Introduction

In early December 2019, the emergence of a betacoronavirus, corresponding to an increase in the number of pneumonia cases in China, was reported. Most of those diagnosed reported having gone to a seafood market and purchasing various species of live animals as an exposure factor. The disease spread quickly locally, then to other parts of China, and subsequently globally (Dong et al., 2020; Gandhi, Lynch, & del Rio, 2020; Verity et al., 2020).

In early January 2020, this coronavirus was identified in samples from alveolar lavage fluid performed on patients diagnosed with pneumonia. It was subsequently identified by the China Center for Disease Control and Prevention as the disease causative agent. Days later, on January 7, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) provisionally named the new coronavirus 2019-nCoV. Afterwards, it renamed it SARS-CoV-2, which causes the COVID-19 disease (Cascella, Rajnik, Cuomo, Dulebohn, & Di Napoli, 2020; Dong et al., 2020; Verity et al., 2020).

COVID-19 has an incubation period of seven to 10 days, with its main symptoms being fever, cough, dyspnea, rhinorrhea, hypogeusia, anosmia, and, in some cases myalgia, headache, or odynophagia. In its most severe form, it is characterized by hyperinflammation, cytokine storm, and high cardiac injury biomarkers (Cascella et al., 2020; Dong et al., 2020; Verity et al., 2020). In Mexico, the first infected patient was reported on February 28, 2020 (Epidemic Stats, 2020).

For the prevention of COVID-19 infections, a number of behavioral measures have been established, such as social distancing (staying home, only going out for essential activities, avoiding crowds), individual protection and hygiene measures (hand washing, cleaning surfaces and objects), and social coexistence behaviors (sneezing into the crook of your arm, avoiding kissing, handshakes, and hugs) (Cascella et al., 2020; Holmes et al., 2020; Secretaría de Salud [SSa], 2020; Chater et al., 2020).

Based on these types of measures and in accordance with the Common Sense Model of Illness Perception (CSM) (Leventhal, Meyer, & Nerenz, 1980), engaging in these behaviors will depend on the way COVID-19 is perceived, the severity attributed to the disease, the experiences a person has had in relation to the disease, and the information available in the immediate context, as well as the perceived probability of becoming ill (Rubin, Potts, & Michie, 2010; Taylor, 2019).

Given the advances in it (Moss-Morris et al., 2002; Broadbent, Petrie, Main, & Weinman, 2006), the CSM (Leventhal et al., 1980), could help define the way people understand COVID-19. Although this process model makes it possible to understand the self-regulation of health and disease behavior in a global way (perception-behavior-results), its first stage (perceptual stage) considers a conceptual structure with various sub-dimensions that could shed light on the perception of COVID-19.

The dimensions constituting this stage are the cognitive and emotional perception of the disease, subdivided into (Broadbent et al., 2006; Leventhal et al., 1980; Moss-Morris et al., 2002): Identity: perceptual experience of the disease, type, place, and amount of symptoms or somatic sensations associated with it; temporality: perception of duration (acute, chronic, or cyclical); causes: perceived reasons of what caused the disease; consequences: perceived and experienced repercussions in various areas of life; personal control: perceived ability to control the disease; control of treatment: perceived impact treatment will have on the condition; coherence: clarity with which the disease is understood; and emotional perception: perception of emotional repercussions associated with the disease.

There are different forms of evaluation for the illness perception, such as drawings, unique items, and evaluation scales. For a detailed review, see Petrie and Weinman (2006), Petrie and Weinman (2012), Pacheco-Huergo et al. (2012), and Mora and McAndrew (2013).

Measurement scales include the Revised Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ-R, Moss-Morris et al., 2002), divided into three sections: 1. identity assessment; 2. scales of personal control, treatment control, acute/chronic temporality, cyclical course, consequences, emotional perception, and coherence; and 3. scale of causes. The IPQ-R was initially validated in patients with chronic diseases, although versions for infectious and acute diseases are now available (Figueiras & Alves, 2007; Hagger & Orbell, 2005; Wu et al., 2018). This instrument already has reliability and validity data in Mexico for patients with asthma (Lugo-González, Fernández-Vega, Pérez-Bautista, & Vega-Valero, 2020).

Another instrument is the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (BIPQ, Broadbent et al., 2006), which consists of nine items on the CSM sub-dimensions. Derived from this instrument, evaluations have been adapted and research data obtained in Spanish in the context of COVID-19 (Molero-Jurado, Herrera-Peco, Pérez-Fuentes, & Gázquez-Linares, 2020; Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2020).

Given that the COVID-19 pandemic is having emotional, social, and economic consequences worldwide (Brooks et al., 2020; Douglas, Katikireddi, Taulbut, McKee, & McCartney, 2020; Holmes et al., 2020; Lai et al., 2020; Pérez-Gay et al., 2020), it was considered pertinent to conduct an evaluation on the perception of COVID-19 in Mexican population using the IPQ-R already validated in this country. Accordingly, the objective of this study was to evaluate and compare the disease perception and the practice of prevention and exposure behaviors based on the severity and risk attributed to COVID-19 in Mexican adolescents and adults.

Method

Design

A descriptive, comparative study was conducted, based on the description by Méndez, Namihira, Moreno, and Sosa (2001).

Participants

Using chain or network samplings (Hernández-Sampieri, Fernández-Collado, & Baptista-Lucio, 2014), 1,560 adolescents and adults from various Mexican states with an average age of 31.88 years (SD = 11,045, Range = 15-77 years) were invited to participate voluntarily.

Instruments

Socio-demographic data card: Set of items to obtain information on residence, family, educational, occupational data, and use of information media, among others.

Revised Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ-R; Moss-Morris et al., 2002): Instrument to assess cognitive and emotional illness perception. The version validated in Mexico (Lugo-González et al., 2020) has evidence of reliability with Cronbach’s alpha and data with structural, convergent, and divergent validity. For this paper, the identity assessment was adapted with a list of 12 symptoms associated with COVID-19, as well as 16 items corresponding to the sub-dimensions of temporality, consequences, personal control, coherence and emotional perception (modifying the name of the disease). The scale has a four-point Likert-type response format ranging from totally disagree to totally agree. The reliability analysis showed a Cronbach’s alpha of .886 while the evidence of structural validity indicated a three-factor structure (emotional perception, consequences, and personal control) that explain 49.121% of the variance (KMO = .922, X2 = 10487.243, p < .01) with six items for the first factor, seven for the second and three for the third.

COVID-19 Preventive and Exposure Behavior Scale (PEBS-COVID19): Behavioral scale designed ad hoc for this study and based on the recommendations of the SSa (2020), comprising 11 items evaluating the frequency of preventive behaviors (hand washing, surface cleaning, hand-to-face contact, sneezing into the crook of your arm, and social distancing) and exposure (physical contact, handshaking, and greeting people with a kiss). The scale has a four-point Likert-type response format that goes from I always do it this way to I never do it this way. The reliability analysis showed a Cronbach’s alpha of .796 while the evidence of structural validity corroborated a bifactorial structure that explains 41.936 of the variance (KMO = .827, X2 = 5046.614, p < .01) with eight items for the first factor (prevention), and three for the second (exposure).

Assessment of perception of severity and risk: Items that assess the severity attributed to COVID-19, as well as the perceived risk of contracting the disease. Both items are answered on a four-point Likert-type scale ranging from totally disagree to totally agree.

Procedure

The evaluation was conducted on Google-Forms Online® and distributed through email and social networks such as Facebook® and WhatsApp® from March 22 to April 4, the week all educational centers in Mexico closed and one day before the official start of the National Healthy Distance Day (SSa, 2020). This evaluation was active during the last week of phase 1 and the first week of phase 2 of the COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico.

Statistical analysis

The statistical program SPSS version 24 for Windows was used. Data normality analyses were conducted to determine the type of statistic to use for the purposes of comparing the variables. Given the sample size and the analysis program, the Shapiro-Wilk (W) test was used, based on the recommendations of Pedrosa, Juarros-Basterretxea, Robles-Fernández, Basteiro, and García-Cueto (2015). Subsequently, descriptive statistics calculations (measures of dispersion and central tendency) were carried out for the sociodemographic variables, perception of COVID-19, prevention and exposure behaviors, and perceived severity and risk.

The comparative analysis was carried out by constructing categorical variables of

severity (severe/non-severe) and risk perception (risk/non-risk) and using the

Mann-Whitney U statistical test, considering a p < .05 for significant

differences between groups. Effect size (Rosenthal’s r) was calculated

with the following cut-off points: small effect (.1 to < .3); moderate effect (.3 to

< .5); and large effect (≥ .5) (Cohen, 1988),

using the following equation: (

Ethical considerations

Participants could answer the form after they had given their informed consent. The project was evaluated and accepted by the research ethics committee of the Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Respiratorias (INER), with the following registration number assigned by the committee: S02-20.

Results

Descriptive analysis

Data in the normality tests showed that none of the variables included behaved in a normal way, since the values in the various sub-dimensions of disease perception ranged from W = .860 to .976 (gl = 1560; p < .01 ) and the values of prevention behaviors from W = .894 to .968 (gl = 1560; p < .01), while the value of perception of severity was W = .873 (gl = 1560; p < .01) and risk perception was W = .964 (gl = 1560; p < .01).

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants, where it is observed that they were mostly women (75%), residents of Mexico City and the State of Mexico (73.7%), single (37.5%), and had completed higher education (80.9%).

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

| Variables | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1,176 | 75.4 |

| Male | 384 | 24.6 |

| Place of residence | ||

| Mexico City | 597 | 38.3 |

| State of Mexico | 553 | 35.4 |

| Other states | 410 | 26.3 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 885 | 37.5 |

| Married | 340 | 31.1 |

| Partnered | 239 | 15.3 |

| Other | 96 | 16.1 |

| Educational level | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 1106 | 70.9 |

| High school | 207 | 13.3 |

| Graduate | 156 | 10 |

| Other | 91 | 5.8 |

Table 2 shows the descriptive data of the participants in terms of perception of COVID-19, the self-report on preventive and exposure behaviors and severity and perceived risk.

Table 2 Descriptive results of perception of COVID-19, preventive and exposure risks and severity and perceived risk

| Instrument | Subdimension | Mdn | IR | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPQ-R-COVID19 | Identity | 7 | 3 | 0 | 12 |

| Consequences | 20 | 5 | 7 | 28 | |

| Personal control | 9 | 3 | 3 | 12 | |

| Emotional perception | 14 | 7 | 6 | 24 | |

| PEBS-COVID19 | Preventive behaviors | 25 | 6 | 8 | 32 |

| Exposure behaviors | 6 | 4 | 3 | 12 | |

| Severity | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |

| Risk | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

Note: Mdn: Median; IR: Interquartile range.

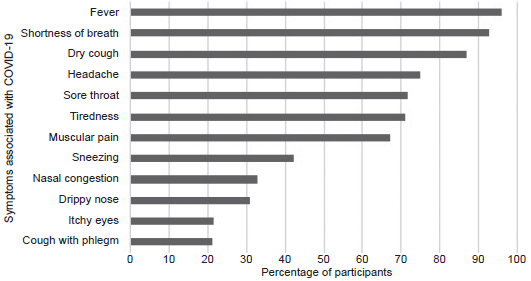

The results show that seven of the 12 main symptoms associated with COVID-19 (fever, dyspnea, dry cough, headache, sore throat, tiredness, and muscle and joint pain) show a positive identification in over 50% of participants. Conversely, the symptoms that were identified to a lesser extent by participants were: sneezing, nasal congestion, runny nose, itchy eyes, and cough with phlegm ( Figure 1).

It can also be seen that one of the main concerns of participants is the impact (perceived) the disease will have given the time it will last, the difficulty of understanding and controlling it, and the effect on people’s lives, the family, the economy, and emotional stability (sub-dimension of consequences). This last aspect is shown in the emotional perception sub-dimension, where the impact of COVID-19 is reported in experiences of worry, anxiety, anger, and mood changes.

Despite the emotional impact and perceived consequences of COVID-19, participants reported a high perception of personal control to avoid contracting the disease, which apparently coincides with the high self-report of preventive behavior (hand washing, social distancing, protection at home, sneezing into your elbow, and avoiding touching your face) and low exposure behavior (shaking hands and/or kissing, and hugging others).

Finally, the data on severity and perceived risk show that in general, participants regard COVID-19 as a serious disease, yet do not consider themselves at risk of becoming ill.

Comparative analyses

Once the severity and risk categories had been constructed, 946 participants were located who declared that COVID-19 was a serious disease and 614 that it was not (Table 3). Likewise, 437 perceived themselves as being at risk of becoming ill with COVID-19 while 1123 did not (Table 4).

Table 3 Comparison of perception of COVID-19 and preventive behaviors between severe and non-severe categories

|

Severe

(n = 946) |

Not severe

(n = 614) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument | Contrast | Mdn | IR | Mdn | IR | U | Z | p | r | |

| IPQ-R-COVID19 | Identity | 7 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 282864.000 | -.879 | .379 | .02 | |

| Consequences | 20 | 5 | 18 | 7 | 172306.000 | -13.634 | .000 | .34 | ||

| Personal control | 10 | 2 | 9 | 4 | 208348.000 | -9.565 | .000 | .24 | ||

| Emotional perception | 16 | 5 | 12 | 7 | 179794.000 | -12.754 | .000 | .32 | ||

| PEBS-COVID19 | Preventive behaviors | 25 | 6 | 25 | 7 | 272417.000 | -2.076 | .038 | .05 | |

| Exposure behaviors | 6 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 264961.000 | -2.953 | .003 | .07 | ||

Note: Mdn: Median; IR: Interquartile Range; r: Effect size Rosenthal’s r.

Table 4 Comparison of perception of COVID-19 and preventive behaviors between categories of perceived and non-perceived risk

|

Severe

(n = 437) |

Not severe

(n = 1123) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument | Contrast | Mdn | IR | Mdn | IR | U | Z | p | r | |

| IPQ-R-COVID19 | Identity | 7 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 235909.000 | -1.198 | .231 | .0 | |

| Consequences | 21 | 4 | 19 | 5 | 162841.000 | -10.364 | .000 | .26 | ||

| Personal control | 9 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 229766.000 | -1.979 | .431 | .05 | ||

| Emotional perception | 16 | 5 | 13 | 7 | 165727.500 | -9.989 | .000 | .25 | ||

| PEBS-COVID19 | Preventive behaviors | 25 | 6 | 25 | 6 | 242189.000 | -.400 | .689 | .01 | |

| Exposure behaviors | 6 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 221787.000 | -2.967 | .003 | .07 | ||

Note: Mdn: Median; IR: Interquartile range; r: Effect size Rosenthal’s r.

A comparison between severe/non-severe and the sub-dimensions of perception of COVID-19 showed that those who consider the disease serious perceive greater consequences (Mdn = 20) and are more emotionally affected (Mdn = 16) than those who do not consider it serious (Mdn = 18 and Mdn = 12, respectively). In fact, this assessment of severity has a moderate effect on the perception of consequences and emotional effects (r = .34 and r = .32, respectively).

However, perceiving COVID-19 as a serious disease also fosters a greater perception of personal control (Mdn = 10) to avoid getting the disease, although the effect is small (r = .24).

Regarding preventive behaviors, it was observed that those who consider it serious engage in this type of behaviors more frequently, compared to those who do not regard it as serious. Despite this, the effect of the perception of severity on preventive behaviors has only a small effect. A similar result was found in exposure behaviors, where those who perceive COVID-19 as not serious engage in this type of behavior more frequently.

Regarding perceived risk, it was found that those who consider themselves to be at risk of becoming ill from COVID-19 perceive greater consequences (Mdn = 21) and are emotionally more affected (Mdn = 16) than those who do not perceive themselves to be at risk (Mdn = 19 and Mdn = 13, respectively); although the effect is small (r = .26 and r = .25, respectively).

In much the same way as in the severity assessment, in perceived risk it is found that those who do not perceive themselves at risk of becoming ill from COVID-19 engage in exposure behaviors more frequently (Mdn = 7), also with a very small effect (r = .07).

Discussion and conclusion

The results found that participants identified the 12 COVID-19 symptoms on the list although, in general, they identified seven of them more often. This is striking since, on the one hand, the latter are the most frequently reported ones in the medical literature (Gandhi et al., 2020) and the ones most widely disseminated in the media and official sources (SSa, 2020), which could reflect the general contact of participants with various sources of information on COVID-19. In fact, regardless of the severity and attributed risk, identification of symptoms is similar between groups.

At the same time, when having to discriminate between such a wide range of symptoms, there could be confusion over their importance or a minimization of their severity, as noted by Lunn et al. (2020), especially if it is mistakenly thought that COVID-19 symptoms are similar to those of the common cold and range from mild to moderate (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [NIAID], 2020).

However, the duration of the pandemic and the economic and social consequences appear to be two of the elements that most concern participants. It should be recalled that in Mexico, mitigation measures began ahead of time to ensure that transmission took place gradually, which meant that an extension was planned for the length of time of social distancing and the return to normality (SSa, 2020).

In this context, various emotional consequences would undoubtedly be expected in the population, since these occur after a prolonged time of social distancing, as shown by the findings during the outbreaks of the SARS virus in 2003 (Cava, Fay, Beanlands, McCay, & Wignall, 2005; Day, Park, Madras, Gumel, & Wu, 2006) and of COVID-19 in Spain (Sandín, Valiente, García-Escalera, & Chorot, 2020) and China (Dai, Hu, Xiong, Qiu, & Yuan, 2020; Wang et al., 2020).

The emotional perception results indicate that a significant number of participants were experiencing emotional sequelae, although the general data show they were only moderately impacted. This could be attributed to the moment of data collection (phase 1 and phase 2), meaning that a set of expected psychological responses is involved, which coincides with the study by Wang et al. (2020) during the initial phase of COVID-19 in China, El Salvador (Orellana & Orellana, 2020), and Mexico (González Ramírez, Martínez Arriaga, Hernández-Gonzalez, & De la Roca-Chiapas, 2020).

The evaluation of consequences, the emotional impact, and risk perception are expected to evolve to more adverse scenarios, as has been the case in Mexico and other parts of the world in the H1N1 influenza in 2009 (Rubin, Amlôt, Page, & Wessely, 2009; Rubin et al., 2010), the Ebola outbreak in 2014 (Garfin, Silver, & Holman, 2020), the MERS outbreak in 2015 (Yang & Cho, 2017), and during COVID-19 (Muñiz & Corduneanu, 2020).

It is worth noting that despite the negative experiences and perceptions at an emotional level experienced by participants, a high perception of personal control over preventing the spread of COVID-19 was also expressed. This variable should also be considered, since it is causally linked to preventive behaviors during the pandemic and the prevention of emotional sequelae (Bashirian et al., 2020; Shacham et al., 2020).

Regarding prevention and exposure behaviors, it was found that the vast majority reported engaging in preventive and protective behaviors. Conversely, they declared that they continued to engage in exposure behaviors such as shaking hands, kissing, and hugging other people to a lesser extent. This is striking since the vast majority did not consider themselves to be at risk of becoming infected with COVID-19 (n = 1123). This low risk perception is a determinant for failing to engage in preventive behaviors during COVID-19 and other pandemics (Rubin et al., 2010; Urzúa, Vera-Villarroel, Caqueo-Urízar, & Polanco-Carrasco, 2020). For this reason, desirable responses in social terms should not be ignored, since, where protective and adherence behaviors are concerned, self-reporting of the latter tends to be overestimated (Stirratt et al., 2015).

In this respect, there is an undeniable need to encourage the maintenance of preventive behaviors throughout the pandemic. It is therefore essential to implement behavioral programs that will inform, increase the perception of severity and risk, and model, shape and reinforce preventive behaviors, guaranteeing their morphological correspondence and a functional environment to implement them and identify contingent positive results (Chater et al., 2020; Lunn et al., 2020; Urzúa et al., 2020; West, Michie, Rubin, & Amlôt, 2020).

Limitations of the study include the fact that the evaluation was conducted at a distance, including socially valued responses. Despite this, Stirratt et al. (2015) have widely recommended distance evaluations through the Internet, so that the interviewer or administrator does not influence the participant’s answers. In fact, Pérez-Bautista and Lugo-González (2017) showed that there are no statistically significant differences in the answers regarding protective behaviors between participants who answer instruments using pencil and paper and via Google® form.

In addition to the above, due to the fact that the sampling was non-probabilistic, there could be problems regarding the sample distribution, since, in the present study, most respondents were single women, from the center of the country, and with a high educational level. However, it suffices to review the sample distribution and characteristics of the participants in current research on COVID-19 to see that these data are consistent in various parts of the world, with women’s responses ranging from 52% to 80% (Dai et al., 2020; González Ramírez et al., 2020; Molero-Jurado et al., 2020; Muñiz & Corduneanu, 2020; Orellana & Orellana, 2020; Shacham et al., 2020).

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)