INTRODUCTION

The order Chiroptera is considered throughout the world as the second most diverse group of mammals at the species level only after the order Rodentia (Wilson and Reeder 2005). In Neotropical regions, bats are prominent components of mammalian communities and are known to place first with regard to species diversity (Gorresen and Willig 2004; Klingbeil and Willig 2010; Sánchez et al. 2012). Worldwide, more than 1300 extant species have been documented (Voigt and Kingston 2016), with 137 species documented in Mexico (Ramirez-Pulido et al. 2014). A relatively recent study involving the examination of Mexican specimens documented in the scientific collections within the country and abroad reports a diversity of 89 bat species for the state of Veracruz (González-Christen and Delfín-Alfonso 2016). Of these species more than half have been reported for the Los Tuxtlas region (Coates-Estrada and Estrada 1986; Martinez-Gallardo and Sanchez-Cordero 1997; Gonzalez-Christen 2008). Bats are important bioindicators of tropical ecosystem health, as they play a key role in the ecological dynamics of forests, especially in pollination, and promotion of seed dispersal throughout the primary and secondary vegetation. These services extend even to open spaces as well as pastureland (Fenton et al. 1992; Medellín et al. 2000; Castro-Luna et al. 2007; Melo et al. 2009; García-Estrada et al. 2012; Mass et al. 2013; Avila-Cabadilla et al. 2014; Voigt and Kingston 2016). Habitat loss and the resulting forest fragmentation are the major threats to Phyllostomid bats in the tropics. Bats are considered keystone species according to research on the effects of the forest fragmentation. However, fragmentation studies on tropical bats show contradictory results, and should be more widely investigated (Diogo 2015; Farneda et al. 2015; Meyer et al. 2016).

The original predominant vegetation of the lowland area in the Los Tuxtlas region was tall evergreen rainforest. In the last 50 years the forested areas of the region have been drastically altered and reduced due to human perturbation because of the expansion of agricultural activities and extensive cattle ranching practices. Today only between eigth and 10 % of the original forest remains (Dirzo and Garcia 1992; Mendoza et al. 2005; Dirzo et al. 2009; Arroyo et al. 2009), and this presents a highly fragmented scenario consisting of pastureland, cultivations and varying stages of forest regeneration habitat. Studies on the effects of habitat fragmentation in the northwest portion of the Los Tuxtlas region on mammals, birds and plants are well documented (Estrada et al. 1993; Estrada and Coates-Estrada 2001a, Estrada and Coates-Estrada 2002; Galindo and Sosa 2003; Galindo 2004, Aguirre and Dirzo 2008; Arroyo et al. 2012). In the case of bats, studies in other areas have found that forest fragmentation tends to reduce the abundance of certain species and has an overall negative effect on species diversity (Medellín et al. 2000; Farneda et al. 2015; Muylaert et al. 2016).

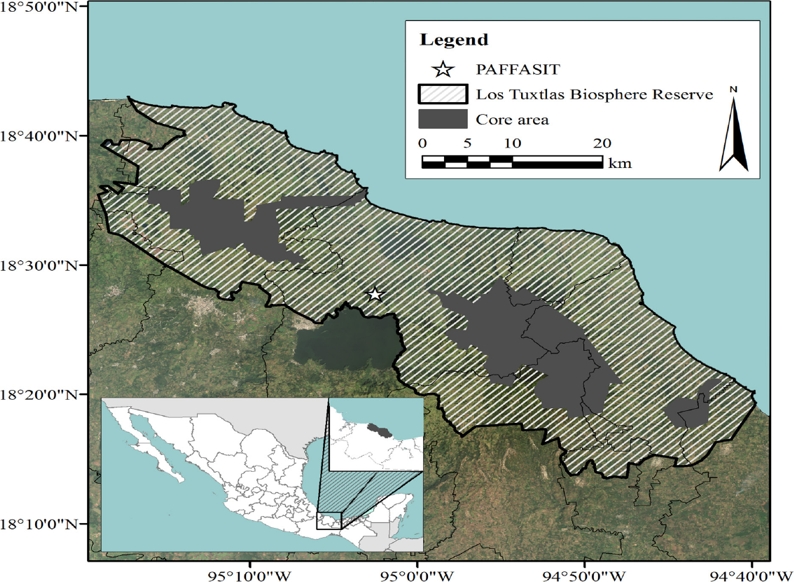

In 1998, an area of 155,200 ha in the Los Tuxtlas region was decreed by the Mexican federal government as a Biosphere Reserve due to its high diversity of organisms and the northernmost location of the tropical rainforest on the American continent. The remaining extensive forest exists in three core areas (San Martín Tuxtla, San Martín Pajapan and Sierra Santa Martha) located at elevations over 800 m. The size of the remaining forest fragments in the lowland areas (0 to 800 m) varies from 1.0 to 700 ha (Estrada et al. 1993; Mendoza et al. 2005).

The aim of this study was to document the species richness, feeding guilds, biomass, and dominance of the understory species assemblage of bats in the Parque de Flora and Fauna Silvestre Tropical (hereafter PAFFASIT). This is a relatively little known area of the Los Tuxtlas region in the lowlands on the northeastern slope of the Sierra Santa Marta volcanic range. Due to the importance of bats in the maintenance of tropical forest natural regeneration and other key ecological processes such as pollination, insect predation, and seed dispersal, it is essential to document the presence of bat species in order to ascertain their roles and ecological impacts in the ecosystem, and to maintain the remaining biodiversity throughout the landscape as pointed out by Lim and Egstrom (2001). We expected that after nearly 30 years of environmental protection, this study site would have maintained its functional diversity, as well as complexity in the bat understory community. Since the relationship between richness and abundance is regulated by area size and the structural complexity of the vegetation, we hypothesize that in the PAFFASIT, a small number of species in the understory will be dominant in terms of abundance and biomass as has been found in other studies conducted on Neotropical bat assemblages.

STUDY SITE AND METHODS

Study site. Fieldwork was carried out in the PAFFASIT a 220 ha forest reserve situated northwest of Lake Catemaco, Veracruz, Mexico 18º 26’ to 18º 28’ N; -95º 01’ to -95º 03’ W, elevation 330 to 500 m (Figure 1). This protected area is owned and operated by the Universidad Veracruzana, which is the state university of Veracruz. The climate is warm and humid with an annual precipitation of 1,663 mm. Annual temperatures range from a minimum of 18.3 ºC to a maximum of 25.1 ºC (Soto and Gama 1997). The vegetation within the reserve is high evergreen rainforest with dominant species such as Ficus yoponensis Desv, Poulsenia armata (Miq.) Standl, and Brosimum alicastrum Sw., mixed with species of medium height such as Guarea glabra Vahl, Garcinia intermedia (Pittier) B. Hammel, and Zanthoxylum kellermanii P. Wilson. However, the endemic bamboo (Olmeca recta Soderstrom), locally known as zongón, dominates certain areas. Many species of pioneer plants (Cecropia obtusifolia Bertol, Piper hispidum SW., and Solanum sp.) are found along the edges of the reserve and in the areas of natural perturbation within the site. Preliminary sampling of bats (Villa-Cañedo 1994) revealed the presence of 16 species.

Figure 1 Map of the Study site location (PAFFASIT) within the Reserva de la Biosfera “Los Tuxtlas” where bats were captured. Latitude and longitude are shown on the vertical and horizontal axes respectively.

We sampled the understory bat community by mist netting throughout the forest and at the edges of the adjoining pastureland of the PAFFASIT reserve monthly from November 2007 to November 2008. A total of 16 mist nets (6 m long x 3 m height; 35 mm mesh) were placed at ground level along existing trails inside the vegetation but under the canopy. Each net was set approximately 50 cm above the ground and the maximum net height reached was 4 m. We netted bats for two consecutive nights, twice each month. Nets were operated from dusk (1,800 to 2,000 hrs) until 0300 hours regardless of lunar phases. All bats caught were identified to species using a field identification key (Medellin et al. 1997, 2008). For each specimen we recorded weight, sex, reproductive state and certain taxonomically useful measurements were taken (total length, tail length, hind foot length, ear length, forearm length). All animals were released as soon as they were processed, and none were marked. Bats that perished due to bad weather, predators or that were unable to be identified in the field were preserved and prepared as voucher specimens and later deposited in the mammal collection of the Instituto de Investigaciones Biológicas of the Universidad Veracruzana in Xalapa, Veracruz. All animals captured were assigned to a feeding guild based on published dietary habits (Kalko et al. 1996, Segura-Trujillo et al. 2016). To determine the ecological impact of bats for this study site we used a measure of biomass (average weight in grams) for each species captured. Taxonomical nomenclature for the bats follows that used by Ramirez-Pulido et al. (2014).

Data analysis. For Species richness estimation, we used Chao 1 with abundance-based data and Chao2, Jackknives, and Bootstrap for incidence-based data (Coldwell 2016). To evaluate species richness, we used the Margalef index (Ludwig and Reynolds 1988). We used the Shannon-Wiener index in order to measure the overall species diversity within the community.

In order to evaluate the sampling effort over time we used a species accumulation curve (Magurran 2004). To calculate the gross biomass (GB) represented by each species we took an average of all recorded weights for the species captured and multiplied this by the total number of captures.

RESULTS

The sampling effort of 1,344 total net/hours in this study captured 509 individuals. Of these, 267 (52 %) were males and 242 (48 %) were females. A total of 22 species (species richness) of bats were identified which represented 16 genera and three families. The most dominant family was that of the Phyllostomidae with a total number of 499 individuals captured (14 genera and 20 species respectively) and represented 98 % of the total captures (Table 1). Four species, Carollia sowellii Baker, Solari and Hoffmann 2002, Sturnira parvidens Goldman 1917, Artibeus jamaicensis Leach 1821 and Glossophaga soricina Pallas 1766, accounted for 79 % of all individuals captured. Sixteen species (70 %) were caught 10 times or less throughout the study.

Table 1 Species richness, and relative abundance of bats captured in PAFFASIT, Municipality of Catemaco, Veracruz from November 2007 to November 2008. Acronyms: IN- Insectivore; FR- Frugivore; N- Nectarivore; S- Sanguinivore. n/d = no data, % B = Contribution of species to total Biomass; % C = Percentage of captures.

| Family | Species | Feeding Guild |

Biomass (g) | Captures | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | by species |

% B | by species |

% C | ||||

| female | male | |||||||

| Mormoopidae | Pteronotus davyi fulvus (Thomas 1892) | IN | n/d | 11 | 11 | 0.11 | 1 | 0.20 |

| Mormoopidae | Pteronotus parnellii mexicanus Smith 1972 | IN | 23 | 24 | 91 | 0.88 | 6 | 1.18 |

| Phyllostomidae | Carollia perspicillata azteca de Saussure 1860 | FR | 18 | 20 | 209 | 2.01 | 11 | 2.16 |

| Phyllostomidae | Carollia sowelli Baker, Solari, and Hoffman 2002 | FR | 19 | 18 | 1,885 | 18.14 | 106 | 20.83 |

| Phyllostomidae | Desmodus rotundus murinus J. A. Wagner 1840 | S | 39 | 37 | 114 | 1.10 | 3 | 0.59 |

| Phyllostomidae | Hylonycteris underwoodi underwoodi Thomas 1903 | N | n/d | 8 | 16 | 0.15 | 2 | 0.39 |

| Phyllostomidae | Glossophaga soricina handleyi Webster and Jones 1980 | N | 11 | 10 | 338 | 3.25 | 32 | 6.29 |

| Phyllostomidae | Mimon cozumelae Goldman 1914 | IN | n/d | 8 | 16 | 0.15 | 1 | 0.20 |

| Phyllostomidae | Artibeus jamaicensis yucatanicus J. A. Allen 1904 | FR | 51 | 47 | 2,051 | 19.74 | 42 | 8.25 |

| Phyllostomidae | Artibeus lituratus palmarum J. A. Allen and Chapman 1897 | FR | 57 | 63 | 582 | 5.60 | 10 | 1.96 |

| Phyllostomidae | Dermanura phaeotis phaeotis Miller 1902 | FR | 14 | 14 | 271 | 2.61 | 19 | 3.73 |

| Phyllostomidae | Dermanura tolteca tolteca (de Saussure 1860) | FR | 14 | 15 | 130 | 1.25 | 9 | 1.77 |

| Phyllostomidae | Dermanura watsoni Thomas 1901 | FR | 17 | 15 | 120 | 1.15 | 9 | 1.77 |

| Phyllostomidae | Centurio senex senex Gray 1842 | FR | n/d | 24 | 24 | 0.23 | 1 | 0.20 |

| Phyllostomidae | Chiroderma salvini Dobson 1878 | FR | 23 | s/d | 23 | 0.22 | 1 | 0.20 |

| Phyllostomidae | Platyrrhinus helleri Peters 1866 | FR | n/d | 20 | 79 | 0.76 | 4 | 0.79 |

| Phyllostomidae | Uroderma convexum molaris Davis 1969 | FR | 16 | 18 | 141 | 1.36 | 8 | 1.57 |

| Phyllostomidae | Vampyressa thyone Thomas. 1909 | FR | 12 | s/d | 12 | 0.12 | 1 | 0.20 |

| Phyllostomidae | Vampyrodes major G. M. Allen 1909 | FR | 41 | 26 | 67 | 0.64 | 2 | 0.39 |

| Phyllostomidae | Sturnira hondurensis hondurensis Goodwin. 1940 | FR | 25 | 20 | 346 | 3.33 | 16 | 3.14 |

| Phyllostomidae | Sturnira parvidens Goldman 1917 | FR | 18 | 18 | 3,821 | 36.78 | 222 | 43.61 |

| Vespertilionidae | Bauerus dubiaquercus Van Gelder 1959 | IN | 23 | 22 | 43 | 0.41 | 3 | 0.59 |

| Totals | 10,390 | 100.00 | 509 | 100.00 | ||||

The Shannon-Wiener index of 1.92 indicated relatively moderate species diversity for this study site and sampling effort. Nine species are reported as new additions to the PAFFASIT bat fauna, but are not new records for the region (Centurio senex Gray 1842; Chiroderma salvini Dobson 1878; Carollia perspicillata (Linnaeus 1758); Desmodus rotundus (É.Geoffroy Saint Hilaire 1810); Demanura watsoni (Thomas, 1901); Vampyressa thyone Thomas, 1909; Uroderma bilobatum Peters, 1866; Bauerus dubiaquercus Van Gelder, 1959 and Pteronotus davyi Gray, 1838.

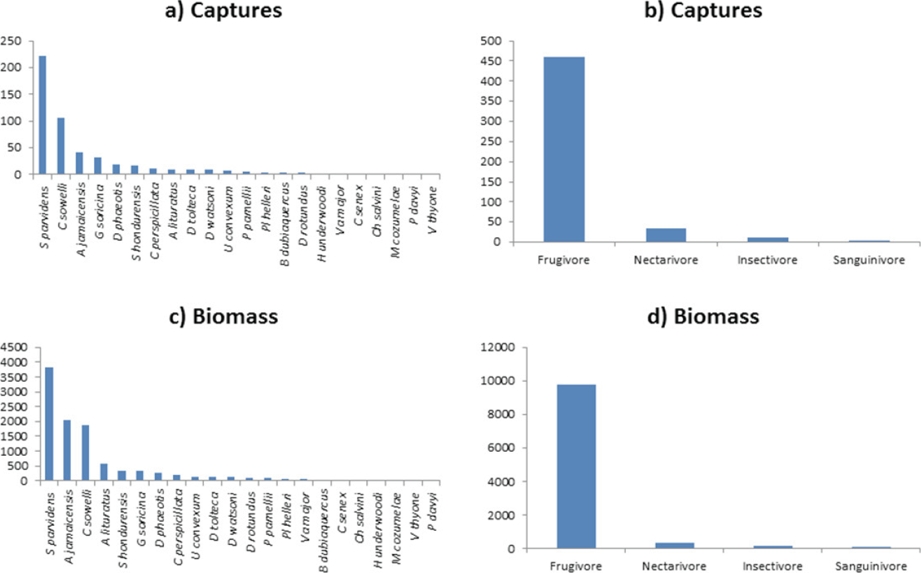

When we consider gross biomass (GB), the top four most abundant species accounted for 76 % of the total biomass (Figure 2). Of these, S. parvidens was the dominant species with regard to captures and alone accounted for 39 % of the total biomass present. Nine other species accounted for less than 100 g each to the total biomass of the captures. Four distinct feeding guilds were established for the individuals captured (Kalko et al. 1996). Frugivores were represented by 16 species belonging to the Phyllostomidae, and this was the dominant feeding guild in terms of numbers of individuals captured (90 %), as well as for biomass estimates (93 %). The nectarivore guild accounted for six percent of the total species captures and three percent of the gross biomass (GB). Insectivores were poorly represented in the sampling and therefore accounted for only one percent of the total captures, but contributed to two percent of the gross biomass (GB). The remaining sanguinivore guild represented by D. rotundus contributed only three individuals to the total number of captures (Figure 2).

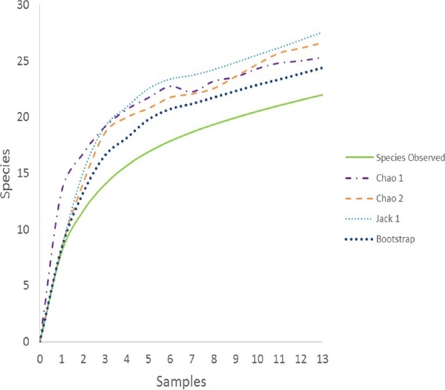

Figure 2 Bat species richness estimation. For abundance-based data we used Chao 1, and for incidence-based data we used Chao2, Jackknives, and Bootstrap. Monthly samples from 1 = November 2007 until 13 = November 2008.

When we consider the accumulation curve of species captured over time and the richness estimators (abundance-based data) of species probably present in PAFFASIT indicated a range from 24 to 26 species diversity for this study site (Figure 3). Each month new species were slowly added to the sample and after nine months of sampling the number of species captured began to reach an asymptote, and no new species were added during the remaining months. The range of species expected went from 24 to 27 species. In Figure 2, we represent graphically the number of captures and the total biomass by species. The left skewedness of these data indicates that a large number of species captured were represented by only a very few individuals, most of them being frugivores. Figure 2 also demonstrated the same skewness when the data are arranged by feeding guilds.

DISCUSSION

Our study revealed, that even though there has been a severe transformation of habitat in the Los Tuxtlas region (Guevara et al. 2006), the presence of a rich understory assemblage of bat species persists on the PAFFASIT study site. From the data presented in the species accumulation curve (Figure 3), we feel confident that essentially all of the understory species present at this site were recorded. Perhaps there were species missed that were extremely rare or only occasional visitors, or species not vulnerable to capture by mist nets. Species such as Chrostopterus auritus (Peters 1856), Lophostoma evotis (W. B. Davis and Carter 1978), Trachops cirrhosus (Spix 1823) and Vampyrum spectrum (Linnaeus 1758), have only limited captures in other studies in the region (Estrada et al. 1993). Several other studies in the northwest portion of the Los Tuxtlas Biosphere reserve which involved more intensive and extensive sampling efforts reported bat assemblages of as many as 33 species captured in mist nets set in forest fragments of varying size (1.0 to 2000 ha; Estrada et al. 1993; Estrada and Coates-Estrada 2001a, b; 2002). On the other hand, the mammal beta diversity reaches high values in Los Tuxtlas. González-Christen (2008), registered 27 Phyllostomid species from 12 localities in the Sierra Santa Martha volcano range only a few kilometers away from PAFFASIT. However, only 16 of these species occurred within tall evergreen rainforest. All species reported for the PAFFASIT site have been documented in the areas surrounding the San Martín Tuxtla and Santa Martha volcanoes, with the exception of Bauerus dubiaquercus (Van Gelder 1959) and Vampyressa thyone not being recorded from the Sierra Santa Martha. It seems most likely that the PAFFASIT site serves as an important refuge and a connection between the faunas of two core areas (volcanoes San Martin Tuxtla and Santa Marta) as they are actually strongly isolated as a consequence of the recent habitat transformation that persists in the Los Tuxtlas (Dirzo and Garcia 1992; Mendoza et al. 2005; Dirzo et al. 2009; Arroyo et al. 2009). At the PAFFASIT site we recorded 34.4 % of the bat species richness documented from Los Tuxtlas Biosphere Reserve.

The bat community we observed at the PAFFASIT site seems to be a simplification of the original mature rainforests in Los Tuxtlas. Alternatively, the nine species reported in this study to be new to the local bat fauna may be due to a more intensive sampling effort over time at this locality. Still another possibility is that they may be an indicator of the responses of bats to the habitat fragmentation of the Los Tuxtlas landscape. We know that species use of various landscape elements depends on the spatial-temporal distribution of resources, connectivity, and configuration of structural landscape elements (Frey-Ehrenbold et al. 2013; Montaño et al. 2015). Either enhancement or decline in species richness can be anticipated. For example, a reduction of species richness was found by Avila-Cabadilla et al. (2009), De la Peña et al. (2012); Falcão (2014); Vleut et al. (2012, 2013). However, Bobrowiec and Gribel (2010) found similar bat richness in three types of secondary vegetation studied in Central Amazonia, but with different species composition in each vegetation type. A study in Amazonia by Klingbeil and Willig (2009) found a higher abundance and species richness in moderately fragmented forests

It is difficult to predict the effects of habitat fragmentation, especially in tropical areas. In our investigation, three species (Sturnira. parvidens, Carollia sowelli and Artibeus jamaicensis) accounted for 73 % of all bats found at PAFFASIT. Similar studies in other tropical areas with anthropogenically modified landscapes, have also found these same species as the most abundant in the understory, probably due to the presence of preferred food resources such as Piper sp. or Solanum sp. (Griscon et al. 2007; Bolívar-Cimé et al. 2014; García-Estrada et al. 2012; Parolin et al. 2016).

In fragmented vegetation scenarios, bats move between the forest edges, mature forest, secondary growth, fruit plantations and grassland. Their response to landscape characteristics depends on the spatial scale, time, vegetation diversity, patch connectivity, and configuration (Medellín et al. 2000; Castro-Luna et al. 2007; Klingbeil and Willig 2010; Frey-Ehrenbold et al. 2013; Bolívar-Cimé et al. 2014; García-Estrada et al. 2012; Arroyo-Rodríguez et al. 2016; McGarigal et al. 2016; Meyer et al. 2016). Species respond distinctively at population, species, guild, and community levels with an array of mid and long-term strategies (Avila-Cabadilla et al. 2012; García-Estrada et al. 2012). These are mediated by differential resource use or interspecific relationships (Cisneros et al. 2016) and changes in behavioral activity patterns (Montaño-Centellas et al. 2015). After 30 years of protection, the understory bat community of PAFFASIT has probably reached a steady state that is actually sustainable.

Some bats are more adaptable to human perturbations and may even flourish under such conditions, but others do not do well in disturbed vegetation. In fragmented habitats, this may explain the absence of species from higher trophic levels within the Phyllostomidae (Castro-Luna et al. 2007). This may be the case of Vampyrum spectrum, Chrostopterus auritus, Lophostoma evotis or Trachops cirrhosus which are reported scarce in the Los Tuxtlas region, but were absent at PAFFASIT. Farneda et al. (2015) pointed out that many “carnivorous” bat species rarely persist in small fragments (<100 ha). Although PAFFASIT is of moderate size, it is apparently not large enough to sustain these species. One possibility is that there is a deficiency of certain functional traits that are needed in order to fulfill the resource requirements of certain species, for example, the diversity of potential prey (Rocha et al. 2016). One other reason could be that the use of mist nets as the only sampling technique could be a limiting factor in the number of bat species documented at the PAFFASIT site.

The understory bat community we detected at our research site was basically composed of Phyllostomatid bats (68 % of the 22 species documented), which probably were favored by the surrounding secondary vegetation. It remains uncertain, however, as to how much if any of this taxonomic bias has been modulated by the forest fragmentation in the surrounding areas. Similar results have been reported for rainforests and tropical dry forests in Mexico and Brazil (Avila-Cabadilla et al. 2009, 2014; Lim and Tavares 2012; De la Peña et al. 2012; Vleut et al. 2012, 2013; Muylaert et al. 2016).

CONCLUSIONS

We confirm the presence of 22 bat species in the understory of the PAFFASIT site. Four of these had especially high numbers of captures and accounted for the majority of all bats captured (Table 1). The most abundant feeding guild among this bat assemblage was frugivory (Table 1). All of the species captured have been previously documented in the Los Tuxtlas region, but the absence of bat species from higher trophic levels is evident. These findings support our hypothesis that the understory bat assemblage in this lowland tropical forest will be dominated by a small percentage of the total bat species present, both in terms of numbers of captures and biomass (Figure 2a, b).

From a conservation perspective, the presence of an abundance of understory frugivorous bats is of great value for their role as seed dispersers not only within the PAFFASIT, but into the remaining mature forests in the region as well as throughout the surrounding anthropogenic landscape. The PAFFASIT also serves as an important connecting link or stepping stone for movements of the bat fauna between the two core protected forest areas of the Los Tuxtlas Biosphere reserve. Moreover, we want to emphasize the importance of the reserve for other conservation purposes at local and regional scales. We need to continue investigations on ecological aspects at PAFFASIT in order to determine which functional traits are fundamentally critical for maintaining the structure of the bat communities in this and other fragmented landscapes.

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)