Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

versão impressa ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.8 no.7 Texcoco Set./Nov. 2017

Essays

The designation of origin of rice of Morelos: linkage and conformation of networks

1Instituto de Investigaciones Económicas-UNAM. Circuito Mario de la Cueva, Ciudad de la Investigación en Humanidades, Ciudad Universitaria. CP. 04510. Ciudad de México. Tel. 01(55) 56230129 y 01(55) 56230100, ext. 42433.

2Facultad de Economía-UASLP. Av. Pintores S/N, Fraccionamiento Burócratas del Estado. San Luis Potosí, SLP, México. CP. 78263. Tel. (52) 4448131238, ext. 7056. (leonardotenorio@hotmail.com).

In 2012, Mexico received the designation of origin (DO) for the state of Morelos rice, which was the result of a close and very long-term relationship between producers, federal and local government agencies, and researchers from the National Institute of Forestry, Agriculture and Livestock Research (INIFAP)-Zacatepec Experimental Field. In particular, the constant communication between INIFAP producers and researchers allowed them to respond quickly to technical problems of production and facilitated the incorporation of constant technological innovations with direct effects on productivity and competitiveness. The contribution of this work will be the identification of the actors involved and their degree of participation in the conformation of the network that gave the final result, although not unique, the obtaining of the DO. As well as understanding how this linkage between actors, who are the relevant actors and who are the subsidiaries and in general identify the dynamics between the local actors. The tool used for the identification of the network, is known as analysis of social networks (ARS). The ARS was made from 15 semi-structured and in-depth interviews conducted in the state of Morelos between 2013 and 2015 to producers, government representatives, and researchers from INIFAP. It is concluded that the appellation of origin is the result of a series of endogenous and organizational processes that open new and wide possibilities to the members of the network

Keywords: innovation; social and economic development; social network analysis

En 2012 se otorgó en México la denominación de origen (DO) para el arroz del estado de Morelos, la cual fue resultado de una vinculación estrecha y de muy largo plazo entre productores, organismos gubernamentales federales y locales, así como de investigadores del Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP)- Campo Experimental Zacatepec. Particularmente la constante comunicación entre los productores e investigadores del INIFAP les permitió responder rápidamente a problemas técnicos de producción y les facilitó la incorporación de constantes innovaciones tecnológicas con efectos directos sobre la productividad y competitividad. La aportación de este trabajo será la identificación de los actores involucrados y su grado de participación en la conformación de la red que dio como resultado último, aunque no único, la obtención de la DO. Así como entender cómo es esa vinculación entre actores, quiénes son los actores relevantes y quiénes son los subsidiarios y en general identificar la dinámica entre los actores locales. La herramienta utilizada para la identificación de la red, es conocida como análisis de las redes sociales (ARS). El ARS se hizo a partir de 15 entrevistas semiestructuradas y a profundidad realizadas en el estado de Morelos entre 2013 y 2015 a productores, representantes gubernamentales, e investigadores(as) del INIFAP. Se concluye que la denominación de origen es resultado de una serie de procesos endógenos y organizativos que abren nuevas y amplias posibilidades a los integrantes de la red.

Palabras clave: análisis de redes sociales; desarrollo social y económico; innovación

Background

In order to explain regional economic development, in recent decades attention has been paid to the importance of local actors in the development of specific geographic spaces, focusing attention on particular endogenous conditions that make a certain space a place conducive to the development of some type of economic activity, where the linkage and transfer of knowledge are indispensable for achieving greater efficiency, productivity and innovation that contributes to regional development.

One of the most successful linkages, at the international level, for economic growth is that established between productive sectors and universities and research centers. At first, academic and research institutions were given a nearly exclusive role of knowledge production, which has evolved, within the framework of the complexity of today’s society, and has been extended to solving problems and demands of the business sector and society in general (López et al., 2006). It was in the 1980s that the relationship between academia and the productive apparatus began to be strengthened, where the university-industry linkage constitutes an alternative to the intensification of competition on an international scale, since it is based on processes of continuous innovation.

The cooperation of higher education and research institutions becomes a key element for the solution of problems, while taking into account other relevant elements in the linking process.

In the case of Mexico, the studies that have been carried out to analyze the link between academia and society show that this is sporadic and generally does not conclude in successful experiences, since there is a lack of knowledge and distrust on the part of the companies and productive sectors on the activities carried out by universities, institutes and research centers, while on the part of the former, the lack of interest in participating in productive activities is evident given the lack of incentives to promote them (Castaños, 1999; Tenorio, 2007; Rosales and Gómez, 2010).

It is in this sense that this work takes relevance, having as hypothesis that: “the denomination of origin of the rice of Morelos is a result of the connection and conformation of networks of diverse local actors among which the linkage between the producers of rice of Morelos and the researchers of the National Institute of Forestry, Agriculture and Livestock Research (INIFAP)-Zacatepec Experimental Field, which made possible, among other things, the genetic improvement of the rice product of constant flows of information and communication that originated to a product of unique quality”.

Starting from the idea that technological change is an endogenous process to the productive process itself, the analytical approach of the evolutionary theories that recover the macroeconomic fundamentals of the economic dynamics and institutionalist analysis of the development represented by Cimoli y Dosi (1995); Nelson (1993); Pérez (1983, 1992); Freeman (1995); Porter (1990); Lundvall (1992), in order to understand learning processes and operational routines as something that can be modified over time and in socio-spatial contexts determined, which causes that if something happens somewhere, this will necessarily replicate in another.

Perez (1992) argues that behavior is rooted in institutions that allow the interrelation of economic actors able to harmonize efforts for the creation of appropriate new institutions to promote innovation and thus generate changes (Perez 1992; Chavero et al., 1997). In this sense, the analysis focuses on the task of institutions since they are instances that can promote and constrain the formation of certain habits, routines and social practices that reproduce the whole of social life where the habits and routines of subjects or organizations will be able to reproduce, regulate and coordinate social actions, including the economic performance of a particular place (Nelson and Sampat, 2001).

Thus, the institutional environment (a system of formal and informal conventions, customs, norms and social routines) and institutional arrangements (particular organizational forms: markets, firms, unions, associations, etc) are important elements closely linked to the innovation process through its capacity to generate and incorporate knowledge, to the economic and territorial dynamism (Martin, 2000; Hogson, 2007; Rosales, 2010). It is considered that the success of institutional arrangements in the organizational dynamics of socioproductive activity comes from networks of cooperation between the various local actors as pointed out later.

Authors such as Glüker (2013) mention that the theme of regional development is intrinsically related to the conformation and consolidation of economic networks and the interaction between them. For its part Granovetter (2005) reports that there is evidence to support the view that social relations have an impact on economic performance, which contributes to the link between regions and territories and their development, because actors such as companies, universities, centers of research and development, as well as government agencies tend to have common objectives and that when seeking a better performance are naturally linked, which is related to the theory of networks that understands the interactions between nodes as networks, allowing the analysis of markets and relations between firms as such (White, 1981; Baker, 1990).

Here, the central point is the interactions or relationships that the actors establish, because from them one can infer expectations about individual or collective actions (Mizruchi, 1994; Gulati, 1998) that allow the definition of structures that affect their performance and with this the regional economic performance, but also determine aspects of the behavior of the actors in the network, who can be considered dominant or determinant actors, playing a relevant role in the performance of the same.

Returning these elements and concepts outlined will validate the hypothesis with the help of the analysis of social networks (ARS) as will be seen in the following section.

Methodology

Identifying, measuring collaboration and degree of involvement of a network, which can be formal or informal, it allows us to understand in what sense and how to give, strengthen and emphasize the relationships that lead to and from situations of technological change, innovation, development economic and social at the regional level, as well as social capital formation, which makes the analysis of social networks (ARS, for its acronym in Spanish) a powerful tool for the realization of these tasks.

The ARS has its origins in the early works of sociometry of Moreno (1934) for the study of formal properties of social networks, uses graph theory to define actors as nodes and their relationships as edges or arcs (depending on whether the relationship is univocal or biunivocal) and thus associate a graph G, where G={V, X} and V are the actors and X are the relations that the actors establish between them (Lozares 1996), with different types of links or relationships if: i) actors and their actions are interdependent; ii) relational ties are transfers of material and non-material resources; iii) network models identify economic, political, social, etc structures as constant patterns of relationship (Wasserman and Faust, 1994; Izquierdo and Hanneman, 2006), or as in our case; and iv) networks derive from the achievement of economic, social and political objectives.

Concepts such as the density of a network, or how connected the actors are, the connectivity, or through how many actors one of them is communicated and the centrality, which denotes the nodal degree, or number of ties related to a node, to closeness or minimum distance between nodes and the intermediation, or frequency with which a node appears, are elements that will allow us to define structurally the networks, how and who make them, besides justifying assertions about the preponderance, importance and transcendence of the actors towards its network and the objectives it pursues (Velázquez and Aguilar, 2005).

The ARS is strengthened by graphical analysis, which exploits force-directed algorithms such as the Kamada Kawai (KK) to transform the vertices of a network into springs proportional to the graphical distance of the vertices (Hu, 2006), which allows visually that the edges become springs that make those nodes or actors with greater bonding concentrate more force and this takes them to occupy central places in the graph and in the same way make those with fewer ties tend to occupy peripheral locations, which translates into a quick visual identification of the degree of linkage or preponderance that nodes occupy to the network and thereby determine the specific weight of the actors in the network.

However, based on semi-structured interviews, field studies and bibliographic documents, it was possible to identify fifteen actors, among individuals and public and private organizations, who have participated and are considered part of the Morelos rice network, which explains the of the DO of the rice, as a process of conformation of the “Morelos rice network” and that when linked have made possible the creation and incorporation of technological changes in the processes to generate a very specific type of rice in a region and in ultimately, the DO, accompanied by increasing productivity as a result of constant innovation, with positive social and economic effects for the development of the activity and the region.

In order to determine and measure the performance and the degree of linkage between the actors, a square matrix of double entry was constructed (it can be consulted in annex) that represents, by means of numbers, the existence or not of links and relations between them, where an integer greater than zero represents the existence and degree of linkage between two actors; the greater the number, the greater the bond, while if it is assigned a zero, that will mean the nonexistence of the latter.

Therefore, the numerical value will represent the existence or not of some linkage between actors through types of relations such as: productive and economic historical or hierarchy, contracts or laws that link them; information flows, knowledge, human and material resources, or feedback, what is necessary to recognize the existence or not of links and in particular case to see the closeness that some key players have to result in the increasing productivity, innovation and performance productive. The linkage will be considered relational when there is feedback between two nodes in a biunivocal and functional way when the flow of information goes in only one direction, which will be represented by arrows for the first case and edges for the second.

Discussions

The Morelos rice has characteristics that distinguish it from other types of rice, which is a result of the physiographic peculiarities of the region and that allowed the rice to germinate with qualities different from those of other regions, characteristics such as the white belly, located in the center of the grain, which is a product of the accumulation of starch favored by high temperatures during the day and cool at night, reducing nocturnal respiration of the plant while producing higher levels of crop development (INIFAP, 2011).

This special feature was the one that initially motivated the research interest of INIFAP and some of its researchers since the 1940s, in addition to its average yield of 23 servings per cup as opposed to the 18 servings it gives a cup of rice of any other variety and its efficient cooking (of only 30 min against the average of other rice of 40-45 min) (IMPI, 2011).

The current quality of Morelos rice has been largely the result of the research carried out at INIFAP, Zacatepec Field Experimental, a public center dedicated to research on various crops, which has rice as one of the most studied products due mainly to the history and tradition that keeps the crop in the region.

In particular, INIFAP has a quality laboratory that tests germplasm, gelatinization and tasting (important tests that enable or not the release of new varieties of rice) and where rice grains of national and different Latin American countries are analyzed.

As can be observed, the physiographic characteristics of the entity are important for the crop; however, other factors have also been determinant for its development. One of the most relevant is the ancestral tacit knowledge that rice producers have transmitted from generation to generation, which is present in each of the phases of the production process from planting of seedlings, the approach, transplantation, fertilization, weeding (also known as tlamateca), to “pajareo” and harvesting, activities that are usually done manually.

Thus, Morelos rice harvested today is a product of tacit knowledge and genetic improvement through conventional methods through crosses between the same rice varieties.

This genetic improvement began in the 1980s, based on collections of ecotypes (of plants living in the study area) that measured more than 1.5 meters in height which caused the plant to have a vast foliage that gave a grain which looked like stained, which they called “meco”. The “meco” gave origin to the same Jojutla variety that from improvements resulted in the seed that is sown in Morelos, as mentioned by a researcher of INIFAP “... the INIFAP has the seed, which is of different categories, original seed we sow it and from there you get the basic seed, after the basic seed you get the certified seed and this seed we sell it to the producer which in turn can produce the seed certified for planting” (interview July 3, 2013).

Also, INIFAP investigators through their research have found ways to control pests, for example, in the 1980s controlled the drainage of the plant and between 2013 and 2014 were interested in controlling the staining of the grain.

Without a doubt, the genetic improvement and research carried out by INIFAP has made it possible to obtain a higher yield since the 80’s, when 6.7 t were obtained until reaching 10.07 t per hectare by 2014 (SIAP, 2016), placing Morelos in the first place of productivity at national level.

Such genetic improvement would not have been possible without the close link between producers and researchers and the institutional arrangements that translate into a close relationship of cooperation and trust between the two actors and that was reflected in the interviews with producers, who they did not hesitate to consult INIFAP researchers for any problems with their cultivation. It was also found that the producers carry out the indications or experiments of the researchers in their plots, thus supporting the research and development of the crop, where most of the cost has been constantly absorbed by the producer. This cooperation has been maintained for long periods of research on rice cultivation where institute researchers have been engaged in researching the problem for years.

As mentioned, there is generally little linkage between the academy and the productive sectors; however, in the case of INIFAP this has not happened, at least in the study that is presented, since the rice research in the Institute depends totally on the needs of its producers, since the resource is given to researchers only if the project is approved by the rice farmers as mentioned by one of the researchers: “... we have to have a letter from the producers in which they are endorsing the project and with the products to be obtained ... if we do not have that letter, we cannot carry out the project because it must be in accordance with the demand ...”.

Subsequently, when the project is approved, a meeting is again held with the producers with whom it is possible to obtain a dialogue, and for how long, a matrix is elaborated in which the research objective is specified and presented to the foundation PRODUCE who is finally the one who decides if the project is approved.

Previously, according to interviews conducted, the resource to carry out the research came directly and the researchers had more freedom to decide the research work they intended to do. This situation has two important aspects: 1) when the researcher (a) establishes the first dialogue with the producer, the latter can argue that there is some other problem that requires an early intervention and reorient the research towards it, which undoubtedly helps to solve problems of productive activity; and 2) the producer can, at a certain moment, slow down the project or research on a problem that the researcher has previously identified if the producer does not think that this is a real need or is determined that something is solved time does not have the same impact or transcendence as the original project raised by the researcher (a) although so far this last point has not been the case of the actors involved in rice cultivation since practically the total number of times the problem a has been identified by both producers and researchers.

Another element to be considered in the linkage of producers and INIFAP is undoubtedly its strategic geographical location of the latter, since the Zacatepec Experimental Field is located in the immediate vicinity of rice producing areas, allowing researchers a displacement and important knowledge of the region. In this sense, the research focus of INIFAP on rice also plays a relevant role in the response to the demands of knowledge and technological innovation of rice farmers.

In this regard, it can be said that for a couple of years INIFAP researchers have tried to convince and train rice producers to implement the system of direct sowing of rice with mechanized edges, in July of the year 2014 they obtained a demo plot of direct sowing in which they explained to the producer how to plant and what would be the advantage of doing so. Undoubtedly this innovation to be applied by most of the producers of rice in the state of Morelos would be an important advance for them since “... is expected to save in the process of planting, time and resources by avoiding do the transplant. Similarly, water will be saved since direct seeding only needs water twice a week, unlike the transplant planting that needs water all week” (Tolentino and del Valle, 2014). They are also proposing the acquisition of laser levelers that allow the absorption of water and fertilizers homogeneously on the surface of planted rice.

Referring to the theory, the adaptations and changes in operational routines that can be realized thanks to the socioproductive and spatial context in which the crop is developed, as well as the flexibility and confidence existing between the parties are being considered. In this sense the institutional environment and the institutional arrangements represented in this case by the associations of rice producers of the state of Morelos are closely linked to the innovation processes that are generating new productive and institutional dynamics, the DO is a clear example.

The history of the acquisition of the DO begins in 1994, when the producers organize themselves to obtain help of the local government and of the INIFAP. However, it is until February 16, 2012 that the designation of origin for the “rice of the state of Morelos” is achieved. With the denomination of origin the plant, the seed and the grain of the plant of “rice of the state of Morelos” was protected. Specifically, the finished products covered by the appellation of origin are: a) “rice from the state of Morelos” palay; b) “brown rice of the state of Morelos”; c) “Morelos state rice” polished; and d) By-products of “Morelos state rice”: husk, half grain, three quarters of grain, granillo, bran and flour. The designation of origin (DO), which is an internationally recognized legal figure “is defined as that which uses the name of a region or geographical place of a country to designate an originating product whose quality or characteristics are exclusively due to that environment geographical, resulting from natural and human factors” (LPI, 2010)

In this case the DO was obtained due to the particularities of the grain, its excellent quality and the physiographic goodness of the region but, above all, to the genetic improvement made by the INIFAP researchers and the producers’ organization, which opened a window of opportunities to compete in the national market and even international. In this process, INIFAP once again played an important role in facilitating the research carried out on campus over the years as well as the works that certified the quality, genetic and nutritional characteristics of Morelos rice.

At the time of the interviews, the producers had requested INIFAP’s assistance in obtaining the Morelos state rice standard, which was submitted in June 2015, so that interested parties could comment and which was finally approved unanimously in November 2016. The Official Mexican Standard NOM-080-SCFI-2016, Morelos State rice is constituted as an instrument for the protection of consumer interests since it establishes the physico-chemical specifications, test methods to demonstrate compliance with the standard and commercial information that should be included in the labels for grain sale (NOM NOM-080- SCFI-2016).

With the help of the Pajek (free software program used internationally for the analysis of networks for their versatility and constant progress) in the definition of the relations established by the actors in the rice network and that was reflected in the relational matrix, we see that it achieves a level of density of 72%, implying a level of linkage between nodes very high, since the degree of density of a network is established from the quotient between the number of existing links and the number of possible links, i.e. D= r/N(N-1) .Where r is the number of existing links and N is the number of actors. Where the closest linkage is in those actors in charge of the productive, financial and innovation areas that contributed to the obtaining of the DO

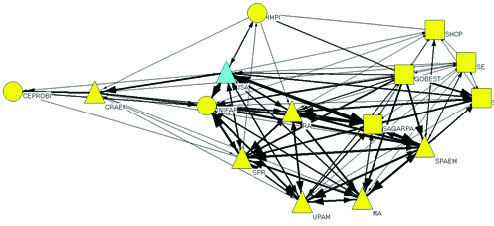

In Figure 1, which is the result of the application of certain functions and indicators, shows the set of actors separated according to the number of relationships or leagues. Where in the most central part are, as we said, those in charge of the financial, productive and innovation. In order to identify the actors, those represented by a triangle interact in the productive field, among them: Mr. Jesús Solís A. (JSA), non-governmental representative to the product system, rice mills (MA), agricultural representatives (RA), rural production companies (SPR), union of Morelos rice producers (UPAM), the rice product system (SPA) and the Morelos State Rice Regulatory Board (CRAEM); the innovation circle: INIFAP, the biotic products center (CEPROBI) and the Mexican Institute of Industrial Property (IMPI) and the squares by governmental actors at the federal and state levels: Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Development Rural Fisheries and Food (SAGARPA), which participates actively from the PRODUCE Foundation, Ministry of Finance and Public Credit (SHCP), Ministry of Economy (SE), Secretariat of Agricultural Development (SEDRAGO), state-dependent and State Government , who has a subsidiary participation in the development of the region.

Figure 1 The nodal degree of the rice network. Elaboration based on interviews and documentary information.

The highest nodal degree, which implies who has the greatest number of links, has the non-governmental representative (JSA) before the product system, who has been the communication and information link between producers in all economic areas and INIFAP, which, due to its level of knowledge, has allowed it to be a direct partner of the innovation processes together with INIFAP and is evident in Figure 1, which shows it in a central position by the number of relationships it reaches.

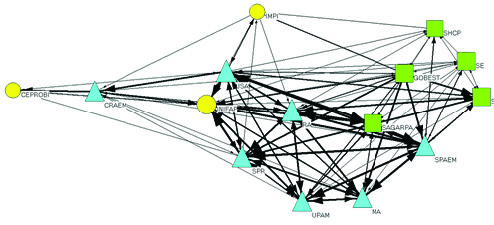

The degree of closeness between actors that Pajek generates and that is understood as the influence capacity or power of some actor over another or others, is presented in Figure 2, which is similar to the previous one, but in which the strong relationship between the majority of actors.

Figure 2 Level of closeness of the rice net. Elaboration based on interviews and documentary information.

Also in Figure 2, the non-governmental representative (JSA) and INIFAP are the most actively involved with agricultural representatives and rural representation societies, allowing information to flow to other actors, providing them with information flows and knowledge that positively affect production with the improvement genetic. To the extent that the actors are decentralized from the graph, to that extent it is understood that their contributions are less transcendental in the productive and innovation field, so they occupy places in the periphery, such are the cases of federal government agencies and state. However, in applying the KK algorithm, the figure allows us to observe that central sites are being occupied, mainly but not exclusively, by actors in the productive sector, who together with INIFAP obtain the results of productive efficiency, technological change and innovation.

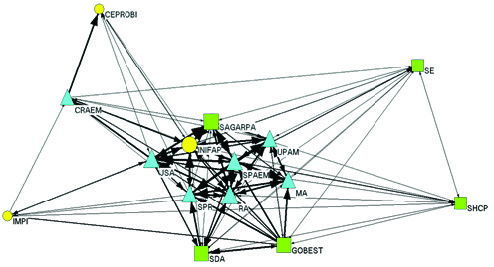

While considering the closeness between actors, that is a result of both the number of links and their magnitude and that is revealed graphically with the thickness of the arrows where the greater thickness and greater linkage vice versa, allows us to locate two groups of actors, one of the central actors whose linkage generates social capital, understood as the degree of trust, collaboration, reciprocity, that allow to reach and increase productive efficiency and innovation as a result of the establishment of rules and the establishment of institutions. In this sense, the researchers of the institutes to carry out their research have required and counted on the support of the productive organizations, who benefited from the contributions of the former have been linked and collaborating for the results and benefits that have obtained product of the incremental innovations that together and over time explain the DO.

The second group, formed by those less involved with the productive and innovation areas, are actors that carry out activities of direct or indirect support to financing and innovation such as SAGARPA. Its work is more supplementary, which does not mean that it is not transcendental in technology and innovation, since in understanding the importance of the work done, they collaborate so that financial resources, institutional, organizational and legal support flow, which avoids the possible untying of the research and development and production nodes and thus ensure that the dynamics of innovation and technological change do not stop and impact on the expansion of knowledge and the specialization of human resources and the strengthening of the ties between the network (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Centrality of the rice network, from the KK algorithm. Elaboration based on interviews and documentary information.

The Morelos State Rice Regulatory Board (CRAEM), originated in the institutional environment and through institutional arrangements, deserves a mention, since its functions have not been fully implemented, but it is hoped that in the near future to comply with activities that contribute to the redefinition of the network, allowing it to locate economic and business opportunities based on obtaining the DO and thus institutionalize the processes of technological change and innovation, analyzing the present and future needs and with to form new niches of national and international markets in which it is possible to participate and obtain benefits given the competitive advantages achieved.

This would allow a rethinking of what would or should be the DO as a mechanism to boost regional development, which will be possible with the incorporation of actors that deepen the degree of educational development and the formation of human capital related to industry.

Conclusions

The historical and socio-productive context of Morelos rice has allowed an important link between INIFAP producers and researchers, translated not only into an increase in rice productivity in the region, but also to institutional support that has been used by producers to achieve side.

The research carried out by INIFAP specialists and the collaboration with the actors of the rice network has allowed a differentiation of the grain of Morelos from others that are planted in Mexican and foreign territory originated by the physiographic, productive, research and development particularities, as well as innovation around it.

In this sense, the ARS allowed us to identify, measure and analyze the degree of linkage present in the group of organizations, companies and individuals responsible for obtaining the DO for Morelos rice, which is largely a result of the genetic improvement carried out by researchers from INIFAP and from the collaboration and feedback of the rice network around them, especially the non-governmental representative, who clearly plays a preponderant role in all the parts that integrate the process of innovation and DO.

The conformation of the network, which means the sum of knowledge and interests for a common good and which is understood as the creation of social capital because it means the generation of efficiencies that can be quantifiable in economic terms and that benefit the whole with the formation of rules and institutions that positively impact it, includes entities from various fields and extractions such as public and private, state and federal, those who maintain and maintained a direct or indirect close collaboration and increasingly effective communication, which resulted in the constant creation of innovations and in the DO.

Given the achievements and opportunities generated by the DO, it is possible and must continue in the path of productive efficiency and innovation, as it seeks to develop and incorporate more actors that allow a broader professionalisation by creating institutions and agencies in administrative and organizational, business, labor, economic and legal aspects, such as the recently created Morelos state rice regulatory council, which will allow them to take advantage of, consolidate and expand the benefits of the appellation of origin, as well as present and future innovations that will allow expand their markets of influence, by making Morelos rice available to different markets and involving more and more economic and social actors from this and other regions that allow them to advance in the professionalization of marketing and distribution methods, and to achieve their objectives.

Literatura citada

Baker, W. E. 1990. Market networks and corporate behavior. Ame. J. sociol. 96(3):589-625. [ Links ]

Carrillo, L. 2007. Los destilados de agave en México y su denominación de origen. Ciencias. 87(2):40-49. [ Links ]

Castaños, L. H. 1999. La torre y la calle. Colección Jesús Silva Herzog. UNAM- IEC- Miguel Ángel Porrúa. Librero (Ed.). D. F. México. 185 p. [ Links ]

Chavero, A.; Chávez, M. y Rodríguez, S. M. 1997. Vinculación universidad-estado-producción: el caso de los posgrados en México. México, D. F. Siglo XXI. 1678 p. [ Links ]

Glückler, J. 2013. Geografía económica y evolución de redes. In: la geografía y la economía en sus vínculos actuales. Una antología comentada del debate contemporáneo. Valdivia, L. M. y Delgadillo, M. J. (Coords.) IIEc/UNAM/CRIM/UNAM. Cuernavaca, Morelos, México. 610 p. [ Links ]

Granovetter, M. 2005. The impact of social structure on economic outcomes. J. Econ. Persp. 19(1):33-50). [ Links ]

Grossman, S. 1987. Algebra lineal. Grupo editorial iberoamericana. 2dª edición. México. 475 p. [ Links ]

Gulati, R. 1998. Alliances and networks. Strat. Manag. J. 19(4): 293-317. [ Links ]

Hodgson, G. 2007. La propuesta de la economía institucional. Economía Institucional y Evolutiva Contemporánea. Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Cuajimalpa-Xochimilco. México, D. F. 48-88 pp. [ Links ]

Hu, Y. 2006. Efficient, high-quality force-directed graph drawing. Mathem. J. 10(1):37-71. [ Links ]

INIFAP. 2011. Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias. Características botánicas, agronómica y de calidad del “arroz del estado de Morelos. México. Campo Experimental Zacatepec, Morelos. SAGARPA. Gobierno del estado de Morelos. 39 p. [ Links ]

IMPI. 2011. Solicitud de declaratoria de denominación de origen arroz del Estado de Morelos, México, Instituto Mexicano de la Propiedad Industrial/Gobierno del Estado de Morelos. [ Links ]

Izquierdo L. y Hanneman, R.2006). Introduction to the formal analysis of social networks using Mathematica, publicación digital, http://luis.izqui.org/resources.html. [ Links ]

López, S.; Barrón, D.; Corona, L. y Pérez, P. 2006. Políticas para la innovación en México. In: memoria del Vll Seminario de Territorio, Industria y Tecnología. Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa-Red de Investigación y Docencia en Innovación Tecnológica. Universidad Autónoma de Guanajuato. 210p. [ Links ]

Lozares, C. 1996. La teoría de redes sociales. Papers. 48:103- 126) <http://www.raco.cat/index.php/Papers/article/viewFile/25386/58613>. [ Links ]

LPI. 2010. Ley de Propiedad Industrial. Diario Oficial de la federación. http://edicion.unam.mx/pdf/LPinDUSTRIAL.pdf). [ Links ]

Lundvall, B. 1992. National systems of innovation: Toward a theory of innovation and interactive learning. Pinter Publisher, Londres. [ Links ]

Mizruchi, M. S. 1994. Social network analysis: recent achivements and current controversies. Acta Sociol. 37(4):48-90. [ Links ]

Martin, R. (2000). Institutional approaches in economic geography. In: Eric Sheppard y Trevor J. Barnes (eds.), A companion to economic geography, Oxford, Blackwell. 75-94 pp. [ Links ]

Moreno, J. 1934. Who shall survive?: Fundations sociometry, group psychotherapy and sociodrama, Nervous and metal disease publishing Co., Washington DC. [ Links ]

Nelson, R. R., and Sampat, B. N. 2001. Las instituciones como factor que regula el desempeño económico. Revista de Economía Institucional. 3(5):17-51. [ Links ]

Nelson, R. 1993. National innovation systems: a comparative analysis. Oxford university press. [ Links ]

Ostrom, E. and Ahn, T. K. 2003. Una perspectiva del capital social desde las ciencias sociales: capital social y acción colectiva. Revista Mexicana de Sociología. 65(1):155-233). [ Links ]

Pérez, C. (1992). Cambio técnico, restructuración competitiva y reforma institucional en los países en desarrollo. El trimestre económico, 59(233 (1): 23-64). [ Links ]

Pérez, C. 1983. Structural change and assimilation of new technologies in the economic and social systems. Futures. 15(5):357-375. [ Links ]

Porter, M. 1990. The competitive advantage of nations. Harvard business review. 68(2):73-93. [ Links ]

Rosales, E. y Gómez, R. 2010. La vinculación una estrategia de colaboración academia sector productivo. Caso de éxito, en Mesa de Trabajo 2: Redes de Colaboración Academia y Sector industrial: casos exitosos, presentado en el 5to congreso internacional de sistemas de innovación para la competitividad 2010: tecnologías convergentes para la competitividad. Universidad de Guanajuato, Campus Celaya, 1-20 pp. [ Links ]

Rosales, R. 2010. Aprendizaje colectivo, redes sociales e instituciones. Hacia una nueva geografía económica. In: los giros de la geografía humana: desafíos y horizontes. Lindón A. y D. Hiernaux. D. F., México. Antrophos/Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Iztapalapa. 123-142 pp. [ Links ]

SIAP. 2016. Base de datos del Sistema de información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera, http://www.siap.gob.mx/cierre-de-la-produccionagricola-por-cultivo/. [ Links ]

Tenorio, L. 2007. El mercado de trabajo de profesionistas y la vinculación de los sectores educativo, productivo y gubernamental. Análisis y propuestas para México. Redes. 1(1):145-170. [ Links ]

Tolentino, J. y Del Valle, M. 2014. El sistema agroalimentario local de arroz del estado de Morelos. Desarrollo y gobernanza territorial. UNAM- coordinación de humanidades. 65p. [ Links ]

Velázquez, A. y Aguilar, N. 2005. Manual introductorio al análisis de redes sociales, publicación digital, http://revista-redes.rediris.es/webredes/talleres/Manual_ARS.pdf. [ Links ]

Wasserman N. and Faust, K. 1994. Social networks analysis. Cambridge University press. Cambridge, UK. 755 p. [ Links ]

White, H. 1981. Where do markets come from? Am. J. Sociol. 87(3):517-547). [ Links ]

Received: March 01, 2017; Accepted: June 01, 2017

texto em

texto em