Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista electrónica de investigación educativa

versión On-line ISSN 1607-4041

REDIE vol.10 no.1 Ensenada may. 2008

Artículos arbitrados

Video Game Narratives: A "Walk–Through" Of Children's Popular Culture And Formal Education

Narrativas de los videojuegos: un recorrido por la cultura popular infantil y la educación formal

Rut Martínez Borda* y Pilar Lacasa*

Psycho Pedagogical Department University of Alcala. * Aulario Mª de Guzmán c/ San Cirilo s/n 28801 Alcalá de Henares, Spain. E–mails: rut.martinez@uah.es, p.lacasa@uah.es

Recibido: 23 de septiembre de 2007

Aceptado para su publicación: 22 de enero de 2008

Abstract

The general aim of this presentation is to explore how video games, supported by conversations and theatrical performances in the classroom, contribute to the development of narrative thought as present in written compositions. Given that one of the primary ecological influences on children is the mass media, we need to consider how media messages create an environment that can teach people about society's rules, attitudes, values and norms (Bakhtin, 1981; Gee, 2003, 2004; Jenkins, 2004). From a methodological point of view we assumed an ethnographical and action research perspective. An inductive approach to the data was taken, in order to define analytical categories that consider participants' activities in specific contexts. Main results show that children's reconstruction of computer games stories is dependent on specific contexts.

Key words: Video games, narratives, theatre, new literacies.

Resumen

El objetivo de este trabajo es explorar cómo los videojuegos, apoyados por las conversaciones que tienen lugar en el aula y en una representación teatral, contribuyen al desarrollo del pensamiento narrativo tal como aparece expresado en las composiciones de los niños. Teniendo en cuenta la influencia de los medios en el entorno de los niños, y que transmiten actitudes, valores y normas , es necesario examinar estos entornos (Bakhtin, 1981; Gee, 2003, 2004; Jenkins, 2004). Desde una perspectiva metodológica asumimos el enfoque de la etnografía y la investigación acción. Se adopta una aproximación inductiva a los datos de forma que se define un conjunto de categorías analíticas que consideran las actividades de los participantes en contextos específicos. Los principales resultados muestran que la reconstrucción de las hisotiras presentes en los juegos digitales depende de contextos específicos.

Palabras clave: Videojuegos, narrativas, teatro, nuevas alfabetizaciones.

Introduction

Considering that video games have an important place in the popular culture of children and adults, this article aims to explore how video games can be used as educational tools, focusing on the process of teaching and learning narratives (Gee, 2003, 2004). Children develop their imagination and narrative thinking by listening to traditional fairy–tales. They may dream of being a nobleman living in a castle and fighting a dragon to rescue the princess. In some ways, playing video games also enables the child to live fantastic experiences when he or she turns into the hero of a story, that requires the child to solve specific problems that need to be overcome in the course of the game. Video games, in contrast to traditional fairy tales, contain a hidden story that players discover at the same time as they are playing the game (Newman, 2004; Carlquist, 2002). In this context, we explore the narrative structure of video games and how they can be used to generate new forms of literacy in a digital world.

Our approach combines three parallel, interrelated and mutually informing trajectories: ethnographic, textual, and pedagogical. Consistency, coherence and mutual relevance in these parallel inquiries will be assured, as in each instance our work will employ conceptual models drawn from the work of Mikhail Bakhtin (1981, 1990; Bakhtine, 1984). Regarding video games and other configurative performances as semiotic and cultural tools (Gee, 2003, 2004; Mackey, 2002), we explore their role in the growth of oral, performed, and written narratives. A main focus of our project is to understand how narrative conventions are present across media boundaries, even considering teachers' unfamiliar platforms.

Furthermore, we approach video games by considering them in relation to special types of interactive virtual reality and, at the same time, as simulations of basic modes of real life experiences. In this context, narrative flow as present in mass media can be described in terms of the way in which incoming perceptual (story) information relevant to some vital protagonist concerns cues to emotional activation linked to the protagonist's preferences. The basic story experience consists of a continuous series of interactions among perceptions, emotions, cognitions and action (Grodal, 2003). From this perspective we have been working with teachers to create educational settings in which children learn to construct narratives in a discursive multimodal context (Eskelinen, 2003, 2004; Kress, 2003). We assume that meaning and knowledge are built up through various modalities (for example, images, text, symbols, sound, etc.), not merely via words.

The general aim of this presentation is to explore how video games, supported by conversations and theatrical performances in the classroom, turn into educational instruments.

Specific goals of this study are the following:

1. To explore how specific goals of the participants relates particular uses of video games.

2. To examine video games' contribution to the construction of oral and written narratives in the classroom.

I. Theoretical framework

1.1 Background

One of the important problems which society faces today is the possible effect of the mass media on the generation of violent, sexist or xenophobic situations. In this context computer games have been charged with generating these situations. Given that one of the primary ecological influences on children is the mass media, we need to consider how media messages create an environment that can teach people about society's rules, attitudes, values and norms. Institutions transmit their meaning to each new generation through this process. Long ago, Lippman, (1922/1960) highlighted the importance of the media in this socialization process by pointing out that newspapers–the dominant form of mass media in his time–present the public with information about events that they cannot experience in real life. Thus, the media are powerful agents of socialization because they give the public a great deal of information that cannot be confirmed by sources other than themselves.

What might be the role of computer games in that context? As we have already pointed out, these tools can be explored as educational tools for the development of narrative thinking. The recent deep interest in narrative shown by the human sciences sees in it a natural form for human beings to apprehend reality as a lived experience. Both real and imaginary narratives "subjectivise" experience, inviting the reader to reconstruct what might have happened, opening up rather than closing down possibilities.

Computer games represent one of the most significant "cultural emergent forms" that affect children's leisure time between the ages of 8 and 18 (Livingstone, 2002b). We can even predict that their impact in the not very distant future will be as important as television is now. In that sense, games generate a new communication scenario, in which the classic elements of communication are transformed. Players share not only a form of leisure and a technological skill, but also the specific experience of exploring a different symbolic universe, of submerging themselves in a multimedia and virtual world. New spatial and temporal structures are present, contributing to a redefinition of narrative thinking in a way that is much closer to the cinema than to traditional literary genres (Metz, 1968/2002; Stam, 2001).

1.2 Computer games as cultural and educational tools

Considering computer games as cultural tools, in the most classical sense of this term, we can focus on Vygotsky's ideas:

(...) we may say that the child passes through certain stages of cultural development, each of which is characterized by a different attitude to the external world, by a different way of using objects and by different ways of inventing and using specific cultural devices. This is true, whether this be a system elaborated in the process of cultural development, or a device invented during the individual's growth and adaptation (Luria & Vygotsky, 1992/1930, p. 145).

That is, children learn specific uses of cultural tools, mediated by other people who take part in the social life as members assuming plenary rights in their community. In this respect, they will be discovering new uses of these instruments associated with a conscious control of their activities. In that context Vygostsky (1999) also refers to the voluntary structure of higher mental functions. By using symbolic and cultural tools, the anticipation of subsequent moments of the operation in a symbolic form makes possible to include new stimuli in the present operation. The fact of including symbolic tools in human activity transforms the structure of behaviour. Two principal features make up human activity:

The mechanism of implementing an intention at the moment of its appearance, first, is separated from the motor apparatus and, second, contains an impulse to action, the implementation of which is referred to a future field. Neither of these features is present in the action organized by a natural need where the motor system is inseparable from direct perception and all the action is concentrated in a real mental field (Vygotsky, 1999, p. 36).

Following these Vygotskian ideas, and focusing briefly on the current concept of culture, from a socio–cultural perspective, we distinguish three particularly relevant aspects in this work: 1) Culture introduces people to a symbolic universe, in which systems of meanings have a function that is as much evocative as representational (D'Andrade, 1990). 2) It represents a special consensus in a multiplicity of meanings (Shweder & LeVine, 1984), where even cultural concepts can be understood in terms of heteroglosia (Bakhtin, 1981). In that context, for ethnographers, particular forms of the symbolic action where shared meanings reside need to be explored. 3) Particularly relevant approaches to computer games include relationships between culture and normativity, an idea that leads us directly to the process of social relationships (Rogoff, Topping, Baker–Sennett, & Lacasa, 2002). That is, culture is a product of human thought, emotions and practices that express beliefs and values.

Considering the cultural universe of computer games, we will focus on the concept of popular culture interwoven with the mass media. In that context, specific cultural tools, accepted by individuals or groups, contribute to pleasure and amusement. The fact of getting a world of leisure is peculiar to this type of culture. Buckingham & Scanlon (2003) distinguish between popular and official culture, and suggest in this way the need to introduce in the classroom what pupils experience outside school. Along these lines Dyson (1997) explores the construction of new literacies and values in relation to children's comprehension of "media heroes" by using new and old symbolic codes. Also centred on popular culture, and focusing on the role of the ethnographic method as an approach to this topic, Mitchell & Reid–Walsh (2002) consider the child as an informant and indicate the difficulty of entering into his/her world without assuming authority on the part of the adult; it is evident that the popular cultures of children and adults do not coincide.

Other authors have referred to the presence of cultural models in computer games by assuming that they reinforce or question the player's perspective on the world (Cassell & Jenkins, 1998). Such models are understood not to be merely a set of philosophical, ethical or theological ideas related to a certain morality, but also to refer to the conceptions that people use in daily life. These models are related to interests that individuals attribute to their own social group or those of others with which they are in touch. Sometimes these interests are in conflict. Moreover, models cannot be qualified as good or bad. They are merely useful, in that they allow us to practice in an everyday context without a permanent reflection, although it is occasionally necessary to assume them consciously. It is this concept of morality, anchored in common sense that brings us to the educational power of computer games.

The content of computer games does not relate to the type of content that is normally present in academic disciplines, at least not for the activity that is implicit in them. However, children might well learn from video game designers and not only for the active role of the player in this type of games. In that context, learning from computer games once again relates to the concept of semiotic domain by involving at least four main processes (Gee, 2003):

• Learning new approaches to the world, using new kinds of discourses.

• Participating in a social group that shares this domain.

• Obtaining resources that prepare people for new ways of learning and solving problems.

• An active process of critical learning, in which the learner is situated on a meta–level that allows him/her to establish relationships among the parts of a global system.

1.3 The classroom: A polyphonic context

Looking for the possible contributions of Bakhtin's work to the interpretation of the educational context the concept of polyphony turns out to be especially interesting. According (Morson, 1990, p. 230) polyphony is one of the Bakhtin's most intriguing and original concepts, but he "never explicitly defines polyphony". We accept it as a source of ideas to understand how the classroom could be an environment where each of the participants has their own goals which could coexist trying to construct dialogic relationships. As Bakhtin (1999) describes, the monologic conception of truth is built out of two distinct elements, the "separate thought" and the "system of thoughts" (p. 235). In monologic though we encounter separate thoughts, assertions, propositions that can be by themselves be true or untrue. The most important feature of this kind of thought is their content is not materially affected by their source. By contrast, in a dialogical perspective of thought "the ultimate indivisible unit is not the assertion, but rather the integral point of view, the integral position of a personality" (p. 237).

This dialogic approach to the truth is present in the whole Bakhtinian path, and even present in his first works (Bakhtin, 1990). For example, in Author and hero in aesthetic activity the distinction is first of all in terms of visual perception. If two person look at each other, one sees aspects of the other person and of the space we are in that the other person and of the space we are in that the other does not an–this is very important– viceversa: "As we gaze at each other, two different worlds are reflected in the pupils of our eyes" (Introduction, p. XXII).

Further on, it is interesting to note how he established sharp contrasts between the early nineteenth century novel which was monological in its structure, and the Dostoevsky novel characterized by polyphony, in which no single voice within a narrative is the bearer of a definitive truth. The perspective of the omniscient author is silenced; the central characters are given a particular kind of autonomy through what he described as a dialogical penetration of their personalities. What this means, as we consider computer games as multimodal texts, is that any one voice needs to be silenced in specific social and historical circumstances and that any attempts to monologise it through such authoritarian discourses as we find in religious political or moral dogma, are false attempts to finalize it, to resolve its struggle between competing values. Children need an approach to value education that is supported by other members of their communities and that are respectful of multiple voices present in specific contexts.

Bakhtin's work has also inspired our approach to moral education. Bakhtin (1999) insisted on this dimension of narratives, considering their relationships with human values that can be considered in relation to the ethical and aesthetic dimensions of human activity as located within the everyday context of the school. These two dimensions are implicit in the moral responsibility for activities thatIand other co–develop within cultural and historical contexts. In general terms, the analysis of this process has been better carried out by bearing in mind Bakhtin's critiques of the rationalist models of western philosophy, critiques that enable us to interpret the activity that takes place in the school context. Bakhtin's contributions were to the construction of a moral philosophy that goes beyond Kantian ethics based exclusively on a universal reasoning that supports moral universal judgments based on the sense of duty, independent of the context that is being judged. It is a question of recovering, in some way, concrete knowledge as opposed to the free abstraction of context, but without descending into relativism. In order to focus on specific contexts, we have been exploring the construction of a situated identity, in which children work on a web page and assume the role of authors by placing themselves in relation to a text in which they express to others their own opinions about tv violence. The content of the text is particularly significant in present day Spanish society, and giving the children the task of acting as authors of a digital text enables us to define a specific context within which to explore the process of construction of a personal and cultural identity, in which there emerges an ethical and aesthetic dimension of human activity.

1.4 Computer games and new literacies

When people learn to play computer games they acquire a new literacy. In this context Gee (2003) introduces the concept of semiotic domain that deals as "a set of practices that recruits one or more modalities (e.g. oral or written language, images, equations, symbols, sounds, gestures, graphs, artefacts, etc.) to communicate distinctive types of meanings" (p. 18). That is to say, literacy goes beyond the skills associated with reading and writing: a) it enables people to introduce themselves in a world of images in which meaning needs to be constructed, since people live in a multimodal universe that they need to manage by means of multiple codes, and b) literacy also relates to the way in which something is interpreted; in this respect, a reference to the content exists.

In any case, what turns out to be relevant, assuming Gee's (2003) perspective, is that relations between the multimodal texts of computer games with the written texts are established. These two types of texts are related in several ways. For example, computer games may be inseparable from the descriptions that sometimes appear on the Internet, or even in the plastic box enclosing a CD, on which the most basic instructions are explained. All these texts are a common background for the community of players. It is important to remember them as well as the specific and general descriptions of the games (walkthroughs). Many companies that design games even also sell a guide to the game, making it easy for the player to enter the way of life of the adventure. In this context it is necessary to say that when someone has played a video game, something magic seems to happen with the text associated with it. To sum up, in that context, Gee focuses on three specific principles of learning:

1. Intertextuality, which permits the understanding of multiple texts as a set of interrelated universes.

2. Multimodality, whereby knowledge is constructed across multiple codes and

3. Material intelligence, i.e. learning takes place in relation to the objects of the game environment.

A particularly interesting aspect in this context is the role of emotions as related to the presence of multiple voices in social and historical circumstances, and as they are present in very different expression related to cultural spaces and mass media. Perhaps the most important exponent of those relationships in the twentieth century was Bertolt Brecht. Particularly in his early writings, Brecht (Brecht & Willett, 1992; Winston, 1998) saw emotion as the potential enemy of reason in the theatre and he objected to the use of emotions to draw the audience into complete identification with the sufferings of a protagonist. To Brecht, this kind of abandonment led an audience to ignore the specific decisions which motivated theaction, to learn nothing about how human forces produce injustice and about how this can be remedied. Brecht's theories emphasize that emotions can be harnessed in the service of action but that they must challenge, arouse and provoke the audience, not simply move them to pity.

Especially interesting from this perspective is gesture theatre, which has qualities not found in other forms of theatre. For example, it has kept a freshness, a naiveté, and a communicative warmth that one does not find often in other kinds of theatre today. This is because of its marginal situation in relation to official theatre, from which it differs because it is not as yet familiar with hardened structures or the theatrical machine, which allow it to hide its weaknesses behind exterior effects. Because mimes make a greater effort to dialogue with their audience, they are inventive and sensitive to audience reaction (Lust, 2000).

II. Method

2.1 Modes of inquiry and study design

This study is based on a qualitative analytical perspective based on ecological and ethnographic perspectives (Castanheira, Crawford, Dixon, & Green, 2001). A micro–ethnographic analysis of multimodal discourses was also carried out (Gee & Green, 1998). We have presented in detail elsewhere the steps that we follow in the generation of information and data analysis (Lacasa & Reina, 2004; Lacasa, Reina & Alburquerque, 2002; Rogoff et al., 2002). Differences in experimental methodology are considered.

In this project we acted as participant observers, using both classical techniques (field/work diary, photography, compilation of materials produced by participants) and more modern methods (audio and video recordings, digitalization of all the recordings), and computer programs during the process of information processing (Transana 2.05 & Atlas.Ti 5.067). We also emphasized the importance of organizing the collected data according to temporal criteria.

Following the methodology of previous studies, the analyses was carried out in several phases, while special attention is paid to the question of the units of analysis (Rogoff et al., 2002). Taking ethnographic (Erickson & Schultz, 1981) and sociolinguistic approaches (Gee and Green, 1998), we adopted certain methodological principles that should be borne in mind.

First, our units of analysis were not isolated individuals so much as activities organized by cultural principles and taking place in particular social and historical environments in which participants look for specific goals that make sense of their activities and that are interwoven, in turn, with social and cultural processes.

Secondly, in order to analyze patterns of activities we considered the contributions of every participant as being mutually dependent as well as on the context in which they arise. We looked for methods of approximation to these activities that allowed us to understand their meaning, depending on the situations in which they appeared.

2.2 Sources of data

We were working in a multimedia workshop that took place in a Spanish public school; pupils were in their third year of primary education (8–9 years old). We were participants with the teacher and children in a classroom group. In this context, we worked for a total of nine one–hour sessions, in which 11 boys, 10 girls and their teacher participated, as well as the researchers themselves.

The didactical aim was to develop critical and narrative thinking in the children, using video games as educational tools in the classroom, with the goal of presenting a theatrical play. We were looking that the children approach to the narrative dimension of an adventures' game supported by the teacher and the researchers, all together using new technologies in the classroom. Moreover, the fact that in this workshop children were playing a violent video game created educational situations allowing a critical reflection. The aim of the adult people was to situate the children critically before the screens of the game, by mean of consecutive reconstructions of the game and supporting specific processes of meta–reflection.

2.3 Principles of analysis

As mentioned above, our data were analyzed from an ethnographical perspective. We treat as data the diary documentation produced by researchers and children, including written and audiovisual documentation. A narrative and analytical perspective was combined in our approach to the data (Bruner, 2002)

Firstly, adopting a narrative approach, in each session researchers made field notes, produced a summary of each session, obtained a range of written and audiovisual materials produced or materials used by the children, and audio or video–recorded the sessions (for a total of 45 audiotapes and 23 videotapes). Then, a narrative reconstruction of each session was carried out, focusing on the main goals of participants and their use of specific cultural tools in the classroom. We considered video recordings and children's productions as a first source of the data. The use of Atlas Ti allowed us to define successive moments in the classroom, that later were transcribed in order to explore children and adults activities as related to specific goals and supporting several didactic strategies.

Figure 1 represents how AtlasTi supported the video game analysis by delimitating a specific number of quotes in order to reconstruct all the sessions. Some of them were later transcribed using Transana.

Secondly, an inductive approach to the data was taken, in order to define analytical dimensions that consider participants' activities in specific contexts. Figure 2 show how quotes can be explored in relation to specific codes. This analysis was carried out according to the following steps:

• Draw up specific categorical systems. This process begins by defining macro codes that will gradually be split into much more specific ones.

• Apply this system of codes to the totality of video recordings, in order to carry out qualitative and quantitative analyses.

• Investigate children's reconstruction of computer games stories in specific contexts.

III. Results

We present our results focusing on three specific points revealing different dimensions that influence the use of the video games as educational instruments. First, we detain in how its utilization in the classroom is narrowly related to the goals of the participants, in our case the children, the researchers and the adults. Secondly, the way in which they can be used to facilitate the construction of narratives in different situations and, finally, how there critical discussions, in this case orientated to thinking about the violence, were generated from the game related to its content.

3.1 Working in the classroom according to the participants specific goals

We now describe the main individual phases of workshop depending on the goals that the children, the researchers and the teacher revealed in their activities. A first approach to the videotapes shows predominantly goals that gradually come to be shared, but only at particular moments.

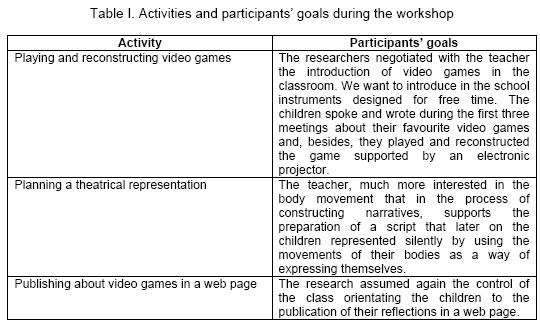

Table I shows three clearly differentiated moments in the course of the workshop, closely related to different forms of activity: the video games, the theatre and the elaboration of a web page. The first and the third moment can be considered to be an expression of predominant goals of the researchers, by contrast, the second one is much more close to the teacher's goal when everybody is engaged on the theatrical representation.

3.2 Exploring narratives in children activities

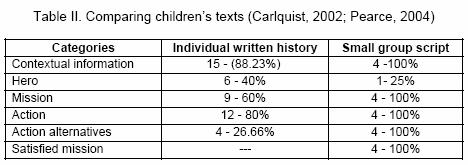

In this presentation we focus on the relationships between the individual text that children wrote, supported by the adults using the video projector and the theatrical script that the children wrote from the reconstruction of the history of the video game, working in small groups. Some differences appeared between the texts that the children wrote in these two situations (see Table II).

Important differences exist between both situations in the way in which the children introduce the different dimension of the narrative texts:

• When they wrote the history individually, after a conversation in the classroom with the teacher, the most frequent categories were those refer to the context of the history and to the actions of the main characters. Bear in mind that, in this case, they were telling what happened in the video game.

• When they wrote the script of the theatre in small group, all the categories were considered except one, the presence of the hero. To interpret this information is not easy. We think that the fact of having turned themselves into the protagonists of the history could be a possible reason. That is, though the references to the hero do not appear in the written text, they were present in the conversations while the children were planning it. Allusions to hero were frequent, for example, in the masks that they use or to the actions that they realize; but this information was not included in the written script.

Pictures and videotapes showed us that all the groups represented the play without oral language; only gestures, corporal movements and physical tools needed to define the characters were allowed. The images presented in Figure 1 give a good idea of what happened in the classroom. Preliminary results show us that in these situations identifications with the main characters were easy. The training of the theatrical script and the scene took place in the fourth session of the workshop, as presented in Figure 2.

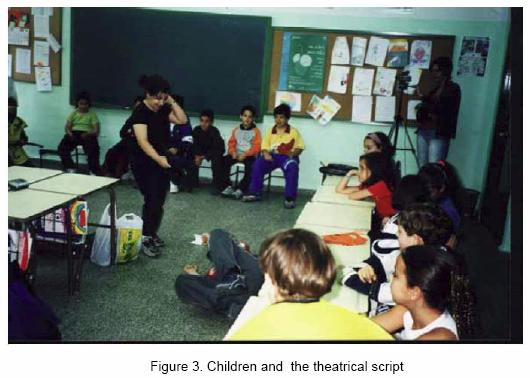

At this point, groups of six pupils adapted the story that they had made up in order to be able to represent it. The children thought how they would interpret it and how they would dress up and finally put it on the stage. Pictures and videotapes showed us that all the groups represented the play without oral language; only gestures, corporal movements and physical tools needed to define the characters were allowed. The image presented in Figure 3 gives a good idea of what happened in the classroom.

3.3 Classroom conversations and moral education

After the representation a critical discussion took place in which adults and children think about their theatrical representations and the violent contents of the video game. Assuming a sociolinguistic approach (Gee, 1999), we explored these conversations. This moment appears as an excellent example in relation to moral education. The teacher and the researchers orient their dialogue by focusing on violent video games. Three important aspects seem to us to be important to highlight as consequence of the conversational analysis:

• Initially the teacher appears very respectful of the children's opinions. But, at the same time she placed them in a difficult situation by raising the following question: "What would you eliminate from this video game?" It was not easy for the children to answer to this question.

• Boys and girls were being able to recognize aesthetic dimensions of the game, but it was difficult to think from an ethical perspective.

• The strategy that the teacher used to overcome this difficulty was to help them in the construction process of a new narrative, avoiding the appearance of elements directly related to the violence. Around this new strategy, reflections were generated by analyzing and identifying the components of specific violent acts, and offering alternatives that would allow new video game screens to be designed.

IV. Conclusions and educational importance of the study

Video games appear to play an important role in the development of narrative thought, when they are used in relation to a symbolic content that allows children to reflect on specific real–life situations.

• Adventure video games possess narrative values that support their effect on the reader. Game has a historical framework, on the basis of which it is the actions of the player that develop the argument.

• The teacher has a very important role to play in transforming a specific tool designed for leisure into an educational resource.

• The process of dramatizing the history enables children to be aware of their own experience with it.

• Video games appear to be an excellent tool to provoke reflection and conversation processes which facilitate moral education, as long as this process is supported by the teacher.

References

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The dialogic imagination. Austin, tx: University of Texas Press. [ Links ]

Bakhtin, M. M. (1990). Art and answerability. Early philosophical essays. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. [ Links ]

Bakhtin, M. M. (1999). Problems of Dostoevsky's poetics (C. Emerson, Trans.). Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Bakhtine, M. (1984). Esthétique de la création verbale (A. Aucuturier, Trans.). Paris: Gallimard. [ Links ]

Brecht, B. & Willett, J. (1992). Brecht on theatre: The development of an aesthetic. Frankfurt and Main: Suhrkamp. (Original work published in 1957). [ Links ]

Buckingham, D., & Scanlon, M. (2003). Education, entertainment and learning in the home. London: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Carlquist, J. (2002). Playing the story. Computer games as a narrative genre. Human IT, 6 (3), 7–53. [ Links ]

Cassell, J., & Jenkins, H. (Eds.). (1998). From Barbie to Mortal Kombat: Gender and computer games. Boston, MA: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Castanheira, M. L., Crawford, T., Dixon, C. N. & Green, J. (2001). Interactional ethnography: An approach to studying the social construction of literacy practices. Linguistics and Education, 11 (4), 353–400. [ Links ]

D'Andrade, R. (1990). Some propositions about the relations between culture and human cognition. In J. W. Stigler, R. A. Shweder & G. Herdt (Eds.), Cultural Psychology. Essays on comparative human development (pp. 65–129). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Dyson, A. H. (1997). Writing superheroes: Contemporary childhood, popular culture, and classroom literacy. New York: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Erickson, F. & Schultz, J. (1981). When is a context? Some issues and methods in the analysis of social competence. In J. L. Green & C. Wallat (Eds.), Ethnography and language (pp. 147–160). Norwood: NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation. [ Links ]

Eskelinen, M. (2003). Video games and configurative performances. In M. J. P. Wolf & B. Perron (Eds.), The video game theory reader (pp. 195–221). New York & London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Eskelinen, M. (2004). From Markku Eskelinen's online response. In N. Wardrip–Fruin & P. Harrigan (Eds.), First person; new media as story, performance, and game (pp. 120–121). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. [ Links ]

Gee, J. P. (2003). What videogames have to teach us about learning and literacy. Houndmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Gee, J. P. (2004). Situated language and learning. A critique of traditional schooling. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Gee, J. P. & Green, J. L. (1998). Discourse analysis, learning and social practice: A methodological study. Review of Research in Education, 23, 119–171. [ Links ]

Gee, J. P. (1999). An introduction to discourse analysis. Theory and method. London & New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Grodal, T. (2003). Stories for eye, ear, and muscles. In M. J. P. Wolf & B. Perron (Eds.), The video game theory reader (pp. 129–155). New York & London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Jenkins, H. (2004). Game design as narrative architecture. Retrieved on November 22, 2006, from: http://web.mit.edu/21fms/www/faculty/henry3/games&narrative.html#1 [ Links ]

Kress, G. (2003). Literacy in the new media age. London & New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Lacasa, P. & Reina, A. (2004). La televisión y el periódico en la escuela primaria: Imágenes, palabras e ideas [Thid Award of Educational Research 2002, Project granted by CIDE–MEC, (BOE, 10–X–1997)]. Madrid: Centro de Investigación y Documentación Educativa–Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia. [ Links ]

Lacasa, P., Reina, A. & Alburquerque, M. (2002). Sharing literacy practices as a bridge between home and school. Linguistics & Education, 13 (1), 39–64. [ Links ]

Lippman, W. (1960). Public opinion. New York: MacMillan. (Original work published in 1922). [ Links ]

Luria, A. R., & Vygotsky, L. S. (1992). Ape, primitive man and child. Essays in the history of behavior. New York & London: Harvester & Wheatsheaf. (Original work published in 1930) [ Links ]

Lust, A. B. (2000). From the Greek mimes to Marcel Marceau and beyond: Mimes, actors, pierrots and clowns: A chronicle of the many visages of mime in the theatre. Lanham, Maryland & London: The Scarecrow Press. [ Links ]

Mackey, M. (2002). Literacies across media. Playing the text. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Metz, C. (2002). Ensayos sobre la significación en el cine. Barcelona: Paidós. Paris: klincksieck. (Original work published in 1968) [ Links ]

Mitchell, C., & Reid–Walsh, J. (2002 ). Researching children popular culture. The cultural spaces of childhood. London & New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Newman, J. (2004). Videogames. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Pearce, C. (2004). Towards a game theory of game. In N. Wardrip–Fruin & P. Harrigan (Eds.), First person: New media as story, performance, and game (pp. 143–153). Cambride: Massachusetts: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Rogoff, B., Topping, K., Baker–Sennett, J. & Lacasa, P. (2002). Roles of individuals, partners, and community institutions in everyday planning to remember. Social Development, 11, 266– 289. [ Links ]

Shweder, R. A., & LeVine, R. A. (Eds.). (1984). Culture theory. Essays on Mind, self and emotion. Cambridge, ma: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Stam, R. (2001). Teorías del cine. Barcelona: Paidós. [ Links ]

Vygotsky, L. S. (1999). The collected works of L.S. Vygotsky. Volume 6. Scientif legacy. Edited by R. W. Rieber New York: Kluwer Academic & Plenum Publishers. [ Links ]

Winston, J. (1998). Drama, narrative and moral education. London: Falmer Press. [ Links ]