Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Migraciones internacionales

On-line version ISSN 2594-0279Print version ISSN 1665-8906

Migr. Inter vol.1 n.2 Tijuana Jan./Jun. 2002

Artículos

Working on the Margins in Metropolitan Los Angeles: Immigrants in Day-Labor Work

Abel Valenzuela Jr.*

* University of California, Los Angeles.

Abstract

This article explores disadvantage theory for understanding the participation of Latino immigrants in day labor. Data from 481 randomly surveyed day workers at 87 hiring sites throughout Metropolitan Los Angeles make possible an examination of key demographic and labor market characteristics of this self-employed occupation. Even though the overwhelming majority of day laborers are recently arrived and unauthorized immigrants, not all are desperate, as disadvantage theory would have us believe. Day laborers are diverse in terms of their family structure, recency of arrival, tenure in day work, and human capital. Despite this diversity, lack of human capital and other characteristics generally handicap day laborers in their search for stable, better paying occupations in the non-day-labor market. Earnings among day laborers are mixed, hourly rates are higher than federal or state minimum-wage ceilings, bargaining is commonplace and advantageous to the worker, and wages are paid in cash and untaxed. However, these advantages are offset by unstable work patterns. For a minority of day laborers, this market provides an alternative to other forms of low-skilled, and irregular employment.

Keywords: international migration, day labor, disadvantage theory, work, Los Angeles.

Resumen

Este artículo explora la teoría de la desventaja para entender la participación de inmigrantes latinos como jornaleros urbanos. Entrevistas con 481 jornaleros urbanos, seleccionados aleatoriamente en 87 lugares de empleo en el área metropolitana de Los Ángeles, hacen posible un análisis de las características demográficas y del mercado de trabajo de este tipo de auto empleados. Aunque la gran mayoría de los jornaleros urbanos son inmigrantes recién llegados sin autorización para trabajar, no todos están desesperados, como la teoría de la desventaja podría hacernos creer. Los jornaleros urbanos son diversos en términos de su estructura familiar, el tiempo de su llegada, su experiencia en este trabajo y su capital humano. A pesar de esto, la falta de capital humano y otras características, generalmente los obstaculizan para buscar ocupaciones estables y mejor pagadas en el mercado laboral regular. Los ingresos entre los jornaleros urbanos son diversos, la paga por hora es mayor que los topes del salario mínimo federal o estatal, el regateo de salarios es común y ventajoso para el trabajador y los salarios son pagados en efectivo y libres de impuestos. Sin embargo, estas ventajas son neutralizadas por la inestabilidad del trabajo. Para una minoría de jornaleros urbanos este mercado ofrece una alternativa a otros empleos irregulares y de baja calificación.

Palabras clave: migración internacional, jornaleros urbanos, teoría de la desventaja, trabajo, Los Ángeles.

Introduction*

Day labor, the occupation in which men congregate visibly on street corners, in empty lots, or in parking lots of home improvement stores to solicit temporary daily work, is a burgeoning labor market in immigrant-rich cities and regions (Fernández 1999; Gearty 1999; McQuiston 1999; Visser 1999). In Los Angeles and Orange Counties, between 20,000 and 22,000 day laborers, spread over 87 "open-air" hiring sites, seek work on a daily basis (Valenzuela 1999).

According to a Bureau of Labor Statistics survey on the contingent1 workforce in the United States, over 250,000 day laborers may exist nationally (Polivka 1996).2 Other than anecdotal evidence suggesting that these jobs are unstable, and the workers who perform them are overwhelmingly immigrant, male, and desperate, we know little about this occupational niche or the workers who participate in it. Similarly, with the exception of a few case studies and publications on this occupation in the United States (Malpica 1996; Quesada 1999; Valenzuela 1999, 2001; Walter et al. 2002), we know little about the motivations and structures that would explain the preponderance of immigrant men in this line of employment.

Conventional labor theory holds that disadvantage in the labor market (Light 1979; Min 1988) explains the participation of workers in day labor. Labor theory posits that disadvantage leads to the unequal participation in entrepreneurship and self-employment of different groups of workers. Latino immigrants, by virtue of their tenuous status in the formal labor market, their racial and ethnic background, their low levels of human capital, and their largely unauthorized status, participate at higher rates than non-immigrants and other racial or ethnic groups. According to disadvantage theory, difficulties in the general labor market encourage entrepreneurial activities and other forms of self-employment, such as domestic work (Hondagneu-Sotelo 1994a, 2001), and alternative income-generating activities, such as day labor (Valenzuela 2001), street vending, and informal market activities (Williams and Windebank 1998; Castells and Portes 1989).

This article uses data from the Day Labor Survey (DLS)3 to explore how disadvantage theory explains the participation of immigrant workers in day labor. The article contributes to a better understanding of day labor, the variety of workers of this market, and the nature of their participation in it. After briefly discussing day-labor work, I discuss in detail disadvantage theory and its utility for explaining unequal rates of participation in entrepreneurial and other forms of self-employment. I then describe the research and data used to explore day labor. I next examine key demographic, social, and labor-market characteristics of this labor exchange, paying particular attention to four factors that explain Latino immigrant participation in day labor, including important labor-market advantages (that is, experience and flexibility) that compel immigrants to participate in this line of work. I conclude by discussing the implications of these findings and the application of disadvantage theory for explaining participation in day labor, including the framework's inability to account for why some experienced (for example, long-term, educated), and hence less disadvantaged, workers enter the day-labor market.

Working Day Labor

The contemporary origins of day labor and other occupations, such as domestic work (Rollins 1985; Romero 1992; Hondagneu-Sotelo 1994a, 2001) and work paid "under the table," are related to global economic activities and large-scale immigration to areas such as New York, Miami, Chicago, and Los Angeles. The expansion of global informal markets and the decline of state-regulated formal economic activity (Castells and Portes 1989) have also contributed significantly to the growth of these occupations. The restructuring of the economy, particularly that related to formal economic activities and occupations related to part-time or contingent work (Sassen-Koob 1985; Belous 1989; Tilly 1996; Carnoy, Castells, and Benner 1997) also help explain the recent growth of day labor. We know that self-employment and entrepreneurship is growing rapidly (Gartner and Shane 1995; Light and Rosenstein 1995), subcontracting prevails over union contracts in various industrial sectors, and the cash economy is expanding in the microeconomic realm, while trade is increasingly becoming a crucial feature of international exchange (Portes, Castells, and Benton 1989). These factors help us understand the modern-day development of this occupation.

Day labor, however, is not new to the global or U.S. labor force. The practice of men and women gathering in public settings in search of work dates back to at least medieval times when the feudal city was originally a place of trade. In England during the 1100s, people seeking work assembled at daily or weekly markets (Mund 1948:106). Statutes regulated the opening of public markets in merchant towns and required agricultural workers (foremen, plowmen, carters, shepherds, swineherds, dairymen, and mowers) to appear with tools to be hired in a "commonplace and not privately" (Mund 1948:96). The City of Worchester created an ordinance that required laborers to stand "at the grass-Cross on the workdays...ready to all persons such as would hire them to their certain labor, for reasonable sums, in the summer season at 5:00 a.m. and the winter season at 6:00 a.m." (Mund 1948:100-101).

In the United States, as early as the late 1700s, Irishmen were indentured to the Potomac Company of Virginia to dig canals throughout the northeast alongside free laborers and slaves. A casual labor force proved to be more viable financially than indentured servants and slaves because the former could be laid off in economic downturns while the latter had to be provided with food and shelter. Casual wage laborers worked by the year, month, or day (Way 1993). During the early to mid-1800s, day laborers were recruited from construction crews or worked for track repairmen of railroad companies. Casual laborers (often laid off from construction jobs) worked in a variety of unskilled positions (brakemen, track repairmen, stevedores at depots, emergency firemen, snow clearers, or mechanic's assistants). Some of these workers were recent immigrants—Chinese and Mexicans in the west and Germans and Irish in the east (Licht 1983:37, 42, 60). Many day laborers in the west were tied to California's agricultural industry and the Bracero Program after World War II (Schmidt 1964).

Contemporary employers of day laborers benefit similarly from exploiting this market. The ease and rapidity of hiring a day laborer to help with household improvement or repair is an important attraction for homeowners and other individuals who hire day laborers. The market is also extremely attractive to construction subcontractors who need to replace a regular employee who has called in sick or been fired. Besides basic supply-and-demand factors, day laborers are a pliable labor force that can undertake tasks workers in the general economy may not easily or willingly perform. The cost of hiring day laborers is yet another attraction for employers and homeowners who seek to cut labor costs by avoiding payment of employment taxes, worker benefits, and other costs related to maintaining a regular work force or hiring a contractor.

During the past few years, obtaining temporary work has become easier even for blue-collar, low-skilled workers (Cleeland 1999). The proliferation of temporary agencies and the part-time labor market has made it tremendously accessible to low-skilled workers (Henson1996; Tilly1996). However, obtaining temporary work in the open-air day-labor market is difficult. Day laborers have to contend with cyclical variations related to weather and seasonality, the economic fluctuations in the construction and home-improvement industry, and the daily uncertainty of being selected by a prospective employer. In addition to these factors, day laborers must vigorously compete with each other. At hiring sites, it is not uncommon to see a swarm of men around a car aggressively pointing to themselves or yelling at the prospective employer to hire them. Sometimes, social order at a hiring site breaks down and jostling, arguments, or even fights break out as individuals compete for jobs during bouts of low employment activity. For the most part, however, social order is maintained, and day laborers sustain a modicum of orderliness in their search for temporary work.

Day laborers must also contend with other difficult elements, including complaining merchants and residents and harassment by local law enforcement. In addition, attempting to get hired in public is physically dangerous. Despite the difficulty of procuring temporary employment in this market, it is growing, as indicated in media coverage on this occupation and the number of regulated hiring sites sprouting throughout the United States. Ease of entry for participants, availability of widespread hiring sites, and employers' ease in hiring temporary workers partly drives this growth.

Day-labor work is flexible and open to anyone wishing to work. Women, however, shy away from it, perhaps because they perceive the work to be too labor-intensive and physically difficult and the market to be overwhelmingly dominated by men. An able-bodied man willing to sell his labor in a public setting can do so at any of the many sites in Southern California or elsewhere in the United States. Documents are rarely requested, no participation or "standing" fee is required, and although residents, merchants, and police may harass day laborers, the market is mostly unmolested, with few if any state or local regulations. Regulated sites (official gathering places sponsored by local municipalities, community-based organizations, or private industries) pose some barriers, but even at these sites, access is generally favorable.

For immigrant workers, the day-labor marketplace is an effective device for bringing together prospective patrones (employers). For many participants, day labor may serve as a possible alternative to low-skilled and low-wage employment in the formal economy. For many others, especially those workers with distinct labor market disadvantages, day labor is an alternative to ongoing unemployment and provides an opportunity simply to work. What explains the overwhelming proportion of immigrant workers in day labor—a form of employment fraught with instability, low pay, and difficult, abusive, and sometimes dangerous jobs? Labor disadvantage theory provides a framework for answering this question.

Day Labor and Labor Disadvantage

Labor theory uses the variable of "general disadvantage" to explain the unequal participation in entrepreneurship or self-employment among different groups of workers. The theory asserts that general difficulties in the economy (for example, increasing unemployment levels, downturns in the business cycle) encourage self-employment, independent of the resources of the disadvantaged worker. That is, high unemployment or underemployment would be sufficient to cause someone to seek alternative income-generating activities, self-employment being the alternative of choice. General disadvantage, however, does not affect all workers equally. This has led Ivan Light and Carolyn Rosenstein (1995) to differentiate that variable from "resource disadvantage" and "labor-market disadvantage."

Resource disadvantage occurs when current or historical experience, such as slavery, leads a group to enter the labor market with fewer resources (construed as human capital, which is manifested, for example, as educational attainment, a strong work ethic, good diet, reliable health, contact networks, self-confidence) than other groups. Labor-market disadvantage, in contrast, can arise when groups receive low returns on their human capital for reasons unrelated to their productivity (for example, in the form of discrimination based on racial, gender, age, or birthplace or citizenship characteristics). Resource and labor-market disadvantage can exist together, and, indeed, many immigrants to the United States are likely to suffer both. This results in higher rates of participation in entrepreneurship (Light and Rosenstein 1995), self-employment (Light 1979), and alternative income-generating activities that include informality (Williams and Windebank 1998).

Disadvantage theory argues that self-employment and participation in marginal occupations serves as a mobility ladder. Self-employment may lead to mobility in non-entrepreneurial occupations or to better paying or more secure employment paths. The experience, social capital, and job skills acquired through self-employment are attractive characteristics not lost on employers, and these things can often make the difference in securing a better job. Immigrant workers often take advantage of the experiences gained from on-the-job training and the variety of occupations found in day labor. In securing a job or negotiating wages, they may verbally or more subtly advertise their occupational preference or specialty. Day-labor painters, wearing the painter's standard white attire splotched with paint from previous jobs, will seek work at hiring sites located at paint stores. Construction day laborers will often carry their own tools for the trade in which they specialize (plumbing, drywall, masonry). Those hoping to capitalize on the moving business go to truck-rental centers (such as Ryder or U-Haul), and those seeking landscape work go to nurseries.

In addition, self-employment provides important quality-of-life characteristics that differentiate good jobs from less desirable ones. Autonomy from a supervisor or boss and the flexibility to not "show up" or to work non-standard hours are important traits valued by most workers, especially the temporary or jornalero self-employed who may be searching for another job, innovating, or developing alternative entrepreneurial projects. It is not lost on day laborers that autonomy and flexibility are keys to pursuing greater economic opportunities and achieving mobility.

Disadvantage theory also sheds light on another outcome of self-employment: survival in a poorly paid and unstable general labor market. The only alternative for immigrants with limited job experience, work skills, lack of documents, language, and other human-capital deficiencies is to work in self-employed occupations even though this means limited mobility, instability, and low wages. Self-employment, rather than offering the freedom of autonomy, flexibility, and decent pay, becomes merely subsistence, a survival strategy to make ends meet.

Light and Rosenstein (1995) separate survivalist entrepreneurs into two types: value entrepreneurs and disadvantaged entrepreneurs. Value entrepreneurs choose self-employment rather than low-wage jobs for various reasons having in part to do with, as the label suggests, their values. For example, Bates (1987) argues that many value entrepreneurs are women, who are attracted to the benefits of self-employment, such as the ability to juggle home and work more flexibly than in regular wage employment. Others prefer the entrepreneur's independence, social status, life-style, or self-concept to the characteristics identified with working a low-wage job (Light and Rosenstein 1995). Steven J. Gold (1992:265; see also Ma Mung 1994) documents that some of the attraction of entrepreneurship for Vietnamese is the "ability to provide them with a level of independence, prestige, and flexibility unavailable under other conditions of employment." Thus, value entrepreneurs select self-employment for reasons that include non-monetary considerations.

In contrast, disadvantaged survivalist entrepreneurs primarily undertake self-employment because, as a result of labor-market disadvantage, they earn higher returns on their human capital in self-employment than in waged or salaried employment (Light 1979; Min 1988; Lee 1999) or they have no other employment options. With few resources at their disposal, disadvantaged groups, such as unauthorized immigrants, have limited options and prefer self-employment to regular wage work, including becoming self-employed in informal or contingent work rather than starting small businesses (Light and Rosenstein 1995:153-54).

Two factors explain labor-market disadvantage for immigrants, particularly those coming from Mexico and Central America: low wages and weak ties to good jobs. The low wages of Latino immigrants are generally attributed to seven factors: 1) lower educational attainment and youthfulness, 2) lack of English proficiency, 3) unauthorized status, 4) country-of-origin, 5) recency of arrival, 6) concentration (segregation) in low-wage firms, industries, and occupations, and 7) race (phenotype) and gender discrimination. Research on the determinants of the lower earnings of immigrant Latinos often point to the symptoms of failed educational policy, such as educational progress and quality of schooling, curtailing high school drop-out rates, which are highest among Latinos, and the very low rates of college completion. Discrimination continues to plague this group, and federal laws and constitutional rulings have made lawsuits more difficult to win. And finally, economic restructuring and other structural changes in labor markets are disproportionately affecting Latinos. New immigrants may face a harder environment in their adaptation to labor-market institutions.

A weak tie to good jobs is another important reason for Latino's lower earnings and their primary form of disadvantage. Most research on this topic (DeFreitas 1991; Melendez et al. 1991) has focused on the determinants of employment, unemployment, and labor-force participation. Similar to low wages, employment outcomes for Latinos are mostly explained by immigrant background, recency of arrival, economic growth, educational background, discrimination, and industrial and occupational employment niches. Unauthorized status increases exposure to unstable, dirty or dangerous, and poorly paid jobs. Higher rates of unemployment for Latinos are of special concern because we know that personal characteristics or education do not primarily explain differences in unemployment. Rather, Latinos have a higher probability of experiencing one or more spells of unemployment and, interestingly, a lower duration of unemployment. That is, job turnover is high and rapid with Latinos and immigrants going in and out of low-skilled jobs because Latinos having a lower reservation wage—a greater disposition to accept lower-paying jobs after losing a job. Latinos also have higher proportions of involuntary part-time work (7.1 percent) compared to African Americans (3.6 percent) or whites (3.6 percent). This indicates that Latinos tend to accept less desirable jobs rather than face unemployment (Meléndez 1993).

Labor disadvantage explains the unequal participation of different groups in entrepreneurship and self-employment. The most useful component of this theory for understanding participation of immigrants in day labor is the model's use of survivalist self-employment, which provides a framework for understanding marginal or informal occupations, such as domestic work or day labor. However, contextualizing labor disadvantage for immigrant day laborers within the broader lexicon of disadvantage for Latinos provides added information to explain their participation in day labor and, similarly, their low participation in non-day-labor work. After describing the research on which this article is based, I provide evidence and analytical support to show that disadvantage theory explains the unequal participation of immigrant Latinos in day labor.

Research Description

The Day Labor Study, the primary data source for this article, provides a unique window through which to better understand day laborers, the characteristics of this market, and the unique attributes that bring together workers and employers for this exchange. As a result, it also allows us to assess the merits of disadvantage theory for explaining the participation of immigrants in this labor-market niche.

Any scientific study of day laborers, a highly mobile, highly visible, yet largely unstudied population, requires a creative research approach. To our knowledge, no other survey or comprehensive methodology for understanding the demographic and other characteristics of these workers and this occupation exists. Special complexities in day labor, such as the sporadic involvement of the men and the fluid nature of the hiring sites (new ones appearing, old ones dying out), make a survey of this occupation very difficult. Finally, other factors come into play when attempting to survey mostly Spanish-speaking men who are trying to secure employment in an open, public space. Despite their ubiquity, day laborers are not a population that can easily be approached to take part in a scientific survey.

The DLS is a face-to-face, random survey of 481 day laborers administered at 87 hiring sites throughout Los Angeles and Orange Counties in Southern California during 1999.4 All but 10 interviews were administered in Spanish by a team of UCLA undergraduate and graduate students and former day laborers. The 6 percent refusal rate (randomly selected day laborers unwilling to take part in the survey) was very low, remarkably so given the difficulties of approaching and convincing a population of immigrants, 84 percent of whom were unauthorized, to participate.5

Because workers faced the possibility of missing work for the day, we offered an incentive of $25 for participation in the survey, which took a little more than an hour. Workers viewed this as adequate compensation. In many instances, we were relieved to find during surveying that a significant number of men either interrupted their interviews with us because they had secured work for the day (we usually successfully rescheduled the interview) or they found work after completing the survey.

It is impossible to determine the statistical universe of the population of day laborers or even to estimate accurately how many are in the United States. As a result, we were posed with a methodological problem of how best to sample and to what extent we could control for bias when surveying at each hiring site. To address the issues of unknown universe and sampling bias, we used the maximum-variation method (Snow and Anderson 1993) to identify sites.6 Despite having identified all known hiring sites in the region, a sampling challenge still existed because each site had a relatively fluid population, making it very difficult to select a random sample. Would we be surveying only those men not procuring work (that is, those standing and seeking employment), thus biasing the sample against those workers who had already secured work that day or previous days? What about those day laborers who had found temporary work and would not be included in our sample on the day we surveyed their site? We decided that the best approach would be to select a random sample of respondents from each of the sites we had identified and to survey all identified hiring sites and to do so during specific time frames (for example, between 7:00 a.m. and 10:00 a.m.) when workers were most likely to be seeking employment. This procedure would at least insure a rigorous and consistent sampling procedure across all ofthe hiring sites.

To assess labor disadvantage theory, I present the survey's key demographic, social, and labor-market findings below. The small number of missing responses, as is customary, have been omitted from the tabulated data. In addition, all data are weighted to represent the overall day-labor population in Los Angeles and Orange County.

The Workers

While driving during the early morning through the streets of Los Angeles, or in other immigrant-rich cities, one is likely to encounter a group of scruffy, dark-skinned, Spanish-speaking men who are eagerly courting passersby or hovering around a car and aggressively pointing to themselves in hopes of securing employment for the day. Who are these men, where do they come from, and what characteristics best describe them and their lives as day laborers? More importantly, what can we learn about them that gives us insight into their participation in this unstable, poorly paid, and seemingly desperate occupation?

A demographic portrait of individuals in this workforce reveals three important insights that help explain their participation. First, although this population is heterogeneous in terms of several key demographic characteristics, day laborers are primarily undereducated and have limited English proficiency, which severely hinders them socially and economically. Second, a significant proportion are unauthorized and recently arrived, putting them in a precarious position in a formal labor market with which they have little familiarity. Finally, almost all are male, Latino, and young, important traits that more generally characterize Latino labor-market disadvantage. However, not all day laborers exhibit these characteristics.

More than one-third of the day laborers interviewed had between nine and 12 years of education, the equivalent of junior high (educación secundaria) and high school (educación preparatoria) in Mexico. Thus, a significant number show modest levels of educational attainment. Further analysis of data reveals that educational attainment measured by number of years may not equate to the holding of a diploma. Indeed, most day laborers, even those with many years of education, had no degree, a detriment when seeking formal employment, which widely requires diplomas and training certificates for participation. However, the relatively high proportion of day laborers with more than nine years of education (38.6 percent) belies the assumption that individuals working in the day-labor market are uneducated. Given that educational certification is unimportant in this market, the low percentage who hold diplomas may be the key to explaining the presence of large numbers of men with modest levels of educational attainment working in day labor.

Almost one quarter (23.4 percent) of those surveyed had been in the United States for more than 10 years, with 10 percent having been here longer than 20 years. Even though this labor market is overwhelmingly immigrant a dichotomy clearly exists between recent arrivals (living in the United States for less than one year) and older immigrants (those who have lived in the United States for 11 or more years). Although more than 80 percent ofthe workers interviewed did not have legal documents to work in the United States, the remainder possess the necessary paperwork, fall into the category of asylum seeker, hold temporary work permits, or have some other INS status. Those who are undocumented may be able to secure fraudulent documents or fake work permits (see Table 1).

Demographic characteristics of day laborers are mixed. Clearly, day laborers are homogenous on several dimensions: race and ethnicity, birthplace, legal status, and country of origin. However, diversity exists with regard to the key characteristics most likely to affect labor-market opportunities, such as the average number of years a worker has lived in the United States. While day labor is an immigrant occupational niche with many recent arrivals participating, it is unclear why immigrants who have long resided in the United States would resort to this type of work given their more mature connection to U.S. norms, customs, and institutions. Linear processes of incorporation would dictate that long-term resident immigrants would shun bottom-of-the-barrel occupations like temporary day work.

The survey revealed a wide range in ages for day laborers, which belies the assumption that workers in this niche are primarily young and single. Even though most of these workers are, on average, young and almost half are single, almost 60 percent are between 28-57 years. DLS survey results indicate that while day labor overwhelmingly provides employment opportunities, albeit inconsistently, to single, youthful, and recently arrived immigrants, it also provides respite from unemployment for older men with head-of-household responsibilities. Finally, even though most day laborers do not have U.S.-based certificates or degrees, they do register modest rates of educational attainment, with a few having attained a college-level education. All together, these data suggest that day labor may be an alternative option for a significant number of immigrants who have been in the United States for 11 or more years, who support a family, and who are relatively educated. Why else would such men stand expectantly at a street corner soliciting work on a daily basis?

Faced with few labor market options in the wider economy, immigrants experience bouts of unemployment or underemployment. To survive, many opt for day-labor work, which provides them with a temporary, albeit difficult, buffer during times of unemployment. The characteristics of day laborers point to labor-market disadvantage as an explanation for their participation. However, disadvantage theory does not explain the presence of individuals lacking demographic characteristics that might be classed as "disadvantages." A closer analysis of how day labor is structured provides a context for explaining immigrant-worker participation in this difficult, unstable, and poorly paid occupation.

Day Laboring

Data from the Day Labor Survey reveal four important findings about the social organization of day labor that help answer why immigrant workers regularly seek employment and participate in this market. Immigrants (1) lack the work experience and job skills needed in similar occupations in regular or non-day labor work; (2) encounter structural and human-capital barriers (lack of documents, transportation, and English proficiency); (3) have better connections to this line of work than to higher paying jobs because social networks and friendships channel them to day labor; and (4) are attracted by the opportunity to bargain and earn competitive (albeit irregular) pay and the non-economic benefits, such as autonomy and flexibility, despite other difficulties associated with this line of work. The first three traits provide strong evidence that disadvantage drives participation in day labor. The last category suggests that characteristics of survivalist value entrepreneurs, described by Light and Rosenstein (1995), also drive immigrant participation in day labor because it provides a modest living that is competitive with other forms of low-skilled and poorly paid employment. At the very least, in the absence of day-labor jobs, immigrant workers would seek other forms of alternative income-generating activities or try employment opportunities in the wage economy. Below, I discuss each ofthese four important findings.

Work Experience and Skill Acquisition

Lack of work experience, certification, and skills makes the prospect of employment more difficult for immigrant workers. In the United States, stringent work-certification requirements and immigrants' lack of experience in higher paying, more stable jobs make it difficult for foreign workers educated in their country of origin to find employment. Many immigrants, despite formal schooling and sufficient qualifications, are unable to compete for occupations that require certification, such as teaching or administration. As a result, many recent arrivals and those who have been in the United States for a long period are employed in under-skilled, poorly paid jobs that offer few opportunities for mobility. Day labor provides not only a job but, perhaps more importantly, an opportunity to obtain valuable work experience and skills in construction and other related industries, such as roofing, plumbing, painting, and landscaping.

Clearly, skills take on a different meaning for day laborers. The acquisition of skills, rather than the competition for jobs based on skill, seems to drive many of the participants. Although most respondents mentioned improving their human capital by obtaining work experience in different trades, most day laborers did not see the lack of specific skill as a hindrance preventing their employment as a day laborer. At the same time, day laborers exploiting the markings of a trade (for example, those wearing painter's overalls or brandishing their own tools) were better able to secure skilled jobs than those who exhibited no recognizable "trade" markings.

The structure of day labor may not be the most advantageous for skilled workers for several reasons. First, in most instances, employers of day laborers are not necessarily looking for skilled workers. Instead, they hire day laborers for menial or labor-intensive jobs that require negligible skill. Day laborers that we interviewed were largely employed in light construction, gardening (including digging holes, cutting shrubs, and landscaping), painting, cleaning and maintenance, and loading and unloading moving vans. Most workers interviewed served as assistants to skilled foremen or licensed contractors. When probed about specific duties, day laborers responded that they performed tasks that involved assisting a skilled worker rather than performing the skilled job itself. Another reason the structure of day labor does not favor skilled workers is that, beside obvious markings, it is very difficult to "advertise" or make known your skill level, much less the degree of experience in that skill. It is also very difficult for employers to verify if workers who claim they are skilled are representing themselves accurately.

Low-skilled workers in the United States—immigrant and non-immigrant alike—are often constrained from participating in meaningful and decent paying jobs for reasons other than their human capital. Factors such as race and gender discrimination in hiring, language constraints, and the availability of good jobs requiring few skills prevent low-skilled workers from obtaining gainful employment. Day laborers are not immune to these factors and are confronted with additional immigrant-related and other barriers that prevent their employment in more formal labor markets while confining them to day labor and other forms of flexible and contingent labor. Day labor, while rarely providing stable work, does offer opportunities to gain experience and hone job skills in construction and related industries, which thereby increases the human capital of the participants.

Barriers to Work in the Formal Labor-Market

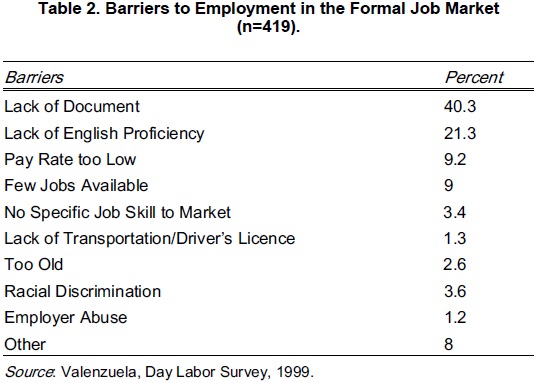

Determining both the types of barriers day workers confronted in attempting to secure formal employment and the factors that confine them to the self-employed niche provides insight into the workers' circumstances and suggests that underemployment and labor-market disadvantage are primary factors (see Table 2).

As might be expected of unauthorized immigrants, lack of documents was the primary factor preventing day laborers from finding other types of employment. Though thousands of unauthorized immigrants obtain employment with fraudulently acquired documents or because of employers' failure to verify authenticity, the possibility of getting caught and deported is a real threat when seeking formal employment.

Several other key labor-market disadvantages were important as well. For example, almost 20% of all those interviewed mentioned low pay and unavailability of jobs as the most important barrier preventing their participation in non-day-labor work. They also reported labor-market and resource (that is, human capital) disadvantages. Lack of skills and unfamiliarity with U.S. work customs or norms along with the inability to speak English also emerged as debilitating barriers. The factors that prevent day laborers from participating in formal labor markets relegate them to day labor. These barriers also help us understand the preponderance of immigrants in this sector.

Social Networks and Friendship

The role of social networks among immigrant workers is important for understanding their participation in day labor. Although social networks are important in other job markets and social settings, they are critical for job acquisition at open-air hiring sites. Social networks are not the only mechanism workers use to secure jobs at hiring sites. As described earlier, jostling and drawing attention to oneself aggressively, waiting expectantly, and participating in job queues at regulated sites are other methods laborers use to secure day-laborjobs.

Social networks are important in immigrant settlement and job incorporation (Mines 1981; Portes and Bach 1985; Massey eta/. 1987; Chavez 1992; Hondagneu-Sotelo 1994b) —a role not lost on recent arrivals. Immigrants create layers of resources and strategies for dealing with a new and larger society. Immigrant networks are based on the individual, the family, and an extended network of relatives, comrades, paisanos (fellow members of the home community), trusted friends, and neighbors. By forming a network in a region, local community, or neighborhood, immigrants increase the number of people they can turn to for help in securing a job or obtaining legal or medical assistance in a crisis, and for short-term lending and borrowing of resources. Most immigrants know someone in their area of destination who can provide shelter, information on where to find a job, and help with other settlement issues. This important factor usually means the difference between an immigrant acquiring a job or not, with the consequence of having to return to their country of origin.

Thus, the role of social networks is perhaps even more important among low-skilled immigrants who have few employment options, especially in the formal labor market. Participation in the day-labor market—where employer contacts are infrequent and periods of unemployment frequent—heightens that dependence on social networks and the culture of reciprocity.

For example, most employers of day laborers hire between one and three workers on any given day. The selection is often done by a "broker" or lead person, someone who stands out perhaps because he had prior experience with the prospective employer, was aggressive or could speak some English, or simply through a stroke of fate. The employer will tell the broker to select, for example, three or four "strong, dependable, and hard working" men, and the broker will pick his friends or acquaintances to join him for that particularjob. During the job, he serves as a liaison through whom the employer communicates work orders and negotiates wages. Thus, a laborer's relationship with other workers, especially those who are most experienced, is advantageous in securing ajob.

Friendship among day laborers is important because it provides companionship, camaraderie, and a source of advice and favors. For example, money is often pooled for a bus ticket to bring a family member or friend to the United States or so a worker can return home for a special event or family emergency. Workers often share housing, and they lend each other money for rent and food during bouts of low employment. The proximity of the workers at the hiring sites facilitates the settlement of these loans and encourages exchange of favors and sharing of sources of information. This communication at hiring sites aids in organizing social and sporting events, where workers and their families can meet for recreation.

The sense of community and mutual respect engendered by these social networks may provide a clue to why laborers return daily to seek informal jobs. Even though the majority of day laborers expressed a desire to secure full-time, steady employment, their participation in the day-labor market, unlike that in the formal labor pool, provides the social contact and networking needed for settlement, subsistence, and opportunity.

Social networks and friendships funnel recent arrivals into various occupational niches, including day labor. Most day laborers are newcomers to the United States, fully a third having been in this country for less than one year. As a result, much of their channeling into this niche is the result of either hearing (through friends or relatives) about this unique occupation or coming into contact with day laborers through social settings or other activities. Social networks also serve very important survival and social functions that give meaning and agency to the everyday lives that men confront in this occupation.

Earnings and Bargaining

The flexibility in negotiating a wage and the range in possible earnings makes this market both extremely risky and attractive to participants. Experienced day laborers often mentioned their ability to negotiate a fair wage for a day's labor. They boast of their experience and deft ability to call an employer's negotiating bluff successfully or walk away from a job. Learning how to negotiate pay for a day's labor is not easy, especially with a seasoned employer or contractor who is unwilling to be flexible. Day laborers were quick to draw on their experiences to provide their comrades with useful tips on negotiating ploys. At one site, the laborers, among themselves, commonly set a minimum wage (for example, $10.00) so that they would not undercut each other when a prospective employer attempted to negotiate a lower rate. (This tactic is not always successful since the employer has the ability to hire elsewhere.)

Only those men who have semi-steady day-labor employment or who are able to obtain higher paying day-labor jobs are able to bargain aggressively for a better wage rate. This option is unavailable to recently arrived immigrants, who know little about this market, or to desperate immigrant workers who have not contracted work in several days or weeks.

It is impossible to calculate accurately a minimum wage for day labor since no federal or state mandated provision exists for informal work. One way to determine a minimum wage was to ask the workers their reservation wage, which is the lowest amount for which a person is willing to perform a particular job or task. The mean hourly reservation wage of the respondents interviewed for this study was $6.91. As a result, on average, laborers in the Day Labor Survey sample refused to work for less than $6.91 per hour, about $2.00 more than the 1999 federal minimum wage. The reservation wage fell to $6.21 per hour during periods of increased unemployment (wintertime, the rainy season) or when men repeatedly had bad luck securing jobs. Because this figure is a mean, many workers had reservation wages lower and higher than this figure.

The average wage a day laborer received for a one-day job (non-hourly) was $60, though it was not unheard of for workers to earn upwards of $80 to $100, depending on the job being contracted. Regardless of pay rate and arrangement, the pay earned each week is highly variable, and the weekly job schedule is constantly in flux due to swings in demand, weather, and supply of workers. Adding to this variability are uneven rates of pay from different employers and the inability ofday laborers to secure employment consistently. Far from stable, day-labor work is difficult to obtain on a consistent basis. The relatively good pay is usually offset by bouts of frequent unemployment and is highly dependent on deftness in negotiating a fair wage.

Earnings of day laborers are mixed. On the one hand, the mean yearly income ($8,489) is slightly above the poverty threshold for a single person in 1999.7 On the other hand, the mean day-labor hourly rate of $6.91 seems promising. That wage is about $1.15 higher than the State of California minimum wage and slightly below the City of Los Angeles's Living Wage Ordinance.8 Calculating the mean reservation wage for day labor, a full-time, year-round worker would earn about $14,400, almost 175 percent above the federal poverty threshold for a single person. However, this calculation incorrectly assumes that day labor is steady. Given the highly unstable nature of this work, the mean yearly income of $8,489 more likely reflects actual earnings (see Table 3). The mean yearly income captures cyclical and seasonal variations in employment and hourly rates below and above the average. We also know that, on average, day laborers find work three (2.95) days out of a typical week. Thus, day labor, when secured and when a good wage is negotiated, can provide a worker with the possibility of earning a modest living. Day labor is certainly comparable to other types of low-skilled, low-paying jobs in the formal market and may actually be preferred over other types of employment for at least three additional reasons.

First, day laborers are usually paid daily and in cash. There are, of course, exceptions to this. But the expectation is that a day laborer is paid at the end of the workday. Employers also usually provide lunch. Collecting pay at the end of the workday is especially beneficial to poor people who often have no financial reserves. Payment in cash circumvents having to open a bank account, a key attraction to many unauthorized immigrants who shy away from such institutions due to lack of proper documents and a general mistrust.

Second, since day labor is effectively tax-free, a dollar in day-labor wages is worth more than a dollar in formal wages. In tax-free terms, the $6.91 casual wage is significantly higher than the federal minimum rate of $5.15, about $2.50 higher if you assume a 15 percent tax rate. Similarly, the estimated mean yearly income for day laborers ($8,489) is worth about $1,300 more when untaxed. For a recently arrived immigrant or someone who has worked for minimum wage for many years, this difference is significant.

Third, most day laborers negotiate their wages. The ability to walk away from a job should not be underestimated, especially if the job pays poorly, is dangerous, or particularly filthy or difficult. Knowledge of the market value of skilled and unskilled jobs provides day laborers with a keen advantage over their employers and non-day laborers. It allows day laborers to undercut the formal market rate at a significant discount, yet allows them to earn a rate significantly higher than similar work in Mexico or Central America. Being able to negotiate a day's labor well is key to successfully exploiting this market, a fact not lost on Latino immigrants who come from countries where bargaining is commonplace.

Clearly, earnings from day labor are, at best, mediocre and, for most, it is poorly paid. However, when compared to other low-paid and unstable jobs, day labor may actually be preferred as a result of the flexibility it affords, the ability to walk away from a job if a fair wage is not negotiated, and the benefits of getting paid in untaxed, cash dollars. Working in day labor pays and provides alternative employment in the wage economy, albeit at the low-wage end of the spectrum.

Conclusion

Every morning throughout Southern California and the United States, tens of thousands of men gather in search of unstable, difficult, and unevenly paid work. Despite legal, health, and other risks, immigrant workers continue to participate in growing numbers. What explains their participation? A close analysis of this market reveals that worker participation is complex and, at the same time, highly rational when we consider the workers' options in the low-skilled, poorly paid, and unstable formal or secondary labor markets.

Labor disadvantage theory provides an adequate framework from which to contextualize the overwhelming participation of Latino immigrants in day labor. This occupational niche provides employment opportunities and an ability to earn an income whether at the subsistence level or slightly above the poverty threshold. Compared to employment and economic opportunities from the country of origin (Mexico or a Central American nation) for most of these workers, day labor provides an improved outcome. Disadvantage theory offers a framework for thinking about how this market funnels immigrant workers into this occupational position. In the absence of day labor, workers would undertake other forms of self-employment or compete in the regular wage economy with similar or worse outcomes.

At least four important characteristics of this market help explain worker participation in day labor: (1) the lack of work experience and job skills funnel immigrants to this occupation while at the same time providing them with the ability to obtain experience and skill acquisition in varied occupations; (2) limited labor-market opportunities for immigrant workers as a result of structural (e.g., lack of documents) and resource (e.g., English language) barriers; (3) social networks and friendships that aid in economic and social settlement, but perhaps most importantly, channel workers to day labor rather than to other types of jobs; and (4) the ability to earn competitive (albeit low) wages and negotiate an acceptable wage for difficult, dirty, or dangerous jobs and the benefits of autonomy and flexibility characteristic of this line of work.

Although most observers may view day laborers as desperate, when considered in light of other employment opportunities for immigrant Latinos, day labor may be a viable alternative. In terms of desirability, it certainly competes with, if not surpasses, employment in textiles, garment, or other jobs where immigrants concentrate. The participation of so many workers, the processes involved in securing work, the ability to obtain valuable skills and work experience, to foster friendships and establish networks, and to earn a relatively decent living tells us that day labor is much more than meets the eye.

Given few alternatives, immigrants with low levels of human and other capital (social, cultural, and financial) confront a difficult and competitive labor market. These immigrants may well opt for survivalist entrepreneurship or self-employment, in which day labor is a clear option. It is an option, perhaps not viable in the sense that one escapes destitution, but an option that affords one a modest living. In Los Angeles and other immigrant-rich cities, we see this frequently in the informal and fringe commodity market where street vendors, day laborers, and domestics are plentiful. At the very least, survivalist entrepreneurs, as in the case of day laborers, produce goods and services that enhance them and their community's wealth. The alternative is unemployment and poverty.

Bibliography

Bates, Timothy. 1974. "Self-Employed Minorities: Traits and Trends." Social Science Quarterly 68:539-51. [ Links ]

Belous, Richard S. 1989. The Contingent Economy: The Growth of the Temporary, Part Time and Subcontracted Workforce. Washington: National Planning Association. [ Links ]

Biernacki, P., and Waldorf D. 1981. "Snowball Sampling: Sampling and Techniques of Chain Referral Sampling." Sociological Methods and Research 10:141-63. [ Links ]

Carnoy, Martin, Manuel Castells, and Chris Benner. 1997. "Labour Markets and Employment Practices in the Age of Flexibility: A Case Study of Silicon Valley." International Labour Review 136(1):27-48. [ Links ]

Castells, Manuel, and Alejandro Portes. 1989. "World Underneath: The Origins, Dynamics, and Effects of the Informal Economy." In Alejandro Portes, Manuel Castells, and Lauren A. Benton, eds., The Informal Economy: Studies in Advanced and Less Developed Countries. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. [ Links ]

Chávez, Leo R. 1992. Shadowed Lives: Undocumented Immigrants in American Society. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers. [ Links ]

Cleeland, Nancy. 1999. "Temps Take On a Full-Time Role in Industry." Los Angeles Times, Part A, May 29.

Defreitas, Gregory. 1991. Inequality in Work: Hispanics In the U.S. Labor Force. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Fernández, Bob. 1999. "Temporary Jobs Mean Steady Business for Day-Labor Firms." San Diego Union-Tribune, Business Section, C-1, June 9.

Gartner, W. B., and S. A. Shane. 1995. "Measuring Entrepreneurship over Time." Journal Business Venturing 10:283-301. [ Links ]

Gearty, Robert. 1999. "On-Street Hiring Is Under Fire: Suffolk's Bill Targets Use of Day Laborers." New York Daily News, June 20.

Gold, Steven J. 1992. Refugee Communities. Newbury Park, Sage. [ Links ]

Hondagneu-Sotelo, Pierrette. 1994a. "Regulating the Unregulated? Domestic Workers' Social Networks." Social Problems 41 (1):50-64. [ Links ]

----------. 1994b. Gendered Transitions: Mexican Experiences of immigration. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

----------. 2001. Domestica: Immigrant Workers Cleaning and Caring in the Shadows of Affluence. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Henson, Kevin D. 1996. Justa Temp. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [ Links ]

Lee, Jennifer. 1999. "Striving for the American Dream: Struggle, Success, and Intergroup Conflict among Korean Immigrant Entrepreneurs." In Min Zhou and James V. Gatewood, eds., Contemporary Asian America. New York: New York University Press. [ Links ]

Licht, Walter. 1983. Working for the Railroad. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Light, Ivan. 1979. "Disadvantaged Minorities in Self-Employment." International Journal of Comparative Sociology. 20:31-45. [ Links ]

----------, and Carolyn Rosenstein. 1995. Race, Ethnicity, and Entrepreneurship in Urban America. Hawthorne: Aldine de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Ma Mung, Emmanuel. 1994. "L'Entreprenariat Ethnique en France." Sociologies du Travail 36:185-209. [ Links ]

Malpica, M. Daniel. 1996. "The Social Organization of Day-Laborers in Los Angeles." In Refugio I. Rochin, ed., Immigration and Ethnic Communities: A Focus on Latinos. East Lansing: Julian Samora Research Institute/Michigan State University. [ Links ]

Massey, Douglas, Rafael Alarcón, Jorge Durnand, and Humberto González. 1987. Return to Aztlan: The Social Process of International Migration from Western Mexico. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

McQuiston, John T. 1999. "Immigrants Help Defeat L.I. Bill Banning Street Job Markets." The New York Times, June 30.

Meléndez, Edwin, Clara Rodriguez, and Janis Barry Figueroa, eds. 1991. Hispanics in the Labor Force. lssues and Policies. New York: Plenum Press. [ Links ]

----------. "Understanding Latino Poverty." Sage Race Relations Abstracts 18 (1):3-42. [ Links ]

Min, Pyong Gap. 1988. Ethnic Business Enterprise: Korean Small Business in Atlanta. New York: Center for Migration Studies. [ Links ]

Mines, Richard. 1981. "Developing a Community Tradition of Migration: A Field Study in Rural Zacatecas, Mexico, and California Settlement Areas." Monograph in U.S. -Mexican Studies 3. La Jolla, Program in U.S. -Mexican Studies: University of California, San Diego. [ Links ]

Mund , Vernon A. 1948. Open Markets, an Essential of Free Enterprise. New York: Harper. [ Links ]

Polivka, Anne. 1996. "Contingent and Alternative Work Arrangements, Defined." Monthly Labor Review, October:3-9.

----------, and Thomas Nardone. 1989. "The Quality of Jobs: On the Definition of Contingent Work." Monthly Labor Review, December 9-14.

Portes, Alejandro, and Robert L. Bach. 1985. Latin Journey: Cuban and Mexican Immigrants in the United States. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

----------, Manuel Castells, and Lauren A. Benton. 1989. The Informal Economy: Studies in Advanced and Less Developed Countries. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. [ Links ]

Quesada, James. 1999. "From Central American Warriors to San Francisco Latino Day Laborers: Suffering and Exhaustion in a Transnational Context." Transforming Anthropology. 8 (1-2):162-85. [ Links ]

Rollins, Judith. 1985. Between Women: Domestics and Their Employers. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [ Links ]

Romero, Mary. 1992. Maid in the U.S.A. New York and London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Sassen-Koob, Saskia. 1985. "Capital Mobility and Labor Migration: Their Expression in Core Cities." In M. Timberlake, ed., Urbanization in the World Economy. Orlando: Academic Press, pp. 231-65. [ Links ]

Schmidt, Fred H. (with research assistance of Patricia McFeely). 1964. After the Bracero: An Inquiry Into the Problems of Farm Labor Recruitment. A report submitted to the Dept. of Employment of the State of California by the Institute of Industrial Relations: University of California, Los Angeles. [ Links ]

Snow, David A., and Leon Anderson. 1993. Down on Their Luck: A Study of Homeless Street People. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Tilly, Chris. 1996. Half a Job: Bad and Good Part-Time Jobs in a Changing Labor Market . Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [ Links ]

Valenzuela Jr., Abel. 1999. Day Laborers in Southern California: Preliminary Findings from the Day Labor Survey. Working Paper 99-04. Center for the Study of Urban Poverty, Institute for Social Science Research: University of California, Los Angeles. [ Links ]

----------. 2001. "Day Laborers as Entrepreneurs?" Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 21 (2):335-52. [ Links ]

Van Meter, K. M. 1990. "Methodological and Design Issues: Techniques for Assessing the Representativeness of Snowball Samples." In E. Y. Lambert, ed., The Collection ana Interpretation of Data from Hidden Populations (National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Monograph 98). Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, pp. 31-43. [ Links ]

Visser, Steve. 1999. "Laborers Gather As Police Make No Effort to Enforce Ban." The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, July 2.

Walter, Nicholas, Philippe Bourgois, H. Margarita Loinaz, and Dean Schillinger. 2002. "Social Context of Work Injury among Undocumented Day Laborers in San Francisco." Journal of General lnternal Medicine 17, 2002: 221-29. [ Links ]

Way, Peter. 1993. Common Labor: Workers and the Digging of North American Canals, 1780-1860. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Watters, J. K., and P. Biernacki. 1989. "Targeted Sampling: Options for the Study of Hidden Populations." Social Problems 36:416-30. [ Links ]

Williams, Colin, and Jan Windebank. 1998. Informal Employment in the Advanced Economies: Implications for Workand Welfare. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

This article is based on research funded by a grant from the Ford Foundation. I thank Jennifer Lee, who read an earlier draft of the article, and the anonymous reviewers, who improved the manuscript.

1 Since its initial use by Audrey Freedman in testimony before the Employment and Housing Subcommittee of the Committee on Government Operations (House of Representatives, Congress of the United States), the term "contingent" has been applied to a wide range of employment practices, including part-time work, temporary-help service employment, employee leasing, self-employment, contracting out, employment in the business-services sector, and home-based work. It is also often used to contrast any non-traditional work arrangement against the norm of a full-time wage or salary job. (See for example Polivka and Nardone 1989; Polivka 1996).

2 Unfortunately, the sample size of this survey was too small to make generalizations regarding the characteristics or work arrangements of the overall U.S. day-labor workforce.

3 The dls is the first random and comprehensive survey of day laborers in the United States. The author is the principal investigator of a major, four-part study to collect data on the work and lives of day laborers, of which the dls is the first component.

4 We undertook hiring-site identification six months prior to survey implementation and initially identified 97 sites, of which 10 had disappeared by the start of interviewing.

5 To convince day laborers to participate in our study, we undertook both standard and unique survey procedures. First, we hired approximately a dozen current and former day laborers to be part of our interviewer team. They, along with the team's undergraduate and graduate students, underwent a rigorous three-day training program, in which they learned basic interview techniques, including how to follow skip patterns, avoid leading a respondent, and administer properly a complex survey with many detailed questions. Their performance was reviewed periodically during the survey period. Second, to convince day laborers that our study was legitimate, worthwhile, and not a ruse by some government agency trying to round them up, we developed a process that we called "reconnaissance" fieldwork. We arrived at a site (unfortunately in a white official "UCLA" van) by 7:00 a.m. Approaching groups of day laborers, the reconnaissance team would pass out flyers in Spanish that explained that we were recruiting respondents for our survey, and that the participant selection procedure was random. We explained verbally the objectives of the study, that we were from UCLA (not the ins), that their participation was purely voluntary, and that, if they were selected and chose to participate, their responses would remain confidential. That is, there could be no way that a completed survey could be traced back to them at some future time.

6 We used three methods to identify hiring sites in Los Angeles and Orange Counties. First, using the snowball "referral" system, we approached day laborers at sites and asked them to identify other sites where they also seek day labor. We then visited the newly identified sites and repeated this line of questioning until new sites were no longer being identified. This procedure is derived from traditional snowball sampling (Biernacki and Waldorf 1981; Waiters and Biernacki 1989; Van Meter 1990) and helped us identify 65 hiring sites. After charting these sites on a wall map of Los Angeles and Orange County, we identified gaps (large geographic areas) where sites, unidentified in our snowball referral system, might logically be expected to exist. We then drove through several of these "gaps" (neighborhoods) in search of day laborers. This procedure allowed us to identify an additional 15 hiring sites. Finally, we identified all Home Base, Home Depot, and other types of hardware/home improvement/construction and paint stores where day laborers might likely gather. We then visited each potential hiring site to verify the presence of day laborers.

7 To determine a monthly and then a yearly income figure, we asked day laborers to recall what they might earn during a "good" month (summer) and during a "bad" month (winter). The mean rate of all the responses to this question was then tabulated for each. We then calculated the mean yearly income by adding wages for four "good" months, four "bad" months, and four "average" months (average of good and bad months) = 12 months or one year.

8 The Los Angeles Living Wage Ordinance (No. 171547) requires that nothing less than a prescribed minimum level of compensation (a "living wage") be paid to employees of service contractors of the City and its financial assistance recipients and to employees of such recipients. As a result, not all workers in Los Angeles qualify for the Living Wage.

Información sobre autor

ABEL VALENZUELA JR. Es profesor asociado de planeación urbana y estudios chicanos y director del Centro para el Estudio de la Pobreza Urbana de la Universidad de California, Los Ángeles. Ha publicado en American Behavioral Scientist, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, New England Journal of Public Policy y Regional Studies. Actualmente tiene un contrato con la Rusell Sage Foundation para publicar su trabajo sobre las características demográficas y el mercado laboral de los jornaleros urbanos. Dirección electrónica: abel@ucla.edu.