Introduction

Northeastern Mexico comprises the States of Coahuila, Nuevo León, San Luis Potosí and Tamaulipas, and includes an interesting complex of habitats. One of these is the arid zone located in the boundary with the United States of America, which encompasses two vegetation types: the Chihuahuan desert of western Mexico and the Tamaulipeco thorny scrubland to the east (Rzedowski 2006). The latter has an approximate area of ~200.000 km2 distributed in the States of Coahuila, Nuevo Leon and Tamaulipas, in Mexico, and southern Texas in the United States of America (Jiménez et al. 2012). Although this area is home to a high diversity of plant species, this vegetation type is currently considered as threatened by anthropogenic activities such as cattle raising (intensive/extensive), agriculture and different forest activities that have led to the loss in terms of habitat quality and northeastern Coahuila. The name and location of collection sites are detailed in Annex 1. number of plant species (Alanis et al. 2008; Jiménez et al. 2009; Mora-Donjuán et al. 2014). It is considered that over 90 % of its original surface area has been lost in Texas, while in 30 % is still preserved in northern Mexico (Arriaga et al. 2000). Although no formal studies on the negative effects are currently available, it is likely that the loss mentioned above would undoubtedly jeopardize the fauna present in this type of vegetation, including mammals.

The State of Coahuila de Zaragoza is the third largest political entity in Mexico and provides a variety of suitable habitats for a great diversity of mammals due to its geographical location and unique type of vegetation. This diversity has been studied on a large scale (Sánchez-Cordero et al. 2014), but not at local scales; as a result, some regions are not well documented. In general, studies on mammals in this State are scarce compared with those available for other entities (Guevara-Chumacero et al. 2001; Islas-Sánchez 2014). The knowledge of mammals in Coahuila is summarized in a general inventory (Baker 1956) and some other inventories elaborated for particular groups and regions and reported in the gray literature (Tavizon 1998; Juarez 2006; Mata 2012; Rodríguez 2013; Aguilar Bucio 2014). Another piece of work focuses on the Cuatro Ciénegas Reserve (Contreras-Balderas et al. 2007). This area is one of the regions with the most intense hunting activity in the country, and includes an estimated 4.4 million hectares where hunting is practiced. Coahuila has a record of over one thousand ranches and ejidos with Wildlife Management and Exploitation Units (UMA in Spanish); Acuña, Zaragoza, Guerrero, Villa Union, Jimenez and Nava are the municipalities where the main hunting associations and guides are located (CONABIO 2012).

Due to these intense human activities in the area and the limited local knowledge of the mammalian fauna in the State, it is imperative to produce solid and reliable information concerning the wild populations of mammals that are found at local scales, since the lack of this basic information may result in the inadequate management of natural resources aiming at conservation and sustainable use in the area. For this purpose, this study recorded the richness of wild mammals present in an area comprising two municipalities in northeastern Coahuila, Mexico.

Materials and Methods.

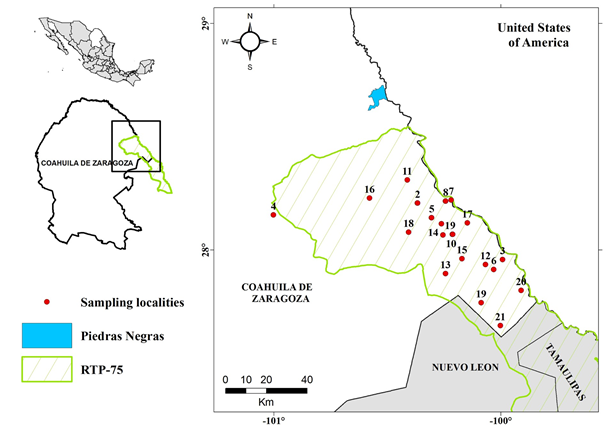

Study area. The sampling area is located 70 km SSE of Piedras Negras in the municipalities of Guerrero and Hidalgo, in northeastern Coahuila, Mexico. It has an area of approximately 1,500 km2 and the dominant vegetation type is the Tamaulipeco thorny scrubland plus small patches of xeric mesquite scrublands, oak forests and natural grassland. The area is located within one of the regions classified by the Mexican government as a priority terrestrial region called Tamaulipeco Scrubland of the Lower Rio Bravo (RTP-75) through the National Commission for the Knowledge and Use of Biodiversity (Figure 1). This scrubland vegetation is dominated by deciduous thorny species most of the year.

Figure 1 Location of the sampling area within the priority terrestrial region named Tamaulipeco Scrubland of the Lower Rio Bravo (RTP-75) located to the SSE of Piedras Negras in northeastern Coahuila. The name and location of collection sites are detailed in Annex 1

The species that predominate are the gavia or huizache (Acacia sp.), paloverde (Cercidium sp.), cenizo (Leucophyllum sp.), mesquite (Prosopis sp.), amargoso (Castela tortuosa) and abrojos (Condalia sp: INEGI 2009; Mora-Donjuán et al. 2014). The physiography of the study area is dominated by prairies and plains, the climate is dry and warm with a mean annual temperature above 22 °C, and with summer and winter rainfall greater than 18 % per year (Arriaga et al. 2000).

Methodology and Data Analysis. Three field trips were conducted in October 2013, March 2014 and June 2014, irregularly distributed in relation to the climatic season, giving a total of 34 days of sampling. Recordings were made using capture and trace methods. The traps used to capture non-flying small mammals (weight ˂ 500 g), were 110 Sherman traps baited with a mixture of oat and vanilla extract placed at random along transects (such as ravines, fallen logs, close to potential burrows and in vegetated areas). The number of transects varied at each sampling site depending on the conditions of each. The age, sex and reproductive status of all specimens captured were recorded before releasing them. Some of these individuals were collected as reference specimens and were prepared conventionally as skin, skeleton, and tissue for deposit and cataloguing in the National Collection of Mammals (CNMA) of the Institute of Biology, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. All captured specimens were handled according to the guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists (Sikes et al. 2011) using the scientific collector license FAUT-0070.

For flying mammals, it was not possible to conduct night captures with mist nets; hence, only daytime searches were carried out in potential shelters such as abandoned buildings, trees and caves. As regards medium-sized and large mammals (weight ˃ 500 g), six Tomahawk traps of various dimensions baited with sardine were placed at distances of at least 400 m. In addition, 16 WVL WF118i_halfshutter camera traps with motion sensor were placed in water bodies or areas identified as animals trails by the continuous identification of tracks. The camera traps were set to operate 24 hours a day and with a minimum delay of 20 seconds between photographs. One day (24 hours) was regarded as one sampling event per camera trap station, considering as independent captures those individual photographs or groups of photographs by species recorded by each camera trap station in a single sampling event (Yasuda 2004). As a supplement, daytime surveys were conducted, each lasting between six to eight hours, across random free transects measuring one to five km long (Wilson and Delahay 2001), where sightings were recorded photographically using conventional cameras. Traces were also searched in these same surveys, including excreta, footprints, and remains such as hair and horns, all of which were identified through specialized guides (Aranda 2012; Elizalde-Arellano et al. 2014). From this evidence, the traces recorded were counted; if more than one was found in the same area, this was considered as a single record to avoid an overestimate of the data (Wilson and Delahay 2001). Bone remains and roadkill specimens of medium-sized and large species were collected, taking samples of tissue, and the skin and skeleton were prepared in the conventional manner for deposit in the biological collection. All specimens were identified using specialized guides (Hall 1981; Alvarez et al. 1994; Villa y Cervantes 2003; Medellín et al. 2008) and by comparisons with CNMA voucher specimens.

To confirm the presence of the species, we used the occurrence index proposed by Boddicker et al. (2002). This index assigns values to the various types of evidence: ambiguous, high-quality and low-quality, and assesses the presence of species from the accumulation of these types of evidence (Table 1). When the cumulative points reach a value of 10, it is concluded that the species is present on the site. The nomenclature used for the species was as proposed by Ramírez-Pulido et al. (2014).

Table 1 Figures used for each type of evidence to calculate the occurrence index. Modified from Boddicker et al. (2002). The “Type of Evidence” column has been added.

The species richness of mammals in the study area was calculated using direct data through the Margalef index with the formula DMg = S - 1/1n N, where S is the number of species and N is the total number of individuals (Moreno 2001). In addition, dominance and evenness were estimated through the Shannon-Wiener and Simpson indices (Moreno 2001) for small, medium-sized and large mammals separately (Monroy-Vilchis et al. 2011).

Results

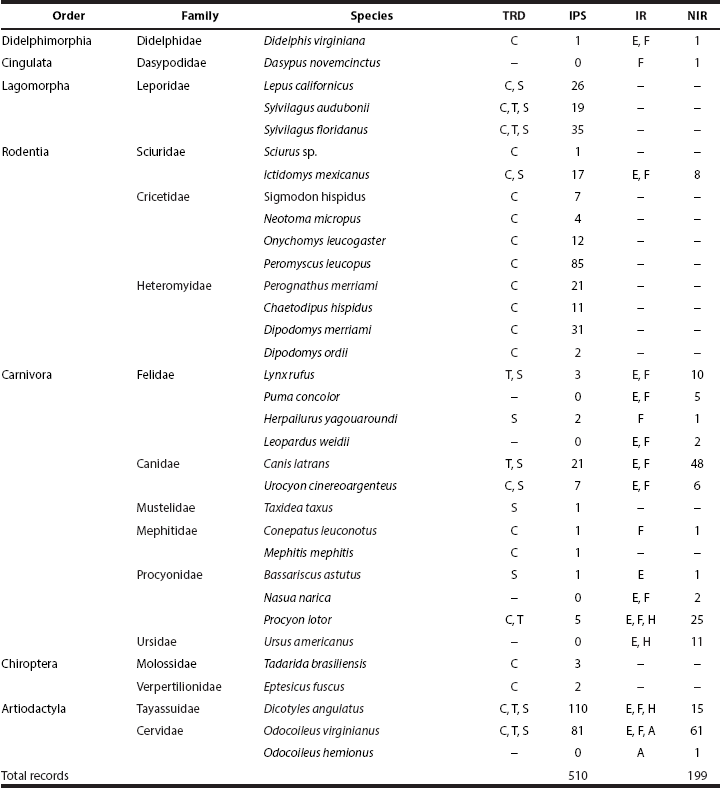

A sampling effort of 34 days resulted in the recording of 33 mammal species in the study area, belonging to 7 orders, 16 families and 30 genera (Table 2). The orders best represented were Carnivora and Rodentia, with 39.4 % and 30.3 % of the total number of species, respectively; the families with the largest number of species were Felidae, Heteromyidae and Cricetidae, with 12.1 % each. A total of 709 records were obtained, 510 of which were direct and 199 indirect.

Table 2 Mammals recorded in the municipalities of Guerrero and Hidalgo in northeastern Coahuila; the type of record for each one is shown. Direct records: C = capture, T = camera trapping, and S = sighting; indirect records: E = excreta, F = footprints, H = hair, A = antlers. Direct records (DR), number of individuals per capture, photograph or sighting (IPS). Indirect records (IR) and number of indirect records (NIR).

The small mammals captured (196 individuals) correspond to the orders Rodentia and Chiroptera, belonging to five families and 12 species. Ten species of rodents were recorded, the species with the highest number of records being Peromyscus leucopus, Dipodomys merriami and Perognathus merriami (85, 31 and 21 individuals, respectively). One specimen of the genus Sciurus could not be identified to species because it was a poorly preserved roadkill specimen. On the other hand, the bat species found in shelters were Eptesicus fuscus within cavities at the base of a dead tree, and Tadarida brasiliensis inside an abandoned building.

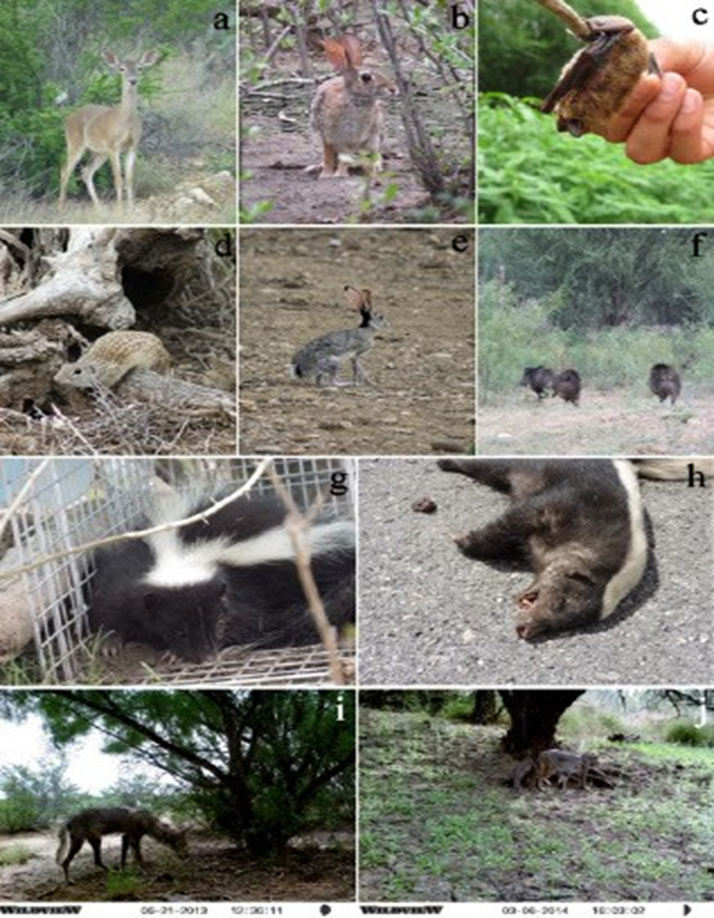

The medium-sized and large mammals (505 records in total) belong to five orders, 11 families and 21 species. The species with the highest number of direct records were Dicotyles angulatus (110), Odocoileus virginianus (81) and Sylvilagus floridanus (35, Figure 2). The occurrence index by Boddicker et al. (2002) confirmed the presence of all species except Dasypus novemcinctus, Puma concolor, Conepatus leuconotus, Nasua narica and Ursus americanus, which were identified by indirect methods only.

Figure 2 Some species recorded by sighting and camera traps in the study area. A) Odocoileus virginianus, B) Sylvilagus audubonii, C) Eptesicus fuscus, D) Ictidomys mexicanus, E) Lepus californicus, F) Dicotyles angulatus, G) Mephitis mephitis, H) Conepatus leuconotus, I) Canis latrans, and J) Lynx rufus.

A total of 39 specimens were deposited in the National Collection of Mammals (CNMA; Annex 1). Of the total species recorded, four are under some protection category by the Mexican government according to NOM-059-2010 (SEMARNAT 2010): Herpailurus yagouaroundi and Taxidea taxus as "threatened", and Ursus americanus and Leopardus weidii in the "special protection” category. On the other hand, the species Lynx rufus, Puma concolor, Herpailurus yagouaroundi, and Ursus americanus are listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), while Leopardus weidii is listed in Appendix I (2016). The only endemic species recorded was Ictidomys mexicanus.

The Margalef index (5.13) revealed that the total diversity in the area is high. The Simpson index for small mammals (0.241) points to a greater dominance of the most abundant species relative to medium-sized and large mammals (0.215). On the other hand, the Shannon-Wiener index showed that the evenness between species was lower for small mammals (1.821) relative to medium-sized and large mammals (1.858).

Discussion

Despite the fact that Mexico still preserves 30 % of the surface area originally covered with Tamaulipeco thorny scrubland, it is considered that there is an insufficient knowledge about the fauna that inhabits it (Arriaga et al. 2000). In addition, the low number of studies that are carried out in Coahuila due to safety issues and the low number of protected natural areas in the state highlight the importance of this work.

Coahuila is home to 107 species of mammals: 80 terrestrial and 27 flying ones (Sánchez-Cordero et al. 2014). In all, 31.8 % of the mammal fauna of the State was recorded in the study area, demonstrating the high diversity in the area supported by the Margalef index (5.13). The three rodent species with the highest number of records are widely distributed species. P. leucopus is highly tolerant to various environmental conditions such as those that characterize the study area, while D. merriami is considered to be locally abundant in other studies (Castillo 2005; Chávez and Espinosa 2005; Frisch-Jordan and Arita 2005).

Ictidomys mexicanus was the only endemic species recorded (Ramírez-Pulido et al. 2014), with only three individuals captured. The number of sightings (13) was higher, supported by indirect records including excreta and burrows; this suggests a high abundance of the species in the area. This is consistent with other studies that indicate that this species is relatively abundant across its areas of distribution (Ceballos and Galindo 1984; Valdez and Ceballos 1991).

The daytime searches of bat shelters detected an abandoned building used as a warehouse that was inhabited by a large colony of at least 15 individuals of Tadarida brasiliensis. Due to the difficulty of capturing all individuals and that this a "segregationist” species, i. e., it shares its shelters with just a few species (Arita 1993), it is considered that the whole colony belonged to this species only. The second Chiroptera species recorded was Eptesicus fuscus with about four individuals observed and captured inside cavities at the base of a dead tree, with no other structure close to it. This type of shelter is characteristic of the species (Tellez-Giron 2005).

The occurrence index by Boddicker et al. (2002) did not confirm the presence of five species (Dasypus novemcinctus, Nasua narica, Conepatus leuconotus, Puma concolor and Ursus americanus), since these were detected through a low number of indirect records. However, the traces observed possess particular characteristics that facilitate their identification. D. novemcinctus leaves a characteristic and unmistakable trail of footprints; the unique features of these fingerprints derive from fingers being short with long thick claws with rounded tips; in addition, in some cases the drag of the tail leaves a trace in soil (Aranda 2012). In P. concolor, the tracks could only be misidentified with those of the jaguar (Panthera onca) because of the similar size of the fingerprints. However, it was considered that the habitat is more favorable for the cougar, in addition to the fact that several specimens of this species have been observed by local inhabitants and workers. The footprints of C. leuconotus are similar to those of C. semistriatus, but these two species have supplementary distributions and the study area coincides with the distribution of C. leuconotus (Aranda 2012). This was confirmed by a roadkill individual found in a survey trip to the site (Figure 2H). In the case of N. narica and U. americanus, evidence records are scarce. In the case of N. narica, these comprise only two traces; in the case of U. americanus, in presumed excreta. The margay (Leopardus weidii) was recorded based on two prints that match the characteristics and size of the species, although these can be confused with domestic cat traces (Aranda 2012), no margay specimens were observed in the area.

The large number of records of Dicotyles angulatus (n = 110) and Odocoileus virginianus (n = 81) is due to the fact that the study area is located within a hunting zone where these are the main species used. A skull and vertebrae of one specimen were collected which were subsequently identified as a mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus). The identification is based on the comparison with specimens in the National Collection of Mammals, where the size of the lacrimal bone allowed the identification as O. hemionus. The mule deer lives in isolated geographical patches, and hunting is permitted under the "special license" modality (Galindo-Leal 1993). However, the hunting ranches in the area do not report the mule deer among the game species used.

Hunting is an activity with strong cultural roots that led to the disappearance or marked decline of the local populations of some species; as a result, the mule deer has been subject to strict regulation, including the creation of hunting zones (SAHR 1993). This type of scheme has been widely popularized in the northern States of Mexico and covers an area of more than 18 million hectares, making it one of the most important sources of income in the region. Recently, hunting has been linked to a number of benefits for conservation because it allows the controlled use of the resource in extensive areas and represents a significant income that allows managing the area to preserve its environmental quality in terms of vegetation that is favorable for the presence of game animals (2010 Rengifo-Gallego). The maintenance or establishment of a suitable habitat for game species (natural vegetation within the agricultural matrix, mosaic landscape or boundaries), as well as the supply of food and water, seem to favor other species as well (Arroyo et al. 2013). In our study area, the management and conservation of the habitat benefits not only the game species but also the rest of species present in the area. This is reflected in the high number of species recorded and in the presence of large carnivores such as the black bear (U. americanus) and the cougar (P. concolor).

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)