Introduction

Codex Yanhuitlan is a manuscript that takes its name from the town of origin in the Mixteca Alta, in the modern state of Oaxaca. The main portion of the document is currently held in the Biblioteca Lafragua (henceforth Lafragua) in the city of Puebla. Since the landmark publication by Jiménez Moreno and Mateos Higuera of this part of the manuscript, numerous other studies have added both pages and historical information to this important document that relates the early history of the town (ñuu in Mixtec) and cacicazgo (yuhui tayu) of Yanhuitlan.1 Berlin identified a few pages in the Archivo General de la Nación (henceforth AGN), where they are annexed to a late colonial lawsuit from the Mixteca de la Costa. Sepúlveda y Herrera published both Lafragua and AGN sections, adding her own historical and codicological analysis.2 Jansen and Pérez (2009) proposed a new comprehensive interpretation, based also on the identification of a few more pages, -copied in an -unpublished work by Oaxacan historian Manuel Martínez Gracida.3 Those very same pages were finally retrieved in the early 2000s and are now part of the collection of the Centro Cultural Santo Domingo (henceforth CCSD). Doesburg, Hermann, and Oudijk released the latest publication, which includes original observations and interpretations, and a colored reproduction of all three now known parts.4

Our proposed analysis offers new insights by focusing on two relatively disregarded aspects of this complex manuscript, namely its material and stylistic components. Historians, such as Jiménez Moreno and Doesburg and colleagues, and iconographers such as Jansen and Pérez Jiménez gave an overall picture of the content and historical context of the document. By attending to specific codicological and stylistic features, we ask new questions and propose different interpretations. We suggest that Codex Yanhuitlan was modified on several occasions, purposefully adding and erasing information, perhaps even expressing competing views on the early colonial political, economic, and religious adjustments in town. Its final and complete dismemberment, which most likely occurred a few centuries after its creation, further hampers a comprehensive interpretation of its intended contents and agenda.

Codex Yanhuitlan was created roughly one generation after the Spanish conquest of the Mixteca Alta and combines Mixtec iconography and conventions with imported Western representational and artistic canons. It is painted on European paper following a technique known in the art historical literature as grisaille, a term borrowed from French, which literally means “grey-colored.” The ink employed is mostly iron-gall, generally considered a post-conquest material, which has now turned from its original black to a brown or yellow color. The manuscript, which was perhaps never bound, follows the typical pagination of a European-style book. Due to its tumultuous afterlife, however, all of its pages are currently loose and the original ordering can only be reconstructed based on the dates present on a few pages and the internal logic of the pictorial narrative. As it stands today, the three parts of Codex Yanhuitlan do not constitute a complete manuscript. Small and seemingly unrelated fragments of the Lafragua section clearly indicate that whole pages are still missing. Overall, the document deals with the colonial yuhui tayu (cacicazgo) of Yanhuitlan and tribute payment, while also devoting many of its extant pages to the Dominican evangelical enterprise in the Mixteca, as well as depictions of Mesoamerican gods.

Paper, Quires, and Watermarks

The support of Codex Yanhuitlan contains some revealing clues to the structure of the document as a whole. Paper in the early modern world was produced in single large sheets, laid out in wet paper mulch over a screen made up of thin, closely spaced metal wires in one direction and thicker, more widely spaced metal wires in the other direction. On the paper surface, these metal wires left imprints. The thin, closely spaced lines are called wire or laid lines and the thicker, wide-spaced lines are chain lines. Watermarks, which were also laid on the wire, are designs made by metal wires that were attached to the chain lines, leaving a maker’s mark on the paper. Often each papermaker had multiple sieves in use at the same time and although the watermarks may have had the same design, each was unique because they were handcrafted individually. This also goes for chain and wire lines, which leave a distinctive and unique pattern on each sheet of paper coming from a mold.

Before the establishment of the first paper mill in Culhuacan in 1575, all paper in the Americas was imported from Europe, as was the case for the paper on which Codex Yanhuitlan was made.5 Medieval and early modern European paper was produced and traded in the form of quires, i.e. multiple sheets stacked together and folded as a booklet, rather than in loose sheets.6 Without the use of the ring binder, binding loose sheets together to form a book is almost impossible, so the production of paper in a quire was essential for the creation of a book. The current state of Codex Yanhuitlan as loose sheets of paper is the result of deterioration on the edges that were left exposed when the document was disassembled to be reused and presented as evidence in court cases, roughly two hundred years after its execution.7 Despite these deteriorated edges, it is possible to reconstruct some of the original sheets, before they were physically separated.

The watermarks on Codex Yanhuitlan sheets (fig. 1a) are common in early colonial documents.8 One is of a pilgrim, which places the location of production in southern Europe, most likely Catalonia or Italy.9 The second type of watermark is also a pilgrim with a slightly different hat, no letters, and attached in a different position to the chain lines. This watermark is only found on one page, Lafragua 12. The third watermark, a hand with extended fingers, was used over a wide area from the Italian piedmont to southern France.10 This watermark is found in two different variations, exclusively in AGN 504 and 507. Furthermore, the paper of these pages appears to be different.11 The largest portion of the Codex Yanhuitlan, including both Lafragua and CCSD sections, has the exact same watermark. This indicates, preliminarily, that some pages may have been conceived separately and a different moment.

A paper mold often has one watermark, placed off-center. When a single sheet is folded in two (called bifolio) to make a quire the size of Codex Yanhuitlan (ca. 21.6 × 33 cm), one folio presents a watermark, while the other is blank. Stacking a series of such sheets creates a quire in which on one side all pages contain a watermark, while on the other side no watermarks are visible (fig. 1b). In the final book, composed of multiple quires next to one another, one would thus have alternating sections of pages with and without watermarks. Only in the middle of each quire, would there be one whole bifolio, with a watermark on one side. It seems plausible that Codex Yanhuitlan was drafted and preserved in quires, probably sown together to make a single book, until the eighteenth century, when it was reused in a series of lawsuits. All CCSD pages have the same watermark indicating that they not only belong to the same half quire, but were cut from it, a fact that reinforces the hypothesis that the current and complete dismemberment of the manuscript is due to a much later reuse in a seemingly unrelated lawsuit. Contentwise, these pages illustrate -several large and luxury objects (a shield, a feather cape, two trumpets) together with a narrative scene that includes two male -walking characters in the center.

1. a. Watermarks of Codex Yanhuitlan; b. Folios and quires with watermarks and wires. Drawing by Ludo Snijders.

The AGN pages, which were also cut and repurposed in a different late colonial lawsuit, on the other hand, contain depictions of Mesoamerican gods and pre-Hispanic luxury items together with a narrative scene of two male characters. As such, both CCSD and AGN sections contain one page with human figures combined with year glyphs, while the rest depicts items with a clear precolonial iconography, luxury items, such as feather-work and jewelry. In fact, aside from those pages there is little in the document that refers to pre-conquest times. This suggests that at the time when the two parts of Codex Yanhuitlan were separated to accompany a lawsuit, early colonial events therein depicted were recalled as proof of wealth to further claims of antiquity and legitimacy.

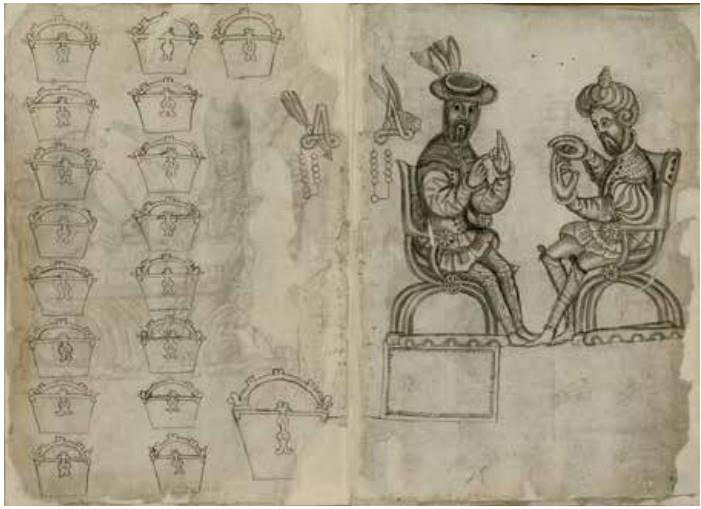

The fact that every single page has been purposefully cut has generated a persistent problem in the reconstruction of the reading order and narrative progression. A closer look reveals that some pages should be read as part of a larger scene rather than single and discrete depictions. For example, Lafragua 4r and 6v (fig. 2) have been previously related in terms of contents.12 On Lafragua 4r, two Spaniards, presumably the encomendero of Yanhuitlan, Francisco de las Casas, on the left, and a Crown-appointed corregidor to the right, are facing one another, engaged in a lively gestural conversation. The meeting is said to have occurred in the year 11 Rabbit. The following year, 12 Flint, is depicted on Lafragua 6v, along with eighteen metal buckets, a fact that has been interpreted as the gold tribute the two Spanish officials may have been arguing about. When the two pages are placed next to each other, as seen in figure 2, not only are the two dates neatly displayed on the same height right next to each other, but one thin line can be seen going through the pages and connecting the two scenes, from the square representing the toponym of Yanhuitlan on Lafragua 4r, to the largest bucket of gold on the other page. Placed in this manner, the page with the later date (12 Flint) is to the left of the page with the earlier date (11 Rabbit), suggesting therefore a reading order from right to left. While it is normally assumed that the reading proceeds from left to right as one would expect in a European book, Codex Yanhuitlan offers no internal evidence that this was necessarily the case. The content of the manuscript is developed fully in pictograms. Mesoamerican writing systems in general do not have a preference regarding the reading order, which often proceeds in boustrophedon fashion over a single page. Books and manuscripts were not bound in ancient Mesoamerica, rather the contents could flow easily through a long and interrupted surface, folded in an accordion fashion. Scenes could expand and contract according to the painter’s will or the story’s requirements. The use of the two facing pages as a single spread is consistent with a pictographic approach to manuscript production.

2. Two Spaniards engaged in a discussion, possibly about the tribute of gold. Lafragua 6v and 4r, proposed reconstruction based on the fading line connecting the metal bucket (left) and the toponym of Yanhuitlan (right). Codex Yanhuitlan (C.B. 86922-41010404), Biblioteca Histórica José María Lafragua de la Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Mexico.

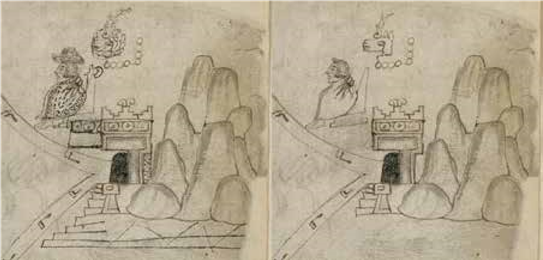

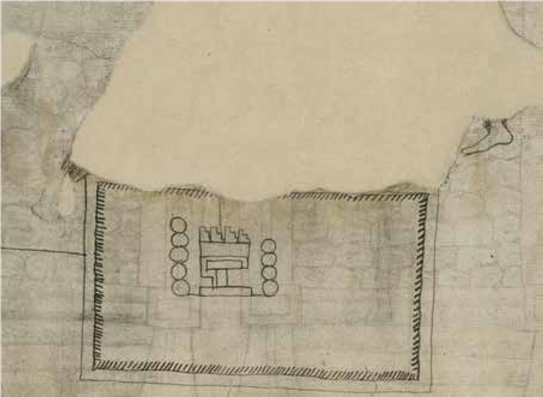

Considering the sheets not individually, but rather as part of a two-page spread allow for further interesting observations. Jansen and Pérez Jiménez and Doesburg and colleagues relate CCSD 1v and Lafragua 9r, because they both contain a depiction of plots of land and crops.13 The reverse of Lafragua 9 (fig. 3, left) depicts a church, on top of the Yanhuitlan toponym, surrounded by damaged place glyphs, possibly Yanhuitlan’s boundary markers.14 On the right, a chair is clearly depicted, although the person who was seated on it was deliberately effaced. The seated person on the right is located in such a way that he would have to stare beyond the edge of the page, suggesting that this was originally not the end of the scene, but rather the middle of a two-page scene. A similar situation occurs on page CCSD 1r (fig. 3, right), reverse of CCSD 1v, where all figures seem to look at something on the left, while the top, right and bottom of the page is bordered by hills and rivers. When placed next to each other, Lafragua 9v and CCSD 1r (fig. 3) create a sort of map of the area where the church was built and where the resources assigned for its construction and maintenance were located. This is the same interpretation given previously for this portion of the codex, with the difference that the visually connecting element is the map, framed by the different types of crops. In our proposed interpretation, the two dates on CCSD 1v would correspond to two moments. First, the donation of resources on the right of the page spread, where the two nobles and dignitaries are depicted (one is wearing sandals, signaling his status as a yya), in a maize field, eventually followed by the actual construction under the order of the cacique seated on the throne in Lafragua 9v. The dates given on CCSD 1r also contains another indication that the reading may have proceeded from right to the left because the later year glyph (9 House) is to the left of the earlier date (8 Flint). Finally, following the same line of reasoning, Lafragua 5, taken to be the first page of the manuscript, is better understood with a reversed reading of the page order. The battle of Tenochtitlan, on what is now the reverse of the page (5v), is an historical and political event that antecedes the cabildo meeting at Yanhuitlan in the obverse, and as such it is reasonable to assume that it should be presented earlier.

Another peculiar aspect characterizes Mixtec year signs throughout Codex Yanhuitlan. Dates span between years 1 Flint (c. 1520) and 12 Flint (c. 1544), but are irregularly placed. As previously remarked, they appear in groups of two, and in three instances (AGN 506, CCSD 1 and 2), two dates appear on the same folio, on either the same page or on both sides.15 Often, they do not seem to space and order events, but rather closely follow one another as if to suggest a reading order. Particularly telling is the case of CCSD 2. Year 9 Flint appears on one side of the folio together with a shield, while on the other side the following year, 10 House, accompanies the depiction of two serpentine scepters. While Jansen and Pérez Jiménez and Doesburg and colleagues agree that the objects may have been part of a dowry or wedding gifts for local Yanhuitlan leaders, the question remains why were the same set of gifts presumably donated during two different years and not at the moment when the wedding took place.16 The same observation applies to CCSD 1r (fig. 3, right), just discussed, in which two consecutive years are related to the donation of a plot of land.17 Also, as just seen, the connecting line in Lafragua 4r and 6v (fig. 2) seemingly indicates that the same event is depicted, and not two separate ones, through the course of two years. Although it would be too speculative to interpret the decision of such unusual date placement, the idea that dates may have played a different role rather than chronological marker should be taken into consideration. Perhaps dates were used to clearly establish and signal the reading order, which if it was indeed from right to left, may have required guidance and clarification to the reader.

3. A scene in Yanhuitlan including two male characters on the right and the town’s church on the left surrounded by several toponyms. Proposed reconstruction. Códice de Yanhuitlán, Centro Cultural Santo Domingo, Biblioteca Francisco de Burgoa, Oaxaca. Left: 9v; Biblioteca Histórica José María Lafruaga de la Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Méixco. Right: 1r.

Finally, Lafragua 3r contains the latest date recorded on the extant pages, day 1 Jaguar, year 12 Flint (ca. 1544). We argue that it may not in fact be the very last page. If the right to left order we propose is followed and we consider this to be the last page that has survived, it would be the right-hand part of a bifolio. This would explain why the church is depicted off-center on the page. It could also harmonize the dates given throughout the document, because, as it stands now, year 12 Flint is the only date that is not paired. If it was actually part of a larger scene, it may be that the other half of the scene contained the date 13 House, ca. 1545.

Unlike any known European-bound manuscripts from early colonial New Spain, Codex Yanhuitlan barely has any glosses and they all seem to have been added in the eighteenth century, when the document was divided in at least three parts and reused in several court cases.18 This is at odds with the contents, style, support and format of the manuscript that display a full awareness and absorption of Western artistic canons and techniques. If the reading order was indeed reverse, the near absence of Spanish glosses when the manuscript was initially drafted could be further explained, because the left-to-right progression of the Latin alphabetic script would have been at odds with the chosen right-to-left order. The proposed reversed reading and consequent placement of the dates generate a consistent, if odd, occurrence of the year glyphs. They not only appear in pairs, but also one right after the other on opposite pages. These are: years 1 Flint-2 House (1520-1521) on Lafragua 5r and 11r; years 5 Flint-6 House (1524-1525) on the two sides of AGN 506; years 9 Flint-10 House (1528-1529) on the two sides of CCSD 2; years 11 Rabbit-12 Reed (1530-1531) on Lafragua 4r and 15r. The consistent pattern goes against a straightforward reading of the dates as mere chronological markers and rather suggests that they meant to indicate something else. The fact that all three sections of Codex -Yanhuitlan are today composed of loose pages further corroborates the idea that when composed in quires the codex was meant to be read from right to left. In the context of a late-colonial reuse, the reverse reading would have caused even a greater deal of confusion and perhaps even hampered the case the litigating party was trying to make, and thus it was completely disassembled.

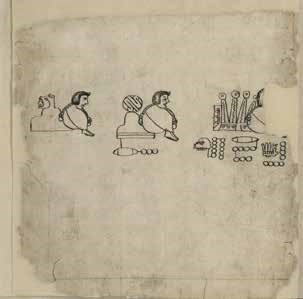

The AGN section of Codex Yanhuitlan was made using a different paper, as previously remarked.19 Two watermarks are only encountered here, as well, both in the shape of a hand, a very common watermark during the early colonial period in New Spain, as noted above. While it is in itself no surprise to find this type of watermark, the fact that it corresponds to a separate section of the manuscript may indicate that these pages were drafted separately from the beginning. At the same time, their painting style corresponds to that of the largest part of the codex (Lafragua section). The AGN pages are unique in that they depict four Mesoamerican gods on folios 504r-v and 507 (fig. 4). Two of them, Xipe and a solar deity, are represented in medallions, while two more are depicted as full figures interacting with one another. These contents are clearly at odds with the rest of the manuscript, that narrates historical events, and it is more akin to the religious manuscripts produced within the conventual schools, such as Codex Telleriano-Remensis, Sahagún’s Primeros memoriales and Historial general, and Durán’s Historia. Unlike all these examples, however, a specific historical narrative is embedded in the depiction of the veintena’s gods in Codex Yanhuitlan. On AGN 506v (fig. 4, far right) a Spanish -person sits on a chair facing a visibly smaller indigenous person who is also seated. The meeting is said to take place in year 5 Flint. If we start the section with this page, reading from right to left, the next page is 506r that displays a giant earth being or cave, accompanied by the date year 6 House, following 5 Flint. Its placement on the right side of a bifolio, allows to read it as a place setting for an action portrayed on the following left side. The association of the cave with the realm of the gods is well established for Mesoamerican religion, and the practices of worship in caves continues today.20 We propose therefore that the four gods in AGN 504 and 507v follow the cave, an indication that tribute, offerings, as well as the ceremonies have to be consecrated to the earth and the days. Previously Jansen and Pérez Jiménez proposed to read the crocodilian creature of AGN 506r as the first day of the calendar. We believe that the association of this Mesoamerican depiction with the four gods of the veintena tribute allows us to read the giant open jaws of the crocodile as both an indication of locality (cave) and timing (day) of the tribute-paying activity.21

4. From right to left: A Spanish encomendero and an indigenous ruler seated and facing one another; a crocodilian creature; Tlaloc and a goddess facing one another; a medallion representing Xipe; a medallion representing a solar god. Proposed reconstruction. Archivo General de la Nación, Mexico City, ramo Vínculos, vol. 272, segunda parte, exp. 11 y 12, leg. 10, ff. 504-507.

While the depiction of the four gods related to the veintena tribute periods seems valid, a small fragment slightly complicates the picture (fig. 5). In what is left of a corner of a page, the top part of a conical hat with cotton ball feathers attached to it is recognizable. The top ending of a stick is also visible on the left. Jansen and Pérez Jiménez identified it as part of the female deity on the left of AGN 504v.22 However, on a close inspection, the size, placement on the page, and orientation in relation to the structure of the paper makes this impossible. The headdress must have been located on the top left of a page and none of the extant pages fit this description. Conical hats with cotton balls are typical of the god Xipe (see, for example, Florentine Codex, vol. 1, f. 12r) or Toci and Tlazolteotl (see, for example, Codex Borbonicus, p. 13) in the Central Mexican pantheon. The conical hat is also an attribute of Quetzalcoatl, although the stick he carries is usually curved. Finally, Codex Vienna, p. 26, depicts a procession of eight characters in what has been interpreted as a harvesting ceremony.23

5. Conical hat. Lafragua 10r, fragment. Codex Yanhuitlan (C.B. 86922-41210404), Biblioteca Histórica José María Lafragua de la Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Mexico.

Following the procession, more ritual objects are listed, among which also conical hats and large sticks. This scene from a Mixtec codex is important not only because it constitutes a close cultural and visual antecedent to the fragmented image of Codex Yanhuitlan, but also because it indicates that the Yanhuitlan fragment may have represented not only an object (the hat), or a god, but a ritual activity. A close inspection of the original is needed to establish whether it is indeed executed on the same paper as the AGN section, but the fragment indicates that there was a more extensive depiction of pre-Hispanic gods, beyond those four extant today. If the interpretation of those now known as the periods of tribute collection is right, then another set of depictions of clear Mesoamerican religious contents was present that is now lost. Codex Yanhuitlan was possibly never concluded, as a few unfinished drawings suggest (Lafragua 7v, 9r and AGN 505r), and may never even have corresponded to one overarching set of contents and structure. Our following analysis stresses this aspect in the interpretation.

Inks, Torn Paper, and Multiple Hands

The first part of the codex appears to have undergone the largest intervention after its initial execution.24 Additions can often be visually identified by the presence of an ink of different color than that used to make the drawings of the codex. The color of the later additions is black, where the original ink has now faded to brown. This is a common property of iron-gall inks found in many older manuscripts. The fact that the ink used to make the corrections has remained completely black would suggest however that this is something other than iron-gall ink. Doesburg and colleagues state that the black ink is carbon based, a common precolonial writing material.25 Chemical characterization, which is now possible with a wide range of non-invasive techniques may offer crucial insights on different interventions by distinguishing chemically different but visually similar inks.26 These different inks correspond to what are clearly different hands with different levels of skill. A rather unskilled and unsteady hand made what seem to be purely decorative additions to the existing drawings. These are clearly visible on Lafragua 11r (fig. 6), where flower motifs and other roof decorations, as well as an extension of the staircase, were added to the temple depicted on the left side. Similar decorations were also added to the palace on Lafragua 5r and they seem to be by the same hand as the decoration of shields and one added figure on Lafragua 5v. If so, these decorations all date from a rather late period, as is suggested by the classical seventeenth century Louis XIV style large curled hairdo of the man on the bottom right of Lafragua 5v.

6. A tribute scene, heavily intervened. Lafragua 11r. Codex Yanhuitlan (C.B. 86922-41010404), Biblioteca Histórica José María Lafragua de la Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Mexico.

A second intervention took place on Lafragua 11r, which had a different purpose. Rather than being purely decorative, the objective of this repaint was to obscure information. In figure 7 the current state and a partial reconstruction of the original are given. As can be seen, the original calendar glyph of the seated figure was Deer. While Jansen and Pérez Jiménez suggest that this may have been 4 Deer, there is no reason to assume that the numeral was altered.27 Perhaps here too the chemical characterization of the inks could provide the answer. As mentioned by Doesburg and colleagues, the black section in the entrance to the temple/palace below was also created during the later intervention by the editor, possibly to cover up something underneath.28 This means that the interpretation of this place as Tilantongo or “Black Town” is somewhat problematic.29

7. Left: Current state. Lafragua 11r, detail. Right: Underlying drawing. Reconstruction by Ludo Snijders. Codex Yanhuitlan (C.B. 86922-41010404), Biblioteca Histórica José María Lafragua de la Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Mexico.

This black ink is found in at least two different occasions. The first one corresponds to the black calendar glyphs found on the top left of Lafragua 11r (fig. 6), which is indeed a fragment. The ink and drawing style is similar to the corresponding scenes found on the reverse of the page (fig. 8) and on Lafragua 12v and the fragments now pasted together as page Lafragua 13. This stylistic difference, coupled with the different ink employed finds a counterpart in the paper, which, as we remarked, has a different watermark on folio Lafragua 12. This suggests that page Lafragua 11r was altered with the purpose of changing the pre-existing narrative, followed by the addition of new pages that strengthened and further developed the new contents. If these pages are read in the reverse order, as was proposed earlier, the series of lords of neighboring villages, depicted in Lafragua 11v and 12 (see fig. 8), cannot be facing the image of the cacique and the encomendero found on AGN 506v, as suggested by Sepúlveda and Herrera and Jansen and Pérez Jiménez,30 nor do they face the depiction of the glyph of Yanhuitlan and the people in its service on Lafragua 1v, according to Doesburg and colleagues.31 In the right-to-left reading order, all the lords in Lafragua 11v face towards and follow the scene on Lafragua 11r, i.e. Lord 8 Deer. This calls to mind a precolonial writing convention seen, for example, in Codex Nuttall, where dozens of lords of subservient towns are portrayed paying respect to Lord 8 Deer.32 The two styles employed are markedly different, as will be discussed in the next section.

Style, Models, and the Conventual Schools

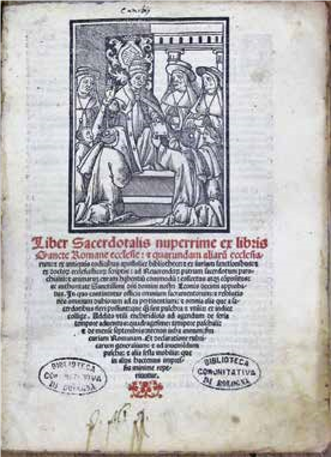

A stylistic analysis of Codex Yanhuitlan reveals the close connection of the main author (or tlacuilo) of the manuscript with the art schools founded by the Franciscans in Mexico-Tenochtitlan the newly established capital of New Spain. An illustration (fig. 9) from the Liber Sacerdotalis printed in Venice in two editions in 1523 and 1534 shows clearly that European printed books were a stylistic and iconographic referent for one of the artists of Codex Yanhuitlan, particularly in the fashioning of the tonsured heads, which bear a close resemblance to the heads in Lafragua 5r (fig. 10). Bishop Juan de Zumárraga owned a copy of the Liber Sacerdotalis and a few surviving illustrations from the earliest book printed and illustrated in the New World, the Manual de adultos (National Library, Madrid), printed by Juan Pablos in Mexico City in 1540, which bear a close resemblance to the Italian antecedent.33 Another illustration taken from an early book printed in the workshop of Juan Pablos clarifies the identification of the central figure of Lafragua 8v (fig. 11), which has been a matter of disagreement among scholars. The man, who wears a long robe and large hat, with a knotted rope on the cap, has been interpreted as a religious figure, such as a vicar or bishop.34 More recently, Jansen and Pérez Jiménez and Doesburg and colleagues believed it to be a lay character.35 Figure 12, an illustration that first appeared in the 1553 Doctrina by Pedro de Gante, depicts one of the seven spiritual works of mercy: instructing the ignorant. A man on the left is engaged in a lively conversation with a group of smaller men on the right. The works of mercy involve lay people, and not friars or priests, in the caring for the material and spiritual wellbeing of those in need. The people offering the works are often depicted wearing a long robe that covers the whole body and a large hat, a reference to the first act of mercy attributed to a traveling Samaritan. The scene of the Mexican engraving therefore shows a double relationship with the page from Codex Yanhuitlan, in both form and content. Not only can the central character be identified with a lay person, but it can also be argued that he is in fact engaged in a spiritual work of mercy, because the topic of the animated conversation seems to be the presentation and teaching of the rosary.36 García Valencia and Hermann Lejarazu have noted the complexity of the gestures in Codex Yanhuitlan, which, nonetheless, do not bear much resemblance to the equally complex gesturality of the Mixtec codices.37 Many of the early illustrations produced for Juan Pablos, such as the one depicting the spiritual works of mercy, show the typical rhetorical gestures of Renaissance treatises, an indication that such representational conventions were circulating in New Spain’s artistic, intellectual, and indigenous circles from a very early date.

9. Illustration from Liber Sacerdotalis by Alberto da Castello (Venice: Melchiore Sessa and Pietro Rabani, 1523), illustrating a crowd of priests kneeling to the Pope and other prelates. Biblioteca dell’Archiginnasio, Bologna.

10. Heads of cabildo members. Lafragua 5r, detail. Codex Yanhuitlan (C.B. 86922-8692241010404), Biblioteca Histórica José María Lafragua de la Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Mexico.

11. A Spaniard holds a large rosary in his hands, while engaging smaller indigenous figures. Lafragua 8v. Codex Yanhuitlan (C.B. 86922-41010404), Biblioteca Histórica José María Lafragua de la Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Mexico.

12. The Works of Mercy: Instructing the Ignorant. Page from Doctrina cristiana en lengua mexicana, by Pedro de Gante (Mexico City: Juan Pablos, 1553). Illustration size 3 × 2 cm. Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas, Austin.

Another interesting case of correlation between circulating prints and Codex Yanhuitlan imagery is found in the two large medallions depicting a solar god, recognizable by his nose and collar jewelry, and Xipe Totec (AGN 504r and 507v) (fig. 4, left), previously discussed. Although they depict presumably pre-Hispanic objects, as the solar rays that encircle the heads indicate, the profile rendition of the face of the two gods is not consistent with known Mixtec gold work, whose depictions are frontal and often three-dimensional. Rather, the so-called medallic portrait of Christ, which became increasingly common in the fourteenth century, seems to constitute a closer iconographic and stylistic referent.38 Unlike any pre-Hispanic antecedent, in the images of AGN 504r and 507v only the head of the god is depicted, emphasizing the naturalism typical of a portrait rather than a full godly depiction. A print by Hans Burgkmair was widely copied and also appears in Novohispanic books in different versions produced locally (fig. 13).39

13. Portrait of Christ. Illustration from Vocabulario en lengua zapoteca, by Juan de Córdoba (Mexico City: Pedro de Ocharte, 1573). Illustration size 7 × 7 cm. John Carter Brown Library.

All these references point to an artist whose background was well rooted within the intellectual and literary culture of the friars. The presence of Nahua conventions may constitute a further proof that the artist of Codex Yanhuitlan had received an education in the schools of the Nahua capital, such as San José de los Naturales, in Mexico-Tenochtitlan, or Santiago Tlatelolco.40 In this respect, Codex Sierra, a mid-sixteenth-century manuscript from the Mixtec-Chocho community of Santa Catarina Tejupan in the Mixteca Alta, refers to central Mexican Nahua artists brought to town by the friars to instruct and interact with the local community and execute works in the church.41

Lafragua 5r was also altered, albeit in a different manner. While previously both Sepúlveda y Herrera and Doesburg and colleagues recognized several interventions in them, we are not entirely in agreement with their assessment.42 They suggest that the three central figures of Lafragua 5r (fig. 14 on the right), whose outline is now a coffee color, were added later than the rest of the figures whose outline is black. We rather consider the coffee colored figures to be part of the initial stage, the darker and crisper outline of head and hair of the crowd being a later addition. The figures in profile in the crowd, in fact, had an elongated skull shape and hairdo similar to the central figures, still somewhat visible underneath the darker black hair (fig. 14, middle). The figures drawn from the back are made with the same dark ink, and are in a distinctly European style that tries to introduce some perspective into this scene by portraying them from behind (fig. 9). This seems a reverse case to the one previously discussed. The artist who employed a more indigenous style drafted the earlier version, on top of which the artist more confident in Western conventions intervened. Perhaps the two tlacuilos were working hand in hand and adding to one another’s intervention. It is in fact noticeable that the central and intermediary figures, which we interpret as priestly males, following a suggestion by Jansen and Pérez Jiménez, were not altered, remaining more clearly in a precolonial manner, while the superimposed stylistic interventions were done on the crowd that is drawn with a characteristic Western flare.43 Finally, there seems to have been a clear intent to remove the birds carried by the priestly figures. These may have been objects of power given to the political rulership, thus signaling a dangerous mixing of sacred and civil authority common among indigenous communities, but despised by the Spaniards. Different styles, which point to different moments or even localities of production, may have corresponded to different ideological concerns in a rapidly changing political climate in Yanhuitlan, as will be argued below.

Discussion and Conclusion

There is no direct historical evidence regarding the exact timing and circumstances of production of Codex Yanhuitlan. The latest recorded date in the document is 1544 (Lafragua 3r), which should then be taken as a terminus post quem. This was however a critical date in Yanhuitlan’s early colonial history, as the yya don Domingo de Guzmán and two more gobernadores were in that year under trial by the Inquisition in Mexico City.44 As all authors who have previously studied the codex recognized, the date of 1544 does not correspond to the construction of the church, the episode depicted on the page, which only began in 1550.

The years between 1546 and 1558, which followed the release and reinstatement of don Domingo in Yanhuitlan may have seen a rapid but profound readjustment in the local political situation both within the indigenous rulership and in the external relationship with the Spanish power, reflected in the drafting of Codex Yanhuitlan. Jansen and Pérez Jiménez have suggested that yya Gabriel de Guzmán may have sponsored the composition of the manuscript to celebrate his succession in 1558, after the death of his uncle, don Domingo.45 Doesburg and colleagues, on the other hand, believe that the time gap between the last recorded date (1544) and 1558 is too large.46 Any year prior to 1558 would imply that the patron was yya Domingo de Guzmán. The hypothesis of Jansen and Pérez Jiménez we believe does not take sufficiently into account the clear tributary aspect of the manuscript, including a seemingly condemnatory stance against Spanish exploitation (see Lafragua 2r), which, in our view, makes it difficult to read the document as a historical statement on the legitimacy of the colonial yuhui tayu. The extant pages, furthermore, do not contain any information regarding Yanhuitlan’s genealogy, an aspect that would have been of primordial importance in case the document had been produced at a time of succession.

Very little is known of don Domingo’s rulership in the town after the Inquisition trials. Works in the convento started in 1550 and by 1558 the Dominicans were able to host their regional chapter in the new building.47 While don Domingo’s opposition and resentment against the friars is well known through the Inquisition documents, his ambivalent and ultimately defeated rulership after he and the gobernadores were released from jail, is more difficult to assess. In 1548, just two years after the case with the Inquisition was settled, don Domingo de Guzmán was mentioned as gobernador, the title once held by another important local leader, don Francisco de las Casas, who had been tried with him, but had at that point presumably died.48 This mention is found in a tasación (tribute list) that the people of Yanhuitlan were obliged to give to don Domingo as governor for the time of his tenure.

As Doesburg and colleagues have noticed, in the same year another litigation regarding tribute on the part of the community was also settled, this time involving the encomenderos Francisco and Gonzalo de las Casas.49 Albeit indirectly, these two related documents may hint at a political readjustment after the death of the gobernador don Francisco, which saw a new allegiance of the cacique with the Spanish power. The death of gobernador don Francisco, who was a religious authority, as evinced from the Inquisition trials and who was a staunch adversary of the friars at least as much as don Domingo, may have caused deep political and strategic readjustments, which had to be resolved by yya Gabriel after he succeed to the throne. The yuhui tayu of Yanhuitlan had several challenges from subject towns, most notably Tecomatlan, and local yya had no shortage of reasons to alter the document in order to better further their case in court.50 If it is in fact true that the document was altered before its final dismemberment in the early eighteenth century, this would also imply that several folios had to be added and the manuscript as a whole had to be unbound and rebound. The long history and use of the manuscript prevents the understanding of the original purpose and actually raises the question whether there was ever one single and “final” reason for its creation.

Although the genre of the codex remains unclear, its pictographic contents show several similarities with contemporaneous documents produced by indigenous communities to prove abuse perpetrated by Spanish authorities. Codex Tepetlaoztoc, or Codex Kingsborough (1553), from a town in the north of the State of Mexico, for example, details the complaints against the exploitative and violent behavior of the encomendero and other Spanish officials.51 The longest part of the document deals with the excessive tribute that was requested annually. In a manner similar to Codex Yanhuitlan, large quantities of raw material (grains or gold) are represented in a rather simplified and concise manner, while precious items are depicted in a large format with a specific attention given to details. Folio 216r (fig. 15) depicts a golden necklace, whose beads show the same pre-Hispanic motifs, such as volutes, found in the rosary necklace in Codex Yanhuitlan (Lafragua 8r-8v, fig. 11); only this time the central piece is represented by a flower with nine bells. In the same page, there are also several golden disks, a depiction found on AGN 505r in the case of Codex Yanhuitlan. Obsidian mirrors are found on Codex Tepetlaoztoc, folios 224v and 225r and Codex Yanhuitlan, AGN 507r. Large feather works in the form of fans are seen on folios 226v and 227 of Codex Tepetlaoztoc and CCSD 3v and AGN 505v of Codex Yanhuitlan.

15. Depiction of tribute and Spanish violence and exploitation. Codex Tepetlaoztoc, fol. 216r. The British Museum, London, 21.5 × 29.5 cm.

The reason why luxury items, reportedly given to the encomendero so he could finance his travel back to Spain, are represented in such details in this Central Mexican codex is because their value rests more in the quality and craftsmanship required for their execution than in the mere quantity. For the same reason, several houses and residences are depicted in large scale, thus documenting with details the amount of work, resources, and efforts necessary for their construction (folios 221r, 228v, and 234r). Along this interpretative line, the two churches depicted in Codex Yanhuitlan (Lafragua 3r and 17v) may be considered the result of tribute collected in different periods, in order to document historically the burden placed for their execution on the local population. Was perhaps tribute exerted first by the yya (Lafragua 9v; fig. 3, left) and then by the Dominicans (Lafragua 17v)? In the first instance, the seat of power of a cacique is still visible attached to the church (the ruler has been erased), and the church and cacique are in turn surrounded by glyphs demonstrating the extension of the cacicazgo of Yanhuitlan. In the second case, the church stands alone with no other element but the glyph of Yanhuitlan under the church. Differently from the earlier depiction, a cross and flag are prominently displayed on top of the construction, perhaps a sign of the ultimate triumph of the Dominican project over local Mixtec interests.52

Documents such as that from Tepetlaoztoc often include scenes of physical abuse in which. Spanish officials subjugate indigenous people with swords, sticks, and fire. Despite the weakness of the visual data from Codex Yanhuitlan, archival information confirms that the yya of Yanhuitlan was assassinated by a Spaniard in 1529, during a period of chaos following the destitution of the first encomendero, the conquistador Francisco de las Casas.53 The seat of power, the yuhu tayu of Yanhuitlan is said to be of yya 9 House, also referred to as Calci (house, in Nahuatl) in the historical documents, since the first recorded date in the document (Lafragua 5r). Even in that instance, however, the name 9 House is connected to the throne, not to the character seated on it (fig. 16), which means that the seat of power and the person in charge were not one and the same. According to a more or less accepted -chronological order of the pages, the last time 9 House is connected to the town is on Lafragua 1v (fig. 17), likely associated with the dates of 1528-29.54 Does that mean that lord 9 House was finally and officially dethroned, or was he actually murdered? Could he be the cacique/governor who was said to have been assassinated? According to accounts given by Don Gonzalo, son of lord 9 House (Calci), his father had indeed died in the late 1520s, although no mention is made that he was murdered.55 The same person also challenged the legitimacy of don Gabriel, claiming a political authority that was perhaps once shared by more than one figure.56 What we suggest is that different political figures, most commonly referred to as caciques and gobernadores using Spanish terminology in colonial documents, shared and fought for their authority in the turbulent years of the establishment of Spanish rule. Lafragua 1v (fig. 17) still shows the foot of an otherwise completely erased Spaniard on top of the glyph of Yanhuitlan. The foot appears to wear the same stocking as other Spaniards in the codex (see Lafragua 2r). The slight inclination of the foot suggests that he is engaged in a physical activity.57 The scene on folio 1v was intentionally erased, but the portion that needed to be removed is large enough to indicate that it was indeed a scene and not only a person: a small, undistinguishable detail is visible in the top left corner of the glyph. Could this be the scene of the murder of lord 9 House? This admittedly hypothetical and fragmented interpretation would, however, fit the rapidly changing political situation that followed the reinstatement of cacique don Domingo and gobernador Francisco de las Casas in Yanhuitlan, in the later 1540s and 1550s. At the same time, the chronological period covered by the manuscript was equally one of extreme political turbulence and upheaval.

16. Yya seated on a throne connected to the name 9 House. Lafragua 5r, detail. Codex Yanhuitlan (C. B. 86922-41010404), Biblioteca Histórica José María Lafragua de la Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Mexico.

17. Toponym of Yanhuitlan with the name of Lord 9 House. Lafragua 1v, detail. Codex Yanhuitlan (C. B. 86922-41010404), Biblioteca Histórica José María Lafragua de la Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Mexico.

The complex historical situation in Yanhuitlan following the Inquisition trials was likely the scenario against which Codex Yanhuitlan was created, and the recent and tumultuous past of the town newly and rapidly imagined and recounted. In the lapse of just a few years, different competing forces within Yanhuitlan’s traditional authority disputed their legitimacy. As an unfinished and redrafted document, Codex Yanhuitlan shows in its own material and stylistic changes the confrontation among different conceptions of indigenous power. Our analysis aims to demonstrate how a closer look at the formal and material aspects of manuscript production can corroborate or disprove iconographic and historical approaches, enriching the general discussion of culture change in the early years of indigenous and colonial New Spain.

The influence of Mexico-Tenochtitlan’s conventual schools, evidenced in the style of most of its pages, clashes with the reverse reading order of the pages, a unique case for a book-type manuscript. The odd placement of the year dates, depicted according to Mixtec conventions, may also indicate that the manuscript was not painted by a Mixtec tlacuilo, unlike some of the other pages that-as discussed-clearly show the use of Mixtec stylistic conventions. Finally, the AGN pages, with their unusual depiction of Mesoamerican gods and veintena periods, also reflect the different and at times contradictory views regarding tribute payment, the thorniest issue addressed in the document, given also the many political implications it carried. The material and stylistic analysis of Codex Yanhuitlan evidences how deep and seemingly rapid was the penetration of Catholic religious and cultural institutions in an indigenous town, Yanhuitlan, situated far away from the metropolitan center of New Spain. It seems possible that the years spent by cacique don Domingo de Guzmán and gobernador Francisco de las Casas in Mexico-Tenochtitlan and their subsequent return to the Mixteca, as leaders of Yanhuitlan, may have in fact impacted the production of the manuscript, its contents, agenda, and outlook. However, by 1558, the Guzmán leadership finally imposed itself with the accession of don Gabriel. The document as a whole likely remained in the hands of the yya until reused in several court cases in the eighteenth century, when Codex Yanhuitlan was dispersed into many fragments along with the definitive dissolution of the cacicazgo.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)