BACKGROUND

In December 2019, an outbreak of febrile respiratory syndrome due to pneumonia caused by a new coronavirus was identified in the city of Wuhan, China (Li et al., 2020a). The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic are severe, producing extremely high death rates. Since SARS-COV-2 was detected, over ninety million people worldwide have been infected and over two million have died from coronavirus. (COVID-19; Lopez-Leon et al., 2021). The uncertainty and unpredictability of COVID-19 threaten both physical and mental health in terms of emotions and cognition (Li, Wang, Xue, Zhao, & Zhu, 2020b). Approximately fifty per cent of people who experience the loss of a loved one due to unnatural causes subsequently suffered prolonged grief disorder, associated with increased morbidity. Death from COVID-19 usually occurs under specific circumstances: isolation, sudden death preceded by uncertainty, states of anguish at having to make quick, drastic decisions, often conflicting with the initial wishes of the patient (such as orotracheal intubation), the lack of funeral rituals, farewells or physical contact, which even leads to denial after the death of the person with COVID-19. In this context, death can leave sequelae in the form of prolonged mourning for family members, making it impossible to accept it and exacerbating the pain and suffering caused by the loss. A study undertaken of people who have lost a loved one to COVID-19 found a 37.8% prevalence of prolonged grief disorder (PGD) and a 39.9% prevalence of persistent complex bereavement disorder (PCBD; Tang & Xiang, 2021) . PGD is therefore expected to become a significant public health concern globally. Due to the increase in the prevalence of PGD following COVID-19 as well as the associated morbidity and mortality, it is essential to know how this disorder can be treated in these circumstances. However, due to the relative novelty of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic as well as the minimum period required to diagnose PGD/PCBD (six to twelve months), limited information is available on interventions that can be provided for PGD following the loss of a loved one to COVID-19. This study was undertaken to identify the main evidence-based, empirically validated psychotherapeutic techniques used for treating patients with PGD and to suggest a therapeutic approach for managing COVID-19 grief.

METHOD

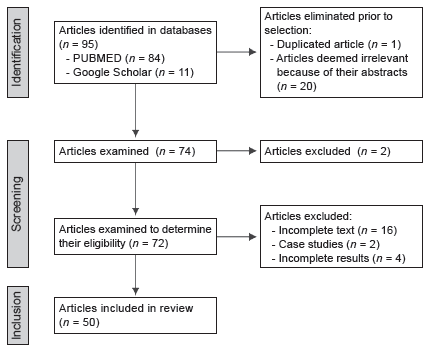

A literature search was conducted using the PUBMED and Google Scholar search engines, published from January 2016 to September 2021, with the English and Spanish terms for prolonged grief disorder, persistent complex bereavement disorder, complicated grief, COVID-19 grief, cognitive behavioral therapy, treatment, psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. These terms were used in combination with the operators “and” “or” and “not” to narrow down results. References from PUBMED and Google Scholar specifically related to prolonged grief disorder were selected according to the criteria of the eleventh revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), Persistent Complex Grief Disorder according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), or Complicated Grief. Articles describing case studies were ruled out, with priority being given to randomized clinical trials and systematic reviews. Fifty articles were eventually selected (Figure 1).

RESULTS

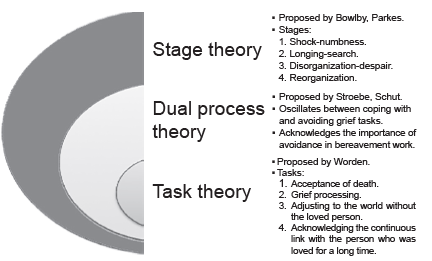

Over the course of their lifetime, most people experience the loss of a loved one due to a range of causes including illness, disasters, accidents, and suicide. Death is irreversible, and in most cases, the bereaved person does not require professional assistance (Nakajima, 2018). Grief is perceived as a normal reaction, with most people eventually adapting to their new lifestyles with the physical absence of their loved ones. For many researchers, the most important aspect distinguishing normal from pathological grief is the process itself. It is therefore essential to know what a normal grief process encompasses. Various theories exist such as the stage theory proposed by Bowlby and Parkes, according to which the period of adjustment to grief lasted from a few weeks to several months, entailing four stages. Worden suggested changing the term from “stage” to “task,” which involves the bereaved person in an active process and identified four basic tasks. Stroebe & Schut proposed the dual process model to explain how people come to terms with the death of their loved ones, recovering from discomfort in daily life through a dynamic process oscillating between loss and restoration, coping with and avoiding the work of mourning (Figure 2).

Types of grief

The concept of pathological grief is widely accepted among researchers. Grief that deviates from the normal process is referred to in various ways, such as delayed grief, distorted grief, complicated grief, traumatic grief, PGD, and persistent complex bereavement disorder (PCBD; Maciejewski, Maercker, Boelen, & Prigerson, 2016). Approximately 10% of a group of bereaved patients experience intense grief that persists longer than expected after a natural death, while 50% do so when death is due to unnatural causes. This type of grief is characterized by an overwhelming, persistent sense of longing and concern for the deceased and significant emotional distress, together with impaired functionality (Djelantik, Smid, Mroz, Kleber, & Boelen, 2020; Lundorff, Holmgren, Zachariae, Farver-Vestergaard, & O՚Connor, 2017).

Since the evidence supports prolonged grief disorder as a new diagnostic category, both the World Health Organization (WHO) and the American Psychiatric Association have introduced what appears to be a version of PGD into their own diagnostic classification systems: the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) and the DSM-5 (Table 1). However, lack of standardization regarding the terminology and conceptualization of the disorder has created confusion about prolonged grief disorder and its relationship with normal grief due to loss and other mental disorders (Maciejewski et al., 2016).

Table 1 Persistent complex grief disorder criteria according to the DSM-5

| A. | The individual has experienced the death of someone with whom they had a close relationship. | |

| B. | Since that person’s death, at least one of the following symptoms has been present on more days than not at a clinically significant level, persisting for at least twelve months for bereaved adults and six months for bereaved children: |

|

| 1. | Persistent yearning/longing for the deceased. In young children, longing can be expressed through play and behavior, including behaviors that reflect separation as well as a re-encounter with a caregiver or another attachment figure. |

|

| 2. | Intense grief and emotional distress in response to the person’s death. | |

| 3. | Concern regarding the deceased. | |

| 4. | Concern about the circumstances of the death. In children, this concern over the deceased can be expressed through the content of the game and behavior and can extend to concern over the possible deaths of other people close to them. |

|

| C. | Since the person’s death, at least one of the following symptoms has been present on more days than not at a clini- cally significant level, persisting for at least twelve months for bereaved adults and six months for bereaved children: |

|

| Discomfort related to the person’s death | ||

| 1. | Significant difficulty accepting death. In children, this depends on the child’s ability to understand the meaning and permanence of death. |

|

| 2. | Experiencing disbelief or emotional anesthesia in relation to the loss. | |

| 3. | Difficulty remembering the deceased in a positive light. | |

| 4. | Bitterness or anger in relation to the loss. | |

| 5. | Maladaptive evaluations about oneself in relation to the deceased or their death (such as self-incrimination). | |

| 6. | Excessive avoidance of memories of the loss (such as avoiding individuals, places, or situations associated with the deceased. In children, this may include avoiding thoughts and feelings about the deceased). |

|

| Social/Identity Alteration | ||

| 7. | Wishing to die to be with the deceased. | |

| 8. | Difficulty trusting other people since the person’s death. | |

| 9. | Feelings of loneliness or detachment from other individuals since the person’s death. | |

| 10. | Feeling that life is meaningless or empty without the deceased, or believing that one cannot function without the deceased. |

|

| 11. | Confusion about one’s role in life, or a diminished sense of self-identity (such as feeling that a part of oneself died with the deceased). |

|

| 12. | Difficulty in or reluctance to maintain interests (such as friendships, activities) or make plans for the future since the loss. |

|

| D. | The disturbance causes clinically significant distress or dysfunction in social, occupational, or other significant areas of functioning. |

|

| E. | The grief reaction is out of proportion to or inconsistent with cultural, religious, or age-appropriate norms. | |

| Specify whether this is: | ||

| Traumatic grief: Grief due to homicide or suicide with persistent distressing concerns about the traumatic na- ture of the death (often in response to reminders of the loss), including the last moments of the deceased, the degree of suffering and mutilating injuries, or the malicious or intentional nature of the death. |

||

Source: APA (2014).

Note: DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition

Likewise, WHO proposed incorporating PGD into the ICD-11 with the following criteria:

PGD is a disorder in which, following the death of someone close to the bereaved person, there is a persistent and pervasive grief response, characterized by longing for the deceased person or persistent worry accompanied by intense emotional pain (such as sadness, guilt, anger, denial, blame, difficulty coming to terms with their death and feeling that one has lost a part of oneself, an inability to experience a positive mood, blunted affect, and difficulty engaging in social or other activities).

The grief response has persisted for an unusually long period after the loss (for at least six months) and clearly longer than expected according to social norms and the individual’s cultural and religious context.

The disturbance causes significant impairment in personal, familial, social, educational, occupational, and other key areas of behavior (Mauro et al., 2019).

The main differences between PGD and PCBD are semantic rather than substantive. The scientific and clinical community must recognize that PGD and PCBD are fundamentally the same disorder and should work towards a common understanding of this disorder and adopt useful ways of recognizing it clinically. The term PGD captures the essence of the disorder, facilitates its understanding, and therefore supports clinical judgment in its diagnostic evaluation (Maciejewski et al., 2016). PCBD will be replaced by another diagnostic name, PGD, in section two, under the criteria and diagnostic codes in the next DSM-5 (Boelen & Lenferink, 2020). Research has concluded that PGD is a different mental disorder from others, such as major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Several characteristics have been identified that predict a greater risk of developing PCBD (Table 2).

Table 2 Risk factors for developing persistent complex grief disorder/severe grief

| Pre-loss factors | Post-loss factors |

|---|---|

| Female | Social circumstances |

| Elderly | Resources available after death |

| Low socioeconomic status | Limited social support |

| Living without a partner | Interference with the natural grieving process |

| Nature of death (unnatural death) | Inability to follow cultural death and mourning practices |

| Relationship and care roles | Psychoactive substance use |

| History of childhood trauma | |

| Previous bereavement | |

| Pre-existing depression and anxiety disorders | |

| Being unprepared for the death |

Source: Compiled by the author, based on data from Olaolu et al. (2020), Tang and Xiang (2021), Thimm, Kristoffersen, and Ringberg, (2020).

Grief and comorbidities

Several studies have identified associations between grief and an increased risk of developing physical and mental health problems (Stroebe, Stroebe, Schut, & Boerner, 2017), together with a high risk of death after grief (Ytterstad & Brenn, 2015); this is known as the widowhood effect and has also been identified following the death of a child or a sibling in childhood (Yu et al., 2017).

Other effects on physical health include cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (Tofler et al., 2020). Associations have also been reported with infections (Lu et al., 2016) and Type I diabetes mellitus (Virk, Ritz, Li, Obel, & Olsen, 2016). As for mental health, findings suggest an increased risk of depression, anxiety, and substance use disorder after bereavement (Keyes et al., 2014).

Grief during the COVID-19 pandemic

According to recent studies, for every loss due to COVID-19, approximately nine family members will be affected and in mourning (Verdery, Smith-Greenaway, Margolis, & Daw, 2020). It is estimated that the massive grief following COVID-19 will leave approximately sixteen million people in mourning worldwide. Since including the deaths of close friends could push this figure even higher, being able to provide proper care for people in mourning following COVID-19 is becoming a global challenge (Tang & Xiang, 2021). Researchers have expressed concern that circumstances related to COVID-19 deaths will lead to a high global prevalence of PGD (Eisma, Boelen, & Lenferink, 2020) cases. COVID-19 deaths are usually unexpected, which has led to higher levels of prolonged grief symptoms in mourners in various countries (Djelantik et al., 2020). Moreover, COVID-19 deaths can be traumatic because people may experience the pandemic as a disaster, while survivors of unnatural events such as disasters and accidents are at higher risk of developing prolonged grief (Yi et al., 2018). The traumatic nature of COVID-19 deaths is related to the inability to visit the dying person or to be able to engage in traditional funeral protocols and other rituals. One study revealed that mourners who had not had a chance to say farewell to a person who had died in an intensive care unit were two to three times more likely to develop PGD (Kentish-Barnes et al., 2015). As the subjective experience of a traumatic death increases, so does the severity of PGD symptoms (Tang & Chow, 2017). A recent study involving forty-nine Dutch people who had experienced COVID-19 grief reported more severe bereavement than those mourning a natural death, and similar bereavement levels to those who had experienced a death due to unnatural causes (Eisma, Tamminga, Smid, & Boelen, 2021). Another study in China, conducted on people who had lost a loved one to COVID-19, found that a 37.8% prevalence of PGD according to the ICD-11 and a 39.9% prevalence of PCBD according to the DMS-5. Factors associated with more severe PGD or PCBD symptoms after losing someone close to them to COVID-19 (Tang & Xiang, 2021) have been identified, such as the absence of traditional funeral rituals, when an unexpected or traumatic death occurs, when a partner, child, parent or grandparent dies, or having had a conflict with the deceased.

Evidence-based techniques for managing prolonged grief disorder

Two successful randomized controlled trials have examined individual treatment for prolonged grief disorder. The first is a trial with two active conditions comparing the treatment of complicated grief (including three phases: the introductory phase, where the therapist provided information on normal and complicated grief and described the model of the dual adaptive coping process involved and recovering a satisfying life and adjusting to loss. In this case, the therapist not only focused on loss but also on personal life goals. In the middle phase, the therapist addressed both stages in tandem, and in the final phase, therapist and patient together reviewed progress, plans for the future and feelings related to the end of treatment. Complicated grief treatment used cognitive behavioral therapy techniques focussing on loss, which included retelling the story of the loss and working on coping with situations the person was avoiding. Cognitive techniques included an imaginary conversation with the dead person and working with memories in interpersonal therapy (which also used three phases: an introductory phase during which symptoms were reviewed and identified, a middle phase dealing with grief and other interpersonal problems and a completion phase, during which the benefits of treatment and the person’s life project were reviewed). Feelings about the end of treatment were also discussed. Interpersonal therapy techniques helped reestablish relations and restore effective interpersonal functioning. It was found that both treatments produced an improvement. However, the range of responses was greater (51%) and the response time for treating complicated grief quicker than with interpersonal therapy (28%; Shear, Frank, Houck, & Reynolds, 2005). The second is a trial comparing the efficacy of an Internet-based cognitive behavioral intervention. This program combined established psychotherapy methods with new technology. Therapists and patients communicated exclusively by email. This five-week intervention comprised three modules. The first involved exposure to signs of grief, the second cognitive restructuring and the third integration and restoration), with an untreated control group (on a waitlist). The treatment group was found to have improved significantly in relation to subjects on the waitlist as regards symptoms such as intrusion, advoidance, maladaptive behavior, and psychopathology in general (Wagner, Knaevelsrud, & Maercker, 2006). Another study was conducted with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) applied to prolonged mourning, consisting of twenty-five sessions, five of which were optional (anniversaries, celebrations, family sessions, and legal proceedings). The remaining twenty sessions were standard treatment and divided into three parts. The first part consisted of seven sessions focused on stabilizing, motivating, and exploring grief. The second comprised nine sessions on relaxation techniques, confrontation, and reinterpretation of cognitions and perceptions and the third consisted of four sessions focusing on the future while maintaining a healthy bond with the deceased. Sessions were held weekly, and lasted fifty minutes, with the exception of two ninety-minute sessions. This treatment was found to be highly effective in terms of reducing the severity of grief. The controlled effect size for the improvement of grief symptoms in people who completed CBT treatment was d = 1.61 (Rosner, Pfoh, Kotoučová, & Hagl, 2014). Wagner and Maercker tested the long-term effects of an Internet-based cognitive behavioral intervention, reporting that the decrease in PGD symptoms remained eighteen months after treatment (Wagner & Maercker, 2007). In another 1.5-year follow-up study including fifty-one patients with clinically significant prolonged grief symptoms who had participated in a randomized controlled trial in which they had received integrative CBT for PDD, this intervention proved effective in the long term. In terms of clinical significance, 64% of those who completed the study had achieved or maintained recovery at follow-up (Rosner, Bartl, Pfoh, Kotoučová, & Hagl, 2015).

The effectiveness of CBT was compared with a non-specific treatment with supportive therapy. Fifty-four bereaved persons with clinically significant levels of complicated grief were assigned to one of three treatment conditions: (a) six sessions of cognitive restructuring (CR), and six sessions of exposure therapy (ET), (b) the same interventions administered in reverse order (ET+CR) and (c) twelve support therapy sessions. The results showed that the two cognitive behavioral therapy conditions achieved greater improvement in complicated grief and overall psychopathology than supportive therapy. Comparing the cognitive behavioral conditions showed that exposure alone was more effective than cognitive restructuring alone and that adding exposure therapy to cognitive restructuring enhances improvement more than adding cognitive restructuring to exposure therapy (Boelen, de Keijser, van den Hout, & van den Bout, 2011).

Other randomized studies have demonstrated the efficacy of both interpersonal therapy and complicated grief-focused therapy in treating PGD, with significantly better results being reported with complicated grief-focused therapy. This shows that it achieved greater reductions in depressive and anxious symptoms, which included negative thoughts about the future and grief related avoidance, in addition to a more significant decrease in depression among those who did not take antidepressants (Simon, 2015; Glickman, Shear, & Wall, 2016).

Systemic family therapy focuses on improving the ability of family members to support each other and develop coping strategies for various situations such as chronic diseases, such as cancer. It consists of families telling the story of the disease, therapists exploring the types of communication within each family, and cohesion and conflict resolution together with family values, beliefs, roles, and expectations. The therapy was provided in six and ten sessions. This type of therapy has been reported to decrease the severity and development of prolonged grief disorder (Kissane et al., 2016).

One interesting systematic review examines the effectiveness of interventions focusing on people who suffer from grief following the suicide of a loved one. Due to the multiple characteristics surrounding this type of death, the associated grief can become pathological, traumatic, or complicated in nearly half of all cases. Seven interventions were evaluated: two based on the cognitive behavioral method, four consisting of bereavement groups, and one using writing therapy (subjects wrote about their grief experience four times for fifteen minutes over a fortnight). Five of the seven interventions proved efficacious in decreasing grief intensity on at least one outcome measure. For example, group therapy tends to be effective in decreasing symptom intensity in uncomplicated grief whereas writing therapy (by inviting subjects to write openly and in a safe environment about suicidal thoughts and emotions) has been shown to reduce specific aspects of suicide-related grief compared to those randomly assigned to a control condition. Cognitive behavioral programs proved useful for a subgroup of people with complicated grief with high levels of suicidal ideation (Linde, Treml, Steinig, Nagl, & Kersting, 2017).

The metacognitive model suggests that psychological disorders are the result of repetitive negative thinking about a perceived belief, leading to an attentional cognitive syndrome that includes worry/rumination, threat monitoring, and maladaptive coping behaviors (Wenn, O՚Connor, Breen, Kane, & Rees, 2015). A pilot study was conducted to test the efficacy and feasibility of Metacognitive Grief Therapy (MCGT), specifically designed for prolonged grief symptoms, in which twenty-two adults who were randomly assigned to a waitlist (n = 10) or intervention (n = 12) group participated, with follow-up at three and six months and six two-hour group MCGT sessions a week. Subjects who received MCGT showed significant improvement in PGD symptomatology, depression, anxiety, stress, rumination, and quality of life after MCGT compared with waitlist participants offered MCGT after posttest assessment (Wenn, O՚Connor, Kane, Rees, & Breen, 2019).

Treatments within the realm of cognitive behavioral therapy have proved to be of the greatest empirical use for a wide range of psychiatric disorders. However, a meta-analysis of 125 studies of this traditional form of outpatient psychotherapy found that 50% of patients withdrew from treatment early, with nearly forty percent dropping out after the first or second visit. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) helps subjects come to terms with the fact that pain, loss, illness, fear, and anxiety are inevitable characteristics of human life. Its goal is therefore not to eliminate or suppress these experiences but rather to emphasize the search for valuable areas of life and directions in response to these painful experiences. Developing psychological flexibility through ACT achieves greater commitment to a meaningful life, despite experiencing negative thoughts or emotions (Dindo, Van Liew, & Arch, 2017). ACT is used to treat a range of mental health conditions involving experiential avoidance, including grief. A study conducted at the Suicide Grief Clinic at the University Center for Health Sciences of the University of Guadalajara, Mexico evaluated complicated grief in patients treated with ACT. The study population comprised thirty-nine adults (thirty-two women and seven men) who attended eight weekly two-hour sessions. In the therapeutic process, the issue of emotions was addressed through questions oriented towards spirituality. The intervention focused on the subject’s own moral and ethical values. Some exercises consisted of locating people in the present and using metaphor to begin to create a new conception of what death means for the mourner. It proved useful in the mourning process, as well in re-establishing spirituality, which is resignified and gives meaning to painful experiences (Villagómez-Zavala, Ornelas-Tavares, Franco-Chávez, Gutiérrez-Castillo, & Martínez-Becerra, 2020).

The Table 3 shows the techniques identified for PGD management.

Table 3 Psychotherapeutic techniques for treating prolonged grief disorder

| Technique | Objective | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD) |

To determine whether patients with PGD benefited from a new ther- apy: CBT for PGT: - Fifty-one patients (two groups: twenty-four in the treatment group and twenty-seven in the control group: waitlist). Twenty-five sessions: - Five optional sessions. - Seven stabilization and motivation sessions. - Nine sessions with relaxation, coping, and re-interpretation of cog- nition and perceptions techniques - Four sessions where a healthy bond is maintained with the de- ceased and the subject is encouraged to focus on the future. Weekly sessions for fifty minutes. |

- Highly effective in terms of reducing grief severity (Rosner et al., 2014). - Effective for subgroup of people with high levels of suicidal ideation (Linde et al., 2017). - Effect size for symptom improvement:d = 1.61 (Rosner et al., 2014). |

| * Fifty-one outpatients with clinically significant prolonged grief symptoms who participated in an RCT were followed up for 1.5 years after CBT for PGD. |

* CBT for PGD proved effective in the long run (Rosner et al., 2015). | |

| Internet-Based Therapy (CBT) |

- Five-week intervention. - Three modules: Exposure to signs of grief, cognitive restructuring and integration and restoration. - Therapists and patients communicated via email. - Evaluation through a 1.5-year follow-up after an Internet-based CBT intervention for complicated grief. - Group of patients (n = 22). |

- The reduction in PGD symptoms was maintained at 18-month follow-up (Wagner & Maercker, 2007). |

| Support Therapy | - Fifty-four PGD patients were assigned to three conditions, one of which was supportive therapy while the other two included CBT. - Weekly sessions. |

- They improve less than those receiving CBT (Boelen et al., 2011). |

| Interpersonal Therapy |

- It examined anxiety and depression symptoms in a sample of peo- ple assigned to complicated grief treatment (n = 35) or interperson- al psychotherapy (n = 34) in a RCT. - Sixteen weekly sessions- Three phases: Introduction, middle phase, and ending. |

- Complicated grief therapy had a significantly greater effect and greater tolerability compared with bereavement-fo- cused Interpersonal Therapy in older adults who have ex- perienced bereavement and achieved a greater decrease in anxiety and depression symptoms including negative thoughts about the future and grief-related avoidance (Shear et al., 2014; Glickman et al., 2016; Simon, 2015). |

| Bereavement groups |

- Systematic review of seven intervention studies (two CBT-based, four bereavement groups, and one writing therapy where students were invited to write openly and in a safe environment about sui- cidal thoughts and emotions). |

- They are effective for de-escalating uncomplicated grief (Linde et al., 2017). |

| Family or Systemic Therapy |

- Randomized controlled study of family therapy for families at risk of dysfunctional relationships when one of their members has ad- vanced cancer. - Six hundred and twenty patients (170 families) were recruited and divided into three levels of dysfunction. - They were assigned to standard care, including six to ten family intervention sessions. - Communication, cohesion, conflict resolution, family values, be- liefs, roles, and expectations were explored. |

- Family therapy given to high-risk families during palliative care and continued through bereavement decreases the severity of complicated grief and the development of pro- longed grief disorder (Kissane et al., 2016). |

| Group Metacognitive Therapy for prolonged grief (TMCD) |

- Randomized controlled pilot study to test the efficacy and feasibil- ity of MCGT in reducing psychological distress and impaired func- tioning as a result of bereavement. - Twenty-two adults with prolonged grief symptoms (n = 10 for wait- list and n = 12 for intervention). - Three and six month follow-up. - Six two-hour group sessions a week. |

- Promising results for the usefulness of MCGT group thera- py to reduce psychological distress and enhance quality of life. - Subjects showed significant improvement in PGD symptom- atology, depression, anxiety, stress, rumination, and quality of life after MCGT compared with subjects on waitlist (Wenn et al., 2019). |

| Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) |

- Thirty-nine adults (thirty-two women and seven men) experiencing grief, received eight two-hour weekly sessions. - Intervention focusses on subjects’ moral and ethical values. - Exercises to place people in the present, use of metaphor. |

- This has proved useful in the mourning process as well as the reestablishment of spirituality, which is resignified and gives meaning to painful experiences (Villagómez-Zavala et al., 2020) . |

| - Eighteen studies with 1,088 subjects were included in the review. | - Meta-analysis suggests that ACT significantly reduces depres- sive symptoms compared to the control group (CBT), espe- cially at three month follow-up, in the group of adults and those with mild depression (Bai, Luo, Zhang, Wu, & Chi, 2020). |

|

| - Thirty-six randomized controlled trials | - A review of thirty-six RCTs of anxiety and depression treat- ments: ACT appears to be more effective than waitlist and treatment as usual with effects relatively equivalent to CBT (Twohig & Levin, 2017). |

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Note: PGD: Prolonged Grief Disorder, CBT: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, RCT: Randomized Clinical Trial, MCGT: Metacognitive Grief Therapy, ACT: Acceptance and Commitment Therapy.

Only limited information on Pharmacological Therapy focusing on the management of prolonged grief symptoms is available. Three open-label trials on grief-associated depression were identified. The first open-label trial was conducted by Jacobs et al. with ten widows and widowers who received desipramine (75 mg to 150 mg/day), only three of whom experienced a significant reduction in grief intensity. The second open-label trial, conducted by Pasternak et al. examined the efficacy of nortriptyline for grief-related depressive symptoms, sleep, and grief severity in thirteen widows, whose clinical improvement was marginal. In the third open-label trial conducted by Zisook et al. on grief-related depressive symptoms eight weeks after losing their wives, which treated subjects with bupropion at doses of 150-300 mg/day, there was a 36% dropout rate. It was concluded that tricyclic antidepressants may be effective, especially for bereavement-related depression symptoms, although their effect is not as significant or specific for bereavement severity. In regard to benzodiazepines, there are no reports of primary efficacy for complicated grief treatment. Conversely, in a randomized controlled trial investigating the use of diazepam versus a placebo in medical treatment for recent bereavement, with seven-month follow-up, those who received diazepam experienced more sleep problems than those assigned to the placebo group. The most recent studies show that psychotherapeutic interventions for prolonged grief may be more effective in combination with the administration of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs; Bui, Nadal-Vicens, & Simon, 2012).

A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial was conducted to assess the efficacy of antidepressant pharmacotherapy, with and without psychotherapy for complicated grief in the treatment of prolonged grief, involving 395 adults. Psychotherapeutic treatment focusing on complicated grief consisted of a protocol with sixteen sessions. The first to the third session included recording the history of relationships and grief experience and beginning daily grief monitoring and psychoeducation. Aspirational work goals were introduced and a joint session with a significant person were introduced. Sessions four to nine included exposure procedures with imagery and situational procedures, and work was carried out with memories and images. Session ten was a review session, while sessions eleven through sixteen included an imaginary conversation with the deceased. Participants were randomly assigned to groups with citalopram (n = 101), a placebo (n = 99), psychotherapeutic treatment for complicated grief plus citalopram (n = 99), and psychotherapeutic treatment for complicated grief plus a placebo (n = 96). Prolonged grief treatment was found to be the treatment of choice, while the addition of citalopram proved to improve the therapeutic response in patients with co-occurring depressive symptoms. Psychotherapeutic treatment for complicated grief proved more effective for depression than either interpersonal psychotherapy or antidepressant drugs (Shear et al., 2016). Another multicenter clinical trial included 394 adults and examined the relationship between maladaptive thoughts and suicidal risk at baseline and post-treatment. It also explored the effect of treatment with and without complicated grief therapy compared with the use of citalopram or placebo. An analysis of the scores of the typical belief questionnaire revealed a significant decrease in these symptoms in subjects who received complicated grief therapy with citalopram compared with those who were only given citalopram (Skritskaya et al., 2020).

Addressing grief in relatives of patients who died from COVID-19

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the uncertainty surrounding the disease and the absence of the usual rituals can hamper the acceptance of death (Mayland, Harding, Preston, & Payne, 2020). The COVID-19 crisis has combined various mental health stressors that have been assessed individually in other contexts yet never been seen together, since this is an unprecedented global disaster (Gesi et al., 2020). In a narrative review conducted by nursing staff to identify the available evidence on recommendations for addressing grief and death in relatives of COVID-19 patients, it was found that social distancing measures hamper the normal mourning process by eliminating the symbolism of mourning. The need to share the experience socially with gestures that show accompaniment and empathy has been acknowledged. This can now be done through social networks, diary writing, letters of condolence, support programs, active listening, reinforcing self-care, and attention to spirituality. Fluid, effective communication should be maintained between health personnel and the family as well as between isolated patients and their loved ones by using new technologies or transmitting the message in writing, implementing a person’s living will or advance directive and following up on the bereaved family member in the short, medium, and long term (Araujo Hernández, García Navarro, & García-Navarro, 2021).

The possibility of reducing the psychological impact on those in mourning during this pandemic is limited, since only a few risk factors for prolonged grief can be altered through intervention (Gesi et al., 2020). These strategies include: 1) promoting communication between the patient, the primary caregiver and the health professional when possible through new technology; 2) ensuring individualized attention in decision-making, advanced care planning, and support for the patient’s beliefs and wishes; and 3) future commemoration (Mayland et al., 2020). Involving family members in decision-making correlates with a reduction in symptoms of prolonged grief among survivors. Since living alone after the death of a loved one has been associated with the presence of symptoms of prolonged grief, it is important to provide bereaved family members with effective social support (Gesi et al., 2020).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The main finding of this narrative review is that there is not yet sufficient information to enable one to recommend specific psychotherapeutic interventions based on efficacy criteria in the medium and long term, for people suffering from the loss of a loved one following COVID-19. Various techniques have proved effective in specific aspects in the treatment of patients with prolonged grief disorder, but there is a lack of multidimensional studies that would make it possible to document the comparative efficacy between them and on various areas of interest for psychotherapy. This is significant if one considers that the frequency of people with COVID-19-related prolonged grief disorder continues to increase worldwide (Tang & Xiang, 2021). It was found that the characteristics of a COVID-19 death resemble those of a traumatic death caused by a natural disaster, with the attendant losses this entails, because of the psychosocial conditions surrounding it. It combines factors that exacerbate psychological, social, physical, economic, and labor stress in a way that increases the risk of those grieving the death of a loved one from COVID-19 of having a PGD by up to 40%. This, in turn, is associated with greater psychiatric and physical morbidity, and higher death rates, which is why it is estimated that PGD will become a public health problem while at the same time posing a challenge to providing efficient management. The review conducted by the authors found that various terms are used to refer to grief that deviates from the normal process, which can lead to confusion around diagnosis and treatment. Nevertheless, the most widely recognized concepts are persistent complex grief disorder, according to the diagnostic classification of the DSM-5 (APA, 2014), and prolonged grief disorder according to the ICD-11. For Maciejewski et al. (2016), since both diagnoses are essentially the same disorder, MCGT is expected to be replaced by PGD, in section two, under the diagnostic criteria and codes in the next version of the DSM-5. The review identified various techniques used for the management of PGD, with CBT applied to Prolonged Grief being found to be highly effective in terms of reducing the severity of grief in individuals who complete treatment (Rosner et al., 2014). It is effective in the long term according to the follow-up study at one and a half years. Likewise, exposure techniques with behavioral and emotional elements were found to be more effective than cognitive restructuring for mourning (Boelen et al., 2011). Although there is evidence of the effectiveness of CBT applied to grief, nearly half the patients withdrew from treatment early after the first or second visit (Dindo et al., 2017). It is important to note that in times of pandemic, the use of social networks can become an effective means for people who have difficulty obtaining in-person treatment. There is evidence that Internet-based CBT decreases PGD symptoms and that this benefit remains after a year and a half of follow-up (Wagner & Maercker, 2007). However, since prior to the conditions caused by the pandemic, the use of new technology to provide mental health care was limited, there are very few studies on the administration of remote care. In general, other interventions such as family therapy, grief groups, supportive therapy, and interpersonal therapy tend to show a favorable response compared to being on a waitlist, although less than CBT for PGD. The review found that Metacognitive Therapy specifically designed for prolonged grief disorder significantly improves the symptoms of PGD, depression, anxiety, stress, rumination, and quality of life (Wenn et al., 2019). The most recent therapies for grief management include ACT, which can be useful in the mourning process, as well as for restoring spirituality (Dindo et al., 2017).

Limited information was found on the pharmacological treatment of PGD. In the trials where tricyclic antidepressants were used, improvement was insignificant. In the case of bupropion, there was a dropout rate of almost 40%, wherea with the use of benzodiazepines (Diazepam), there are insufficient reports of primary efficacy coupled with increased problems of insomnia (Bui et al., 2012). The use of SSRIs (citalopram) was found to enhance the efficacy of psychotherapy for co-occurring depressive symptoms. The efficacy of purely pharmacological treatment for PGD management is limited, and better results have been reported if it is used in conjunction with psychotherapeutic treatment (Skritskaya et al., 2020).

There are undoubtedly limitations because there are no studies comparing the various psychotherapeutic techniques. Since there are even fewer studies of relatives of those who died from COVID-19 currently suffering from PGD, there is obviously a need for them. These studies would have to be adapted to the circumstances imposed by the pandemic, particularly social distancing. The search for and improvement of virtual psychotherapy strategies, as well as the reinforcement of social support networks and effective communication between the patient and the family and health personnel, are some of the proposals that can yield positive results. At the same time, it is necessary to standardize the apparently equivalent terms to refer to PGD in the available mental illness manuals, to improve both its identification and diagnosis, as well as the treatment and follow-up of this disorder.

Compiled by the author, based on data from Olaolu et al. (2020), Tang and Xiang (2021), Thimm, Kristoffersen, and Ringberg, (2020).

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)