Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Agricultura, sociedad y desarrollo

versión impresa ISSN 1870-5472

agric. soc. desarro vol.12 no.1 Texcoco ene./mar. 2015

Status quo, challenges and opportunities of alternative coffee that is produced in México and consumed in Germany

Status quo, desafíos y oportunidades para el café alternativo que se produce en México y se consume en Alemania

Claudia Bara1*, Pablo Pérez-Akaki2

1 Ciencias Ambientales (PMPCA), Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí. San Luis Potosí, S.L.P. 82000. (claudia.bara@yahoo.de) * Autor responsable.

2 FES Acatlán, UNAM. Alcanfores y San Juan Totoltepec SN, Santa Cruz Acatlán, Naucalpan, Estado de México. 53150. (ppablo@apolo.acatlan.unam.mx).

Recibido: febrero, 2014.

Aprobado: agosto, 2014.

Abstract

The objective of this study was to analyze the current markets for conventional coffee versus alternative coffee that is produced in México and consumed in Germany, and to identify opportunities and challenges in alternative – particularly organic and fair trade – coffee production, consumption and trade in and between the two countries. For this purpose, 18 interviews were conducted in México, with cooperatives or other organizations that promote and commercialize organic and/or fair trade coffee. The results show that the organic, fair trade and combined organic, fair trade production and certification system face too many challenges, such as social organization, administrative regulations, need for working capital, which must be overcome in order to benefit from these growing alternative markets in coffee consuming countries like Germany, where prices are better, social recognition exists, and consumer loyalty is constructed.

Key words: conventional coffee, organic, fair trade, commercialization.

Resumen

El objetivo de este estudio fue analizar los mercados actuales para café convencional versus café alternativo que se produce en México y se consume en Alemania, e identificar las oportunidades y los desafíos para la producción, el consumo y el comercio de café alternativo –particularmente orgánico y de comercio justo– en y entre los dos países. Con este fin, se realizaron 18 entrevistas en México, con cooperativas u otras organizaciones que promueven y comercializan el café orgánico y/o de comercio justo. Los resultados muestran que la producción y el sistema de certificación de café orgánico, de comercio justo y combinado orgánico-de comercio justo enfrentan demasiados desafíos, tales como la organización social, las regulaciones administrativas o la necesidad de capital para la operación, que deben sobre llevarse para poder beneficiarse de estos mercados alternativos crecientes en países consumidores de café como Alemania, donde los precios son mejores, existe reconocimiento social y se está construyendo lealtad por parte del consumidor.

Palabras clave: café convencional, orgánico, comercio justo, comercialización.

Introduction

México was, until 1989, one of the main coffee producing countries in the world; however, a number of factors have led to an overall stagnation in production in the last twenty years. The suspension of the International Coffee Agreement (ICA) and, thereby, the abolishment of the quota system led to a deregulation of the international coffee market in México similar to those in other coffee producing countries (Brown et al., 2010).

As a result, factors such as volatile coffee prices, low yields and higher production costs, non-existent post-harvest infrastructure, lack of access to basic services and migration, among others, have made it increasingly difficult for coffee growers in México to make a living from coffee and to benefit from the opportunities of an ever-changing demand sector (Calo and Wise, 2005). As an alternative way of survival, more and more Mexican coffee producers have sought out new opportunities in alternative niche markets, which allow them to commercialize their coffee at a reasonable price and thus to keep coffee production and commercialization as a means of subsistence.

Among these alternative coffees, often also referred as "sustainable coffees", there are organic and fair trade, but also Rainforest Alliance, Utz Kapeh Certified and 4C, among others3, which allow coffee producers to gain access to new consumer markets and claim to improve not only the quality of their product but also the economic, social and environmental impacts on their communities. These alternative coffees have proliferated in the last twenty years in México, and the share of producers adhering to alternative certification standards has increased as a consequence of the transformation of the coffee sector (Pérez Akaki, 2010a).

México is one of the major alternative coffee suppliers (Pierrot and Giovannuci, 2011), and Germany, is the main coffee consuming country in Europe. While in important consuming countries like Germany, with mature coffee markets, the conventional coffee market is not thriving, certified coffees such as organic and fair trade are emerging from simply a niche market, and they are receiving a premium in price (Pierrot and Giovannuci, 2011). Because of this premium, the price for organic and fair trade certified coffee in Germany is much higher than for conventional coffee. This is justified since a higher purchase price is paid to producers of alternative coffees.

Moreover, consumers' concerns about health, social justice and environmental issues have driven a growing market for organically produced and fairly traded products. Since Germany represents one of the most relevant import countries for Mexican alternative coffee, it is important to study the overall market context and more precisely the alternative (organic and fair trade) coffee segment in these two countries, in order to identify key trends, potentials and limitations in alternative production in México, consumption in Germany, and trade between the two countries.

The aim of this study was to analyze the current markets for conventional coffee versus alternative coffee that is produced in México and consumed in Germany. Also, to identify opportunities and challenges in alternative – particularly organic and fair trade – coffee production, consumption and trade in and between the two countries.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the methodology used to come to these results. Section 3 analyses the status quo of the coffee market in Germany, while Section 4 elaborates on the current situation of conventional and alternative coffee production and commercialization in México. Section 5 discusses the challenges and opportunities in alternative coffee production, consumption and trade found in this study; and Section 6 presents the conclusions.

Methods

The data collection method was based on semi-structured interviews used to identify the characteristics of coffee markets, to understand the ways that coffee chains are regulated along its nodes, and to recognize the main obstacles to trade by the different participants in the chain. The technique was used to collect qualitative data to contextualize the experiences of producers, to take into consideration the different views and perspectives of different actors, and to deepen the subject matter by the respondent (following essentially Hernández Sampieri, 1991). For that purpose, a semi-structured interview guide was prepared to be used with different actors (producers, certifiers, inspectors, etc.) according to the following indicators: production, certification, organization, commercialization, government policies, impacts and perspectives.

The interviews were performed with coffee producers from two different coffee producing areas in México: Pluma Hidalgo in the southwestern state of Oaxaca, and Xilitla in the central state of San Luis Potosí, in the Huasteca region. The information gathered locally served as snapshots of the current situation of conventional and alternative coffee producers in México. In addition to producers, qualitative interviews were carried out with experts and representatives of conventional as well as alternative coffee organizations and cooperatives such as UCIRI, CEPCO, CUCOS, an anonym producer organization in Xilitla, and with inspectors from agencies like CERTIMEX (Mexican certifier) and IMO Control (Swiss). In total, 18 interviews were conducted in México, of which 10 were with coffee producers4, 4 with representatives of certifying agencies, and 4 with coffee representatives from cooperatives or other organizations that promote and commercialize organic and/or fair trade coffee. Almost all interviews were conducted face to face with the interviewees, except for two of the interviews performed in México which were conducted via Skype (internet call). In Germany, little but valuable information was gathered by mail communication with one coffee consultant (previously managing director of a coffee roasting company), about key issues regarding organic-fair trade certified coffee trade between México and Germany.

Finally, a triangulation of information sources was used, based on primary data collection from the interviews and secondary data collection. The secondary data were based on literature, government data, published statistics, market research studies, and academic/research studies and reports complemented by case-studies at the micro-level.

Results

The coffee market in Germany

After the United States of America, Germany is the second largest importer of coffee, representing a share of almost 15 % in world imports (ITC, 2011a). Additionally, it is the largest importer in the European Union (accounting for 35 % of total EU green coffee imports). The total quantity imported in 2011 amounted to 1 168 674 tons, while 31% (356,663.68 tons) of total green coffee imports were directly re-exported, and about 18 % (205,870 tons) of green coffee imports were roasted and then re-exported (173 thousand tons of roasted coffee) to other EU countries like France, Austria, The Netherlands and Poland (CBI, 2012).

This reflects the presence of a large domestic roasting coffee industry in Germany, which not only roasts coffee for its own domestic needs but also in order to re-export to other countries (CBI, 2012). The most important suppliers of conventional coffee for Germany were Brazil and Vietnam, whose imports accounted for about 48.5 % in 2011. While Colombia has dropped from the third place in 2007 to the eleventh place in 2011, imported volumes from other countries like Peru (third place), Honduras, Ethiopia, Indonesia, India, Uganda, El Salvador and Papua New Guinea (listed in order of importance) increased their exports to Germany by 2011 (ITC, 2011b).

All big coffee players have their headquarters, or at least their affiliates, in Germany, most of which are located at the port of Hamburg, Europe's main entry point for coffee. The main players in the German coffee market are Kraft Foods (importer and roaster), Melitta (roaster), Tchibo (importer and roaster), Aldi (discounter), and Dalmayr (roaster). They control about 80 % of coffee roasting and sales. Due to the continuing consolidation of coffee companies, there is an oligopolistic buying power of mainstream roasters and retailers (TCC, 2012). At the end of the coffee supply chain, the coffee is delivered to wholesale/retail outlets or catering services as roasted coffee (beans or ground) and/or soluble (instant) coffee. Conversely to the concentrated roasting industry, there is a more competitive environment among wholesale traders and retailers. Nevertheless, like in other coffee consuming countries, there is a growing consolidation of coffee trade/roasting companies increasingly dominating the coffee sector in Germany (CBI, 2012).

As seen in Figure 1, overall green coffee consumption in Germany amounted to about 526 860 tons in 2010, remaining unchanged during the last couple of years; the per capita coffee consumption of an average of 6.4 kg (green coffee equivalent) also did between 2000 and 20105. These are equivalent to about 150 liters of coffee consumed per person per year, which is 23 % of the total EU market share, among the highest consumption amounts in the world (ECF, 2011; ICO, 2010).

With regard to alternative coffee, particularly certified organic-fair trade coffee, it has seen a substantial growth since the introduction of the organic (in 2001) and fair trade (in 1992) certification marks (BLE, 2010; Fairtrade Deutschland, 2011a). As seen in Figure 2, fair trade coffee sales, for instance, increased by 26 % from 2009 to 2010, out of which 67 % was also certified as organic coffee (Fairtrade Deutschland, 2011a).

The most important coffee suppliers of fair trade coffee to the German market are Perú, Colombia, México, Nicaragua, Brazil, Guatemala, Indonesia, Costa Rica and Ethiopia (Fairtrade Deutschland, 2011b). For organic coffee, the main suppliers are Perú, México, Honduras, Indonesia and Ethiopia (Pierrot and Giovannuci, 2011). In 2010, fair trade certified coffee imports amounted to 7,218 tons, of which about two-thirds are double-certified organic (Fairtrade Deutschland, 2011b). Overall organic coffee amounted to about 7620 tons (among which there may be also double certified organic-fair trade coffee), with slight decrease from 8400 tons in 2009. Both organic and fair trade coffees are on a constant increase since more and more coffee consumers demand that coffee companies participate in certified production (TCC, 2012).

Nonetheless, at present, the organic-fair trade coffee market represents about 5 % of the total coffee market; that is, it is still a niche market, although growing faster than the conventional coffee market (SIPPO and FIBL, 2011). Although the organic and fair trade product range has seen considerable growth in main retail shops and discounters, as well as in specialized retail stores (Hamm and Rippin, 2009), the low demand for alternative coffee might be a result of the considerable higher price that has to be paid for organic and/or fair trade certified coffee. For instance, the average retail price of roasted coffee in Germany was about 3.76 EUR/500 g (7.52 EUR/kilo) in 2009, among the lowest in the EU countries (ECF, 2011). About 500 g of organically certified Fairtrade coffee costs between 6 and 9 Euro. To illustrate the price composition of conventional coffee versus alternative coffee, the fair trade coffee Café Orgánico from the Fair Trade Company GEPA is given as an example and contrasted with the conventional coffee price composition of 3.70 EUR per 500 g. The end consumer price for 500 g of the organic-fair trade certified coffee (ground) is 7.38 Euro. The coffee is pure Arabica coffee and is sourced from México's highlands (GEPA, 2012) (Table 1). (cited in Die Zeit), 2011.

As is shown in Table 1, producer groups of alternative coffee receive three times more for their certified organic-fair trade coffee than conventional producers do; they receive about three times as much as conventional producers get for 500 g of roasted coffee (595 green coffee equivalents). However, in order to compare whether alternative producers are generally better off than conventional producers, it is necessary to also compare the cost structure of both: in the case of organic and fair trade certified coffee, producers have to bear additional certification and maintenance costs, demanding a quite long period for producers to recover their cost of conversion to organic production (Calo and Wise, 2005). The producer share of the end consumer price for alternative coffee is higher (20 %) than that of a conventional producer (13 %). About 1.20 Euro per 500 g go to the producer and an additional 0.31 Euro per 500 g is paid by the purchasing company to the producer cooperative, which includes the development and the organic premium, as well as farmers' payments. In total, the producer group in the producer country receives a 20 % value share of the final price that consumers pay in Germany for this certified organic-fair trade coffee.

Also, the price composition between conventional and certified organic-fair trade coffee is important in this comparison. As Figure 3 shows, one can see that about half of the value share from the conventional coffee end consumer price is split, in both cases, between traders/roasters and retailer (50% for conventional and 53 % for alternative coffee). However, in the end, what stands out particularly in both price calculations is that most of the value share – 87 % for conventional and 80 % for alternative coffee – is made outside the producer country, and the largest part of the added value remains in Germany. About 37 % (including excise duty and VAT) in the case of conventional coffee, and about 22 % in the case of alternative coffee, go into the German treasury.

This represents almost three times the share that producers of conventional coffee get, and in the case of alternative coffee, a slightly higher share of what alternative coffee producers get for their green coffee in México. Hence, although consumers pay almost twice as much for alternative coffee and producers benefit from the premium they get for certified organic-fair trade coffee in comparison to conventional coffee, a large share of the end consumer price is still retained in the consuming country Germany (Deutscher Kaffeeverband (cited in Die Zeit), 2011; GEPA, 2012).

The coffee market in México

Presently, coffee occupies the sixth place in terms of area cultivated in México (after corn, grass, sorghum, bean, fodder oats) with about 781 015 hectares of cultivated land (SIAP, 2010). Coffee is one of the main income sources of the primary sector in the national economy and accounted for 4.5 % of the agricultural value with regards to perennial crops, in 2009. In the southern states, about half of the economically-active population, of which around 65 % have an indigenous origin, work in the coffee sector and depend directly on coffee for their livelihood (Renard, 2010).

There are more than 504 372 coffee producers who generate coffee in the following 12 states in central and southern México (listed in order of importance): Chiapas, Veracruz, Oaxaca, Puebla, Guerrero, Hidalgo, San Luis Potosi, Nayarit, Jalisco, Tabasco, Colima, and Queretaro. The average production surface has decreased by almost half, from an average of 2.7 ha in 1992 to about 1.37 ha per producer in 2010 (Table 2).

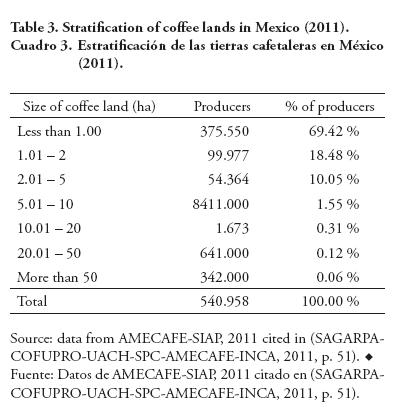

Thus, the number of small-holding producers has increased, while the average surface of the coffee plots has decreased significantly in several states of México. In fact, as shown in Table 2, of the total producers in the country about 98 % have less than 5 ha, about 88 % less than 2 ha, and almost 70 % have less than 1 ha of land. Small-scale producers with less than 1 ha of coffee land cover represent about 35 % of the total surface cultivated with coffee in México. On the other extreme, just about 2 % of the larger-scale coffee producers have more than 5 hectares of coffee land, but they cover almost 21% of total coffee land cultivated (Table 3).

This clearly shows that the land has been split up by inheritance among family members or that parts of the lands were sold because of the coffee crisis (SAGARPA-COFUPRO-UACH-SPC-AMECAFE-INCA, 2011).

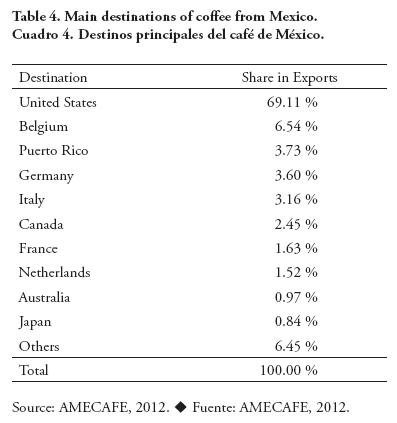

At the international level, México is currently the seventh largest producer of conventional coffee after Brazil, Vietnam, Colombia, Indonesia, India and Ethiopia, accounting for 3.2 % of total global production. Domestic production totaled 4.3 million bags on average in the 2011-2012 coffee cycle, of which approximately 40 % (2.6 million bags) was exported (FAS-USDA, 2011). In January 2012, coffee was exported to 39 countries of the five continents and the largest part (69.11 %) went to the United States (Table 4).

Just 1 % of total coffee exports was toasted and ground coffee, about 27 % of total coffee was exported for solubles and extracts, thus about 72 % were exported as green coffee (AMECAFE, 2012). México's average exports in the last decade accounted for more than 80 % of national coffee production (FAS-USDA 2002, 2005, 2011) and represented about 6.4 % of total agricultural exports (INEGI, 2012).

As seen in Table 5, total production and total exports of coffee from México has decreased considerably in the last 10 to 15 years, while coffee imports and domestic consumption seem to have increased considerably. According to SAGARPA, coffee consumption has increased to around 1.8 million 60-kg bags in 2011, representing an annual per capita consumption of an estimated 1.3 kilograms in comparison to about 0.4 to 0.5 kilograms per capita at the beginning of the century (SAGARPA, 2011).

The policy programs that were implemented after the dissolution of INMECAFE have been characterized by uncertainty and low continuity. Even though there has been a strategy of decentralization to enhance participation of regional governments, there still remains a strong dependency on central programs and resources. These programs were focused on providing technical and credit assistance rather than processing and commercialization support, directed towards ensuring the survival of small producers and compensating them in times of low prices, instead of creating a long-term national strategy (Pérez Grovas, 2001).

As consequence, processing and commercialization of coffee in México moved towards being dominated by big transnational coffee trading companies such as AMSA (ECOM Trading), Cafés California (Neumann Group), BECAFISA (VOLCAFE) and Nestlé. These transnational companies (TNCs) have enjoyed an empowerment in their role in coffee commercialization from México and their interests are protected by the national organism AMECAFE, more than those of the producers themselves (F. Villegas, personal communication, April 29, 2012). Moreover, these TNCs have the power to prevent the implementation of a national strategy and public policy measures that could bring the sector forward with regard to improving coffee quality and, hence, the access of producers to higher prices, as well as increasing internal consumption (CEPCO, 2011).

As a counter-movement, several grassroots organizations, cooperatives and other social enterprises arose, searching for alternative survival strategies, and they increasingly participated in alternative commercial trade schemes (Barrera and Vargas, 2011). As seen in Figure 4, several producers in the southern and, to a lesser extent, in the central coffee regions have specialized in production and trade of alternative (or differentiated) types of coffees such as organic and fair trade coffee. Hence, major states for organic coffee cultivation, in order of importance, are Chiapas, Oaxaca, Veracruz, Guerrero and Puebla (Pérez Akaki, 2010b).

Most producers who participate in organic and fair trade certification are organized in cooperatives, most of which are from indigenous communities. Well-known organizations in the organic coffee market that are also Fairtrade-certified are UCIRI6, Majomut7, La Selva8, Tosepan Titataniske9, among others. They have gained access to increasing alternative coffee consuming markets like the US and European countries where they have established contacts with diverse roaster clients.

Through the success of these organizations, organic coffee production and the participation in fair trade markets have grown considerably in the last couple of years: organic cultivation of coffee has increased significantly in the last decade, from about 70 838 ha in 2000, to 147 137 ha in 2004/2005 and 185 193 ha in 2007/2008. This represents an increase of about 260 % in organically managed coffee surfaces since 2000, an average annual growth rate of more than 37 %. While in 2000 organic coffee cultivation participated by about 10.4 % of the total coffee surface, in 2004/2005 it was already almost 19 % and in 2007/2008 almost 24 % (CIIDRI/CONACYT, 2008). Moreover, in 2007/2008 about half of the surface cultivated in México mainly with organic crops was dedicated to coffee, as shown in Figure 5 (CONACYT/UACH, 2009).

An important booster of the increase in surface of organic coffee cultivation since the end of quota system in 1989 was the relatively low and unstable coffee prices in the futures market. Hence, the price paid for organic-fair trade coffee was between 15 and 20 US dollars above the conventional coffee price at NY market.

Moreover, the interest in promoting organic production is mainly due to the external demand, which has influenced considerably the structure and the participation in organic certification of products such as coffee (Cruz, 2010). Certification is done in function of the number of producers in the group and the programs to which they want to adhere (EU, Japan, US) (T. R. Santiago, executive director CERTIMEX, personal communication, May 1, 2012). Today, there are twenty-one agencies involved in organic certification in México. With the exception of CERTIMEX10 (with its English definition: Mexican Certification Product and Ecological Processes), all of these agencies are based in foreign countries – 11 in the United States, 4 in Germany and the rest in Italy, Switzerland, Sweden and Guatemala. CERTIMEX certifies almost 26 % of the production units (74 % of organic production is certified by foreign certification agencies) (CONACYT/UACH, 2009: 65). The local certification agency has to pay each year an accreditation fee to international certification bodies to be accredited (T. R. Santiago, executive director CERTIMEX, personal communication, May 1, 2012).

Since 2006, the Mexican government's involvement in organic production has increased considerably, because of the implementation of the "Organic Products Law" (Ley de Productos Orgánicos) at the beginning of that year and the National Council for Organic Production (Consejo Nacional de Producción Orgánica) in 2007. However, since the Guidelines for Organic Operations11 was held for review by SAGARPA, the regulatory framework is not comprehensive and valid (Salcido, 2011).

Currently, about 44 coffee producer organizations (41 Arabica coffee producers, 2 producers of unspecified coffees and 1 Robusta coffee producer) and 14 trading organizations (13 of coffee Arabica and 1 of unspecified coffee) in México are fair trade certified and produce and commercialize coffee through fair trade channels (FLO-Cert GmbH, 2012). In the meantime, México has become the world's largest producer of organic coffee and was in 2009-2010, with 9,500 million tons, the world's third largest producer country of fair trade organic certifiable coffee (after Peru and Indonesia) (CIIDRI/CONACYT, 2008; Fairtrade International, 2011).

Challenges and opportunities found in alternative coffee production, consumption and trade

In the case of Germany, findings resulting from the literature review about alternative coffee consumption trends have shown that consumption of certified organic and fair trade coffee has seen an upward trend in the last couple of years. Nonetheless, although sales of organic as well as fair trade products are increasing, the following main obstacles and limitations have been identified from existing consumer behavior studies (B.G.W., 2011; Business Monitor International, 2010; Henseleit, 2011; German Coffee Association, 2011):

a) Low coffee prices for conventional coffee and a general lack of mainstream consumer awareness and information about coffee generate less competition in terms of consumption, compared to other drinks (Business Monitor International, 2010). Having the option to choose between organic/fair tade products and conventional products can represent an obstacle, since consumers are not informed enough and/or information for decision-making overwhelms people. Although there is an increasing consciousness among consumers, there is still little willingness to change consumption habits. Hence, there is a gap between good intentions and actual purchasing decisions which prevents alternative coffees from moving from the elite to the masses (B.G.W., 2011).

b) Generally, sustainable consumption requires more efforts and resources such as time, information and money. Since Germany has the cheapest groceries in Europe, there is a certain price-sensitivity among consumers and price-competition among producer companies that might beat down further the price for alternative products. With regard to organic-fair trade coffee – as shown in the coffee example in Table 1 – the price is almost double that of conventional coffee and the coffee tax makes alternative coffees even more expensive. This means that organic and fair trade certified coffee is less bought than other fair trade products (F. Niehoff, personal communication, July 31, 2012).

c) There is a glut of sustainable initiatives and labels in the German market that causes confusion among consumers. Simultaneously, double and triple certification, for example the EU-label, national Bio-label and private label standards for organic products (Naturland, Demeter, etc.), cause additional confusion. The more the market for alternative products is growing and becoming mainstream, the greater the risk that the trust is betrayed by anonymous structures or scandals in the industry. For instance, many companies create their own private label initiatives whose standards are sometimes lower (or above, e.g. Rapunzel, Hipp) than those third-party certification systems. Marketing activities try to benefit from the green movement and companies declare conventional products as organic and climate-friendly by using misleading labels on the market, something known as greenwashing (B.G.W., 2011). This represents a challenge for consumers to guide themselves in the sustainable product market (B.G.W., 2011), and an impediment for organic-fair trade certified coffee to reach the mainstream market. The commitment of several key players (like Kraft and Tchibo) to partly increase the share of sustainable coffees to 100% within the next decades shows that sustainable coffees represent a dynamic market segment in Germany (TCC, 2012).

When looking at the challenges found in the alternative coffee market in México, these go much beyond those that conventional producers face. Hence, when it comes to production, certification, organization and commercialization of coffee with organic and fair trade standards, alternative coffee farmers face, among others, various cross-cutting challenges:

a) Some constraints that the producers interviewed face in the production phase are briefly elucidated in the following: labor scarcity, small coffee plots (average 1.37 ha), low productivity, aging coffee trees, limited post-harvest infrastructure, lack of comprehensive policy measures, inadequate support programs and low institutional participation to support organic production.

b) Coffee producers have to deal with numerous certification requirements and high costs in order to obtain and maintain the organic and fair trade certification. The organic certification process takes up to three years during which producers have less income, higher costs (including certification costs) and (in some cases) less productivity. As Villegas, a conventional coffee producer in Oaxaca, puts it: "the transition process to organic represents a poverty trap for producers who want to enter organic production" and "organic coffee is the way from poverty into misery, since productivity is low and organic producers do not live better from selling organic coffee" (Villegas, personal communication, April 29, 2012). The fair trade certification costs for producer organizations, and hence producers, were reported to rise each year and are higher than just organic. Since many cooperatives are organic and fair trade certified, they have to undergo double certification processes by two different certification bodies, for instance, FLO-Cert and CERTIMEX for "organic-fair trade" certification. As certification processes and certification requirements get more stringent, producers face more and more challenges to adopt and maintain certification. J. Celis, an organic inspector for CERTIMEX, puts it this way: "FLO is not working well anymore for México; those who were certified go on, but it has become more difficult for new entrants to get double certification" (J. Celis, personal communication, May 2, 2012).

c) There is a general mistrust in the benefits of certification since certification standards depend on production and trade rules set by certification agencies from the North. Moreover, Fairtrade USA even decided in January 2012 to leave the fair trade umbrella organization – Fairtrade International – since it wanted to promote the certification of large plantations and to make it easier for large corporations to enter the fair trade market (FLO-CERT, 2012). Small-scale producers and cooperatives now fear that they might lose market access and that "larger coffee plantations will put them out of business" (Hill, 2012).

d) Small-scale coffee growers cannot survive in international markets unless they are organized to reach economies of scale and to access higher priced markets. However, some of the problems and criticism that producer organizations face are related to weak farmer organization; failure to provide basic services; mistrust in organizational management and lack of transparency; lack of consistency and continuity in meeting certification standards and in the commitment with the organization; and, limited volume and commercial contacts. This was acknowledged by many of the producers interviewed.

Despite all these challenges, there are many advantages and opportunities to be found for Mexican coffee producers in the alternative coffee market. Some of these potentials are linked to an increasing international market demand for alternative (specialty) coffee and strong consumption patterns, and increasing awareness for alternative and innocuous products in main importing countries and some emerging ones. Moreover, there is a great potential to develop the national consumption market for quality and alternative coffees as it is growing in the capital city of México and in some coffee growing regions like Oaxaca and Chiapas.

When analyzing the trade patterns between México and Germany, México is at the forefront of the countries that export alternative coffee to main coffee consuming countries, and Germany is one of the most important buyers of these kinds of coffees from México. The fact that CERTIMEX was accredited in 2003 as a certification agency by the German agency Deutsches Akkeditierungssystem Prüfwesen (DAP) (today Deutschen Akkreditierungsstelle GmbH (DAkkS) facilitates the entrance of Mexican organic producers (that were certified by CERTIMEX) to the German market. The DAP verified that certification issued by CERTIMEX meets the demands of the country's organic products. In 2011, CERTIMEX went one step further when it obtained the official approval for imports of organic products in the EU under EC Regulation No. 1267/201112. Hence, CERTIMEX is currently the only accredited Mexican certification agency that has the right to certify producers directly and that is recognized by European Union's organic importers. As the director of CERTIMEX, Taurino Reyes Santiago, stated in a personal interview: "this facilitates access to the EU market and CERTIMEX has received confidence from international buyers, through accreditation" (T. R. Santiago, personal communication, May 1, 2012).

However, with regard to alternative coffee trade with Germany, Hernández Balderas from CEPCO stated that other importing countries like the US offer better market conditions than Germany, since they pay a higher price differential, have more demand, less quality requirements and a closer geographical location (H. Balderas, personal communication, May 5, 2012). Moreover, according to R. Santiago, there is increasing bureaucracy for certification according to stringent law requirements and import permits that hamper the export of alternative coffee from México to Germany (R. Santiago, personal communication, May 1, 2012).

When it comes to selling certified coffee in Germany, fair trade certified coffee is sold either through fair traders or through conventional sales channels (such as the discounter chain Lidl). This is seen with large criticism, since there is still a huge distance between producer and consumer in the fair trade supply system and similarities to the conventional supply channel are more and more visible. The decision of Fairtrade to allow big companies to enter this market has openly been criticized, since companies can get the fair trade label regardless of the percentage of products that they sell under fair trade conditions or their general (unethical) business practices. As discussed in the previous section, many companies just engage in organic-fair trade to greenwash their image.

The potential to directly process the coffee in the producing country and then export it as toasted and ground coffee is restricted, since the import tax for processed coffee is much higher than that of green coffee. Additionally, the roasting and the coffee compositions/blends have to be adapted according to different consuming markets, whose coffee tastes differ in different countries. Moreover, this would represent a problem with regard to coffee blends since they are composed of coffees from different origins (GEPA, 2012), avoiding dependence on specific places of origin, and they are also part of the intellectual property of roasters in the consuming places.

Nonetheless, alternative coffees are considered a viable alternative for Mexican coffee producers to compete with other supplier countries for market share in Germany. As emphasized by Niehoff, former managing director of a roasting company and current consultant in the coffee industry in Germany, producers who can sell their certified coffee through organized sales channels have a good advantage over conventional suppliers. However, according to him, the low supply reliability of cooperatives, the communication difficulties with small farmers, as well as the little offer of alternative coffee for the lower price range from México, still represent weaknesses in this country's coffee commercialization. Moreover, it is important that there is a close relationship between supplier and buyer, "since a trusting relationship helps to eliminate problems" (Niehoff, mail communication, July 31, 2012). Hence, L. M. Villanueva, a technical consultant for certification and commercialization at the best-known Mexican coffee cooperative UCIRI, acknowledged: "a direct relation and cooperation with buyers in Germany who speak the producer's language facilitates the trust between producers and buyers" (Villanueva, personal communication, May 23, 2012).

Implications of alternative coffee trade for Mexican producers

Coffee is a very important agricultural product for millions of people around the world, and more than 2 million people in México depend on it. Thus, any improvement in the commodity chain benefitting the producers can have huge impacts on indigenous, poor producers in isolated regions of the country (Pérez Akaki, 2010b). Consequently, it is necessary to foster research studies about the many ways that coffee producers in México can engage in better forms of trade.

The route towards alternative coffee production, consumption and trade is accompanied by complexity, contradiction, discrepancy and uncertainty. That's why we can say that there are many challenges that have to be overcome in both markets in order to promote the fair trade between the two countries of organically produced coffee.

Although alternative coffee consumption in Germany is still quite low, it is a market with great potential, which is growing faster than the conventional coffee market (Pierrot and Giovannuci, 2011). Moreover, the overall growing organic and fair trade market clearly offers a positive environment for its expansion. However, there is a need for more promotional activities to increase the consciousness for quality, organically grown and fairly traded coffee among general coffee consumers in Germany, in order to move the trend from cheap coffee towards more quality and sustainable coffee consumption.

On the Mexican side, there is a strong need for better organization, starting with the public sector, which has to establish clear rules of the game in the coffee sector and carefully design programs that have to be implemented in order to promote the participation and organization of producers in the alternative coffee sector. We can say that there is much opportunity at this moment to promote the alternative coffee sector, but several aspects have to be taken into consideration:

a) Alternative markets can be potentially beneficial for producers, but transparency and quality are always important factors considered by organic production and fair trade certification systems. Any mistake in communication, lowering in quality standards or unclear operation could signify an expulsion from the market (González Cabañas, 2002).

b) Consumers (and retailers) are continuously looking for an increase in quality standards, both in the conventional and alternative markets.

c) A changing demand means that participation in alternative markets requires considerable changes and continuous improvements, not only in agricultural production, but also in administrative processes, trade patterns and commercial strategies.

d) New concerns in demands for compliance and supply chain traceability continuously appear. Moreover, recent worries about climate change and the environmental impacts of the coffee sector are forcing changes in agricultural practices and processing activities (Chávez-Arce, 2009).

e) Producers should never rely completely on one consumer market, but diversify their commercial channels, since that is what empowers them. Overconfidence in the alternative market can lead to bad experiences as is the case in conventional markets.

According to these concerns, it is also important to question the limits and the possible expansion of alternative markets in the future, as well as the evolution of these systems, especially with respect to the premium that is paid. As some studies show, the price premium for alternative coffee is increasing in correlation with quality measures taken, since more and more producers are certified and more distributors, brand owners and traders seem to demand higher coffee standards (Bacon, 2005; Pay, 2009). Nevertheless, it is difficult for producers to improve their quality since they have limited (access to) financial resources and, hence, low capacity to invest in their plantations. Indeed, important questions for future research are: whether the organic and fair trade market is big enough to accept more and more producers entering the market; under which conditions small-scale producers are able to participate and benefit from growing alternative markets; and whether the increasing participation of conventional coffee chain actors and powerful corporate participants in alternative markets are reabsorbing the potential and benefits that these alternative markets represent to small-scale producers, by dominant conventional market logics.

Conclusions

There are many opportunities for Mexican coffee producers in alternative markets, especially in coffee consumer markets like Germany, where alternative coffee demand is growing. Nevertheless, the challenges for Mexican producers to participate in alternative coffee trade with Europe surpass the benefits they can derive out of this activity. Unless they are well organized, enhance coffee quality and establish long-term relationships with buyers in Germany, they cannot improve their economic and social conditions in the long term. Moreover, it is not just about producers and actors in the coffee chain who need to make improvements, but rather that public policies may have a role to play in providing market incentives that promote participation of small-scale producers in organic production and fair trade, thus ensuring that alternative coffee production and trade maximizes the economic, social and environmental development impact in the Mexican coffee sector.

References

AMECAFE. 2012. Exportaciones Mensuales "Enero 2012". Retrieved 06-05-2012, from Asociación Mexicana de la Cadena Productiva del Café A.C.: http://amecafe.org.mx/downloads/Exportaciones%20mensuales%20enero2012.pdf, 2012 [ Links ]

Bacon, C. 2005. Confronting the coffee crisis: can fair trade, organic and specialty coffee reduce small-scale farmer vulnerability in northern Nicaragua? World Development 33(3): 497-511. [ Links ]

B.G.W. 2011. 3. Otto Group Trenstudie 2011 - Verbrauchervertrauen. Retrieved 03-28-2012, from Trendbüro Beratungsunternehmen für gesellschaftlichn Wand (B.G.W.) on behalf of Otto Group (ed): http://www.ottogroup.com. [ Links ]

Barrera, A., and M. Vargas. 2011. México remplaza arbustos de café para aumentar production. Retrieved 06-03-2011, from Inforural: http://www.inforural.com.mx. [ Links ]

BLE. 2010. The National Bio-Siegel. Retrieved 03-18-2012, from Federal Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection (Bundesministerium für Verbraucherschutz, Ernährung und Landwirtschaft, BLE): http://www.bio-siegel.de/english/basics/the-national-bio-siegel/. [ Links ]

Brown, O., C. Charveriat, and D. Eagleton. 2006. The Coffee Market - a Background Study. Oxfam: International Commodity Research – Coffee. pp: 1-12. [ Links ]

Business Monitor International. 2010. Germany - Food & Drink Report Q4 2010. Retrieved 07-25-2012, from Washington University Libraries: http://wulibraries.typepad.com. [ Links ]

Calo, M., and T. Wise. 2005. Revaluing Peasant Coffee Production: Organic and Fair Trade Markets in México. Global Development and Enivonment Institute, Tufts University. [ Links ]

CBI. 2012. Coffee in Germany. Retrieved 02-28-2012, from Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands: http://www.cbi.eu/marketinfo/cbi/docs/coffee_germany. [ Links ]

CEPCO. 2011. XI CONGRESO de la Coordinadora Estatal de Productores de Café de Oaxaca, A.C. Oaxaca: Coordinadora Estatal de Productores de Café de Oaxaca, A.C. [ Links ]

Chávez-Arce, V. J. 2009. Measuring and managing the Environmental Cost of Coffee Production in Latin America. Conservation and Society 7(2): 141-144. [ Links ]

CIIDRI/CONACYT. 2008. Agricultura Orgánica de México. [ Links ]

CONACYT/UACH. 2009. Agricultura, Apicultura y Ganadería Orgánicas de México - 2009; Estado actual - Retos - Tendencias. Chapingo: Universidad de Chapingo. [ Links ]

Cruz, M. A. 2010. Situation and challenges of the Mexican Organic Sector. 593-608. [ Links ]

Deutscher Kaffeeverband (cited in Die Zeit). 2011. Kaffeepreis: Zusammensetzung. Retrieved 03-06-2012, from Die Zeit, numbers cited from Deutscher Kaffeeverband: http://images.zeit.de. [ Links ]

ECF. 2011. European Coffee Report 2010/2011. Retrieved 04-28-2011, from European Coffee Federation (ECF): http://www.ecf-coffee.org/images/stories/European_Coffee_Report_2009.pdf. 30 p. [ Links ]

Fairtrade Deutschland. 2011a. Fairtrade bewegt - TransFair-Jahresbericht 2010/2011. Retrieved 01-18-2012, from TransFair - Fairtrade Deutschland: http://www.fairtrade-deutschland.de. [ Links ]

Fairtrade Deutschland. 2011b. Product-Fact Sheet "Kaffee". Retrieved 03-15-2012, from Fairtrade Deutschland: http://www.fairtrade-deutschland.de. [ Links ]

Fairtrade International. 2011. National Fairtrade organizations. Retrieved 03-20-2012, from Fairtrade International: http://www.fairtrade.net/labelling_initiatives1.html. [ Links ]

FAS-USDA. 2002. Coffee Analysis: World Coffee Consumption By Importing Country. Retrieved 05-20-2012, from United States Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service: http://www.fas.usda.gov. [ Links ]

FAS-USDA. 2005. Coffee Analysis: World Coffee Consumption By Importing Country. Retrieved 05-20-2012, from United States Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service: http://www.fas.usda.gov. [ Links ]

FAS-USDA. 2011. Coffee Analysis: World Markets and Trade. Retrieved 02-10-2012, from United Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service: http://www.fas.usda.gov. [ Links ]

FLO-Cert GmbH. 2012. FLO-Cert Operators. Retrieved 03-29-2012, from FLO-Cert GmbH: http://www.flo-cert.net. [ Links ]

FLO-CERT. 2012. Implications for Certification - Fair Trade USA is no longer a member of Fairtrade International. Retrieved 07-02-2012, from FLO-CERT GmbH: http://www.flo-cert.net. [ Links ]

GEPA. 2012. Warum hat die GEPA das Fairtrade-Siegel von vielen Produkten heruntergenommen? Retrieved 07-23-2012, from GEPA The Fair Trade Company: http://www.gepa.de. [ Links ]

German Coffee Association. 2011. Deutscher Kaffeemarkt 2010 im Umbruch. Retrieved 02-29-2012, from Deutscher Kaffeeverband, Pressemitteilung: http://www.kaffeeverband.de. [ Links ]

González Cabañas, A. A.. 2002. Evaluation of the current and potential poverty alleviation benefits of participation in the Fair Trade market: The case of Unión La Selva, Chiapas, México. Research report. [ Links ]

Hamm, U., and M. Rippin. 2009. Germany - Market data 2000 - 2008. Retrieved 03-30-2012, from Survey by Kassel University and Agromilagro Research. Published at the Organic World homepage: http://www.organic-world.net. [ Links ]

Henseleit, H. 2011. Die Nachfrage nach Fair-Trade-Produkten in Deutschland - Eine empirische Untersuchung unter Berücksichtigung von Präferenzen für Bio-Produkte. Retrieved 03-18-2012, from GEWISOLA: http://ageconsearch.umn.edu. [ Links ]

Hernández Sampieri, R. 1991. Metodología de la investigación. México, D.F. McGraw-Hill Interamericana Editores S.A. de C.V. [ Links ]

Hill, C. 2012. Fair Trade USA's Coffee Policy Comes Under Fire. Retrieved 07-06-2012, from http://www.eastbayexpress.com. [ Links ]

ICO. 2010. International coffee figures. Retrieved from International Coffee Organization. [ Links ]

INEGI. 2012. Estadísticas del comercio exterior de México. Retrieved 06-01-2012, from [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Geografía: http://www.inegi.org.mx/prod_serv/contenidos/espanol/bvinegi/productos/continuas/economicas/exterior/mensual/ece/ecem.pdf.

ITC. 2011a. Trade Map - International Trade Statistics; List of supplying markets for a product imported by Germany. Retrieved 05-02-2012, from International Trade Centre: http://www.trademap.org/Country_SelProductCountry_TS.aspx. [ Links ]

ITC. 2011b. Trade Map - Trade statistics for international business development; List of importers for the selected product in 2010 - 0901 Product: Coffee. Retrieved 03-08-2012, from International Trade Center: http://www.trademap.org/Country_Sel Product.aspx. [ Links ]

Pay, E. 2009. The market for organic and fair-trade coffee. Study prepared in the framework of FAO project GCP/RAF/404/GER. FAO, Rome. [ Links ]

Pérez Akaki, P. 2010a. Los pequeños productores de la región Otomí-Tepehua, su problemática y sus alternativas. FES Acatlán, UNAM, México. [ Links ]

Pérez Akaki, P. 2010b. Los espacios cafeteleros alternativos en México en los primeros anos del siglo XXI. Investigaciones Geográficas, UNAM. Boletín del Instituto de Geografía Núm. 72: 82-100. [ Links ]

Pérez Grovas. 2001. Case Study of the Coffee Sector in México. Retrieved 08-26-2011, from Markettradefair.com: http://www.maketradefair.com. [ Links ]

Pierrot, J., and D. Giovannuci. 2011. Sustainable Coffee Report: Statistics on the main coffee certifications. Retrieved 03-03-2012, from International Trade Center: http://www.intracen.org/Trends-in-the-trade-of-certified-coffees/. [ Links ]

Renard. 2010. The Mexican Coffee Crisis. Latin American Perspectives 37(21). [ Links ]

SAGARPA. 2011. Premian calidad de café; Aumenta su consumo per cápita en México. Retrieved 06-04-2012, from Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganaderia, Desarollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación, Boletin: http://www.sagarpa.gob.mx. [ Links ]

SAGARPA-COFUPRO-UACH-SPC-AMECAFE-INCA. 2011. Plan de Innovación en la Cafeticultura de México, Estrategia de Innovacion hacia la competitividad en la cafeticultura. Retrieved 06-03-2012, from Asociacion Mexicana de la Cadena Productiva del Cafe: http://www.amecafe.org.mx. [ Links ]

Salcido, V. 2011. Organic Foods Find Growing Niche in México. Retrieved 06-29-2012, from USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, Global Agricultural Information Network: http://gain.fas.usda.gov. [ Links ]

SIAP. 2010. Producción Agricola, Ciclo: Ciclicos y Perennes. Retrieved 06-02-2012, from Servicio de Informacion Agroalimentaria y Pesquera: http://www.siap.gob.mx. [ Links ]

SIPPO and FIBL.2011. The Organic Market in Europe. Retrieved 03-16-2012, from Swiss Import Promotion Programme (SIPPO) and Forschungsinstitut für biologischen Anbau (FIBL): https://www.fibl-shop.org. [ Links ]

Sistema Producto Café. 2011. Situación y perspectivas. Retrieved 06-01-2012, from Sistema Producto Café: http://www.spcafe.org.mx. [ Links ]

TCC. 2012. Coffee Barometer 2012. Retrieved 03-04-2012, from Tropical Commodity Coalition for sustainable Tea Coffee Cocoa, The Hague: http://www.teacoffeecocoa.org/tcc/Publications/Our-publications. [ Links ]

3 These last certification schemes are not relevant to this study. • Estos últimos esquemas de certificación no son relevantes para este estudio.

4 Of the 10 producers, two producers were already organically certified, four were in transition (the first or second year) to organic, two with natural (traditional) management and another two with conventional management. • De los 10 productores, dos productores ya tenían certificación orgánica, cuatro estaban en transición (primer o segundo año) para la orgánica, dos con manejo natural (tradicional) y otros dos con manejo convencional.

5 The difference of the coffee quantity imported and consumed is due to the fact that more than half of the coffee imported is again re-exported to the US and other European countries. • La diferencia de la cantidad de café importada y consumida se debe al hecho de que más de la mitad del café importado se exporta nuevamente a EUA y a otros países europeos.

6 Unión de Comunidades Indígenas de la Región del Istmo, Oaxaca. • Unión de Comunidades Indígenas de la Región del Istmo, Oaxaca.

7 Unión de Ejidos y Comunidades Cafeticultores Beneficio Majomut de R.I.C.V., Chiapas. • Unión de Ejidos y Comunidades Cafeticultores Beneficio Majomut de R.I.C.V., Chiapas.

8 Unión de la Selva, Chiapas. • Unión de la Selva, Chiapas.

9 Unión de Cooperativas Tosepan, Puebla. • Unión de Cooperativas Tosepan, Puebla.

10 CERTIMEX (Certificadora Mexicana de Productos y Procesos Ecológicos, Mexican Certifier of Ecologic Products and Processes) is the first and only local certifying agency in México. • CERTIMEX (Certificadora Mexicana de Productos y Procesos Ecológicos) es la primera y única agencia certificadora local en México.

11 "The Guidelines for Organic Operation" will provide the legal framework and standardization for organic production and commercialization in México, including the establishment of labeling requirements for organic products, among several other important policies related to the organic sector. • "Los lineamientos para la operación orgánica" proporcionarán el marco legal y la estandarización para la producción y la comercialización orgánica en México, incluyendo el establecimiento de requerimientos de etiquetado para productos orgánicos, entre muchas otras políticas importantes relacionadas con el sector orgánico.

12 Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No. 1267/2011 amending Regulation (EC) No. 1235/2008 laying down detailed rules for implementation of Council Regulation (EC) No. 834/2007 as regards to the arrangements for imports of organic products from third countries. • Reglamento de Implementación de la Comisión (UE) No. 1267/2011 que modifica el Reglamento (EC) No. 1235/2008 estableciendo reglas detalladas para la implementación del Reglamento del Consejo (EC) No. 834/2007 en lo que se refiere a los arreglos para las importaciones de productos orgánicos de países terceros.

13 Natural means organically-managed coffee plantation but without organic certification. • Natural significa una plantación manejada orgánicamente pero sin certificación orgánica.