Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Frontera norte

On-line version ISSN 2594-0260Print version ISSN 0187-7372

Frontera norte vol.26 n.51 México Jan./Jun. 2014

Artículos

Indigenous People and Nation-State Building, 1840-1870

Indígenas y construcción del Estado-nación, 1840-1870

Zulema Trejo Contreras

El Colegio de Sonora ztrejo@colson.edu.mx

Fecha de recepción: 7 de marzo de 2013.

Fecha de aceptación: 12 de julio de 2013.

Abstract

The article analyzes the role of the indigenous societies of Sonora in the construction of the Mexican nation-state in the 19th century. On the basis of three analytical axes (land, war and citizenship), it discusses the main perspectives —both theoretical and analytical— under which indigenous people have been presented as coadjuvant agents or obstacles in the establishment of the institutions comprising the Mexican nation-state. By way of a conclusion, the author suggests the need to rethink the impositions placed on these societies and the specific reactions of the latter.

Keywords: indigenous, ethnical minority, nation-state, political history, Mexico.

Resumen

En el presente artículo se analiza la participación de las sociedades indígenas de Sonora en el proceso de construcción del Estado-nación mexicano durante el siglo XIX. Partiendo de tres ejes analíticos (la tierra, la guerra y la ciudadanía) se presentan y discuten las principales perspectivas teóricas y analíticas a través de las cuales se ha analizado el rol de los indígenas como agentes coadyuvantes u obstaculizadores para el establecimiento de las instituciones constitutivas del Estado-nación mexicano. Se presenta como conclusión la necesidad de repensar tanto las imposiciones hechas a estas sociedades como las reacciones específicas de cada una ante las mismas.

Palabras clave: indígenas, minoría étnica, Estado-nación, historia política, México.

INTRODUCTION

Nation-state building1 in Latin America is a process that has only relatively recently attracted the attention of historians, since although more specific phases or events of this process have been researched,2 a comprehensive study of this process had yet to be carried out because of its complexity. Thanks to works such as Ciudadanía política y formación de las naciones. Perspectivas históricas de América Latina (Sabato, 1999); Federalismos Latinoamericanos: México/Brasil/Argentina (Carmagnani, 1996); La integración del territorio en una idea de Estado, México y Brasil, 1821-1946 (Ribera, Mendoza and Sunyer, 2007) and Convergencias y divergencias: México y Perú, siglos XVI-XIX (Oliver Sánchez, 2006), to name just a few, gradual progress has been made in learning how nation-state building took place in each country, going beyond the biographies of great men and monographs on military exploits in conflicts regarded as crucial in each national history, such as the Reform War in Mexico, the War of the Supreme in Colombia and the Desert Campaign in Argentina.

In the case of Mexico, the historiography related to the process of nation-state building has been constantly present since the 1960s. These early works include El liberalismo mexicano (Reyes Heroles, 1974); La supervivencia política novo-hispana, monarquía o república (O'Gorman, 1986); El liberalismo mexicano en la época de Mora 1821-1853 (Hale, 1978) and La Transformación del liberalismo en Mexico a fines del siglo XIX (Hale, 2002);3 these early works are general studies in which the establishment and consolidation of the liberal project are linked to the establishment of Mexico as a nation and state. It is only recently that works specifically related to the construction of the Mexican nation-state have been published, such as La definición del Estado mexicano 1857-1867 (Galeana, 1999); Estado-Nación en Mexico: independencia y revolución (Márquez, Araujo and Ortiz, 2011) y Poder y legitimidad en Mexico en el siglo XIX (Connaughton, 2003). These works are compilations of articles covering a range of topics, revolving around the process of nation-state building in Mexico. This process is viewed from the various regions comprising the country and from a series of specific events that catalyzed and/or delayed it. A one-way vision predominates in this work because it basically takes into account the participation of white-mestizo society, ignoring the contribution of indigenous groups, except when their participation is regarded as part of the armies that fought in the struggles characteristic of the political environment of the 19th century.

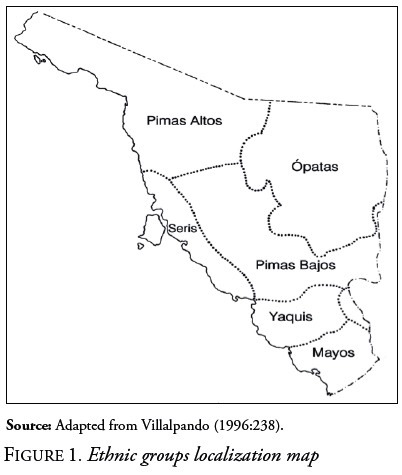

Given the above, the following article undertakes a preliminary analysis of the participation of indigenous societies in the process of constructing the Mexican nation-state. This initial approach is limited to the case of indigenous groups in Sonora, particularly the Ópatas, Yaquis and Mayos. While it is true that the construction of the nation-state is a general process involving a wide range of actors, the case study described below is important, since the focus of analysis is on the participation of indigenous societies in this process, thereby contributing to increasing the complexity of the one-way perspective that has prevailed to date, in other words, one that considers the construction of nation-states as an almost exclusive process of white-mestizo society, in order to make it more inclusive. The analysis of the participation of the ethnic groups of Sonora in the establishment and consolidation of the Mexican nation-state is inserted into the framework of national issues, so that the contributions of Sonoran indigenous societies to this process are not seen as an isolated or exceptional element. Just as the participation of white-mestizo society in the process of constructing national states has multiple facets, that of indigenous societies is also multidimensional. This paper focuses on three of these dimensions, namely territory, war and citizenship in Yaqui, Ópata and Mayo societies, in order to contrast them to determine the differences or similarities between each case. This comparison is designed to show that the participation of indigenous societies in the construction of the nation-state has as many nuances and aspects as that of white-mestizo society. It is also intended to show that examining the construction of national states from an indigenous perspective is not a divergent approach, but rather a complementary one to those that exist at present.

ÓPATAS, MAYOS AND YAQUIS

According to Yetman, among the indigenous people living in the territory known as Opatería, from the time of contact with Spanish society, "There were probably [three] or more distinct groups: the group that became to be called Teguimas and subsequently Ópatas, the Eudeves, and the Jovas [...]" (Yetman, 2010:15). As for their habitat, the author declares: "[the] Ópatas lived in narrowish valleys of desert rivers —the Bavispe, the Mátape, the Moctezuma, the San Miguel and the Sonora [...]" (Yetman, 2010:20).

Historiography has characterized the Ópatas as the most docile ethnic group and the one most willing to relate to white-mestizo society. A prime example of this willingness to coexist with the Spanish first and then the mestizos is the incorporation of these Indians initially into the military forces of the colony and subsequently as national forces as assistant companies to the Crown and the national army respectively. During the19th century, the process of cultural exchange taking place between Ópatas and non-indigenous people, reflected in matters such as the use of Spanish and clothing worn by non-indigenous people, was consistently documented.

The Mayo continue to live in southern Sonora. Their original settlement was located on the Mayo river banks, after which they were named, but as the indigenous groups inhabiting the sierra and northern zone of the current state of Sinaloa (Moctezuma and López, 2007:6) became extinct, the Mayos expanded the boundaries of their territory to these areas.

The relationship between Mayos and white-mestizo society during the 19th century was midway between the conciliatory attitude of the Ópatas and the open rebellion of the Yaquis. This is borne out by the fact that the expansion of private ownership of land in the Mayo Valley occurred at a faster rate than in the case of the Yaquis. This does not mean that the Mayos had been permanently at peace, although their uprisings have barely been studied, except for the last one, which revolved around Teresa Urrea, better known as the Saint of Cabora. Primary sources contain considerable information, which shows them leading armed conflicts, as in the case of the rebellion led by Miguel Esteban in the 1840s.4 The Yaquis currently inhabit the south-central region of the state of Sonora in their eight traditional villages: Cócorit, Bácum, Tórim, Vícam, Pótam, Huírivis, Ráhum and Belem. Due to the diaspora caused by deportation, a number of Yaqui groups settled in Hermosillo and others in Arizona (Padilla and Trejo, 2012:195 and 201). During the 19th century, Yaqui towns were basically indigenous with few or no white-mestizo inhabitants, depending on the town involved. For example, Cócorit and Bácum used to be inhabited by nonindigenous groups. This information came to light during uprisings, since these people were the first to be targeted by rebellious indigenous groups.

Like the Ópatas and the Mayos, Yaquis were engaged in subsistence agriculture. They used to be employed on farms, mines, fished and exploited the salt mines within their territory. Unlike the ethnic groups mentioned above, the Yaquis engaged and continue to engage in a constant struggle for possession of the Yaqui Valley; this fight has had several variants ranging from armed conflict to negotiation with equally disparate results: wins, losses, mass shootings, massacres and deportation.

As shown in the preceding paragraphs, among the indigenous societies that are the subject of this article, there were similarities and differences reflected in the ways they reacted to the process of the construction of the nation-state. As will be discussed in the following pages, these discriminating factors will serve to contrast the way the axes of earth, war and citizenship were used by each of the indigenous groups mentioned in the preceding paragraphs to help or hinder the establishment and consolidation of the Mexican nation-state.

THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE NATION-STATE FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF INDIGENOUS PARTICIPATION

The participation of indigenous societies in the construction of nation states is a topic that is practically absent in the historiography of Latin American countries, which is understandable given the complexity of this process comprising a wide variety of facets and actors. Now that research from previous years has cleared the way and clarified the big picture, it is possible to advance knowledge on the contribution of ethnic groups to this crucial process for the historical development of current Latin American nations. In Sonora, indigenous participation in the process of constructing the nation-state occurred on the basis of three axes: territory, war and citizenship. To date, the first two axes have attracted the most attention; the third is only beginning to be studied.

Land: Common bond and bone of contention

Land ownership is an element that cannot be ignored when analyzing 19th century societies, since for Indians, Creoles and mestizos, owning land was crucial to survival, the accumulation of wealth and the acquisition of social prestige (Moreno, 1994:259). Moreover, several 19th century laws and conflicts of the nineteenth century were woven around this element.5 Given these premises, land ownership should be considered a central element in the construction of the nation-state, especially when analyzed from the perspective of indigenous societies, since for them their relationship with the land goes beyond the fact of possessing it, in the sense of being its owners, since they consider it part of themselves, of their indigenous self,6 at least in the case of ethnic Yaquis (García Wikit, 2003:11-13) and other indigenous groups in Sonora. Since they regard the earth as part of themselves, the grievances suffered by indigenous societies due to 19th century government measures designed to expropriate them, or modify the way they possessed them, was expressed in a series of rebellions, alliances or legal measures that formed and lent shape to the construction of the Mexican nation-state.

In the case of Sonora, land and indigenous people should be discussed from two points of view: One is the armed struggle in defense of their territories; the other is the possession of the land as the basis of alliances between whites/mestizos and indigenous peoples; these two aspects constitute the first of the three axes raised above. It is worth remembering that the following analysis will be guided by the axes mentioned in the introduction rather than on indigenous societies. These will be included in the analysis based on the way they responded to the measures described in the aforementioned analytical axes.

Core Issues

The latest historiography from Sonora7 shows that the armed opposition of indigenous groups in defense of their territory was linked, on several occasions, to colonization projects that the Sonoran government attempted to implement. The clearest example was what happened in the Yaqui and Mayo valleys; in these areas the government, headed by Ignacio Pesqueira,8 attempted to establish colonies in order for the fertile lands in these valleys to be cultivated intensively. However, his plans met with opposition from the Yaquis and Mayos. The best documented conflicts are those in which the Yaquis are involved;9 little if anything has been written about the Mayos specifically regarding this topic.10

Regarding the Yaqui Valley, the most emblematic case is the conflict caused by the possession of the land of Aguacaliente, begun in 1854 and ended over a decade later. This event involved the Yaquis and one of the leading families in the state, the Íñigo. In 1854, Fernando Iñigo denounced these lands, which were awarded to him. However, the Yaquis protested to Governor Manuel María Gándara, who ordered a halt to the process of allocating land to Íñigo. The Yaquis continued to possess Aguacaliente until 1868, the year that President Benito Juárez granted them to Colonel Jesús García Morales, the Republican hero of the struggle against the Second Empire, who denounced them as vacant land in the late 1850s (Revilla, 2012).

In the case of the Mayos, there is no conflict as clear as that narrated in the preceding paragraph. During the period analyzed in this paper, several rebellions by this ethnic group were recorded but none has been unequivocally linked to the struggle for possession of Mayo Valley. The documentation on these uprisings does not specify the reasons that led to them. For example, in 1859, when the establishment of the "Pesqueira" neighborhood was decreed in Mayo Valley, there are no records of an armed confrontation, nor have instances been located of protest by this ethnic group directed at the governor or the prefect of the district of Álamos, the authority with jurisdiction over the lands where the colony was established. Moreover, records of protests (whether peaceful or violent) by the Mayos closest to 1859 are those that occurred in 1861 and 1862, which are related to state political events such as the signing of acts of accession or the repudiation of any of the factions of notable figures engaged in war at the time.

The events mentioned in the previous paragraph show that no reliable proof has been found to date that in the case of the Mayos, their rebellions were closely linked to the defense of their territory. It is extremely likely that this was so, however, since the years studied in this paper were characterized by continuous outbreaks of violence in Mayo Valley. In fact, the Álamos National Guard was engaged in an almost permanent campaign against this ethnic group, and it is no coincidence that precisely at this time, the first stage of colonization by the leaders of Álamos was taking place.11

Contrary to what happened south of the state, in the northwest and northeast, the Ópata did not offer armed opposition to the loss of their territory, although they did protest to the state and national government through representatives (Radding, 1995; Trejo 2010).12 The peaceful protest by the Ópatas and lower Pimas13 is proof of their insertion in the process of creating the nation-state, since they appealed to the liberal laws, which, although they did not favor them as regards their right to the corporate ownership of lands inherited from missions, they did establish the distribution of individual plots of land which the Ópata defended continuously at least until the beginning of the 1870s.

In Sonora, the land became a link between the Yaquis/Mayos and a select group whose contemporaries called them Gandaristas. The Indian-Gandarista dyad has been regarded by the historiography of Sonora as an obstacle to the liberal project, symbolized in the figure of Governor Ignacio Pesqueira and his allies (Ruibal, 1985; Villa, 1984), since the indigenous people used their alliance with General Manuel María Gándara to offer both armed and peaceful resistance to the projects for setting up colonies in their valleys (Revilla, 2009).

From this perspective, the opposition between the Mayos and the Yaquis constituted an obstacle in the implementation of the liberal project, which at the same time, slowed down the process of the national state, since by preserving their valleys, these two indigenous groups in Sonora continued to preserve their own forms of government, military structure and recreated religious practices, all of which went against the homogenization demanded by the construction of a nation-state in which the citizen rather than the corporation and individual rather than communal ownership of the land should become the center of the modern society which attempts were being made to create.

The perception of the Indigenous-Gandarista alliance has a second dimension that is usually ignored, in other words, Manuel María Gándara's attempts at colonizing the Yaqui Valley. Like his opponents, Gándara designed a project to colonize the Yaquis, except that he did not feel it was necessary to dismantle communal property or evict indigenous groups to implement it (Trejo, 2011). Gándara's proposal involved securing the Yaquis' approval to loan part of their lands to a group of settlers. If this project had been implemented, it would have had a significant influence on the creation of the Mexican nation-state, since it would have great possibilities of continuing to pacify the Yaquis and ensuring that their lands produced a surplus for commercialization, which, in the last analysis, was the aim of Sonora notables, since they based their hopes of progress on it,14 since activities such as mining and livestock raising were virtually paralyzed due to the Apache raids (Velasco, 1985).

Land as the basis of the alliance between indigenous groups and the elders is an issue that has barely been explored in Sonoran historiography. Until recently, the opposite view was held, namely that land constituted the element of greatest conflict between Indians and whites. This statement must be qualified because although a fraction of Sonoran notables fought over the earth inhabited by Yaquis and Mayos using weapons, others found that communal land ownership by indigenous peoples served as the basis for building alliances to enable them to face a common enemy (Trejo, 2011; Padilla and Trejo, 2012). The Gandarista-Yaqui alliance, referred to earlier, can only be fully understood by taking into account the importance of the possession of land for both groups.15

Members of the Gandarista faction, starting with their leader Manuel María Gándara, owned some of the largest, most productive farms in Sonora, all located in the center of the state (Trejo, 2008). Many rural properties of the Gandaristas were collective properties, in other words, they belonged to several members of the same family at best, or to several partners who may or may not have been linked to each other by ties of kinship. As a result, the main Sonoran haciendas were collectively exploited, as were the Yaqui and Mayo valleys. Thus, this faction of notables always showed respect for the rights of possession of the Yaquis and Mayos over their respective valleys.

The question one must now ask is whether this implicit agreement over the form of land ownership facilitated or hindered the process of creation of the nation state. If one understands nation-state to be a strictly liberal state, then it certainly hindered it, since the creation of citizens and individual landowners premises was a liberal project, as envisaged in the early 19th century by Benjamin Constant (2000). However, if the corporate ownership of the valleys of southern Sonora had been respected by implementing colonization projects as proposed by Manuel María Gándara in the late 1840s, the Yaqui secular war might have been a shorter, less violent process, and would not have ended with the deportation of Yaquis to Yucatán and National Valley.

Since the land issue was one of the axes around which crucial measures in the liberal project revolved, such as the laws of confiscation and nationalization of property and various colonization projects (Hale, 1978; González, 2000), it is logical to suggest that the response by indigenous societies to this was a key element in the process of constructing the Mexican nation-state, regardless of whether ethnic groups' reaction to the possibility of being colonized and/or having their territory expropriated by whites and mestizos was positive or negative.

The War

The territories known as Sonora from the time of the first contact with the Spanish to the present have had a number of features that differentiate them while assimilating other regions of Mexico and Latin America. The intermittent warfare that took place in this territory is one of them. According to traditional Sonoran historiography, the war against the Apache, Seri, Mayo, Yaqui and Pima groups (the latter in colonial times) is an element that made Sonora a completely different territory from the rest of the regions comprising Mexico.16 The emergence of an armed white society, accustomed to fighting against Indians, filibusters and among itself is certainly a distinctive, important feature of the history of Sonora, which rather than radically differentiating the state from other regions, makes it similar to them.

Beyond the struggle between the notables, or the defense of the territory from filibuster attacks, the war in 19th century Sonora was linked to the conflict between Indians and whites. This relationship has been documented by historiography from two perspectives: the military alliance for dealing with a common enemy, and the armed confrontation between whites/mestizos and Indians. The first approach is rooted in the colonial era, when the Spanish used the Ópatas' and Pimas' skills to deal with the indigenous people who continued to oppose control by the Spanish Crown (Borrero, 2009). The importance of the military aid of the Ópatas was reflected in the creation in the late 18 th century of two Presidios composed exclusively of members of this ethnic group, which were given the status of auxiliary troops. Once independence had been achieved, the Ópata auxiliary troops became auxiliary forces of the national government.

The status of the Ópatas as national government auxiliaries enabled them to preserve the military structure acquired in colonial times, which in turn allowed them to participate actively on the Sonoran political scene, either by supporting or opposing successive governments. Their status as Indian friends, acquired during the time of the Spanish monarchy, allowed them to approach the Sonoran authorities who had no other indigenous groups, as demonstrated by recent work on political representation among the Ópatas.

Apart from the Ópatas' collaboration first with the colonial and subsequently with the Mexican authorities, cooperation between Yaqui and Sonora authorities existed for dealing with a common enemy. In this case it was a momentary alliance between government department troops (at that time, the centralist Republic ruled the country), and the Yaquis to cope with the Mayo rebellion led by Captain General Miguel Esteban. At this point, it is worth noting that once Miguel Esteban had been defeated, Captain General of the Yaquis Mateo Marquín extended his jurisdiction to the Mayos, as the department authorities named him captain general of both valleys, an appointment that was opposed by the Mayos, who six years later continued to complain to the authorities about this appointment (AGES, 1846).

In the case of the Ópatas and the Pimas, their contribution to the construction of the nation state is due to the fact that they adapted more successfully than other indigenous societies to white/mestizo society and its institutions, including the military structure of both the Novo-Hispanic and Mexican authorities. This adaptation enabled them to achieve the social integration desired by the liberal project in order to homogenize the country's inhabitants, making them citizens with equal rights and obligations, without major confrontations.

The armed conflict with indigenous groups that might have had some influence on the formation of the nation-state is the one waged by the authorities with the Yaqui ethnic group for decades. This lengthy conflict is known as the Yaqui secular war.17 The Yaqui secular war has many aspects, whose common thread is the defense of Yaqui territory. For the Yaquis, territory was and is to this day rather more than the countries that comprise it. It has a crucial symbolic dimension that begins with the origin of their possession, which, according to a legend recorded by Spicer (1994), was granted to the Yaquis by angels and prophets, as a result of which they used every means at their disposal to defend it. One of these means was the alliance with notables and/or groups of notables who could help them retain possession of their territory.

The Yaquis, unlike the Ópatas, did not have a military structure recognized by the authorities, whether colonial or national. However, since at the time of Spanish rule, they were compelled, like other Indians grouped together in military aid missions, to provide military assistance for Spanish captains when they required it, the figure of the captain-general18 became the authority around which Yaqui military organization was structured, whose base was its eight traditional villages.19

From about 1846 to 1866, the Yaquis were continuously involved in conflicts that divided the Sonoran notables. As mentioned earlier, the Yaqui-Gándara dyad was regarded by the Sonoran liberals as an obstacle to the progress of the state, as their continuous rebellions against the state government destabilized the state. However, these same transgressions allowed the National Guard, a body of armed citizens at the service of the state government, to serve as a school for training officers who subsequently made a career in the federal army. In short, the National Guard and its constant battles against the Gandarista-Yaquis and Yaquis from 1867 to the first decade of the 20th century, served both to train fighters and to perfect war tactics, which, during the 1910 revolution, helped the Sonora group to occupy the highest positions of power at the national level (Padilla and Trejo, 2012b). From these positions, the Sonorans promoted a national state project, whose origins date from the Yaqui secular war and the Yaquis who, together with the Mayos, actively participated in the revolutionary armies.

Indigenous Citizen

A key aspect of the liberal project is political representation, coupled with the emergence of the modern citizen,20 in other words, an individual citizen with the right to vote and be elected. Among the countries that had recently achieved their independence from the Spanish Crown, one of the main objectives was the dismantling of corporate society, since organization into corps, an essential characteristic of L'Ancien Régime, posed an obstacle to the implementation of measures derived from the liberal project, which would converge into the constitution of Latin American nation-states over the years.

Within this homogenizing framework, indigenous groups were the most reluctant to join liberal society and the institutions being created, since the attempts to dismantle their community organization not only jeopardized the corporate ownership of their land, an aspect that has been highlighted in historiography21 but meant that they risked losing their indigenous self,22 which enabled them to identify themselves as such in the eyes of others, whether these others belonged to white/mestizo society or to other indigenous groups.

In Sonora, researchers have only just begun to explore the reaction of ethnic groups to the liberal project. Research conducted to date has focused on two aspects: their participation in electoral process and the opposition to or acceptance of the liberal laws affecting their lifestyle. In this respect, the most widely documented aspect is the participation of the Ópatas as citizens in 19th century Sonora. On the other indigenous groups, there is no specific work to address this issue, although there is some scattered evidence in the sources. In the case of the Yaquis, they are known to have participated in the electoral processes of the early and mid-1850s. So far, no documentation has been found on the Mayos mentioning their participation in elections or occupying a government position, apart from those they held in their own towns. Regarding the Pimas, given their subjection to the Ópata authorities, at least since the early 1840s, it is extremely difficult to determine the extent to which did or did not share the Ópatas' position regarding the liberal laws that affected them.

José M. Medina Bustos has documented the participation of the Ópatas in their shift from Indians to citizens. One of these studies concerns the enactment of the 89 Law, which decreed the distribution of individual plots of land in the villages inhabited by these indigenous peoples (Medina, 2009 and 2010). Contrary to what one might expect, not all Ópatas opposed the division of their lands, or being regarded as citizens. A survey ordered by the incumbent governor of the Ópata peoples revealed the divisions between them, because while some of them agreed to be considered citizens, others refused and requested to be allowed to continue governing themselves according to their traditional laws.

Citizenship involved the loss of privileges for Ópata society, but also guaranteed them the possession of their lands, since as citizens, they were not only entitled to demand the provision of lands that would enable them to support their families but also to request the measurement and provision of property deeds for the ejidos in their towns. What did the Ópata gain or preserve from refusing to be citizens? On the basis of studies currently being undertaken on this issues, the advantage for the Ópatas of refusing citizenship was that it enabled them to preserve their indigenous self (Trejo, 2010).

When they became citizens, the Ópatas were assimilated into the emerging liberal society. Being citizens implied that they would not only have to accept the laws that favored them but all those passed by local and national governments, regardless of whether or not they respected their political, military and religious traditions. Members of the ethnic group who chose to be regarded as citizens make a small contribution to the process of constructing the Mexican nation-state, since they complied with one of the most important liberal precepts, joining the rest of society and abandoning several features of L'Ancien Régime, such as communal land possession, privileges such as tax exemption and special authorities, among others.

According to the historiography of the Ópatas, they were, of all the Sonoran ethnic groups, the ones that was most quickly assimilated into white-mestizo society by adopting their language, customs and political organization. Medina Bustos' work shows that some of the Ópatas participated in elections, comprised the town halls that governed their towns which were no longer exclusively theirs, since they shared them with whites and mestizos, and accepted the distribution of individual plots of land, in other words, they became citizens. At the same time, the work of Trejo Contreras shows that another group of Ópatas continued to preserve their traditional authorities, captains generals and governors, formed an alliance with the opponents of liberal governments, maintained their military structure and demanded respect for their customs in the political and fiscal spheres, in other words, they did everything possible to remain outside the homogenizing liberal process that sought to insert them in an incipient nation-state, into which they ended up being dissolved in the mid-1870s, eventually disappearing in the early 20th century.

The Yaquis' peaceful participation in the 19th century political scene has not been studied. Researchers' interest regarding this group has focused on their long struggle of resistance, which has been understood exclusively as an armed struggle. There is therefore no research regarding their participation in processes such as elections, although some indications in this regard have been found in primary sources. Because of their military triumphs and partnership with powerful groups of notables such as the Gandaristas, the Yaquis prevented liberal institutions such as constitutional town halls, tax payment and their integration into the Sonoran national guard from being established in their territory. Until the peaceful facet of Yaqui participation in the 19th century Sonoran political sphere is studied, their participation in this and therefore in the construction of the Mexican nation-state, will have to be seen from a military perspective, analyzed in the section on the war axis.

CONCLUSIONS

Describing and analyzing the participation of indigenous groups in the construction of national states is a challenge that undermines the work of writing history, not only because it involves focusing on actors who occupy a secondary position in historical narratives, but also because the traces left by their participation in this long, contentious process are largely indirect. In other words, historians have to read about indigenous people's reaction to everything involving the construction of national states through the testimony of others, namely whites.

This article focuses on analyzing how Sonoran ethnicities participated in the construction of the nation-state, for which three areas were chosen to observe this participation: land, war, and citizenship. Analysis of these aspects shows that the participation of Sonoran Indians in a process that was imposed in the same way as Spanish domination, was composed of a series of responses to specific measures affecting their indigenous self in one way or another.

It has also been pointed out that not all Sonoran Indians responded in the same way to the same measures. Even within the same ethnic group, the reaction to certain laws was not unanimous as evinced in the case of the Ópatas. At the same time, this initial approach to indigenous groups' participation in the construction of the nation-state raises a number of doubts but one thing is certain: Sonoran historiography has a long way to go towards understanding how the ethnic groups settled in Sonora participated in this process, since their behavior was as complex, diverse and difficult to grasp as that of white society.

REFERENCES

Archivo General del Estado de Sonora (AGES), 1846, Hermosillo, Sonora, Fondo Ejecutivo, vol. 160. [ Links ]

----------, 1848a, "Carta de Juan José Armenta a Manuel María Gándara", Hermosillo, Sonora, Fondo Ejecutivo, vol. 199, February 2. [ Links ]

----------, 1848b, "Instancia de los indígenas de Yécora al gobernado Manuel María Gándara", Hermosillo, Sonora, Fondo Ejecutivo, vol. 199, February 18. [ Links ]

Aguilar Zeleny, Alejandro et al., 2009, Caminando por la Pimería Baja. O'ob pajlobguin. Territorio e identidad, Hermosillo, Gobierno del Estado de Sonora. [ Links ]

Borrero Silva, María del Valle, 2009, "Los indígenas y su participación como soldados aliados y auxiliares en la provincia de Sonora en el siglo XVIII", in Raquel Padilla Ramos, coord., Conflicto y armonía. Etnias y poder civil, militar y religioso en Sonora, Hermosillo, INAH/Conaculta. [ Links ]

Carmagnani, Marcello, coord., 1996, Federalismos latinoamericanos: México/ Brasil/Argentina, México, Fondo de Cultura Económica/El Colegio de México. [ Links ]

Castoriadis, Cornelius, 1997, "El imaginario social instituyente", Zona erógena, Buenos Aires, no. 35. [ Links ]

Connaughton, Brian, coord., 2003, Poder y legitimidad en México en el siglo XIX, México, UAM/Conacyt/Miguel Ángel Porrúa. [ Links ]

Constant, Bejamin, 2000, Principios de política, México, Gernika. [ Links ]

Français, Ariel, 2000, "El crepúsculo del Estado-nación. Una interpretación histórica en el contexto de la globalización", Documentos de debate, UNESCO, no. 47, available at <http://www.unesco.org/most/ffrancais.htm>, last accesed on January 19, 2013. [ Links ]

Galeana, Patricia, comp., 1999, La definición del Estado mexicano, 1857-1867, México, Archivo General de la Nación. [ Links ]

García Wikit, Santos, 2003, Nación Yaki, Ciudad Obregón, Impresiones Morales. [ Links ]

González, Luis, 2000, "El liberalismo triunfante", in Daniel Cossío Villegas et al., Historia General del México, México, El Colegio de México. [ Links ]

Hale, Charles, 1978, El liberalismo mexicano en la época de Mora. 1821-1853, México, Siglo XXI Editores. [ Links ]

----------, 2002, La transformación del liberalismo en México a fines del siglo XIX, México, Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Márquez, Esaú; Rafael Araujo, and Rocío Ortiz, coords., 2011, Estado-Nación en México: Independencia y Revolución, Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas. [ Links ]

Medina Bustos, José Marcos, 2010, "¿'Hijos del pueblo' o 'vecinos'? La representación política de antiguo régimen en los pueblos mixtos de Sonora, 1767-1810", Humanitas, vol. 4, no. 37, pp. 275-299. [ Links ]

----------, 2009, "De las elecciones a la rebelión. Respuestas de los indígenas de Sonora al liberalismo, 1812-1836", en Memorias del 53 Congreso Internacional de Americanistas, México, Universidad Iberoamericana. [ Links ]

Menegus, Margarita, 2006, Los indios en la historia de México, México, CIDE/ Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Moctezuma Zamarrón, José Luis and Hugo López Aceves, 2007, Mayos, México, CDI. [ Links ]

Moreno, Heriberto, 1994, "Compradores y vendedores de tierras. Ranchos y haciendas en El Bajío michoacano guanajuatense, 1830-1910", in Beatriz Rojas, coord., El poder y el dinero. Grupos y regiones mexicanos en el siglo XIX, México, Instituto de Investigaciones Dr. José María Luis Mora. [ Links ]

O'Gorman, Edmundo, 1986, La supervivencia política novo-hispana: Monarquía o República, México, Universidad Iberoamericana. [ Links ]

Oliver Sánchez, Lilia, coord., 2006, Convergencias y divergencias: México y Perú, siglos XVI-XIX, México, Universidad de Guadalajara/El Colegio de Michoacán. [ Links ]

Padilla Ramos, Raquel, 2006, Progreso y libertad. Los yaquis en la víspera de la repatriación, Hermosillo, Instituto Sonorense de Cultura. [ Links ]

---------- and Emanuel Meraz Yepiz [paper] 2011, "Revisitando la rebeldía ópata, 1819-1820", Seminar on "Nuevas miradas sobre los ópatas", Hermosillo, Sonora, Centro INAH/Universidad de Sonora. [ Links ]

---------- and Zulema Trejo Contreras, 2012a, "Guerra secular del Yaqui y significaciones imaginario sociales", Historia Mexicana, vol. 62, no. 1, pp. 59-103. [ Links ]

---------- and Zulema Trejo Contreras [paper] 2012b, "Tierra y Paz. Yaquis y ópatas en el triunvirato", International Seminar on "La reelaboración de los arreglos institucionales sobre los recursos naturales, 1890-1940. Proyectos nacionales y recomposición de los poderes locales", San Luis Potosí, El Colegio de San Luis/CIESAS. [ Links ]

Radding, Cynthia, 2005, Paisajes de poder e identidad: fronteras imperiales en el (desierto de Sonora y bosques de la Amazonia, México, CIESAS/El Colegio de Sonora/Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana. [ Links ]

----------, 1995, Entre el desierto y la sierra. Las naciones o'odham y tegüima de Sonora, 1530-1840, México, CIESAS/INI. [ Links ]

Revilla Celaya, Iván Arturo [paper] 2009, "Entre utopías y la ambición por la tierra", II Coloquio de Historia Regional, Hermosillo, Sonora, Department of History and Anthropology, Universidad de Sonora. [ Links ]

---------- [thesis in social sciences] 2012, Liberalismo, utopías y colonización: los valles del Yaqui y Mayo, 1853-1867, El Colegio de Sonora. [ Links ]

Reina Aoyama, Leticia, 2010, Los movimientos indígenas y campesinos, México, Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Reyes Heroles, 1974, El liberalismo mexicano, México, Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Rivera Carbó, Eulalia; Héctor Mendoza Vargas, and Pere Sunyer Martín, coords., 2007, La integración del territorio en una idea de Estado. México y Brasil, 1821-1946, México, Instituto de Geografía-UNAM/Instituto de Investigaciones Dr. José María Luis Mora. [ Links ]

Ruibal Corella, Juan Antonio, coord., 1985, Historia General de Sonora, vol. III, Hermosillo, gobierno del estado de Sonora. [ Links ]

Ruiz Medrano, Ethelia; Claudio Barrera Gutiérrez, and Florencio Barrera Gutiérrez, 2012, La lucha por la tierra. Los títulos primordiales y los pueblos indios en México, siglos XIX y XX, México, Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Sabato, Hilda, coord., 1999, Ciudadanía política y formación de las naciones. Perspectivas históricas de América Latina, México, Fondo de Cultura Económica/ El Colegio de México. [ Links ]

Spicer, Edward, 1994, Los yaquis: historia de una cultura, México, UNAM. [ Links ]

Trejo Contreras, Zulema, 2011, "Aliados incómodos: indígenas y notables en la construcción del Estado-nación. El caso de Sonora (1831-1876)", in Esaú Márquez, Rafael Araujo, and Rocío Ortiz, coords., Estado-Nación en México: Independencia y Revolución, Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas. [ Links ]

----------, 2010, "La preservación del ser: nación y territorio en la re-creación de las sociedades yaqui y ópata frente a la institución de la sociedad liberal, 1831-1876", in Esperanza Donjuan, Dora Elvia Enríquez, Raquel Padilla, and Zulema Trejo, coords., Religión, nación y territorio en los imaginarios sociales indígenas de Sonora, 1767-1940, Hermosillo, El Colegio de Sonora/Universidad de Sonora. [ Links ]

----------, 2008, "Las haciendas sonorenses a mediados del siglo XIX", in Memoria del congreso "Haciendas en la Nueva España y el México republicano, 1521-1940. Viejos y nuevos paradigmas", Zamora, El Colegio de Michoacán. [ Links ]

Velasco, José Francisco, 1985, Noticias estadísticas de Sonora (1850), Hermosillo, Gobierno del Estado de Sonora. [ Links ]

Villa, Eduardo, 1984, Historia del estado de Sonora, Hermosillo, gobierno del estado de Sonora. [ Links ]

Villalpando Canchola, Elisa, 1996, "Sociedades indígenas del contacto", in Historia general de Sonora, vol. 1, Hermosillo, gobierno del estado de Sonora. [ Links ]

Yetman, David, 2010, The Ópatas. In search of a Sonoran people, Tucson, The University of Arizona Press. [ Links ]

1 Thie concept of nation-state is a neologism that emerged from the political sciences at the base of which lie two key concepts in 19th century political history: state and nation. There is an extensive literature in both history and political science on the definition of both concepts and the concept resulting from their union, in other words, the nation-state. One of the most striking works in this bibliography is "El crepúsculo del Estado-nación. Una interpretación histórica en el contexto de la globalización", by Ariel Franfais (2000), which provides a successful synthesis of the emergence and development of this neologism.

2 It should be pointed out that traditional political history studied the process of nation-state formation from an apologetic perspective, highlighting the role of the great military heroes and/or statesmen who excelled in the development of this process. This perspective, valid at the time since these were the first studies conducted on this issue, excluded not only other actors such as indigenous groups, African-Americans and women from their research, but also other issues such as electoral processes, the fiscal, economic, legal and cultural sphere of the time, and everyday life.

3 It should be pointed out that the versions cited of these works are not first, but rather second and third editions, meaning that publication dates do not coincide with the time referred to in this paper.

4 "Carta de Juan José Armenta a Manuel María Gándara", in Archivo General del Estado de Sonora (henceforth referred to as ages, 1848).

5 In the case of Sonora, there is Law 89, from the 1820s (Colección de los decretos expedidos por el Honorable Congreso Constituyente del Estado Libre de Occidente, desde 12 de septiembre de 1824 en que se instaló, hasta 31 de octubre de 1825 en que cerró sus sesiones, s/l, Imprenta del gobierno del estado de occidente, undated), and decree 16, issued in 1847 (see "Instancia de los indígenas de Yécora al gobernado Manuel María Gándara", February 18 1848, in AGES, fondo Ejecutivo, vol. 199, yr. 1848). The two legislative pieces affected the ownership of indigenous societies and at least until 1876, were constantly cited by Opata and Pimas requesting the Sonoran authorities to comply with them. Nationwide, authors such as Ethelia Ruiz, Claudio Barrera and Florencio Barrera (2012) together with Margarita Menegus (2006), have documented the role of land ownership in the history of indigenous groups.

6 The author speaks of the indigenous sef from the perspective of the social imaginaries proposed by philosopher Cornelius Castoriadis, who regards the self as the socialized self (Castoriadis, 1997).

7 Works such as Progreso y libertad: los yaquis en la víspera de la repatriación, by Raquel Padilla Ramos (2006); The Ópatas. In search of a Sonoran people, by David A. Yetman (2010); Paisajes de poder e identidad: fronteras imperiales en el desierto de Sonora y bosques de la Amazonia, by Cynthia Radding (2005); and Caminando por la Pimería Baja. Oob pajlobguin. Territorio e identidad, a work by Alejandro Aguilar Zeleny et al. (2009), form part of the new historiography about the indigenous groups that inhabit or inhabited Sonora.

8 Ignacio Pesqueira of Sonora ruled 1856-1875; traditional historiography regards him as the liberal hero of the state.

9 Several authors have studied this conflict in the Yaqui, from classic authors such as Troncoso, Balbás, Ocaranza, to contemporary authors such as Edward Spicer, Evelyn Hu-Dehart, Raquel Padilla, and Zulema Trejo.

10 Some notes on the subject are available in Mayos, by Moctezuma and López (2007).

11 This can be seen in the section on the sale and allocation of vacant land that is part of the 1857 report on development, colonization and trade.

12 In a recent study, Padilla and Meraz (2011) argue that although the apparent cause of the Ópata rebellion of the 1820s, was the abuse Ópatas soldiers received in prisons, its root cause was the Ópatas' defense of their land.

13 At least since the early 1840s, Ópatas and Pimas seem to have merged into a single nation, led by a captain general of Ópatas and Pimas. At the same time, it is not exactly known which towns were inhabited by these two ethnic groups.

14 The documents reviewed to date suggest that Gándara did have the consent of the Yaqui leaders for his colonizing project.

15 Members of the Gandarista faction were mostly owners of farms and ranches, properties which thanks to the 1830 "Law of servants" were granted certain rights over the workers who inhabited their rural estates, governed like a corporation whose economic autonomy was based on the cultivation of land.

16 Current Sonoran historiography is in the process of dispelling the myth of an exceptional Sonora, with little or no contact with national events until before the 1910 revolution. In this respect, similar events to those that occurred in this area have begun to be incorporated into the historical analyses of 19th century Sonora, such as attacks by Apache groups, a phenomenon shared by virtually all the territories on the northern border. Intermittent warfare with indigenous groups was not exclusive Sonora, as evinced by the war in Yucatán and indigenous rebellions in the Sierra de Puebla.

17 Some authors, including Edward H. Spicer, place the beginning of the Yaqui secular war in 1740, when the first Yaqui rebellion took place.

18 This position was created within the Jesuit missions located in the territory now occupied by Sonora, and was intended to recruit and manage the indigenous troops that left the mission to assist the Spaniards.

19 The eight traditional Yaqui villages, which exist to this day, were founded as Jesuit missions in the 17th century.

20 In the Old Regime, there were also citizens, except that the term was strictly applied to the residents of a city who could enjoy the rights and privileges granted to it in the title through which the king granted it the status of city.

21 There are a wide variety of articles and books devoted specifically to this topic, the most recent being named Leticia Reina (2010) and Ethelia Ruiz, Claudio Barrera and Florencio Barrera (2012).

22 Those who study indigenous groups use the word indigenous identity rather than indigenous self to refer to the elements that enable ethnic groups to recognize themselves and others as indigenous groups. The author of this paper prefers to use the term self derived from the social imaginary approach proposed by Cornelius Castoriadis in the 1960s. The indigenous self covers symbolic, tangible elements that shape social-imaginary meanings which, when re-created, are embodied in institutions that characterize the groups, in this case indigenous people, of these social groups.