Introduction

Localized scleroderma or morphea is a chronic, slowly progressive, autoimmune connective tissue disorder that affects the skin and adjacent tissues1. The etiopathogenesis is not yet fully understood, but multiple factors that increase pro-inflammatory cytokines are most likely involved, leading to increased collagen production and extracellular matrix deposition.

Furthermore, in the first two decades of life, hyperpigmented lesions and skin atrophy following Blaschko lines are distinctive features of linear atrophoderma of Moulin (LAM)2. LAM is a rare condition of unknown etiology and chronic and self-limited course, with no specific treatment to date.

We report the case of a male patient with a diagnosis of linear scleroderma, who subsequently developed atrophic and hyperpigmented lesions following Blaschko lines.

Clinical case

We report the case of an 11-year-old male with no relevant clinical history. At 5 years of age, dermatosis appeared in the extremities of the right hemibody, with hyperpigmented plaque-type lesions and sclerosis. Local rheumatology and dermatology services evaluated the patient and diagnosed clinical linear scleroderma. Subsequently, topical and systemic steroid treatment was given with partial improvement. Then, the patient was referred to the pediatric rheumatology of our unit. Laboratory studies, including rheumatoid factor, complement C3, C4, and antinuclear antibodies, were made, which were negative. Treatment with methotrexate and colchicine was started.

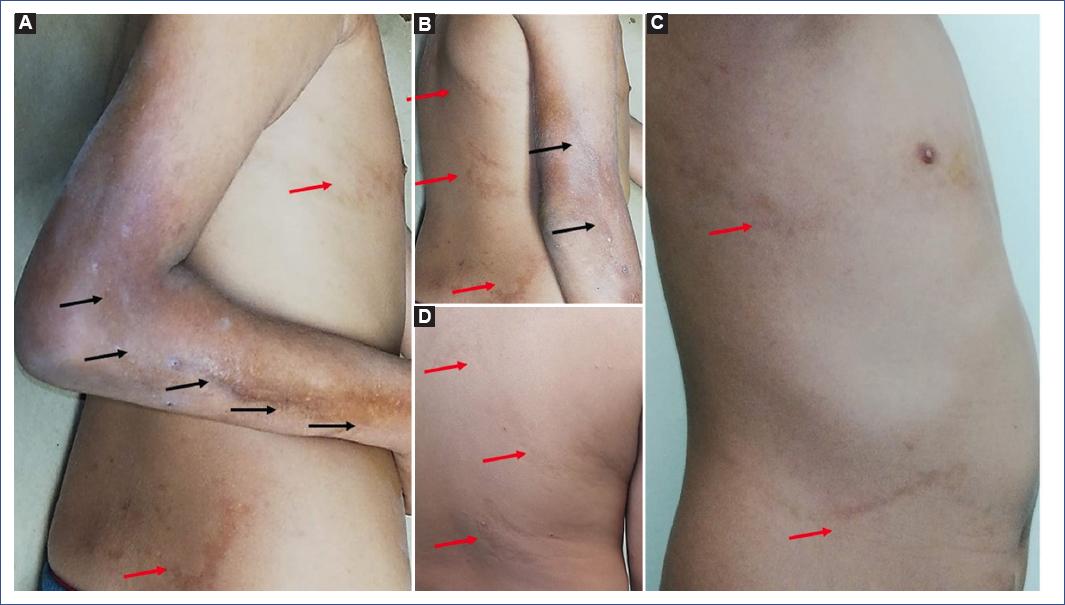

In 2017, the patient was evaluated for the first time in the pediatric dermatology department, clinically confirming the diagnosis of linear scleroderma. Antibodies for Borrelia were requested but reported negative. Due to limited mobility secondary to scleroderma, he was referred to physical medicine and rehabilitation. At 9 years of age, during the clinical follow-up, dermatosis localized to the trunk affecting the posterior and right lateral part of the patient was observed, characterized by discretely atrophic, hyperpigmented linear plaques that followed Blaschko lines, with an absence of induration or evidence of sclerosis (Fig. 1). These lesions were asymptomatic, without inflammation. A biopsy of both dermatoses was taken with the diagnostic proposal of linear atrophoderma of Moulin in a patient with localized scleroderma (Fig. 2). The diagnosis was confirmed. To date, the trunk lesions have remained without progression, clinically without inflammation or sclerosis.

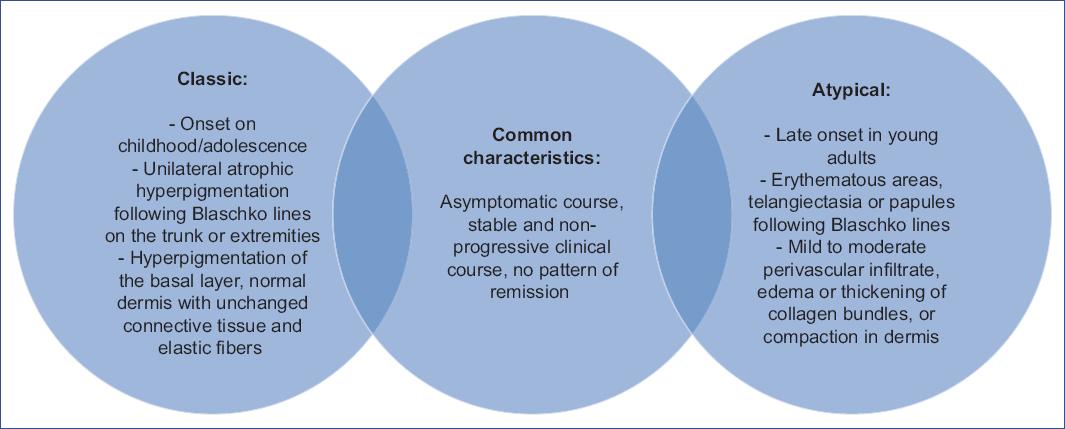

Figure 1 A. Indurated, hyperpigmented plaque with sclerosis and atrophy on right arm and forearm, following a linear trajectory (Black arrows) B. Limitation of full elbow extension is observed. C and D. Hyperpigmented linear plaques, slightly atrophic following Blaschko lines in the posterior and lateral trunk in the right hemibody (red arrows).

Figure 2 A and B. Epidermis with hyperpigmentation of the basal layer; dermis with moderate perivascular inflammatory infiltrate, no alteration in the collagen bundles. C and D. Epidermis with hyperpigmentation of the basal layer dermis with lymphocytic and neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate at the perivascular level, irregular dense collagen foci with atrophy, and scarcity of adjacent tissue. The changes extend to the subcutaneous cellular tissue.

Concerning scleroderma, no more lesions have appeared. Immunosuppressive-based treatment was suspended in December 2019. Finally, the patient continues with rehabilitation therapy, obtaining a functional improvement in the elbow joint and right foot mobility.

Discussion

LAM is a rare disease first described by Moulin in 1992, who published a series of five cases describing hyperpigmented and atrophic lesions3. It is a rare, self-limited dermatological disorder that manifests in childhood and adolescence, with no family history of involvement. The exact etiology is currently unknown, but it is theorized to be a mosaic resulting from a post-zygotic somatic mutational event during early embryogenesis3. This predisposition, together with external factors not yet well established, is responsible for this dermatosis. Clinically, LAM is characterized by a unilateral band-like or linear dermatosis of variable size following the Blaschko lines, hyperpigmented and atrophic4. The lesion does not present induration or sclerosis, it is unilateral, and its usual topography is the trunk and extremities3,5. Its course is asymptomatic with an absence of systemic involvement or progression6. Histopathological findings are controversial. Originally it was described in five cases; only three had a biopsy, where hyperpigmentation was identified without other changes in the epidermis or dermis7. Later reports described hyperpigmentation in the lower epidermis, with perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis, slightly thickened collagen bundles, or compact dermis5. The recommendation is to perform a skin biopsy of both healthy skin and the lesion to establish the histopathological diagnosis since, in some cases, the histopathological findings are very subtle8.

In 2008, López et al.9 conducted a review of reported cases up to that date, proposing the following diagnostic criteria:

Onset from infancy to adolescence

Development of hyperpigmented, slightly atrophic, unilateral lesions following Blaschko lines on the trunk or extremities

Lack of previous inflammation and subsequent absence of scleroderma

Stable and non-progressive clinical course with no pattern of remission

Histologic findings showing hyperpigmentation of the epidermis' basal layer and normal dermis with unaffected connective tissue and elastic fibers

López et al. reviewed 23 cases, of which ten had collagenization of the dermis, and four had no biopsy, meaning that less than 50% of the cases described were those expressing changes at the epidermal level9.

In the literature, we found 46 cases. Only five patients (10.6%) strictly met the criteria proposed in 2008. We identified reports that showed an atypical clinical expression due to the presence of erythematous plaques, telangiectasias, dissemination to trunk and extremities, and histopathological changes in 34 cases (72%). In these cases, findings in the dermis were described, such as thickening and compacted collagen bundles (Table 1)2-4,6-37.

Table 1 Characteristics of linear atrophoderma of Moulin cases reported in the literature

| Patient | Author (year) | Sex | Age of onset (years) | Clinical picture | Topography | Histology | DXC (X/5) and OC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Moulin et al. (1992)7 | M | 8 | Left trunk | Basal hyperpigmentation | 5/5 | |

| 2 | F | 7 | Right trunk | Basal hyperpigmentation | 5/5 | ||

| 3 | M | 15 | Right trunk | Basal hyperpigmentation | 5/5 | ||

| 4 | M | 20 | Left trunk | No biopsy | 4/5 | ||

| 5 | M | 6 | Trunk and left arm | No biopsy | 4/5 | ||

| 6 | Baumann et al. (1994)10 | M | 22 | Trunk and right arm | Epidermis: basal ballonization Dermis: perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, increased collagen |

3/5 | |

| 7 | Larregue et al. (1995)11 | M | 15 | Left trunk | Dermis: collagenization | 4/5 | |

| 8 | Wollenberg et al. (1996)12 | F | 5 | Right trunk and arm | Epidermis: atrophy Dermis: perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and increased collagen |

4/5 | |

| 9 | Artola-Igarza et al. (1996)13 | F | 16 | Left trunk | Epidermis: acanthosis and basal hyperpigmentation

Dermis: perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and increased collagen |

4/5 | |

| 10 | Braun and Saurat (1996)14 | M | 16 | Trunk and left abdomen | Increased collagen fibers | 4/5 | |

| 11 | Cecchi and Giomi (1997)15 | F | 12 | * Classic | Trunk and right arm | Basal hyperpigmentation | 5/5 |

| 12 | Rompel et al. (2000)16 | F | 17 | Trunk and right gluteal region | Epidermis: vacuolar degeneration of the basal area

Dermis: increased collagen |

4/5 | |

| 13 | Browne and Fisher (2000)17 | M | 10 | Classic, also erythematous patches with papules with linear distribution | Trunk and extremities, bilateral | Epidermis: thinned Dermis: prominent vessels and increased collagen |

3/5 |

| 14 | Martin et al. (2002)18 | M | 9 | Left trunk | Increased collagen | 4/5 | |

| 15 | Miteva and Obreshkova (2002)19 | F | 16 | Classic + telangiectasia | Arm, gluteal region, and right leg | Increased collagen | 4/5 |

| 16 | Utikal et al. (2003)20 | M | 23 | Classic + telangiectasia | Trunk and extremities, bilateral | Perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and edema | 2/5 |

| 17 | F | 13 | Erythematous lesions with atrophy and telangiectasia following Blaschko lines | Trunk and extremities, bilateral | Dermis: edema, perivascular infiltrate | 3/5 | |

| 18 | Danarti et al. (2003)21 | F | 14 | Left hemibody | Perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate | 4/5 | |

| 19 | F | 24 | Left arm, trunk, and abdomen | No biopsy | 3/5 | ||

| 20 | F | 38 | Left thigh | Epidermis and dermis without relevant findings | 4/5 | ||

| 21 | Miteva et al. (2005)22 | F | 15 | Gluteal region and left iliac crest | No biopsy | 4/5 | |

| 22 | Atasoy et al. (2006)23 | M | 9 | Trunk and left arm | Increased collagen | 4/5 | |

| 23 | Peching et al. (2005)4 | F | 19 | Classic | Trunk and left thigh | Epidermis: hyperkeratosis, orthokeratosis, basal

hyperpigmentation. Dermis: disorganized collagen with loss of configuration. |

4/5 |

| 24 | Atasoy et al. (2006)23 | M | 16 | Classic + telangiectasia | Arm and right trunk | Epidermis: atrophy Dermis: destruction of collagen fibers, vascular ectasia, perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. |

3/5 |

| 25 | Zampetti et al. (2008)24 | F | 37 | Arm and left trunk | Basal hyperpigmentation, thickening of collagen bundles | 3/5 | |

| 26 | Cecchi et al. (2008)25 | M | 9 | Neck | Basal hyperpigmentation, perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate | 4/5 | |

| 27 | López et al. (2008)9 | M | 16 | Classic | Right arm | Basal hyperpigmentation | 5/5 |

| 28 | Özkaya et al. (2010)26 | F | 18 | Classic + lentiginosis | Bilateral | Epidermis: acanthosis, basal hyperpigmentation, decrease of elastic fibers. | 3/5 |

| 29 | Ripert and Vabres (2010)27 | F | 14 | Left trunk | Basal hyperpigmentation, perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate | 4/5 | |

| 30 | Schepis et al. (2010)28 | M | 14 | Classic | Left trunk | Basal hyperpigmentation, dilated vessels, edema, perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate | 4/5 |

| 31 | Tukenmez Demirci et al. (2011)29 | F | 39 | Left side of the neck | Basal hyperpigmentation, proliferation of vessels, macrophages, and inflammatory infiltrate | 3/5 | |

| 32 | Norisugi et al. (2011)30 | M | 26 | Classic | Trunk and right leg | Basal hyperpigmentation, thickening of collagen bundles, perivascular inflammatory infiltrate | 3/5 |

| 33 | Patsatsi et al. (2013)31 | F | 17 | Classic | Left trunk | Epidermis: thinned, basal hyperpigmentation, increased collagen fibers | 3/5 |

| 34 | Zaouak et al. (2014)2 | F | 11 | Classic | Arm, trunk, and right leg | Basal hyperpigmentation, perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate | 4/5 Treated with methotrexate with clinical improvement |

| 35 | Afshar et al. (2012)32 | M | 20 | Pruritic pink areas that later become hyperpigmented and atrophic while remaining asymptomatic | Trunk and left arm | Epidermal atrophy, Thinned collagen bundles and fragmented elastic fibers |

3/5 Lesions progressed over 46 years |

| 36 | Yücel et al. (2013)33 | F | 23 | Classic + lentiginosis | Right leg | Melanophages and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate | 3/5 |

| 37 | Villani et al. (2013)3 | M | 8 | Classic | Thigh and right gluteal area | Basal hyperpigmentation, perivascular inflammatory infiltrate, thickened collagen bundles | 4/5 |

| 38 | F | 6 | Classic | Abdomen and right leg | No biopsy | 4/5 | |

| 39 | F | 9 | Classic | Left back | No biopsy | 4/5 | |

| 40 | M | 20 | Classic | Left arm | Pigmentation of the basal layer, perivascular inflammatory infiltrate, thickened collagen bundles | 3/5 | |

| 41 | De Golian et al. (2014)34 | M | 10 | Classic | Left side | Normal epidermis Thickening of collagen bundles, Plasma cells, perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate |

4/5 |

| 42 | Zahedi et al. (2015)35 | F | 10 | Classic | Right arm | Basal hyperpigmentation, perivascular inflammation | 4/5 |

| 43 | Yan et al. (2016)36 | M | 15 | Classic | Arm and trunk, ipsilateral | Epidermis: acanthosis, basal hyperpigmentation, perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, and increased collagen | 4/5 Antibodies (+) |

| 44 | Tan and Tay (2016)8 | F | 11 | Classic | Arm, trunk, and right leg | Perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, collagen bundle compaction | 4/5 |

| 45 | Zhang et al. (2020)6 | F | 10 | Classic | Trunk and leg | Basal hyperpigmentation, perivascular inflammatory infiltrate | 4/5 |

| 46 | Present case (2020) | M | 9 | Classic | Trunk | Basal hyperpigmentation, perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate | 5/5 |

*Classic: hyperpigmented, atrophic skin areas following the Blaschko lines.

DXC, diagnostic criteria; F, female; M, male; OC, other characteristics.

In different reports of LAM, we identified a diversity of manifestations that do not fall under the criteria for the disease. For example, Yan et al., in 2016, described a patient with different alterations, including positive antinuclear antibodies, ribonucleoprotein, and anti-SM antibodies36. In 2012, Afshar et al.32 reported that the clinical presentation progressed over 46 years. Other patients were adults3,7,32 presenting with inflammatory-type11,18,34, bilateral17,20,26 lesions associated with lentiginosis26,33, which is atypical for the clinical picture in LAM. From the histopathological point of view, collagen alterations have been identified in a large percentage of cases. This information raises the question of whether the reports were LAM cases or other conditions.

The case described here presented localized linear scleroderma with subsequent appearance of hyperpigmented and atrophic lesions, asymptomatic, with histology supporting the diagnosis of LAM. This coexistence is exceptional, with no other previous report to date.

Regarding treatment, various drugs have been used, ranging from topical steroids, platelet-rich plasma, PUVA therapy [psoralen (P) and long-wavelength ultraviolet radiation (UVA)], oral potassium, and high-dose penicillin, without optimal results1,6. A case treated with methotrexate at a dose of 20 mg per week was reported, where improvement in skin color and texture was clinically demonstrated after 6 months of treatment1. However, further studies are required for its recommendation.

The prognosis of this disease is excellent for life and self-limited. There is no evidence of long-term progression3.

Differential diagnoses of LAM include conditions affecting Blaschko's lines such as linear and whorled nevoid hypermelanosis, incontinentia pigmenti, lichen striatus, epidermal nevi, and atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini (APP)5,6,37. A review of the transcendent conditions to establish the diagnosis of LAM is made.

Scleroderma is a fibrosing dermatosis limited to the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Two subtypes are distinguished: systemic scleroderma with associated visceral involvement and sclerodactyly with Raynaud's phenomenon or localized scleroderma or morphea limited to the skin and underlying tissues38. It occurs predominantly in females and affects children and adults similarly. The peak incidence is between 2 and 14 years of age in children; in adults, between 40 and 50 years of age. Patients with scleroderma usually have a family history of this pathology or other autoimmune disorders39. The etiology is not yet well established, but several elements involved in the fibrosis pathway are recognized. Among these elements are vascular damage or anomalous activation of T lymphocytes with abnormal tissue production by fibroblasts, which could interact with external triggering factors, such as trauma, insect bites, vaccinations, and exposure to X-rays, resulting in the development of sclerosis7,40.

The clinical classification depends on the consulted literature, but it is usually divided into circumscribed morphea with linear expression (including trunk and extremities, en coup de sabre, and Parry-Romberg syndrome), generalized, pansclerotic, and the mixed variant38.

In the early stages of the disease, differentiation of scleroderma and systemic sclerosis is impossible, as both present perivascular lymphocytic infiltration in the reticular dermis and endothelial inflammation. They also share standard features such as thickening of collagen bundles extending into the subcutaneous tissue, loss of eccrine glands, and involvement of blood vessels in later stages38.

When there is head and neck involvement, a periodic ophthalmologic examination is indicated to rule out third cranial nerve damage since it may be irreversible38.

The clinical picture consists of an indurated plaque of insidious onset, with an active border of violaceous or erythematous coloration and a slightly whitish center that progresses to sclerotic tissue41. Later, the plaque becomes pigmented with loss of adjacent tissue. Extracutaneous involvement is exceptional. However, it may be associated with myalgias, arthralgias, fatigue, and central nervous system fibrosis, present in up to 22% of cases38. The evolution is variable and tends to progress, especially in childhood-onset cases, although it usually becomes inactive after 3-5 years42.

Multiple treatment options include phototherapy, topical or systemic steroids, topical calcipotriol, oral calcitriol, tacrolimus, topical pimecrolimus, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, intralesional interferon-gamma, cyclosporine, D-penicillamine, imiquimod, and penicillin. In pediatric patients, the therapies with the highest degree of evidence are phototherapy and pulse regimen with corticosteroids and methotrexate42.

Moreover, APP is a rare dermatosis characterized by mild dermal atrophy affecting adolescent and young adult women43,44. It was first reported in 1923 by Pasini as “progressive idiopathic atrophoderma” and was described later in 193645. It predominates in young women in the second or third decade of life, has a predilection for the trunk, and clinically presents as a plaque, single or multiple, atrophic with well-defined borders, hyperpigmented, non-indurated, which can vary in size and tone, and tends to be bilateral. APP may be accompanied by pruritus, pain, or paresthesias45. About 100 cases of APP have been described in the literature. Although the cause is still unknown and no genetic factors have been identified, Pasini and Pierini reported familial atrophoderma43,45. Some authors have related it to Borrelia infection44.

Regarding histology, the most characteristic finding is a decrease in dermal thickness and collagen changes, including atrophy, sclerosis, fragmentation, and hyalinization. The elastic fibers show reduction and fragmentation. The adjacent tissues do not show alterations32. To date, no definitive treatment is available. However, when positive antibodies for Borrelia are present, it can be managed with tetracyclines, although the response is partial43,45.

The coexistence of different sclerodermiform conditions is recognized. Most reports describe the association of morphea with lichen sclerosus and atrophic lichen42,46-48 and of morphea with APP26. However, in the latter case, several authors share the theory that both conditions are part of the same spectrum or that APP is an abortive variant of morphea37,49.

Currently, the possibility has been raised that LAM, APP, and linear scleroderma are part of the same spectrum, as they all share some clinical and histological manifestations34,49.

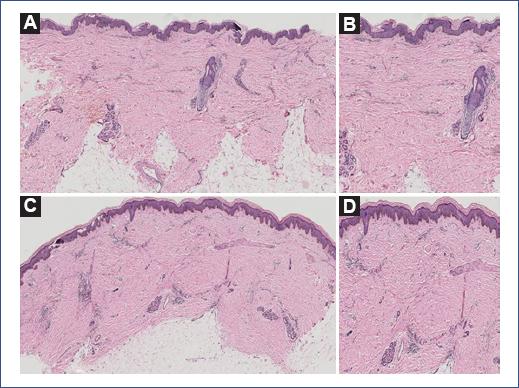

Finally, from the reported cases, we compiled and analyzed the following common features: (a) dermatosis characterized by hyperpigmented patches and mild atrophy following Blaschko lines; (b) children and adolescents; (c) on trunk and extremities, unilateral; d) epidermis with hyperpigmentation, scarce perivascular lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate, dermis unchanged, or the slight thickening of collagen or compaction without alteration of elastic fibers; e) asymptomatic course, without clinical progression to induration or involution. This information represents an opportunity to expand the previously proposed diagnostic criteria for LAM, adding a subdivision according to the findings (Fig. 3).

LAM is a controversial entity. Of the 46 published cases, only five fully meet the diagnostic criteria already established. Furthermore, these criteria are exceeded, as they are not strictly met, mainly due to histopathological findings. In the literature, LAM is a dermatosis without changes in the dermis. However, more than 70% of the reports show alterations in the dermis: collagenization, thickening of bundles, edema, compacting of collagen bundles, or decrease of elastic fibers. Therefore, we face a dermatosis that shows the importance of the clinical-pathology-evolutionary correlation. Overall, the above provides a guideline to reconsider LAM, linear scleroderma, and APP as part of a clinical and histopathological spectrum, concurring in the manifestations of hyperpigmentation, the Blaschko lines pattern, the presence of thickening of the collagen bundles, or the compacting of the dermis, where LAM would be the mildest form, APP an intermediate form, and scleroderma as the significant clinical expression due to tissue damage.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)