Introduction

Pediatric precordial pain is a frequent cause of consultation in the emergency room (ER), it can cause a lot of family stress due to its immediate association with a serious pathology. It represents between 0.3 and 0.6% of all consultations in these services1. This pathology mostly presents itself between the ages of 11 and 14 years2. The causes of precordial pain are very varied and include gastrointestinal, psychological, pulmonary, cardiac, musculoskeletal, and idiopathic etiologies, the last two being the most frequent since they represent between 30% and 40% of the cases. On the other hand, cardiac etiology represents > 5% of the cases1-3.

At present, interest has been placed on the promotion and patient care training for cardiac arrest cases and toward the dissemination of information by the media regarding sudden deaths of some athletes. These cases have generated a rise in the attention given to precordial pain in kids and teenagers, with the intention of discarding a lethal cardiac etiology. However, cases of cardiac pathology or other serious etiologies are extremely rare.

Nonetheless, we have to consider that this type of pain can be incapacitating generating school absences, high hospitalization costs, and multiple studies. In a lot of cases, it ends in a chronic problem, with the duration of < 6 months - in 40% of the cases - and more than a year - in 8% of the patients. This situation proves to be frustrating toward doctors, patients, and families2.

The objective of this study is to determine the incidence and etiology of precordial pain. We also analyzed the semiology and approach of ER service in a private hospital.

Methods

This is a retrospective, observational, descriptive, transversal study that took place from January 2014 to May 2017. Patients oscillated between 0 and 17 years without a clear predominance regarding the sex of the patients. All of them went to the pediatric ER service to get a consult regarding precordial pain.

The Hospital Español de México is a private facility that has a pediatric unit recurred by patients of a medium to high socioeconomic level. They come to be treated of any pathology by ER pediatricians 24 h a day, 365 days a year. If it is needed, the hospital has available consults of any pediatric subspecialty that the patient requires during their stay in ER service.

The hospital has a database that contains every patient that gets admitted to ER, the symptom by which they were admitted, the length of their stay and the diagnosis as they get discharged. We looked for patients that came to ER in the period referred previously that presented precordial pain as their main symptom and took information from de electronic database.

We collected the information presented as results in this study taking into account some of the clinical characteristics described in other studies. Since the same format is used in each of the emergency consultations and the same data are collected from each of the patients, it was not necessary to apply a specific questionnaire to gather the information.

All patients with previous cardiac pathologies and patients with chronic musculoskeletal problems under treatment were excluded from the study.

The local ethics committee approved this study and the authors state that they do not have conflicts of interest.

The variables included in this study were sex, age, the association of precordial pain with syncope, studies performed on the patient, positive family background (the first-degree relatives that experienced sudden death, cardiomyopathy, familial hyperlipidemia, or pulmonary arterial hypertension), and final diagnosis.

The statistical analysis is expressed in total sums and percentages.

Descriptive statistics were performed to obtain the mean, minimum, maximum, and standard deviation of the data. The information gathered was analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Mac. 17.0 program (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

A total of 48 patients with precordial pain were identified in ER service. Of this total, 24 patients are women (50%) and 24 men (50%). The age range was between 2 and 17 years of age. The mean age for women was 12.2 years and the median was 12 years. For men, the mean was 10.9 years and the median was 10 years (Table 1).

Table 1 Precordial pain: sex, age, and positive family background

| Precordial pain (n = 48) | |

|---|---|

| Sex (%) | |

| Masculine | 24 (50) |

| Feminine | 24 (50) |

| Age | |

| Masculine | |

| Standard Deviation 2.2246 | |

| Min: 7 years | |

| Max: 16 years | |

| Feminine | |

| Standard Deviation 3.6475 | |

| Min: 2 years | |

| Max: 17 years | |

| Family background (%) | |

| Positive | n = 4 (8.3) |

| Negative | n = 44 (91.6) |

A total of four cases with a positive family history were found, these four cases had a family history of hypercholesterolemia, and in one case, a non-specified arrhythmia was found, in one other case, apart from the family background of hypercholesterolemia, the father also presented a family history of mitral insufficiency.

In terms of pain semiology, the type of pain was evaluated. In most cases, 62.5%, it was referred to as non-specific, oppressive in 18.7% of patients, pungent in 10.4%, and stabbing in 8.3% of patients (Table 2).

Table 2 Symptoms associated to precordial pain

| Symptomatology | n = 48 (%) |

|---|---|

| Type of pain | |

| Non-specific | n = 30 (62.5) |

| Oppressive | n = 9 (18.7) |

| Stinging | n = 5 (10.4) |

| Stabbing | n = 4 (8.3) |

| Associated symptoms | |

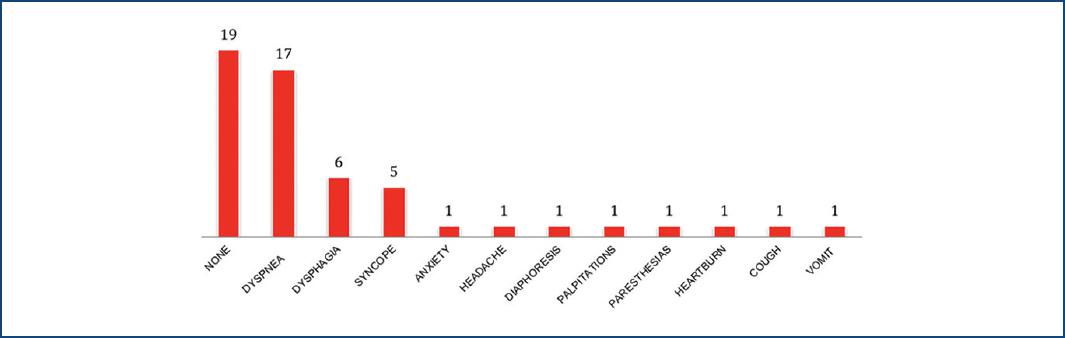

| None | n = 19 (39.5) |

| Dyspnea | n = 17 (35.4) |

| Dysphagia | n = 6 (12.5) |

| Syncope | n = 5 (10.4) |

| Anxiety | n = 1 (2) |

| Headache | n = 1 (2) |

| Diaphoresis | n = 1 (2) |

| Palpitations | n = 1 (2) |

| Paresthesia | n = 1 (2) |

| Heartburn | n = 1 (2) |

| Cough | n = 1 (2) |

| Vomit | n = 1 (2) |

| Duration | |

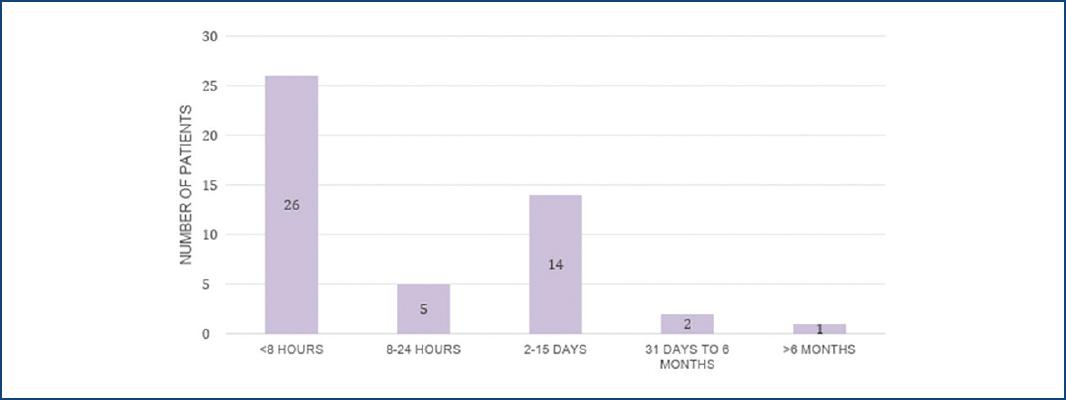

| < 8 h | n = 26 (54.1) |

| 2-24 h | n = 5 (10.4) |

| 2-15 days | n = 14 (29.1) |

| 31 days-6 months | n = 2 (4.1) |

| > 6 months | n = 1 (2) |

| Irradiation | |

| Without irradiation | n = 28 (58.3) |

| Retrosternal | n = 8 (16.6) |

| Left arm | n = 1 (2) |

| Left hypochondrium | n = 3 (6.2) |

| Left hemithorax | n = 2 (4.1) |

| Neck | n = 1 (2) |

| Superior limbs | n = 1 (2) |

| Right arm | n = 1 (2) |

| Right hypochondrium | n = 1 (2) |

| Right hemithorax | n = 2 (4.1) |

We looked for associated symptoms when patients arrived at ER, where the majority regarding 39.5% reported having no other associated symptoms. On the other hand, 17 patients referred dyspnea, six patients dysphagia, five patients syncope, and unique cases were associated with anxiety, headache, diaphoresis, palpitations, paresthesia, heartburn, cough, and vomiting, this symptomatology coexisted in some of the cases (Fig. 1).

The duration of the pain was classified in hours, days, and months. It is important to notice that most of the patients (54.1%) presented acute pain with an evolution of < 8 h, and in only 1 case (2%), it was referred longer than 6 months (Fig. 2).

The majority of the patients (n = 28) communicated that the pain did not irradiate. The most common irradiation, which represented the 16.6%, presented retrosternal pain followed by the left hypochondrium and left hemithorax (Table 3).

Table 3 Irradiation of precordial pain

| Irradiation spot | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Without irradiation | 28 |

| Retroesternal | 8 |

| Left arm | 1 |

| Left hypochondrium | 3 |

| Left hemithorax | 2 |

| Neck | 1 |

| Superior limbs | 1 |

| Right arm | 1 |

| Right hypochondrium | 1 |

| Right hemithorax | 2 |

| Total | 48 patients |

In 30 of the 48 patients, an electrocardiogram was performed, of those 30 only 8 received abnormal results. All these studies were reviewed by a pediatric cardiologist who diagnosed five right branch blockings, one first-degree atrioventricular blocking with the left branch blocking, one sinus arrhythmia, and one sinus bradycardia. A total of three echocardiograms were performed in ER service, two were normal, and one presented pulmonary pressure of 40 mmHg.

Of 48 patients, 32 had a thorax X-ray performed and only one threw an abnormal result of an increase in alveolar bronchial tissue. In one patient, blood biomarkers as troponin I and creatine phosphokinase with isoenzymes were taken, the results of these tests were negative.

After the evaluation of the samples and the analysis of the precordial pain and its characteristics, the final diagnoses were registered and only five patients were admitted to hospitalization with posterior discharged without any complications. Only in 2% of our cases, a cardiac etiology was found: pulmonary arterial hypertension. The musculoskeletal causes such as costochondritis were the most frequent with a slightly higher percentage in men than in women, followed by gastroesophageal reflux in which an equal percentage of 14.5% was found in both sexes (Table 4).

Table 4 Cardiac and non-cardiac etiologies

| Masculine n = 24 (50%) | Feminine n = 24 (50%) | Total percentage (100%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac causes | |||

| Pulmonary arterial hypertension | n = 0 (0) | n = 1 (2) | (2) |

| Non-cardiac causes | |||

| Musculoskeletal | n = 10 (20.8) | n = 9 (18.7) | (39.5) |

| Costochondritis | n = 1 (2) | n = 0 (0) | (2) |

| Chest trauma | |||

| Respiratory | |||

| Respiratory distress | n = 0 (0) | n = 0 (0) | (0) |

| Intestinal | |||

| Gastroesophageal reflux | n = 7 (14.5) | n = 7 (14.5) | (29) |

| Psychological | |||

| Anxiety crisis | n = 2 (4.1) | n = 5 (10.4) | (14.5) |

| Idiopathic | n = 4 (8.3) | n = 2 (4.1) | (12.4) |

Discussion

In this study, the etiologies of precordial pain are described for the 1st time in a Mexican pediatric emergency department, with the revision of previous works on the subject up to date4. Our results are very similar to those published in other articles, some with big study groups, in which cardiac etiologies represented < 3%5-9.

Some factors we considered include hereditary family backgrounds of importance, duration, and the semiology of the precordial pain. They showed that most of the cases consulted in < 8 h of pain (54%), a piece of information that could be related with the anxiety that the condition causes on patients. These results are opposite to the ones presented by Sert in his 380-patient study in which 32.9% of the cases presented chronic pain of > 6 months versus 10.3% that presented pain < 2 days10.

It is important to notice that a great percentage of the patients referred pain as non-specific and that 35% was associated with dyspnea without determining a respiratory cause in any of those cases. All the patients that presented dysphagia as an associated symptom were diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux disease.

We can highlight that the patient that presented precordial pain related with a cardiac etiology had positive hypercholesterolemia family history. Of the cases associated with syncope, one had cardiac etiology while the others were idiopathic and some were related to anxiety crises. In 2011 Friedman of the Boston Children’s Hospital reported their experience handling 406 patients with precordial pain, 37% presented pain during exercise, 16% associated with palpitations, 1% with positive family background, and in the end, only 5 cases (1.2%) presented a cardiac etiology11.

Of all the laboratory and cabinet studies taken in the emergency department, there was only an alteration in one echocardiogram in which pulmonary hypertension was found and in eight electrocardiograms, which had incidental findings without having a direct association with the clinical picture. Approach plans have been proposed to avoid spending on resources and cabinet studies that may involve the management of precordial pain in children. One of them, reported by Friedman, showed that by adhering to their way of approaching this issue they could avoid 100% of stress tests, 20% of Holters, and 18% of echocardiograms11. Brown, in 2012, reported the evaluation of 212 patients with precordial pain that had taken levels of troponin I, which resulted in 37 positive cases and of these, 18 had diagnoses of myocarditis and pericarditis, determining that this biomarker can be helpful to perform these types of diagnoses when the clinic warrants it12.

Our study reports a 2% incidence of cardiac etiology, with only one case of pulmonary arterial hypertension. The main etiology was musculoskeletal problems, followed by intestinal problems and anxiety crises in the third place. Taking the fourth place was the idiopathic pain that has been reported in other studies as the second most frequent etiology, representing only 12.5% in our series. These results agree with the majority of the published studies, which establish musculoskeletal causes as the main problem. The presence of idiopathic pain as the first etiology may be due in large part to the fact that the pediatric population has difficulty in referring the location and characteristics of pain.

A complete clinic chart is the first and most important step to approach precordial pain because it guides the doctor to rule out cardiac causes and discover the origin of the pain. As the Thull-Freedman article mentions, it is important to question relatives in targeted ways as children cannot always localize and explain the intensity of the pain. It has been observed that, due to this, the pattern and causes that reproduce or intensify the pain are more important to an earlier diagnosis, then the characteristics of the pain13.

During physical examination, up to 49% of the patients that have precordial pain present anomalies and it is important to look intentionally for a musculoskeletal etiology in which up to half of the patients showed costochondral pain orienting to this etiology14-15. From their 1st min in ER, we can assess their vital signs and general appearance to achieve an early diagnosis and detect if the pain has a cardiac origin that could put their life at risk. Physical signs that can lead are to think about a cardiac etiology include centrally located pain that may radiate to the left arm described as crushing pain, chest pain on exertion, and associated presyncope, syncope, or palpations16.

As mentioned by Samuel A Collins et al., the first steps to follow for the approach of a precordial pain diagnosis are the full vital signs, the general, and chest appearance. This happens to try and identify any abnormality or trauma data. After that, the aim is to find palpation of the thorax followed by listening to breath sounds and the precordium looking for heart sounds, murmurs, or some thrill16.

It is important to mention that the study by Drossner et al. identified a population of 4288 patients, whose chest pain was due to cardiac causes, finding 24 of them with pathologies such as dysrhythmias, pericardial disease, myocarditis, acute myocardial infarction, and pulmonary embolism17. Even though these causes are unlikely due to the previously established, we should never downplay the approach and early diagnosis of the etiology of precordial pain in pediatrics.

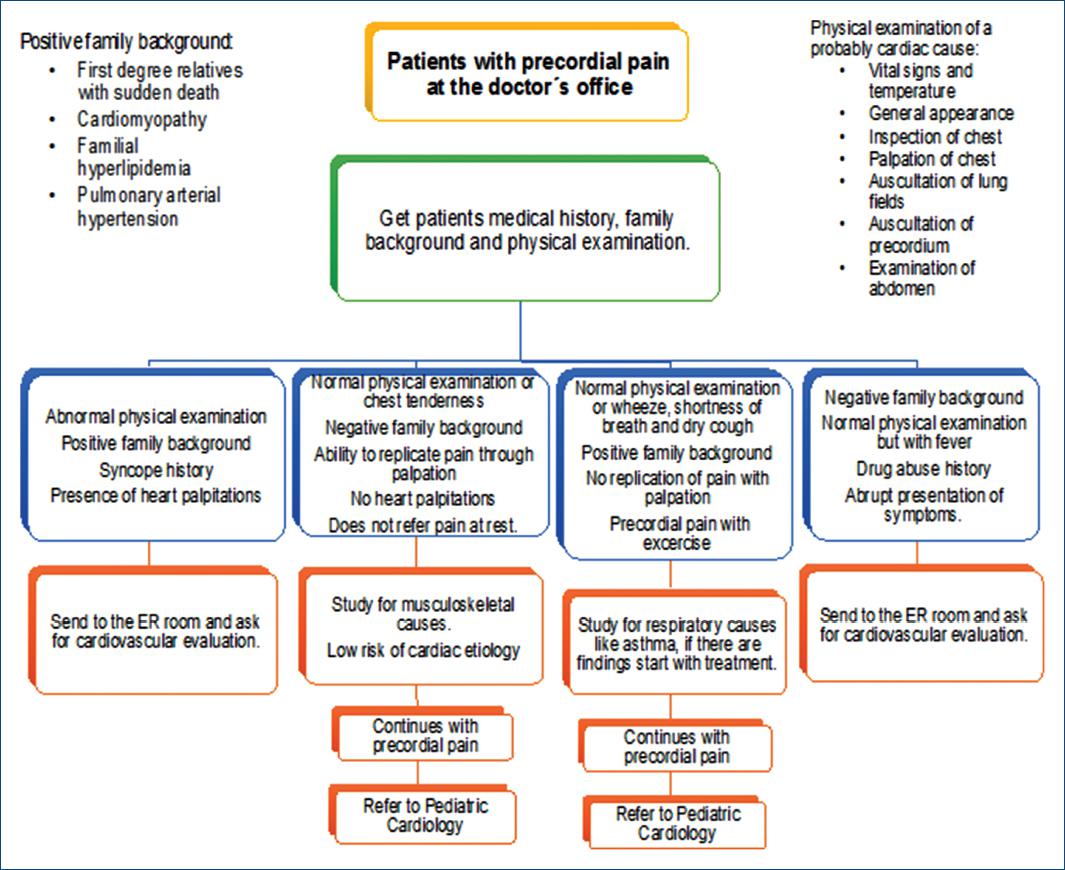

Analyzing our results, we decided to propose an algorithm based on the variables which have a direct impact as well as the main etiologies and associated symptoms that could lead to a prompt diagnosis of a cardiac etiology in precordial pain.

Conclusions

This is the first retrospective study conducted in a private hospital unit where the semiology was analyzed, the etiology was determined, and the precordial pain management was approached in a range of 3 years. Since precordial pain is an alarming pathology for parents, it is important to know the cardiac and non-cardiac causes that could provoke it, as well as to observe that the pathologies that endanger life are the lowest percentage of all cases within this clinical picture.

The importance of knowing more about precordial pain in children lays not only in the fact that there are patients who have an evolution of pain for > 6 months but also that it sometimes become a disabling condition that limits daily activities and with this the quality of life for children.

After the analysis, we were able to determine that the semiology of pain referred by pediatric and adolescent patients, is usually very non-specific, but we also concluded that the clinic is the cornerstone to determine a diagnosis. There is an overuse of cabinet studies which did not allow to establish the final etiology, so it would be important to establish an approach to precordial pain in the areas of pediatric emergency care, based on the guidelines already established in other hospitals, or to establish an individualized plan for our population (Fig. 3).

Ethical disclosures

Protection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of data. The authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)