Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Salud Pública de México

versión impresa ISSN 0036-3634

Salud pública Méx vol.52 supl.2 Cuernavaca ene. 2010

IMPLEMENTATION OF THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION IN LATIN AMERICA

Capacity building and human resource development for tobacco control in Latin America

Capacitación y desarrollo de recursos humanos para el control del tabaco en América Latina

Frances A Stillman, Ed D.

The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Baltimore, MD, USA.

ABSTRACT

Objective. To assess capacity and human resources in Latin America countries and compare with other countries. Material and Methods. Data were gathered through needs assessments that were conducted at the 2009 World Conference on Tobacco or Health, and the 2nd Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco-International American Heart Foundation, Latin America Tobacco Control Conference held in Mexico City in 2009. Results. In comparing Latin America respondents to respondents from other countries, we found that the average number of years in tobacco control was higher and the majority of respondents reported higher levels of educational attainment. Respondents reported lack of funding and other resources as their number one challenge, as well as, tobacco industry interference and lack of political will to implement tobacco control policies. Conclusions. In Latin America there are some countries that have made significant progress in building their capacity and human resources to address their tobacco epidemics, but much still needs to be done.

Key words: tobacco control; capacity building; assessment; Global Tobacco Research Network; Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

RESUMEN

Objetivo. Realizar un diagnóstico sobre la capacitación y los recursos humanos en América Latina y comparar con otros países. Material y métodos. Los datos se obtuvieron a través de una encuesta realizada durante la Conferencia Mundial Tabaco o Salud de 2009 y la segunda Conferencia de Control del Tabaco para América Latina de la Sociedad de Investigación sobre Nicotina y Tabaco (Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco) y de la Fundación Interamericana del Corazón llevada a cabo en la ciudad de México en 2009. Resultados. Al comparar las respuestas de América Latina con las de otros países, observamos que el promedio de años trabajando en control del tabaco era mayor y que la mayoría reportó un mayor nivel de estudios. Los encuestados identificaron la falta de recursos y de financiamiento como su mayor desafío así como la interferencia de la industria y la falta de voluntad política para implementar políticas de control del tabaco. Conclusiones. Algunos países de América Latina han hecho enormes avances en cuanto a la capacitación de sus recursos humanos para afrontar la epidemia del tabaco, sin embargo, todavía queda mucho por hacer.

Palabras clave: control del tabaco; capacitación; evaluación; Red Global de Control del Tabaco; Convenio Marco para el Control del Tabaco

Low- and middle-income countries face an increasing threat to public health from an escalating epidemic of tobacco use.1 The strong scientific evidence of tobacco-attributable disease and its enormous adverse impact on global public health provides sufficient rationale for giving high priority and adequate resources to tobacco control programs. The WHO Framework Convention for Tobacco Control (FCTC) was built on a large and ever growing evidence-base concerning tobacco control and health, economics, behavior, policy and even poverty. However, many countries scarcely have the capacity to develop and implement best practices that the FCTC recommends. Global tobacco control capacity has grown in response to the FCTC as noted by recent national tobacco control developments in many countries. To meet FCTC obligations, however, much still needs to be done to have adequate resources, trained personnel, adequate leadership and other components that are necessary for national capacity for tobacco control, which is beyond mere funding for tobacco control.

Countries are at different levels of readiness to implement their WHO FCTC obligations, as well as to implement their own national tobacco control programs. There is a great deal of diversity among the countries as to the efforts that they are undertaking to control this epidemic as well as differences in their participation in the FCTC process.2,3 This paper will look at capacity and human resource development for tobacco control in Latin American countries and compare this to what is happening globally. For example, in Latin America, Argentina has not yet signed or ratified the FCTC, while Brazil won a hard pressed fight and achieved ratification of the Convention.4 Brazil has an impressive policy record and has conducted large-scale national studies as well as specific epidemiologic studies on tobacco related topics. One of their major achievements was the implementation of pictorial health warnings over a 100% of one side of the cigarette package.1 Mexico has also had some successes, but also faces many challenges to implement tobacco control. Mexico was the first country in the Western Hemisphere to ratify the FCTC, but shortly after ratification the government entered into an agreement with the leading tobacco companies operating in the country to restrict tobacco advertising, marketing, and labeling, in exchange for a large monetary contribution to the Fund for Protection against Catastrophic Costs of the System for Social Protection in Health.1,5 This agreement was not renewed in 2006 and Mexico has been able to implement comprehensive smoke-free public place restrictions in Mexico City, and recently implemented smoke-free legislation for the entire country. However, overall in the region, significant barriers still exist to implement known best practices for tobacco control. In the long run, the FCTC will only be successful in countries that have strong and durable capacity and human resources for tobacco control.

Materials and Methods

Defining national tobacco control capacity

Our work with the Global Tobacco Research Network (GTRN) focuses on building an information network and assessing national capacity, which we define as the "indigenous capability of countries to deliver comprehensive, multi-sectoral action so as to provide the appropriate prevention and control strategies to reduce tobacco use in their countries".6 Building tobacco control capacity is necessary and is addressed in the FCTC by referring to the "transfer of technical, scientific and legal expertise and technology to establish and strengthen national tobacco control strategies, plans and programs". In addition, the FCTC's Article 22.1 recognizes the need "to strengthen country capacity to fulfill their obligations arising from the Convention, taking into account the needs of developing countries, especially those with economies in transition". Furthermore, Article 26.1, recognizes the importance that financial resources play in achieving the objective of the FCTC.7

Figure 1 presents our simple conceptual model of national capacity, which emphasizes three essential components: empirical evidence, infrastructure and networking/leadership.6

These components of capacity ensure that individual countries have the data, knowledge, tools, people, and organizations needed to develop sustainable tobacco control programs and implement the FCTC. National capacity building, therefore, refers to efforts aimed at enhancing at least one of these three elements.6 In practice, national capacity building is often reflected through the development of a national plan of action, designation of a lead government agency for tobacco control, building of a cohort of tobacco control professionals, and research initiatives aimed at gathering necessary local data to promote and evaluate policy initiatives. To be effective tobacco control programs need to be sustained, comprehensive, and integrated.8 Although funding is necessary, it is not sufficient to accomplish effective tobacco control. Providing adequate funding is just the first step in gaining capacity to manage, develop and implement effective comprehensive programs. Capacity requires staff training and skill development, especially learning how to use funding effectively.9 In fact, one of the major accomplishments of tobacco control in the United States in 1990s was the creation of a tobacco control infrastructure and a trained, professional workforce with full time employees focused on tobacco control issues.9,10

Capacity assessment for tobacco control in Latin American countries

To assess capacity in Latin America countries, we will present data that has been gathered through needs assessments that have been conducted at two recent international conferences on behalf of the Global Tobacco Research Network (GTRN).11 To further highlight information on specific countries we also use data from the WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008: MPOWER Package.3 While data that provides details on country capacity and human resources is still fairly limited, by combining the available information, we can begin to highlight some specific capacity needs that are present in Latin America. In addition, these data can be used to compare Latin America countries to other countries around the world to better understand any specific needs in Latin America.

Assessment sample and methods

We administered a needs assessment survey to all participants who pre-registered to attend the 2009 World Conference on Tobacco or Health (WCTOH) in Mumbai, India. The survey was conducted online between January and February 2009. A link to the survey instrument was emailed to all individuals who preregistered for the WCTOH (n = 1300). Respondents were asked information related to their experience in tobacco control, their priorities and needs, the challenges they face in their tobacco control work, and the extent to which they network and collaborate with each other. The survey also included questions tailored to specific groups, including: researchers, advocates, clinicians, educators, and policymakers, as well as open-ended questions for all groups. Approximately 45% (n=585) of the solicited participants filled out the survey, of whom 3.9% were from Latin America. Latin American participants were eliminated from the data reported here, in order to allow for a more meaningful comparison with a subsequent survey of Latin American tobacco control capacity.

We administered the same survey in Spanish, before the 2nd Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco-International American Heart Foundation Latin America Tobacco Control Conference, which took place in October 2009. The 70 respondents were conference attendees who were also members of the Latin America Coordinating Committee (CLACCTA), a longstanding network of tobacco control advocates and professionals in Latin America (See Champagne et al, this issue). The majority of respondents (69%) came from three countries: Argentina (31%), Mexico (16%), and Uruguay (12%). The other 31% of participants were from Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Peru, and the Dominican Republic. The full report of these data is available on the GTRN website (http://www.tobaccoresearch.net).

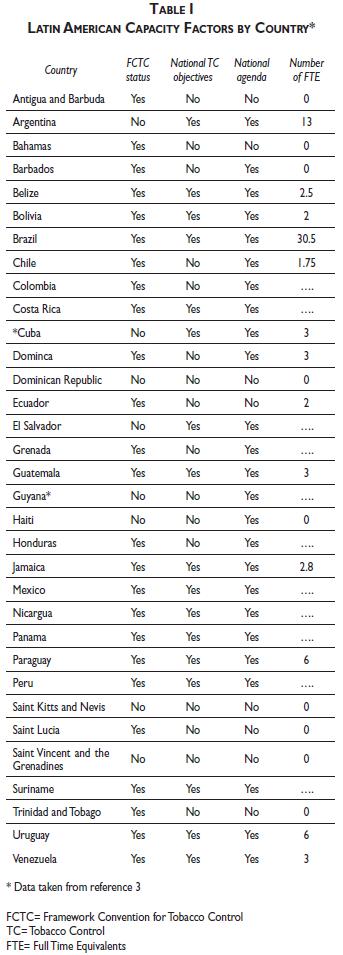

Finally, data on capacity from the WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic (2008) are presented here to provide additional information concerning Latin America. Although limited in scope, these data provide information that allows for comparison across many countries in Latin America, on issues including FCTC ratification status, existence of national tobacco control objectives, national tobacco control agenda, and the number of employees devoting 100% of their time to tobacco control (full-time equivalents -FTEs)

Results

In comparing Latin America respondents to respondents from other countries, we found that the average number of years in tobacco control was higher for respondents from Latin America. On average, respondents from Latin America reported 6-10 years of working in tobacco control as compared to only 1-5 years from respondents in other countries. The majority of respondents from Latin America were highly educated, with 65% holding a Master's degree, PhD, or MD. These findings indicate that there is already a cadre of highly educated and experienced tobacco control professionals working in the Latin America region.

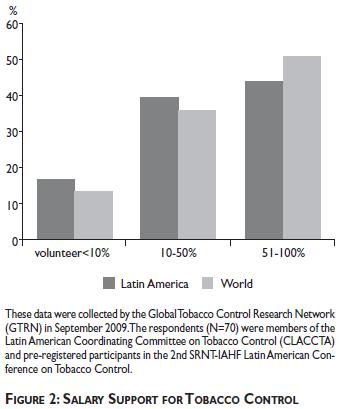

Figure 2 highlights the salary support for tobacco control. The survey found that respondents from Latin America were a bit more likely to be volunteers and receive no salary support as compared to respondents from other parts of the world. There was also a difference between respondents from Latin American and respondents from other parts of the world on receiving at least 50% of their funding for tobacco control efforts. The respondents in Latin America were also somewhat less likely to not have staff focusing on tobacco related issues. While the actual difference between these groups is not very large, respondents from Latin America had fewer persons whose jobs were more focused on tobacco control when compared to other countries. This is a major indicator of tobacco control capacity and as the number of persons who are employed full time in tobacco control increases, the likelihood that these individuals will be able to develop and implement programs and policies should increase.9 In Latin America, another 39% of respondents receive partial salary support for their tobacco control work, and 17% work entirely on voluntary basis. Latin America had more persons working as unpaid volunteers in tobacco control. While this demonstrates a great interest in trying to improve tobacco control, it reinforces the need for more funding and the development of tobacco control as a full-time profession.

When asked to rate their access to tobacco control resources, respondents from Latin America indicated that they had excellent access to high speed Internet, better than reported by respondents from other regions. Latin America respondents also indicated that their preferred method to receive training is through regional trainings. The top three topics they would like to receive training on were reported as interest in learning more on how to: 1) implement mass media campaigns, 2) conduct surveillance and evaluation, and 3) develop research protocols. When asked who they seek assistance from, most Latin America respondents indicated that they seek assistance from colleagues in or outside of their organization. However, there seemed to be less access to a professional mentor or advisor. This could be explained by the fact that mentorship is generally not as easily obtained as other types of assistance and indicates the need to foster such relationships among researchers in Latin America. The respondents from Latin America as well as from other countries still reported lack of funding and other resources as their number one challenge. In addition, tobacco industry interference in their countries as well as lack of political will to implement tobacco control policies was also indicated as other major obstacles that were present.

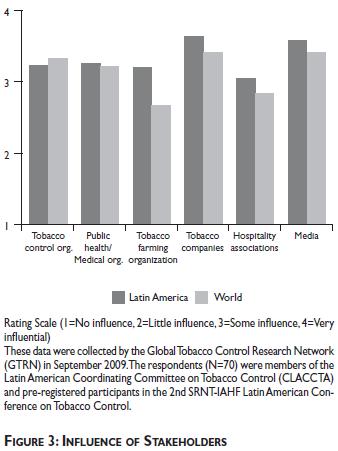

As indicated in Figure 3, respondents from Latin America reported more interference from the tobacco industry as a primary barrier to being able to conduct their work. The influence exerted by tobacco companies appears to be slightly greater than in other parts of the world. Many respondents were from Mexico and Brazil, where the tobacco industry is very large and powerful. It may not be coincidental that one of the richest men in the world lives in Mexico and heads a tobacco company. Respondents also noted that Latin America, especially Brazil and Mexico, have substantial amounts of tobacco agriculture and face obstacles from stakeholders associated with tobacco farming in their countries. Latin America respondents also reported a greater influence of the media than respondents from the rest of the world. From our data, we are unable to determine if the media coverage of tobacco control is supportive and positive, or non-supportive and negative. We do not have enough information to understand the differences of these influences by country. However, there has been some research on media coverage in Mexico which indicates that media coverage on tobacco control tends to be more positive or of a neutral/mixed type of coverage of tobacco than negative coverage.12 However, more research on this topic would be helpful to understand differences in media coverage that exits between countries.

Table I provides additional information on capacity for tobacco control in Latin America, based on data from the 2008 WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic.3 It is noteworthy, that while Argentina has not ratified the FCTC they reported 13 full-time equivalents (FTEs) in tobacco control, which was the 2nd highest number reported after Brazil. It is of interest that while Mexico reported that they had signed and ratified the FCTC, had national objectives and had a national agenda, they did not report any FTEs working in tobacco control. Many other countries also reported no FTEs working in tobacco control or were unable or did not provide this information. These data are important and need to be collected to accurately assess national capacity. A more systematic method to obtain these data is needed as well as a more comprehensive assessment tool that can capture more of the indicators of capacity and human resources. Beyond knowing if the countries indicate that they have achieved certain capacity indicators, it will be important to better understand the quality of the actions and the actual implementation of their plans and objectives.

Conclusions

The information from this study indicates that a few Latin American countries have been able to implement national policies that are evidence-based and are making progress in having the knowledge, tools, data, people, and organizations needed to implement comprehensive and sustained tobacco control programs. However, it is evident that significant barriers still exist in many Latin American countries, which inhibit development of the necessary capacity to build and sustain comprehensive tobacco control programs. In addition, this paper highlights that a lack of ongoing tracking or monitoring of country tobacco control capacity still exists.

The capacity assessment that we describe in this paper provides information that can be used for planning and improving capacity and human resources for tobacco control in Latin America. Conducting such capacity assessments is an example of a model approach to information gathering and monitoring that needs to become part of a comprehensive approach to understanding tobacco control in Latin American countries, including whether they are meeting some of the basic provisions for capacity building outlined in the FCTC. Development of sufficient national tobacco control capacity does not automatically follow from the attainment of short-term policy objectives (for example, the adoption smoke-free laws or improved health warnings). The tobacco control community has done an excellent job in determining the best practices in policy and programs needed for comprehensive tobacco control. However, to assure that policy achievements translate into actual reductions in smoking prevalence, tobacco consumption, and eventually save lives, policies must be properly implemented and enforced to promote compliance and normative behavior change. Strong country capacity and human resources are necessary to accomplish these objectives. Making sure policies are translated into meaningful action also requires a comprehensive approach that is delivered in a collaborative and coordinated fashion. This approach needs to be built over time on a strong foundation of skills, tools, data, people, and organizations committed to supporting and sustaining tobacco control policy and practice.

Since the publication of our capacity building model, much change has occurred in tobacco control efforts in many countries.6 We understand that capacity building is a moving target and is changing over time, and our data only encompass 2008 and 2009. This is one of the limitations of our study, as is the limited number of respondents, who may represent a select group of those who work in tobacco control in Latin America. Nevertheless, we believe that these data show an important baseline assessment of capacity in Latin America. Over time, GTRN data is beginning to show progress around capacity building. Funding, while still limited, has expanded and new regional networks are being formed to improve communication and information sharing.13

Strong capacity comes from investments by governments as well as external donors. Governments in some Latin American countries are providing financial support to develop their national level tobacco control programs as well as developing sub-national tobacco programs in states and provinces. In addition, external support agencies, technical partners and other donors have begun to invest substantial time, monetary support, and other resources to build research, surveillance, advocacy and leadership capacity in selected Latin American countries. Latin America also has developed a regional network and has become active in coordinating trainings, and other capacity building workshops to increase the skills and knowledge necessary for the region. Much still needs to be done, but in Latin America there are some countries that have made significant progress in building their capacity and human resources to address their tobacco epidemics. Future capacity assessments should try and obtain more detailed information on these numerous types of activities by country to gain a much fuller understanding of the capacity that is being built and the factors that may be facilitating or impeding this development.

Declaration of conflicts of interest

I declare that I have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health in the United States grant number R01 HL73699. Support for the Global Tobacco Control Needs Assessments was provided by the Global Tobacco Research Network (GTRN) through an unrestricted grant from GlaxoSmithKline to the Institute for Global Tobacco Control at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. The author would like to thank Nasi Dineva and Payal Verma for their contributions to the project.

References

1. Stillman F, Yang G, Figueiredo V, Hernandez-Avila M, Samet J. Building capacity for tobacco control research and policy. Tobacco Control 2006;15 (Suppl I):i18-i23. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014753. [ Links ]

2. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. accessed: 2010 January 20. Available at: http://www.who.int/fctc/text_download/en/index.html [ Links ]

3. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008. The MPOWER Package. accessed: 2010 January 20. Available at: http://www.who.int. [ Links ]

4. Bialous S. Brazil: growers' lobby stalls FCTC. Tob Control; v.13(4); Dec 2004. [ Links ]

5. Samet J, Wipfli H, Perez-Padilla R, Yach D. Mexico and the tobacco industry: doing the wrong thing for the right reason? BMJ. 2006 Feb 11;332(7537):353-4. [ Links ]

6. Wipfli H, Stillman FA, Tamplin S, Silva VL, Yach D, Samet J. Achieving the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control's Potential By Investing in National Capacity. Tob Control 2004;13:433-7. [ Links ]

7. Framework Convention Alliance. Technical and Financial Assistance: The FCTC Commitments. accessed: 2010 January 20. Available at: http://www.fctc.org/index. [ Links ]

8. IOM (Institute of Medicine). Ending the tobacco problem: A blueprint for the nation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2007. [ Links ]

9. Stillman FA, Schmitt CL, Clark PI, Trochim WM, Marcus S. The Strength of Tobacco Control Index. In: Stillman FA, ed. Evaluating ASSIST: A Blueprint for Understanding State-Level Tobacco Control. NCI Tobacco Control Monograph 17. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. NIH Pub. No. 06-6058, October 2006). [ Links ]

10. ASSIST: Shaping the Future of Tobacco Prevention and Control. NCI Tobacco Control Monograph 16. Bethesda, MD: .S. Department of Health & Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. NIH Pub. No 05-5645, May 2005. [ Links ]

11. Stillman FA, Wipfli H, Lando H, Leischow S, Samet J. Building Capacity for International Tobacco Control Research: The Global Tobacco Research Network. Am J Public Health 2005;95:965-8. [ Links ]

12. Llaguno-Aguilar SE, Dorantes-Alonso AC, Thrasher JF, Villalobos V, Besley JC. AnÁ¡lisis de la cobertura del tema de tabaco en medios impresos mexicanos Analysis of the coverage of tobacco in Mexican print media. Salud Publica Mex 30 (Sup 3): S348-S354. 2008 [ Links ]

13. Stillman FA. Results from the Global Tobacco Control Assessment. Paper presented at the 14thWorld Conference on Tobacco or Health, Mumbai, India: March 9, 2009. [ Links ]

Received on: March 26, 2010

Accepted on: July 16, 2010

Address reprint requests to: Frances A. Stillman, Ed.D. The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health,

627 N. Washington Street, 2nd Floor. Baltimore, MD, 21205, USA.

E-mail: fstillma@jhsph.edu