Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

versión impresa ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.11 no.59 México may./jun. 2020 Epub 15-Jul-2020

https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v11i59.700

Scientific article

Phenotype selection and reproductive characteristics of Pinus pseudostrobus var. oaxacana (Mirov) S.G.Harrison

1Instituto Tecnológico del Valle de Oaxaca. México.

2Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus Montecillo. México.

3Campo Experimental Valles Centrales, CIR-Pacífico Sur, INIFAP. México.

Pinus pseudostrobus var. oaxacana, an important species of Oaxaca State from its wood quality; even though it is preferred for reforestation and plantations, the seed production capacity of this species is unknown. The aim of the actual study was to evaluate the morphological variation, reproductive characteristics and their relationship with environmental factors of cones and seeds of selected P. pseudostrobus var. oaxacana trees as seed trees from five provenances of the state. From November to December 2017, 1 058 cones were collected from 42 selected trees, to which the following characteristics were assessed: length, diameter, dry weight, number of scales, number and of weight of fully developed seeds, average weight per seed, reproductive efficiency and inbreeding index. Trees and provenances were differentiated by analysis of variance and mean tests (Duncan, 0.05). Reproductive characteristics were correlated with environmental variables (collection sites) and morphological characteristics. Selected trees were 51.7±8.0 years old, 36.4±4.6 m high and 54.5±8.2 cm diameter at breast height. The average values per cone were: 101.3 mm long; 56 mm diameter, 97.9 g dry weight; 133 scales; 107 developed seeds per cone; 2.35 g weight of developed seeds per cone; 0.021 g average weight per seed; reproductive efficiency of 13.09 mg per gram of strobilus; inbreeding index (II = 0.50) indicates a high level of self-fertilization. Of the evaluated characteristics, reproductive efficiency and II did not show significant differences.

Key words Outstanding tree; seed tree; cones characteristics; reproductive characteristics; inbreeding; environmental factors

Pinus pseudostrobus var. oaxacana es un taxon importante en Oaxaca por la calidad de su madera; aunque, también es preferida para la reforestación y plantaciones, pero se desconoce su capacidad para la producción de semilla. Los objetivos de la presente investigación consistieron en evaluar la variación morfológica, conocer las características reproductivas de conos y semillas y su relación con factores ambientales de árboles semilleros de la especie de interés seleccionados en cinco procedencias del estado. Durante noviembre y diciembre de 2017, se recolectaron 1 058 conos de 42 individuos a los que se les midieron variables morfológicas, y determinaron la eficiencia reproductiva e índice de endogamia; los árboles y procedencias se diferenciaron mediante análisis de varianza y pruebas de medias de Duncan. Las características reproductivas se correlacionaron con variables ambientales (sitios de recolecta) y dasométricas de los progenitores. Los datos registrados fueron 51.7±8.0 años de edad, altura de 36.4±4.6 m y diámetro normal de 54.5±8.2 cm. Los valores medios obtenidos por cono fueron: longitud 101.3 mm, diámetro 56 mm, peso seco 97.9 g, 133 escamas, 107 semillas desarrolladas por cono; las semillas desarrolladas por cono pesaron 2.35 g, peso promedio por semilla 0.021 g; eficiencia reproductiva 13.09 mg por gramo de estróbilo; IE = 0.50 (índice de endogamia), que indica un alto nivel de autofecundación; el IE decrece con la altitud y aumenta con la cantidad de recolecta. De las características evaluadas, la eficiencia reproductiva e IE no mostraron diferencias significativas entre poblaciones.

Palabras clave Árbol sobresaliente; árbol semillero; características de conos; características reproductivas; endogamia; factor ambiental

Introduction

Pinus pseudostrobus var. oaxacana (Mirov) S.G.Harrison is an economically important conifer in Mexico from its timber; it has a relatively fast growth, good stem shape and excellent wood quality (López-Upton, 2002), which makes it very suitable for commercial plantations and reforestation in southern Mexico (Viveros et al., 2005). Currently, there is interest in conserving and increasing the areas with this species, which has favored a great demand for phenotypic and genetic quality seedlings for reforestation (Semarnat, 2016). Every year seedlings are produced for this purpose (Domínguez et al., 2016); however, seed collection comes from natural stands in seed years, and there is no record of the characteristics of the parent trees. Therefore, not always the quality of the plants obtained can be assured as well as their survival probabilities at the site of their final establishment. Many times the seeds quality of the seeds is also affected, which includes their physical characteristics, the percentage of empty seeds, the percentage of viability and, consequently, the percentage of germination and germination energy (Bustamante-García et al., 2012).

In this scenario, it is necessary to carry out tree improvement programs that, combined with proper management of propagation procedures in the nursery, support plantations and reforestation, in addition to increasing the survival, productivity and wood quality in future generations (Salaya-Domínguez et al., 2012). To achieve the above, since 2017 the establishment of an asexual seed orchard in Oaxaca state is being carried out by the Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP) (National Institute for Forestry, Agriculture and Livestock Research) sponsored by the Conacyt-Conafor sector fund, in which individuals have already been chosen (Leyva-Ovalle and Vargas-Hernández, 2018).

The trees selected in different populations may show variation in the degree of expression of various characteristics from the site quality; this represents the response in the development of a certain tree species to all the environmental conditions (edaphic, climatic and biotic) existing in a particular place (Kimmins, 2004). Thus, the selection of trees through an altitudinal gradient and different environments can show patterns of differential genetic variation; however, in Oaxaca little is known about this type of distribution in P. pseudostrobus var. oaxacana, which limits the creation of guidelines for the movement of seeds and seedlings for reforestation and their adaptation to climate change (Castellanos et al., 2013).

In this context, the climate change scenarios indicate that in Mexico by 2030 there will be an increase in the average annual temperature (compared to the 1961-1990 average) of 1.5 °C and a 7 % decrease in precipitation (Sáenz-Romero et al., 2010). A temperature increase will favor the expansion of forests in high latitudes, while in mid latitudes a decrease or migration of populations to areas with climates more suitable for their development is expected (Sáenz et al., 2011). Climate change represents, then, an additional challenge to couple genotypes to environments, starting from the fact that the variation in the morphology of cones and seeds may be determined, mainly, by genotypic characteristics, with the restriction imposed by the environment (Krannitz and Duralia, 2004); The relative proportion of these two factors in their contribution to phenotypic variation at the population, species level and even between individuals, is unknown (Ramírez-Sánchez et al., 2011).

The proper use of forest germplasm needs knowledge of the morphological characteristics of cones and seeds of the selected trees (Quiroz-Vásquez et al., 2017); also of the potential and efficiency of seed production to estimate the quantity and quality of germplasm (Sáenz-Romero et al., 2012); however, in Oaxaca the seed production capacity of the natural forests of P. pseudostrobus var. oaxacana is still unknown.

The objective of the present work was to evaluate the morphological variation and the reproductive characteristics of cones and seeds of trees of P. pseudostrobus var. oaxacana selected as seed producers, as well as correlating these characteristics with climatic variables of the collection sites and tree-mensuration characteristics of phenotypes of different populations in the state of Oaxaca.

Materials and Methods

Phenotypically plus tree selection and seed collection areas

During November and December 2017, 42 phenotypically plus trees were selected in stands of P. pseudostrobus var. oaxacana of Santa Catarina Ixtepeji, Teococuilco de Marcos Pérez, Santa María Jaltianguis and San Pedro Yolox municipalities in the Sierra Norte of Oaxaca State using the comparison or control tree methodology (Bramlett et al., 1977) in which the characteristics of an outstanding or plus candidate tree is compared to the best five neighboring trees within a population, with a minimum distance of 25 m and maximum of 50 m. The candidate and control trees were in the reproductive age (51.7 ± 8.0 years), came from the dominant stratum, with a straight stem, not forked or twisted, round crown, insertion of branches at 90° to the stem, crown size 1/3 of the total height of the tree, diameter at breast height (54.5 ± 8.2 cm), height (36.4 ± 4.6 m), total volume (3.8 ± 1.4 m3) and height of clean stem (21.8 ± 4.6 m) higher than the average of control and healthy trees, free of pests and diseases, obtained with a Pressler's drill) (Muñoz-Flores et al., 2013) (Table 1). The heights were measured with a clinometer (Suunto, modelo PM5/1520) and the diameters with a diameter tape (Forestry Suppliers Inc., modelo 283D/20F).

Table 1 Pinus pseudostrobus var. oaxacana (Mirov) S.G.Harrison outstanding phenotypical characteristics.

| Variable | Ixtepeji | Ixtlán | Jaltianguis | Teococuilco | Yolox |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height (m) | 37.4±0.2 | 39.5±2.5 | 34.8±0.2 | 35.7±0.3 | 40.0±0.3 |

| AFL (m) | 23.6±0.2 | 26.0±0.0 | 18.3±0.2 | 21.8±0.3 | 24.5±0.5 |

| Normal diameter (cm) | 58.3±0.4 | 58.3±3.8 | 52.9±0.5 | 51.2±0.3 | 54.9±0.7 |

| Age (years) | 55.4±0.2 | 53.5±5.5 | 50.0±0.7 | 49.6±0.4 | 47.5±0.3 |

| Crown area (m2) | 53.6±0.3 | - | 58.2±0.4 | 56.4±0.3 | 59.2±0.8 |

| Basimetric area (m2) | 0.3±0.0 | 0.3±0.0 | 0.2±0.0 | 0.2±0.0 | 0.2±0.0 |

| Total volume (m3)¶ | 4.5±0.1 | 4.6±0.8 | 3.5±0.1 | 3.3±0.1 | 4.1±0.1 |

| Commercial volume (m3) | 4.3±0.1 | 4.5±0.8 | 3.3±0.1 | 3.2±0.1 | 4.0±0.1 |

| DB (kg m-3) | 506.5±3.0 | 528.8±12.9 | 489.2±3.1 | 493.7±1.9 | 477.5±0.6 |

Source: Sistema biométrico de Oaxaca (Corral-Rivas and Vargas-Larreta, 2013).

AFL = Clean stem height; DB = Wood basic density. The mean standard error is included.

The crown dominance index as a measure of pollen availability for neighboring specimens of the tree selected as superior, was calculated by subtracting the candidate's height minus the average height of the controls; the site quality index was obtained from the quotient between the average height and the average age of the tree selected as plus and its controls; and the site productivity index of the quotient between the average volume and the average age of the tree selected as superior and its controls (Vallejos et al., 2010).

A total of 1 058 cones were collected from the selected trees, which were identified and transferred to the INIFAP forest greenhouse in Valles Centrales de Oaxaca to be analyzed during the 2018-2019 period. The cones were separated by a select tree (42) in identified raffia bags, where they remained between 2 and 3 days; finally the cones were dissected to release the seed, which was stored for 2 to 3 months in paper bags.

Cone and seed analysis

The analysis of the cones was based on the methodology of Bramlett et al. (1977) and Mosseler et al. (2000) with modifications according to the study. The indicators or reproductive characteristics that were analyzed were: green weight (PVC, g) of each cone determined by means of an analytical balance with a 200 g ± 0.1 mg capacity (Shimadzu modelo ATY224); length (LC, mm) and cone diameter (DC, mm) were measured with a digital ± 0.2 mm caliper (Titan® Classic). Afterwards, all the cones separated by tree were exposed to solar radiation in the greenhouse for two to three weeks to favor the opening of scales and extraction of seeds. The dry weight of each cone (PSC, g) was recorded after the opening of the scales at room temperature, two to three weeks after collection. The total number of scales per cone (NE) was counted, the number of seeds developed per cone (NSDC) corresponded to mature seeds (including empty and full); and the weight of the seeds developed by cone (PSDC, g) was determined. With these data, the following relationships were calculated:

Where:

CH = Moisture content (%)

PVC = Green weight of the cone (g)

PSC = Dry weight of the cone (g)

CF = Cone shape coefficient, cone diameter (DC, mm), cone length (LC, mm)

EPSD = Fully-grown seed production efficiency

PSDC = Fully-grown seed weight/cone

PPS = Average weight per seed

NSDC = Number of fully-grown seeds per cone

PEE = Scale efficiency percentage

NE = Total number of scales per cone (as a measurement of effective scales for seed production)

In order to determine the amount of full and empty seeds and thus, to obtain the reproductive efficiency and inbreeding index per cone and tree (Bramlett et al., 1977), The cone and seed variables were taken from a sample of 50 cones.

Afterwards, five reproductive indicators proposed by Mosseler et al. (2000) were calculated: 1) total weight of cones on the tree (PCA, g) sum of dry weight of cones; 2) number of full-grown seeds per tree seeds (NSDA); and:

Where:

PSDA (g) = Sum of the fully-grown seed weights in the total number of cones

ER (g) = Reproductive efficiency, as a measurement of the energy rate used in the reproductive effort stored in the seed.

IE = Inbreeding index

SV = Empty seeds

SL = Full seeds

Climatic variables

In order to obtain physiographic and climatic variables of the sites of origin of the collected material, the geographic location coordinates of the trees selected as superior were entered on the WorldClim website: Research on climate change in forests: potential effects of Global warming in forests and the relationships between plant climate in western North America and Mexico (WorldClim, 2019).

Data management and analysis

By means of the general linearized model, the trees, their provenances and sub-provenances were differentiated and the were established according to the geographical location of the trees. Ln(x) and square root transformations were performed to reproductive variables of the specimens selected as plus trees for compliance with the normality and homogeneity of the variances.

The model used was:

Where:

Y ijk = Value of the dependent variable

( = Population mean

R i = Effect of the i-th geográfic region

P j (R i ) = Provenance or collection location nested in region

A k (P j ) = Tree nested in provenance

ε ijk = Experimental error

The variance components associated with each source of variation (indicated in the model) and their contribution to the total variance were estimated by the VARCOMP procedure, REML option; progenies and provenances were separated by GLM with the Duncan test (( = 0.05); and for the associations between the morphological variables and the reproductive characteristics with climatic variables, a Pearson correlation analysis and the differences estimated with Duncan (SAS®) were made (SAS, 2004).

Results and Discussion

Reproductive characteristics of cones and seeds

The analysis of variance shows that the four regions, as well as the interactions provenance × region and tree × provenance had highly significant differences (p ≤ 0.01) in the reproductive characteristics of cones and seeds (Table 2). In other Pinus species such as P. leiophylla Schltdl. & Cham. (Gómez et al., 2010), P. engelmanni Carr. (Bustamante-García et al., 2012), P. greggii Engelm. ex Parl. (Rodríguez et al., 2012) and P. patula Schiede ex Schltdl. & Cham. (Salaya-Domínguez et al., 2012) there have been differences between sites and between trees for the features of these structures, indicating that they are influenced by the environment and that there is probably also genetic differentiation between populations, not being possible to separate the environmental effect from the genetic one (Viveros et al., 2013).

Table 2 Summary of analysis of variance for cone and seed variables of selected Pinus pseudostrobus var. oaxacana (Mirov) S.G.Harrison trees from Oaxaca.

| Source of variation | Variable | R | P(R) | A(P) | Error | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degrees of freedom | 3 | 5 | 33 | 1 016 | 1 057 | |

| Mean squares and significance | LC | 1 312.4** | 5 007.1** | 3 428.7** | ||

| DC | 1 465.1** | 726.4** | 562** | |||

| CF | 0.04** | 0.07** | 0.06** | |||

| PV | 50 608.6** | 52 094.5** | 46 249.7** | |||

| PS | 71 635.4** | 25 594.3** | 19 807.2** | |||

| CH | 4.7** | 0.3** | 0.7** | |||

| NE | 3 240.4** | 785.7** | 4 133.9** | |||

| NSD | 33 028.5** | 30 508.7** | 36 361** | |||

| PSD | 31.7** | 24.5** | 29.1** | |||

| PPS | 28.1** | 120.9** | 69** | |||

| PEE | 2** | 1.5** | 1.6** |

R = Region; P(R) = Provenance nested in region; A(P) = Selected tree nested in region; LC = Cone length; DC = Cone diameter; CF = Cone shape coefficient; PV = Green weight of the cone; PS = Dry weight of the cone; CH = Moisture content; NE = Total number of scales; NSD = Number of fully-grown seeds; PSD = Fully-grown seed weight; PPS = Average weight per seed; PEE = Scale efficiency percentage.**p ≤ 0.01.

The cones collected in the Yolox provenance had higher values than the general average of the collection in eight variables: length (105.6 mm), diameter (59.2 mm), dry weight (140.9 g), number of scales (138), number of fully-grownseeds (132), weight of fully-grown seeds (3.2 g), average weight per seed (0.024 g) and percentage of scale effectiveness (48 %) (Table 3). The moisture content was lower than the average (19 %), perhaps because when the cones were collected, they showed a greater degree of maturity compared to those from the other three communities. Those from Jaltianguis had the highest averages in shape coefficient (0.57) and green weight (169.3 g), lower average in the number of seeds developed (97) and percentage of scale effectiveness (34 %).

Table 3 Variance components for the characteristics of cones and seeds of the Pinus pseudostrobus var. oaxacana (Mirov) S.G.Harrison plus trees.

| Variables | General Mean | Total Variance | Region (%) | Provenence (Region, %) | Tree (Provenance, %) | Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC (mm) | 101.3 | 224.6 | 0** | 0** | 61** | 39.0 |

| DC (mm) | 56 | 46.3 | 10** | 0.9** | 57.1** | 32.0 |

| CF | 0.55 | 0.003 | 0** | 0** | 66** | 34.0 |

| PV (g) | 155 | 3 034.9 | 3** | 0** | 70** | 27.0 |

| PS (g) | 97.9 | 1 953.8 | 30** | 0** | 50** | 20.0 |

| CH (%) | 62 | 0.094 | 33** | 0** | 33** | 34.0 |

| NE | 133.7 | 471 | 1.6** | 0** | 34.2** | 64.2 |

| NSD | 107 | 2 420.6 | 0** | 0** | 67** | 33.0 |

| PSD (g) | 2.3 | 1.94 | 0** | 0** | 70** | 30.0 |

| PPS (g) | 0.02 | 0.000029 | 0** | 0** | 69** | 31.0 |

| PEE | 0.40 | 0.03 | 1.3** | 0** | 56** | 42.7 |

LC = Cone length; DC = Cone diameter; CF = Cone shape coefficient; PV = Green weight of the cone; PS = Dry weight of the cone; CH = Moisture content; NE = Total number of scales; NSD = Number of fully-grown seeds; PSD = Fully-grown seed weight; PPS = Average weight per seed; PEE = Scale efficiency percentage.

The cones collected in Ixtepeji recorded the lowest averages in eight of 11 evaluated characteristics: length (99.05 mm), diameter (53.5 mm), dry weight (85.2 g), green weight (140.2 g), number of scales (130), shape coefficient (0.54), fully-grown seed weight (2.1 g) and average weight per seed (0.020 g), except in moisture content (0.66 %), which was higher than the general collection average (Table 3).

The length and diameter of the cone for the four provenances are in the range reported in the same species (Márquez, 2007; Espinoza et al., 2009; Sáenz-Romero et al., 2011; Domínguez et al., 2016); on the contrary, they are higher than the average values, for length (79.8 mm) and diameter (38 mm) determined by Espinoza et al. (2009). The number of fully-grown seeds is below the range indicated by Domínguez et al. (2016) and higher in the weight of the fully-grown seeds per cone. Other studies report that P. pseudostrobus seeds weigh a minimum of 0.011 g and a maximum of 0.022 g (Hernández et al., 2003), inclusive values in this study in Oaxaca.

Reproductive Indicators and Climatic Variables

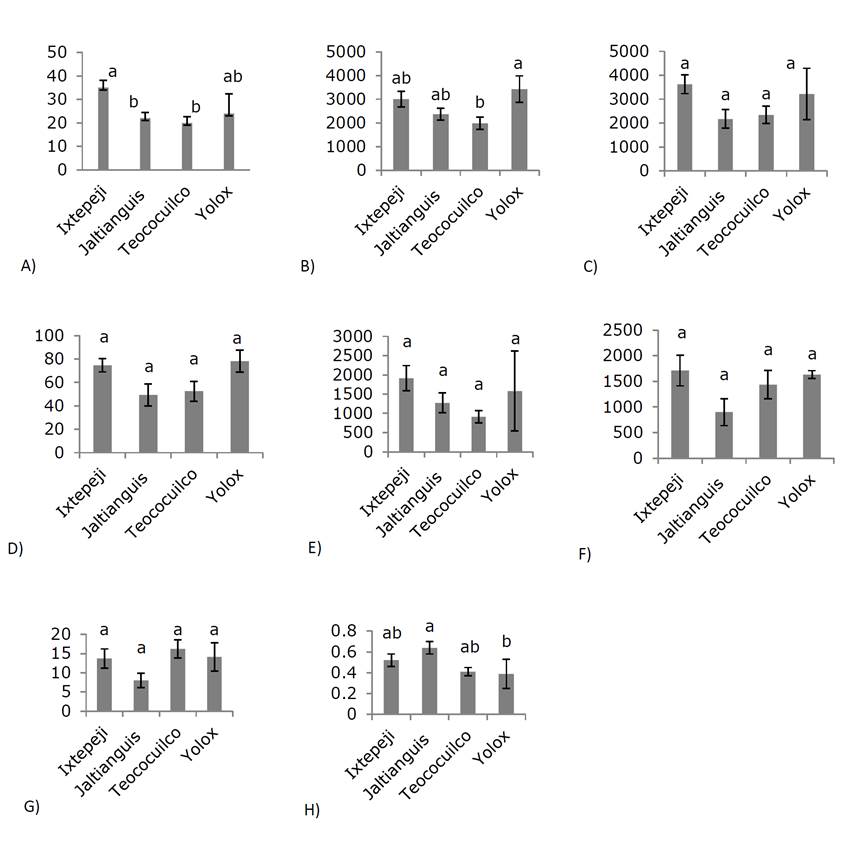

Trees from Ixtepeji produced 35 cones on average, an amount that was significantly (p ≤ 0.05) higher than the 20 and 22 cones that the trees from Teococuilco and Jaltianguis had (Figure 1A). The total cones in each tree weighed from 1 990 to 3 428 g, in which 2 174 to 3 627 seeds were obtained, which together weighed from 49.29 to 78.09 g; the total of filled seeds was from 899 to 1 712 (Figure 1B -D), magnitudes that in each case were not significantly different (Duncan, 0.05). On average, a cone collected from a tree at Yolox weighed 144.83 g, which was 66 % higher than a cone collected from a tree at Ixtepeji; In addition, 71.75 seeds came from each cone collected from a tree in Teococuilco, which was 75 % higher than the number of full seeds from each cone of the Jaltianguis trees. The filled seeds obtained from tree cones in the Yolox locality weighed 24.27 mg (Figure 1F), a magnitude 17 % higher than the weight of the individual seed obtained from trees in Ixtepeji.

A) number of cones per tree; B) cones weight per tree; C) number of full-grown seed per tree; D) weight of full-grown seed per tree; E) vain seed per tree; F) full seed per tree; G) reproductive efficiency and H) inbreeding index. Different letters on the bars represent significant differences (Duncan, 0.05) and the vertical lines on the bars indicate the standard deviation.

Figure 1 Reproductive indicators of Pinus pseudostrobus var. oaxacana (Mirov) S.G.Harrison.

In P. cembroides Zucc. (González-Ávalos et al., 2006) and P. pinceana Gordon (Quiroz-Vásquez et al., 2017) there were significant differences in cone production between evaluated years, however, not between populations. An average of 2 841.75 full-grown seeds were identified (full and empty), with an average of 1 419.5 (49.97 %) of full seeds with a minimum of 898 and a maximum of 1 712 (Figure 1E). For the same species, Domínguez et al. (2016) found 44 %, while Bello (1988) calculated 40 % of full seed; these results are higher than 7.5 % Morales-Velázquez et al. (2010) obtained in P. leiophylla, but 75.5 % lower than those found in P. pinceana (Quiroz-Vásquez et al., 2017). Of the full-grown seeds, 50.03 % were vain, a lower value than those of other conifers such as Picea mexicana Martínez (78.3 %) (Flores-López et al., 2005) and Picea martinezii T. F. Patterson (80.8 %) (Flores-López et al., 2012).

The ratio of empty seeds to developed ones (inbreeding index) varied from 0.39 to 0.64 (Figure 1H) in this study; values higher than those found in P. caribaea var. caribaea Barret y Golfari (0.26) and P. tropicalis Morelet (0.03) by Márquez (2017). This favorable behavior may be due to the fact that it is a source originally designed for seed production, for P. leiophylla the same author found a very high inbreeding index value (0.92); This can be attributed to the reduced size of the populations, which generates self-pollination (Morales-Velázquez et al., 2010). Generally, the inbreeding index is associated with low pollen abundance and quality and increased self-fertilization; in sites with low tree densities, the probability that deleterious alleles form homozygous genotypes and cause abortion of embryos, increasing the amount of vain seed (Arista and Talavera, 1996).

The average value for the reproductive efficiency of the species is 13 mg of seed per gram of dry cone, and in this context, the most efficient trees are from Teococuilco, with 16.2 mg (Figure 1G). The value was higher compared to P. leiophylla, 2.49 mg of g-1 dry cone seed (Morales-Velázquez et al., 2010), in contrast, the values are lower than those recorded in other conifers, such as P. rigida Miller, Picea mexicana Martínez, Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco, P. patula, P. pinceana, 55.3, 23.7, 29.6, 16.35 mg g-1 and 80 mg of dry cone g-1 seed, respectively (Mosseler et al., 2004; Flores-López et al., 2005; Mápula-Larreta et al., 2007; Quiroz-Vásquez et al., 2017). Reproductive efficiency is a relative indicator of the energy that a tree dedicates to seed production and is influenced by the weight and number of seeds filled per cone (Mosseler et al., 2000; Owens and Fernando, 2007; Castilleja et al., 2016); therefore, it could be assumed that the populations of the species studied in Oaxaca show signs of a decrease in their reproductive efficiency.

From significant correlations between environmental variables, characteristics of selected phenotypes and reproductive indicators, the fact that higher sites, with lower temperatures and higher rainfall favor the cones to produce more seeds (r = 0.43), of better quality, stands out. and that reproductive efficiency increases (r = 0.38), and IE decreases (r = -0.38) (Sáenz-Romero et al., 2012). On the other hand, higher values of normal diameter, age, volume and productivity of the site (r> 0.30), are associated with higher quantity and quality of cones per tree (Binotto et al., 2010); old trees produce light cones with few seeds and light ones, and the inbreeding index is favored in the lower altitude places.

Conclusions

The selected phenotypes of Pinus pseudostrobus var. oaxacana from five provenances in Oaxaca have high cone efficiency and seed production with the highest values for the San Pedro Yolox provenance. Selected trees show significant differences in 11 reproductive indicators between provenances or regions and within trees. In this way, the trees selected in San Pedro Yolox presented better reproductive indicators, with good reproductive efficiency and a low inbreeding index; These are associated with excellent environmental conditions of the natural distribution sites in Oaxaca.

Acknowledgements

To the Tecnológico Nacional de México for financing the research of the Master of Science student, through a research project “Ensayo de progenies de especies de pinos comerciales en el estado de Oaxaca”("Progeny of commercial pine species sssay in the state of Oaxaca"), code: 6844.19-P.

REFERENCES

Arista, M. and S. Talavera. 1996. Density effect on the fruit-set, seed crop viability and seedling vigour of Abies pinsapo. Annals of Botany 77(2): 187-192. Doi:10.1006/anbo.1996.0021. [ Links ]

Bello G., M. A. 1988. Potencial, eficiencia y producción de semillas en conos de Pinus pseudostrobus Lind. en Quinceo, municipio de Paracho Michoacán. Ciencia Forestal 64(13): 4-29. [ Links ]

Binotto, A. F., A. D. Lúcio and S. J. Lopes. 2010. Correlation between growth variables and the Dickson quality index in forest seelings. CERNE 16(4): 457-464. Doi:10.1590/S0104-77602010000400005. [ Links ]

Bramlett, D. L., E. W. Belcher, G. L. DeBarr, J. L. Hertel, R. P. Karrfalt, C. W. Lantz, T. Miller, K. D. Ware and H. O. III Yates. 1977. Cone analysis of southern pines: a guidebook. Gen. Tech. Rep. SE-13. USDA For. Ser. Ashville, NC, USA. 28 p. [ Links ]

Bustamante-García, V., J. A. Prieto-Ruíz, E. Merlín-Bermudes, R. Álvarez-Zagoya, A. Carrillo-Parra and J. C. Hernández-Díaz . 2012. Potencial y eficiencia de producción de semilla de Pinus engelmannii Carr. en tres rodales semilleros del estado de Durango, México. Madera y Bosques 18(3): 7-21. Doi:10.21829/myb.2012.183355. [ Links ]

Castellanos A., D., C. Sáenz R., R. A. Lindi C., N. M. Sánchez V., P. Lobbit. y J. C. Montero C. 2013. Variación altitudinal entre especies y procedencias de Pinus pseudostrobus, P. devoniana y P. leiophylla. Ensayo de vivero. Revista Chapingo Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente 19(3): 399-411. Doi:10.5154/r.rchscfa.2013.01.002. [ Links ]

Castilleja S., P., P. Delgado V., C. Sáenz-Romero and Y. Herrerías D. 2016. Reproductive success and inbreeding differ in fragmented populations of Pinus rzedowskii and Pinus ayacahuite var. veitchii, two endemic Mexican pines under threat. Forests 7: 1-17. Doi:10.3390/f7080178. [ Links ]

Corral-Rivas, J. J. y B. Vargas-Larreta. 2013. Sistema biométrico para la planeación del manejo forestal sustentable de los ecosistemas con potencial maderable en México (2013-C01-209772): Oaxaca. Conafor-Conacyt. Oaxaca,Oax., México. 75 p. [ Links ]

Domínguez C., P. A., J. J. Navar C., M. Pompa G. y E. J. Treviño G. 2016. Producción de conos y semillas de Pinus pseudostrobus Lindl. en Nuevo León, México. Foresta Veracruzana 18(2): 29-36. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/497/49748829004.pdf (18 de diciembre de 2019). [ Links ]

Espinoza H., M., J. Márquez R., J. Alejandre R. y H. Cruz J. 2009. Estudio de conos de Pinus pseudostrobus Lindl. en un relicto de la localidad el paso, municipio de la Perla, Veracruz, México. Foresta Veracruzana 11(1): 33-38. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/497/49711999006.pdf (1 de diciembre de 2019). [ Links ]

Flores-López, C., J. López-Upton y J. J. Vargas-Hernández. 2005. Indicadores reproductivos en poblaciones naturales de Picea mexicana Martínez. Agrociencia 39(1): 117-126. [ Links ]

Flores-López, C. , C. G. Geada-López, J. López-Upton y E. López-Ramírez. 2012. Producción de semillas e indicadores reproductivos en poblaciones naturales de Picea martinezii T. F. Patterson. Revista Forestal Baracoa 31(2): 49-58. http://www.actaf.co.cu/revistas/rev_forestal/Baracoa-2012-2/FAO2%202012/PRODUCCI%C3%93N%20DE%20SEMILLAS%20E%20INDICADORES.pdf (10 de diciembre de 2019). [ Links ]

González-Ávalos, J., E. García-Moya, J. J. Vargas-Hernández, A. Trinidad-Santos, A. Romero-Manzanares y V. M. Cetina-Alcalá 2006. Evaluación de la producción y análisis de conos y semillas de Pinus cembroides Zucc. Revista Chapingo. Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente 12(2): 133-138. [ Links ]

Gómez J., D. M., C. Ramírez H., J. Jasso M. y J. López U. 2010. Variación en características reproductivas y germinación de semillas de Pinus leiophylla Schiede ex Schltdl. & Cham. Revista Fitotecnia Mexicana 33(4): 297-304. https://www.revistafitotecniamexicana.org/documentos/33-4/3a.pdf (8 de diciembre de 2019). [ Links ]

Hernández C., O., E. O. Ramírez G. y L. Mendizábal H. 2003. Variación en semillas de cinco procedencias de Pinus pseudostrobus Lindl. Foresta Veracruzana 5 (2):23-28. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/497/49750204.pdf (5 de noviembre de 2019). [ Links ]

Kimmins, J. P. 2004. Forest ecology. A foundation for sustainable management and environmental ethics in forestry. Prentice Hall. Upper Saddle River, NJ USA. 611 p. https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/14660075?selectedversion=NBD42245093 (28 de marzo de 2019). [ Links ]

Krannitz, P. G. and T. E. Duralia. 2004. Cone and seed production in Pinus ponderosa: a review. Western North American Naturalist 64(2): 208-218. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan/vol64/iss2/8 (11 de diciembre de 2019). [ Links ]

Leyva-Ovalle, Á. y J. J. Vargas-Hernández. 2018. Establecimiento de huertos semilleros asexuales regionales y ensayos de progenie de Pinus pseudostrobus para la evaluación genética de los progenitores. Infome final etapa 2. Proyecto 277784. Fondo Sectorial Conafor-Conacyt. México, D.F., México. 23 p. [ Links ]

López-Upton, J. 2002. Pinus pseudostrobus Lindl. In: Vozzo A., J. A. (ed.). Tropical Tree Seed Manual. USDA Forest Service. Washington, DC, USA. pp. 636-638. Doi:10.1093%2Faob%2Fmch046. [ Links ]

Mápula-Larreta, M., J. López-Upton, J. J. Vargas-Hernández y A. Hernández-Livera. 2007. Reproductive indicators in natural populations of Douglas-fir in Mexico. Biodiversity and Conservation 16(3): 727-742. Doi:10.1007/s10531-005-5821-y. [ Links ]

Márquez G., A. V. 2007. Variación de conos y semillas de Pinus pseudotrobus Lindl. del Esquilón, Coacoatzintla, Veracruz, México. Tesis de maestría. Instituto de Genética Forestal. Universidad Veracruzana. Xalapa, Ver., México. 48 p. [ Links ]

Márquez B., C. 2017. Indicadores reproductivos de dos áreas productoras de semillas en Pinus caribaea var. caribaea y Pinus tropicalis. Revista Científico Estudiantil Ciencias Forestales y Ambientales 2(1): 21-29. http://cifam.upr.edu.cu/index.php/cifam/article/view/66/66 (15 de noviembre de 2019). [ Links ]

Morales-Velázquez, M. G., C. A. Ramírez-Mandujano, P. Delgado-Valerio y J. López-Uptón. 2010. Indicadores reproductivos de Pinus leiophylla Schltdl. et Cham. en la cuenca del río Angulo, Michoacán. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 1(2): 31-38. Doi:10.29298/rmcf.v1i2.635. [ Links ]

Mosseler, A., J. E. Major, J. D. Simpson, B. Daigle, K. Lange, Y. S. Park, K. H. Johnsen and O. P. Rajora. 2000. Indicators of population viability in red spruce, Picea rubens. I Reproductive traits and fecundity. Canadian Journal of Botany 78 (7): 928-940. Doi:10.1007/s10592-004-1850-4. [ Links ]

Mosseler, A. , O. P. Rajora, J. E. Major and K. H. Kim. 2004. Reproductive and genetic characteristics of rare, disjunct pitch pine populations at the northern limits of its range in Canada. Conservation Genetics 5(5): 571-583. Doi:10.1007/s10592-004-1850-4. [ Links ]

Muñoz-Flores, J. , J. A. Prieto R., A. Flores G., M. Alarcón B. y T. Sáenz R. 2013. Selección de árboles superiores del género Pinus. SAGARPA-INIFAP. México, D.F., México. 59 p. [ Links ]

Owens, J. N. and D. Fernando. 2007. Pollination and seed production in western white pine. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 37: 260-275. Doi: 10.1139/X06-220. [ Links ]

Quiroz-Vázquez, R. I., J. López-Upton, V. M. Cetina-Alcalá y G. Ángeles-Pérez. 2017. Capacidad reproductiva de Pinus pinceana Gordon en el límite sur de su distribución natural. Agrociencia 51(1): 91-104. [ Links ]

Ramírez-Sánchez, S. E., J. López-U., G. García S., J. J. Vargas-Hernández, A. Hernández-Livera y Ó. J. Ayala-Garay. 2011. Variación morfológica de semillas de Taxus globosa Schltdl. provenientes de dos regiones geográficas de México. Revista Fitotecnia Mexicana 34(2): 93-99. [ Links ]

Rodríguez L., R., R. Razo Z., J. Juárez M., J. Capulín G. y R. Soto G. 2012. Tamaño de cono y semilla en procedencias de Pinus greggii Engelm. var. greggii establecidas en diferentes suelos. Revista Fitotecnia Mexicana 35 (4): 289-298. [ Links ]

Sáenz-Romero, C., G. E. Rehfeldt, N. L. Crookston, P. Duval, R. St.-Amant, J. Beaulieu and B. A. Richardson. 2010. Spline models of contemporary, 2030, 2060 and 2090 climates of Mexico and their use in understanding climate-change impacts on the vegetation. Climatic Change 102: 595-623. Doi: 10.1007/s10584-009-9753-5. [ Links ]

Sáenz R., J. T., H. J. Muñoz F. y A. Rueda S. 2011. Especies promisorias de clima templado para plantaciones forestales comerciales en Michoacán. INIFAP, Campo Experimental Uruapan. Uruapan, Mich., México. 213 p. [ Links ]

Sáenz-Romero, C. , S. Aguilar-Aguilar, M. Á. Silva-Farías, X. Madrigal-Sánchez, S. Lara-Cabrera y J. López-Upton. 2012. Variación morfológica altitudinal entre poblaciones de Pinus devoniana Lindl. y la variedad putativa cornuta en Michoacán. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 3(13): 17-28. Doi:10.29298/rmcf.v3i13.486. [ Links ]

Salaya-Domínguez, J. M., J. López-Upton y J. J. Vargas-Hernández. 2012. Variación genética y ambiental en dos ensayos de progenies de Pinus patula. Agrociencia 46:519-534. [ Links ]

Statistical Analysis System (SAS). 2004. SAS/STAT users’ guide, Version 9.1. SAS Institute Inc. Raleigh, NC, USA. 5136 p. https://support.sas.com/documentation/onlinedoc/91pdf/sasdoc_91/stat_ug_7313.pdf (30 de noviembre de 2019). [ Links ]

Secretaria del Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Semarnat). 2016. Anuario Estadístico de la Producción Forestal 2015. México. pp. 143-145. https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/282951/2016.pdf (11 de enero de 2019). [ Links ]

Vallejos, J., Y. Badilla, F. Picado y O. Murillo. 2010. Metodología para la selección e incorporación de árboles plus en programas de mejoramiento genético forestal. Agronomía Costarricence 34(1): 105-119. https://biblat.unam.mx/hevila/AgronomiaCostarricense/2010/vol34/no1/11.pdf (5 de noviembre de 2019). [ Links ]

Viveros V., H., C. Sáenz R., J. López U. y J. J. Vargas H. 2005. Variación genética altitudinal en el crecimiento de plantas de Pinus pseudostrobus Lindl en campo. Agrociencia 39(5): 575-587. [ Links ]

Viveros V., H. , A. R. Camarillo L., C. Sáenz R. y A. Aparicio R. 2013. Variación altitudinal en caracteres morfológicos de Pinus patula en el estado de Oaxaca (México) y su uso en la zonificación. Bosque 34(2): 173- 179. Doi: 10.4067/S0717-92002013000200006. [ Links ]

WorldClim. 2019. WorldClim WorldClim https://worldclim.org/bioclim (15 de marzo de 2019). [ Links ]

Received: November 22, 2019; Accepted: March 13, 2020

texto en

texto en