Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

versão impressa ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.6 no.8 Texcoco Nov./Dez. 2015

Articles

Energy and economic efficiency of maize in the buffer zone of the Biosphere Reserve "La Sepultura", Chiapas, Mexico

1Facultad de Ciencias Agronómicas-Universidad Autónoma de Chiapas. Carretera Ocozocoautla-Villaflores, km. 84.5. C. P. 30470 Villaflores, Chiapas. Tel: 965 6553272. (pinto_ruiz@yahoo.com.mx).

2Red de Estudios para el Desarrollo Rural, A. C., Avenida 5a Norte esquina 5a. Oriente 22, El Cerrito, Villacorzo, Chiapas. C. P. 30520.

3Maestría en Ciencias en Producción Agropecuaria Tropical, UNACH.

4Instituto de Investigaciones Agropecuarias "Jorge Dimitrov". Carretera vía a Manzanillo Bayamo, km 17.5. Granma, Cuba. C. P. 85100.

5Campo Experimental Pabellón-INIFAP. Carretera Aguascalientes-Zacatecas km 32.5. Pabellón de Arteaga, Aguascalientes, C. P. 20671.

Energy balance, production capacity of protein-energy and, economic feasibility of three maize production systems were studied: poly-culture maize intercropped with beans (SPM-1), production of landrace maize (SPM-2) and, production of improved maize (SPM-3), located in the ejido California within the Biosphere Reserve "La Sepultura" in the State of Chiapas, Mexico. Derived from a detailed description of production systems, analysis of energy inputs to the system, physical flows and inputs used to produce material (Meul et al., 2007) and analysis of energy efficiency (Funes, 2009) it was found that the production system of landrace maize intercropped with beans showed the highest energy efficiency with 1. 12 Mcal produced, compared to the systems of landrace maize in monoculture and improved maize, which had efficiency ratings of 1.07 and 0.99, respectively. Similarly, the SPM-1 showed the highest energy and protein, capable of meeting the requirements of9 and 23 individuals ha-1 year1, respectively potential. The biggest benefit/cost corresponded to the production system with improved varieties SPM-3. Among the energy and economic factors that increase the cost of production is high dependence on chemical inputs and the use of hired labour.

Keywords: Zea mays; food; energy balance; production systems

Se estudió el balance energético, la capacidad de producción de proteína-energía, y la factibilidad económica de tres sistemas de producción de maíz: policultivo maíz intercalado con frijol (SPM-1), producción de maíz criollo (SPM-2) y producción de maíz mejorado (SPM-3), ubicados en el ejido California dentro de la Reserva de la Biosfera "La Sepultura" en el estado de Chiapas, México. Derivado de una detallada descripción de los sistemas productivos, del análisis de ingresos de energía al sistema, flujos de materia física e insumos utilizados para la producción (Meul et al., 2007) y del análisis de la eficiencia energética (Funes, 2009), se encontró que el sistema de producción de maíz criollo intercalado con frijol mostró la mayor eficiencia energética con 1.12 Mcal producida, en comparación a los sistemas de maíz criollo en monocultivo y maíz mejorado, los cuales tuvieron índices de eficiencia de 1.07 y 0.99, respectivamente. De igual forma, el SPM-1 mostró el mayor potencial energético y proteico, capaz de satisfacer los requerimientos de 9 y 23 personas ha-1 año-1, respectivamente. El mayor beneficio/costo correspondió al sistema de producción con variedades mejoradas SPM-3. Entre los factores energéticos y económicos que más encarecen la producción, está la alta dependencia de insumos agroquímicos y el empleo de mano de obra contratada.

Palabras clave: Zea mays; alimentación humana; balance energético; sistemas de producción

Introduction

Maize is one of the species of highest importance in the human diet (National Commission for Good Agricultural Practice, 2008) and its use has spread to feed and biofuel production (Reyes, 1990; Ferraro, 2008).

In Mexico, maize production had an increase of 88% in the period 1980-2010, mainly due to progress in genetic improvement of the species and modern farming methods, with use of synthetic fertilizers, chemicals and machinery, as the surface sown only increased 3% (SIAP, 2012). Traditional methods make intensive use of labour and landrace seeds, while modern agriculture requires fossil energy input for production, fuel for the operation of machinery and electric power to pump water for irrigation (DeNoia and Montico, 2010) plus the energy consumed in the production of mineral fertilizers, insecticides and herbicides. Overall, agricultural systems requiring high current and growing amounts of inputs (DeNoia et al., 2006), which implies high energy costs.

In the Frailesca region, in the State of Chiapas, 88% of maize growers apply fertilizers and 76% use insecticides and herbicides (Aguilar, 2010), indicating high industrial energy spending in rural communities it contributes to the emission of greenhouse gases (GHGs) CEDECO (2006). Replacing traditional methods of production technologies for high industrial inputs cost more is evident (Vitta, 2001; Vilche et al., 2006).

It is known that the use of fertilizers and herbicides, together with the varieties and hybrids increase yields of agricultural systems (Bonel et al., 2005); however, it is required to estimate the energy balance, the production capacity of protein-energy and economic feasibility of the systems of production systems. In this case, the evaluation of energy efficiency helps explain the dynamics of power within the estate and the balance between the energy invested and energy produced (Pervanchon et al., 2002 and CEDECO, 2005).

Materials and methods

Study area

The research was conducted at the California community, municipality of Villaflores, Chiapas, in the buffer zone of the Biosphere Reserve "La Sepultura" (REBISE) 15'40.7'' between 16 ° north latitude and 93° 36' 42.9'' west longitude, with rainy weather is tropical, average temperature of 24 ° C, annual rainfall of 1023 mm, topography and soil type Regosol + Foezem + Cambisol (INEGI, 2012).

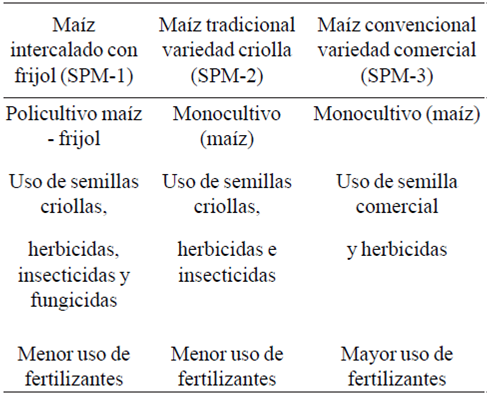

Production systems

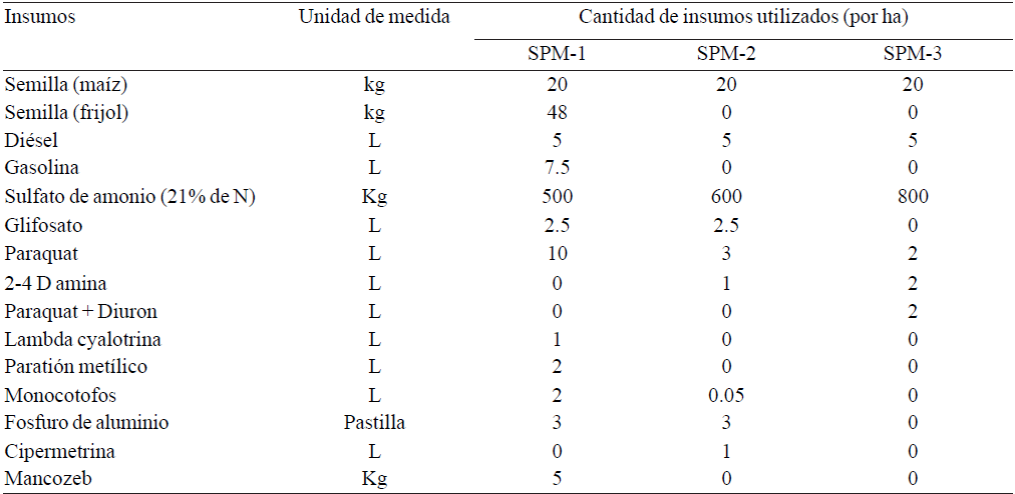

Maize intercropped with beans (SPM-1), landrace maize (SPM-2), improved maize (SPM-3), whose characteristics are presented in Table 1: Three production systems were evaluated.

Information analysis

An analysis on the systems approach, which involves the identification and characterization of system components maize production, inputs, outputs and relationships between components was performed (Guevara et al., 2011). To describe the work of each system, the proposed methodology used was by Geilfus (1997).

Energy balance

The analysis method described by Meul et al. (2007) was used, which considers the income of energy to the system, physical material flows and inputs used for production.

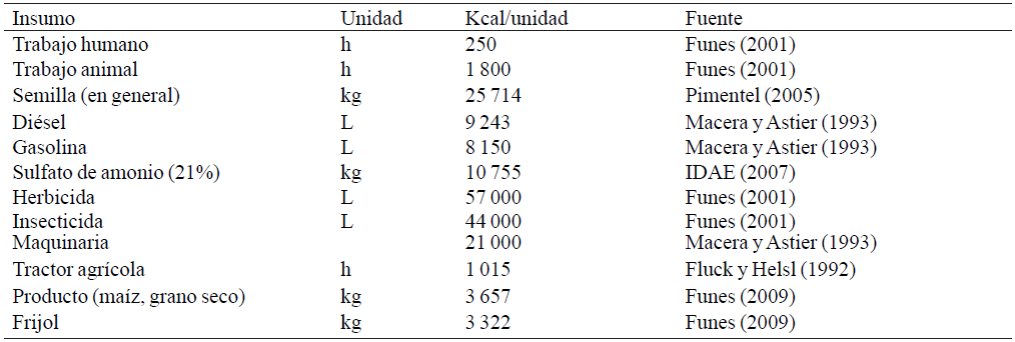

Based on the methodology by Funes (2009) energy efficiency was calculated using the variables: production system area, type and amount of food or products obtained direct or indirect energy costs of production, including human labour and animal, use of fuels, fertilizers and other inputs. Additionally the criteria set by Márquez et al. (2011) were used, who consider the direct and indirect energy used in production. The energy consumption was estimated using the methodology proposed by Bowers (1992). With the values of inputs and outputs, energy efficiency and the number of people who can feed, based on energy equivalence shown in Table 2 was calculated.

Direct and indirect sources of energy

According to Marquez et al. (2011), direct energy is that which is contained in the direct inputs such as fuel, electricity, fertilizer, pesticides, organic fertilizers and biological products, while indirect energy associated processes manufacturing, distribution and maintenance; for example, the need to obtain fuel from crude oil energy and required for the manufacture of pesticides and machinery, which is amortized over time.

Direct energy (Ed) Marquez et al. (2011)

a) Associated fuel consumption (Edc) Energy (Mcal / ha)

Where: Cc= fuel consumption (L/ha) Eeg= energy equivalent of oil (41 MJ / L)

b) Energy associated with labour employed (Edh) (MJ / ha)

Where: = energy equivalent of human labour (1.96 MJ/h for men and 1.57 MJ/h for women) (Mandal et al., 2002); nob= number of workers involved in a given task

Ctob= capacity work of agricultural workers (ha/h).

c) Energy associated with animals used in work (Eda) (MJ/ha)

Where: Ea= energy equivalent of the animal work (5.05 MJ/h) = number of animals involved in a particular task; = working capacity of animals (ha/h).

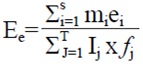

Energy efficiency

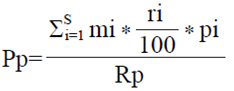

The following equation (Funes et al., 2011) was used to calculate the energy efficiency of production systems:

Where: Ee= energy sufficiency; S=number of products; m= amount of product (kg); e= energy content of the product (MJ/kg); T= number of inputs; I= input quantity (kg); f= energy required to produce an input (MJ / kg).

To calculate the energy produced and consumed the following formulas were used:

Where: EP= energy produced; EC= energy consumed; Production = yield (kg ha-1); Expenditure= spending inputs; EC= energy content as energy equivalence shown in Table 1 in Kcal/measurement unit.

Indicators on system productivity, as the amount of energy (MJ/ha/year) and protein (kg/ha/year) produced and further quantified correspondingly the number of people who could support the system according with average demand of one person per year of these nutrients (Funes et al., 2011). The energy and protein content for the calculations were taken from Gebhardt et al. (2007). Energy equivalence used for calculating the costs, direct and indirect inputs were those reported by Garcia-Trujillo (1996) and Funes et al. (2011).

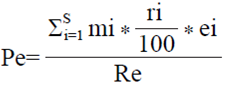

Where: Pe = people who sustain themselves on the basis of the energy produced; mi = production of each product (kg); ei = energy content of each product (MJ); A = area of the farm (ha); Re = energy requirement of a person (kg/ha).

To calculate the number of people that can be fed given protein requirements the following formula (Funes et al., 2011) was used:

Where: Pe = people who sustain themselves on the basis of the protein produced; mi = production of each product (kg); pi = protein content of each product (MJ); A = area of the farm (ha); Rp = protein requirement of a person (kg ha-1).

According to Funes (2001), the average energy consumption of a person is 1022 Mcal/year, while consumption of vegetable protein is 15.3 kg/year.

Results and discussion

Characteristics of maize production systems

At SPM-1 seeding of landrace maize variety known locally as "premature". We used 20 kg ha-1, obtained from the harvest of the previous cycle. Producers who plant make an average of 2 ha, with average yield of 2 t ha-1. The production is for home consumption, with 35% for household consumption and the rest for animal feed. The beans are grown during the period between the "bends" and the maize harvest, plant variety "white bean pod" at the rate of48 kg ha-1 seeds, with an average yield of 700 kg ha-1. Of the total production, 79% is sold and the rest is for consumption. The increased energy expenditure system from outside sources for the purchase of herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, fertilizers and fuel. The energy of human labour is provided by family labour and only in planting and fertilizer application as payment for the shelling of labour is required. The crop requires 125 ha-1 wages, of which 35% is paid.

In the SPM-2 are uses the early variety and 20 kg ha-1, also from the previous harvest. On average producers who use it, they sow 1 ha and produces about2250 kg ha-1. 55.5% of the production is sold and the rest is for consumption. Approximately, 13.5% of the grain used to feed animals, preferably backyard birds, the rest is for family consumption. The largest proportion of energy used enters the system through herbicides, insecticides and fertilizers use 103 ha-1 wages, of which 78 are covered with family work and the rest is hired.

In the SPM-3 is used on average 20 kg ha-1 of improved maize seed (commercial hybrids) varieties. It has been observed that these materials are susceptible to ear rot season of heavy rains, causing losses up to 50% of the crop. The maize plots are on average 3 ha. The average yield was 2600 kg ha-1. 100% of the production goes to marketing. Like the other two systems, the increased energy expenditure comes from external sources to acquire herbicides, fertilizers and fuel. Wages 104 ha-1 of which 30 are covered with hired work force are required. Table 3 shows the amounts of inputs used in the systems evaluated are shown.

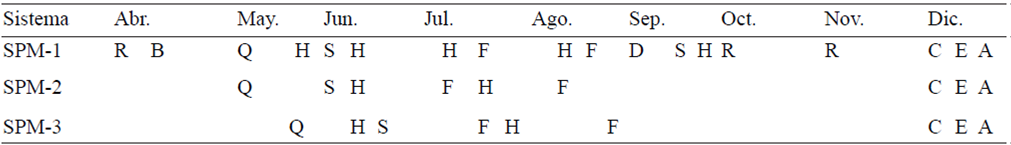

Description of the annual cycle of production systems

In general, the timing of agricultural activities in the three maize production systems is similar, except in the SPM-1, which has additional activities for bean management. During April and May the "rastrojeo" is performed (introduction of cattle on crop residues from the previous cycle), the construction of firebreaks gaps, burning and herbicide application is made. Maize planting takes place in June, when the rainy season starts. In all three systems, two applications of fertilizer are made during July and August. In systems monoculture maize herbicides applied during June and July and the SPM-1 system two additional applications for bean crops in August and September are made. The harvest takes place in December, but sometimes it is postponed until January or February next year (Table 4). Aguilar (2010), makes a similar disclosure for these systems.

Management labour

The length of the day and its cost depends on the type of work and its origin, whether family or hired. For example, when labour is needed, the maximum working time is 6 h-1 wages and wages paid $70-1, shelling maize in only about 1 h works full wage is paid when it is family labour, the producer gets to work up to 10 h-1 wages, and burning, the producer remains in the plot up to 24 hours to control the fire, according to the regulations of the National Commission of Natural Protected Areas (CONANP).

Energy balance

The SPM-1 and the SPM-2 had an energy efficiency higher than 1, indicating feasibility compared with SPM-3, which required more energy than that produced by the maize crop. In this regard, Funes et al. (2011) found that less diversified systems were less productive; therefore, although the production of a crop is smaller, diversification of the system makes energy more profitable. Moreover, energy efficiency SPM-3 (0.99) was very close to that obtained by Alemán and Brito (2003) in a system of maize in monoculture, with conventional methods of handling. However, if the results with studies Pimentel (1980) compared the three systems show low energy efficiency, since the average maize crop was 10 Mcal produced by Mcal inverted.

The energy balance is significantly affected by external inputs to maintain agricultural production (Valdés et al., 2009). When analysing energy intensity in the SPM-1 and the SPM-2 shows that to produce 1 kg of maize used Mcal 3.18 and 3.40, respectively. Both are dependent on fossil fuels and chemicals, and inefficient in the use of this energy source and are not sustainable in the long term, according to the findings of Pimentel and Pimentel (2005). The use of energy from chemicals, reported that more than 50% dependent on the contribution of the fertilizer ammonium sulfate (IDEA, 2007).

In production systems studied spend about 5377.5, 6453.0 and 8604.0 Mcal, contributing to obtain 0.37, 0.35 and 0.30 kg of maize, in each of the systems respectively. Moreover, the increased energy expenditure of inputs such as herbicides and insecticides in the SPM-1 is due to those required to control pests and diseases bean crop inputs. However, the energy contribution of this crop tends to offset these costs. For other inputs, such as the energy supply for fuel, there is little in the three systems, it only consumes shelling maize, by the use of machinery (tractor) and the sheller and in some cases, for moving crop.

Persons feasible for feeding

The increased production of energy and protein was for the SPM-1 (Table 5). From the energy point of view, the SPM-1 and SPM-3 systems produce enough energy to feed nine people ha-1 year-1, while the SPM-3 has a potential to feed eight people ha-1 year1. These results agree with the points made by Valdés et al. (2009) who argued that in energy terms in the various systems more efficiently produce the protein from both animal and vegetable origin.

Table 5 Energy balance and energy production potential and protein maize production systems studied.

Regarding the protein source, the higher capacity to meet the demands of human proteins was SPM-1 with 23 people ha-1 year-1, it includes beans, with which the system almost triple the protein content. For its part, the SPM-2 and SPM-3 systems have a capacity to feed 14 to 16 people ha-1 year-1, respectively. Schiere et al. (2002) reported that the number of people that can be fed with one hectare of monoculture (maize), is 10.4 on energy and protein sources 5.2 fountains.

Analysis of economic efficiency of production systems

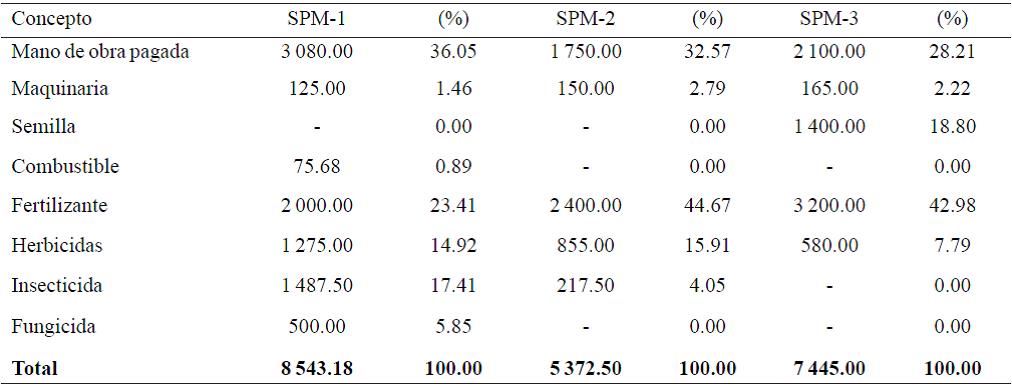

The total cost of the production system of maize associated with beans (SPM-1) was superior to the others (Table 6), mainly due to high prices of labour, although less than 25% invest in fertilizers, second largest item of expenditure in the three systems. A detailed cost analysis shows that the concept agrochemicals are leading to higher maize production systems in the studied community, with 61.6, 40.6 and 44.25% of the total cost of each system, respectively.

Table 6 Structure of economic expenditures (Mexican pesos) and percent of total in the three systems studied maize production.

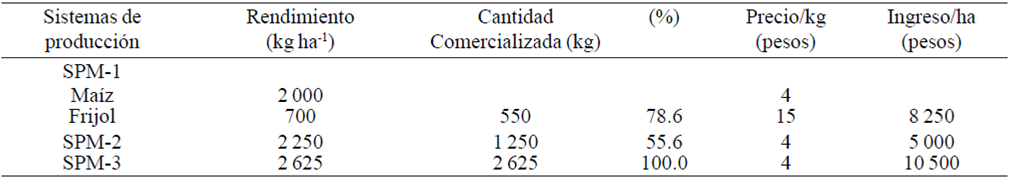

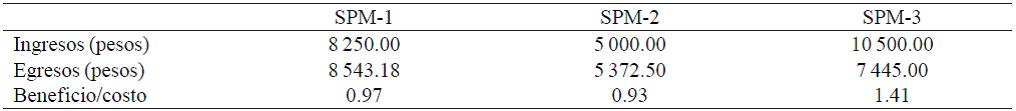

From the percentage of the marketed crop yields and selling prices of the products, SPM-3 is the one that brings higher income (Table 7). These results agree with those obtained by Miranda et al. (2008) who claimed that diversified systems have improved both financial and energy performance, which is partly consistent with the results achieved in this study. Considering the market only 50% of the crop of the SPM-1, this system would prove to be the most efficient from the economic point of view as it would allow incomes up to $ 12,500 ha-1, considering both crops.

The analysis of economic feasibility of the three production systems studied by calculating the cost benefit ratio (Table 8) shows that the SPM-3 is the most likely, with a profit of 41 cents for every peso invested.

Conclusions

The production system that combines maize-bean planting, using landrace seeds, is energy efficient, with 1.12 Mcal produced by each Mcal consumed, with regard to maize monoculture system, both as improved local varieties.

The maize-bean system was efficient in providing energy and protein for human consumption, to be able to feed 23 people ha-1 year-1, followed by monoculture system with the use of improved materials and system with landrace material.

The maize production system with the use of improved varieties was the most efficient from the economic point of view.

The concepts of costs, both energy and economic, that most affect maize production systems in the Biosphere Reserve "La Sepultura" are agrochemical inputs and payment of external labour.

Literatura citada

Aguilar, J. 2010. Informe final del estudio técnico: Validación de semilla y del proceso de mantenimiento de agro-ecosistema en los ejidos de California, Nueva Esperanza y Flores Magón localizados en la zona de amortiguamiento de la Reserva de la Biosfera la Sepultura, municipio de Villaflores, Chiapas. 73 p. [ Links ]

Alemán, P. R. y Brito, F. J. 2003. Balance energético en dos sistemas de producción de maíz en las condiciones de Cuba. Centro Agrícola. 30(3):84-87. [ Links ]

Bonel, B.; Montico, S.; Di Leo, N.; Denoia, J. y Vilche, M. 2005. Análisis energético de las unidades de tierra en una cuenca rural. Revista de la FAVE - Ciencias Agrarias. 4(1-2):37-47. [ Links ]

Bowers, W. 1992. Agricultural field equipment. Fluck, R. C. (Ed.). Energy in the world agriculture, energy in farm production. (6):117-129. [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional de Buenas Prácticas Agrícolas. 2008. Especificaciones técnicas de buenas prácticas agrícolas. Cultivo de maíz. Gobierno de Chile. Ministerio de Agricultura. 56 p. [ Links ]

CEDECO (Corporación Educativa para el Desarrollo Costarricense). 2005. Agricultura orgánica y gases con efecto invernadero. CEDECO. San José, Costa Rica. 27 p. [ Links ]

CEDECO (Corporación Educativa para el Desarrollo Costarricense). 2006. Emisión de gases con efecto invernadero y agricultura orgánica. CEDECO. San José, Costa Rica. 59 p. [ Links ]

Damián, H. M; Ramírez, V. B.; Aragón, G. A.; Huerta, L. M.; Sangerman, J. y Romero, A. 2010. Manejo del maíz en el estado de Tlaxcala, México: entre lo convencional y lo agroecológico. Rev. Latinoam. Rec. Nat. 6(2):67-76. [ Links ]

Denoia, J. y Monticos, S. 2010. Balance de energía en cultivos hortícolas a campo en Rosario (Santa Fe, Argentina). Ciencia, Docencia y Tecnología. 21(41):145-157. [ Links ]

Denoia, J.; Vilche, M.; Montico, S.; Bonel, B. y Di Leo, N. 2006. Análisis descriptivo de la evolución de los modelos tecnológicos difundidos en el Distrito Zavalla (Santa Fe) desde una perspectiva energética. Ciencia, Docencia y Tecnología. 17(33):211-226. [ Links ]

Ferraro, O. D. 2008. Evaluación energética de la producción de etanol en base a grano de maíz: un estudio de caso de la región Pampeana (Argentina). Ecología Austral. (18):323-336. [ Links ]

Funes, M. F. 2001. Sistema para el análisis de la eficiencia energética de fincas integrales. IIPF. Instituto de Investigación de Pastos y Forrajes. Cuba. [ Links ]

Funes, M. F. 2009. Agricultura con futuro, la alternativa agroecológica para Cuba. Estación Experimental Indio Hatuey, Universidad de Matanzas. 176 p. [ Links ]

Funes, M. F.; Suárez, J.; Blanco, D.; Reyes, F.; Cepero, L.; Rivero, J. L.; Rodríguez, E.; Savran, V.; del Valle, Y.; Cala, M.; Vigil, M.; Sotolongo, J. A.; Boillat, S. y Sánchez, J. E. 2011. Evaluación inicial de sistemas integrados para la producción de alimentos y energía en Cuba. Pastos y Forrajes. 34(4):445-462. [ Links ]

García-Trujillo, R. 1996. Los animales en los sistemas agroecológicos. ACAO. La Habana, Cuba. 100 p. [ Links ]

Gebhardt, S. E.; Lemar, L. E.; Pehrsson, P. R.; Exler, J.; Haytowitz, D. B.; Showell, B. A.; Nickle, M. S.; Thomas, R. G.; Patterson, K. K.; Bhagwat, S. A. y Holden, J. M. 2007. USDA national nutrient database for standard reference, release 23. http://www.ars.usda.gov/nutrientdata. [ Links ]

Geilfus, F. 1997. 80 Herramientas para el desarrollo participativo. Diagnóstico, Planificación Monitoreo y Evaluación. San José, C. R. IICA, 217 p. [ Links ]

Guevara, H. F.; Rodríguez, L. L.; Arias, L. M.; Gómez, C. H.; Fonseca, F. M.; Pinto, R. R.; Ponce, P. I.; Jonapá, M. F.; Carbonell, C. J.; Hernández, L. A.; Castillo, F. P. y Ovando, C. J. 2011. Metodología para el desarrollo de Procesos de Innovación Local a través de la Investigación Acción. Serie libros de texto: Núm.1. Ediciones Dimitrov. Bayamo, Granma. 27 p. [ Links ]

INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía). 2012. Anuario Estadístico de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos 2011/ Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. México. 155 p. [ Links ]

IDAE (Instituto para la Diversificación y Ahorro de la Energía). 2007. Ahorro, eficiencia energética y fertilización nitrogenada. IDAE. Madrid. 44 p. [ Links ]

Macera, O. y Astier, M. 1993. Energía y sistema alimentario en México: aportaciones de la agricultura alternativa. Agroecología y Desarrollo Agrícola en México, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana (UAM-X)- Xochimilco, México, D. F. [ Links ]

Mandal, K. G.; Saha, K. P.; Ghost, K. M.; Hati, K. M. y Bandyopadhyay, K. K. 2002. Bioenergy and economic analysis of soybean-based crop production systems in central India. Biomas and Energy. 23:337-345. [ Links ]

Márquez, M.; Valdés, N.; Ferro, M. E.; Paneque, I.; Rodríguez, Y.; Chirino, E.; Gómez, L. M. y Vargas, D. 2011. Análisis agroenergético de tipologías agrícolas en La Palma. Ríos, L. H.; Vargas, V. D. y Funes, M. F. (Comp.). Innovación agroecológica, adaptación y mitigación del cambio climático. Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Agrícolas (INCA), Cuba. 248 p. [ Links ]

Meul, M.; Nevens, F.; Reheul, D. and Hofman, G. 2007. Energy use efficiency of specialized dairy, arable and pig farms in Flanders. Agric. Ecos. Environ. 199:135-144. [ Links ]

Miranda, T.; Rey, M.; Hilda, M.; Julio, B. y Pedro, D. 2008. Valoración económica de bienes y servicios ambientales en dos ecosistemas de uso ganadero. Zootecnia Tropical. 26(3):1-3. [ Links ]

Pervanchon, F.; Bockstaller, C. ans Girardin, P. 2002. Assessment of energy use in arable farming systems by means of an agro-ecological indicator: the energy indicator. Agric. Syst. 72:149-172. [ Links ]

Pimentel, D. 1980. Handbook of energy utilization in agriculture. Boca Raton, CRC Press. [ Links ]

Pimentel, D. 2005. Environmental and economic costs of the application of pesticides primarily in the United States. Env. Dev. Sust. 7: 229-252. [ Links ]

Reyes, C. P. 1990. El maíz y su cultivo. Primera edición. Editorial AGT Editor. México D. F. 51 p. [ Links ]

Schiere, J. B.; Ibrahim, M. N. M. and Van Keulen, H. 2002. The role of livestock for sustainability in mixed farming: criteria and scenario studies under varying resource allocation. Agric. Ecosys. Environ. 90:139-153. [ Links ]

Valdés, N.; Pérez, D.; Márquez, M.; Angarica, L. y Vargas, D. 2009. Funcionamiento y balance energético en agroecosistemas de diversos cultivos tropicales. 30(2):36-42. [ Links ]

Vilche, S. M.; Denoia, J.; Montico, S.; Bonel, B. y Dileo, N. 2006. Uso de la energía en los sistemas agropecuarios del Distrito Zavalla (Santa Fe). Rev. Cient. Agrop. 10(1):7-19. [ Links ]

Vitta, J. 2001. La visión del desarrollo sustentable en el agro de nuestra región: bases para la discusión. Ambiental-UNR. 4(4):24:47. [ Links ]

Received: July 2015; Accepted: November 2015

texto em

texto em