INTRODUCTION

Intimate partner violence (IPV) has been defined as the abuse that occurs in a romantic relationship by both, current and former partner or dating partners, that causes physical, psychological or sexual harm. It is the most common form of violence against women, ranging from one episode of violence that could have lasting impact, to chronic and severe episodes over multiple years. IPV can include any of the following types of violence: physical, psychological, sexual, and controlling behaviors (World Health Organization, 2013; Pan American Health Organization, 2016). The experience of IPV in women has been associated with decreased quality of life (Achchappa et al., 2017; Alsaker, Moen, Morken, & Baste, 2018), presence of depressive disorders (DD), anxiety disorders (AD; Ahmadabadi et al., 2020; Chandan et al., 2020), and with risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors (World Health Organization, 2005; Devries et al., 2013). Female survivors of IPV are twice as likely to attempt suicide multiple times, and the social isolation they are forced by their partners, increase the risk (Morfín López & Sánchez-Loyo, 2015). The experience of IPV is a traumatic condition that activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal stress axis (HPA; Morris et al., 2020). The activation of corticotrophin releasing hormone (CRH) from the hypothalamus results in the release of the adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from the hypophysis, which stimulates cortisol secretion from the adrenal glands. Cortisol exerts its metabolic function to cope with the threat, but once stressor is over, triggers the negative feedback mechanism by inhibiting the CRH-ACTH activity (Mielock, Morris, & Rao, 2017; Morris et al., 2020). Most evidence has confirmed that prolonged stressors alter the functionality of the HPA axis reactivity (i.e., the pattern of cortisol response), negatively affecting physical and mental health. Then, it has been reported that the overproduction of cortisol (i.e., hyperactivity) has a strong impact on the affective disorders manifestation and is an additional risk factor for DD and suicidal thinking (Dwivedi, 2012; Giletta et al., 2015; O’Connor, Gartland, & O’Connor, 2020).

The World Health Organization (2013) suggests that women victims of IPV with a psychiatric diagnosis should receive specialized evidence-based treatments with health professionals trained on gender violence. For instance, in a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, Hameed et al. (2020) described the effectiveness of several psychological interventions (including Psychoeducation, Cognitive Behavior Therapies, Acceptance and Commitment, Mindfulness, Integrative Therapies), in reducing depression and anxiety in women experiencing IPV. The authors reported that all kinds of therapies based on five or more sessions, but no fewer, were effective in reducing depression, and anxiety to a lesser degree. Contrastingly, the meta-analysis made by Keynejad, Hanlon, and Howard (2020) found that psychological therapies for IPV women (without mentioning the kind) were significantly effective only in reducing anxiety. However, evidence of the effectiveness of specific interventions for IPV exposed women in improving other negatively affected factors, such as quality of life or social support, are scarce (Hameed et al., 2020).

At the National Institute of Psychiatry “Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz” (INPRFM, Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz) two different group-based psychotherapies, an adapted Interpersonal Therapy (IPT) and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), has been applied with gender perspective to women victims of IPV with a psychiatric diagnosis; but their efficacy has not been investigated.

The adapted version of IPT proposed by Biagini-Alarcón (2016), targets the empowerment of women. The theoretical framework of IPT is based on the therapeutic approach of Yalom’s group processes (Yalom, 1986). The IPT therapeutic process incorporates the recognition of current dysfunctional coping strategies for dealing with severe stress, to progressively improve the appropriate management of emotions. One of the outcomes of IPT is the recovery of ego and body limits that have been lost due to the violent relationship with the aggressor and also addresses the interpersonal conflicts with the partner (including anger towards the aggressor) and with the family, as well as the relationships with other members of the community. To achieve the beneficial therapeutic goals of IPT, Biagini-Alarcón (2016) and Biagini-Alarcón, Cerda-de la O, and Cerda-Molina (2020) recommended applying the intervention through 20 group sessions.

ACT was described by Hayes, Strosahl, and Wilson (2012) and Páez Blarrina and Gutiérrez Martínez (2012). In contrast to IPT, ACT targets psychological flexibility and the reduction of stress; it focuses on present-oriented training to cultivate a sense of conscious awareness by using metaphors and other practices such as Mindfulness. The theoretical principle of ACT is the acceptance of suffering as part of the human condition and the thought that many of our human reactions and emotions cannot be controlled, instead, they can be recognized and accepted. The theoretical principle of acceptance states that many of our human reactions cannot be controlled, instead, they can be recognized and accepted. Then, rather than staying into an emotional struggle, ACT teaches to redirect the efforts in acknowledging their own values. Although ACT can be individually applied, the intervention has been adapted to the IPV women by applying 12 grouped sessions (Reyes-Ortega & Vargas-Salinas, 2016; Vargas-Salinas & Reyes-Ortega, 2016; Biagini-Alarcón et al., 2020). Applied as brief intervention, ACT has been useful to different diseases (Ruiz et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018; Asplund et al., 2021) and also has been effective in reducing aggressiveness in male perpetrators of domestic violence. However, no evidence has found for their effectiveness in women victims of IPV with anxiety and depression.

Because most psychotherapies also intend to reduce people stress levels (e.g., Wynne et al., 2019), measuring the cortisol response to an acute stressor in IPV women might function as a biomarker of their efficacy in reducing anxiety and depression. For instance, in a recent meta-analysis, Fischer, Strawbridge, Vives, and Cleare (2017) found that only eight articles measured cortisol response to a variety of challenges, pre and post interventions (mostly based on Cognitive Behavioral Therapies) in people with depressive disorders. In most of the articles, those people with higher basal or post-challenge cortisol still have higher scores of depressions at the end of the intervention, whereas two of the articles did not report significant results. These findings agree with the literature supporting that the hyperactivity of the HPA axis is characteristic of women with DD (Heim et al., 2000). To date, no research has investigated whether the psychological interventions could change the reactivity to stress, together with an improvement in mental health and quality of life in women with experience of IPV.

Therefore, to contribute with the study of the efficacy of interventions specially applied to IPV victims, the aim of the present research was to compare the changes in depressive and anxious symptomatology, quality of life, and cortisol reactivity to a cognitive task (measured across four saliva samples) after two different theoretical psychological interventions, ACT or IPT, in women experiencing IPV, as well as to compare the changes as a function of the suicide thoughts (due to those women might be less likely to benefit from interventions). According to the literature, we expected a decrease in cortisol secretion, concurrent with a decrease in anxiety and depressive symptoms as well as an improvement in the general quality of life. We might expect greater changes in emotional symptomatology and cortisol reactivity with ACT, since it comprises mindfulness and attention regulation, in contrast with the long-lasting IPT, based on women’s empowerment and the understanding of interpersonal relationships.

METHOD

Design of the study/description of the sample

This was a longitudinal, comparative, and randomized clinical trial carried out at the Gender and Sexuality Clinic and Psychotherapy Department of the INPRFM, Mexico City, Mexico. At the time patients presented for treatment, they were invited to participate, if they met the inclusion criteria of being adult women receptors of intimate partner violence (current and within the last 12 months), and with psychiatric diagnosis of depressive and/or anxious disorders. Exclusion criteria included a diagnosis of psychotic disorders, intellectual disability, substance abuse, serious physical illness, pregnancy, using contraceptives, and current treatment with corticosteroids. Diagnoses were made by Psychiatrists at the Gender and Sexuality Clinic, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Version 5 (DSM-5, American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and IPV was assessed by completing the Intimate Partner Violence Questionnaire. All participants were explained the purposes of the study and were told that they had the right to finish the procedure at any time. The dates of recruitment and follow-up were from November 1, 2017, to September 30, 2019, estimated time for research. Of the 71 patients that provided the written informed consent and completed the initial assessments, only 50 (Table 1) finished the interventions and completed the post-assessments; therefore, only these women entered the statistical analyses.

Table 1 Demographic data of the participants. Data express the frequency and percentage, excepting for age expressed as mean, standard deviation of the mean (SD) and range

| Parameter | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | M = 45.68 SD = 10.47 (range 21-74) |

| Alcohol consumption | 8 (16%) |

| Smoke | 7 (14%) |

| Marital status | |

| Single/relationship | 6 (12%) |

| Married/Cohabiting | 33 (66%) |

| Divorced/Separated | 11 (22%) |

| Occupation | |

| Housewife | 30 (60%) |

| Formal employment | 6 (12%) |

| Informal employment1 | 9 (18%) |

| Student | 1 (2%) |

| Other | 4 (8%) |

| Education degree | |

| Elementary | 7 (14%) |

| Secondary | 18 (36%) |

| High School | 12 (24%) |

| Complete University | 5 (10%) |

| Incomplete University | 5 (10%) |

| Master’s degree | 3 (6%) |

1Job without social security.

Measurements

Intimate partner violence. We applied the Mexican scale of violence by the male partner against women (Valdéz-Santiago et al., 2006; α = .99). This is a 27-item scale that measures four types of violence (psychological, sexual, physical, and severe physical violence – where life is at risk) and their severity as: no violence, moderated violence, and severe violence. α = .89, for the present sample.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; validated by Jurado et al., 1998; α = .87). This is a 21-item scale ranging from 0 to 63 total score; the scale establishes 0-9 points as minimal or absent depression, 10-16 mild, 17-29 moderate, and > 29 severe. α = .88 for the present study. Of the 50 participants, 38% (n = 19) answered the item 9 about having thoughts of killing themselves; these patients were classified as having suicide risk.

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; validated by Robles, Varela, Jurado, & Páez, 2001; α = .83). The total score of this scale ranges from 0 to 63; the scale establishes 0-5 points as minimal or absent anxiety, 6-15 mild, 16-30 moderate, and > 30 severe, α = .93 for the present study.

World Health Organization (WHO) Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQOL-BREF; Whoqol Group, 1998; validated by Skevington, Lotfy, and O’Connell, 2004; α = .68 - .81). This 26-item scale measures four health domains: Physical (daily activities, energy, fatigue, etc.); Psychological (bodily image, positive, and negative feelings, etc.); Environment (financial resources, home environment, transport, etc.); Social relations (personal relationships, social support, and sexual activity). Each item has a 5-point Likert interval scale for responses (1 = very bad/completely unsatisfied; 3 = neither unsatisfied; neither satisfied; 5 = Very good/completely satisfied). In the present sample, the internal consistencies were: total scale α = .88; physical health α = .72; psychological health α = .73; environment α = .70; social relations α = .60.

Salivary Cortisol Measurements. Saliva samples were frozen, thawed, and centrifuged twice at 1500 g during 30 min at 4°C, recovering only the supernatants (Schultheiss, Dargel, & Rohde, 2003). We measured cortisol in duplicates by using ELISA technique (ENZO life sciences) and by following the manufacturer’s instructions. Cortisol concentrations were reported in pg/ml. Inter-assay and intra-assay coefficients were 9.8% and 7.1% respectively. Cortisol measurements were made at the Ethology Department of the INPRFM.

Procedure

By quota sampling, participants were enrolled and assigned randomly to receive ACT (12 sessions once a week) or IPT (20 sessions once a week). The assignment sequence was made by a researcher with no clinical participation in the trial and was double blind for participants as well as for the researchers who evaluated the results. Therapeutic groups were of no more than 12 participants and every session lasted an hour and a half. Interventions were applied by researchers trained and with expertise in the application of ACT and IPT with gender perspective. The number of sessions for each psychotherapy were based on the intervention manuals and previous literature, all delivered with gender perspective which makes them friendly to this population (Vargas-Salinas & Reyes-Ortega, 2016; Reyes-Ortega & Vargas-Salinas, 2016; Biagini-Alarcón et al., 2020).

Prior to the interventions, participants received instructions for the saliva sampling, such as brushing their teeth and not to eat, smoke, drink tea or coffee (only water), for at least two hours before the test. Patients donated a total of four saliva samples (2-3 ml), collected into new polypropylene tubes (15 ml). After participants completed a general information questionnaire (around 11:00, to avoid the increase in cortisol awakening response; Elzinga et al., 2008) they were asked to donate the first saliva sample (basal sample). After the collection of the first sample, participants were instructed to complete a brief IQ test (only as a challenge to promote the cortisol response, thus, this test did have not a statistical value) comprising 18 questions of verbal, mathematical, and abstract reasoning, in 10 timed minutes. After 15, 30, and 45 minutes of the test, we collected the second, third, and fourth saliva samples and finally the BDI, BAI, and WHOQOL-BREF questionnaires were completed. The procedure took about 60-70 minutes and was performed in groups of around 10-12 participants. Saliva samples were labeled with a code to ensure the confidentiality of the volunteer and immediately frozen and stored at -20°C until assayed. This procedure was repeated at the end of the interventions.

Statistical analysis

We used Generalized Estimating Equation Models (GEE), suitable and robust for data dependency, i.e, repeated sample design on the same subject (Pekár & Brabec, 2018). To analyze the changes in BDI, BAI, and WHOQOL-BREF we introduced in each model, the scores as dependent variables and as independent, we introduced the time pre and post intervention (Pre-T and Post-T), intervention (ACT or TIP), suicide risk (suicide risk and no suicide risk), and age (in years) as covariate. For cortisol reactivity, we performed two GEEs: one for pre and a second for post cortisol response. We included as dependent variable the cortisol concentration and as independent variables, the time of saliva collection samples (basal, 15, 30, and 45 minutes post- cognitive test), intervention (ACT or TIP), suicide risk (suicide risk and no suicide risk), and age (years) as covariate. Analyses were performed in SPSS version 22. We included the main and interaction effects, and used Bonferroni as a post-hoc test; significance was set at P ≤ .05.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Research and Ethic Committee of the INPRFM (Project Number SC19114.0) and was conducted in compliance with the declaration of Helsinki and the National Official Norms for Research with Human Beings (Secretaría de Salud, 2012). As compensation, patients were offered to receive their psychological and endocrine profile and were also offered to receive free further psychological assistance if needed.

RESULTS

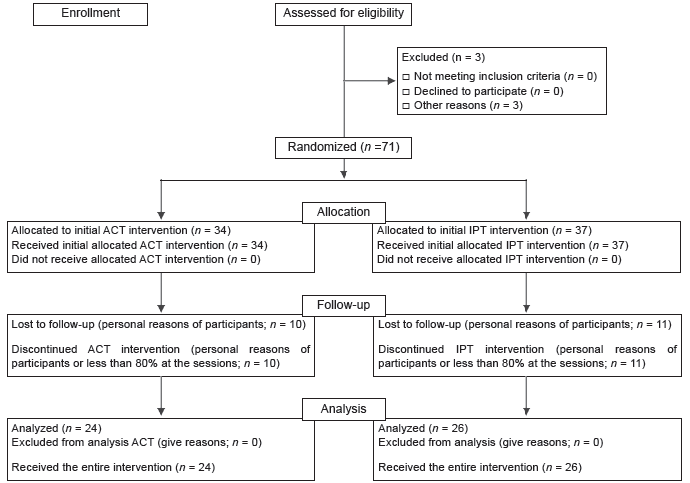

The flow diagram shows the number of randomized participants who started the interventions (74), those who dropped out (3), those who discontinued the intervention (22), and those who were included in the final analysis (50; Figure 1). There were no harms or unwanted effects in the groups.

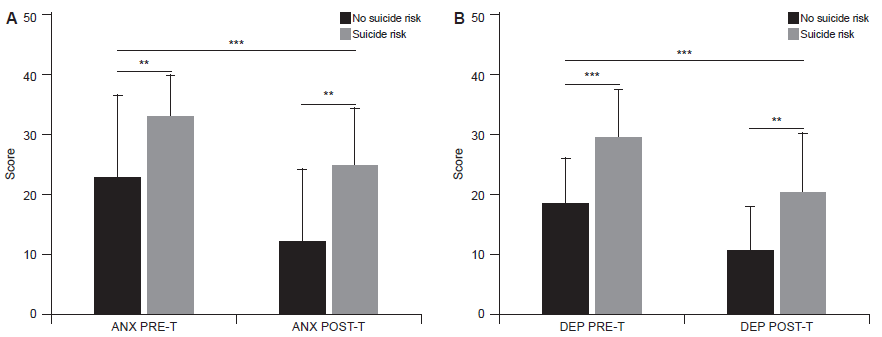

Anxiety symptoms varied with time, suicide risk, and age (X2 Wald = 40.38, df = 1, 50, p ≤ .001; X2 Wald = 19.63, df = 1, 50, p ≤ .001; X2 Wald = 9.59, df = 1, 50, p = .002, respectively). The interactions time × intervention and time × suicide risk were not significant (X2 Wald = 57.85, df = 1, 50, p = .06; X2 Wald = .24, df = 1, 50, p = .61). Anxiety symptoms decreased regardless of the type of psychotherapy and whether patients presented suicide risk (Cohen’s d = .79; 95% CI Pre-T = [22.80, 30.08] vs. Post-T = [13.80, 20.04]; Figure 2A). However, anxiety levels before and after the interventions were higher in patients with suicide risk (p = .002; Figure 2A). Anxiety symptoms decrease with age (Pearson r = -.28, n = 50, p = .04).

Figure 2 Anxiety and depression were higher in IPV exposed women with suicide risk before and after two types of interventions.A) Anxiety: ** p ≤ .01 no-suicide risk vs. suicide risk.B) Depression: *** p ≤ .001, ** p ≤ .01 no-suicide risk vs. suicide risk. Regardless of the type of intervention and the presence of suicide, anxiety and depression decrease after interventions *** p ≤ .001. Data expresses the mean (± SD).

Depression symptoms also changed significantly with time and suicide risk (X2 Wald = 40.19, df = 1, 50, p ≤ .001; X2 Wald = 24.72, df = 1, 50, p ≤ .001, respectively). Neither age nor the interactions time × intervention or time × suicide risk had significant effects (X2 Wald = .76, df = 1, 50, p = .38; X2 Wald = 1.94, df = 1, 50, p = .16; X2 Wald = .46, df = 1, 50, p = .49). Depressive symptoms decreased independently of the type of intervention and whether patients presented suicide risk (Cohen’s d = .85; 95% CI Pre-T = [19.58, 24.98] vs. Post-T = [11.54, 16.90]; Figure 2B). Nevertheless, mean depression levels were higher in patients with suicide risk (p ≤ .001 Pre-T; p = .008 Post-T; Figure 2B). After the interventions the number of patients with the suicide risk decreased from 19 to 10.

Table 2 shows a summary of the statistical analysis for the perception of quality of life. Time was significant for all dimensions, meaning an improved quality of life after interventions. Suicide risk was significant only for physical and psychological quality of life. Neither the interaction time × intervention nor the time × suicide risk were significant.

Table 2 Summary of the Generalized Estimated Equation models for the Quality-of-Life perception analyses before and after the interventions (X 2 Wald and β), as well as the mean, SD, and 95% CI of the Likert scale answer for each domain

| Quality of life | Physical | Psychological | Environment | Social |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | X2 Wald (β) | X2 Wald (β) | X2 Wald (β) | X2 Wald (β) |

| Time | 4.97 (.12)* | 23.03 (-.73)*** | 17.33 (-.54)*** | 16.93 (-.71)*** |

| Intervention | .03 (-.001) | .43 (-.25) | .44 (-.15) | .99 (-.32) |

| Suicide risk | 7.72 (.69)** | 10.40 (.46)*** | 1.26 (.04) | 1.69 (.04) |

| Age | .31 (-.05) | .42 (.004) | 1.54 (.008) | .003 (.00) |

| Time × T | .06 (-.62) | 2.60 (.31) | .77 (.13) | 3.68 (.39) |

| Time × suicide risk | 8.79 (.004) | .28 (.11) | 1.93 (.23) | 1.36 (.23) |

|

Mean (SD)

95% CI |

Mean (SD)

95% CI |

Mean (SD)

95% CI |

Mean (SD)

95% CI |

|

| Before T | 2.71 (.70) 2.51 - 2.91 |

2.45 (.73) 2.24 - 2.66 |

2.53 (.56) 2.37 - 2.70 |

1.51 (.57) 1.35 - 1.67 |

| After T | 2.93 (.76) 2.91 - 3.35 |

2.98 (.86) 2.69 - 3.19 |

2.87 (.65) 2.68 - 3.06 |

1.87 (.69) 1.67 - 2.07 |

| Cohen’s d | .57 | .66 | .56 | .56 |

Notes: T, intervention. In all cases df = 1. 50.

***p = .001;

** p = .01;

*p = .05.

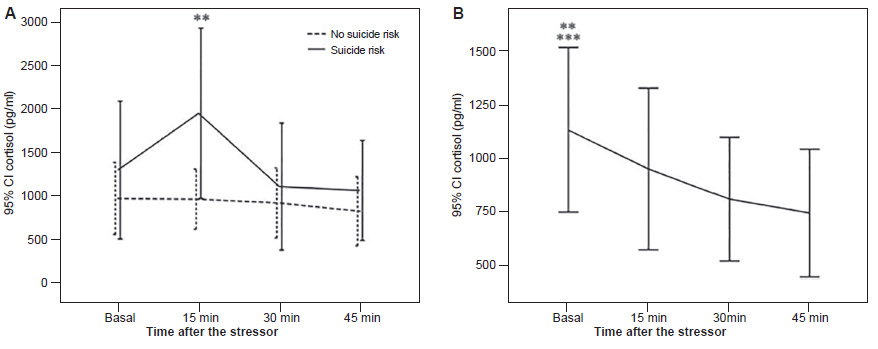

Before the interventions, cortisol secretion varied according to the time and the interaction time × suicide risk (X2 Wald = 13.28, df = 3, 197, p = .004; X2 Wald = 8.89, df = 4, 197, p = .03). Neither suicide risk alone nor the age affected cortisol secretion (X2 Wald = .53, df = 1, 197, p = .46; X2 Wald = .008, df = 1, 197, p = .93, respectively). As shown in Figure 3A patients with suicide risk, before the intervention, showed a significant rise in cortisol after 15 min of the cognitive test (p = .002 vs. basal) followed by a recovery after 30 min (p = .005 vs. 15 min). However, patients with no suicide risk showed a flattened profile without cortisol changes (p = 1.0). After the interventions, cortisol secretion varied only according to the time (X2 Wald = 21.97, df = 3, 197, p ≤ .001). The interactions time × intervention, time × previous suicide risk, and time × post suicide risk were not significant (X2 Wald = 7.31, df = 4, 197, p = .12; X2 Wald = 3.33, df = 4, 197, p = .34; X2 Wald = 4.08, df = 4, 197, p = .39). Figure 3B illustrates that after the psychotherapies, patients showed a significant decrease of cortisol (basal vs. 30 min p = .02; basal vs. 45 min, p≤ .001).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Our findings showed that regardless of the psychotherapeutic intervention ˗and duration˗, and the presence of suicide thoughts, a significant reduction in depressive and anxiety symptoms was observed in all patients, along with a decreased cortisol reactivity, pointing out the efficacy of both, ACT and IPT interventions. This result agrees with the findings of Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, and Lillis (2006), who described that there are not enough well-controlled studies to conclude that ACT be more effective than other active treatments. Moreover, our findings agree with that reported in the meta-analysis carried out by Hameed et al. (2020), who investigated the effectiveness of several psychological therapies for women experiencing IPV with depression as the main outcome and anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, and self-efficacy as secondary outcomes. In this meta-analysis, interventions were highly effective in reducing depression but less effective in reducing anxiety; besides, the duration of the treatments ranged between 5 and 50 sessions, concluding that interventions of less than five sessions were not very useful for the improvement of depressive symptoms. In our research, the number of sessions we delivered might have contributed to the beneficial effect of the interventions (12 for ACT and 20 for IPT). It is important to point out that although patients reduced their symptomatology, suicide risk women on average, turned from severe to moderate anxiety and depression, indicating the need to improve the therapies or to deliver a longer one, especially for women experiencing suicide thoughts. It would also be useful to evaluate for future research whether providing one type of psychotherapy versus another in less time generates some indirect impact on institutional costs, on the quality of the service provided, and in the burnout symptoms of the healthcare personnel who deliver the interventions.

We also found that anxiety scores decreased with age; this result could be explained by the fact that younger women suffered physical and sexual abuse more often and were exposed to greater risk to their lives than older victims as has been reported by Sarasua, Zubizarreta, Echeburúa, and del Corral (2007). The problem worsens because women of reproductive age (i.e., 19-30) are more vulnerable to developing anxiety disorders than adult or perimenopausal women (Terlizzi & Villarroel, 2020). Other explanations could be related to the fluctuations in reproductive hormones across the menstrual cycle (e.g., estradiol and progesterone). For instance, adult women with higher average progesterone levels across their cycles reported higher levels of anxiety than women with lower progesterone cycles, such as menopausal women (Reynolds et al., 2018). Moreover, greater estradiol increases have been correlated with negative mood in perimenopausal women (Gordon, Eisenlohr-Moul, Rubinow, Schrubbe, & Girdler, 2016). Steroid reproductive hormones also contribute to the regulation of some brain neurotransmitters such as serotonin or allopregnanolone, with potential role as anxiolytics, by promoting adaptive responses to stressors. Then, in cycling women the hormonal fluctuation along with altered cortisol response due to the IPV, might produce a reduced inhibitory tone or less efficient HPA axis stress regulation. Consequently, such altered hormonal regulation contributes to produce a women’s increased vulnerability to anxiety disorder development (Li & Graham, 2017).

In the present study we also evidenced the efficacy of ACT and IPT in the perception of quality of life in all its dimensions (physical, psychological, social relations, and environment). However, the perception of social life that was the most affected; for instance, we found that the score changed from worse to bad, highlighting the negative impact of IPV on women, and the need to reinforce the social strategies during the therapeutic processes. These findings agree with other authors that have not found a beneficial effect of psychological treatments in the social dimension of quality of life either (Hegarty et al., 2013; Tirado-Muñoz, Gilchrist, Lligoña, Gilbert, & Torrens, 2015). In this study, the slight improvement in the social and the other dimensions of the quality of life could be associated with the generation of friendship ties and cohesion of the psychotherapeutic group itself, which constitutes an emphatic and safe support (Yalom, 1986; Burlingame, Fuhriman, & Johnson, 2001). Nevertheless, that support was still not enough for the needs of women, since the social isolation derived from the partner violence limits their supportive network (Hansen, Eriksen, & Elklit, 2014; Morfín López & Sánchez-Loyo, 2015). Subsequent interventions would focus on identifying the factors that contribute to the modest improvement in the social dimension. We also found that the physical and psychological aspects of the quality of life (i.e., daily activities, energy, bodily image, positive and negative feelings) were worse in those women with suicide thoughts, which signals the importance of the negative impact of IPV in the health of women and the need of an early detection of the risk.

Regarding cortisol, we found an increased response in those women at suicide risk indicating that women with severe symptoms of anxiety and depression, a rapid activation of the HPA axis occurs, compared to the lack of response in women without the risk. It is known that the stress related to living in an adverse environment, such as those imposed by IPV, with limited resources and uncertainty about the future can place women at risk for multiple health problems, such as suicide risk (Sabri & Granger, 2018). Our findings agree with O’Connor et al. (2020) and O’Connor, Ferguson, Green, O’Carroll, and O’Connor (2016) describing an overview of studies revealing that a dysregulated HPA axis activity and cortisol levels, constitutes an additional risk factor for DD and suicide in people with susceptibility to such behavior. The higher cortisol response in women with severe symptoms and suicide thoughts might be also explained by the presence of a history of early traumas, since it has been reported that adult women in this condition are characterized by an HPA hyperactivity, probably due to CRH hypersecretion (Heim et al., 2000). Contrastingly, in the present research, women with moderate symptoms showed no response of cortisol probably reflecting a lack of positive emotions or hopelessness. At the end of the intervention, cortisol decreased after the cognitive test in all women, possibly indicating that both psychotherapies, ACT and IPT, helped women to manage the stress by reducing the stressful perception of the test. For instance, some studies have reported that hypo-responses (a reduced secretion) are characteristic of women with early adversities but without developing a psychiatric illness (Elzinga et al., 2008; Cerda-Molina, Borráz-León, Mayagoitia-Novales, & Gaspar del Río, 2018). Besides, the literature has suggested that a reduced cortisol secretion could be considered as a resilient response or a protection to the brain to avoid the negative effects of a prolonged cortisol exposure (e.g., cognitive decline or decreased neurogenesis; Wüst, Federenko, van Rossum, Koper, & Hellhammer, 2005).

Measures of the HPA axis activity, and in particular the levels of salivary cortisol have been considered as possible biological markers in psychological and epidemiological studies, as complement of the self-assessments of health (Fischer et al., 2017); however, there is still not enough evidence of the impact of psychotherapeutic interventions on such HPA axis responses. Several studies have analyzed the concentrations of cortisol in saliva or serum, of women with a history of IPV, however these measurements have been made in morning samples (cortisol awakening response) or at night, which are punctual measurements more linked to a metabolic effect of cortisol (Seedat, Stein, Kennedy, & Hauger, 2003; Basu, Levendosky, & Lonstein, 2013; Pinna, Johnson, & Delahanty, 2014). In the present study, we measured cortisol in response to a cognitive stressor before and after psychotherapies, as a marker of improved response to stress in women with a history of IPV, which has not been measured to date. The only reported study that measured cortisol reactivity in women with a history of any interpersonal violence was that of Morris et al. (2020), where they describe elevated cortisol concentrations in those women with current post-traumatic stress disorder, compared to those who did not present the disorder with a flattened response. Similar results were obtained in our research, where cortisol levels changed from a hyper-response to a hypo-response profile after the two therapeutic interventions, mainly in those patients with suicidal thoughts, which could be explained by an improvement in the body response to stress.

Summarizing, despite the small sample size, this study showed the efficacy of two different psychological interventions, ACT, a shorter therapy that targets psychological flexibility by using Mindfulness sessions, and IPT, a longer therapy based on empowerment and confrontation. Both interventions are appropriate candidates to improve the quality of life and mental health of women experiencing IPV. Besides, cortisol reactivity showed differences accordingly to the suicide thoughts; this measurement can be useful as a biomarker of the mental health risk in IPV women. Some interventions with ACT in other populations include reinforcing sessions (Asplund et al., 2021). However, future research is needed to investigate whether increasing ACT sessions could impact successfully in reaching the symptoms remission. Future research is also needed to early identify the predisposing and precipitating factors of women who suffer IPV and to design more specific interventions that allow to limit the suicide risk.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, the small sample size of women in both interventions due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which prevented us to continue with face-to-face group interventions; consequently, we might not make generalizations to other populations. Second, since the IPV scale was validated to measure the frequency and severity of cumulative violence acts during the last year, future research must include a scale that measures only recent IPV in order to analyze the impact of the intervention on women violence perception.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)