Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Mexican law review

versión On-line ISSN 2448-5306versión impresa ISSN 1870-0578

Mex. law rev vol.4 no.2 Ciudad de México ene./jun. 2012

Articles

Institutional Changes in the Public Prosecutor's Office: The Cases of Mexico, Chile and Brazil

Azul América Aguilar Aguilar*

Recibido: 7 de abril de 2011;

Aceptado para su publicación: 26 de junio de 2011.

Abstract

Given the critical role played by the Public Prosecutor's Office in the criminal justice system, the reform of its powers and underlying framework is fundamental in enhancing the rule of law and democracy. This paper analyses two important aspects of reforms introduced in Brazil, Chile and Mexico that affect the way in which the Public Prosecutor's Office (the "PPO") performs its daily duties: 1) criminal procedure; and 2) institutional location. This paper takes a comparative approach to evaluate efforts carried out by politicians to modify key aspects of the criminal justice system, as well as overcome key challenges. Emphasis is placed on recently enacted changes to the Constitution, organic laws, criminal codes and criminal procedures.

Key Words: Judicial System Reform, Public Prosecutor, Institutional Framework, Criminal Procedure, Political Autonomy, Rule of Law, Democracy.

Resumen

La reforma al Ministerio Público (MP) es considerada un paso fundamental para fortalecer el Estado de derecho y el régimen democrático, dado que la institución es un jugador clave en el sistema de justicia penal. Este documento analiza las reformas introducidas en Brasil, Chile y México a dos dimensiones que afectan la manera en que el MP realiza sus actividades diarias: 1) el procedimiento penal, y 2) su ubicación institucional. Desde una perspectiva comparada este trabajo señala cuáles son los principales esfuerzos llevados a cabo por los representantes para cambiar el entramado institucional de la procuración de justicia y cuáles son los principales retos a superar. Este documento se concentra en el análisis de diversos textos legales como Constituciones, leyes orgánicas, códigos penales y códigos de procedimientos penales con el objetivo de observar hasta qué punto ha sido reformada cada una de las dimensiones aquí estudiadas.

Palabras clave: Reforma al sistema de justicia, configuración institucional del Ministerio Público, procedimiento penal, autonomía política, Estado de derecho, democracia.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. Introduction

II. A Brief History of the PPO's Institutional Structure

III. Analysis of Reforms to Criminal Procedure

1. Brazil

2. Chile

3. Mexico

4. Comparative Overview

IV. Changes to the PPO's Institutional Framework. Consequences for its Autonomy

1. Brazil

2. Chile

3. Mexico

4. Comparative Overview

V. Concluding Remarks: Comparison of Reforms to the PPO in Brazil, Chile and Mexico

I. Introduction

Since democratic politics are fundamentally incompatible with the previous authoritarian system, elected officials normally change many institutional features —including electoral rules, system of government (i.e. parliamentarian or presidential) etc.— in the years immediately following democratic reform. Following these changes, further reforms are also often considered necessary, including major changes to the criminal justice system. In newly-formed democracies such as Brazil, Chile and Mexico, systematic reform of the Public Prosecutor's Office (PPO) has been critical in advancing the rule of law, implementing democratic processes and codifying international human rights provisions in domestic law. Under authoritarian rule, PPOs were often used by the executive branch to punish political enemies; and due process was often granted as a privilege to the regime's supporters.

Chile serves as a notable example. There the entire legal system was subservient to Augusto Pinochet's military junta, which exploited it to punish enemies of the State. During the investigative stage, torture and preventive imprisonment were widely used to extract information and repress political dissents.1 In Mexico and Brazil, access to justice was (and often still is) a privilege reserved only for those with economic means (Mexico)2 or social standing (Brazil).3 It is clear, however, that a criminal justice system that fails to facilitate equal access and due process for its citizens shall always be subject to undue influence and, as a result, violate basic democratic principles.

In this article, I describe changes to the PPO realized at a national level during the recent democratic transition periods in Brazil, Chile and Mexico,4 and analyse what these countries did to modify this institution's rules and procedures. Below, I describe how the PPO was restructured in two major areas after legislative reforms were approved: 1) criminal procedure; and 2) the PPO's institutional framework.

With respect to the first area, it should be noted that the criminal justice system implemented by Spain and Portugal in Latin America during the colonial era was by nature inquisitorial. In this system, the judge's role is predominant whereas the participation of defendants is limited. Indeed, "the accused is conceived as an object of the (criminal) process more than a subject with rights."5 When Brazil, Chile and Mexico transitioned to democracy, major efforts were made to modify the rules of criminal procedure through the adoption, either whole or in part, of the accusatory model. According to many scholars and activists, the inquisitorial model lacked transparency and reliability since it represented "an authoritarian organizational culture."6 In effect, the accusatory model not only enhances the protection of victims' and defendants' rights but also helps curb human rights abuse in general.

The second area refers to organic structure; in particular, the institutional location of the PPO and thus the autonomy of the public prosecutor. Historically, most Latin American countries placed the PPO within the framework of the Executive branch, meaning that the public prosecutor was considered part of the presidential cabinet and, as such, subject to dismissal at the President's sole discretion. When democracy expanded in the region, many proposals were discussed to promote higher levels of autonomy for the public prosecutor and modify his or her appointment, promotion and dismissal.

This article analyses several recently enacted laws and regulations including constitutional reforms, organic laws, criminal codes and criminal procedures for the purpose of evaluating the extent of institutional change as well as specific areas which require further reform. It is worth noting that any evaluation of changes made to the PPO's rules and procedures is strongly linked to the general implementation of the rule of law; not necessarily how these new rules have been implemented in practice. "Constitutional engineering" or de jure legal reform is an important and necessary (but clearly insufficient) step for newly-formed democracies that aspire to cast off authoritarian practices.

This article is organized as follows: Part II presents a synopsis of the PPO's institutional structure before reforms were implemented. Part III discusses changes made to criminal procedures and the PPO's institutional location in all three countries. Part IV offers a comparative analysis of the reforms; pointing out some notable differences between the three nations, and the main challenges ahead to implement these rules and help achieve modernization.

II. A Brief History of the PPO's Institutional Structure

A quick overview of the history of the Public Prosecutor's Office in both Chile and Mexico shows that it was originally established by the Spanish PPO to help prosecute and adjudicate crimes and heresy.7 In Brazil, the PPO was based on Portugal's Ministério Público which featured a Promotor Público who represented the interests of the Emperor.8 For several decades after independence, it was not considered necessary to establish an institution similar to the current PPO.9 In fact, a Code of Criminal Procedure (CCP) was never enacted; criminal matters were regulated pursuant to laws dating back to colonial times. When the first criminal codes were introduced, their development followed the inquisitorial tradition.10 The Codes of Criminal Procedures enacted by Brazil (1832), Chile (1906) and Mexico (1880) were inspired by the legal framework governing medieval Europe, a considerable time before Napoleon's Code d'Instruction Criminelle; in other words, before the consolidation of what eventually became a "mixed" criminal procedure system. In all three countries, no change occurred until the late 20th century.

In the long constitutional history of Brazil, the PPO was mentioned at times but was mostly absent from the nation's legal texts. This discrepancy was the result of the perpetual switch from authoritarianism to democracy and vice versa. As a result, the PPO was never formalized until the enactment of the Crown's CCP of 1832,11 when it first appeared as a means to "safeguard society."12 In the Judiciary Chapter, the 1891 Constitution includes a reference to the Public Prosecutor but makes no mention of the Ministério Público; in other words, the institution's powers and duties were never adequately described. This situation remained until the 1934 Constitution, when the PPO was —for the first time— properly defined. According to this document, the Public Prosecutor would be established "in the Union, in the Federal District and in the Territories pursuant to federal law; and in the States pursuant to local laws."13 With the enactment of the 1946 Constitution, the PPO figure was further delineated, including a special Chapter outlining the Ministério Público, its functions and organization. During the last dictatorship in Brazil (1964-1985), all constitutional powers granted to the PPO were annulled and the office became an extension of the Executive branch. This changed, however, with the enactment of the 1988 Constitution in which the PPO was restructured on the basis of unity, indivisibility and functional independence.14

In Chile, the PPO did not come into existence until 1925, after the enactment of eight different Constitutions. Although the PPO was stated by name, its functions and duties were not mentioned until reforms to the 1980 Constitution were introduced in 2000. In the 1925 Constitution, the PPO was designated as part of the judicial branch, since it only appeared in relation to judges.15 The first CCP was drafted in 1894 but not enacted until 190616, nearly a century after Chile's war of independence. In this code, diverse functions of the PPO and the Promotores Fiscales were defined. As noted earlier, scarce attention was paid to the institution itself. To complicate matters, a 1927 presidential decree abolished the PPO in the first instance, that is, from this year on the PPO's participation was not necessary, and victims were due to present their cases directly to the judge in the Supreme Court or Appeal Court, effectively eliminating PPO's criminal and civil powers and transferring all authority to a single judge. According to the 426 Decree, the PPO was deemed superfluous and, for this reason, its powers and functions were transferred to judges sitting on the Supreme and Appeal Courts.17 This situation remained until 2000, when the institution, its structure, location and duties were included as part of the Constitution18, making it one of the most modern institutions in both Chile and Latin America. At this time, the 1906 CCP was replaced and a PPO Organic Law19 promulgated. After 2000, the PPO became a constitutionally autonomous entity responsible for prosecuting and investigating crimes, exercising criminal action and offering protection to crime victims and witnesses.20

In Mexico, the figure of Ministerio Público during the first years of independence was highly similar to what it had always been in colonial times, with no distinction between entities responsible for prosecuting and adjudicating crimes. Both the 1824 and 1857 Constitutions placed the PPO within the Judicial Branch,21 but never fully specified its powers and functions. In fact, they appeared virtually identical to activities realized by the lower courts. In the words of Hernández Pliego, "the real functions of the PPO were not known and defined until the enactment of the Public Prosecutor Organic Law in 1903 under Porfirio Díaz."22 This law defined the PPO not as an "assistant the criminal courts, but as an active party in trials, responsible for initiating criminal prosecutions on behalf of society."23 The PPO, however, did not realize this duty on an exclusive basis, since prosecutors were still subject to orders issued by tribunals.24 In the 1917 Constitution (and subsequent reforms), the PPO in Mexico was granted exclusive powers to investigate and prosecute crimes with the assistance of police, who remained subject to its control.25 This Constitution placed the PPO within the Executive branch and granted it the exclusive right to file criminal charges.

During the last authoritarian regimes in Brazil, Chile and Mexico (and most other Latin American countries) it can be argued that the PPO operated on the basis of inquisitorial procedures and was located within the Executive or Judicial branch.

III. Analysing the Reforms to Criminal Procedure

1. Brazil

After the military junta fell in 1985, efforts were made to re-direct the nation and put it back on track to democracy. The Constitution of 1988 best expresses this determination to alter the political and judicial framework. It was during this period that many significant efforts were made to change legal assumptions and principles for the sake of fairer and more effective procedures as well as greater respect for international standards and the rule of law. Unfortunately, at that time, few if any of these efforts were codified in the nation's body of law. For example, no significant change was ever made to the Code of Criminal Procedure (CCP) during the first transition years. Amendments were in fact introduced between 2008, 2009 and 201126 to resolve conflicts resulting from a clash between a progressive Constitution and a CCP that, given its inquisitorial nature, reflected values similar to the Italian Rocco Code created under Mussolini's fascist government.27

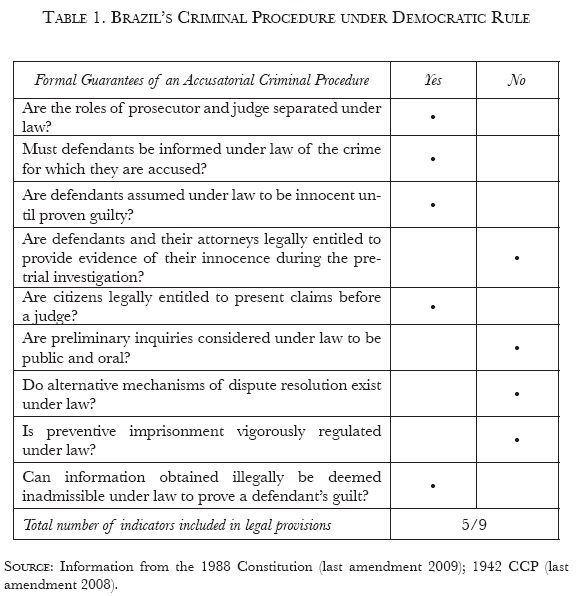

Generally speaking, there are two legal principles upon which Brazilian criminal procedure rest: 1) the 1988 Constitution; and 2) the 1942 CCP (amended version).28 The following table shows how the PPO is now structured and the changes introduced:

Notice that every indicator listed above clearly reflects an accusatorial model. Indeed, mostly all of them have been promoted by judicial reform's projects in Latin America.29 After reviewing an extensive body of literature on the subject,30 I conclude that the nine (9) characteristics listed in Table I may be used to reflect the predominant type of legal system as well as the extent of legal reform. For the sake of analysis, we shall assume that if every indicator (9) listed above appears in a nation's Constitution, laws and regulations, the reform toward an accusatorial system has been fully enacted; if 5 to 8 indicators appear, almost enacted; if 1 to 4 indicators appear, scarcely enacted; and if no (0) indicators appear, not enacted.31

Pursuant to Article 129 of the 1988 Constitution, criminal prosecution is an activity exclusively realized by the PPO, meaning that the judiciary shall no longer, as before, activate the criminal action. For the purpose of criminal prosecution, the 1988 Constitution grants the PPO authority over the judicial police. This means that in every criminal case, the police must comply with the PPO's orders to investigate and present information, at which point the PPO may: 1) request more data; 2) exercise criminal action; or 3) suspend the case. The 11.719 Law enacted in 2008 amended Article 257 of the 1942 CCP to make criminal prosecution a task performed exclusively by the PPO.32

Recent changes to the CPP provide defendants with the right to know the crime for which they are being accused. Accordingly, article 306 states that within 24 hours after imprisonment the authority must inform the defendant the reason of detention as well as the person issuing the accusation.33

With respect to the presumption of innocence, the 1988 Constitution is clear; Article 5, No. LVII states that "No one shall be considered a criminal until a verdict has been issued." Some scholars argue that this right was reinforced34 when Brazil signed the American Convention on Human Rights, also known as the Pacto de San José, which declares in Article 8 that "every individual accused of a criminal offense has the right to be presumed innocent so long as his guilt has not been determined pursuant to law..." Since 1988, all criminal suspects in Brazil have the right to be presumed innocent until otherwise proven guilty.

Brazilian citizens may only take certain cases directly to court.35 It is worth noting that in Brazil two types of criminal actions exist; one public and the other private. The PPO is legally bound to realize public actions; in some cases, it may also realize private action. The difference is that public criminal prosecution occurs only after a crime is officially reported to the police or PPO;36 whereas a private action requires the victim to present the claim.37 Private action may also be exercised when the prosecutor fails to act within the legal term.

Prosecutors are constitutionally obliged to prosecute crimes.38 As a result, there is no opportunity principle39 during the preliminary inquiry; hence the prosecutor is unable to apply alternative mechanisms for the resolution of minor crimes as in many other nations. In Brazil, the only way to resolve conflicts is through adjudication.

Torture, coercion and other types of intimidation are constitutionally prohibited as a means to obtain confession. Article 5, No. III and LVI of the CCP state, respectively: "no one shall be subjected to torture or inhumane or degrading treatment" and "evidence obtained through illegal means shall be inadmissible."

Nothing in the Brazilian Constitution limits the use of preventive imprisonment for serious criminal offenses. The 1942 CCP, Article 312, sets forth the three principles that legitimize preventative imprisonment: 1) as a guarantee to public and economic order; 2) to allow criminal investigations to proceed without restriction; 3) to assure the proper application of criminal law.40 As a result, Brazilian police stations often act as de facto detention centers,41 openly violating the presumption of innocence principle.

In sum, after 20 odd years of transition from authoritarian rule, Brazil has still a path to walk in order to install a legal system with accusatorial procedures. As a result, we can state that the Brazilian reform is almost enacted, as only five (5) of the nine (9) indicators listed above are found in legal provisions. Brazilian criminal procedure contains still several inquisitorial features. As already noted, this situation is the result of a Code of Criminal Procedure similar to that under authoritarian rule; the amendments introduced during the last 70 years have been inadequate to establish an accusatorial model that meets international standards.42

2. Chile

After the fall of General Pinochet's authoritarian regime (1973-1989), President Patricio Aylwin and the newly-elected parliament sought to introduce several reforms to the criminal justice system to match the democratic institutions they were trying to build.43 Leyes Cumplido were instituted to safeguard individual and defendants' rights, as well as to assure that national laws met international human rights standards.44 Although no deep reforms of the criminal justice system were realized during the Aylwin administration (1990-1994), the work done by diverse institutions and organizations45 during this period prepared the way for the "reform of the century," as the transformation of Chilean criminal justice came to be known.

During Eduardo Frei's presidential term, several bills were introduced in the Chilean Congress for approval. These included the new Code of Criminal Procedure; the PPO Organic Law; the constitutional reform reintroducing the PPO in the first instance; and the Public Defense law.46

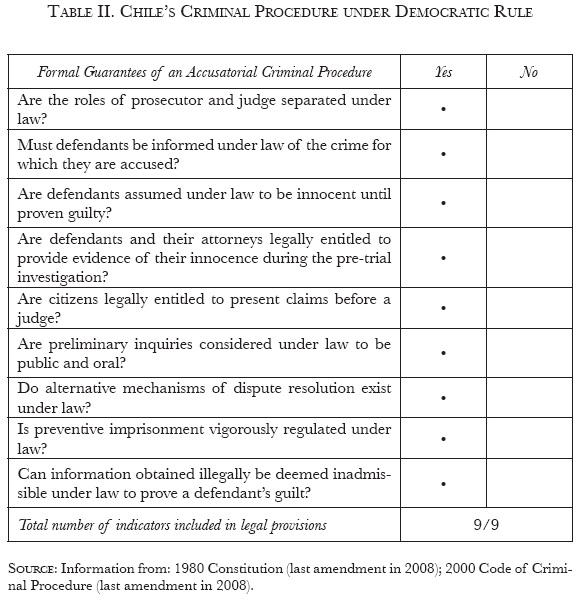

As the following Table shows, these proposals were all eventually enacted into law47, dramatically changing the criminal justice system in Chile:

The Laws 19.696 and 19.519 introduced significant changes both to the 1980 Constitution and Chilean criminal procedure. After more than 70 years, the institution was reintroduced in the first instance as exclusively in charge of criminal investigation and accusation.48 The changes made to criminal procedure were even more significant. In 2000, the passage of Law 19.696 created the new Code of Criminal Procedure (CCP), in which the separation of prosecution and adjudication was clearly delineated. Article 3 states: "Exclusivity of the criminal investigation. The PPO shall be exclusively in charge of conducting investigations of the facts that constitute a crime, those that determine criminal participation and those that prove the defendant's innocence..." Chile started the 21st century under new legal regulations that included the hallmark principle of an accusatorial system, namely, the separation of the investigative and adjudicative functions.

At the moment of their arrest, defendants in Chile now have the right to know why they are being detained; if this is not possible given extraordinary circumstances, this information must be provided when they confront the police or public prosecutor.49 Article 93 grants defendants the right to "be clearly informed about the facts for which they are accused and the rights granted to them by the Constitution and other legal provisions."50 This same Article also provides additional rights to the accused including: (a) assistance of a lawyer starting from the initial stages of investigation; (b) requirement that prosecutors carry out investigations to justify charges against defendants; and (c) the prohibition of torture or other types of cruelty. As can be seen, the accused parties are expected to assume an active role; remain informed about the charges filed against them; and request that prosecutors investigate any facts that may help prove their innocence.

The facts of criminal cases are kept secret to individuals outside the proceedings. Defendants and other parties, however, may examine and obtain photocopies of all records and documents compiled during the investigation.51 This same Article, however, declares that under certain conditions, the prosecutor may order select acts, records or documents to be withheld from the defendant or other related parties for a period up to 40 days.52

In Chile, individuals accused of criminal offenses are presumed innocent until proven guilty. Article 4 of the CCP declares "Presumption of the innocence of defendants: No person shall be considered guilty nor treated as such until a guilty verdict is issued."

Paragraph 4, Article 139 to Article 154 of the 2000 CCP states why and when preventive imprisonment may be justified:53 "All persons have the right to personal liberty and individual security. Preventive imprisonment shall proceed only when other precautionary measures are deemed insufficient by the judge to assure proper investigation or to safeguard either the offended party or society."54 Contrary to what happened prior to reform, the prosecutor must now first formalize the investigation and provide evidence to the judge before applying precautionary measures such as preventive imprisonment.55

Consistent with Article 80-A of the Constitution, the victim may in certain circumstances file criminal charges. In Article 173, the CCP states that "the accusation of any offense may be presented before the police (Carabineros de Chile), investigative police or any competent criminal court, which shall immediately refer it to the PPO." In cases in which the prosecutor decides to discontinue criminal action, the victim or offended party has the right to request that the Ministerio Público reopen proceedings and carry out further investigation. If discrepancies exist between the victim and prosecutor regarding the extent of the defendant's involvement in the alleged crime, the victim or his representative may take the claim to court.

This reform to criminal procedure also included the principle of opportunity. The CCP stipulates the types of cases in which prosecutors (with authorization from the due process judge — juez de garantía) are allowed to discontinue criminal charges. According to Article 170 of the CCP, Chilean prosecutors may decide to discontinue prosecutorial action when the alleged crime (a) does not seriously affect the public interest;56 (b) there is insufficient evidence that the crime was committed; or (c) when the statute of limitations has expired.57 Given the case victims disagree with the discontinuance of the criminal action, they may appear before the due process judge and present their interest on the accomplishment of the prosecution, which obliges the prosecutor to continue the investigation. One important part58 of the Chilean CCP is the introduction of plea-bargaining (Juicio Abreviado) that allows the prosecutor and defense team to agree upon a reduction of charges (solely for minor sentences) in exchange for a guilty plea by the defendant.59 This mechanism may only be applied to criminal cases carrying less than five years of imprisonment. The final decision regarding the plea bargain is made by the due process judge "who has ultimate control over the sentence and responsibility for reviewing the evidence."60 Similarly, Article 237 provides for "conditional suspension of the proceedings;" namely, an alternative way to resolve crimes.61 In order to qualify for conditional suspension of the proceedings, the prosecutor —with the defendant's agreement— must submit a request to the due process judge. This type of alternative dispute resolution is valid only in cases whereby (a) the crime involved is not punishable by more than three years of prison; and (b) the defendant has no prior convictions. Another alternative known as a "restitution agreement" takes place directly between the victims and accused parties. Article 241 states that the defendant and victim have the right to agree on restitution in the presence (and with the approval) of the due process judge. Restitution agreements are valid only for disputes involving personal property, lesser crimes or criminal negligence.

The CCP specifically proscribes certain investigative methods. Article 195 stipulates that criminal suspects shall not be subjected to coercion, intimidation or promise;62 the law forbids all forms of "mistreatment, threats, psychic or corporal violence, torture, deceit, hypnosis or the administration of psycho-medication."

More than 20 years after democratic transition, legal reforms have radically changed the rules of criminal procedure in Chile. These reforms spread beyond the courts into other aspects of criminal justice. For this reason, we can rate the reforms in Chile as fully enacted; namely, every indicator (9) listed above has been codified in the Constitution or the Code of Criminal Procedure. As a result, the Chilean criminal system may be considered fully accusatorial. Nearly 200 years after Independence, Chile has left behind (at least formally) the inquisitorial model bequeathed by the Spaniards.

3. Mexico

The defeat of the PRI in 2000 was a turning point in Mexico's political system; for nearly the entire 20th century, the nation was subject to one-party rule. Although this occurred in the year 2000, this transformation had to some extent63 already started; prior to 2000, the PRI had lost significant power at both federal and local levels.64 The most significant reforms to the criminal justice system, however, occurred in 2008. The Constitution and other legal texts (including the 1932 CCP) were reformed for the purpose of establishing an accusatorial model. This reform included major changes in criminal procedures, including the presumption of innocence and a new police role in investigation.65

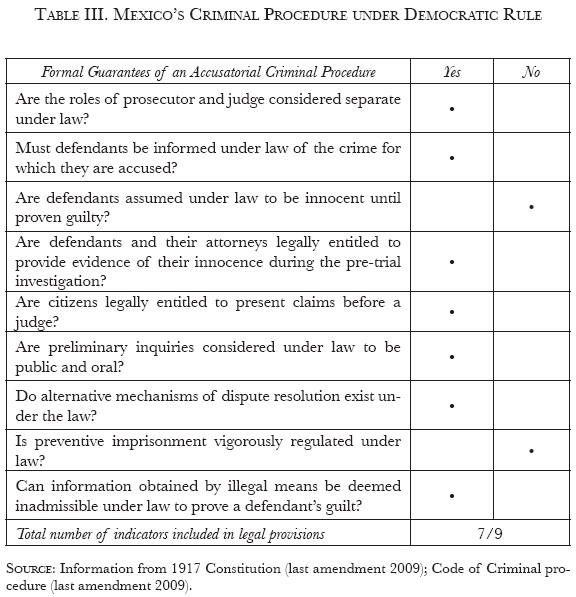

But how significant were these steps toward an accusatorial system? The following Table indicates that many important changes were introduced with the 2008 reform to the criminal system:

As stated above, the 1917 Mexican Constitution clearly separated the accusatory and sentencing functions. In fact, scholars have argued that Article 21 had been misinterpreted, as the PPO claimed exclusive power over all indictments;66 as a result, no individual or entity could challenge the PPO's decision not to press charges or its failure to exercise criminal action.67

The same applies for defendants' right to know the crimes of which they are accused; since the enactment of the 1917 Constitution, this right has existed, though the 2008 reforms strengthened it significantly. In Article 20, Letter B, section III, defendants are granted the right "to be informed, both at the time of their arrest and during their appearance before the PPO or judge, of the facts of the accusation against them and all rights on their behalf."68

The 2008 Constitutional reform also extended defendants' rights during the pre-trial investigation. Article 20, letter B, section I, states that during prosecution, defendants have the right to be presumed innocent until judged guilty in a court of law (Article 20, letter B, section I). An exception, however, is made in cases involving organized crime. A controversial provision introduced in the 2008 reform of Article 16 of the Mexican Constitution (arraigo) openly violates the presumption of innocence by subjecting defendants suspected of organized crime to solitary confinement in so-called high security residences69 for a period of 40 days (with a possible extension of 40 additional days). At the PPO's discretion, the communications of accused parties may be limited to their attorney. As the presumption of innocence principle is not equally applied for all defendants,70 the presence of this indicator is considered negative in Table III.

Article 20, letter B also prohibits torture and coercion as a means of obtaining confessions, which are considered valid only when acquired in the presence of a defense attorney: "confession delivered without the assistance of an attorney shall lack probative value."

Article 20 of the Constitution further states that during the preliminary inquiry, accused parties and their attorneys have the right to see all records compiled by the prosecutor in order to help prepare their defense and offer evidence to rebut charges against them.71 During the investigation, the prosecutor compiles a written dossier that is presented before the judge for discussion in a public oral hearing.

Consistent with Article 19, preventive imprisonment may be used "only when other precautionary measures cannot ensure the appearance of the accused party in court; when the proper realization of the investigation or the safety of the victim, witnesses or community are jeopardized; or when the defendant has been previously sentenced for a premeditated crime." This Article also stipulates that preventive imprisonment may only be applied in cases involving serious crime such as terrorism, organized crime, first-degree murder, treason, and so forth. However, those provisions are severely undermined by the constitutionalization of the arraigo,72 since individuals suspected of participating in organized crime —which according to some recognized scholars and international organizations is poorly defined in the Constitution—73 are to be detained in "pseudo-prisons" (high security residences) while the PPO carries out the investigation. For this reason the presence of this indicator is considered negative in Table III.

With the 2008 reform, several alternative measures for dispute resolution were also introduced.74 For instance, Article 2 of the CCP states that the PPO may facilitate conciliation between the parties involved.

In Mexico, victims are entitled to take their claim before a judge but only in certain cases pursuant to applicable law.75 No further detail is explicitly mentioned in the Constitution. Even before the 2008 constitutional reform, victims had the right to judicial review but only when the prosecutor failed to press charges or decided to discontinue criminal action. This review, however, was limited to the PPO's obligation to investigate, not whether the victim's case would be finally heard in court.

Although the Mexican criminal system has undergone many alterations, the 2008 reform has been the most significant change in over a century. This reform represents a turning point, a historical shift towards a more accusatorial model of criminal procedure. On this basis, we can rate the 2008 reform in Mexico as almost enacted, since seven (7) out of the nine (9) indicators in Table III are now codified in the Mexican Constitution or Code of Criminal Procedure.

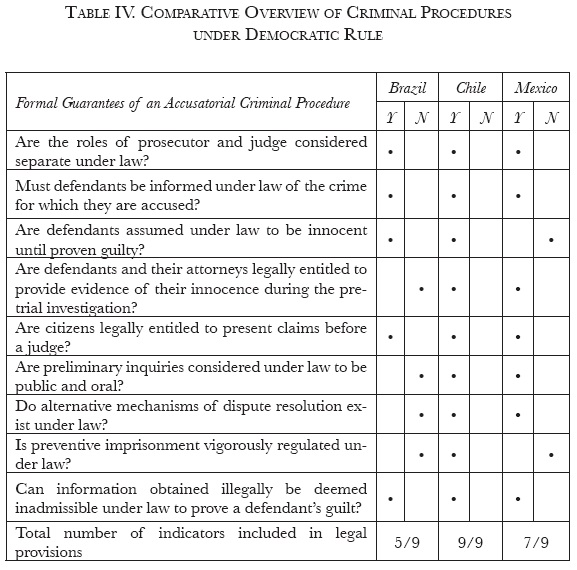

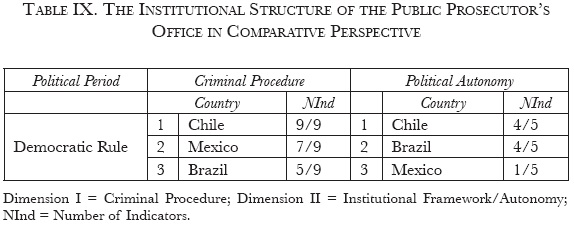

4. Comparative Overview

The criminal justice reforms realized in Brazil, Chile and Mexico vary significantly, especially between Brazil and the other two nations. Chile has undoubtedly made the most significant reforms, but Mexico also took major steps in the same direction. Both countries implemented significant measures to improve victims' rights during the pre-trial phase and defendants' rights during the investigation phase. In the case of Brazil, legislators appeared less than eager to modernize the criminal justice system, despite guarantees included in the 1988 Constitution and later reforms, Brazilian criminal justice contains various inquisitorial (and authoritarian) features. For this reason, we can argue that the reform toward an accusatorial criminal justice system was almost enacted in Brazil, fully enacted in Chile and almost enacted in Mexico.

These reforms occurred at different times relative to the democratic transition period experienced by each nation. In Brazil, reform to some parts of the criminal system occurred mostly in 1988, at the same time the Constitution was enacted. In Chile, two periods of time were critical: 1997 and 2000. In 1997, for example, the PPO was reinstalled in the first instance —in effect, a separation of the prosecution and adjudication functions— after more than 70 years under the umbrella of the judiciary. The year 2000 therefore represents a major shift in the history of criminal justice in Chile, as a new CCP was created after more than a hundred years of rule under a Code that its own drafters criticized as regressive and antiquated.76 For Mexico, the reform was introduced eight years after the end of 70 years of single party rule; as such, it represents one of the most significant changes to criminal procedure in Mexican history.

In all three countries, victims may only file claims directly before courts in certain cases; for instance, when the prosecutor fails to act in a timely manner (Brazil); or when the victim disagrees with the results of the prosecutor's investigation regarding the defendant's involvement (Chile). In none of these countries does the PPO retain the exclusive right to file criminal charges.

Defendants gained additional guarantees regarding the presumption of innocence both in Chile and Brazil; defendants in these countries are now presumed innocent until proven guilty. Although the presumption of innocence was also included in Mexico's Constitution, it does not apply for organized crime-related matters. In all three nations, information obtained illegally (i.e., by torture, intimidation, etc.) may not be used to prove a defendant's guilt. Furthermore, in Chile, prosecutors may not use defendants' confessions as evidence to support or prove their accusations.

In addition, several alternative dispute resolution mechanisms are now formally available to defendants in both Chile and Mexico during the pre-trial investigation. In Chile, for example, the prosecutor may consider alternative dispute resolution in exchange for a defendant's guilty plea, whereas in Mexico, prosecutors are allowed to promote conciliation between the parties. In Brazil, however, there is no legal basis for alternative dispute resolution.

IV. Changes to the PPO's Institutional Framework. Consequences for its Autonomy

1. Brazil

By the mid-1980s, political liberalization in Brazil seemed irrepressible. Many actors had been busy organizing and preparing for this transition. The National Confederation of the Public Prosecutors (CONAMP),77 for example, was a very active player throughout this period. Its priority was to restructure the PPO based on democratic principles and, above all, guarantee the institution's autonomy by moving it out of the Executive branch. Activities realized by this organization included surveys of the nation's prosecutors for the sake of (a) discovering what powers and duties they expected of the institution; (b) how the PPO could be re-positioned within the existing political framework; (c) what constitutional guarantees were necessary for prosecutors to adequately perform their jobs; and so forth. According to Professor Nigro Mazzilli, the CONAMP sent 5,793 questionnaires to members of the PPO and received 977 back. Prosecutors were asked whether the PPO should be located within the Executive, Judicial or Legislative Branch or whether it should become an autonomous organ of the State, being this last option the most preferred by prosecutors. Regarding how the Public Prosecutor should be appointed, most prosecutors answering the questionnaire agreed that the Attorney General must be appointed by all prosecutors through a direct election.78

These surveys provided important insights; the results were presented in 1986 at the National Summit of Attorneys General in Paraná, where Members of the CONAMP and other related organizations including the National Association from the Republic's Prosecutors,79 published the Carta de Curitiba,80 an excellent proposal that created a new prosecutorial mechanism based on indivisibility, unity and autonomy.81 Two years later, the Carta de Curitiba served as the basis of the new constitutional re-defining the PPO.

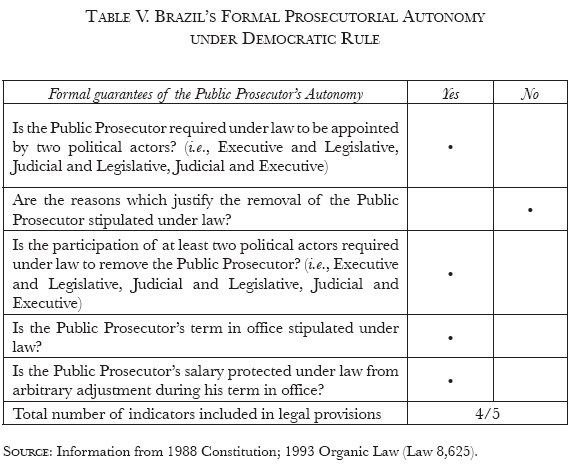

The following table illustrates the changes to the PPO's institutional location following the reforms:

The five (5) indicators in Table V were selected after an extensive revision of academic literature about the judiciary, specifically with respect to its independence.82 Even if the judiciary and public prosecutor's office perform different tasks and are considered distinct institutions, there is no reason they cannot share formal guarantees of autonomy, especially given that the PPO essentially acts as a gatekeeper for the entire criminal justice system. The presence of all 5 indicators in legal provisions shall be evidence that the institutional reform was fully enacted and the PPO fully autonomous; when 3 to 4 indicators are present, then it shall be rated nearly enacted and the PPO nearly fully autonomous; between 1 and 2 indicators shall indicate weak enactment and the PPO weakly autonomous. When no indicator exists, it shall be considered not at all enacted and the PPO not autonomous.83

Article 128, No. 1 of the 1988 Constitution states that "the head of the Public Prosecution of the Union84 shall be the federal Public Prosecutor, appointed by the President of the Republic from among candidates over the age of thirty-five; with the approval of an absolute majority of the national Senate." Thus, after this reform, at least two actors must now participate in the appointment process. The same Article stipulates that the Public Prosecutor's tenure shall be two years (with reappointment allowed).

If the President wishes to remove the Public Prosecutor, the request is now subject to the prior authorization of an absolute majority of the Senate; in other words, the President may no longer unilaterally dismiss the Public Prosecutor it often happened prior to the enactment of the 1988 Constitution.

This said, the Constitution and the 1993 Organic Law fail to stipulate reasons that justify the removal of the Public Prosecutor. Reasons are only set forth in relation to the dismissal of lower ranking members of the judiciary.

The Brazilian 1988 Constitution introduced several provisions concerning the PPO's budget and other financial issues. For instance, Article 127, No. 3 to 6, states that the institution "shall prepare its budget proposal within the limits established in the law of budgetary directives... If the proposed budget fails to conform to these limits... the Executive branch shall make all necessary adjustments for the purpose of consolidation." Article 128, No. 5 of the 1988 Federal Constitution also stipulates that Prosecutors' salaries (including the Public Prosecutor) can never be reduced. Article 129, No. 4 establishes that all salary procedures followed by the PPO must be similar to those established for the Judiciary in Article 93. Prosecutors are granted not only constitutional protection against salary reduction, but salary equivalence to the Judiciary, which represents the top echelon in the Brazilian public service system and serves as a reference for all other public salaries. For this reason, if the Judiciary's pay does not rise, neither do those of any other government worker.85 In sum, the PPO in Brazil has been nearly completely reformed to ensure its autonomy in relation to other branches of the State. We can therefore assert that four (4) out of the five (5) indicators in Table V have been codified either in the 1988 Constitution or in secondary laws. For this reason, the Brazilian PPO can be described as almost fully autonomous.

2. Chile

In the reform of criminal justice, the restoration of the PPO in the first instance is fundamental given the need to separate the prosecutorial and adjudication functions and establish an accusatorial system. After years of discussion,86 the reform that created and defined the general functions, organization and structure of the PPO was finally published in 1997. Law 19.519 introduced a special chapter in the Constitution (Chapter VI-A) which granted the institution notable importance. The first Article of this Chapter stipulates that the institution shall be an autonomous public entity with a hierarchical nature.87 With this Law, the long-standing ambition of separating the roles played by prosecutors and judges was finally achieved.

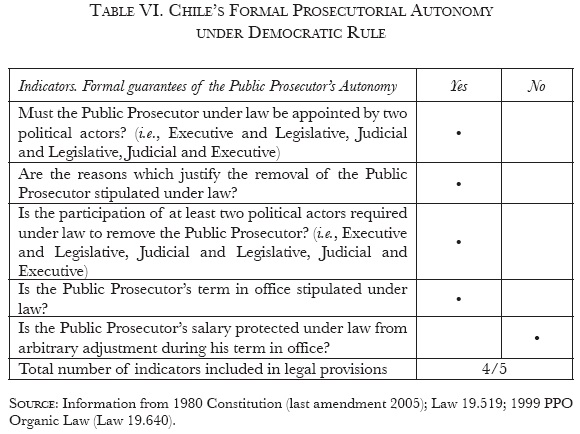

In 1999, Law 19.640 introduced the PPO Organic Law, which provides specific details about the principles that guide the institution as well as how the national and regional prosecutor's offices shall be structured and organized. The Law also establishes how members shall be appointed and removed; and their terms of duration in office. These reforms have been implemented in various stages in all 13 regions of Chile.88 The following Table describes the full extent of the these amendments:

In line with Article 80-C of the 1980 Constitution and Article 15 of the PPO Organic Law, the President of the Republic shall appoint a National Public Prosecutor —with the required approval of 2/3 of the Senate— from five candidates proposed by the Supreme Court. As part of this process, the Supreme and Appeals Courts are required to make a public call for the selection of five candidates whose names are then sent to the President.89 Consequently, three actors actively participate in the selection of the National Public Prosecutor. Since more actors involved in the appointment process increase the autonomy of the appointed position, this has resulted in greater autonomy for the PPO.

The removal of the National Public Prosecutor in Chile requires at least two actors. Article 80-G of the Constitution stipulates that this can be accomplished only by the Supreme Court upon the request of the following actors: 1) the President; 2) the Chamber of Deputies (or ten of its members). The reasons to dismiss the National Public Prosecutor are: a) incapacity; and b) misconduct or proved negligence in developing her/his duties. As a result, the National Public Prosecutor may not be removed from office without the approval of two different institutions and only for reasons stipulated under law.

Article 16 of the PPO Organic Law states that the National Public Prosecutor is appointed to office for a ten-year period; re-election is not allowed. In addition, a special section in the Organic Law establishes a system of remuneration for various levels of public servants working in the PPO. This section, however, fails to prevent the arbitrary reduction of the National Public Prosecutor's remuneration during their term in office, nor specifies the reasons necessary for a reduction. This said, it does require that the National Public Prosecutor's income be equal to that of the President of the Supreme Court.

Since these reforms were implemented, most of the safeguards necessary for prosecutorial autonomy have been codified in law. Based on Table VI, four (4) out of five (5) indicators have been satisfied; for this reason, the reform to the PPO can be called almost enacted, as most guarantees for prosecutorial independence are now formally part of Chilean law. As a result, the Chilean PPO is nearly autonomous.

3. Mexico

The 1917 Constitution made the PPO dependent on the Executive branch not only because legislators at that time failed to envision any compromise in its independence,90 but also because the judicial branch had few active supporters. At that time, legislators were pre-occupied with separating the investigation, accusation and sentencing functions, as all these duties had been traditionally assumed by a judge with the prosecutor acting as assistant.91

Despite a long democratic transition period in which several reform packages were introduced, no significant change to the PPO's institutional location was ever realized. The most significant reform occurred in 1994, when President Ernesto Zedillo sent a proposal to Congress modifying the way in which the Attorney General was appointed to office.92 This reform failed to significantly change anything, however, as the Attorney General could still be dismissed at the sole discretion of the President.

After the PAN won the presidency in 2000, many proposals have been submitted by legal scholars and others to change this situation; up to now, however, no legislation has been enacted. At this time, a proposal awaits discussion in the Chamber of Deputies. This proposal involves the creation of two distinct entities: 1) the Fiscalía General del Estado, a constitutionally autonomous public entity outside of any State Branch and responsible for criminal investigation and prosecution; and 2) the Ministerio Público, an organ of social representation in federal judicial processes and dependent on the Executive branch.93

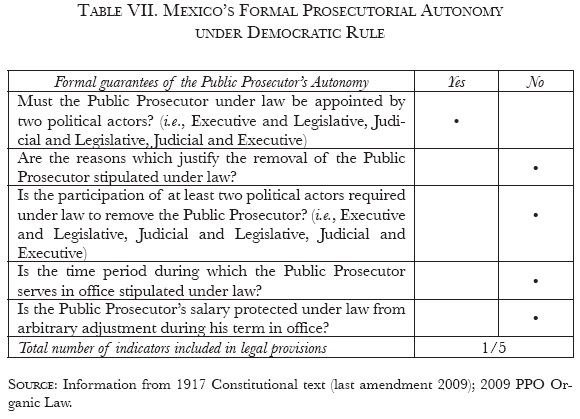

As shown in Table VII, the institution is still dependent on the Executive which have several consequences for the PPO's autonomy:

In the 1917 constitutional text (last amended in 2009), the PPO is addressed in the Judicial Chapter. Article 102 of the Constitution, however, grants the Executive and the Legislative Branch the possibility to appoint the public prosecutor: "The Federal Public Prosecutor's Office shall be headed by the Attorney General [Procurador General de la República), whose appointment shall be made by the Executive with the ratification of the Senate (2/3 majority) or the Permanent Commission during Congressional recesses."94 These prerequisites, however, do not apply for dismissal. As a result, the President of the Republic is entitled to remove the Attorney General at his sole discretion. This fact severely undermines the autonomy of the PPO; if the President of the Republic is not satisfied for any reason with the Attorney General, he or she can be easily replaced. Neither the Constitution nor any other law or regulation specifies reasons for the removal of the Attorney General; the Constitution only states, in Article 102, letter A, that the "President can freely remove the Attorney General."

In addition, no legal texts mention the duration of the Attorney General's term in office; even if these existed, they would make little sense given that the President has complete discretion to remove him or her at any time. During the last two presidential terms, for example, four prosecutors (two for each administration) served in office; when the last Attorney General was removed, the President didn't even explain why.

Similarly, no provision exists to safeguard the Attorney General's salary; or protects the entity's financial autonomy (as in Brazil or Chile).

In sum, Mexico has not yet made any serious efforts to confer autonomy to the PPO. Only one (1) out of the five (5) indicators listed in Table VII has been met. For this reason, Mexico's reform toward prosecutorial autonomy can be characterized as weakly enacted. As noted above, although the biggest problem remains the procedure used to dismiss the Attorney General office's lack of tenure and salary protection are also major issues.

4. Comparative Overview

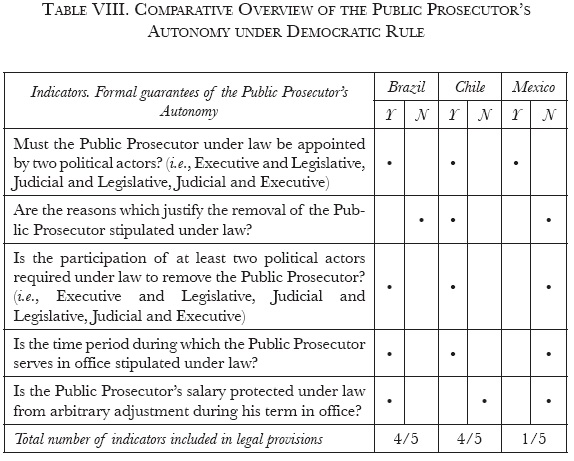

After the reforms, the PPO's in Brazil and Chile have been placed outside traditional State powers. They are now constitutionally autonomous entities that boast functional and budgetary independence. The 1980 Chilean Constitution (amended version) and the 1988 Brazilian Constitution devoted a special Chapter to the PPO in which its prosecutorial structure, duties and restrictions are clearly delineated. In the case of Mexico, however, no important reforms have yet been introduced; the PPO is still located within the Judiciary Chapter and all powers to appoint and remove high-ranking members belong to the Executive branch.95 In fact, the Mexican Constitution contains only one Article (102) that addresses the PPO's institutional framework; whereas both the Brazilian and Chilean constitutions devote an entire special chapter. The most significant differences between the nations involve removal and tenure; both have already passed in Brazil (1988) and Chile (1997), whereas in Mexico they are still awaiting discussion by representatives of the National Congress.

Pursuant to Table VIII, Chile and Brazil have taken greater steps to reform the institutional framework of the PPO, as four indicators are already codified in their respective constitutions. Mexico is in last place, satisfying only one out of the five listed criteria. It can thus be argued that reform of the PPO's institutional framework has been nearly fully enacted in both Brazil and Chile but only weakly enacted in Mexico.

In all three countries, the appointment of the Public Prosecutor is made by at least two actors: the President and the Senate. In the case of Chile, this procedure is enhanced by the participation of the Supreme Court, which is responsible for sending the list of eligible candidates to the President. In Brazil, the President is required to choose the Public Prosecutor from the ranks of the PPO; this selection must then be approved by the Senate. In Mexico, the President chooses any attorney he trusts, and submits this proposal to the Senate for its approval; the candidate is not required to be part of the PPO but rather have a law degree and 10 years' experience in the practice of law.

In Brazil and Chile, the Public Prosecutor may be removed only with the participation of two actors: the Senate at the request of the President (Brazil); or the Supreme Court at the request of the President or House of Representatives (Chile). Only in Chile are reasons for the prosecutor's dismissal clearly stipulated in the Constitution. In Mexico, only one actor (the President) is required to dismiss the Public Prosecutor; this may be done without any specific reason, as the motives for removal are not specified in the Constitution or any other legal text.

In Mexico, the Public Prosecutor's term in office is not specified in any provision; he or she may be removed from office at any time at the sole discretion of the President. On the contrary, tenure is assured in Chile and Brazil; public prosecutors are appointed for a ten (10) year-period without the possibility of reappointment (Chile) and for two (2) years with (an unspecified) possibility of reappointment (Brazil).

In conclusion, only Brazil protects the Public Prosecutor's salary in accordance with law. In the case of Chile, an entire section sets forth in detail the PPO's budgetary matters and financial organization; but no protection is granted to the Public Prosecutor's salary.

V. Concluding Remarks: Comparison of Reforms to the PPO in Brazil, Chile and Mexico

Reforms to the PPO differ across nations. Chile shows more changes regarding the criminal procedure and the political autonomy of the PPO than Brazil and Mexico. It fully adopted an accusatorial legal system and granted constitutional autonomy to the PPO; in other words, the reforms changed nearly every feature that needed change, enabling higher levels of autonomy for both the Prosecutor and the PPO. In sum, Chile had a solid head start before initiating work to strengthen and consolidate the rule of law.

With respect to the PPO's autonomy, Brazil and Chile reformed three more elements than Mexico. The aspect with fewest changes was criminal procedure. In comparison to the other two nations, Brazil instituted few modifications of the inquisitorial nature of its justice system; in contrast, major advances were made in Mexico and Chile. The inquisitorial nature of criminal procedure in Brazil remains the Achilles' heel of reforms to the PPO in that country. This in spite of the fact that guarantees would confer real advantages to Brazilian citizens and users of prosecution services, in particular defendants; among these would be the possibility of alternative mechanisms for dispute resolution.

Mexico implemented two more accusatorial elements than Brazil, but two less than Chile. The steps taken by Mexico to reform its criminal system have been noteworthy. This said, Mexico still rates poorly with respect to the PPO's autonomy; Mexican politicians have yet to take any necessary steps to achieve autonomy for prosecutors. As a result, the nation boasts of only one (1) out of five (5) prosecutorial guarantees. For this reason, many important issues must be first addressed before change is realized in the Public Prosecutor's dependence on the President (it is worth noting here that the appointment of Mexican public prosecutors at the local level also relies on the local Executive). A crucial step toward prosecutorial autonomy would be to change the way in which Public Prosecutors are dismissed by requiring the participation of more actors in the decision-making process, as well as clearly specifying the reasons required for dismissal.

Although Brazil, Chile and Mexico have made undeniable progress in reforming the structure, procedures and duties of the PPO, various critical issues still remain unresolved for both Mexico and Brazil. These elements must still be faced by elected officials and other actors to help re-formulate rules that would enhance the criminal justice system and strengthen the rule of law. In either case, the scenario offered by these countries suggests that elected officials are gradually realizing that democracy means more than just elections and that a modern system of justice requires more than independent judges and oral trials.

* Ph.D. in Political Science from the Italian Institute of Human Sciences, University of Florence and presently research-professor at Instituto Tecnológico de Estudios Superiores de Occidente (ITESO), Guadalajara.

1 See National Commission of Truth, Report of the Chilean National Commission on Truth and Reconciliation (Oct. 4, 2002), available at http://www.usip.org/files/resources/collections/truth_commissions/Chile90-Report/Chile90-Report.pdf. [ Links ] Piedrabuena, Guillermo, Función del Ministerio Público en la realización del Estado de derecho en Chile, Revista de Derecho (1999). [ Links ]

2 Roberto Hernández & Layda Negrete, El túnel: justicia penal y seguridad pública en México (2005). [ Links ]

3 Daniel Brinks, The Judicial Response to Police Killings in Latin America. Inequality and the Rule of Law (Cambridge University Press, 2008). [ Links ]

4 Given that Brazil and Mexico are federal countries while Chile is unitary, reforms to the PPO analyzed here were introduced nationally in order to control for variation that might occur at the state level in either country.

5 Mauricio Duce & Rogelio Pérez Perdomo, Citizen Security and Reform of the Criminal Justice System in Latin America, in Frühling Hugo, Joseph S. Tulchin & Heather A. Golding (eds.), Crime and Violence in Latin America. Citizen Security, Democracy and the State (The Woodrow Wilson Center, 2003, 71). [ Links ]

6 Alberto Binder, Funciones y disfunciones del Ministerio Público penal, 9 Revista de Ciencias Penales (1994), available at http://www.cienciaspenales.org/revista9f.htm (Last visited May, 2008); [ Links ] Julio Maier, Derecho Procesal Penal (1996). [ Links ]

7 See Guillermo Colín Sánchez, Derecho mexicano de procedimientos penales 112 (Porrúa, 1964). [ Links ]

8 The Brazilian Ministério Público is currently the institution that investigates and prosecutes crimes. In Brazil it emerged as the institution in charge of protecting the interest of the Portuguese crown that during the first years of the 19th century was established in this country.

9 The main concern of political leaders at the time was to redesign the State and (often) fight either internal or external wars to maintain power or define territory.

10 According to José María Rico, the legal system adopted by Latin American countries after their independence wars was mixed, but the inquisitorial features were predominant de facto; that is, in reality, the system was inquisitorial. See José María Rico, La administración de la justicia en América Latina. Una introducción al sistema penal (Centro para la Administración de la Justicia, 1993). [ Links ] On the other hand, Duce and Riego argue that the legal system adopted by Latin American countries was inquisitorial and no country (except Cuba and Puerto Rico) followed the system proposed by the Napoleonic Code d'Instruction Criminelle. See Mauricio Duce & Cristian Riego, Introducción al nuevo sistema procesal penal (Universidad Diego Portales, 2002). [ Links ]

11 The Constitution of 1824 only mentioned the Tribunal de Relafao and the Crown's Prosecutor who was in charge of diverse functions, including the prosecution of criminal cases.

12 Victor Roberto Correa de Souza, Ministério Público: aspectos históricos, Jus Navigandi, 2003, available at http://jus2.uol.com.br/doutrina/texto.asp?id=4867. [ Links ]

13 See João Gualberto Garces Ramos, Reflexões sobre o Ministério Público de ontem, de hoje e do 3o. Milenio, 63 Justitia 51, 51-75 (2001). [ Links ]

14 Unity refers to the fact that members can have only one institutional affiliation; indivisibility to the possibility of members being substituted among them; and functional independence refers to members of the institution being protected from external influences. See María Tereza Sadek & Rosangela Batista Cavalcanti, The New Brazilian Public Prosecution. An Agent of Accountability, in Democratic Accountability in Latin America 201-27 (Scott Mainwaring & Christopher Welna eds., Oxford University Press, 2003). [ Links ]

15 Chilean Constitution.

16 Duce & Riego, supra note 10, at 54.

17 Decreto con Fuerza de Ley 426, art. 1, 2 (1927).

18 See Mauricio Duce, Criminal Procedural Reform and the Ministerio Público: Toward the Construction of a New Criminal Justice System in Latin America (Thesis Submitted to the Stanford Program in International Legal Studies at the Stanford Law School, Stanford University, 1999); [ Links ] Rafael Blanco, La reforma procesal penal en Chile. Reconstrucción histórico-política sobre su origen, debate legislativo e implementación (2005), available at clashumanrights.sdsu.edu/Chile/libro_historia_de_la_reforma.doc (last visited May 2008). [ Links ]

19 An "Organic Law" is a secondary law created in order to organize a public service or an institution.

20 Chilean Constitution, art. 80-A.

21 See Juventino Castro, El Ministerio Público en México. Funciones y disfunciones (Porrúa, 2008). [ Links ]

22 Julio Antonio Hernández Pliego, El Ministerio Público y la averiguación previa en México 16 (Porrúa, 2008) [ Links ]

23 Jesús Martínez, Glosario procesal del Ministerio Público. Pruebas, conclusiones y agravios 46 (Porrúa, 2009). [ Links ]

24 Reforms introduced in 1900 removed the PPO from the judiciary and made it part of the executive branch. From 1900 on, the Executive was responsible for appointing the Federal Public Prosecutor. See Héctor Fix-Zamudio, Función constitucional del Ministerio Público. Tres ensayos y un epílogo (IIJ-UNAM, 2004). [ Links ]

25 Mexican Constitution, art. 21.

26 Laws that introduced more changes to the 1942 CCP included Law 10.792 of 2003 but especially Laws 11.689, 11.690 and 11.719 of 2008. There was a total number of 48 Laws or Decrees that have amended the CCP since 1942 to 2009 (CCP 1942, last modification 2009).

27 See Eugénio Pacelli, Curso de Processo Penal (Lumen Júris, 2008). [ Links ]

28 The Code of Criminal Procedure used here was last amended in January 2009.

29 For more information, see Linn Hammergren, Envisioning the Reform. Improving Judicial Performance in Latin America (The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2007). [ Links ]

30 John Henry Merryman, The Civil Law Tradition. An Introduction to the Legal Systems of Western Europe and Latin America (Stanford University Press, 1985); [ Links ] Alberto Binder, La justicia penal en la transición a la democracia en América Latina, Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes, Alicante, http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/FichaObra.html?Ref=14381&portal=157 (1994); [ Links ] Mirjan Damaska, The Faces of Justice and State Authority. A Comparative Approach to the Legal Process (Yale University Press, 1986); [ Links ] Carlo Guarnieri, Pubblico Ministero e Sistema Politico (Casa Editrice Dott. Antonio Milani, 1984); [ Links ] Máximo Langer, Revolution in Latin American Criminal Procedure: Diffusion of Legal Ideas from the Periphery, 55 The American Journal of Comparative Law 617, 617-76 (2007); [ Links ] Mattei Ugo & Luca G. Pes, Civil Law and Common Law: Toward a Convergence?, in The Oxford Handbook of Law and Politics (Daniel Kelemen & Gregory Caldeira eds., Oxford University Press, 2008). [ Links ]

31 Please note that this mode of observing the shift from an inquisitorial into an adversarial model is entirely de iure and not de facto; in other words, based on the indicators listed in Table I, we do not know whether these reforms are being implemented or not, but only if an adversarial model has been introduced in the Constitution or other legal texts.

32 Before the amendment, the article only said that "the PPO shall promote and supervise the execution of law," Brazilian CCP (1942). See also Art. 257, 11.719 Law (2008).

33 Law 12,403 that introduced modifications to the 1942 CCP, 2011, available at www.plan-alto.gov.br/ccivil. I thank Professor Eliezer Gomes da Silva from University of Pernambuco for this remark.

34 Some authors claim that the 1988 constitutional assembly did not want to fully embrace the right of presumption of innocence and, for this reason, the statement not culprit appears in Article 5, No. LVII rather than the latter term. See Antonio Gomes Filho, O Principio da Presunção de Inocência na Constituição de 1988 e na Convenção Americana sobre Direitos Humanos, 42 Revista do Advogado 30, 30-4 (1994). [ Links ]

35 Cases regarding crimes against honor, rape, harassment and the corruption of minors may be denounced by claimants but only if the PPO fails to activate the case within the stipulated period.

36 Art. 5, Brazilian CCP (1942).

37 The type of crime requiring private action include harassment, rape, corruption of a minor, or crimes against honor.

38 Except for those crimes that require private action. In this case, as mentioned above, the PPO must wait for the victim to first report the crime.

39 The principle of opportunity refers to the discretion that a prosecutor has to decide not to prosecute a crime in which, for example, defendants guilt is not relevant and then apply an alternative mechanism of dispute resolution. It opposes to the principle of legality by which a prosecutor must compulsorily prosecute all crimes.

40 Art. 312, Brazilian CCP (1942) —amendment introduced in 1967—. There is much controversy around the first of these three circumstances, given that it conflicts with the constitutional right of "not guilty until proven otherwise." See Pagelli, supra note 27.

41 A further consequence of this fact is the worsening of prison conditions and the overpopulation of penitentiaries. Indeed, Brazil is world famous for the conditions of its penitentiaries. According to a report on Brazilian criminal justice issued by the International Bar Association "many people are imprisoned irregularly (and) spend years in pre-trial detention... judges use their broad discretionary powers under Brazilian law to order mass pre-trial detentions." See International Bar Association Human Rights Institute. One in Five: The Crisis in Brazil's Prisons and Criminal Justice System (The Open Society Institute, 2010). [ Links ]

42 Although the Senate approved a new Project Code of Criminal Procedure in December 2009, it is still awaiting discussion in the National Congress.

43 In Chile, as in nearly all Latin American countries, the judiciary was the first institution to be reformed after the breakdown of authoritarianism. For the Chilean case, see Lisa Hilbink, Judges Beyond Politics in Democracy and Dictatorship. Lessons from Chile (Cambridge University Press, 2007). [ Links ]

44 See Garlos de la Barra Gousino, Adversarial vs. Inquisitorial Systems: The Rule of Law and Prospectsfor Criminal Procedure Reform in Chile, 5 Southwestern Journal of Law and Trade in the Americas 323, 323-64 (1998). [ Links ]

45 For instance, Corporación de Promoción Universitaria, Citizen Peace Foundation and USAID; academics and professional lawyers' organizations, as well as the bar association established a Technical Commission in charge of collecting agreements based on the discussions and design of new procedural rules. See 1 Lennon Maria Horvitz & Julián López Masle, Derecho procesal penal chileno 21 (Editorial Jurídica de Chile, 2002). [ Links ]

46 See id. at 23.

47 Law 19.696 (2000) created the new Code of Criminal Procedure; Law 19.649 (1999) created the PPO Organic Law; Law 19.718 (2001) created the Public Defender; Law 19.519 (1997) introduced several amendments to the Constitution to restore the PPO in the first instance.

48 Chilean Constitution, art. 80-A (1980), last modification 2009.

49 Furthermore, this article stipulates that four matters shall be recorded in the police station: 1) that information was provided to the defendants about why they have been arrested and their respective rights; 2) the way in which this information was provided; 3) the person who solicited the information; and 4) the individuals present during this act. Chilean CCP, art. 135 (2000).

50 Chilean CCP, art. 93 (2000).

51 Chilean CCP, art. 182 (2000).

52 The defendant or any other intervening party may request that the due process judge end or limit the amount of time documents or records are normally kept in secret. See id.

53 The Law 20.074 in 2005 and Law 20.253 in 2008 recently introduced reforms to the section of preventive imprisonment.

54 Chilean CCP, art. 139 (2000).

55 Chilean CCP, art. 230 (2000).

56 A crime that does not endanger the public interest is considered minor, which implies sentences of less than 18 months in prison. The same article also states that this rule does not apply for criminal offenses or wrongdoings committed by public servants.

57 See Blanco, supra note 18.

58 Law 19.806 and Law 20.074 recently reformed this article in 2002 and 2005 respectively.

59 Article 406 points out when the victim can oppose the procedimiento abreviado.

60 See Rafael Blanco, Richard Hutt & Hugo Rojas, Reform to the Criminal Justice System in Chile, 2 Loy U. Ghi Int'l L. Rev. 253 (2006). [ Links ]

61 Law 20.074 and Law 20.253 recently reformed this article in 2005 and 2008 respectively.

62 Promise refers to the prosecutor offering something in exchange to the defendant if he declares his responsibility on the crime. I sincerely thank Christian Cuevas for this explanation.

63 In this regard, the judiciary was reformed in 1994 and independence granted to Supreme Court justices; the Electoral Federal Institute (IFE) was created in 1996 as an autonomous organ in charge of overseeing electoral processes; a National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) was instituted in 1990 and later (1999) transformed into an autonomous organ; and finally, the Electoral Tribunal of the Federal Judiciary was established to fully and irrevocably resolve challenges to electoral results.

64 During 1988 presidential election, the PRI faced a competitive process; it held on to the presidency despite widespread fraud claims by opposition parties. During this process, the PRI acknowledged that the left-center coalition known as the National Democratic Front (FDN) had won four seats in the Senate —the first time that opposition party representatives were accepted into this chamber. A year later, an event that marked the beginning of the PRI's fall from power was when it accepted the loss of the state governorship of Baja California.

65 The Federation, States and Federal District have a period of eight years to adapt their Constitutions and laws to the reforms introduced to criminal procedure by the Decree that amended Articles 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 and 22 of the Constitution (Mex. Const. transitory art. 2). See also Matt Ingram & David A. Shirk, Judicial Reform in Mexico. Toward a New Criminal Justice System (Transborder Institute-University of San Diego, 2010). [ Links ]

66 See Sergio García Ramírez, Consideraciones sobre la reforma procesal penal, in Retos y perspectivas de la procuración de justicia en México 57 (Miguel Carbonell coord., IIJ-UNAM, 2004). [ Links ]

67 As stated above, this monopoly was broken by a 1994 reform package that introduced judicial review for cases in which prosecutors decide not to prosecute crimes.

68 This article also states that in cases involving organized crime, the judge may decide to keep the accuser's name in reserve.

69 High security residences are special detention houses where organized crime suspects are kept while under investigation.

70 As a matter of fact, several months before the reform was passed, the Mexican Supreme Court stated in a jurisprudential thesis (XXII and XXIII/2006) that the arraigo was unconstitutional because it violated personal and transit liberty guaranteed by the Constitution in articles 16,18,19,20 and 21. With its decision the Supreme Court established that persons against which the arraigo is used can avoid the measure through an Amparo writ. See Pleno de la Suprema Corte de Justicia [S.C.J.N.] [Supreme Court], Semanario Judicial de la Federación y su Gaceta, Novena Época, tomo XXIII, Febrero de 2006, Tesis no. P. XXII/2006 (Mex.).

71 This article also mentions that some cases withholding information may be justified in order to facilitate the success of the investigation.

72 I thank Professor Gerardo Ballesteros and the MLR reviewer for this remark.

73 See generally Amnesty International, Reformas al sistema de justicia penal: avances y retrocesos, Public Statement (2008), available at http://amnistia.org.mx/contenido/2008/02/08/reformas-al-sistema-de-justicia-penal-avances-y-retrocesos/ (last visited Oct., 2010); [ Links ] Miguel Carbonell, Los juicios orales en México (Porrúa-RENACE, 2010). [ Links ]

74 These measures were introduced especially for the trial phase. In this respect, Article 27 of the 1932 Criminal Code (last amended in 2009) sets forth several alternative mechanisms for dispute resolution which can be grouped into three sections: 1) probation, including labor, education and rehabilitation aimed at socially reintegrating the convicted; 2) semi-release, or alternating periods of probation and imprisonment; and 3) community work, or non-paid labor in public education or social assistance programs.

75 Mex. Const. art. 21.

76 See Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional, Historia de la Ley 19.696. Establece el Código Procesal Penal (2000). [ Links ]

77 The Confederação Nacional dos Membros do Ministerio Público is an institution of prosecutors from every Brazilian State founded to improve the PPO's performance and enhance the professional careers of prosecutors. See Histórico da CONAMP, available at http://www.conamp.org.br/outros/historico.aspx (Last visited Oct., 2011). [ Links ]

78 Hugo Mazzilli, O Ministério Público na Gonstitutição de 1988 (Editora Saraiva, Brazil, 1989). [ Links ]

79 Associação Nacional dos Procuradores da República (ANPR).

80 The Carta de Curitiba took also many of the proposals concerning the PPO from the project designed by the Afonso Arinos Commission —the commission in charge of designing a new Constitution. See Mazzilli, supra note 78, at 30.

81 Carta de Curitiba, art. 2 (1986).

82 See generally William Prillaman, The Judiciary and the Democratic Decay In Latin America. Declining Confidence in the Rule of Law (Praeger Publishers, 2000); [ Links ] Gretchen Helmke, The Logic of Strategic Defection: Court-Executive Relations in Argentina under Democracy and Dictatorship, 96 American Political Science Review 305, 305-20 (2002); [ Links ] Carlo Guarnieri, Giustizia e política. I nodi della Segonda Repubbliga (Il Mulino, 2003); [ Links ] Bill Chávez, Rebecca, The Rule of Law in Nascent Democracies. Judicial Politics in Argentina (Stanford University Press, 2004); [ Links ] Courts in Latin America (Gretchen Helmke & Julio Ríos eds., Cambridge University Press, 2010). [ Links ]

83 Same warning as above: this observation of the change from a dependent to an autonomous PPO is entirely de iure and not defacto; in other words, based on Table IV, one cannot tell if the institution is in reality autonomous.

84 But also of the Federal Public Prosecution.

85 I sincerely thank Professor Eliezer Gomes da Silva from the University of Pernambuco for this remark.

86 Since 1992, the president had sent to the Senate a project to reform the 1980 Constitution and reintroduce to the Chilean criminal justice system the figure of the PPO. Later on, in 1996 Eduardo Frei Ruiz sent to the Senate the project that started the constitutional reform to create the Public Prosecutor. See Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional, Historia de la Ley 19.519. Crea el Ministerio Público (Santiago de Chile, 1997), available at http://www.bcn.cl/histley/lfs/hdl-19519/HL19519.pdf. [ Links ]

87 The project presented by Eduardo Frei includes a brief discussion of the different types of institutional frameworks (Executive, Judicial, Legislative) and their respective shortcomings. His proposal was to create a constitutionally autonomous entity to enhance the performance of the new accusatorial model in which prosecution and adjudication are separated. See id.

88 There were five implementation stages. The first stage took place in 2000 and covered regions IV and IX; the second stage was in 2001 for regions II, III and VII; the third stage was in 2002 and covered regions I, XI, XII; the forth implementation stage took place in 2003 and covered regions V, VI, VIII and X; finally, the five stage in 2004 covered the Metropolitan region. See Andrés Baytelman & Mauricio Duce, Evaluación de la reforma procesal penal. Estado de una reforma en marcha 35 (CEJA-JSCA, 2003). [ Links ]

89 Chilean Constitution, art. 80-E (1980); Chilean PPO Organic Law, art. 16 (1999).

90 Portes Gil, 1932, quoted by Fix-Zamudio, supra note 24.

91 The idea of establishing the PPO as an autonomous public entity was not discussed.

92 After this reform was implemented, the Senate was still expected to approve the President's appointment of the Attorney General.

93 For further details, see IIJ-UNAM, Propuesta de reforma política 19 (2009), available at http://www.juridicas.unam.mx/invest/RefEdo.pdf. [ Links ]

94 Mex. Const., art. 102; Mexican PPO Organic Law, art. 17 (2009).

95 Although the 1917 Assembly in Mexico decided to transfer prosecution services from the Judicial to the Executive branch, they decided to respect the format of the 1857 Mexican Constitution and include Article 102 in the Judicial Chapter. Up to now, no change has been made in this respect; the PPO still appears in the Judicial Chapter; and the appointment and removal of Federal Public Prosecutors is made by the President.