Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

versión impresa ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.14 no.79 México sep./oct. 2023 Epub 06-Oct-2023

https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v14i79.1340

Scientific article

Assessment of a reforestation and a regeneration of the Tamaulipan Thorny Scrub at Northeastern Mexico

1Facultad de Ciencias Forestales. Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. México.

2Gestión Estratégica y Manejo Ambiental, S. C. (GEMA, S. C.). México.

3Biólogos y Silvicultores Forestales por el Ambiente A. C. (BIOSFERA, A. C.). México.

The ecosystems in northeastern Mexico have become degraded, and, therefore, it has been necessary to develop strategies to restore them. The objectives of this study were to estimate the survival and composition of a reforestation with native species three years after its establishment, as well as to assess the floristic composition and ecological parameters of the Tamaulipan Thorny Scrub (MET) 11 years after its reconversion for hunting use. Based on their ecological parameters, the regenerated vegetation was characterized into two strata, and their diversity indexes were calculated (Shannon-Wiener, Margalef, and Pretzsch). The survival and ecological parameters of the established species were estimated for reforestation purposes. The most important species within the regeneration were characteristic of early successional stages, following anthropogenic activities. The highest abundance of families and individuals was concentrated in the Fabaceae and Poaceae families; the former, represented by the same species successfully established in reforestation, and the latter, by invasive herbaceous taxa. Within reforestation, Prosopis glandulosa, Diospyros texana, Cordia boissieri, Ebenopsis ebano, Vachellia rigidula, and Havardia pallens had survival rates of 76.92, 50.0, 40.0, 38.46, 24.24, and 20.0 %, respectively; the rest of the species had 0 %. The results obtained are relevant for decision-making in forest management at the TTS, as well as for the monitoring of this community in its various successional stages.

Key words Hunting activities; frost damage; desertification; diversity indexes; post-livestock; ecological restoration

Debido a la degradación en los ecosistemas del noreste de México, ha sido necesario desarrollar estrategias para restaurarlos. Los objetivos del presente estudio fueron estimar la supervivencia y composición de una reforestación con especies nativas, tres años después de su establecimiento, así como evaluar la composición florística y parámetros ecológicos del Matorral Espinoso Tamaulipeco (MET) a 11 años de su reconversión para aprovechamiento cinegético. Se caracterizó la vegetación regenerada a través de sus parámetros ecológicos en dos estratos, y se realizó el cálculo de sus índices de diversidad (Shannon-Wiener, Margalef y Pretzsch). Para la reforestación se estimó la supervivencia y parámetros ecológicos de las especies establecidas. Las especies con mayor importancia dentro de la regeneración fueron características de etapas de sucesión temprana, posterior a actividades antropogénicas. La mayor abundancia de familias e individuos se concentró en las familias Fabaceae y Poaceae, la primera representada por las mismas especies establecidas con éxito en la reforestación, y la segunda por taxones herbáceos de carácter invasor. Dentro de la reforestación, Prosopis glandulosa, Diospyros texana, Cordia boissieri, Ebenopsis ebano, Vachellia rigidula y Havardia pallens presentaron porcentajes de supervivencia de 76.92, 50.0, 40.0, 38.46, 24.24 y 20.0 %, respectivamente, y el resto de las especies registraron 0 %. Los resultados obtenidos son de relevancia para la toma de decisiones en el manejo forestal del MET, así como para el monitoreo de esta comunidad en sus diferentes etapas sucesionales.

Palabras clave Actividades cinegéticas; daño por heladas; desertificación; índices de diversidad; posganadería; restauración ecológica

Introduction

In Mexico, arid and semi-arid zones make up 60 % of its territory (Pontifes et al., 2018). The importance of studying them lies in the extreme conditions that affect their ecosystems, such as torrential rains, droughts, and frosts, which limit the growth and development of the flora (Filio-Hernández et al., 2019). Among its plant communities, the Tamaulipan Thorny Scrub (MET, for its acronym in Spanish) stands out as the most abundant in the northeastern region of Mexico (Patiño-Flores et al., 2021). It covers an area of approximately 125 000 km2, distributed across the states of Tamaulipas, Nuevo León and Coahuila in Mexico, and south of Texas in the United States of America (Alanís et al., 2013). It grows in warm and semi-warm climates, at altitudes of 200 to 500 m, on flat land, plateaus, and hills, in deep, clayey soils of the Vertisol type (Molina-Guerra et al., 2019; Alanís-Rodríguez et al., 2021). The heterogeneity of edaphic and climatological conditions within the distribution area has given rise to a great variety of taxonomic assemblages, which become manifest in the diversity, richness, cover, height, and density among plant species (Pequeño-Ledezma et al., 2017). Ecosystem services include carbon sequestration, erosion reduction, improved water infiltration, scenic beauty, and wildlife habitat (Molina-Guerra et al., 2023).

The vegetation of the MET is harvested for timber, handicraft, ornamental, medicinal, and food purposes (Leal-Elizondo et al., 2018), while most of the land is used for rainfed agriculture and both intensive and extensive livestock farming (Mora et al., 2013). Today, the area of land clearing has increased due to urbanization (Alanís-Rodríguez et al., 2015), fuel and mineral exploitation (Marroquín-Castillo et al., 2017; Molina-Guerra et al., 2019), and installation of infrastructure for power generation (Mata et al., 2022), among other factors.

According to the National Forest Commission (Conafor, 2015), the clearing of forest land for the development of these economic activities has an impact on the ecosystem that must be balanced through ecological compensation actions. These measures can be implemented through reforestation with native species in areas that show some state of degradation, if established vegetation is maintained over the long term, it can lead to ecological succession and improve ecosystem conditions (Venegas, 2016). One way to increase their chances of permanence is to carry out reforestation in areas where low-impact economic activities are developed, and at the same time it is convenient for the owners to increase native vegetation (Martín et al., 2022). An example of this is hunting activities (Serna-Lagunes et al., 2013), which boomed nationwide in the first decade of the 2000s, mainly in the states of Nuevo León, Coahuila, Tamaulipas, Sonora and Chihuahua (Gallina-Tessaro et al., 2009). Specifically, the hunting exploitation of the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus Zimmermann) depends on a vegetative cover of at least 2.5 m in height for protection from predators and adverse weather conditions (Villarreal, 2014).

Research conducted at the MET for hunting purposes has focused mainly on the estimation of production indicators such as biomass, carrying capacity, and nutritional importance (Domínguez et al., 2012; González-Saldívar et al., 2014), as a result, studies aimed at assessing the vegetation composition within authorized wildlife conservation management units (UMA, for its acronym in Spanish) are scarce (Cantú et al., 2011; Alanís et al., 2015). There are no documented cases regarding the assessment of reforestations in the MET with this type of harvesting. For this reason, the objectives of the present research were as follows: (1) To estimate the survival and composition of a reforestation site, as part of an environmental offset, three years after its establishment, and 2) To assess the floristic composition and ecological parameters of the MET 11 years after its reconversion for hunting use.

Materials and Methods

Study area

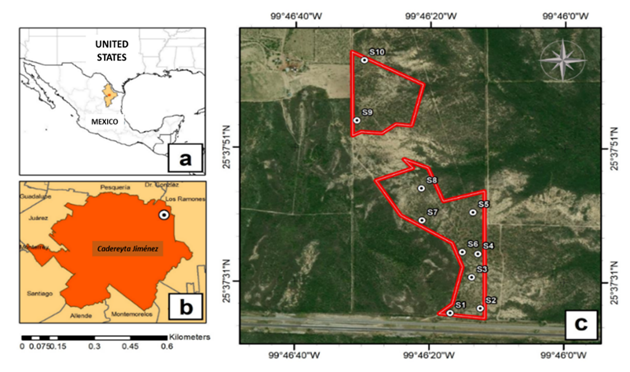

The study area is located in Cadereyta Jiménez municipality, Nuevo León. The location coordinates are 99°46'31.15" W and 25°39'3.27" N, and 99°46'31.26" W and 25°37'11.92" N (GPS model 10 eTrex®), at 252 masl, with an area of 22.66 ha (Figure 1). The climate is classified as warm semi-arid BS1(h')w, with a mean annual temperature and precipitation of 22 to 24 °C and 600 to 800 mm, respectively (García, 2004; Cuervo-Robayo et al., 2015a; Cuervo-Robayo et al., 2015b). The soils are classified as Kastañozem and Vertisol (INEGI, 2013). The site has a history of logging of timber species (Prosopis glandulosa Torr., Ebenopsis ebano (Berland.) Barneby & J. W. Grimes, and Helietta parvifolia (A. Gray ex Hemsl.) Benth.) and extensive livestock farming (cattle). As of 2010, these activities ceased in order to make room for the hunting of the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and the collared wild boar (Pecari tajacu Linnaeus).

Reforestation activities

Reforestation activities were carried out as a result of the implementation of a reforestation program requested for environmental compensation for the establishment of a thermoelectric power plant in El Carmen municipality, Nuevo León. 16 woody species native to the MET were used to enhance diversity within the study site, having been selected based on taxonomic records of the municipality corresponding to primary and secondary vegetation (López and Pando, 2014; Rodríguez-Rojas et al., 2017). Seeds were collected during the spring of 2017 and stored in airtight containers inside a refrigerator (model AT9007G, Acros®) at a temperature of 13 °C. Subsequently, in September 2017 they were germinated; for this purpose, polystyrene trays (Hidro Enviroment®) were used (capacity of 200 cavities of 15 cm3 and caliber of 1 mm), the average sprouting time was 8 to 15 days. Germinated seedlings were transferred to 500 mL polyethylene bags, which were filled to 95 % of their capacity with a substrate mixture (70-30-10: natural soil, 22 mm pumice stone, and perlite mineral). The individuals were placed in beds under 40 % shade cloth; they were irrigated weekly for a period of 6 months. The seedlings were germinated and developed in the forest nursery of the company GEMA S. C., in Linares municipality, Nuevo León.

Planting was carried out in April 2018, considering the spring rains, prior to the summer temperature increase (ClimateData, 2023; Servicio Meteorológico Nacional, 2006). Planting density was 1 283 individuals per hectare with a random distribution within the entire area of the property (22.66 ha). A three-bowl design was utilized, this is a technique recommended to minimize soil dragging and at the same time take advantage of the runoff in the area (Conafor, 2010).

The seedlings used had an average height of 0.35 m (Conafor, 2010), therefore, they were placed inside circular stocks with a depth of 0.50 m and a diameter of 0.35 m. Previously, fine-grained agricultural hydrogel (Hydrogel MX) dissolved in water was added at a concentration of 3 g L-1, following the supplier's recommendations (Maldonado-Benitez et al., 2011). Furthermore, a phytoregulator rooting powder (Raizone-Plus® Fax, 1.5 mg L-1) was added to promote root growth and heal any wounds that may have been made during the planting process. At the end of planting, an initial irrigation of 25 L of water per individual was applied to allow the plant to adapt to the soil conditions. Each individual was secured with wooden stakes, and a 0.66 m long by 0.35 m high tubular protector made of high-density polyurethane was placed.

Quarterly maintenance activities, consisting in irrigation by pipe and hose (10 L per seedling) and replacement of dead plants at 100 %, were carried out from May 2018 to May 2020. In addition, herbaceous plants were removed monthly with a machete within 1 m2 around the plant for a period of four months. The seedlings used for the substitution were developed under the same procedure as the original ones, until they reached a height range of 0.35-0.50 m. However, it was not possible to use the same species in all cases, and, therefore, the evaluation was made after the maintenance activities were completed.

Reforestation survival analysis

In August 2021, the survival of the plantation was evaluated based on the total number planted until May 2020. A sampling design adapted from Ramírez (2011) was used resulting in the establishment of 10 circular sampling plots (sampling fraction=1.19 %) with a surface area of 250 m2 (radius of 8.92 m). The distance between sites was 150 m, estimated based on the equations of Schlegel et al. (2001). At each site, the survival and cover (N-S and E-W) of each of the planted individuals were assessed; they were found to differ from those obtained with natural regeneration due to the previous use of tubular protectors. Measurements were made with a 10 m Truper® flexometer. Survival, both overall and by species, was estimated with the Equation (1) (García, 2011):

Where:

%S = Survival rate

Pv = Number of living individuals

P = Total number of live and dead plants

Assessment of natural regeneration of the MET

The same circular plots utilized for the survival analysis were used to characterize the natural regeneration of the MET. The vegetation was divided into two strata: the tall stratum, consisting of vegetation with woody stems (D 1.5 ≥1 cm), and Rosaceae and succulents counted within the 250 m2 circular area. The low herbaceous stratum, which included herbaceous species, was counted in a 1 m2 quadrat at the center of each circular plot. Stimates 9.1 software (Colwell, 2023) was used to verify that each stratum was fully sampled by means of species accumulation curves and through the evaluation of two non-parametric species richness estimators ―Chao 2 and Jackknife 1― recommended for small sampling units (Hortal et al., 2006). The completeness of each survey was calculated based on the ratio between the observed richness and the estimated total richness (Willott, 2001).

In both strata, the horizontal cover of each individual (N-S and E-W) and the height was measured using a 30 m tape (model TFC 30ME, Truper®). Plant species were identified with the help of flora catalogs and taxonomic keys (Alanís et al., 2011). The ecological parameters of the recovered vegetation were analyzed by calculating abundance, dominance, frequency in absolute and relative form, as well as the Importance Value Index (IVI) of Whittaker (1972) and Mueller-Dombois and Ellenberg (1974). Species diversity was evaluated through the Shannon-Wiener Index (H') (Shannon and Weaver, 1949), which indicates the relative abundance of species. The Margalef index (D Mg ) (Clifford and Stephenson, 1975) was used to calculate the wealth of species. The vertical structure by sampling stratum was also analyzed using the Pretzsch Index, which categorizes the vertical structure into three strata: stratum I (high) refers to the interval between 80 and 100 %, in which 100 % is represented by the highest individual in the sampling stratum; stratum II (medium), to a 50-80 % interval, and stratum III (low), to a range of values of 0-50 % (Pretzsch, 2009).

Results and Discussion

Reforestation survival

In the survival assessment, 15 months after suspending maintenance activities in the plantation, the presence of 407 live individuals per hectare was estimated, which is equal to a 31.72 % survival rate, based on the initial plantation density. The successfully established species were Prosopis glandulosa, Vachellia rigidula (Benth.) Seigler & Ebinger, Ebenopsis ebano, Cordia boissieri A. DC., Diospyros texana Scheele and Havardia pallens (Benth.) Britton & Rose. The rest of the species (10) did not survive (Table 1).

Table 1 Values per hectare of planted individuals, live individuals per hectare, survival and cover in the reforestation area.

| Species | Planted individuals ha-1 |

Living individuals ha-1 |

Survival (%) |

Mean cover (m2 ha-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prosopis glandulosa Torr. | 49 | 37 | 76.92 | 0.66±0.08 |

| Diospyros texana Scheele | 242 | 121 | 50.00 | 0.58±0.09 |

| Cordia boissieri A. DC. | 161 | 64 | 40.00 | 0.23±0.08 |

| Ebenopsis ebano (Berland.) Barneby & J. W. Grimes | 215 | 82 | 38.46 | 0.66±0.08 |

| Vachellia rigidula (Benth.) Seigler & Ebinger | 104 | 25 | 24.24 | 0.55±0.08 |

| Havardia pallens (Benth.) Britton & Rose | 62 | 12 | 20.00 | 0.66±0.08 |

| Ehretia anacua (Terán & Berland.) I. M. Johnst. | 189 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Senegalia berlandieri (Benth.) Britton & Rose | 87 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Celtis pallida Torr. | 42 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Parkinsonia aculeata L. | 38 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Vachellia farnesiana (L.) Wight & Arn. | 31 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Erythrostemon mexicanus (A. Gray) Gagnon & G. P. Lewis | 22 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Senegalia greggii (A. Gray) Britton & Rose | 18 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Condalia hookeri M. C. Johnst. | 12 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Leucophyllum frutescens (Berland.) I. M. Johnst. | 10 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Yucca filifera Chabaud | 1 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Total | 1 283 | 407 | 31.72 |

This survival rate, which is lower than that obtained in other reforestations in the MET (Table 2), can be attributed to several factors, one of the main factors is the extreme weather prevailing in northeastern Mexico (Jurado et al., 2006).

Table 2 Previous survival assessment studies of the Tamaulipan Thorny Scrub (MET).

| Authors and year of publication |

Municipality and state |

Objective of the study | Survival rate (%) | Establishment time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jurado et al. (2006) | Cd. Victoria, Tamaulipas | Identification of species for ecological restoration | Presented in graphs by species | 1 year |

| López y López (2013) | Linares, Nuevo León | Ornamental plantation | 70.0 | 16 years |

| Foroughbakhch et al. (2014) | Linares, Nuevo León | Identification of species for ecological restoration | 99.11 | 5 years |

| Vega-López et al. (2017) | Pesquería, Nuevo León | Identification of species for ecological restoration | 51.6 | 1 year |

| Gutiérrez-Barrientos et al. (2022) | Pesquería, Nuevo León | Use of drones for forest plantation monitoring | 76.07 | Not specified |

| Patiño-Flores et al. (2022) | Pesquería, Nuevo León | Reforestation of a degraded area | 49.4 | 41 months |

| Mata et al. (2022) | Los Ramones, Nuevo León | Reforestation of a degraded area | 28.7 | 31 months |

Between February 13th and 20th, 2021, a temperature drop as low as -5 °C (Meteored, 2023) occurred over much of the southern United States and northern Mexico (Yang and Liu, 2023). Previous studies have reported negative effects on shrubland ecosystems due to frost (Lonard and Judd, 1991; Bojórquez et al., 2021; Mata et al., 2022); damage occurs inside the plant due to the formation of ice in the intercellular spaces, which causes the rupture or dehydration of the cell (Curzel and Hurtado, 2020).

Some MET species have developed adaptive mechanisms that allow them to survive the incidence of drought or frost (González et al., 2004). Those individuals that managed to establish themselves in the reforestation, belonging to the species Cordia boissieri and Diospyros texana, have narrow ducts that prevent the cavitation process during the rise or fall of temperatures, and the water moves through them (Maiti et al., 2016). Prosopis glandulosa exhibits a decrease in leaf area under water stress conditions (Qin et al., 2018), as well as deep roots that allow it to reach groundwater (Johnson et al., 2018).

Ebenopsis ebano has a thick cuticle that reduces water loss through transpiration (González et al., 2017a), and its high content of chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b is associated with a high photosynthetic capacity during dry seasons (Maiti et al., 2016). Likewise, Havardia pallens increases its chlorophyll content, probably as an adaptation to the winter season (González et al., 2017b). It has been shown that individuals of the species Vachellia rigidula cope with lack of moisture by increasing their water potential (González et al., 2004).

In the study area, the cover of the herbaceous stratum had a higher dominance value than the tree-shrub vegetation of both the reforestation and the regeneration (Tables 2 and 3). Similar results are presented by Albrecht et al. (2022) in an area invaded by exotic grasses, 23 years after its reforestation with MET species, where E. ebano and P. glandulosa had the lowest mortality. However, E. ebano and H. pallens, two of the species with the greatest cover, have been cited as taxa that prefer a closed canopy for growth (Jurado et al., 2006).

Table 3 Ecological parameters of MET regeneration and their relative values.

| Family | Scientific name | Abundance | Cover | Frequency | Relative Abundance |

Relative Dominance |

Relative Frequency |

IVI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High stratum | ||||||||

| Fabaceae | Vachellia rigidula (Benth.) Seigler & Ebinger | 764 | 5.51 | 10 | 23.46 | 5.56 | 7.63 | 12.22 |

| Scrophulariaceae | Leucophyllum frutescens (Berland.) I. M. Johnst. | 344 | 4.73 | 9 | 10.57 | 4.77 | 6.87 | 7.40 |

| Celastraceae | Schaefferia cuneifolia A. Gray | 324 | 3.88 | 8 | 9.95 | 3.91 | 6.11 | 6.66 |

| Rhamnaceae | Rhamnus humboldtiana Schult. | 236 | 4.03 | 9 | 7.25 | 4.06 | 6.87 | 6.06 |

| Fabaceae | Cercidium macrum I. M. Johnst. | 120 | 7.80 | 8 | 3.69 | 7.87 | 6.11 | 5.89 |

| Euphorbiaceae | Jatropha dioica Sessé ex Cerv. | 272 | 1.87 | 9 | 8.35 | 1.89 | 6.87 | 5.70 |

| Verbenaceae | Lantana camara L. | 236 | 2.57 | 9 | 7.25 | 2.59 | 6.87 | 5.57 |

| Fabaceae | Eysenhardtia texana Scheele | 116 | 4.93 | 8 | 3.56 | 4.97 | 6.11 | 4.88 |

| Cordiaceae | Cordia boissieri A. DC. | 76 | 6.15 | 7 | 2.33 | 6.20 | 5.34 | 4.63 |

| Solanaceae | Lycium berlandieri Dunal | 124 | 3.75 | 8 | 3.81 | 3.78 | 6.11 | 4.57 |

| Rubiaceae | Randia rhagocarpa Standl. | 136 | 4.09 | 6 | 4.18 | 4.12 | 4.58 | 4.29 |

| Oleaceae | Forestiera angustifolia Torr. | 72 | 5.21 | 6 | 2.21 | 5.26 | 4.58 | 4.02 |

| Asparagaceae | Yucca filifera Chabaud | 44 | 6.47 | 4 | 1.35 | 6.53 | 3.05 | 3.64 |

| Fabaceae | Havardia pallens (Benth.) Britton & Rose | 32 | 5.46 | 4 | 0.98 | 5.51 | 3.05 | 3.18 |

| Zygophyllaceae | Guaiacum angustifolium Engelm. | 124 | 2.65 | 3 | 3.81 | 2.67 | 2.29 | 2.92 |

| Cactaceae | Cylindropuntia leptocaulis (DC.) F. M. Knuth | 64 | 2.13 | 5 | 1.97 | 2.14 | 3.82 | 2.64 |

| Fabaceae | Chamaecrista greggii (A. Gray) Pollard ex A. Heller | 20 | 3.03 | 5 | 0.61 | 3.06 | 3.82 | 2.50 |

| Fabaceae | Vachellia farnesiana (L.) Wight & Arn. | 16 | 4.85 | 2 | 0.49 | 4.89 | 1.53 | 2.30 |

| Euphorbiaceae | Bernardia myricifolia (Scheele) S. Watson | 8 | 4.10 | 1 | 0.25 | 4.14 | 0.76 | 1.71 |

| Verbenaceae | Lippia graveolens Kunth | 40 | 3.00 | 1 | 1.23 | 3.03 | 0.76 | 1.67 |

| Fabaceae | Prosopis glandulosa Torr. | 4 | 3.60 | 1 | 0.12 | 3.63 | 0.76 | 1.51 |

| Euphorbiaceae | Croton incanus Kunth | 40 | 1.59 | 2 | 1.23 | 1.60 | 1.53 | 1.45 |

| Verbenaceae | Aloysia macrostachya (Torr.) Moldenke | 8 | 3.20 | 1 | 0.25 | 3.23 | 0.76 | 1.41 |

| Verbenaceae | Lantana achyranthifolia Desf. | 4 | 2.00 | 1 | 0.12 | 2.02 | 0.76 | 0.97 |

| Asparagaceae | Agave lechuguilla Torr. | 4 | 1.80 | 1 | 0.12 | 1.82 | 0.76 | 0.90 |

| Cactaceae | Homalocephala texensis (Hopffer) Britton & Rose | 8 | 0.50 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 1.53 | 0.76 |

| Cactaceae | Ancistrocactus scheeri (Salm-Dyck) Britton & Rose | 20 | 0.24 | 1 | 0.61 | 0.24 | 0.76 | 0.54 |

| Total | 3 256 | 99.14 | 131 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | |

| Low stratum | ||||||||

| Poaceae | Bouteloua gracilis (Kunth) Lag. ex Griffiths | 120 000 | 137.50 | 9 | 45.45 | 7.80 | 20.00 | 24.42 |

| Poaceae | Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. | 21 000 | 408.33 | 4 | 7.95 | 23.17 | 8.89 | 13.34 |

| Acanthaceae | Ruellia nudiflora (Engelm. & A. Gray) Urb. | 40 000 | 115.38 | 7 | 15.15 | 6.55 | 15.56 | 12.42 |

| Convolvulaceae | Evolvulus alsinoides (L.) L. | 32 000 | 80.16 | 7 | 12.12 | 4.55 | 15.56 | 10.74 |

| Ehretiaceae | Tiquilia canescens (A. DC.) A. T. Richardson | 15 000 | 235.00 | 4 | 5.68 | 13.33 | 8.89 | 9.30 |

| Poaceae | Melinis repens (Willd.) Zizka | 5 000 | 292.00 | 2 | 1.89 | 16.57 | 4.44 | 7.64 |

| Malvaceae | Meximalva filipes (A. Gray) Fryxell | 6 000 | 63.33 | 3 | 2.27 | 3.59 | 6.67 | 4.18 |

| Heliotropiaceae | Heliotropium angiospermum Murray | 1 000 | 165.00 | 1 | 0.38 | 9.36 | 2.22 | 3.99 |

| Malvaceae | Malvastrum sect. coromandelianum (L.) Garcke | 3 000 | 71.67 | 3 | 1.14 | 4.07 | 6.67 | 3.96 |

| Asteraceae | Thymophylla pentachaeta (DC.) Small | 8 000 | 76.25 | 2 | 3.03 | 4.33 | 4.44 | 3.93 |

| Euphorbiaceae | Euphorbia aleppica var. prostata Kasapligil | 12 000 | 47.92 | 2 | 4.55 | 2.72 | 4.44 | 3.90 |

| Bixaceae | Cochlospermum wrightii (A. Gray) Byng & Christenh | 1 000 | 70.00 | 1 | 0.38 | 3.97 | 2.22 | 2.19 |

| Total | 264 000 | 1,763.54 | 45 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | |

Abundance (N ha-1), Cover (m2 ha-1), Frequency (N) and Dominance (%) ranked from highest to lowest Importance Value Index (IVI %).

Characterization of the regenerated vegetation of MET

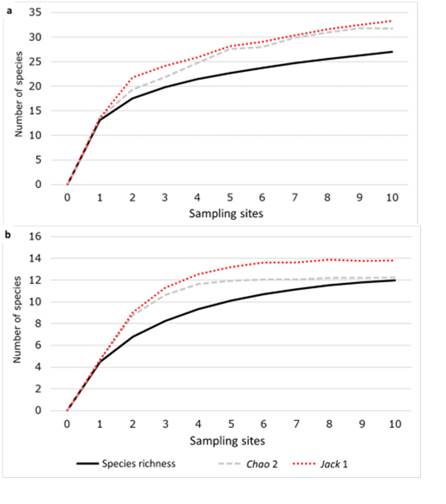

The species accumulation curves showed a non-asymptotic increasing trend, indicating that a higher number of taxa was expected in both strata (Figure 2). Sampling completeness varied between high and low strata (Chao 2=85.09 % and 98.12 %; Jackknife 1=81.08 % and 86.96 %), as well as estimated richness between estimators (Chao 2=32 and 12 species; Jackknife 1=33 and 14 species). There is no definitive estimator for all situations, but the Jackknife 1 estimator is the most commonly accepted (González-Oreja et al., 2010). Arboreal-shrub communities are the most studied for the MET, with richness records of 30 to 40 species (Alanís et al., 2015), which denotes that the sampling effort has been acceptable for this parameter.

a = High stratum; b = Low stratum.

Figure 2 Species accumulation curves with two nonparametric estimators (Chao 2 and Jackknife 1).

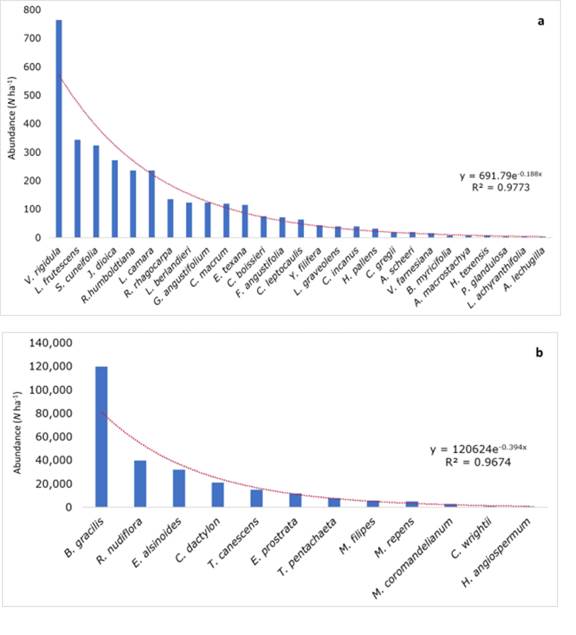

The plant community of the high stratum in the study area is represented by 27 species distributed into 20 families (Table 3). Total abundance was 3 256 N ha-1 (Figure 3), with a coverage of 99.14 m2 ha-1. The abundance is similar to that of a conservation area (Yerena et al., 2014), which is higher than that existing in a silvopasture area (Patiño-Flores et al., 2021), but lower than that of a hunting ranch in the state of Coahuila, Mexico (Encina-Domínguez et al., 2020).

The family with the highest IVI was Fabacae, with 26.58 %. Its presence has been documented after anthropogenic activities, due to the tendency of the species to establish themselves in disturbed soils with low nutrient concentrations, as they can fix atmospheric N2 (Alanís-Rodríguez et al., 2018).

Vachellia rigidula (Fabaceae) was the most abundant species in the tree-shrub stratum, followed by Leucophyllum frutescens (Berland.) I. M. Johnst. (Scrophulariaceae) (Figure 3a). Both taxa are considered pioneers and have a high value of importance in subsequent assessments of different types of exploitation (Patiño-Flores et al., 2022). Furthermore, they are identified as part of the diet of white-tailed deer (Lozano-Cavazos et al., 2020), which contributes to the dispersal processes of these species.

The alpha diversity (2.63) and species richness (3.87) values for the high stratum are higher than those recorded for an UMA in the state of San Luis Potosi, where the white-tailed deer management is practiced (Dávila-Lara et al., 2019).

A total of 12 species were registered for the herbaceous stratum, with an abundance of 264 000 N ha-1 (Figure 3b) and a cover of 1 762.53 m2 ha-1. The Poaceae family accounted for 45.39 %, registering the highest importance value index; the taxa with the highest IVI value were Bouteloua gracilis (Kunth) Lag. ex Griffiths (24.42 %), and Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. (13.34 %). The dominance of these and other species classified as invasive in the herbaceous stratum (Carrillo et al., 2009) may be the product of a seed bank prevalent during the period of cattle ranching, an activity in which the use of fast-growing grasses is common (Jurado-Guerra et al., 2021).

Three strata were defined for the analysis of the vertical structure. In stratum I (high), 28 N ha-1 were recorded, only for Yucca filifera Chabaud; in stratum II (medium), there were 112 N ha-1 of the species Cercidium macrum I. M. Johnst., Cordia boissieri, Havardia pallens, Schaefferia cuneifolia A. Gray, and Vachellia rigidula, and in stratum III (low) all the species of the study were present, with a total of 4 084 N ha-1, the most abundant species being V. rigidula and B. gracilis. It is important to highlight that the height of Y. filifera affected the results of this index, as it was the only one present in stratum I.

The Pretzsch index yielded a result of Arel (68.91 %) which is related to a mean diversity, as values close to 100 % indicate an equitable distribution of species between the three strata (Pequeño et al., 2021). This value is lower than those indicated for a pasture with agroforestry use (Sarmiento-Muñoz et al., 2019) and for a temperate forest (Silva-García et al., 2021). This may be due to the fact that areas for agroforestry support not only grasslands but also tall woody species with a commercial value, while trees within a temperate forest are higher than those found in shrubland ecosystems (Vargas-Vázquez et al., 2022).

Finally, all species surviving in the reforestation, with the exception of Ebenopsis ebano and Diospyros texana, are present in the regeneration of vegetation, and, therefore, contribute diversity to the ecosystem (Patiño-Flores et al., 2022).

Conclusions

The present study provides valuable information on the current status of the MET in the process of recovery and undergoing reforestation to provide structure and species diversity. The diversity of naturally regenerated vegetation is higher than in some MET conservation areas and can be attributed to the coexistence of flora taxa at different stages of succession. Those species with a higher value of importance are characteristic of sites with a history of exploitation and are part of the diet of the white-tailed deer; therefore, game fauna would be contributing to their dispersal. The taxa that managed to become established have been cited with optimal growth at a standard planting density, under a closed tree-shrub canopy, and with a high dominance and cover of herbaceous species. In addition, several studies indicate the adaptation mechanisms that these taxa exhibit in the face of the climatic conditions of the region. Therefore, their use is recommended for future reforestation with native species under conditions similar to those of the study site.

The results provide useful information for decision-making in the monitoring and reforestation of MET communities, for which purpose it is of utmost importance to know and study the various successional stages of an ecosystem before intervening in it.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the IBERDROLA ENERGIA ESCOBEDO, S. A. DE C. V. company for all the facilities granted for the development of the present research, and to the Graduate School of Forest Sciences of the Autonomous University of Nuevo León, particularly to the Master's Program in Ecological Restoration, for the support provided.

REFERENCES

Alanís F., G. J., M. A. Alvarado V., L. Ramírez F., C. G. Velazco M. y R. Foroughbakhch P. 2011. Flora endémica de Nuevo León, México y estados colindantes. Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas 5(1):275-298. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41972517 . (17 de junio de 2021). [ Links ]

Alanís R., E., J. Jímenez P., M. A. González T., J. I. Yerena Y., G. Cuellar R. y A. Mora-Olivo. 2013. Análisis de la vegetación secundaria del matorral espinoso tamaulipeco, México. Phyton Revista Internacional de Botánica Experimental 82:185-191. http://www.revistaphyton.fund-romuloraggio.org.ar/vol82/ALANIS_RODRIGUEZ.pdf . (3 de septiembre de 2021). [ Links ]

Alanís R., E. , J. Jiménez P., P. A. Canizalez V., H. González R. y A. Mora-Olivo. 2015. Estado actual del conocimiento de la estructura arbórea y arbustiva del matorral espinoso tamaulipeco del noreste de México. Revista Iberoamericana de Ciencias 2(7):69-80. http://www.researchgate.net/publication/328729600_Estado_actual_del_conocimiento_de_la_estructura_arborea_y_arbustiva_del_matorral_espinoso_tamaulipeco_del_noreste_de_Mexico . (4 de abril de 2022). [ Links ]

Alanís-Rodríguez, E., A. Valdecantos-Dema, P. A. Canizales-Velázquez, A. Collantes-Chávez-Costa, E. Rubio-Camacho y A. Mora-Olivo. 2018. Análisis estructural de un área agroforestal en una porción del matorral xerófilo del noreste de México. Acta Botanica Mexicana 125:133-156. Doi: 10.21829/abm125.2018.1329. [ Links ]

Alanís-Rodríguez, E. , J. Jiménez-Pérez, A. Mora-Olivo, J. G. Martínez-Ávalos, … y E. A. Rubio-Camacho. 2015. Estructura y diversidad del matorral submontano contiguo al área metropolitana de Monterrey, Nuevo León, México. Acta Botanica Mexicana 113:1-19. Doi: 10.21829/abm113.2015.1093. [ Links ]

Alanís-Rodríguez, E. , V. M. Molina-Guerra, A. Collantes-Chávez-Costa, E. Buendía-Rodríguez, … and A. G. Alcalá-Rojas. 2021. Structure, composition and carbon stocks of woody plant community in assisted and unassisted ecological succession in a Tamaulipan thornscrub, Mexico. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural 94:1-12. Doi: 10.1186/s40693-021-00102-6. [ Links ]

Albrecht, C., Z. Contreras, K. Wahl-Villareal, M. Sternberg and B. O. Christoffersen. 2022. Winners and losers in dryland reforestation: species survival, growth, and recruitment along a 33-year planting chronosequence. Restoration Ecology The Journal of the Society for Ecological Restoration 30(4):e13559. Doi: 10.1111/rec.13559. [ Links ]

Bojórquez, A., A. Martínez-Yrízar and J. C. Álvarez-Yépiz. 2021. A landscape assessment of frost damage in the northmost Neotropical dry forest. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 308-309:108562. Doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2021.108562. [ Links ]

Cantú A., C., F. González S., P. Koleff O., J. Uvalle S., … y E. Ortíz H. 2011. El papel de las unidades de manejo ambiental en la conservación de los tipos de vegetación de Coahuila. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 2(6):113-123. Doi: 10.29298/rmcf.v2i6.578. [ Links ]

Carrillo S., S. M., T. Arredondo M., E. Huber-Sannwald y J. Flores R. 2009. Comparación en la germinación de semillas y crecimiento de plántulas entre gramíneas nativas y exóticas del pastizal semiárido. Técnica Pecuaria en México 47(3):299-312. https://repositorio.ipicyt.edu.mx/handle/11627/3656 . (20 de julio de 2022). [ Links ]

Clifford, H. T. and W. Stephenson. 1975. An Introduction to Numerical Classification. Academic Press. New York, NY, United States of America. 229 p. [ Links ]

ClimateData. 2023. Clima Cadereyta Jiménez, México. https://es.climate-data.org/america-del-norte/mexico/nuevo-leon/cadereyta-jimenez-58888/ . (23 de abril de 2023). [ Links ]

Colwell, R. K. 2023. EstimateS: Statistical estimation of species richness and shared species form samples Versión 9.1. Boulder, CO, United States of America. University of Colorado. https://www.robertkcolwell.org/pages/estimates . (18 de abril de 2023). [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional Forestal (Conafor). 2010. Prácticas de reforestación. Manual básico. Secretaría del Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Semarnat) y Conafor. Zapopan, Jal., México. 64 p. https://www.conafor.gob.mx/BIBLIOTECA/MANUAL_PRACTICAS_DE_REFORESTACION.PDF . (10 de julio de 2018). [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional Forestal (Conafor). 2015. Compensación Ambiental. Conafor. Zapopan, Jal., México. 5 p. https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/123875/Compensacion_Ambiental.pdf . (23 de abril del 2023). [ Links ]

Cuervo-Robayo, A. P., O. Téllez-Valdés, M. A. Gómez-Albores, C. S. Venegas-Barrera, J. Manjarrez y E. Martínez-Meyer. 2015a. Temperatura media anual en México (1910-2009). Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad. http://geoportal.conabio.gob.mx/metadatos/doc/html/tman13gw.html . (22 de enero de 2023). [ Links ]

Cuervo-Robayo, A. P. , O. Téllez-Valdés , M. A. Gómez-Albores , C. S. Venegas-Barrera, J. Manjarrez y E. Martínez-Meyer. 2015b. Precipitación anual en México (1910-2009). http://geoportal.conabio.gob.mx/metadatos/doc/html/preanu13gw.html . (22 de enero de 2023). [ Links ]

Curzel, V. y R. Hurtado. 2020. Daños por heladas en plantas frutales. Ministerio de Desarrollo Social Argentina, Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria y Ministerio de Agricultura, Ganadería y Pesca Argentina. Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, C, Argentina. 32 p. https://repositorio.inta.gob.ar/handle/20.500.12123/9286 . (23 de abril de 2023). [ Links ]

Dávila-Lara, M. A., Ó. A. Aguirre-Calderón, E. Jurado-Ybarra, E. Treviño-Garza, M. A. González-Tagle y G. Trincado. 2019. Estructura y diversidad de especies arbóreas en bosques templados de San Luis Potosí, México. Ecosistemas y Recursos Agropecuarios 6(18):399-409. Doi: 10.19136/era.a6n18.2112. [ Links ]

Domínguez G., T. G., R. G. Ramírez L., A. E. Estrada C., L. M. Scott M., H. González R. y M. del S. Alvarado. 2012. Importancia nutrimental en plantas forrajeras del matorral espinoso tamaulipeco. CIENCIA UANL 15(59):77-93. http://www.researchgate.net/publication/264041669_Importancia_nutrimental_en_plantas_forrajeras_del_matorral_espinoso_tamaulipeco . (30 de noviembre de 2021). [ Links ]

Encina-Domínguez, J. A., J. R. Arévalo-Sierra, J. A. Villarreal-Quintanilla y E. Estrada C. 2020. Composición, estructura y riqueza de plantas vasculares del matorral xerófilo en el norte de Coahuila, México. Botanical Sciences 98(1):1-15. Doi: 10.17129/botsci.2251. [ Links ]

Filio-Hernández, E., H. González-Rodríguez, T. G. Domínguez-Gómez, R. G. Ramírez-Lozano, I. Cantú-Silva and M. Del S. Alvarado. 2019. Seasonal water relations in four native plants from northeastern Mexico. Revista Bio Ciencias 6:e605. Doi: 10.15741/revbio.06.e605. [ Links ]

Foroughbakhch, R., J. L. Hernández-Piñero and A. Carrillo-Parra. 2014. Adaptability, growth and firewood volume yield of multipurpose tree species in semiarid regions of Northeastern Mexico. International Journal of Agricultural Policy and Research 2(12):444-453. Doi: 10.15739/IJAPR.016. [ Links ]

Gallina-Tessaro, S. A., A. Hernández-Huerta, C. A. Delfín-Alfonso y A. González-Gallina. 2009. Unidades para la conservación, manejo y aprovechamiento sustentable de la vida silvestre en México (UMA). Retos para su correcto funcionamiento. Investigación Ambiental 1(2):143-152. https://biblat.unam.mx/es/revista/investigacion-ambiental-ciencia-y-politica-publica/articulo/unidades-para-la-conservacion-manejo-y-aprovechamiento-sustentable-de-la-vida-silvestre-en-mexico-uma-retos-para-su-correcto-funcionamiento . (23 de marzo de 2022). [ Links ]

García, E. 2004. Modificaciones al sistema de clasificación climática de Köppen (para adaptarlo a las condiciones de la República Mexicoana). Instituto de Geografía de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Coyoacán, México D. F., México. 90 p. http://www.publicaciones.igg.unam.mx/index.php/ig/catalog/view/83/82/251-1 . (22 de enero de 2023). [ Links ]

García, J. F. 2011. Can environmental variation affect seedling survival of plants in northeastern Mexico? Archives of Biological Sciences 63(3):731-737. Doi: 10.2298/ABS1103731G. [ Links ]

González R., H., I. Cantú S., M. V. Gómez M. and R. G. Ramírez L. 2004. Plant water relations of thornscrub shrub species, north-eastern Mexico. Journal of Arid Environments 58(4):483-503. Doi: 10.1016/j.jaridenv.2003.12.001. [ Links ]

González R., H. , R. Maiti and A. Kumari C. 2017a. Comparative anatomy of leaf lamina of twenty six woody species of Tamaulipan thornscrub from northeastern Mexico and its significance in taxonomic delimitation and adaptation of the species to xeric environments. Pakistan Journal of Botany 49(2):589-596. https://www.pakbs.org/pjbot/PDFs/49(2)/27.pdf . (3 de mayo de 2021). [ Links ]

González R., H. , R. Maiti and A. Kumari. 2017b. Seasonal variation in specific leaf area, epicuticular wax and pigments in 15 woody species from northeastern Mexico during summer and winter. Pakistan Journal of Botany 49(3):1023-1031. http://www.pakbs.org/pjbot/papers/1497350316.pdf . (2 de abril de 2021). [ Links ]

González-Oreja, J. A., A. A. de la Fuente-Díaz-Ordaz, L. Hernández-Santín, D. Buzo-Franco y C. Bonache-Regidor. 2010. Evaluación de estimadores no paramétricos de la riqueza de especies. Un ejemplo con aves en áreas verdes de la ciudad de Puebla, México. Animal Biodiversity and Conservation 33:31-45. Doi: 10.32800/abc.2010.33.0031. [ Links ]

González-Saldívar, F., J. Uvalle-Sauceda, C. Cantú-Ayala, L. Reséndiz-Dávila, D. González-Uribe y C. A. Olguín-Hernández. 2014. Efecto de la precipitación sobre la productividad del matorral espinoso tamaulipeco disponible para Odocoileus virginianus. Agroproductividad 7(5):3-8. https://revista-agroproductividad.org/index.php/agroproductividad/article/view/548 . (28 de octubre de 2022). [ Links ]

Gutiérrez-Barrientos, M., J. D. Marín-Solís, E. Alanís-Rodríguez y E. Buendía-Rodríguez . 2022. Evaluación de una restauración mediante dron en el matorral espinoso tamaulipeco. Polibotánica 54(27):71-85. Doi: 10.18387/polibotanica.54.5. [ Links ]

Hortal, J., P. A. V. Borges and C. Gaspar. 2006. Evaluating the performance of species richness estimators: sensitivity to sample grain size. Journal of Animal Ecology 75(1):274-287. Doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2006.01048.x. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI). 2013. Ciudad Río Bravo G14-8, Carta Edafológica Serie II, Escala 1:25 000. INEGI. https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/productos/prod_serv/contenidos/espanol/bvinegi/productos/geografia/tematicas/Edafologia_hist/1_250_000/702825236199.pdf . (11 de julio de 2022). [ Links ]

Johnson, D. M., J-C. Domec, Z. Carter B., A. M. Schwantes, … and R. B. Jackson. 2018. Co-occurring woody species have diverse hydraulic strategies and mortality rates during an extreme drought. Plant, Cell & Environment 41(3):576-588. Doi: 10.1111/pce.13121. [ Links ]

Jurado, E., J. F. García, J. Flores and E. Estrada. 2006. Leguminous seedling establishment in Tamaulipan thornscrub of northeastern Mexico. Forest Ecology and Management 221(1-3):133-139. Doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2005.09.011. [ Links ]

Jurado-Guerra, P., M. Velázquez-Martínez, R. A. Sánchez-Gutiérrez, A. Álvarez-Holguín, … y M. G. Chávez-Ruiz. 2021. Los pastizales y matorrales de zonas áridas y semiáridas de México: Estatus actual, retos y perspectivas. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Pecuarias 12(3):261-285. Doi: 10.22319/rmcp.v12s3.5875. [ Links ]

Leal-Elizondo, N. A., E. Alanís-Rodríguez , J. M. Mata-Balderas, E. J. Treviño-Garza y J. I. Yerena-Yamallel. 2018. Estructura y diversidad de especies leñosas del matorral espinoso tamaulipeco regenerado postganadería en el noreste de México. Polibotánica 45(23):75-88. https://polibotanica.mx/index.php/polibotanica/article/view/220 . (24 de abril de 2023). [ Links ]

Lonard, R. I. and F. W. Judd. 1991. Comparison of the effects of the severe freezes of 1983 and 1989 on native woody plants in the lower Rio Grande Valley, Texas. The Southwestern Naturalist 36(2):213-217. Doi: 10.2307/3671923. [ Links ]

López A., R. y M. López G. 2013. Evaluación y comportamiento paisajístico de especies nativas en Linares, N. L., 16 años de evaluación. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 4 (17):164-173. Doi: 10.29298/rmcf.v4i17.429. [ Links ]

López L., Á. y M. Pando M. (Coords.). 2014. Región Citrícola de Nuevo León. Su complejidad territorial en el marco global. Instituto de Geografía de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México y Facultad de Ciencias Forestales de la Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. Coyoacán, México D. F., México. 382 p. [ Links ]

Lozano-Cavazos, E. A., F. I. Gastelum-Mendoza, L. Reséndiz-Dávila , G. Romero-Figueroa, F. N. González-Saldívar and J. I. Uvalle-Sauceda. 2020. Diet composition of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus texanus Mearns) identified in ruminal content in Coahuila, Mexico. Agroproductividad 13(6):49-54. Doi: 10.32854/agrop.vi.1702. [ Links ]

Maiti, R., H. Gonzalez R., A. Kumari and N. C. Sarkar. 2016. Research advances on experimental biology of woody plants of a Tamaulipan thorn scrub, northeastern Mexico and research needs. International Journal of Bio-resource and Stress Management 7(5):1197-1205. Doi: 10.23910/IJBSM/2016.7.5.1632a. [ Links ]

Maldonado-Benitez, K. R., A. Aldrete, J. López-Upton, H. Vaquera-Huerta y V. M. Cetina-Alcalá. 2011. Producción de Pinus greggii Engelm. en mezclas de sustrato con hidrogel y riego, en vivero. Agrociencia 45(3):389-398. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=30219764011 . (21 de junio del 2023). [ Links ]

Marroquín-Castillo, J. J., E. Alanís-Rodríguez , J. Jiménez-Pérez, O. A. Aguirre-Calderón, … y A. Collantes-Chávez-Costa . 2017. Efecto de la restauración post-minería de la comunidad vegetal del matorral xerófilo, en Nuevo León, México. Acta Botanica Mexicana (120):7-20. Doi: 10.21829/abm120.2017.1262. [ Links ]

Martín C., B. del R., M. Vanoye E., H. A. Dzib R., G. Avilés R. y J. A. Alavez G. 2022. Sobrevivencia de plantas nativas forestales para la reforestación en áreas perturbadas por actividades agropecuarias en el ejido de Arellano, Champotón, Campeche, México. Ciencia Latina Revista Multidisciplinar 6(6):11041-11059. Doi: 10.37811/cl_rcm.v6i6.4184. [ Links ]

Mata B., J. M., K. A. Cavada P., T. I. Sarmiento M. y H. González R. 2022. Monitoreo de la supervivencia de una reforestación con especies nativas del matorral espinoso tamaulipeco. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 13(71):28-52. Doi: 10.29298/rmcf.v13i71.1229. [ Links ]

Meteored. 2023. Histórico del clima en Guadalupe. https://www.meteored.mx/guadalupe/historico . (24 de abril de 2023). [ Links ]

Molina-Guerra, V. M., A. Mora-Olivo, E. Alanís-Rodríguez , B. E. Soto-Mata y A. M. Patiño-Flores. 2019. Plantas características del matorral espinoso tamaulipeco en México. Universitaria de la Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. Monterrey, NL, México. 114 p. [ Links ]

Molina-Guerra, V. M. , E. Alanís-Rodríguez , A. Collantes-Chávez-Costa , A. Mora-Olivo, E. Buendía-Rodríguez y E. de la Rosa-Manzano. 2023. Restauración de un fragmento de matorral espinoso tamaulipeco: respuesta de ocho especies leñosas. Colombia Forestal 26(1):36-47. Doi: 10.14483/2256201X.19056. [ Links ]

Mora D., C. A., E. Alanís R., J. Jiménez P., M. A. González T ., J. I. Yerena Y. y L. G. Cuellar R. 2013. Estructura, composición florística y diversidad del matorral espinoso tamaulipeco, México. Ecología Aplicada 12(1):29-34. Doi: 10.21704/rea.v12i1-2.435. [ Links ]

Mueller-Dombois, D. and H. Ellenberg. 1974. Aims and methods of vegetation ecology. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. New York, NY, United States of America. 547 p. [ Links ]

Patiño-Flores, A. M., E. Alanís-Rodríguez , E. Jurado, H. González-Rodríguez , O. A. Aguirre-Calderón y V. M. Molina-Guerra . 2021. Estructura y diversidad del matorral espinoso tamaulipeco regenerado posterior a uso pecuario. Polibotánica 52(26):75-88. Doi: 10.18387/polibotanica.52.6. [ Links ]

Patiño-Flores, A. M. , E. Alanís-Rodríguez , V. M. Molina-Guerra , E. Jurado , … y A. Collantes-Chávez-Costa . 2022. Regeneración natural en un área restaurada del matorral espinoso tamaulipeco del Noreste de México. Ecosistemas y Recursos Agropecuarios 9(1):e2853. Doi: 10.19136/era.a9n1.2853. [ Links ]

Pequeño L., M. Á., E. Alanís R., V. M. Molina G., A. Collantes-Chávez-Costa and A. Mora-Olivo. 2021. Structure and diversity of a shrub Helietta parvifolia (A. Gray ex Hemsl.) Benth. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 12(63):88-113. Doi: 10.29298/rmcf.v12i63.762. [ Links ]

Pequeño-Ledezma, M. Á., E. Alanís-Rodríguez , J. Jiménez-Pérez, O. A. Aguirre-Calderón, M. A. González-Tagle y V. M. Molina-Guerra . 2017. Análisis estructural de dos áreas del matorral espinoso tamaulipeco del noreste de México. Madera y Bosques 23(1):121-132. Doi: 10.21829/myb.2017.2311125. [ Links ]

Pontifes, P. A., P. M. García-Meneses, L. Gómez-Aíza, A. I. Monterroso-Rivas and M. Caso-Chávez. 2018. Land use/land cover change and extreme climatic events in the arid and semi-arid ecoregions of Mexico. Atmósfera 31(4):355-372. Doi: 10.20937/atm.2018.31.04.04. [ Links ]

Pretzsch, H. 2009. Forest Dynamics, Growth and Yield. From Measurement to Model. Springer-Verlag. Heidelberg, BW, Germany. 664 p. [ Links ]

Qin, J., Z. Shangguan and W. Xi. 2018. Seasonal variations of leaf traits and drought adaptation strategies of four common woody species in South Texas, USA. Journal of Forestry Research 30(3):1-11. Doi: 10.1007/s11676-018-0742-2. [ Links ]

Ramírez D., M. 2011. Metodología para realizar y presentar los Informes de Supervivencia Inicial (ISI) de las plantaciones forestales comerciales (Aspectos técnicos). Comisión Nacional Forestal (Conafor), ProÁrbol y Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Semarnat). Zapopan, Jal., México. 19 p. http://www.conafor.gob.mx:8080/documentos/ver.aspx?grupo=6&articulo=1564 . (03 de junio de 2021). [ Links ]

Rodríguez-Rojas, J. J., Á. Rodríguez-Moreno, M. Berzunza-Cruz, G. Gutiérrez-Granados, … and E. A. Rebollar-Téllez. 2017. Ecology of phlebotomine sandflies and putative reservoir hosts of leishmaniasis in a border area in Northeastern Mexico: implications for the risk of transmission of Leishmania mexicana in Mexico and the USA. Parasite 24:1-17. Doi: 10.1051/parasite/2017034. [ Links ]

Sarmiento-Muñoz, T. I., E. Alanís-Rodríguez , J. M. Mata-Balderas y A. Mora-Olivo. 2019. Estructura y diversidad de la vegetación leñosa en un área de matorral espinoso tamaulipeco con actividad pecuaria en Nuevo León, México. CienciaUAT 14(1):31-44. Doi: 10.29059/cienciauat.v14i1.1001. [ Links ]

Schlegel, B., J. Gayoso y J. Guerra. 2001. Manual de procedimientos para inventarios de carbono en ecosistemas forestales. Universidad Austral de Chile. Valdivia, ZAL, Chile. 15 p. https://www.ccmss.org.mx/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Manual_de_procedimiento_para_inventarios_de_carbono_en_ecosistemas_forestales.pdf . (3 de junio de 2021). [ Links ]

Serna-Lagunes, R., A. Olguín-Hernández, J. A. Pérez-Sato, C. G. García-García, I. Casas-López y J. Salazar-Ortíz. 2013. Venado Veracruzano (Odocoileus virginianus veraecrucis): Una opción para la ganadería diversificada y la conservación de ecosistemas. Agroproductividad 6(5):58-64. https://revista-agroproductividad.org/index.php/agroproductividad/article/view/485 . (23 de abril del 2023). [ Links ]

Servicio Meteorológico Nacional (SMN). 2023. Normales Climatológica por Estado. https://smn.conagua.gob.mx/es/informacion-climatologica-por-estado?estado=nl . (21 de abril del 2023). [ Links ]

Shannon, C. E. and W. Weaver. 1949. The Mathematical Theory of Communication. University of Illinois Press. Illinois, IL, United States of America. 117 p. [ Links ]

Silva-García, J. E., O. A. Aguirre-Calderón, E. Alanís-Rodríguez, E. Jurado-Ybarra, J. Jiménez-Pérez y B. Vargas-Larreta. 2021. Estructura y diversidad de especies arbóreas en un bosque templado del noroeste de México. Polibotánica 52:89-102. Doi: 10.18387/polibotanica.52.7. [ Links ]

Vargas-Vázquez, V. A., N. I. Sánchez-Rangel, C. J. Vázquez-Reyes, J. G. Martínez-Ávalos and A. Mora-Olivo. 2022. Composition and structure of a low semi-thorn shrubland in Northeastern Mexico. Botanical Sciences 100(3):748-758. Doi: 10.17129/botsci.2970. [ Links ]

Vega-López, J. A., E. Alanís-Rodríguez , V. M. Molina-Guerra , E. Buendía-Rodríguez , J. D. Marín-Solís y A. G. Alcalá-Rojas . 2017. Selección de especies arbóreas y arbustivas para la restauración del matorral espinoso tamaulipeco. Árido-Ciencia 2(1):3-10. http://fcbujed.com/aridociencia/numeros/2017/VIIN2/articulo1.pdf . (21 de abril del 2023). [ Links ]

Venegas L., M. 2016. Manual de mejores prácticas de restauración de ecosistemas degradados, utilizando para reforestación solo especies nativas en zonas prioritarias. Comisión Nacional Forestal, Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, Global Environment Facility y Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo. Zapopan, Jal., México. 160 p. https://www.biodiversidad.gob.mx/media/1/especies/Invasoras/files/comp1/Manual_reforestacion_utilizando_especies_nativas.pdf . (14 de marzo de 2022). [ Links ]

Villarreal G., J. G. 2014. Veinte años de la repoblación de venado cola blanca texano en Cerralvo, Nuevo León, México. CIENCIA UANL 17(67):63-68. https://cienciauanl.uanl.mx/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/repoblarvenado1767.pdf . (7 de julio de 2022). [ Links ]

Whittaker, R. H. 1972. Evolution and measurement of species diversity. Taxon The Journal of the International Association for Plant Taxonomy 21(2-3):213-251. Doi: 10.2307/1218190. [ Links ]

Willott, S. J. 2001. Species accumulation curves and the measure of sampling effort. Journal of Applied Ecology 38(2):484-486. Doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2664.2001.00589.x. [ Links ]

Yang L. and M. Liu. 2023. 2021 February Texas ice storm induced spring GPP reduction compensated by the higher precipitation. Earth's Future (11):1-13. Doi: 10.1029/2022EF003030. [ Links ]

Yerena Y., J. I., J. Jiménez P., E. Alanís R., O. A. Aguirre C., M. A. González T. y E. J. Treviño G. 2014. Dinámica de la captura de carbono en pastizales abandonados del noreste de México. Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems 17:113-121. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/939/93930735009.pdf . (19 de noviembre de 2022). [ Links ]

Received: February 27, 2023; Accepted: June 20, 2023

texto en

texto en