Introduction

The concept of informality in the labour market is usually difficult to outline. The difficulty comes from the fact that informality accounts for activities that are outside the official records, even sometimes considered illegal. To make things more complicated, there is no a complete theoretical framework to support such a definition. Many agree that informality is a social phenomenon that is real and complex, though not easy to track.

In 1972 the International Labour Organization (ILO) conducted a study on the labour market in Kenya, acknowledging for the first time a distinctive dual economy that operates alongside the modern free-market sector. It was distinctive from the black and illegal market since many activities were not illegal in the sense that they do not harm the economy. Since then, the so called informal sector began to draw attention from scholars and at present we cannot disregard the importance of informal activities in the labour market in developing economies.

In 1993 the ILO introduced a definition of informal sector that eventually got its way into most official statistics around the world. But at the same time scholars began to understand different types of occupations that did not completely fit the definition of employment in the informal sector. As the participation in each labour market is different, the concept of informal employment was left to the particular situations in every country.

Gong and Van Soest (2002) gives an overview of the two views about the rationale of informal work. The first view is that informal jobs are low-productive and secondary. Informal employment then is somehow involuntary because the market for formal jobs is rationed. Then informal work became a buffer between formal employment and unemployment. If this is true, we might expect that informal work will be made up from low productivity workers, young and female workers with low human capital. Another view is that workers choose optimally to be informal or formal, then individuals will voluntarily decide on which job matches better depending in their marginal productivities. In their economic behaviour, informal workers are not different from any other worker. This means that labour market will clear and unemployment will be temporal and voluntary because workers are just waiting to match properly to their desired jobs.

Still, a complete theory has not yet been constructed in order to comprehend the nature of this hidden part of the economy. The existence of informal work is accepted in the academic community, and more or less workable definitions have been constructed. The Mexican National Institute of Statistics, Geography and Information (INEGI) defines employment in informal sector for those individuals working within an informal sector enterprise, which is an economic unit that runs business with resources from the household but without legally becoming a firm, so that its activities and accounting cannot be differentiated from the activities of the household itself. This definition is still useful and allowed to construct national statistics in order to visualize the size of the problem. However, one critique was that the definition of informality based on informal sector enterprise underestimated the size of the problem. The argument was that many workers in precarious, irregular, non-standard or independent jobs were not accounted for.

In 2013 the Mexican National Survey of Employment and Occupations (ENOE) was adjusted to include new changes in the methodology and the inclusion of a new concept of informal employment, which was intended to improve measurements of the informal economy. The whole microdata from 2005 onwards was adjusted to include new series to match the new methodology. The new concept of informal work includes, additional to those that work in the informal sector, salaried workers without social security, precariously self-employed, not-paid workers, those in household services jobs, among others. This definition broadens the scope of informal work but raises some new questions: Does the probability to become an informal worker is radically different? Do both concepts have different cyclical behaviour? We intend at least to give some answers to these questions through this paper.

With this in mind, we decided to re-estimate the gross flows of workers in four categories: Formal employment, informal employment, unemployment and out-of-the-labour force (inactivity) as in Gallardo Del Angel (2013). The flows contain information disaggregated by gender and age. Gross flows of workers are aggregate movements from work categories in two points in time. The gross flows and transitions show how often people change labour status over time and this information has important macroeconomic (and also microeconomic) implications. Furthermore, any cyclical analysis on the gross flows provides important information for policy makers in charge of macroeconomic policy and stability. Understanding the dynamic behaviour of these gross flows helps us to anticipate possible outcomes when specific stabilization policies are carried out. It can be used for the deisgn of anti-cyclical policies at macro-level but also to understand workers’ labour market choices.

This paper contains an analysis on the gross flows of workers from Mexico using the microdata from the ENOE from 2005 to the last quarter of 2012. We follow the same methodology as in Gallardo Del Angel (2013) for estimating gross flows but this time we include the new concept of informal work along with the old definition of informal sector. This paper also follows a similar methodology developed by Blanchard et al. (1990) and Jones (1993). There are two scientific objectives: The first one is to re-estimate the gross flows and transitions of workers in the Mexican labour market using unadjusted data for the new concept of informal work and the old concept of informal sector; and the second, to test empirically possible cyclical properties of these flows along the business cycle for both definitions of informal work.

In the literature there are some interesting works on gross flows of workers for us and Canada. Blanchard et al. (1990) analyses gross labour flows for us using adjusted data. They use the Current Population Survey (CPS) dataset from 1968 to 1986 and disaggregate data by age and sex. They also include a simple model to analyse the cyclical behaviour of workers. Jones (1993) includes an analysis of gross flows of labour for Canada using the Labour Force Survey with monthly data from 1976 to 1991. He uses unadjusted data in order to analyse the cyclical properties of the flows. Jones and W. Craig Riddell (1998) similarly analyse gross flows using comparable unadjusted data for US and Canada.

Bosch et al. (2007) is one of the few works on gross flows of workers in Mexico which accounts for the presence of informality. This paper provides information on gross flows and transitions only for workers in major urban areas and large cities, using the longitudinal data from the Mexican National Survey of Urban Employment (ENEU) from 1987 to 2002. The ENEU is a predecessor of the ENOE and its main disadvantage is that only surveyed urban population then the data used was only representative for urban workers in some large cities.

Another work that includes some information on gross flows is Levy (2008). This paper is a comprehensive work on workers conditions in the labour market with the presence of informality. It contains an study of worker mobility in Mexico, using individual data from the Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS). The main disadvantage is that IMSS data is mainly available for workers in formal jobs, although an effort to estimate gross flows was made using only some sets of micro data from the ENOE.

Gallardo Del Angel (2013) estimates unadjusted gross flows of workers in Mexico, in the presence of informality. This paper uses the whole available ENOE microdata from 2005 to the first quarter of 2012. It uses twelve gross flows so that to include workers in the informal sector.

Similar to Gallardo Del Angel (2013), this paper uses twelve flows instead of the traditional six flows analysis found in Blanchard et al. (1990), Jones (1993) and Jones and W. Craig Riddell (1998). The labour categories used are: Not-in-the-labour force (N), formal employment (EF), informal employment (EI) and unemployment (U). The gross flows represent the movement of workers among these labour categories aggregated for all workers, but also disaggregated by groups of age and gender in order to account for heterogeneity. Gross flows are shown as permutations among the four labour categories, then the flow EFU is the gross flows from Formal Employment to Unemployment, and the NEI is the workers’ ow from Not-in-the-labour-force to Informal Employment, and so on. We add the capital letter P to each flow make to denote the transition probability. In this way the PEIU is the transition probability that a worker becomes unemployed given that previously was Informally Employed, and PUEF is the transition probability that a worker becomes Formally Employed given that previously was Unemployed, and so forth.

We must recall that the first definition of informal sector has being traditionally used to measure the size of informality in the economy, and the new definition of informal employment was included until recently in the Mexican employment statistics, increasing considerably the size of workers in informal activities. We used the ENOE unadjusted quarterly micro data from the first quarter of 2005 to the last quarter of 2012 and compared the results of the aggregate mean flows and transitions. A cyclical analysis is also included in order to show the dynamic behaviour of gross flows along a full Juglar-type business cycle. Mexican economy experienced a business cycle during the period of 2005 to 2012. During the first half of 2009 the Mexican economy touched the bottom of the economic recession affected by the us financial crisis of 2008.

The organization of this work is as follows the first section is a brief introduction, the second compares the two concepts of informal work in Mexico, the third contains an analysis of the gross flows for a quarterly dataset from 2005 to 2012; the forth is an analysis of the cyclical properties of the gross flows. The last section contains the conclusions and final comments.

I. The size of informality

There are two official concepts that capture the idea of informality in Mexico, one that involves workers employed in the informal sector and recently a wider definition of informal workers. The new definition was aimed to include salaried workers in agriculture and household services, as well as many other unpaid, independent or marginal jobs.

In absolute numbers, the new concept of informal work is unexpectedly larger. Using the microdata from the ENOE from the period 2005 to 2012, there was a mean employment of 46 million, with 2.15 million of unemployed workers and 38 million out of the labour force. In average almost 27 percent of the total employment were working in the informal sector (12.36 millions). Using the new concept of informal work the size of informality in the labour market raises up to 60 percent of total employment (27.46 millions). As shown in Table 1, the size informality increased substantially for all groups in the analysis: young workers, veteran workers, male and female workers, but with important differences. Under the new category of informal work, the number of female workers considered informal more than triple while the number of informal young workers more than double. The increase of informal veteran and male workers is less than double.

Table 1: Mexico employment statistics.

| Condition | Total | Old | Young | Female | Male |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment | 46,074,449 | 30,729,877 | 15,344,572 | 17,236,703 | 28,837,747 |

| Unemployment | 2,149,552 | 937,759 | 1,211,794 | 826,780 | 1,322,773 |

| Not-in-the-Labour Force | 38,092,578 | 18,454,162 | 19,638,416 | 27,343,687 | 10,748,891 |

| Informal Sector Definition | |||||

| Formal Employment | 33,707,493 | 22,687,892 | 11,019,601 | 13,862,935 | 19,844,558 |

| Informal Employment | 12,366,956 | 8,041,985 | 4,324,971 | 3,373,767 | 8,993,188 |

| Informal Work Definition | |||||

| Formal Employment | 18,614,899 | 13,209,877 | 5,405,022 | 6,881,347 | 11,733,552 |

| Informal Employment | 27,459,550 | 17,520,000 | 9,939,550 | 10,355,356 | 17,104,194 |

| Percent Informal Sector | |||||

| Formal Employment | 73.2 percent | 73.8 percent | 71.8 percent | 80.4 percent | 68.8 percent |

| Informal Employment | 26.8 percent | 26.2 percent | 28.2 percent | 19.6 percent | 31.2 percent |

| Percent Informal Work | |||||

| Formal Employment | 40.4 percent | 43.0 percent | 35.2 percent | 39.9 percent | 40.7 percent |

| Informal Employment | 59.6 percent | 57.0 percent | 64.8 percent | 60.1 percent | 59.3 percent |

Notes: These stocks are average quarterly data from 2005 to 2012.

This is strong evidence that informality, as defined by the concept of informal sector, was undoubtedly underestimated for all groups but in especial for female and young workers. The reason behind this is the design of the new concept of informal work defined by the ILO and described by Hussmanns (2004). The concept of informal sector only considers the dimension of type of production unit, which comprises private unincorporated enterprises barely separable from the household or owners. The ILO report by Hussmanns includes the dimension of status of employment now including several workers that are effectively informal such as unpaid family members and employees which may be working in either formal or informal enterprises, as well as independent workers working informally. Therefore, many women undertaking work as household helpers in urban areas, self-production in rural areas, salaried workers for small informal businesses, unpaid workers, among other jobs are now considered informal. On the other hand, male and senior workers were less affected by the new categorization, and still occupy the majority of formal positions in the labour market. What these statistics show is the possible precarious situation of women and youth in the Mexican labour market.

This new categorization now includes activities that were previously overlooked and expands the population who is considered informal, though this expansion is different in size for diverse groups of individuals. The interesting question is not whether the new concept of informal work comprises a larger universe of informal activities but whether the individuals now included are similar in behaviour to those already classified as informal. This paper does not intend to deal with this question in deep, but rather to use aggregate flows in order to observe important differences (or similarities) among job categories and groups of workers. The use of gross flows might only offer some indirect evidence about the differences in dynamic behaviour.

II. Gross flows of formal and informal workers

The question is whether the inclusion of the new definition of informal work might bring about important changes in the estimation of gross flows and transitions in the Mexican labour market. This section includes new estimations of unadjusted1 gross flows for both definitions of informality in the Mexican labour market. Unadjusted gross flows have the disadvantage of some loss of information due mainly to non-random reasons which is about 1/5 in the ENOE every quarter. Although adjusted gross flows correct for missing observations, unadjusted data may also produce acceptable results.2 The information from unadjusted gross flows is still of much importance and the transitions might not be so different after adjustment.3

Table 2 presents the average gross flows for the Mexican labour market, using microdata from 32 quarters (sets) from 2005 to 2012 and the convention that the flow is dated up-front the immediate quarter.4 The gross flows are estimated for both informal sector workers and informal workers. There is also estimation of gross flows by gender and age groups. In this paper, the group of young workers is defined up to 29 years old rather than the 25 year-old limit.5 Every worker was matched in every quarter by identification series given in the ENOE by individual and household. Additional series were constructed to identify each individual by age and gender.

Table 2: Average quarterly flows 2005-2012.

| Total | Old | Young | Female | Male | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informal Sector | |||||

| EFEI | 2,717,208 | 1,922,740 | 794,469 | 816,546 | 1,900,663 |

| EFN | 3,446,818 | 2,103,831 | 1,342,987 | 2,207,275 | 1,239,543 |

| EFU | 596,599 | 289,326 | 307,273 | 192,132 | 404,467 |

| EIEF | 2,741,652 | 1,906,269 | 835,383 | 823,355 | 1,918,297 |

| EIN | 2,188,926 | 1,475,936 | 712,989 | 1,537,879 | 651,047 |

| EIU | 294,565 | 170,651 | 123,914 | 59,942 | 234,623 |

| NEF | 3,566,003 | 2,074,219 | 1,491,784 | 1,926,176 | 1,639,828 |

| NEI | 2,237,866 | 1,477,514 | 760,353 | 1,442,333 | 795,534 |

| NU | 562,962 | 213,698 | 349,264 | 315,662 | 247,300 |

| UEF | 612,592 | 287,016 | 325,576 | 207,474 | 405,117 |

| UEI | 303,429 | 179,064 | 124,365 | 63,706 | 239,723 |

| UN | 513,894 | 220,363 | 293,531 | 315,625 | 198,269 |

| Informal work | |||||

| EFEI | 2,688,262 | 1,928,678 | 759,584 | 836,865 | 1,851,397 |

| EFN | 4,374,103 | 2,720,010 | 1,654,094 | 2,914,359 | 1,459,745 |

| EFU | 579,771 | 301,847 | 277,924 | 155,141 | 424,630 |

| EIEF | 2,643,512 | 1,948,297 | 695,215 | 832,727 | 1,810,784 |

| EIN | 1,261,640 | 859,757 | 401,883 | 830,795 | 430,845 |

| EIU | 311,392 | 158,129 | 153,263 | 96,932 | 214,460 |

| NEF | 4,518,152 | 2,705,112 | 1,813,041 | 2,707,054 | 1,811,098 |

| NEI | 1,285,871 | 846,660 | 439,211 | 661,546 | 624,325 |

| NU | 563,014 | 213,700 | 349,314 | 315,668 | 247,346 |

| UEF | 606,216 | 317,335 | 288,882 | 167,837 | 438,379 |

| UEI | 309,650 | 148,705 | 160,945 | 103,251 | 206,399 |

| UN | 513,707 | 220,312 | 293,395 | 315,531 | 198,176 |

Comparing the estimates in Table 2, it can be observed that some gross flows from the new definition of informal work do not change substantially in regard to the gross flows using the old concept of informal sector. The flows from employment to inactivity and back (EFN, EIN, NEF and EIN) account for the largest changes in absolute terms for all groups. The flows EFN and NEF using the new concept of informal work increased almost one million, while the flows EIN and NEI decreased almost one million. The flows EFEI and EIEF are almost unchanged, with only small reclassifications among groups.

The flows un and nu did not change and the very small differences observed in Table 2 between un and nu flows are possibly due to reclassification within the survey and do not affect the analysis.

Although the remaining four total flows (EFU, UEF, EIU and UEI) do not change significantly, there are some important changes among groups. The flows EIU and UEI do increase substantially for women and young workers while male and senior workers decrease. The EFU and UEF flows also have an important decrease for female workers. From all groups, female workers gross flows are the most affected by the new categorization of informality.

The new definition of informality increased the transitions from formal employment to any other labour status (PEFEI, PEFN and PEFU) while it decreased the transitions from informal work to any other labour category (PEIEF, PEIN and PEIU). The probabilities most affected by the new definition of informality are PEIEF and PEIN which saw a sharp decrease for almost all groups. There are some interesting cases where the flow from formal employment to unemployment (EFU), for young workers, has increased while the same flow for old workers changed to opposite direction. The UEF increased for veteran workers and decreased for young workers under the new definition. We also observed a reversal in relative size on the UEI flow for old and young workers.

With the new concept of informal work the transitions PEIEF, PEIN, PEIU and PNEI decreased for all groups and the PUEI decreased for old and male workers. The only transition related to informal work that slightly increased for all groups is the PEFEI. The transitions PUEF and pun remained the largest among all transitions and groups, but male workers had the largest PUEF and the smallest pun among groups. Still male and old workers had the higher probabilities to move into employment, either formal or informal. Women still continued to have the largest chance to move into inactivity from all situations. But one important change is that, young and female workers have the highest probability to move into unemployment from employment, either formal or informal, due to reclassification.

With the new concept of informality, the analysis of gross flows shows that the probability to move into informality is still larger for male and senior workers. Similarly, the probability of becoming inactive is larger for young and female workers. The results from the aggregate gross flows and the transitions do not display critical contrast between workers in the informal sector and informal workers proper.

There are some slight differences in terms of the size of gross flows for some groups of workers. There is a trade-off among groups but also among labour categories. Workers that previously were considered unemployed or formal are now classified as informal workers. In general, the probabilities of becoming informal and inactive increased more for women while the probabilities to get a formal job decreased. The relative position in terms of transitions probabilities for male and senior workers improved in exchange.

Table 3: Transitions.

| Total | Young | Old | Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informal sector | |||||

| PEFEI | 0.095 | 0.089 | 0.098 | 0.107 | 0.076 |

| PEFN | 0.121 | 0.151 | 0.107 | 0.070 | 0.206 |

| PEFU | 0.021 | 0.034 | 0.015 | 0.023 | 0.018 |

| PEIEF | 0.244 | 0.267 | 0.235 | 0.288 | 0.180 |

| PEIN | 0.195 | 0.228 | 0.182 | 0.098 | 0.337 |

| PEIU | 0.026 | 0.040 | 0.021 | 0.035 | 0.013 |

| PNEF | 0.122 | 0.120 | 0.125 | 0.210 | 0.090 |

| PNEI | 0.077 | 0.061 | 0.089 | 0.102 | 0.068 |

| PNU | 0.019 | 0.028 | 0.013 | 0.032 | 0.015 |

| PUEF | 0.350 | 0.353 | 0.348 | 0.384 | 0.300 |

| PUEI | 0.174 | 0.135 | 0.217 | 0.227 | 0.092 |

| PUN | 0.294 | 0.318 | 0.267 | 0.188 | 0.456 |

| Informal Work | |||||

| PEFEI | 0.114 | 0.098 | 0.122 | 0.128 | 0.092 |

| PEFN | 0.186 | 0.214 | 0.172 | 0.101 | 0.319 |

| PEFU | 0.025 | 0.036 | 0.019 | 0.029 | 0.017 |

| PEIEF | 0.163 | 0.161 | 0.164 | 0.180 | 0.136 |

| PEIN | 0.078 | 0.093 | 0.073 | 0.043 | 0.136 |

| PEIU | 0.019 | 0.035 | 0.013 | 0.021 | 0.016 |

| PNEF | 0.155 | 0.146 | 0.162 | 0.232 | 0.127 |

| PNEI | 0.044 | 0.035 | 0.051 | 0.080 | 0.031 |

| PNU | 0.019 | 0.028 | 0.013 | 0.032 | 0.015 |

| PUEF | 0.347 | 0.313 | 0.385 | 0.415 | 0.242 |

| PUEI | 0.177 | 0.174 | 0.180 | 0.195 | 0.149 |

| PUN | 0.294 | 0.318 | 0.267 | 0.188 | 0.456 |

III. Cyclical analysis of gross flows

Another way to visualize the differences between these groups of workers is to observe the gross flows over time. A cyclical analysis helps us to understand how individuals move among labour categories, depending on the phase of the business cycle. For example, more workers may move into unemployment during recession and back to employment during economic recovery. An initial graphical analysis is helpful for an initial examination.

Furthermore, we analysed the cyclical components of the flows and hazards using a simple time series analysis. We regressed the flows and hazards on a cyclical variable, in this case, the growth rate of real GDP. We detrended the series using a polynomial function on time and used quarterly dummies in order to discount for seasonal components as in Gallardo Del Angel (2013). Tables 4, 5, 6 and 7 show the estimates for the cyclical components, detrended and net of seasonal dummies.

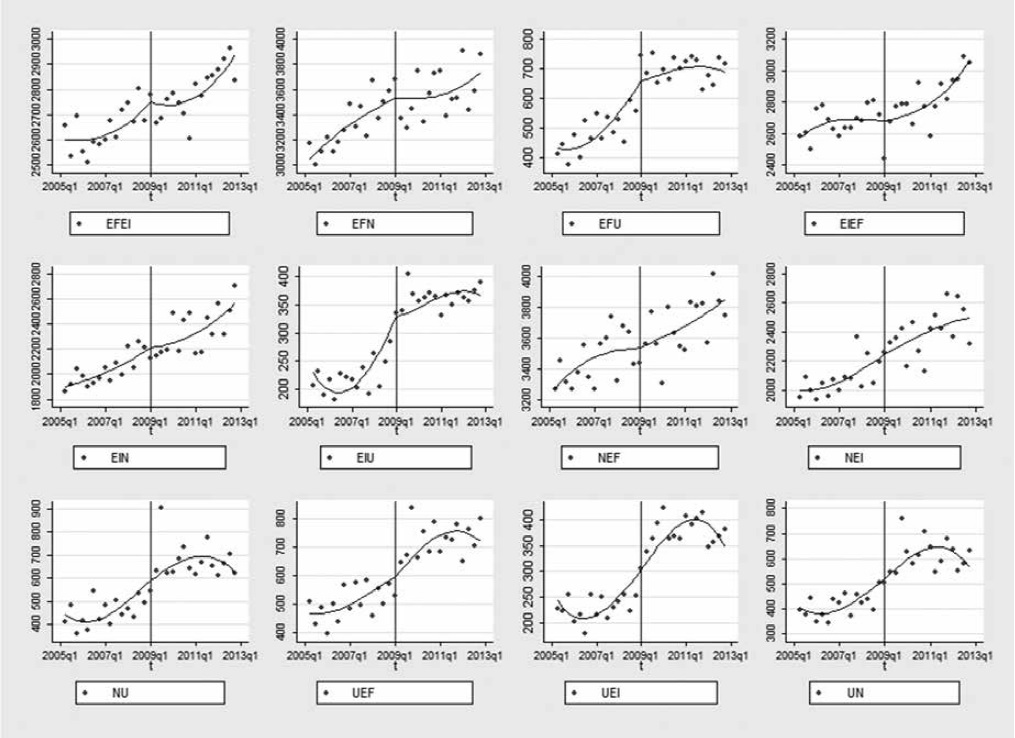

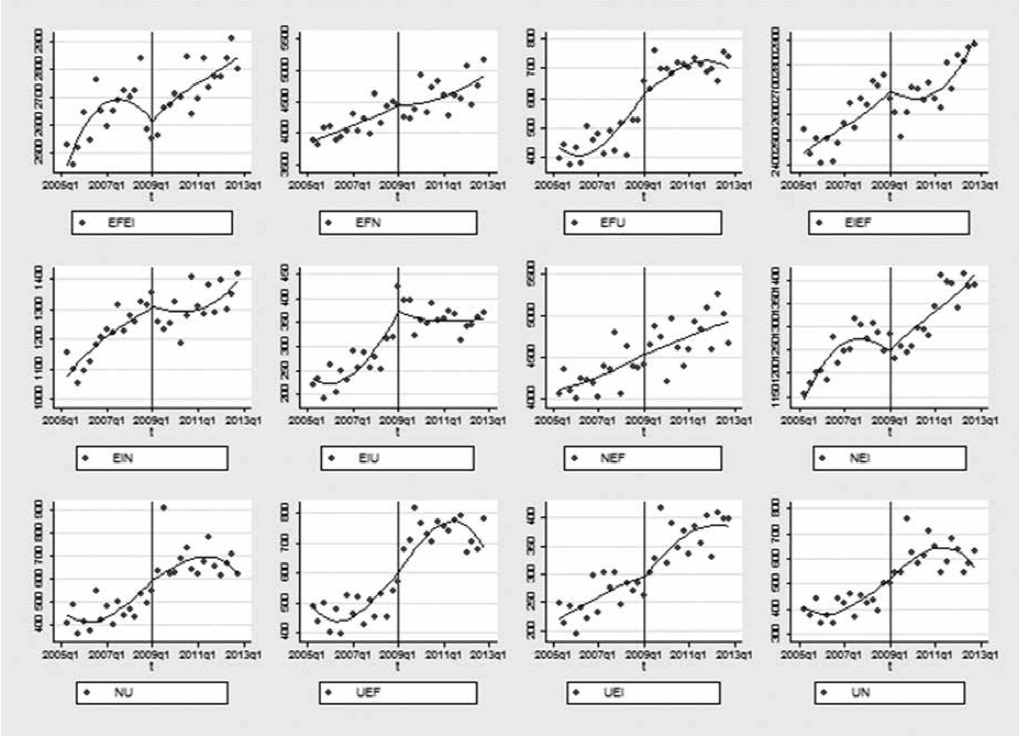

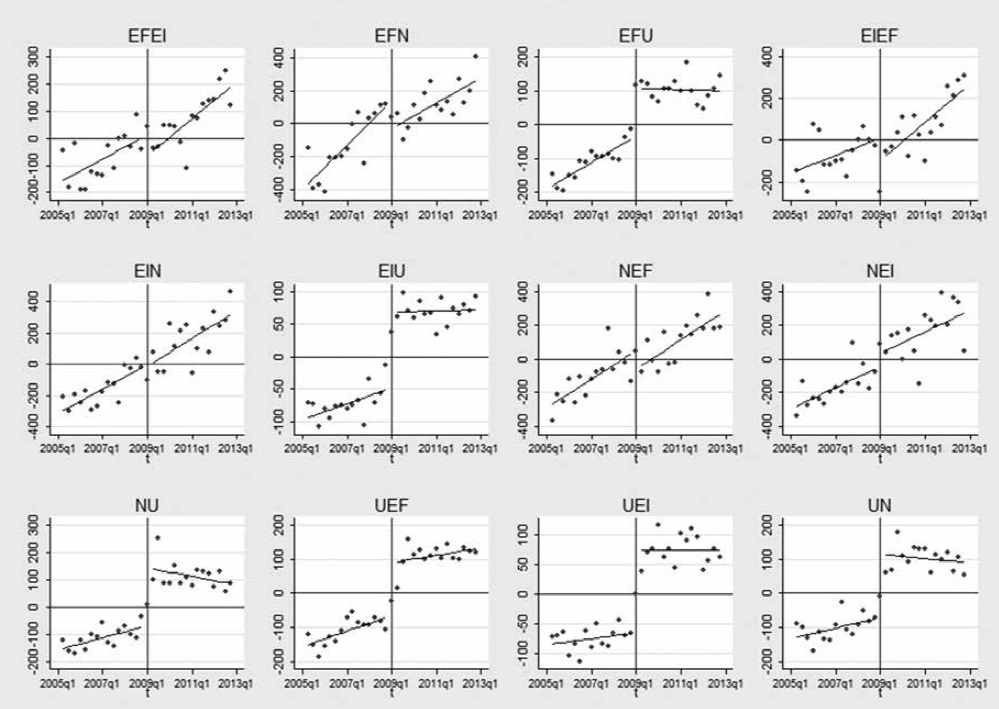

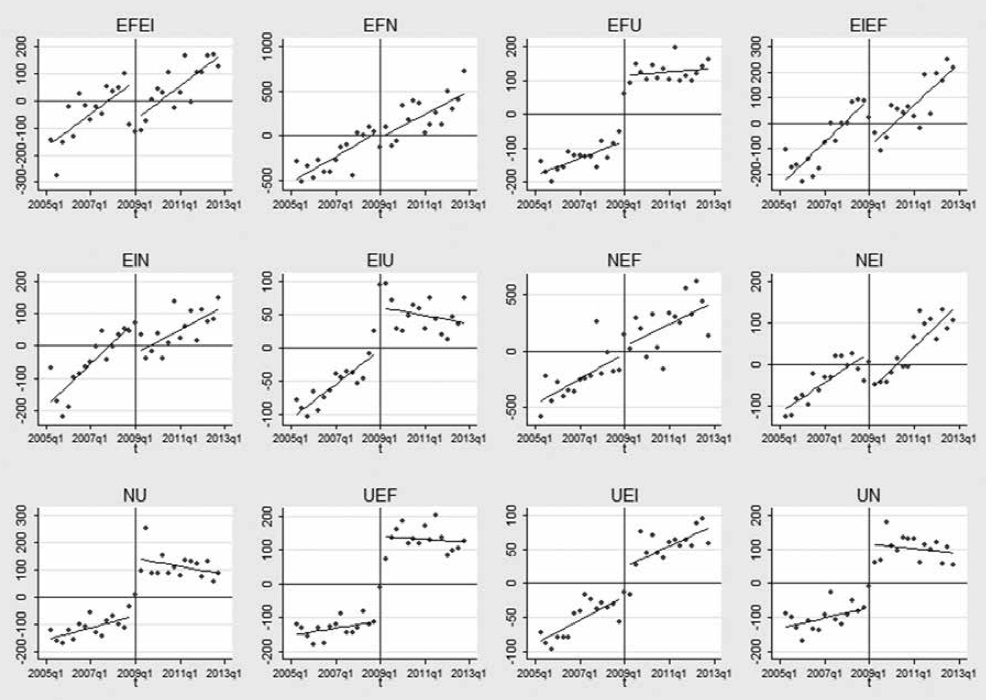

Figures 1 to 4 in the appendix show scatter plot graphs of the gross flows and transitions during the eight years period of 2005 to 2012, using a polynomial spline and linear fits to observe the movements of the flows along the business cycle. A vertical line is added to the plots in order to observe the flows and transitions during recessive and recovery parts of the cycle. We made the splines discontinuous from the quarter when the GDP of Mexico had the lowest real growth rate (the vertical line).

Although the level of gross flows is different in every graph after the new categorization, the overall trend of the flows remains very similar under both concepts of informality. The only exceptions are the flows EFEI, EIU and NEI which are little different but keep similar trend. Still it is possible to observe that most flows into and out of unemployment (EFU, EIU, NU, UEF, UEI and UN) are mainly countercyclical and show a distinctive italic-style “S” shape spline. The conclusion is that the flows in and out of unemployment increased during recession and decreased during economic recovery. In this respect, both concepts of informality are much alike.

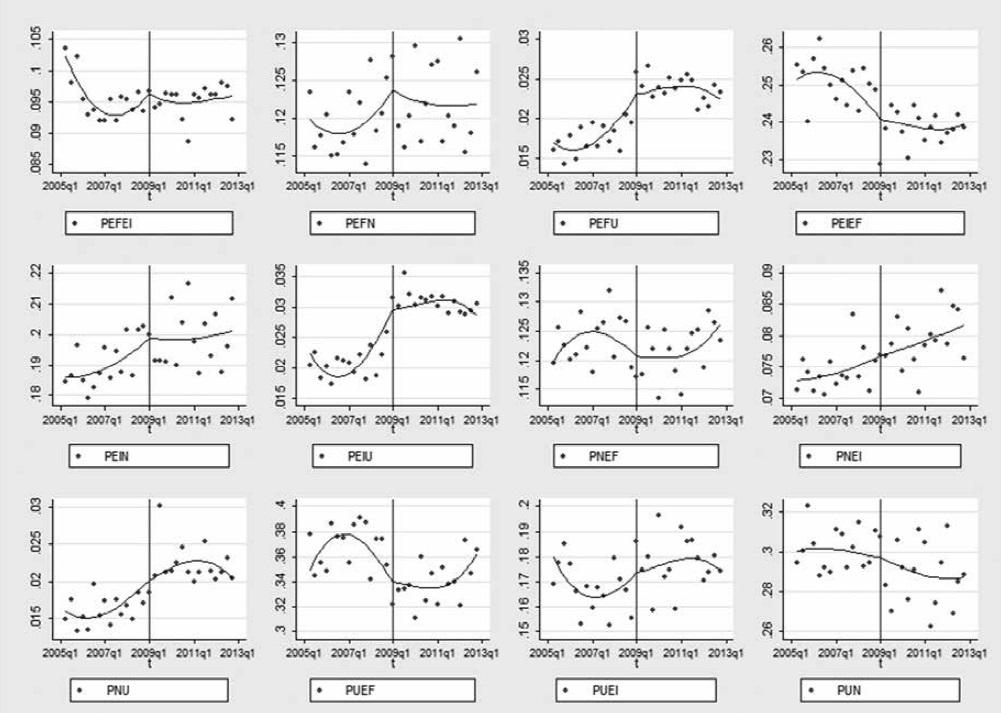

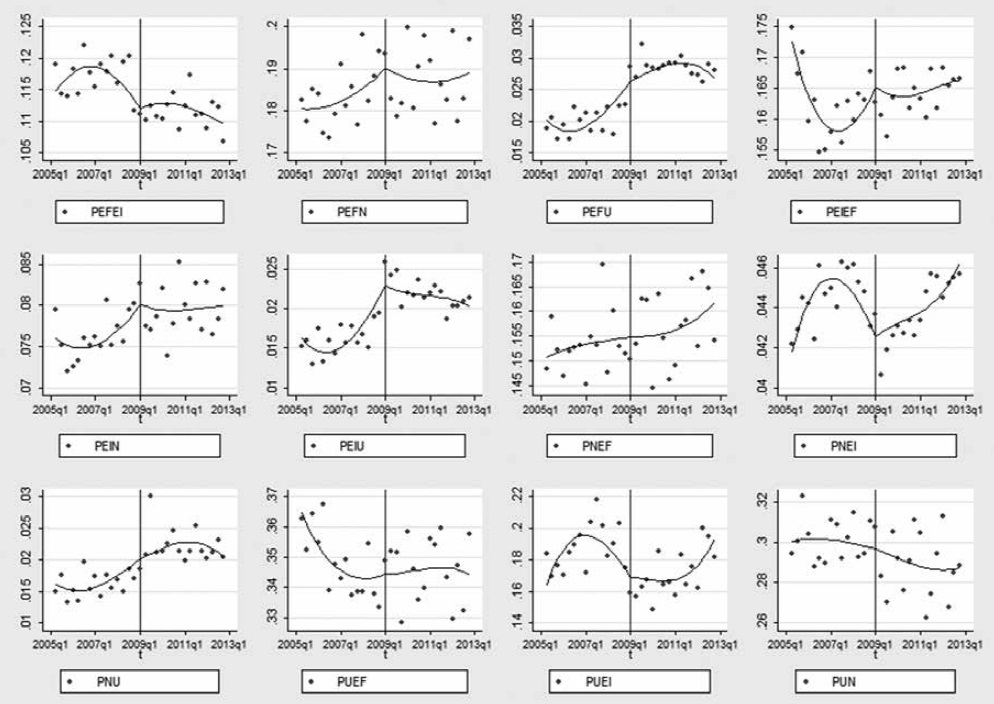

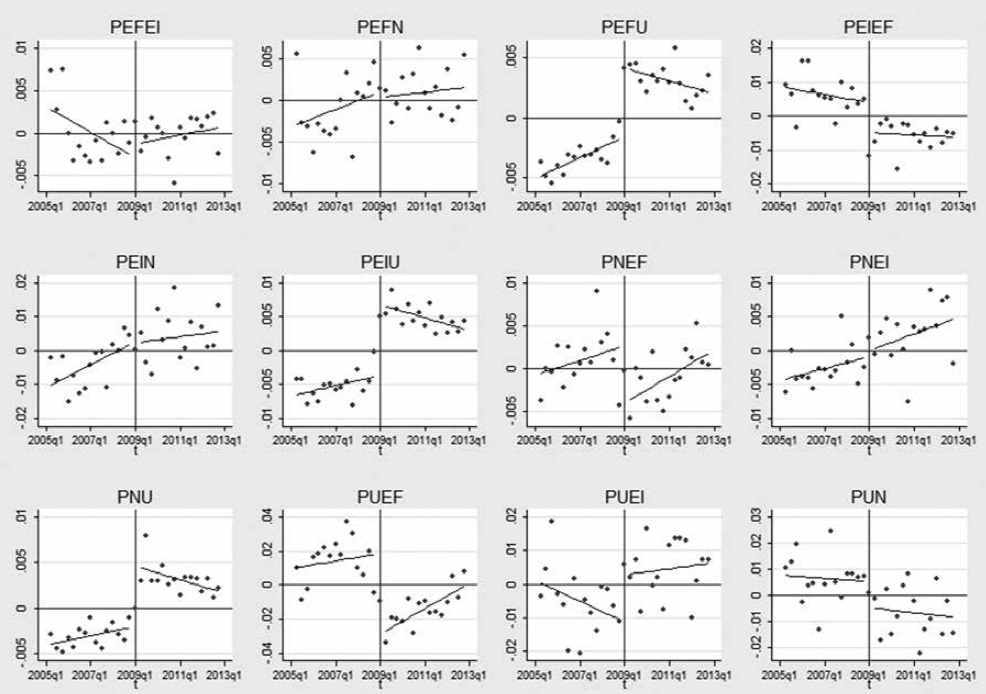

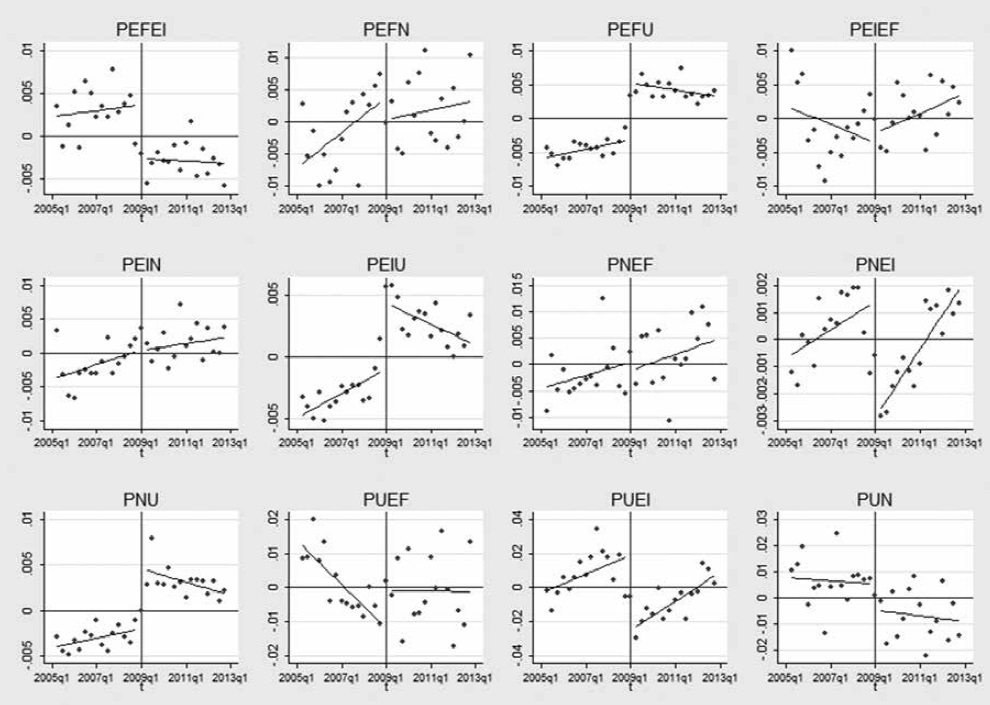

The graphical analysis of Figures 3 and 4 shows that the new categorization changed the transitions probabilities for all flows (except the PNU and PUN that are not affected by the new concept of informality). The transitions PEFEI, PEIEF, PNEF, PNEI, PUEF and PUEI showed changes from countercyclical to pro-cyclical shapes.

Figures 5 and 6 show the gross flows net of seasonal dummies for both concepts of informality. Also a vertical line is added to highlight recession and recovery periods. In these graphs, the horizontal axis divides the negative and positive flows and hazards net of seasonal components. Linear fits on the quadrants allow for cyclical analysis. If flows are counter cyclical they must be negative but increasing in the third quadrant and positive but decreasing in the first quadrant. Rather than a cubic spline a linear fit is included for both the recession and the recovery phases of the business cycle. Graphs 5 and 6 show that both concepts are similar in trend and shape. The gross flows EFU, EIU, nu, UEF, UEI and un still show some signs of counter-cyclical movement along the business cycle, with negative flows net of seasonal components in the third quadrant and positive flows in the first quadrant. There are some slight changes in the slope of the flows but in general gross flows into and out of unemployment behave as predicted by theory.

Although there is a trade-off in terms of gross flows in the labour market due to the new categorization, transitions do change as shown in Figures 7 and 8. In aggregate, the transitions PEFN, PEFU, PEIN and PEIU are similar between both concepts of informality. The transitions PEFU, PEIU and PNU still show some evidence of counter cyclical components after the new categorization.

The problem with the graphical analysis is that it is hard to get a detailed view of the problem when there are so many flows, categories and groups. A more compacted analysis is needed to appreciate the real dynamic characteristics of the flows. In order to improve our understanding about the gross flows and transitions, a standard statistical analysis is needed to confirm the trends shown in the graphical analysis and to detect cyclical properties of the gross flows and transitions.

A standard dummy variable model was used to capture dynamic properties of the gross flows for earch definition of informality and by groups. The gross flows and transitions were regressed on quarterly dummies, a cubic time variable and a variable that contains information about the business cycle. The real GDP growth rate was used for capturing the information on the business cycle. The coefficient of the variable real GDP growth was used to interpret the dynamic properties of the gross flows and transitions. Tables 4, 5, 6 and 7 at the end of the appendix show the estimation. Every table contains the value of the coefficient on the cyclical variable for each gross flow and transition, repeating the estimation for both definitions of informality.

The results from Tables 4 and 5 confirm that gross flows into and out of unemployment are counter-cyclical. Under the definition of informal sector the flow UEI was counter-cyclical for all groups, but under the new definition of informal work the flow UEI is only significant for senior workers and the ow UEF is significant for all groups except female workers. Another interesting result is the change for the old pro-cyclical gross flows EFEI and EIEF for young workers. Under the new categorization, only EFEI is pro-cyclical for the total, young and male workers. A new pro-cyclical gross flows is the flow NEI for female workers.

The adjustment induced by the new definition of informal workers can be better appreciated in Tables 6 and 7. Under the old definition of informal sector most transitions into formal employment were showing pro-cyclical components. With the new definition of informal work, the transitions into informal work are pro-cyclical. This is an important information because the probability to become informal decreases with the recession and increases with the recovery. The transitions into formal employment are not significant at all under the new concept of informal work.

Concluding remarks

The new definition of informal work changes the level of gross flows and transitions for all groups, but female workers seems to be the more affected by the new categorization of informality in terms of absolute changes in the flows and transitions probabilities. In general, gross flows in and out of inactivity are large for Mexico compared with other economies like US or Canada. This conclusion continues to hold despite the changes in definition of informality. Following the findings of Gallardo Del Angel (2013), female and young workers have the highest risk of becoming inactive while male and senior workers have the largest probabilities of becoming informal from any labour market category. Female workers are still the least affected group by the business cycle compared with other groups.

Under the definition of informal sector many of the transitions into formal employment were pro-cyclical. This situation changed with the new categorization when the transitions into informal work became pro-cyclical while those into formal work are not significant any more.

With all this information at hand, some doubts are cast on the nature of informal work. The groups such as female and young workers still have higher probabilities to move into inactivity rather than informal work. On the other hand, male and senior workers have higher probabilities to move into informal work. This raises the question of whether there is any difference in the nature of informal and formal work. The new categorization only affects the probabilities to become informal, which moves in the same direction as the business cycle.

The new concept of informal work includes workers that were previously ignored by the concept of informal sector. Estimation of workers flows and transitions probabilities for Mexican workers are improved under the new categorization. Workers such as informal employees, household employees and household members employed in family informal enterprises, among others, are now included in the statistics. Most of the overlooked informality were comprised by female and young workers for which gross flows and transitions are now better understood. Transitions into not-in-the-labour-force are particularly large for these groups of workers and attention from policy makers should be paid to these groups.

In terms of cyclical components, female workers are less affected by the business cycle. Unemployment is countercyclical and most workers flows into and out unemployment has a negative cyclical component. Other flows in and out of informality are also countercyclical with the exception for EFEI which is pro-cyclical. The flow NEI is pro-cyclical for young and female workers and countercyclical for male and veteran workers. The flow UEI is only countercyclical for veteran workers. Previously, most significant gross flows were countercyclical, especially those into unemployment and informality.

On the other hand, with the previous concept of informal sector, transitions into formal employment appeared to be significant and pro-cyclical. With the new concept of informal work the cyclical component into formal employment is not significant any more. Most transitions probabilities into informality now became pro-cyclical (PEFEI, PNEI and PUEI) while the transitions such as PEFU, PEIN, PEIU and PNU are countercyclical. With the new concept of informal work still especial attention must be paid to informal and unemployed which are the most affected by the business cycle.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)