains six articles on Mexican taxa between 2010 and 2019 (IUCN SSC anteater, sloth and armadillo specialist group 2020). An increase in publications will require a substantial investment to carry out continuous and long-term studies that allow obtaining unique information. The role of some species as carriers and transmitters of diseases can be taken advantage of for securing funds; for example, the armadillo as an infectious agent of human leprosy (Mycobacterium leprae; Escobar and Amezcua 1981; Truman et al. 2011).

A little-addressed order in Therya is Primates. In this case, there is a trend for authors with research in México to publish in specialized journals, between 2010-2019, 46 such publications accumulated in the American Journal of Primatology (n = 31), Primates (n = 12), and Neotropical Primates (n = 3; American Society of Primatologist 2020; IUCN SSC Primates Specialist Group 2020; Japan Monkey Center 2020). Specialized journals for particular taxa may generate additional interest to publish in them.

Since its first publication in 1994, NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 has been a reference for the conservation status of Mexican species (SEMARNAT 2002). The species under some risk category that are represented in Therya comprise almost 50 % of the species included in the NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 (García-Aguilar et al. 2017), although just over half of these (S = 57 species) were mentioned only in faunal lists or in diversity analyses, thereby contributing to understanding of the range of these species, one of the four criteria considered to be included in the NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 (Tambutti et al. 2001). However, the specific information for the rest of the criteria habitat status, biological vulnerability and impact of human activity (Tambutti et al. 2001) is very limited for all species in general.

The number of species included in NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 generally increased from 204 in 1994, to 236 in 2019, although the 2010 listing stood out for having 245 species listed (SEMARNAT 1994, 2010, 2015, 2019). Fully 44 % of the current species at risk are mentioned in Therya, and this number is expected to increase to 51 % in the next decade. This number will be lower if species additions to NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 decline in the future, or if species are shifted to lower risk categories. Clearly, further work is needed to justify risk categories and to design strategies to reverse conservation threats; these should be considerd as urgent needs in Mexican mammalogy.

The themes addressed in Mexican mammalogy have varied over time. For most of the 20th century, workers emphasized distribution, taxonomy, and phylogeny, followed by parasitism, anatomy, and reproduction (Guevara-Chumacero et al. 2001). These issues assumed lower stature when ecology gained strength in the field of mammalogy after the creation of various institutions focused on it (e. g., INECOL, Secretary of Urban Development and Ecology, National Institute of Ecology). We believe this likely was associated with continued transformation and degradation of habitat due to anthropogenic action, but also to general interest in recovering species and ecosystems (Guevara-Chumacero et al. 2001; Sadlier et al. 2004; Barea-Azeón et al. 2007; Lira-Torres and Briones-Salas 2011; Munguía-Carrara et al. 2019). Studies of physiology and behavior have remained very uncommon in Therya and generally are underrepresented fields of study in Mexican mammalogy (Guevara-Chumacero et al. 2001; Briones-Salas et al. 2014).

Therya has published a number of papers that have expanded knowledge concerning the national mammal fauna over the last decade. Its success in attracting a greater number of publications is also reflected in the fact that an exclusive space for scientific notes Therya Notes (http://mastozoologiamexicana.com/ojs/index.php/theryanotes/) was recently established, allowing Therya journal to focus solely on scientific articles. Likewise, few mammalian orders dominate publications in Therya. We believe that Mexican mammalogists should strive to dedicate attention to the least studied groups and species. Issues such as ecology, diversity, distribution and conservation have flourished in recent years, marking a trend that capitalizes strongly on indirect study methods. The publications in Therya expanding our knowledge of Mexican mammals and highlights some information gaps that require attention in future research. We recommend the integration of innovative themes / topics, diverse methods, as well as the collaborations between institutions. This can maximize both the amount of information obtained, and the impact and utility that they may provide. They can also increase the impact factor of Therya and to build our understanding of Mexican mammals while simultaneously fostering understanding of their conservation and management needs.

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)