Introduction

Asparagaceae is the most diverse family of Asparagales. It includes 153 genera and 2,290-2,650 species distributed worldwide except in the Arctic (APG IV, 2016; Bogler et al., 2006; Pires et al., 2006). Chase et al. (2009) divided Asparagaceae into 7 subfamilies: Agavoideae, Aphyllanthoideae, Asparagoideae, Brodiaeoideae, Lomandroideae, Nolinoideae, and Scilloideae. This classification was further supported by a phylogenetic analysis based on DNA sequences from 4 plastid genes (Chen et al., 2013). Agavoideae has 30 genera with petaloid flowers and rosulate leaves (McKain et al., 2016). The genera Agave L. sensu stricto, Manfreda Salisb., Polianthes L., Yucca L. and Echeandia Ortega diversified in North America (Jiménez-Barron et al., 2020; McKain et al., 2016).

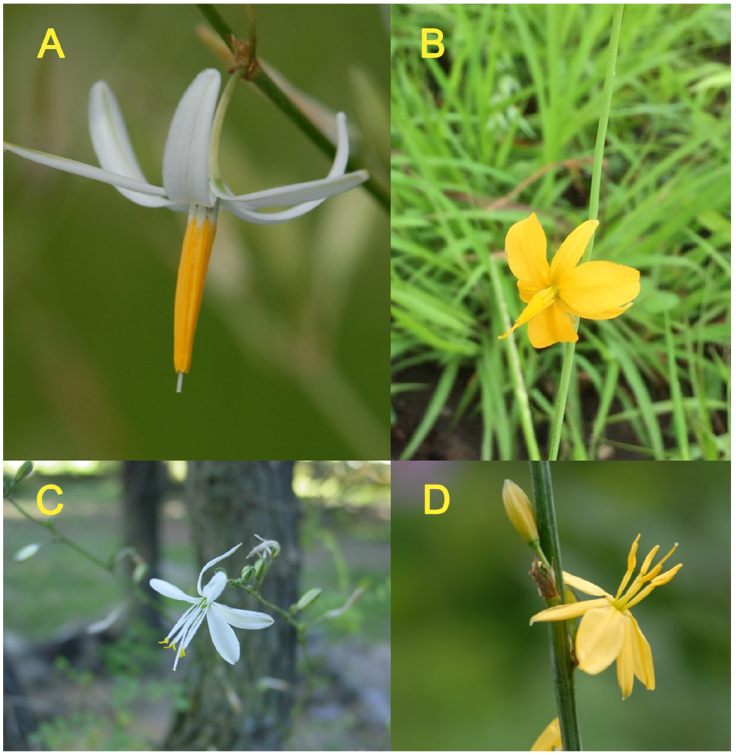

Echeandia is one of the most diverse genera in Agavoideae. It includes 85 species within the subgenera Echeandia and Mscavea Cruden (Rodríguez & Ortiz-Brunel, 2019). The former includes plants with flowers opening early in the morning, generally with elliptic white or yellow tepals, and ellipsoidal fruits. Most species grow above 1,500 m of elevation. In contrast, plants in the subgenus Mscavea have flowers which open near noon or later, most of them have narrowly elliptic white tepals and globose fruits. The plants grow below 1,500 m of elevation (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Floral variation in Echeandia. A, E. pringlei Greenm.; B, E. occidentalis Cruden; C, E. gentryi Cruden; D, E. echeandioides (Schltdl.) Cruden. Photo credits: A, C, and D by Aarón Rodríguez; B by Juan Pablo Ortiz-Brunel.

Echeandia is endemic to the American continent and Mexico is the center of diversification (Cruden, 2009; Rodríguez & Castro-Castro, 2005; Rodríguez & Ortiz-Brunel, 2019). The distribution of Echeandia extends across the Nearctic and Neotropical biogeographic regions proposed by Wallace (1876). The limits of these regions are located in the mountains of Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras (Wallace 1876). Halffter (1964) named this area as the Mexican Transition Zone (MTZ). Based on Morrone et al. (2017), the MTZ includes the Sierra Madre Occidental (SMOc), the Sierra Madre Oriental (SMOr), the Transmexican Volcanic Belt (TVB), the Sierra Madre del Sur (SMS), and the Chiapas Highlands (CH) provinces.

Centers of angiosperm species richness are located in mountainous tropical regions, such as the MTZ (Barthlott et al., 2005). In Mexico, the greatest number of angiosperm species occurs in the temperate forests in some areas of the TVB, the SMS, and the CH (Cruz-Cárdenas et al., 2013; Villaseñor & Ortiz, 2014; Rodríguez et al., 2018). Geophyte diversity is concentrated along the TVB and SMS (Cuéllar-Martínez & Sosa, 2016). Total endemism in the Mexican flora ranges from 50 to 52% (Rzedowski, 2019; Villaseñor, 2016; Villaseñor & Ortiz, 2014). Its distribution is uneven but many centers have been located along the MTZ (Alcántara & Paniagua, 2007; Salinas-Rodríguez et al., 2017; Santiago-Alvarado et al., 2016; Sosa & de Nova, 2012; Torres-Miranda et al., 2013; Villaseñor & Ortiz, 2007). Also, the MTZ has been identified as the center of diversification of some angiosperm lineages such as Bletia Ruiz & Pav. (Sosa et al., 2016), Solanum sect. Petota Dumort. (Hijmans & Spooner, 2001), Phaseolus L. (Delgado-Salinas et al., 2006), Cosmos Cav. (Vargas-Amado et al., 2013), Dioon Lindl. (Gutiérrez-Ortega et al., 2018), Quercus L. (Hipp et al., 2018), Dahlia Cav. (Carrasco-Ortiz et al., 2019; Sánchez-Chávez et al., 2019), Pinus L. (Gernandt & Pérez-de la Rosa, 2014), and the tribe Tigridieae (Munguía-Lino et al., 2015). Based on these facts, we expect that the MTZ should host the greatest species richness and endemism of Echeandia. Our aims were to analyze the spatial distribution of species richness and endemism of this genus.

Materials and methods

We compiled taxonomic, geographic, ecological, and curatorial data from different sources to generate a database. We reviewed the Mexican herbaria CICY, CIIDIR, ENCB, HGOM, IBUG, IEB, MEXU, SLPM, UAT, UAMIZ, XAL, and ZEA. Also, we searched for the available electronic records of collections in ARIZ, ASC, ASU, BRIT, COL, MO, NMC, RENO, RM, SJNM, and SNM herbaria (Thiers, 2020). We added records from Central and Southern America contained at the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF, 2018) and included all the locations cited in Cruden (1981, 1986, 1987, 1989, 1993, 1994, 1999, 2009), Cruden and McVaugh (1989), López-Ferrari and Espejo-Serna (1995), López-Ferrari et al. (2002), Rodríguez and Ortiz-Catedral (2013), and Rodríguez and Ortiz-Brunel (2019).

We corroborated all taxonomic identifications and corrected some herbarium specimens if necessary. When a record lacked geographic coordinates but had a detailed written description of the locality, we manually georeferenced it using Google Earth Pro (Google, 2018) and the Mexican localities database of INEGI (2010). In other words, we followed the Spatial Analysis Georeferencing Accuracy (SAGA) protocol (Bloom et al., 2017). It maximized the accuracy of the inferred geographic coordinates. For the same record, the elevation was obtained from a digital model of elevation, using QGIS 2.14.3 (QGIS Development Team, 2018). Duplicated and doubtful entries were deleted. The database is available upon request.

The species richness was quantified by political limits, geographical criteria, biogeographic provinces and a cell grid. For the political limits, we used the Continental level of the World Geographical Scheme for Recording Plant Distributions (Brummitt, 2001), the political divisions of the countries, and the state divisions of Mexico (INEGI, 2010). Then, we determined the species richness by latitude, longitude, and elevation. We used the biogeographic regionalization proposal of Udvardy (1975) for the USA. But for Mexico and Latin America, we combined the proposals of Morrone (2014) and Morrone et al. (2017). An adequate cell size was estimated from the total distance between extreme data points (MxD) with DIVA-GIS 4.2 program (Hijmans et al., 2004). Then, we followed the method established by Willis et al. (2003) and modified by Suárez-Mota and Villaseñor (2011) to obtain a 45 × 45 km cell size. The grid analysis was performed with DIVA-GIS 4.2 (Hijmans et al., 2004).

Endemism was estimated by political limits and biogeographic provinces using the same parameters as species richness. Centers of endemism were identified using weighted endemism (WE) and corrected weighted endemism (CWE) parameters. The level of endemism within a cell, based on the species occurring in it, was estimated by the WE (Laffan & Crisp, 2003). In contrast, CWE calculates endemism based on the proportion of endemics of the cell in relation to its species richness. Generally, cells with more species should contain more endemics (Laffan & Crisp, 2003). We used the Biodiverse program to estimate both parameters (Laffan et al., 2010). Cell size was the same for the species richness and endemism analyses.

Results

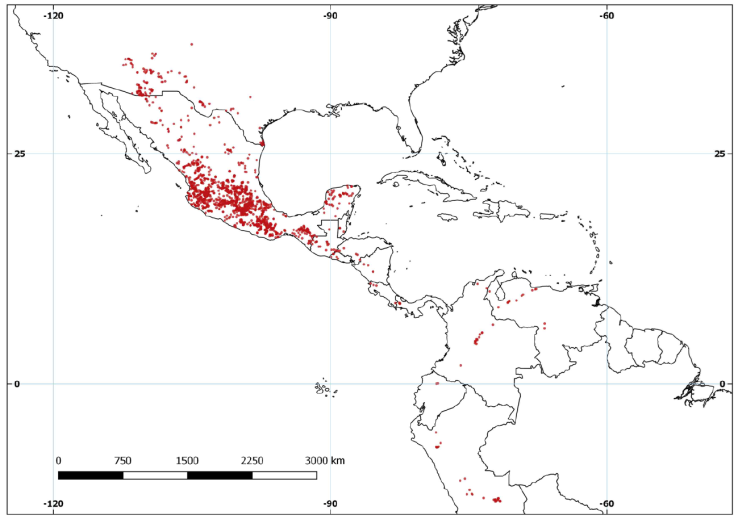

The database contained 2,078 records and 85 species of Echeandia (Table 1). There were 1,846 entries for Mexico, 125 for the USA, 60 for South America and 45 for Central America (Fig. 2). We georeferenced 46.5% of the records. The number of records per species varied from 1 in Echeandia longifolia (Weath.) Cruden, E. macrophylla Rose ex Weath., E. molinae Cruden, and E. venusta Woodson to 322 in E. flavescens (Schult. & Schult.f.) Cruden. On average, each species had 24 records.

Table 1 Spatial distribution of species richness in Echeandia. Department, Province or State abbreviations: Ags, Aguascalientes; Ahua, Ahuachapán; Ala, Alajuela; AV, Alta Verapaz; BV, Baja Verapaz; Camp, Campeche; Car, Carabobo; CDMX, Ciudad de México; Chih, Chihuahua; Chiq, Chiquimula; Chis, Chiapas; Chon, Chontales; Coah, Coahuila; Col, Colima; Dgo, Durango; Est, Estelí; FM, Francisco Morazán; Gro, Guerrero; Gto, Guanajuato; Gua, Guanacaste; Guat, Guatemala; Hgo, Hidalgo; Huan, Huancavelica; Hue, Huehuetenango; Jal, Jalisco; Jala, Jalapa; Lem, Lempira; Mag, Magdalena; Mat, Matagalpa; Mex, Estado de México; Mich, Michoacán; Mor, Morelos; Nay, Nayarit; NL, Nuevo León; Oax, Oaxaca; Oco, Ocotepeque; Por, Portuguesa; Pue, Puebla; Punt, Puntarenas; QR, Quintana Roo; Qro, Querétaro; Sin, Sinaloa; SLP, San Luis Potosí; SM, San Marcos; Son, Sonora; SS, San Salvador; Tamps, Tamaulipas; Tlax, Tlaxcala; Tot, Totonicapán; Ver, Veracruz; Yuc, Yucatán; Zac, Zacatecas. Biogeographic provinces abbreviations: BB, Balsas Basin; CH, Chiapas Highlands; CHIH, Chihuahuan Desert; PL, Pacific Lowlands; SMOc, Sierra Madre Occidental; SMOr, Sierra Madre Oriental; SMS, Sierra Madre del Sur; TAMPS, Tamaulipas; TVB, Transmexican Volcanic Belt; VER, Veracruzan; YP, Yucatán Peninsula.

| Species | Country | Department, province or state | Biogeographic province |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. E. albiflora M.Martens & Galeotti | Mexico | Pue, Ver | TVB, VER |

| 2. E. altipratensis Cruden | Guatemala | Hue, SM, Tot | CH |

| Mexico | Chis | ||

| 3. E. atoyacana Cruden | Mexico | Gro, Mex | BB, PL |

| 4. E. attenuata Cruden | Mexico | Dgo, Sin | PL, SMOc |

| 5. E. bolivarensis Cruden | Venezuela | Bolívar | Pantepui |

| 6. E. breedlovei Cruden | Mexico | Chis, Oax | PL, VER |

| 7. E. campechiana Cruden | Mexico | Camp, Yuc | YP |

| 8. E. chandleri (Greenm. & C.H.Thomps.) Cruden | Mexico, USA | Coah, NL, Tamps, Texas | CHIH, Grasslands, SMOr |

| 9. E. chiapensis Cruden | Mexico | Chis, Oax | AC, PL, VER |

| 10. E. ciliata (Kunth) Cruden | Peru | Cajamarca | Cauca, Puna, Yungas |

| 11. E. coalcomanensis Cruden | Mexico | Jal, Mich, Nay | SMS, TVB |

| 12. E. confertiflora Cruden | Mexico | Oax | BB |

| 13. E. conzattii Cruden | Mexico | Gro, Oax | BB, SMS, TVB |

| 14. E. crudeniana Aarón Rodr. | Mexico | Nay | PL |

| 15. E. denticulata Cruden | Colombia, Venezuela | Boyacá, Cundinamarca Mérida | Guajira, Magdalena, Paramo |

| 16. E. drepanoides (Greenm.) Cruden | Mexico | Oax | BB, SMS |

| 17. E. durangensis (Greenm.) Cruden | Mexico | Ags, CDMX, Chih, Dgo, Gto, Hgo, Jal, Mex, Mich, Mor, NL, Qro, SLP, Ver, Zac | CHIH, PL, SMOc, SMOr, TVB |

| 18. E. echeandioides (Schltdl.) Cruden | Mexico | CDMX, Gro, Mex, Mich, Mor, Oax, Pue | BB, SMS, TVB |

| 19. E. elegans Cruden | Mexico | Gro, Mor | BB, SMS |

| 20. E. falcata Cruden | Mexico | Gto, Mich, Qro | CHIH, SMOr |

| 21. E. flavescens (Schult. & Schult.f.) Cruden | Mexico | Ags, CDMX, Chih, Coah, Dgo, Gto, Hgo, Jal, Mex, Mich, NL, Oax, Pue, Qro, SLP, Son, Tlax, Ver, Zac | BB, CHIH, Chihuahuan, Grasslands, Madrean Cordillera, PL, Rocky Mountains, SMOc, SMOr, |

| USA | Arizona, New Mexico, Texas | SMS, Sonoran, TAMPS, TVB | |

| 22. E. flexuosa Greenm. | Mexico | Jal, Gto, Mich, Nay, Qro, Zac | CHIH, PL, SMOc, TVB |

| 23. E. formosa (Weath.) Cruden | Honduras | FM | CH, SMS |

| Mexico | Chis, Oax | ||

| 24. E. gentryi Cruden | Mexico | Dgo, Jal, Nay, Sin, Zac | PL, SMOc, TVB |

| 25. E. gracilis Cruden | Mexico | CDMX, Hgo, Mex, Mor, Pue | SMOr, TVB |

| 26. E. graminea M.Martens & Galeotti | Mexico | Oax, Pue, Ver | BB, PL, SMS, TVB |

| 27. E. grandiflora Cruden | Mexico | Oax | PL, SMS |

| 28. E. hallbergii Cruden | Mexico | Oax | SMS |

| 29. E. herrerae (Killip) Cruden | Peru | Apurimac, Cuzco, Huan, Junín | Rondônia, Ucayali, Yungas |

| 30. E. hintonii Cruden | Mexico | Gro | BB, SMS |

| 31. E. hirticaulis Cruden | Mexico | Gro, Mex, Mich, Oax | BB, SMS, TVB |

| 32. E. imbricata Cruden | Mexico | Gro, Jal, Mich, Mor | BB, PL, SMS, TVB |

| 33. E. jaliscensis Aarón Rodr. & Brunel | Mexico | Jal | TVB |

| 34. E. lehmannii (Baker) Marais & Reilly | Ecuador | Pichincha | Cauca |

| 35. E. leucantha Klotzsch | Colombia | Mag | CH, Guajira, Guatuso-Talamanca, PL, Puntarenas-Chiriquí, Savanna, Venezuelan |

| Costa Rica | Ala, Gua, Punt | ||

| Honduras | FM | ||

| Nicaragua | Chon, Est, Mat | ||

| Venezuela | Car, Por, Tovar, Zulia | ||

| 36. E. llanicola Cruden | Mexico | Oax | SMS |

| 37. E. longifolia (Weath.) Cruden | Mexico | Oax | SMS |

| 38. E. longipedicellata Cruden | Guatemala | Hue | CH, SMOc, SMS, TVB |

| Mexico | Chis, Dgo, Gro, Jal, Mex, Mich, Mor, Oax, Pue, Tlax, Ver | ||

| 39. E. luteola Cruden | Belize | Cayo | VER, YP |

| Mexico | Camp, QR, Yuc | ||

| 40. E. macrophylla Rose ex Weath. | Mexico | SLP | SMOr |

| 41. E. magnifica López-Ferr., Espejo & Ceja | Mexico | Gro | BB, SMS |

| 42. E. matudae Cruden | El Salvador | Santa Ana, SS | CH, PL, SMS, VER |

| Guatemala | AV, Hue, Jala | ||

| Mexico | Chis, Oax | ||

| 43. E. mcvaughii Cruden | Mexico | Jal, Nay | CHIH, PL, SMS, TVB |

| 44. E. mexiae Cruden | Mexico | Gro, Oax | BB, SMS, TVB |

| 45. E. mexicana Cruden | Mexico | CDMX, Gto, Hgo, Jal, Mex, Mich, Mor, Nay, Oax, Pue, Qro, SLP, Ver | BB, CHIH, PL, SMOc, SMOr, TVB |

| 46. E. michoacensis (Poelln.) Cruden | Mexico | Col, Gto, Mich | PL, SMOr, SMS, TVB |

| 47. E. mirandae Cruden | Mexico | Oax, Pue | BB, SMS |

| 48. E. molinae Cruden | Guatemala | BV | CH |

| 49. E. montealbanensis Cruden | Mexico | Oax | BB, PL, SMS |

| 50. E. nana (Baker) Cruden | Mexico | CDMX, Gto, Hgo, Jal, Mex, Mich, Mor, Pue, Qro, SLP, Tlax, Ver | CHIH, SMOr, TVB |

| 51. E. nayaritensis Cruden | Mexico | Nay, Sin | PL |

| 52. E. novogaliciana Aarón Rodr. & Ortiz-Cat. | Mexico | Dgo, Nay, Zac | CHIH, SMOc |

| 53. E. oaxacana Cruden | Mexico | Oax | BB, PL, SMS |

| 54. E. occidentalis Cruden | Mexico | Jal, Mich, Nay, Sin, Zac | BB, CHIH, PL, SMOc, TVB |

| 55. E. palmeri Cruden | Mexico | Chih, Dgo, Son, Zac | CHIH, SMOc |

| 56. E. paniculata Rose | Mexico | CDMX, Gro, Gto, Hgo, Jal, Mex, Mich, Mor, Oax, Pue, Qro, SLP, Ver, Zac | BB, CHIH, PL, SMOc, SMOr, TVB |

| 57. E. parva Cruden | Mexico | Mor, Oax, Pue | BB |

| 58. E. parvicapsulata Cruden | Mexico | Col, Jal, Nay, Sin | PL, SMS |

| 59. E. parviflora Baker | Guatemala | Chiq | BB, CH, CHIH, SMS, TVB, VER |

| Mexico | Chis, Col, Gro, Jal, Mex, Mor, Oax, Pue, Ver | ||

| 60. E. petenensis Cruden | Belize | Cayo, Toledo | VER, YP |

| Guatemala | Petén | ||

| Mexico | Camp | ||

| 61. E. pihuamensis Cruden | Mexico | Col, Jal | PL |

| 62. E. pittieri Cruden | Colombia | Mag, Valle del Cauca | Guajira, Magdalena, Puntarenas-Chiriquí |

| Panama | Chiriquí | ||

| 63. E. platyphylla (Greenm.) Cruden | Mexico | Pue | BB |

| 64. E. pringlei Greenm. | Mexico | Jal, Nay | TVB |

| 65. E. pseudopetiolata Cruden | Mexico | Gro | SMS |

| 66. E. pseudoreflexa Cruden | Mexico | Chis | CH, VER |

| 67. E. ramosissima (C.Presl) Cruden | Mexico | Chih, Col, Dgo, Gro, Jal, Mex, Mich, Mor Nay, Sin, Son | BB, CHIH, PL, SMOc, TVB |

| 68. E. reflexa (Cav.) Rose | Mexico | Ags, CDMX, Chis, Gto, Hgo, Jal, Mich, NL., Oax, Pue, Qro, SLP, Tamps, Ver | BB, CH, CHIH, PL, SMOc, SMOr, TVB, VER |

| 69. E. robusta Cruden | Mexico | Jal | PL, SMS, TVB |

| 70. E. sanmiguelensis Cruden | Mexico | Gto | CHIH |

| 71. E. scabrella (Benth.) Cruden | Mexico | Ags, Coah, Chih, Dgo, Gto, Jal, Mich, Nay, Zac | CHIH, PL, SMOc, TVB |

| 72. E. sinaloensis Cruden | Mexico | Jal, Nay, Sin | PL, TVB |

| 73. E. skinneri (Baker) Cruden | El Salvador | La Libertad, Santa Ana | CH, PL, VER |

| Guatemala | AV | ||

| Honduras | Chol | ||

| Mexico | Chis | ||

| 74. E. smithii Cruden | Mexico | Oax | SMS |

| 75. E. tamaulipensis Cruden | Mexico | Tamps | TAMPS, VER |

| 76. E. taxacana Cruden | Mexico | Gro, Mex, Mor, Oax | BB, SMS, TVB |

| 77. E. tenuifolia Cruden | Mexico | Oax | BB, SMS |

| 78. E. tenuis (Weath.) Cruden | Mexico | Gro, Mor, Oax | BB, SMS, TVB |

| 79. E. texensis Cruden | USA | Texas | Grasslands |

| 80. E. udipratensis Cruden | Mexico | Jal | TVB |

| 81. E. vaginata Cruden | Mexico | Oax | BB, SMS |

| 82. E. venusta Woodson | Panama | Chiriquí | Puntarenas-Chiriquí |

| 83. E. vestita (Baker) Cruden | Guatemala | Quiché | BB, CH, CHIH, SMS, |

| Mexico | Chis, Jal, Mich, Oax, Pue, Tlax, Ver | TVB | |

| 84. E. weberbaueri (Poelln.) Cruden | Peru | Huan | Rondônia, Yungas |

| 85. E. williamsii Cruden | El Salvador | Ahua | CH, PL, VER |

| Guatemala | AV, BV, Chiq, Guat, Hue, Jala | ||

| Honduras | Lem, Oco | ||

| Mexico | Chis |

With 74 species, Mexico had the highest species richness of Echeandia followed by Guatemala with 9, and then Honduras with 4. The USA, El Salvador, Venezuela, Colombia, and Peru had 3 species each. Two species were registered for both Belize and Panama while Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Ecuador, each had 1 (Table 1). Within Mexico, the states of Oaxaca (31), Jalisco (24), and Guerrero (16) had the greatest number of species.

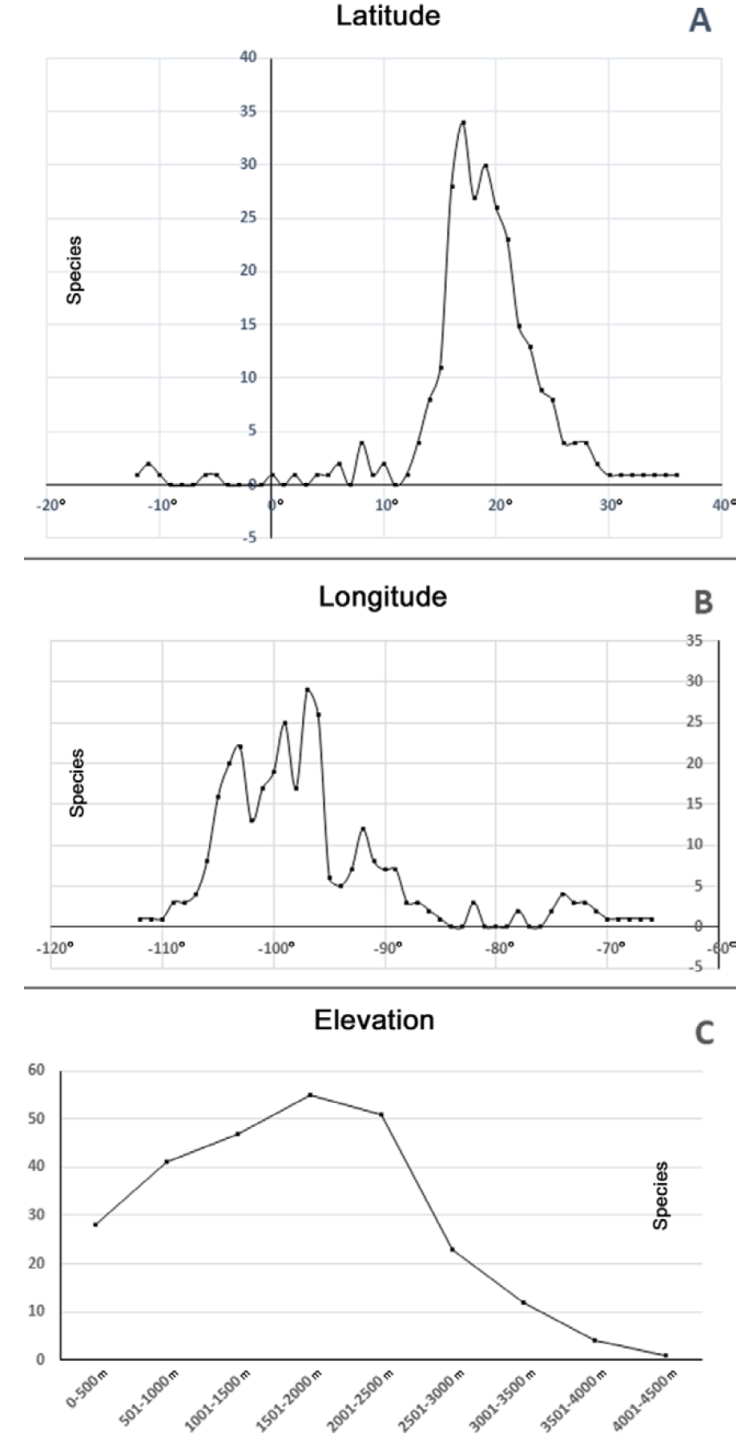

Latitudinally, Echeandia presented its greatest diversity between 17° and 21° N (Fig. 3A). The genus was markedly diverse at 97°, 99°, and 103° W (Fig. 3B). At one extreme, Echeandia campechiana Cruden, E. crudeniana Aarón Rodr., E. luteola Cruden, and E. texensis Cruden grew at sea level in Mexico and the USA. In contrast, E. herrerae (Killip) Cruden inhabited the highest elevational limit of the genus at 4,121 m, in Peru. In Central America, E. altipratensis Cruden reached 3,550 m, in Guatemala. Meanwhile, in Mexico E. durangensis (Greenm.) Cruden and E. longipedicellata Cruden were found at 3,300 m. However, most species were collected between 1,500 and 2,500 m of elevation (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3 Echeandia species richness by geographical criteria. A, Latitude; B, longitude; C, elevation.

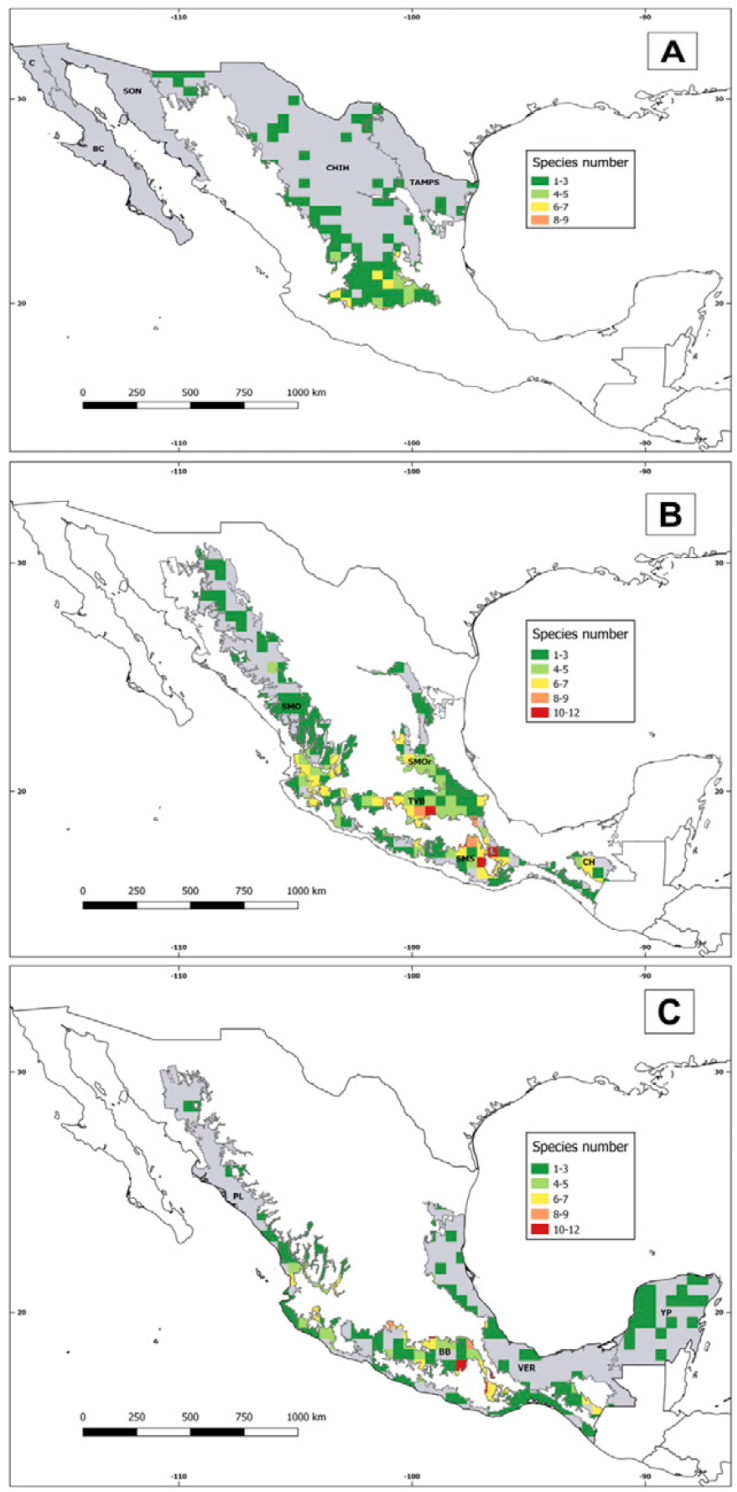

Echeandia was documented in 29 of the 70 biogeographic provinces of Latin America and in 5 out of 16 in the USA (Table 1). The spatial distribution was heterogeneous but concentrated in Mexico. The SMS had 39 species. The Pacific Lowlands (PL) and the TVB had 32, each. The Balsas Basin (BB), the Chihuahuan Desert (CHIH), and the SMOc, had 29, 18, and 15, respectively. Then, the CH and Veracruzan provinces had 12, each. Lastly, the SMOr recorded 11 species. Adding numbers up, the MTZ contained 61 species whereas the Neotropic and the Nearctic had 63 and 19 species, individually.

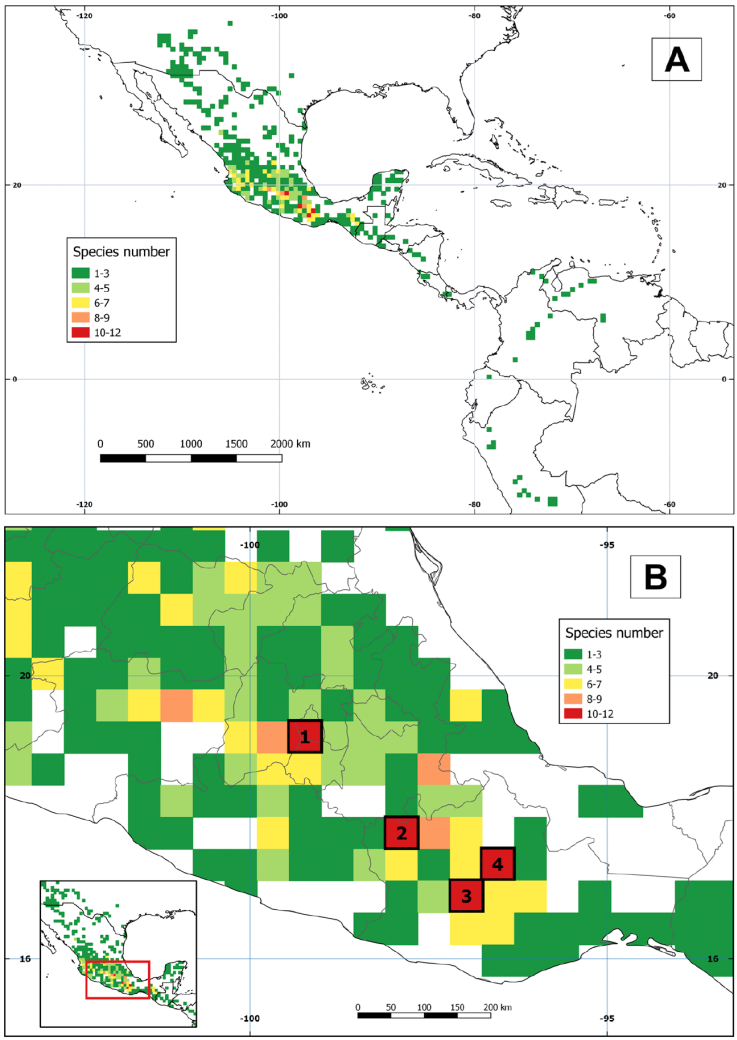

The grid analysis revealed 4 cells with high species richness (Fig. 4A). Cell 1 had 12 species and was located in the limits among Ciudad de México, Estado de México, and the state of Morelos. Cells 2, 3, and 4 contained 11 species each. Cell 2 occurred in the Oaxaca-Puebla state border, while cells 3 and 4 were situated in the confluence of the Central Valleys with the southern and northern mountains in Oaxaca (Fig. 4B). All cells with more than 3 species were in Mexico. In Central America, one cell in Guatemala had 3 species. El Salvador, Honduras, and Panama had cells with 2 species, while the rest of Central and all South America presented only 1 species per cell (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4 Species richness of Echeandia by a cell of 45 × 45 km. A, General analysis; B, close-up of central Mexico.

Among countries, the number of endemic species was contrasting (Table 1). For Mexico, 63 were reported followed by Peru with 3. Ecuador, the USA, Guatemala, Panama, and Venezuela, each had 1. In Mexico, Oaxaca was the state with the highest number of endemic species, including Echeandia confertiflora Cruden, E. drepanoides (Greenm.) Cruden, E. grandiflora Cruden, E. hallbergii Cruden, E. llanicola Cruden, E. longifolia, E. montealbanensis Cruden, E. oaxacana Cruden, E. smithii Cruden, E. tenuifolia Cruden, and E. vaginata Cruden. Echeandia hintonii Cruden, E. magnifica López-Ferr., Espejo & Ceja, and E. pseudopetiolata Cruden grew only in Guerrero while E. jaliscensis Aarón Rodr. & Brunel, E. robusta Cruden, and E. udipratensis Cruden were found only in Jalisco (Table 1).

Based on biogeographic provinces, Echeandia hallbergii, E. llanicola, E. longifolia, E. pseudopetiolata, and E. smithii determined the SMS to be the province with the highest number of endemic species. Meanwhile, E. confertiflora, E. parva Cruden, and E. platyphylla (Greenm.) Cruden were endemic to the BB, while E. crudeniana, E. nayaritensis Cruden, and E. pihuamensis Cruden were exclusive to the PL. The TVB and the CH had 2 endemics each. Provinces with 1 endemic species included Grasslands, CHIH, SMOr, Yucatán Peninsula (YP), Puntarenas-Chiriquí, Pantepui, and Cauca (Table 1).

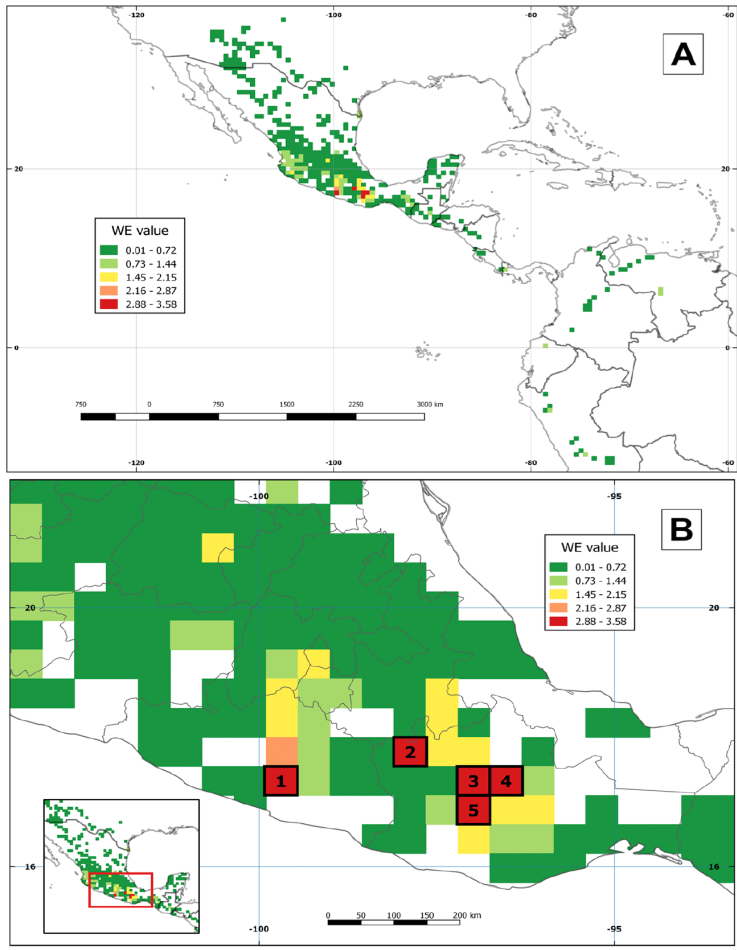

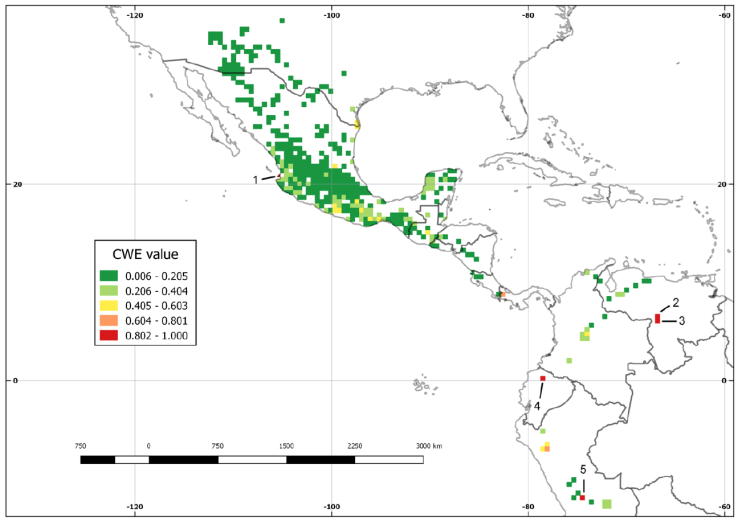

The WE analysis revealed 5 cells with the highest values (2.88 to 3.58), all located in Mexico. Cell 1 fell in Guerrero but cells 2, 3, 4, and 5 situated in Oaxaca. In Central and South America, the cell values varied from 0.01 to 1.44 (Fig. 5A). Cells with 1.45 to 2.15 values were identified in Ciudad de México, Jalisco, Estado de México, Morelos, Puebla, and Querétaro (Fig. 5B). Even though the CWE analysis revealed 5 cells with a value of 1, these had different distribution (Fig. 6). Cell 1 located in Mexico, cells 2 and 3 in Venezuela, cell 4 in Ecuador, and cell 5 in Peru. Cells with values between 0.6 and 0.8 were observed in Panama and Peru. Finally, Mexico, the USA, Guatemala, Colombia, and Peru hosted cells with 0.4 to 0.6 values.

Discussion

The database contained 2,078 records and out of these, we georeferenced 966 of them (46.5%). Even though several publications failed to state how or if the data were georeferenced, this proportion compares with similar analyses. For instance, Munguía-Lino et al. (2015) georeferenced 47% of the occurrence points in the tribe Tigridieae (Iridaceae) of North America and Carrasco-Ortiz et al. (2019) did the same for 61% of the records in Dahlia (Asteraceae). In Sedum (Crassulaceae) from the Sierra Madre del Sur (Mexico), Aragón-Parada et al. (2019) georeferenced 91% of the geographical data. The confidence of our results depended on the taxonomic identification and the quality of geographic coordinates included the estimated ones. We followed the SAGA protocol and according with Bloom et al. (2017), this method outpaced any other georeferencing scheme.

In biogeography, the uneven distribution of species richness makes a striking pattern. Even though political divisions do not have a biological significance, they are important for conservation decisions (Whittaker et al., 2005). Mexico is the center of diversification of many lineages of Agavoideae such as Agave L. sensu stricto, Manfreda Salisb., Polianthes L., and Yucca L. (Castro-Castro et al., 2016; Castro-Castro et al., 2018; García-Mendoza, 2002; García-Mendoza, 2011; Good-Avila et al., 2006; Jiménez-Barron et al., 2020). The highest species richness of Agavoideae is concentrated in Jalisco and Oaxaca (Castro-Castro, 2017; García-Mendoza, 2004). Echeandia followed a similar pattern.

As botanical exploration continues in Mexico, the number of species increases, including those in Echeandia. Espejo-Serna and López-Ferrari (1993) report 51 species and Cruden (2009) lists 59. Rodríguez and Ortiz-Catedral (2013) mention 69, while Villaseñor (2016) indicates the presence of 68 species. We have documented 74 species, adding the presence of E. altipratensis, E. petenensis Cruden, and E. williamsii Cruden within the Mexican territory. Also, we have included the recently described E. jaliscensis (Rodríguez & Ortiz-Brunel, 2019). Most likely, future botanical exploration will lead into the discovery of new species for the genus.

Plant species richness increases towards the equator. However, within the tropics, mountainous zones show the highest values (Barthlott et al., 2005; Ulloa-Ulloa et al., 2017). The spatial distribution of Echeandia coincided with these patterns. Echeandia species richness concentrated between 17° and 21° N and from 1,500 to 2,500 m of elevation. These ranges corresponded to the highlands of Oaxaca, Estado de México, and Morelos. The latitudinal and elevational patterns of Echeandia were similar to those of tribe Tigridieae (Iridaceae) (Munguía-Lino et al., 2015) and Solanum section Petota (Solanaceae) (Hijmans & Spooner, 2001). Also, Echeandia was markedly diverse at 97°, 99°, and 103° W, which corresponded to some areas of the SMS and the TVB. Latitudinal and elevational ranges with more species of Echeandia corresponded to the range of the pine-oak forest. Villaseñor and Ortiz (2014) identify this vegetation type as home of the largest angiosperm diversity in Mexico.

The highest diversity of Echeandia was concentrated along the MTZ, particularly in the SMS and TVB. Conversely, geophyte monocotyledons have their highest diversity along the TVB and the SMS (Cuéllar-Martínez & Sosa, 2016). Dahlia (Carrasco-Ortiz et al., 2019) and Echeandia shared the same area of species richness in the SMS. Additionally, we identified another pattern of Echeandia species richness.

Several species of Echeandia were located at the limits of the MTZ and the Neotropical region. These areas located between the pine-oak forest and the tropical deciduous forest. For example, E. conzattii Cruden, E. echeandioides (Schltdl.) Cruden, E. elegans Cruden, E. hintonii, E. hirticaulis Cruden, E. magnifica, E. mexiae Cruden, E. mirandae Cruden, E. taxacana Cruden, E. tenuifolia, E. tenuis (Weath.) Cruden, and E. vaginata occurred in the boundaries between the TVB or the SMS and the BB. The other case was observed along the PL. This province extends from southern Sonora to Nicaragua and has the widest latitudinal range (Morrone, 2014). At some points, it converges with the SMOc, the TVB, the SMS, and the CH. The distribution of E. attenuata Cruden, E. gentryi Cruden, E. grandiflora, E. mcvaughii Cruden, E. parvicapsulata Cruden, E. robusta, and E. sinaloensis Cruden included the PL and the MTZ. This evidence explains the high number of species observed in the PL and the BB.

A similar pattern was identified along the boundaries between the MTZ and the Nearctic region. The CHIH registered 18 species (Table 1). The distribution of some species of the SMOc, the SMOr, and the TVB extended to the vicinity of the CHIH. In other words, species of the temperate forest in the MTZ stretched their distribution to the mountains with dry conditions of the CHIH. This pattern was not observed with other provinces of the Nearctic. The Tamaulipas and the Sonoran Desert provinces have contact with the SMOr and the SMOc, respectively. However, only 4 and 1 species were registered for each province. Plains and low sierras with mesquite-grassland and desert cover both provinces (Ferrusquía-Villafranca, 1993; Leopold, 1950; Phillips & Wentworth, 2000; Rzedowski, 1986). It has been observed that topographic complex areas show a higher biodiversity in comparison with adjacent lowlands (Badgley et al., 2017). Echeandia had low species richness in provinces with lowlands covered by mesquite-grassland and desert.

The geographical distribution of Echeandia included the MTZ, the South American Transition Zone (STZ), the Neotropic, and the Nearctic. With 63 species, the Neotropic had the highest number of species but its territorial extension is also several times larger than the MTZ. Furthermore, most species registered in the Neotropic were recorded in the provinces situated next to the MTZ in Mexico. With some exceptions, Darlington (1957) says that transition zones have poor biodiversity. At the STZ and with 2 species recorded, Echeandia supports his observation, but the MTZ represents the contrary. Good-Avila et al. (2006) show evidence for a sister group relationship between the Anthericeae and Agavaceae clades. They separated from each other about 30 to 35 Mya. Further, Agave sensu lato originated 8-10 Mya. Within Agave sensu lato, Jiménez-Barron et al. (2020) show data supporting 2 recent diversification events at 2.68 and 6.18 Mya. Both Agave s.l. and Echeandia have a similar pattern of species richness distribution. It follows that Mexico represents the center of origin and diversification of Echeandia with a subsequent dispersal to the south. This observations could explain the low species richness in Central and South America but needs further evaluation based on a robust phylogenetic hypothesis.

With 12 species, the richest cell was located at the point where the state borders of Morelos, Estado de México, and Ciudad de México coincide. This pattern was very similar to those of the Mexican geophytes (Sosa & Loera, 2017) and the tribe Tigridieae (Munguía-Lino et al., 2015). Two cells, with 11 species each, were situated in Oaxaca at the limits between the SMS and the BB, similar to the case of Dahlia (Carrasco-Ortiz et al., 2019). Three out of 4 cells with the highest species richness were located in the MTZ but included portions of the BB. The remaining cell fell mostly in the BB but overlapped a little with the SMS (Fig. 7). This implies the presence of the tropical deciduous forest and the pine-oak forest in the 4 cells. The convergence of 2 biogeographic provinces and therefore, of 2 vegetation types, could explain the high number of species in these cells.

Figure 7 Comparison of the species richness by biogeographical regions. A, Nearctic; B, Mexican Transition Zone; C, Neotropical. Abbreviations: BB, Balsas Basin; BC, Baja Californian; C, Californian; CH, Chiapas Highlands; CHIH, Chihuahuan Desert; PL, Pacific Lowlands; SMOc, Sierra Madre Occidental; SMOr, Sierra Madre Oriental; SMS, Sierra Madre del Sur; SON, Sonoran; TAMPS, Tamaulipas; TVB, Transmexican Volcanic Belt; VER, Veracruzan; YP, Yucatán Peninsula.

The endemic vascular flora of Mexico varies from 49.8% (Villaseñor, 2016) to 52.5% (Ulloa-Ulloa et al., 2017). Espejo-Serna (2012) estimates that 84.6% of the species of Echeandia are endemic to the country, which coincides with the 85.1% obtained in this work. Both estimates are greater than the global Mexican values. Therefore, Echeandia is a good surrogate of the endemic flora of Mexico.

The highest species richness and endemism of Echeandia were concentrated in the SMS. It had 39 species and 5 of them were endemic to the province. It also held the 5 cells with the highest values recovered by the WE analysis (Fig. 5, Table 2). However, endemism in the SMS was unevenly distributed. Based on endemism patterns, the SMS is divided in 3 subprovinces and 5 districts (Santiago-Alvarado et al., 2016; Morrone, 2017). The endemism of Echeandia was greater in the Eastern Sierra Madre del Sur subprovince. Cell 1 located in Guerrero and E. pseudopetiolata defined it. This zone was previously identified as the Sierra Madre del Sur Guerrerense district (Santiago-Alvarado et al., 2016). The 4 remaining cells occurred in Oaxaca, all of them in the Sierra Madre del Sur Oaxaqueña district (Santiago-Alvarado et al., 2016). Echeandia confertiflora defined cell 2 while E. llanicola was restricted to the cell 4. Cells 3 and 5 had no strict endemics but the species contributing to their values are listed in Table 2. These cells of Oaxaca were identified as endemism areas by Rodríguez et al. (2018) and Aragón-Parada et al. (2019).

Table 2 Species in the highest valued cells of the weighted endemism analysis.

| Cell | Present | Endemic |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Echeandia hintonii, E. magnifica, E. parviflora, E. pseudopetiolata, E. taxacana | E. pseudopetiolata |

| 2 | Echeandia confertiflora, E. echeandioides, E. mexiae, E. mexicana, E. montealbanensis, E. parva, E. parviflora, E. reflexa, E. taxacana, E. tenuifolia, E. vestita | E. confertiflora |

| 3 | Echeandia conzatti, E. echeandioides, E. hallbergii, E. mexicana, E. smithii, E. vaginata, E. vestita | |

| 4 | Echeandia drepanoides, E. echeandioides, E. formosa, E. hallbergii, E. llanicola, E. longipedicellata, E. matudae, E. mexicana, E. montealbanensis, E. smithii, E. vestita | E. llanicola |

| 5 | Echeandia drepanoides, E. echeandioides, E. flavescens, E. hallbergii, E. matudae, E. montealbanensis, E. parviflora, E. reflexa, E. smithii, E. vaginata, E. vestita |

Correspondingly, the CWE recovered 5 cells with a value of 1 and a single strict endemic (Fig. 6). Cell 1 placed in Mexico and was defined by the presence of Echeandia crudeniana, known only from the type locality in Punta Mita Peninsula, Bahía de Banderas, Nayarit (Rodríguez & Ortiz-Catedral, 2013). The other 4 cells pertained to South America. Cells 2 and 3 situated in Venezuela and E. bolivarensis Cruden supported them. Ecuador housed cell 4 with E. lehmannii (Baker) Marais & Reilly. Last of all, Peru had cell 5 and E. weberbaueri (Poelln.) Cruden defined it. Micro-endemic species are common in Echeandia (Cruden, 2009) and our results confirmed this observation. Since, in South America they were geographically isolated from other species.

Monocot geophyte diversification and distribution are correlated with wide temperature ranges and precipitation seasonality (Cuéllar-Martínez & Sosa, 2016; Sosa & Loera, 2017; Howard et al., 2019). The MTZ includes the major mountain chains in Mexico and has a complex tectonic and volcanic history (Mastretta-Yanes et al., 2015). It also shows temperature gradients and rain seasonality. Such topographic and climatic diversity promotes speciation, accumulation of species via dispersal, persistence and endemism. Overall, angiosperm spatial richness distribution and endemism patterns fall along the MTZ (Cruz-Cárdenas et al., 2013; Rodríguez et al., 2018; Sosa & De-Nova, 2012). And particularly, Echeandia fits perfectly in this scenario. We hope this species rich genus will promote botanical exploration leading to the discovery of novelties and contributes to build up a strategy for the species conservation of the genus in situ and ex situ.

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)