Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Estudios fronterizos

versión On-line ISSN 2395-9134versión impresa ISSN 0187-6961

Estud. front vol.18 no.37 Mexicali sep./dic. 2017

https://doi.org/10.21670/ref.2017.37.a07

Articles

The effects of DACA in young migrant´s professional careers and emotions

a Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social, Mexico City, Mexico, e-mail: mbarros55@hotmail.mx

Tuesday 5 of September of 2017 President Trump announced the end of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and gave Congress six months to find a solution for the lives of these young people in the US. The present article has the objective to study the effects that DACA has had on the professional careers of young migrants and their emotions through four field work stays between 2012 and 2016 in the agricultural valley of Santa Maria, California, open interviews were implemented to young women and men, following the transformations in their studies, work and emotions. The data obtained is qualitative. In the study, we can see how the young made an effort to continue their studies and search for employment outside the rural sector. Their emotions went from fear and lack of hope to feelings of hope. However, fear has come back again to their lives.

Keywords: DACA; young migrants; professional career and emotions; California; United States

El martes 5 de septiembre de 2017 el Presidente Trump, anunció el fin del programa Acción Diferida para la Deportación de Menores (DACA) y le dio al Congreso seis meses para encontrar una salida para la vida de estos jóvenes en E.U.A. El presente artículo tiene como objetivo estudiar los efectos que el DACA ha tenido en las carreras profesionales y en las emociones de los jóvenes migrantes, a través de cuatro estancias de trabajo de campo entre 2012 y 2016 en el Valle Agrícola de Santa María, California, donde se llevaron a cabo entrevistas abiertas a jóvenes, siguiendo las transformaciones de sus estudios, trabajos y el desarrollo de sus emociones. Los datos obtenidos son cualitativos. En el estudio vimos como los jóvenes se esforzaron por continuar sus estudios y buscar empleos fuera del sector agrícola. Sus emociones pasaron del miedo y la desesperanza a sentimientos de esperanza. Sin embargo, una vez más el miedo regresó a sus vidas.

Palabras clave: DACA; jóvenes migrantes; carrera profesional y emociones; California; Estados Unidos

Introduction

This article examines the lives of young people who arrived in the United States with their families as children and grew up there, attending elementary schools and often completing high school. Some were able to enter community colleges, others universities. They grew up believing they would spend the rest of their lives in the United States, for their dreams and expectations were built there; however, they were constantly faced with the harshness of undocumented life. From a young age, some of them experienced the deportation of their parents, the profound sadness of their absence and the constant fear of losing another; others faced bullying in school, where they were singled out and stigmatized for being undocumented. They were forced to confront their condition more directly upon finishing high school and attempting to enter community college or university, only to see their paths continually blocked by obstacles and challenges their friends and even siblings with citizenship did not have to face, or upon attempting to find a good job and being unable to do so for lack of papers proving residency or citizenship.

In 2012, thanks to organizing and pressure by thousands of young people known as dreamers,1 President Barack Obama signed the DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) executive order, which gave undocumented young people permission to study and work. However, the program did not provide a definitive solution to the problem but rather only a temporary solution in the form of a renewable two-year permission subject to presidential discretion that could be revoked at any time, as occurred on September 5, 2017, when Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced on behalf of President Trump that the DACA program would be terminated.

During his campaign, current U.S. President Donald Trump expressed his intention to cancel all executive orders signed by President Obama. In a press conference on February 16, 2017, he said there would be a solution for DACA recipients but that this group of young people included gang members and hence they would have to face justice. Two days earlier, on February 14, a young DACA recipient was arrested by ICE2 to be deported (Levine & Cooke, 2017). President Trump remained ambivalent about DACA for several months, but 10 state attorneys general threatened to sue him if he did not terminate the program by September 5th (Dinan, 2017), and thus, he decided to fulfill his campaign promise to end it. His proposal gives Congress six months to find a solution for DACA recipients, but it should be recalled that President Obama had to resort to an executive order due to Congress’ inability to pass any type of measure to help undocumented youth.3 This decision places approximately 800 000 young people and their families once again in a situation of fear and anxiety, with an uncertain future.

In this scenario, the future of young DACA recipients remains in the hands of members of Congress and their supporters. The coming months will consist of a series of struggles in the streets, over the phone, and through letter writing campaigns to representatives, all existing tools will have to be utilized to support these young people and mobilize legislators. Meanwhile, young people are experiencing fear and uncertainty, and this uncertainty is having a negative impact on them and their families.

It is important to note how DACA has affected these young men and women, and thus, this article presents the changes that have occurred in the lives of DACA recipients between 2012 and 2016, both at the professional level as well as in their emotional lives, with the objective of understanding the impact of this program on their lives and daily realities.

By the end of 2016, there were just over 752 000 young people enrolled in the DACA program (Mathema, 2017). The state with the largest number of DACA recipients was California, with 216 060, followed by Texas, with 120 642, and North Carolina, with 26 936. It is estimated that 80% of them were working, and the rest were studying (Mathema, 2017). In recent months, in the area under study -the agricultural valley of Santa Maria, California- renewals of DACA permissions stopped almost entirely. Following the presidential election, activist organizations recommended that nobody take steps to register until it was clear what action would be taken by President Trump, who for months expressed his intention to terminate DACA upon entering the White House. Now, he has delivered on those threats.

DACA recipients are faced with a state that is increasingly hardening its policies toward undocumented immigrants, whom it has criminalized for decades, taking this way of regulating immigration to the extreme, such that the lives of undocumented immigrants and their families are increasingly difficult, precarious and violent (De Genova, 2002; Dowling & Inda, 2013). This situation worsened during presidential campaigning due to the “Trump effect,” with the candidate openly insulting and expressing racist attitudes toward the Mexican population and causing others to follow his example (Barros, 2017). Even eight months after taking office, Trump continued to demonstrate his racist side, such as his refusal recently to take a firm stance against the white supremacist groups that marched in Charlottesville, Virginia, on August 12, killing one woman (Merica, 2017). This ambivalence toward racist acts and groups affects all immigrant communities, as xenophobic sentiments against them emerge with greater frequency and force.

Young DACA beneficiaries arrived in the United States as children or adolescents and were integrated into the U.S. educational system, some more successfully than others, joining the school system and achieving community college and university level education. However, their path has not been an easy one, and many were challenged by multiple obstacles during their high school careers that led them to fail to receive their diploma or not take the courses they wanted because they were undocumented. These children are becoming adults, and their future largely depends on their legal situation in the United States.

In this article, we present some of the effects DACA has had on the lives of young people in the agricultural valley of Santa Maria on California’s central coast who are members of families with mixed legal status, meaning that some members may have citizenship, while others are residents or have work permits, and still others are undocumented. The majority of their parents came to the valley to work in agricultural jobs, whether as day laborers or in the freezers or nurseries. Some have been able to leave the fields and find work in construction, especially during boom times in that industry, as well as in services and commerce, although the great majority work in the fields (Barros, 2015a).

This article is based on information gathered during four fieldwork visits, each lasting six weeks, between 2012 and 2016. During these years, I had the opportunity to interview 11 young people between 18 and 30 years of age about DACA and the effect it was having on their lives. The group includes five women and six men who ranged from 4 to 11 years of age upon arriving in the United States with their families. All are mestizos, hailing from different parts of Mexico, and all of them applied and were admitted to the DACA program. In addition to this group, I interviewed another 25 young people, 25% of whom did not apply for DACA, either because they did not qualify or because they chose not to do so yet. Three were married and had children. I interviewed them on several occasions: once when they were approved for DACA and once or twice subsequently over the course of the four years from 2013 to 2016. I used the snowball method to locate interviewees, with one individual leading to the next. I also approached organizations that were helping young people fill out applications, and they asked applicants if they would be willing to be interviewed by me; if so, they arranged an interview.

The interviews were open-ended, and questions focused on how interviewees’ lives had changed since they were granted DACA status and the characteristics of those changes. In their responses, interviewees primarily mentioned two aspects of their lives that were affected since entering the program. The first area is what is referred to in this article as professional career, which includes all activities carried out as part of education and work that contributed to improving their current economic level and expectations for the future. The second area involves emotions. Interviewees described how their fear of being discovered as undocumented and deported to an unfamiliar country disappeared once they gained DACA status. This caused changes in other emotions and in relationships with family, friends and the community as well as in their perception of their future in the United States. However, as the Trump campaign began to strengthen and eventually won the presidency, uncertainty and fear returned to their lives.

This article is divided into two sections. In the first part, interviewees describe the effects DACA has had on their professional careers, expressing interest in continuing their studies in order to improve their employment opportunities in the short term and obtain better jobs once their legal situation is resolved. In the second part, subjective aspects are analyzed, specifically how DACA has influenced the emotions of these young men and women, concentrating on their emotions of fear, disappointment, despair and hope and paying special attention to how the effects of DACA differ between men and women.4

Violence against undocumented immigrants has increased in recent decades. The majority of interviewees arrived in the United States when they were small and did not realize that they were undocumented until much later, sometimes not until their last year of high school, at which point they had to make decisions about their future and saw their options limited due to their immigration status; however, being members of families with mixed immigration status, from a young age, they felt the pressure and fear experienced daily by their undocumented family members, and some even experienced the deportation of loved ones. They were subjected to the government’s disciplinary procedures against undocumented immigrants, such as biometric technologies, criminalization based on the legal framework, restrictions on the use of public services, and the fear of being arrested at any moment, even in their own homes upon waking up, possible incarceration and subsequent deportation, and constant fear of being deported at any moment (Aquino, 2015; Barros, 2017).

The Context: The Agricultural Valley of Santa Maria, the Dreamer Movement and DACA

Since the beginning of the last century, a constant flow of immigrants has arrived in the Santa Maria Valley. In 1942, the Bracero Program began, and with it, trucks full of workers arrived each year at the beginning of the agricultural cycle in the valley along with undocumented workers in search of work who lived in camps for agricultural day laborers located in rural areas.

In the 1950s, the valley experienced a major agroindustrial boom, and a number of agroindustries were created, including flower and vegetable greenhouses, fertilizer plants, box manufacturers, packinghouses, etc. Some braceros and ex-braceros began to live on the edges of towns, renting rooms, and some Mexicans were able to establish businesses to serve the growing Mexican population (Barros, 2009).

In 1964, the end of the Bracero Program marked the beginning of constant and growing settlement by Mexicans. Discrimination against Mexicans was very strong, and only a few families ventured to open businesses or buy homes. However, important changes were occurring among the Mexican population, notably the movement of César Chávez, which would have a very large impact on the economic and political lives of agricultural day laborers and on the lives of Mexican immigrants in general. This would constitute the beginning of the rise of consciousness regarding the possibilities and rights of agricultural workers as employees and as citizens in the United States, which would be reflected in their interest in their city.

The main economic activity in the valley was and continues to be agriculture and related agroindustry. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, agriculture underwent a series of changes, and fruit and vegetables began to be produced on a massive scale in the valley, which required more manpower. An increased use of technology also lengthened the harvests, and wages rose. This increase in job availability during the year gave agricultural workers the possibility of staying for longer periods and establishing themselves in the United States, which, along with higher wages, drew populations from various states in Mexico to California for jobs in farming and agroindustry.

The amnesty in 1986 (Immigration Reform and Control Act or IRCA) enabled many immigrants to obtain residency and eventually citizenship. With the family reunification program, many families were reassembled. More recently, however, the growing militarization of the border has made it ever more difficult, dangerous and costly for workers to go back and forth, leading them to stay for increasingly longer periods.

These workers, who hail from different states in Mexico, particularly Jalisco, Irapuato, Zacatecas and Oaxaca, are inserted in one of the most productive agricultural regions in the world, joining this capitalist agricultural economy gradually over the decades, even when work in the fields is poorly paid and carried out in grueling conditions amid insecticides and pesticides detrimental to their health.

Families thus migrated with their small children, settling in the valley. Many of them also had children in the United States. Thus, older children arrived when they were small and grew up the United States, feeling as though they were part of U.S. society despite being undocumented, while younger children were born in the United States with U.S. citizenship.

The economic crisis began to be felt in the mid-2000s. In 2008, a recession was officially declared in the United States, part of a global crisis that affected the entire world. Latinos were among the most affected groups, even before the recession became official. From 2007 to 2009, the unemployment rate among Hispanics born outside the United States increased from 5.1% to 8.0% nationally, and that among U.S.-born Hispanics grew from 6.7% to 9.5%. The general population saw a much smaller rise in unemployment, from 4.6% to 6.6% (Kochhar, 2009).

Employment in the construction sector and all the businesses that supply it peaked in 2007. This was one of the sectors employing the greatest number of Latinos: 54.2% of jobs lost by Latinos were in the construction sector (Kochhar, 2008). By 2008, economic production had fallen to levels lower than in 1930 (Cornelius, FitzGerald, Lewin & Muse-Orlinoff, 2010), and Latinos were losing their jobs faster than any other group in the United States (Kochhar, 2009). In 2010, the total population of California was 37 253 956, of which 30.7% were of Mexican origin. California had a 12% unemployment rate, and 14% of those unemployed were Latinos (United States Census Bureau, 2010). The population of the city of Santa Maria was 99 553, of which 70 114 (70.42%) were of Mexican origin, with an unemployment rate of 5.2% (United States Census Bureau, 2010).

As the United States was facing these problems, a generation of young people were growing up in schools and making efforts to enter community colleges and universities, a generation of young people who struggled to obtain an education and learned strategies to improve their situation and that of their families in the United States. These spaces allowed them to learn about their rights and the possibilities of the struggle to change their situation as undocumented people. Some of the undocumented became activists, deciding that the best strategy was to make their situation known. They contacted senators and representatives to give visibility to thousands of young people like themselves. This was the origin of the dreamer movement, which motivated young people to fight against the criminalization of immigrants and make themselves visible to society and the government (Truax, 2013). The dreamer movement had a varying impact on rural areas. In Santa Maria, there is a small group of dreamers comprised of 10 students from Allan Hancock College who organize various activities to raise money to help undocumented students pay for enrollment and books. However, outside of this circle, few young people knew about the movement even in 2016, and fewer still actively participated in it.

The dreamer movement has brought benefits to young undocumented people in the United States, among the most important of which was to draw the attention of the Obama government and the general public to the situation of this generation that arrived as children and grew up in the United States, called “generation 1.5.” After more than two decades without any amnesty or measures to support immigrants in obtaining residency, the Obama administration put DACA in motion in June of 2012. The measure offered to temporarily protect childhood arrivals from deportation for a period of two years with the possibility of renewal, although it was not a residency permit that could eventually lead to citizenship.

Deferred action on deportation granted young people who met certain criteria the possibility of requesting permission to work for two years, with social security and a driver’s license in some states such as California. However, it was subject to renewal or revocation by Donald Trump. The requirements imposed by this executive order excluded many young people who did not qualify or did not “submit their paperwork” for various reasons including lack of money, lack of confidence in the system, fear that they and their families would be deported once their information was provided, and the belief that it was unfair to exclude their parents from a program designed to provide relief to families in increasingly difficult situations (Barros, 2015b).

Thanks to the struggle of the members of the movement United We Dream, which gave rise to the Dream Act,5 in an action many considered motivated by electoral purposes President Obama presented the “temporary” initiative on Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), which came into effect on August 15, 2012. It was estimated that more than 1.4 million young people matching specific characteristics6 were eligible to join the program and receive a deferral of deportation and permission to work for two years. The measure is geared toward young people who were brought to the United States as children. It is calculated that of this figure, 1.1 million (or 65%) are of Mexican origin, 60 000 are Salvadoran and 50 000 Guatemalan; 57% of DACA beneficiaries reside in California, Texas, Florida, New York and Illinois (“Beneficiarán a más ‘Soñadores,” 2012).

Meanwhile, President Obama is among the presidents with the largest number of deportations on record in contemporary U.S. history, an action that has separated families and left children without their parents, creating a climate of anxiety and marginalization in which children and young people fear that, at any moment, their parents or they themselves, if undocumented, could be arrested and deported by U.S. authorities.7

There is no doubt that DACA was a major step forward that helped thousands of undocumented youths who arrived in the United States as children and live in families with mixed legal status. The growing deportations have affected these families in particular. In 1998, 27% of families with children in California were of mixed legal status (Fix & Zimmermann, 2001, p. 399). In these families, we find children who were born in the United States who are U.S. citizens by birth and children who were brought to the country when they were young and have remained there, undocumented. The possibility that they or their parents would be deported at any moment has caused their lives to unfold in an environment not only of marginalization and discrimination but also fear and growing violence.

In 2012, a total of 152 423 requests for DACA status were accepted, and 5 395 were rejected; in 2013,8 427 601 were accepted and 16 356 rejected; in 2014, 122 444 were accepted and 19 136 rejected. In 2014, renewals began for the first young people to have received DACA, and in that year, 116 441 renewals were accepted and 5 762 were rejected. In 2015, 26 696 first-time requests for DACA status were made and 2 287 were rejected, while 118 550 renewals were granted and 6 886 were rejected. By 2015, a total of 727 164 requests had been accepted and 43 174 rejected, while 234 991 have been renewed (USCIS, 2015).

The Effect of DACA on the Professional Careers of Young People

To analyze how DACA has affected the working lives of young people, we will draw on the concept of career initially developed by Hughes (1960), which was used as an analytical tool to study the sequence of movements from one position to another in an occupational system made by an individual working in that system. Hughes developed a model that takes into account objective external factors, such as the structure of opportunity and existing limitations, as well as subjective factors, such as changes in the perceptions, motivations and desires of each individual (Hughes, 1960).

In the previous section, I presented the context in which young people grew up, which provides an idea of the structure of opportunity that exists in the city in which they live, which is located in an agricultural valley in which the main activity is agriculture and related agroindustry. It is important to mention this context, as all of the parents of the young interviewees, with the exception of two, work either as day laborers in the fields or in agroindustry. All of the parents I spoke to mentioned that they had come to the United States with the dream that their sons or daughters could have a better life than they had had, and they all wanted their children to receive an education and find jobs outside of agriculture, with better working conditions. Carmen comments:

When I finished high school, I only found work in the fields, hard work, tiring, so, I wanted to study and do something else, out of the sun, the insecticides. I saw how my parents suffer in the fields. I don’t want that (Carmen, Santa Maria, 2015).

The young people know how difficult their parents’ employment situation is and want something different for their own lives. Below, we will consider their school situation before DACA and whether DACA allowed them to continue or complete their studies, as well as discuss the jobs they were able to hold before and after DACA.

These young people entered school when they arrived in the United States, but not all finished high school.9 Among those interviewed, only 70% finished high school.

Alfredo states:

I arrived when I was 14; my father put me in school because it’s obligatory here, but he wanted me to work in the fields with him. He needed my help. At school, it was hard for me to learn English, and I didn’t understand what they were doing. I didn’t get my diploma. But when I found out about DACA, I signed up for classes and I’m about to get it. I want to get out of the fields, and DACA is my opportunity (Alfredo, Santa Maria, 2013).

Like Alfredo, when they heard about DACA, many of those who had been unable to obtain their high school diploma enrolled in classes at community colleges and other authorized schools and obtained their certificate of studies.10

However, even when they did finish high school, the majority faced a series of obstacles to continuing their studies due to their undocumented status, mainly paying high tuition, purchasing expensive books, and being unable to compete for the same financial support as those with legal status. Some did so without documents. Felicia states:

In college, they didn’t let me take the computing class because it was more expensive for the undocumented; so, it was only for those with papers. I could only take the class when I got DACA (Felicia, Santa Maria, 2015).

These young people lost the hope of pursuing the professional careers they thought they could have when they were adolescents. For example, Felipe states:

I wanted to study to be a nurse, you know, I have always really liked medicine and helping people. So, without documents it was not worth it, as they wouldn’t hire me anywhere. So, I continued my studies, you know, and started working as a waiter. When I got my DACA, right away I started studying, and now I’m doing my internship. I’m very happy, I am doing my dreams, finally, thank you Obama!! (Felipe, Santa Maria, 2012).

Felipe was able to escape low-paying work that did not help him achieve his dream: to do what he was most drawn to, helping people, studying nursing. Without DACA, he would not have been able to have this career, which is currently in high demand in the United States. As in the case of Felipe, another two young DACA beneficiaries interviewed were studying nursing, a career in which there are employment opportunities in the region for those aspiring to earn a good salary.

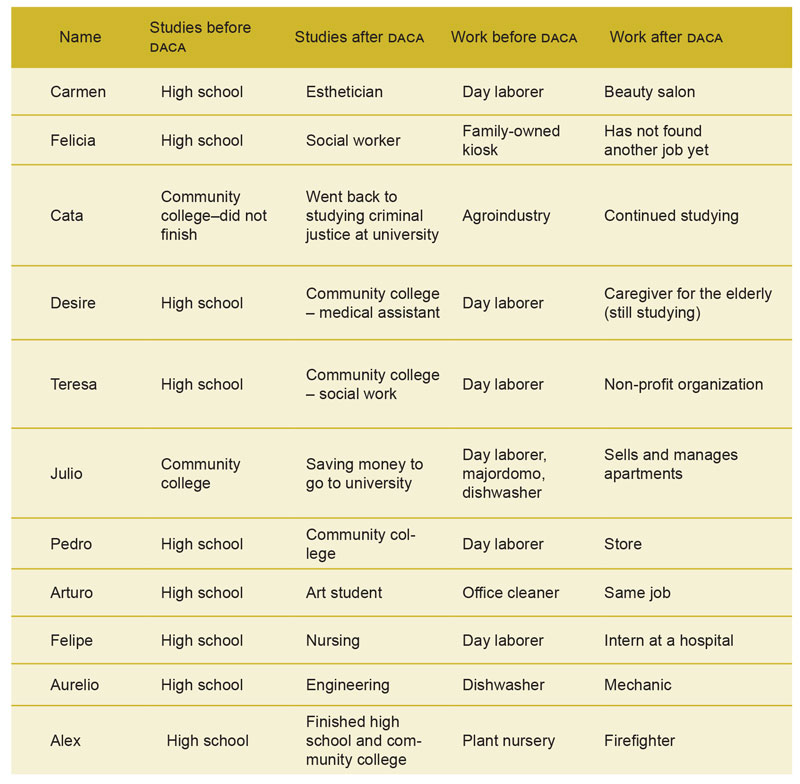

In Table 1, which shows the changes the young interviewees have experienced in their careers, we can see that prior to DACA none had finished their studies at community college, and one had not finished high school. Now, they are all studying subjects they are interested in, which allows them not only to have better jobs and be more productive members of society but also to live happier lives and feel that they are doing something they enjoy, as Felipe explained above. For her part, Carmen (2014) states: “Thanks to DACA, I am doing something I like, I am happy, you know.” The majority found new and better-paying jobs after receiving DACA.

As we can see, DACA has helped these young people to develop a professional career that allows them to have a different future outside of the agricultural work that has kept their parents in situations of poverty and constant precariousness and also deeply affected their health. DACA gives young people permission to work, and in California, before the state approved driver’s licenses for all undocumented people in January of 2014, young DACA recipients could apply for a license. They could also continue studying and access financial assistance for their studies, something they could not obtain without papers. Gerardo states:

Before DACA, I thought I would work in the fields my whole life like my father. So, in high school I had lots of dreams, and then I realized my situation, and it was a great disappointment. But my life changed with DACA! (Gerardo, Santa Maria, 2015).

DACA and Young Peoples’ Emotions

These young people grow up in a scenario in which immigration is regulated through criminality and immigrants are kept in a situation of fear and terror of being deported at any moment so that their labor can be exploited and capital may do whatever it wants with them. They believe that they are Americans just like their younger siblings, friends and peers in school, and then they gradually realize that they are different, that they do not have rights, that their futures are different. Fear begins to enter their lives. For some, it is gradual, and for others, it arises from one day to the next due to events that mark them, such as the sudden deportation of a parent that leads them to realize that their life will no longer be the way they dreamed it would be. Ana states:

Years ago, when I was a girl, I was still sleeping when I heard a knock on the door, hard, we all woke up and my mom put me under the bed with my brother. She told me, “Don’t come out.” After a long while, we came out, my mom was crying, la migra had taken my father away. I felt a deep pain, hard, in my stomach, I felt fear. It didn’t leave me for years. I thought… will I be next? That feeling of fear was taken away from me when they gave me my DACA. Finally, that pain left (Ana, Santa Maria, 2013).

Emotions do not occur in an individual vacuum. They arise among individuals and groups of individuals. In his writings, Le Breton (2012) states that emotions:

Are relations and hence are the product of a social and cultural construction and are expressed in a set of signs that man always has the possibility to deploy, even if they do not feel them. Emotion is at once interpretation, expression, signification, relation, regulation of an exchange; it is modified according to the audience, the context, is differentiated in its intensity, and even in its manifestations, according to each person’s singularity (Le Breton, 2012, p. 69).

Feelings are thus relational (Bericat, 2012; Le Breton, 2012) and develop according to the relationships we have with others.

The definition by Besserer (2000) is very useful in understanding the case of these young people. The author makes a direct connection between forms of governing and emotional norms, introducing resignation of power into the study of emotions. He argues that each form of governance establishes emotional rules according to the socio-political context. In the cases I present, the U.S. government imposes feelings of fear and terror. This is clearly evidenced in the stories told by interviewees and the way in which the growing criminalization of immigrants and governance through deportation, making them “deportable” subjects, creates sentiments of fear that influence and impact their lives and their relationships over time with family members, school peers, teachers and other city residents.

The fear these young men and women feel in their daily lives is manifested in various ways. The state imposes a reign of terror over those it considers illegal; nevertheless, it relies on them for the system to continue functioning. In the jobs they are able to obtain, undocumented young people are forced to accept lower salaries and fewer benefits and are prevented from demanding fair contracts and fighting for their human rights, unleashing sentiments of despair and fear

DACA status brought about changes in the emotions of young people. Having a certain security in their legal situation in the United States took away the fear they had been experiencing, and for some years, they were able to feel a sense of calm in their lives. Aurelio states:

I realized I didn’t have papers when I tried to find a job in a company and my dad told me that special papers would be needed for that job, ones I didn’t have. Here, we all know that there are undocumented people in the fields but I never thought I was one of them. In that moment, I felt as though a gray cloud passed over me. Everything I had heard about them, and now it was me. It was a strange feeling. I was sad. But above all, I was afraid… With DACA, I can find the job I want and walk calmly in the street (Aurelio, Santa Maria, 2016).

Another emotion young people mentioned frequently was disappointment - the disappointment they felt upon finishing high school and realizing how difficult their lives would begin to be and that it was because they lacked papers. Among DACA recipients, this feeling disappeared. Alejandro states:

Upon leaving high school, I felt very disappointed in myself, my life, my family. I did not know what to do. I didn’t want to work in the fields, but what other option did I have? Then, I heard about DACA, everyone was afraid, saying, no, you had to give information about your family, it was a trick, but I did it. The moment I received my papers, I felt like a cloud was lifted (Alejandro, Santa Maria, 2013).

Interviewees commented that, upon receiving their papers, they felt as though the dark cloud under which they had been living was lifted and they could once again have hopes, make plans, and dream.

For the majority of interviewees, the decision to apply for DACA was a family one. On one hand, many needed help from their parents to pay the necessary fees. On the other, some family members did not agree with providing information about the family to the authorities, which might later use it to deport the undocumented. Thus, some young people took months to make the decision. Teresa states:

When I told my family I wanted to apply for DACA, at first they said yes, but soon my siblings said no. They arrived older and didn’t qualify. They told me that because of me they would know about the family and la migra would come for everyone. These were very painful discussions. We cried for three months. They asked why did I want to study if I’m a woman and I was going to get married and leave it all (Teresa, Santa Maria, 2014).

Teresa’s case is representative of the situation of many young women who want to study but whose families think that because they are women, their future consists of marriage and having children. Although family members do partly want them to study, finish high school and go to college, when it comes time to make decisions, these arguments continue to be used to keep women in the home. For Teresa, it took three months of crying and fear to convince her family that applying for DACA was the right thing, not just for her education but also for her future in the United States and to avoid deportation.

Life in families with mixed legal status is complicated; in some cases, we find examples of great solidarity, and in others, tensions and jealousy exist among family members, and particularly between children who have papers and those who do not. Children who do have papers blame those who do not for the limitations they place on their lives, such as not being able to travel or take family vacations. Meanwhile, undocumented children feel that they have fewer opportunities and tend to feel sad and depressed because they lack the opportunities of their siblings (Barros, 2015b). Interviewees commented that these emotions tended to change with DACA because they no longer felt the same level of vulnerability and lack of opportunities. Gloria states:

At 15 years old, I got pregnant and had to leave school. I couldn’t believe what was happening to me. I had my daughter by myself, at my Aunt’s house. My dad kicked me out. It wasn’t until after he saw the baby that he let me come back. My sister finished high school and found a good job, and I went to the fields. It was a very hard life and my sister kept making me feel bad. When they told us about DACA, I signed up for classes, I got my degree and I got my credential. I got into college to study criminal justice and now I work in a cooler with a better salary, I get along better with my family, I feel better (Cata, Santa Maria, 2016).

Final Remarks

In this article, we have observed that even in contexts with few economic opportunities, such as agricultural valleys in which the large majority of jobs are for migrant day laborers, young DACA recipients were able to continue their studies, and the majority found work outside of the fields in activities that are more highly paid and more attractive in terms of their personal development.

It is important to highlight the interest these young people have in continuing their studies, for they know that this will provide them with better opportunities in life. However, it should also be noted that the women in our study faced greater challenges than the men, both in continuing their degrees and applying for DACA, facing doubt and questioning by their families. The decision to apply for DACA was difficult for all interviewees, but women faced more questions from family members. Applying for DACA brought doubt and fear to all family members who were afraid the government might later use their information to deport them, but once young people were granted DACA status and had permission to work, important changes occurred in their lives. Knowing that they could no longer be deported and that they had the freedom to choose gave them hope, took away or reduced the fear they experienced, and brought them out of the shadows, allowing them to once again feel part of the country they always thought was their own and to continue building their dreams.

However, the Trump era has generated new uncertainties, terrifying undocumented people in the United States. During his campaign, Trump stated that if he became president, he would cancel the DACA program, which he announced on September 5, 2017, as being achieved. Although he gave Congress six months to find a solution for the lives of these young people, this caused great consternation among the immigrant population. Many young DACA recipients, however, have an education, are familiar with the political life of the United States, and are activists willing to work to secure their future.

Through the examples provided in this article, we have gained knowledge about the life experiences of thousands of young people who arrived as children and grew up in the United States, becoming bilingual and bicultural. They have decided that education is the best way to get ahead and contribute to the society in which they live, and hence we hope that Congress and society in general will value the importance of this generation of women and men to the country’s future and acknowledge the damage that ending DACA would do, not only to them but also to a whole generation of young people who live alongside these families and have U.S. citizenship.

REFERENCES

Aquino, A. (2015). “Porque si llamas al miedo, el miedo te friega”: La ilegalización de los trabajadores migrantes y sus efectos en las subjetividades. Estudios Fronterizos, 16(32), 75-98. [ Links ]

Barros, M. (2009). La calle Guadalupe. En B. M. Valenzuela y M. Calleja (Comps.), Empresarios migrantes mexicanos en Estados Unidos (pp. 211-234). México: Universidad de Guadalajara. [ Links ]

______ (2015a). Apuntes sobre vivienda para migrantes y la crisis inmobiliaria en la California rural. Un estudio de caso. El Cotidiano, (191), 33-43. [ Links ]

______ (2015b). Jóvenes de origen mexicano en los remates del sur del Valle Central de California, E.U. Internacionales. Revista en Ciencias Sociales del Pacífico Mexicano, 1(1), 49-85. [ Links ]

______ (2017). “El Efecto Trump” en niños y jóvenes migrantes en la California Rural. Migración Ichan Tecolotl, 26(304). [ Links ]

Barros, M. y García, E. (2015). Jóvenes mixtecos migrantes de Oaxaca y el DACA. Estudios de caso en el valle de Santa María, California. Revista Con-temporánea, 2(4). Recuperado de http://con-temporanea.inah.gob.mx/node/111 [ Links ]

Beneficiarán a más “Soñadores”. (8 de agosto de 2012). El Universal. Recuperado de http://www.eluniversal.com.mx/internacional/78921.html [ Links ]

Bericat, E. (2012). Emotions. Sociopedia. ISA. doi:10.1177/205684601361 [ Links ]

Besserer, F. (2000). Sentimientos (in)apropiados de las mujeres migrantes: Hacia una nueva ciudadanía. En D. Barrera y C. Oehmichen (Coords.), Migración y relaciones de género en México (371-388). México: Grupo Interdisciplinario sobre Mujer, Trabajo y Pobreza, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas. [ Links ]

Cornelius, W. A., FitzGerald, D., Lewin, F. P. y Muse-Orlinoff, L. (2010). Mexican Migration and the US Economic Crisis. A Transnational Perspective. California, Estados Unidos de América: Center for Comparative Immigration Studies, University of California. [ Links ]

De Genova, N. (2002). Migrant “Illegality” and Deportability in Everyday Life. Annual Review of Anthropology, 31, 419-447. [ Links ]

Dinan, S. (14 de agosto de 2017). Dreamers face immigration showdown over amnesty with Trump, courts. The Washington Times. Recuperado de http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2017/aug/14/daca-faces-challenges-trump-courts/ [ Links ]

Dowling, J. A. e Inda, J. X. (Eds.). (2013). Governing Immigration Through Crime. A Reader. California, Estados Unidos de América: Stanford California Press. [ Links ]

Fix, M. E. y Zimmermann, W. (2001). All Under One Roof: Mixed-Status Families in an Era of Reform, International Migration Review, 35(2), 397-419. [ Links ]

Hughes, E. (1960). The Profession in Society. The Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science, XXVI(1), 54-61. [ Links ]

Kochhar, R. (2008). Latino Labor Report: Construction Reverses Growth for Latinos. Washington, Distrito de Columbia, Estados Unidos de América: Pew Hispanic Center. [ Links ]

______ (2009). Unemployment Rises Sharply Among Latino Immigrants in 2008. Washington, Distrito de Columbia, Estados Unidos de América: Pew Hispanic Center. [ Links ]

Le Breton, D. (2012). Por una antropología de las emociones. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios sobre Cuerpos, Emociones y Sociedad, 4(10), 69-79. Recuperado de http://www.relaces.com.ar/index.php/relaces/article/view/208 [ Links ]

Levine, D. y Cooke K. (14 de febrero de 2017). Mexican ‘DREAMer’Nabbed in Immigration Crackdown. Recuperado de http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trump-immigration-arrest-exclusiv/mexican-dreamer-nabbed-in-immigrant-crackdown-idUSKBN15T307 [ Links ]

Mathema, S. (9 de enero de 2017). Ending DACA Will Cost States Billions of Dollars. Recuperado del sitio de Internet Center for American Progress: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/immigration/news/2017/01/09/296125/ending-daca-will-cost-states-billions-of-dollars/ [ Links ]

Merica, D. (16 de agosto de 2017). Trump Says Both Sides to Blame Amid Charlottesville Blacklash. Recuperado de CNN politics: http://edition.cnn.com/2017/08/15/politics/trump-charlottesville-delay/index.html [ Links ]

O´Neil, H. (25 de agosto de 2012). U. S. Immigration Policy Splits Families when Parents are Deported. The Denver Post. Recuperado de http://www.denverpost.com/nationworld/ci_21401857/u-s-immigration-policy-splits-families-when-parents#ixzz24hrk0418 [ Links ]

Suárez-Orozco, C., Suárez-Orozco, M. y Todorova, I. (2008). Learning a New Land. Immigrant Students in American Society. Massachussetts, Estados Unidos de América: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Truax, E. (2013). Dreamers. La lucha de una generación por su sueño americano. México: Océano. [ Links ]

United States Census Bureau. (2010). QuickFacts, United States. Recuperado de https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045216 [ Links ]

United States Citizen and Immigration Services (USCIS). (2012). Consideration of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). Recuperado de http://act.americasvoiceonline.org/page/m/327377f8/1fb6e4af/1e93d9fc/6f20de74/2111572833/VEsH/ [ Links ]

______ (2015). Immigration and Citizenship Data. Recuperado de https://www.uscis.gov/tools/reports-studies/immigration-forms-data [ Links ]

Wong, T. K., García, A. D., Abrajano, M., FitsGerald, D., Ramakrishnan, K. y Le, S. (15 de septiembre de 2013). Undocumented No More. A Nationwide Analysis of Deferred Action for Chilhood Arrivals, or DACA. Recuperado de https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/immigration/reports/2013/09/20/74599/undocumented-no-more/ [ Links ]

REFERENCES

Alejandro. (Julio de 2013). Entrevistado por la autora, Santa María, California, Estados Unidos de América. [ Links ]

Alfredo. (Julio de 2013). Entrevistado por la autora, Santa María, California, Estados Unidos de América. [ Links ]

Ana. (Junio de 2013). Entrevistada por la autora, Santa María, California, Estados Unidos de América. [ Links ]

Aurelio. (Octubre de 2016). Entrevistado por la autora, octubre, Santa María, California, Estados Unidos de América. [ Links ]

Carmen. (Octubre de 2014). Entrevistada por la autora, Santa María, Estados Unidos de América. [ Links ]

Carmen. (Febrero de 2015). Entrevistada por la autora, Santa Maria, California, Estados Unidos de América. [ Links ]

Cata. (Octubre de 2016). Entrevistada por la autora, Santa María, California, Estados Unidos de América. [ Links ]

Felicia. (Febrero de 2015). Entrevistada por la autora, Santa María, California, Estados Unidos de América. [ Links ]

Felipe. (Septiembre de 2012). Entrevistado por el autor, Santa María, California, Estados Unidos de América. [ Links ]

Gerardo. (Febrero de 2015). Entrevistado por la autora, Santa María, California, Estados Unidos de América. [ Links ]

Teresa. (Octubre de 2014). Entrevistado por la autora, Santa María, California, Estados Unidos de América. [ Links ]

1This name originates from the Dream Act (Development Relief and Education for Alien Minors), which was brought before the Senate by two senators in 2001 and failed to pass.

2ICE stands for Immigration and Customs Enforcement. It is part of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and aims to identify and investigate any problem concerning U.S. border security. Part of its work involves removals, or what in Mexico we call deportations.

3Key points: a) new requests to enter DACA will not be accepted; b) renewals will be accepted until October 5, 2017; c) for cases in which DACA will expire by March 5, 2018, renewals should be sought before October 5, 2017; and d) as of these dates, once the permissions expire, young people will resume being undocumented.

4For an analysis of how young Mixteco indigenous immigrants have perceived and reacted to DACA, see Barros and García (2015).

5DREAM is an acronym for Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors. The sponsors of the Dream Act essentially ask that undocumented young people wishing to enter university be subjected to the same conditions as U.S. residents, with no differences based on ethnicity and national origin. Undocumented youth pay tuition up to three times higher than residents, making their integration difficult. This initiative was presented in Congress in September 2006 and has not been approved. The only state that approved its own Dream Act was California, in 2013.

6Young people must have the following characteristics: be under the age of 31 as of June 2012; have arrived in the United States before reaching 16 years of age; have continuously resided in the United States for a minimum of three years before June 15, 2012, and at the time of requesting consideration for deferred action with United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS); have continuously resided in the United States since June 15, 2007, up to the present time; currently be in school, or have graduated or obtained a certificate of completion from high school, possess a general education development (GED) certificate, or be an honorably discharged veteran of the Coast Guard or Armed Forces of the United States; have not been convicted of a felony, significant misdemeanor, or three or more other misdemeanors, and not otherwise pose a threat to national security or public safety (USCIS, 2012).

7In just the first six months of 2012, 45 000 mothers and fathers were deported, and more than 5 100 child citizens in 22 states were placed in state custody in foster care programs where families provide temporary care for children until they are adopted permanently or reach adulthood and can take care of themselves (O’Neil, 2012).

8By August 2013, only 49% of the eligible population had presented requests, according to Obama administration figures. Of these, 68% were from Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras; 24% were high school students, and 44% were not enrolled in university nor possessed a university degree (Wong et al., 2013).

9It is important to explain that the ages of these young people at the time of arrival in the United States vary widely. Some arrived as children and attended elementary school, and thus, it was easier for them to learn English. For those who were older, it was more difficult to learn the language and adapt to the educational system, and they were less likely to receive their high school diploma. Of the young people interviewed, four women and two men entered elementary school upon arrival, while one woman and four men entered middle school. None were of high school age. Knowing English, understanding the American educational system, and having a high school diploma gave those wishing to apply for DACA an advantage. This is an issue that requires further study. For more on the issue of education and language, see Suárez-Orozco, Suárez-Orozco and Todorova (2008).

Received: March 27, 2017; Accepted: September 05, 2017

texto en

texto en