Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Salud Pública de México

versión impresa ISSN 0036-3634

Salud pública Méx vol.52 supl.2 Cuernavaca ene. 2010

SOCIAL MARKETING

Cigarette labeling policies in Latin America and the Caribbean: progress and obstacles

Políticas de etiquetado de cigarrillos en América Latina y el Caribe: progreso y obstáculos

Ernesto M Sebrié, MD, MPHI; Adriana Blanco, MDII; Stanton A Glantz, PhD.III

IDepartment of Health Behavior, Roswell Park Cancer Institute. Buffalo, New York, USA.

IIAdvisor, Tobacco Control, Pan American Health Organization. Washington DC, USA.

IIICenter for Tobacco Control Research and Education, University of California. San Francisco, USA.

ABSTRACT

Objetive. To describe cigarette labeling policies in Latin America and the Caribbean as of August 2010. Material and Methods. Review of tobacco control legislation of all 33 countries of the region; analysis of British American Tobacco (BAT)'s corporate social reports; analysis of information from cigarette packages collected in 27 countries. Results. In 2002, Brazil became the first country in the region to implement pictorial health warning labels on cigarette packages. Since then, six more countries adopted pictorial labels. The message content and the picture style vary across countries. Thirteen countries have banned brand descriptors and nine require a qualitative label with information on constituents and emissions. Tobacco companies are using strategies commonly used around the world to block the effective implementation of WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC)'s Article 11. Conclusions. Since 2002, important progress has been achieved in the region. However, countries that have ratified the FCTC have not yet implemented all the recommendations of Article 11 Guidelines.

Keywords: health communication; health legislation; public policy; tobacco industry; tobacco labeling; tobacco packing

RESUMEN

Objetivo. Describir las políticas de etiquetado de cigarrillos vigentes en América Latina y el Caribe en agosto de 2010. Material y métodos. Revisión de la legislación para el control del tabaco en vigencia en los 33 países de la región; análisis de reportes sociales corporativos del grupo BAT; análisis de información de paquetes de cigarrillos recolectados en 27 países. Resultados. En 2002, Brasil se convirtió en el primer país de la región en implementar etiquetas de advertencias sanitarias pictoriales en los paquetes de cigarrillos. Desde entonces, otros seis países adoptaron advertencias pictoriales. El contenido del mensaje y el estilo de la fotografía varía entre los países. Trece países prohibieron descriptores de marca y nueve requieren una advertencia cualitativa con información de constituyentes y emisiones. Las compañías tabacaleras están utilizando estrategias comúnmente usadas alrededor del mundo para bloquear la implementación efectiva del Artículo 11 del Convenio Marco para el Control del Tabaco (CMCT) de la OMS. Conclusiones. Desde 2002, se ha alcanzado un importante progreso en la región. Sin embargo, los países que han ratificado el CMCT aún no han implementado todas las recomendaciones de las directrices del Artículo 11.

Palabras clave: comunicación en salud; legislación sanitaria; políticas públicas; industria del tabaco; etiquetado de productos derivados del tabaco; envasado de productos derivados del tabaco

Beginning with the United States (US) in 1966,1 governments have required printing health warning labels (HWLs) on cigarette packages to warn smokers about the risks of tobacco use. Since then, at least 116 countries have adopted similar measures with a variety of characteristics.2 As more and more countries ban tobacco advertising, tobacco industry marketing increasingly relies on the cigarette package to communicate with consumers and potential consumers.3

A 1993 study4 evaluated the presence, the content, and the design of HWLs on cigarette packages in 28 countries of Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) and found that 25 of the countries either had a small size, unspecific and weak warning such as "Smoking is harmful to health" printed on the lateral side of the pack similar to the 1966 US warning, or had no warnings at all. A 1999 study5 of cigarette labeling legislation in 45 countries, including 6 from Latin America, assessed the content (developing a scale based on a 10-point content score for 10 specific themes), size and location of HWLs. The study found that packs from developed countries had a higher content score reflecting the presence of multiple and specific warnings, compared to those from developing countries. HWLs in developed countries were also 27% larger and appeared more frequently on both front and back of the packs compared to those from developing countries, where they were on the lateral side of the packs.

Article 11 of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC), in effect since 2005, establishes provisions on tobacco product packaging and labeling, including HWLs, removal of misleading information, and constituent and emissions labeling.6 In November 2008, the third Conference of the Parties (COP3) approved the Guidelines for the implementation of Article 117 (Table I). As of August 30, 2010, all LAC countries but Argentina, Cuba, El Salvador, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Saint Kitts & Nevis, and Saint Vincent & the Grenadines, have ratified the WHO FCTC. Three years after becoming Parties, these countries are legally obligated to implement Article 11.

This article describes current cigarette labeling policies implemented in LAC countries and the progress achieved in light of the FCTC. It also reports on tobacco industry interference, primarily by British American Tobacco (BAT) and Philip Morris International (PMI), the two transnational tobacco companies that have the greatest market share in the region, as well as their local subsidiaries.

Material and Methods

This is a cross-country, comparative analysis of HWLs printed on cigarette packages, as well as other important characteristics of cigarette package labeling, among the 33 countries of LAC. Information collected for this research came from governmental regulations on packaging and labeling for tobacco products of each of the 33 countries, tobacco industry corporate social responsibility reports, and cigarette packages sold in the participating countries.

Tobacco labeling legislation

We reviewed current tobacco control legislation (e.g., laws, executive decrees, ministerial resolutions, etc.) as of August, 2010 for the 33 LAC countries (Table II) available at the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO)'s legislation database PATIOS http://www.paho.org/tobacco/PatiosHome.asp. We analyzed mandatory HWLs printed on tobacco products, other warnings and messages, removal of misleading information, tobacco constituents and emissions labeling, and any other labeling regulations required by the government.

Tobacco industry reports

We analyzed information on cigarette labeling in the "social reports" published by BAT's affiliates in some LAC countries (Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Peru, Trinidad & Tobago, and Venezuela), which are part of their corporate social responsibility campaign, and are available at the BAT website http://www.bat.com/global (accessed between July 2007 and May 2010).

Cigarette packages repository

We collected 200 cigarette packages from 27 LAC countries through PAHO and the Comité Latino Americano Coordinador del Control del Tabaquismo (CLACCTA, Latin American Coordinating Committee on Smoking Control), the Latin America network of tobacco control researchers and advocates, maintained by the InterAmerican Heart Foundation. The cigarette packages are from different brand families belonging to the primary tobacco companies in each country, which are part of a collection maintained at Roswell Park Cancer Institute at: http://www.tobaccolatinamerica.org.

Results

Packaging and labeling policies

Following the Guidelines for implementing FCTC Article 11,7 the information is presented under the three subareas.

Health warning labeling

We located local regulations related to packaging and labeling on cigarettes for 19 of 20 countries in Latin American (all except Haiti), and 7 out of 13 non-Latin Caribbean countries (Table II). While we did not locate regulations for Antigua & Barbuda, Barbados, Belize, Saint Kitts & Nevis, Saint Vincent & the Grenadines, and Suriname, cigarette packages from those countries did have a single text-only warning as recommended by the CARICOM (the Caribbean Community) Bureau of Standards.63

Style

Most of the countries in the region (n=21) have text-only warnings on tobacco products (Table II). Following Canada's example (2001), seven Latin American countries adopted a combination of text and pictorial-based HWLs: Brazil (2002), Venezuela (2004), Uruguay (2006), Chile (2006), Panama (2006), Peru (2009), and Colombia (2010). In addition, Bolivia, Mexico, and Paraguay have passed legislation mandating pictures as part of their health warnings to be implemented by 2010. Honduras will follow suit in 2011. The seven countries that have implemented graphical warnings have adopted different types of photographs including diseased body parts, symbolic images (an ABSTRACT representation of a condition), and testimonial pictures (image of a face with or without personal identifying information) (Figure 1).

Number of warning messages and rotating system

Almost half of the LAC countries (n=19) have only one warning message printed on all cigarette packages. The other 17 countries have more than one message, ranging from 2 in Ecuador to 12 in Jamaica (Table II). Uruguay has adopted four sets of multiple and concurrent pictorial warnings (in 2006, 2007, early 2009, and late 2009), Brazil has adopted three sets (in 2002, 2004, and 2009), and so Panama (in 2006, 2009, and 2010) and Venezuela implemented two sets (in 2005 and 2009). Since 2006, Chile has a pair of two warnings (one pictorial in the front and one text-only in the back) printed at the same time in all cigarette packs and a new pair is introduced every year (4th set in 2009).

Location and size

In almost half of the LAC countries (n=17) HWLs mostly appear on the lateral side of the packs or less frequently, in the back (BAT voluntary). The rest of the countries (n=15) have different regulations, ranging from both main sides (e.g., front and back) and lateral side to only one main side, which is generally the back. The size (measured as a percentage of the principal display areas) ranges from 80% of both front and back in Uruguay (Figure 1) to 25% of the front in Guatemala (Table II).

Message content

Almost half (n=16) of the LAC countries have a weak and unspecific warning label message that only warns about the danger or risk to health similar to the 1966 US warning "Caution: Cigarette Smoking May be Hazardous to Your Health". Almost half (n=15) require warning label messages with themes related to specific diseases and/or other health effects or conditions (Table III). The 2009 Venezuelan's warnings also include a logo with the message "Venezuela Libre de Humo de Tabaco" Smokefree Venezuela (Figure 1), which may help promote the public support of the adoption of smokefree policies in the country. A toll-free telephone "quit line" number is required in Brazil, Uruguay, and Mexico. In addition, the Uruguayan's cigarette packages include a website address where smokers can get information on smoking cessation (Figure 1). Honduras and Trinidad & Tobago have not specified the message content of their HWLs as of August, 2010. Despite recommendations of Article 11's Guidelines, as of August 2010, no countries in LAC had adopted non-health messages such as the adverse economic or social outcomes, the environmental impact of tobacco use, or tobacco industry practices.

Almost a third of the LAC countries (n=10) require a marker word in capital letters, sometimes in a different color, at the beginning of the warning, which may draw the reader's attention to the message.64 Words used include "ADVERTENCIA" warning, "PELIGRO" danger, and "CUIDADO" careful. In Brazil the third set of pictorial warnings use the name of a disease such as "GANGRENA" gangrene.

Language

Except in Haiti, where HWLs are written in two languages (French and Creole), in the rest of LAC countries HWLs are written in only one language, either Spanish (most of the Latin American countries), Portuguese (only in Brazil), English (most of the CARICOM countries), or Dutch (only in Suriname) (Table II). However, other languages are spoken and officially recognized in four countries, Bolivia (Quechua or Aymara), Guatemala (distinct Mayan languages), Peru (Quechua or Aymara), and Paraguay (Guarani).

Source attribution

Although not a requirement of Article 11, more than half (n=20) countries attribute their warnings to either a national health authority or a legal provision. Health agencies include the Minister of Health (e.g., Barbados), the Institute for the Prevention of Alcohol and Drugs Addiction (e.g., Honduras), Minister of Public Health and Social Welfare (e.g., El Salvador), and the Chief Medical Officer (e.g., Jamaica). Costa Rica is the only country that attributes their warnings to a specific legal provision. The use of source of attribution can increase credibility in some countries but also can reduce the impact of the warning if they are too big.7

Removal of misleading information

Following FCTC Article 11's Guidelines, thirteen LAC countries have banned brand descriptors with references to implied harm reduction such as "light", "mild" or "low-tar." In addition, Bolivia has banned claims of additive-free, 100% natural, or organic tobacco; Brazil and Uruguay have banned the use of numbers as brand descriptors; and Uruguay has banned the use of colors to identify different cigarette types within a brand family (Table II). Colombia has banned the display of the expiration date, which can mislead consumers into think that there is a safe time to consume tobacco.7

Toxic constituents and emissions labeling

Toxic constituent information is required by law or voluntarily displayed by tobacco companies in 24 LAC countries (Table II). Cigarette packs in LAC have two types of constituent labeling: quantitative and qualitative. Quantitative disclosure involves printing the yields of different substances such as tar, nicotine, and carbon monoxide, which in 9 countries is required by law. Nine countries require a legend (lateral or on the back), with qualitative information on toxic constituents (e.g., tar, nicotine, and CO) as recommended by the Guidelines of FCTC's Article 11. Bolivia, Chile, Mexico, Peru, and Uruguay also disclose information on carcinogens other than tar (e.g., arsenic, cadmium and polonium). Mexico and Peru also provide information on other toxic substances, such as cyanide, or additives such as ammonia (Table II). Uruguayan cigarette packs require the skull-and-crossbones picture with the legend "Toxic Product", an internationally recognized symbol of poisonous substances (Figure 1). Bolivia and Panama are the only countries in the region that have banned the printing of the yields of tar, nicotine, and carbon monoxide that can be deceptive to the consumers as suggested by the Guidelines.7

The tobacco industry interference

Tobacco company arguments and strategies to oppose the implementation of effective cigarette labeling policies are similar across LAC and around the world.1 Arguments used include: warnings do not work; smokers already know the risks and therefore are not necessary; pictorial-based warnings harass and scare smokers; new warnings would cost too much money to implement; the timeline for implementation is too short and will take much more time; the industry does not have the technology necessary to implement the regulations. Tobacco companies have been using strategies to prevent the approval of laws or to weaken their provisions, as well as to delay implementation of strong HWLs and other effective labeling policies.

Preventing stronger policies

Voluntary measures

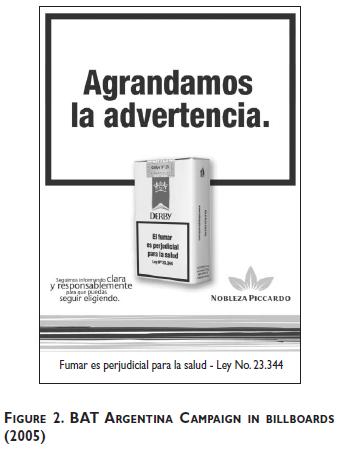

In 2005, BAT Argentina increased the size (up to 30% in the back) of the weak and unspecific only-text warning label "Fumar es perjudicial para la salud" Smoking is harmful to health. The company launched a campaign on billboards claiming "We increased the health warning label. We continue to inform clearly and responsibly so you can continue to choose. Nobleza Piccardo" (Figure 2).65 Similar measures were developed by BAT in Colombia,66 Honduras,67,68 Costa Rica,69 and Trinidad & Tobago.70

Tobacco companies also voluntarily print the yields of tar, nicotine, and carbon monoxide on cigarette packs potentially substitute for misleading descriptors such as "light", "ultra-light" and "low-tar" in several countries (n=10).

Lobby legislative and executive authorities

In 1986, the Congress of Argentina passed a very weak national law that established the current text-only warning label printed on all cigarette packs. However, the original draft of the bill required stronger message content.71 In 1992, BAT and PMI managed to get the presidential veto to a comprehensive law that Congress had approved and that would have resulted in new, rotating HWLs.71

Weakening new legislation: Agreement with health authorities

In 2004, BAT & PMI Mexico signed an agreement with the Secretary of Health of Mexico to increase the size of the HWLs from 25 to 50% of the back of the cigarette packages, under the condition that pictures would be excluded. In addition, they agreed to place a lateral warning reading "Currently there is no cigarette that reduces health risks" apparently to prevent the banning of brand descriptors (as required by the FCTC) that continued to appear on Mexican cigarette packs. Finally, the companies decided to include an onsert in 25% of the packs of each brand sold in the country with "health information" that was technical and difficult to read because of the small font size.72,73

Undermining the implementation

In 2006, before the first pictorial warning label appeared in Chile, BAT Chile began to give away metallic cigarette package covers that could be used to stick the packs inside and which would hide the warning.74 In addition, BAT Chile launched new formats of packages ("book pack design") that display two additional surfaces in the interior of the pack and break the warning.75 Stickers with cartoon faces to be used to cover the pictorial warning appeared in retail stores as well.

Delaying implementation: Litigation

Tobacco companies have litigated against the new cigarette labeling policies in Uruguay, Brazil, and Paraguay to stop or delay the implementation of pictorial warnings. As of August, 2010 the cases are pending in Brazil and Uruguay.

After the approval of the third set of warning labels in Brazil, four injunctions were filed against the Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA, National Agency of Health Surveillance). In December 2008, the tobacco industry trade unions from the State of Rio Grande do Sul (Sinditabaco/ RS) and the State of Rio de Janeiro (Sinditabaco/RJ) filed two injunctions against the new set of warning labels. In March 2009, Souza Cruz (BAT Brazil) filed a new injunction while the Public Minister of the State of Santa Catarina had done the same earlier the same year. After a short period of delay, the Court dismissed both cases and the new warnings began to appear in April 2009. However, the companies appealed to the Supreme Court where the final ruling is pending as of August, 2010.76,77 Arguments used were that the images did not represent the smoking associated risks, they may confuse and misinform the population, and that ANVISA should have used real images. In addition they claimed that the pictures hurt human dignity.

In September 2008, BAT Uruguay filed a complaint against Ministerial Ordinance 51456 that had been enacted by the Minister of Health of Uruguay on August 18, 2008, which among other provisions, banned tobacco companies from having more than one presentation for each brand. In other words, the law would allow only one type of Marlboro or other brand name. On October 1, 2008 the case was dismissed by the Court. According to a local newspaper, in October 2009, Montepaz, Abal Hermanos (PM Uruguay), and BAT, the three tobacco companies that share the market in Uruguay, filed a complaint against the Executive Decree that increased the size of the HWLs from 50 to 80 % of the total display areas. The companies called the decree "irrational, illegal, insensate, overbearing, and arbitrary."78 On February 19, 2010, PMI sued the government of Uruguay before the International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) alleging that the country requirements that banned the use of more than one brand presentation infringed a bilateral Switzerland-Uruguay investment treaty.79 According to its website "the primary purpose of ICSID is to provide facilities for conciliation and arbitration of international investment disputes."80 According to a representative from Abal Hermanos/PM Uruguay, their goal is "to repair the damage from regulatory measures taken by the Executive Branch during the last two years that harmed PMI investments in the country and curtailed the company's right to use its registered brands, in frank violation of Uruguay's international obligations" and " to suspend the application of the recently approved regulations."79 As of August 2010, the final ruling was pending.

On December 26, 2009 the Supreme Court of Justice of Paraguay declared null the Ministerial Resolution enacted by the Minister of Health and Social Welfare in May 2009, which sought the implementation of new warning labels in the country. The ruling was a result of an injunction presented by the Tobacco Union of Paraguay (on behalf of representatives of all tobacco companies in Paraguay) on the grounds of unconstitutionality.81 However, in March, 2010, the President issued a Decree to comply with new HWLs according to the FCTC.46

Discussion

In 2002, Brazil became the first country within the region to implement pictorial-based HWLs, which it did before the WHO FCTC entered into force in February 2005. Since then, and in accordance with the recommendations of the WHO FCTC's Article 11 Guidelines, six other LAC countries followed suit and four more have approved legislation to be implemented during 2010 and 2011.

Our results indicate that around 27% (9/33) of LAC countries have implemented the minimum provisions of Article 11 in all three sub-policy areas: 1) pictorial warning labels, at least 50% of main faces, specific health effects, rotating, principal/s language/s; 2) ban of brand descriptors; and 3) qualitative content and emissions label, while 12% (4/33) adopted either one or two of them. However, the majority of LAC countries (n=20) require less than the minimum provisions or none.

Our results also indicate that cigarette package warning content and style of presentation varies significantly across countries. The effectiveness of different approaches is only beginning to be studied. A study conducted as part of the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project, evaluated the impact of HWLs in Uruguay, Brazil and Mexico and found that Uruguayan smokers were more likely than Brazilian or Mexican smokers to notice regularly HWLs, probably due to Uruguayan warnings were printed in both main faces, whereas Brazilian and Mexican were only on the back. Furthermore, this study indicates that Brazilian warnings had a greater cognitive and behavioral impact than either Mexican or Uruguayan, with Mexican text-only labels doing equal or better than Uruguayan labels. This result suggests that the ABSTRACT representation of Uruguayan pictorial HWLs is not as effective as the Brazilian strategy. Finally, the Brazilian pictorials had an inverse association with educational achievement, suggesting that style of pictures could address literacy issues.82 The WHO/CDC Global Adult Tobacco Survey conducted in Brazil83 (2008) and Uruguay84 (2009) showed that 65% and 45% respectively of current smokers thought about quitting because of a warning label.

A few countries have developed and adopted synergistic measures to enhance the impact of their HWLs, such as mass media campaigns and mandating the placement of the same health warnings on tobacco advertising including point-of-sale. For example, in 2002, the Brazilian government launched 2 TV spots with the stories of "Euclide" and "Renata" victims of larynx cancer and abortion respectively to promote two of the new pictorial warnings.85 Since 2006, when it was implemented the first testimonial HWL in Chile86 (Figure 1), the Minister of Health of Chile has been launching the new picture in a press conference contributing to the publicity of the health warning. In addition to the cigarette packs, the Chilean law mandates the placement of the same health warning label in 50% of all graphic tobacco advertising (counter-advertising) such as billboards and point-of-sale displays.18 In Brazil and Uruguay, warnings are also present at point-of-sale.57

In 2009, Uruguay became the first country in the world to limit brands to only one presentation per brand name (e.g., Marlboro), which moves in the direction of plain packaging (e.g., completely removal of brand imagery including color).87 This regulation aims to help eliminate misleading consumers about relative risk of products. As of August, 2010, the tobacco industry was not able to successfully challenge this significant progress.

In addition to the information mandated by law, tobacco companies generally print other messages on the cigarette packages either to compete with the mandated health warnings or to mislead the consumers. Legends with a reference to an expiration date such as "Better before"... are printed on several countries of the region voluntary by the tobacco industry. Only Colombia followed recommendations of Article 11's Guidelines and banned it. Underage warnings such as "Only for adults" or "Underage sale prohibited" are also printed voluntarily in cigarette packs from several LAC countries. These legends are part of the tobacco industry's "youth smoking prevention" programs developed in Latin America during the 1990s to portray cigarettes as an adult product while continue marketing to young people.88

In 2009, an intergovernmental initiative was developed within the countries from the MERCOSUR (the trade agreement of South America) with the goal of creating and maintaining an electronic-based bank of pictorial warnings, which are available for any country of the region seeking to implement such policy: http://www.cictmercosur.org/esp/index.php The Convention Secretariat, following a decision by the COP3 and with the technical assistance of WHO's Tobacco Free Initiative, established a central international database of HWLs, which is available at: http://www.who.int/tobacco/healthwarningsdatabase/en/index.html.

Conclusions

Since 2002, important progress has been achieved in the region. However, only Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela meet FCTC's Article 11 minimum requirements. Furthermore, as of August, 2010, 11 countries that are Parties to the WHO FCTC have passed the deadline of 3 years between ratifying and implementing Article 11. The tobacco industry has used predictable arguments and strategies to block, undermine and delay the effective implementation of Article 11. Policymakers who want to implement effective labeling policies in their countries need to be aware and anticipate tobacco industry tactics to counteract them, prevent loopholes in the regulations, and use scientific evidence and experience from other countries.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute (FAMRI) and the National Cancer Institute grant CA-87472 and program project grant P01 CA138389 "Effectiveness of Tobacco Control Policies in High vs. Low Income Countries" to Roswell Park Cancer Institute. The funding agencies played no role in the conduct of the research or preparation of the manuscript.

We would like to thank Rob Cunningham and James Thrasher for their helpful comments on this article.

Declaration of conflicts of interest

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Chapman S, Carter SM. "Avoid health warnings on all tobacco products for just as long as we can": A history of Australian tobacco industry efforts to avoid, delay and dilute health warnings on cigarettes. Tob Control. 2003 Dec; 12 Suppl 3: iii13-22. [ Links ]

2. World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2009: Implementing smoke-free environments. Geneva: WHO; 2009. [ Links ]

3. Wakefield M, Morley C, Horan JK, Cummings KM. The cigarette pack as image: New evidence from tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2002 Mar; 11 Suppl 1: I73-80. [ Links ]

4. Vincent AL. Advertencias en las cajetillas de cigarrillos en América Latina y el Caribe Warnings on cigarette packs in Latin America and the Caribbean. Bol Oficina Sanit Panam. 1993 Jun; 114(6): 492-501. [ Links ]

5. Aftab M, Kolben D, Lurie P. International cigarette labelling practices. Tob Control. 1999 Winter; 8(4):368-72. [ Links ]

6. World Health Organization. Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: WHO; 2003. Accessed 2010, March 20 Available in: http://www.who.int/tobacco/framework/download/en/index.html [ Links ]

7. World Health Organization. Guidelines for implementation of Article 11 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (packaging and labelling of tobacco products). Durban; 2008 Nov 17-22. Accessed 2010, March 20 Available in: http://www.who.int/fctc/guidelines/article_11/en/index.html [ Links ]

8. Personal communication Lalla-Rodrigues D. Standards on labelling of cigarette packages in Antigua & Barbuda. St John's: ABBS; 2010. [ Links ]

9. Argentina Law 23.344 «Restricciones en la publicidad de tabacos, cigarrillos, cigarros u otros productos destinados a fumar- leyenda que deberán llevar los envases»; 1986. [ Links ]

10. Bahamas health services (tobacco advertising and sales) rules; 1977. [ Links ]

11. Personal communication Maloney A. Standards on labelling of cigarette packages in Barbados. Saint Michael: Barbados National Standards Institution (BNSI); 2010. [ Links ]

12. CTC (Caribbean Tobacco Company Ltd). Tobacco use & health. 2010 Accessed 2010 March 3. Available in: http://ctcbelize.com/health.shtml [ Links ]

13. President of Bolivia. Supreme Decree N° 29376 Reglamento de la Ley N° 3029 de 22 de abril de 2005 de ratificación del "Convenio Marco para el Control del Tabaco"; 2007. [ Links ]

14. Minister of Health and Sports, Minister of Education, Minister of Economy and Finances of Bolivia. Multiministerial Ruling N° 0003 "Reglamento especifico para la administración de la Ley N° 3029 del Convenio Marco para el Control del Tabaco (REAT)"; 2009. [ Links ]

15. Brazil National Health Surveillance Agency (ANVISA). Ruling N° 104; 2001. [ Links ]

16. Brazil National Health Surveillance Agency (ANVISA). Ruling N° 335; 2003. [ Links ]

17. Brazil National Health Surveillance Agency (ANVISA). Ruling N° 54; 2008. [ Links ]

18. Chile Law N° 20.105 "Modifica la Ley N° 19.419, en materias relativas a la publicidad y el consumo del tabaco"; 2006. [ Links ]

19. Minister of Health of Chile. Decree N° 95 "Establece advertencia para envases y acciones publicitarias de productos hechos con tabaco"; 2006. [ Links ]

20. Minister of Health of Chile. Decree N° 128 "Establece advertencia para envases y acciones publicitarias de productos hechos con tabaco"; 2007. [ Links ]

21. Minister of Health of Chile. Decree N° 69 "Establece advertencia para envases y acciones publicitarias de productos hechos con tabaco"; 2008. [ Links ]

22. Minister of Health of Chile. Decree N° 61 "Establece advertencia para envases y acciones publicitarias de productos hechos con tabaco"; 2009. [ Links ]

23. Colombia Law N° 1335 "Disposiciones por medio de las cuales se previenen danos a la salud de los menores de edad, la población no fumadora y se estipulan políticas públicas para la prevención del consumo del tabaco y el abandono de la dependencia del tabaco del fumador y sus derivados en la población colombiana"; 2009. [ Links ]

24. Ministry of Social Protection of Colombia. Ruling N° 003961 "Por la cual se establecen los requisitos de empaquetado y etiquetado del tabaco y sus derivados"; 2009. [ Links ]

25. Costa Rica Law N° 7.501 "Regulación del fumado"; 1995. [ Links ]

26. Minister of Health of Cuba. Resolución Ministerial N° 275/2003 "Reglamento para el registro sanitario de los productos manufacturados del tabaco"; 2003. [ Links ]

27. Dominica Bureau of Standards (DBOS). Specification for labelling of commodities - retail packages of cigarettes dns 2: Part 6; 2002. [ Links ]

28. Dominican Republic Law N° 48; 2000. [ Links ]

29. Ecuador "Ley orgánica reformatoria a la ley orgánica de defensa del consumidor"; 2006. [ Links ]

30. Congress of El Salvador. Decreto legislativo N° 955 "Código de Salud"; 1988. [ Links ]

31. Grenada Bureau of Standards (GDBS). Gds 1: Part 6: Labelling of retail packages of cigarettes; 1997. [ Links ]

32. President of Guatemala. Acuerdo Gubernativo N° 426-2001 "Reglamento para la regulación, aprobación y control de la publicidad y lugares de consumo de productos relacionados con el tabaco"; 2001. [ Links ]

33. Guyana National Bureau of Standards (GNBS). Specification for labeling of commodities. Part 3: Labeling of retail packages of cigarettes; 2004. [ Links ]

34. Instituto Hondureño para la Prevención del Alcoholismo Drogadicción y Farmacodependencia, (IHADFA). Ley especial para el control del tabaco; 2010. [ Links ]

35. Jamaica Bureau of Standards. Jamaican standard specification for the labeling of commodities part 25: Labeling of cigarette packages; 2006. [ Links ]

36. Congress of Mexico Ley general para el control del tabaco; 2008. [ Links ]

37. Secretary of Health of Mexico "Acuerdo mediante el cual se dan a conocer las disposiciones para la formulación, aprobación, aplicación, utilización e incorporación de las leyendas, imágenes, pictogramas, mensajes sanitarios e información que deberá figurar en todos los paquetes de productos del tabaco y en todo empaquetado y etiquetado externo de los mismos". DOF; 2009. [ Links ]

38. President of Mexico. Reglamento de la ley general para el control del tabaco; 2009. [ Links ]

39. Nicaragua Law N° 224 "Ley de protección de los derechos humanos de los no fumadores"; 1996. [ Links ]

40. President of Nicaragua. Decreto N° 29-2000 "Reglamento de la Ley N° 224, ley de protección de los derechos humanos de los no fumadores"; 2000. [ Links ]

41. Congress of Panama Law N° 13 "Que adopta medidas para el control del tabaco y sus efectos nocivos en la salud"; 2008. [ Links ]

42. President of Panama. Executive Decree N° 230 "Que reglamenta la Ley 13 de 24 de enero de 2008 y dicta otras disposiciones"; 2008. [ Links ]

43. Minister of Health of Panama. Resolución 809; 2008. [ Links ]

44. Minister of Health of Panama. Resolución 868; 2009. [ Links ]

45. Minister of Health of Panama. Resolución 153; 2010. [ Links ]

46. President of Paraguay. Presidential Decree N° 4.106 "Por el cual se reglamenta el cumplimiento del artículo 11 de la Ley N° 2969106, que aprueba el Convenio Marco de la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) para el Control del Tabaco"; 2010. [ Links ]

47. Congress of Peru Law N° 28.705 "Ley general para la prevención y control de los riesgos del consumo de tabaco"; 2006. [ Links ]

48. President of Peru. Decreto Supremo N° 015-2008-sa "Reglamento de la ley N° 28705, ley general para la prevención y control de los riesgos del consumo del tabaco"; 2008. [ Links ]

49. Minister of Health of Peru. Resolucion Ministerial N° 899-2008 "Normativa gráfica para el uso y aplicación de las advertencias sanitarias en envases, publicidad de cigarrillos y de otros productos hechos con tabaco"; 2008. [ Links ]

50. Minister of Health of Peru. Resolucion Ministerial N° 097-2010; 2010. [ Links ]

51. Congerss of Peru Law N° 29.517 "Ley que modifica la ley N° 28705, ley general para la prevención y control de los riesgos del consumo del tabaco, para adecuarse al Convenio Marco de la Organización Mundial de la Salud para el Control del Tabaco"; 2010. [ Links ]

52. Saint Lucia Bureau of Standards (SLBS). Slns 17: Labelling of retail packages of cigarettes; 1992. [ Links ]

53. ZIGSAM - The Austrian cigarette collection. Identifying cigarettes: Health warnings. 2010 Accessed 2010 March 3. Available in: http://www.zigsam.at/R_Identify.htm [ Links ]

54. Personal communication Pawirodinomo M. Standards on labelling of cigarette packages in Suriname. Paramaribo: SSB; 2010. [ Links ]

55. Parliament of Trinidad & Tobago Tobacco Control Act. 2010. Accessed 2010 February 17. Available in: http://www.ttparliament.org/publications.php?mid=28&id=545. [ Links ]

56. Minister of Health of Uruguay. Ministerial Ordinance N° 514; 2008. [ Links ]

57. Congress of Uruguay Law N° 18.256 "Control del tabaquismo"; 2008. [ Links ]

58. Minister of Health of Uruguay. Decree N° 284 "Reglamenta la Ley N° 18.256"; 2008. [ Links ]

59. Cabinet of Uruguay. Decree N° 287/ 009; 2009. [ Links ]

60. Minister of Health of Uruguay. Ministerial Ordinance N° 466; 2009. [ Links ]

61. Ministry of Health of Venezuela. Ruling N° 110; 2004. [ Links ]

62. Ministry of Health of Venezuela. Ruling N° 056; 2009. [ Links ]

63. Caribbean Community Bureau of Standards. Requirements for the labeling of retail packages of cigarettes: Ccs 0026; 1992. [ Links ]

64. Mahood G. Canada's tobacco package label or warning system: "telling the truth" about tobacco product risks: WHO; 2003. [ Links ]

65. Simpson D. Argentina: Down Mexico way? Tob Control. 2006 Dec; 15(6):421. [ Links ]

66. BAT Colombia. Balance Social 2004/ 2005 Accessed 2010 March 15. Available in: http://www.batcolombia.com/oneweb/sites/BAT_6CFDZ6.nsf/vwPagesWebLive/DO6GU26E/$FILE/medMD7E7SNS.pdf?openelement. [ Links ]

67. BATCA, Tabacalera Hondureña. Balance social 2007/ 2008 Ciclo 1 Honduras; 2008 March. Accessed 2010 March 7; Available in: http://www.bat.com/group/sites/UK__3MNFEN.nsf/vwPagesWebLive/30B3A1E53F811B98C125763C004DE8F4/$FILE/Honduras%202007.pdf?openelement. [ Links ]

68. Revista Honduras Market. British American Tobacco Central America aumenta voluntariamente el tamaño de la advertencia sanitaria. 2005. Accessed 2010 March 9. Available in: http://revistamarket.com/edicion_nov_2_2005/batca/batca.html. [ Links ]

69. BATCA. Balance social 2006. Ciclo 2: Costa Rica; 2006. Accessed 2010 March 9. Available in: http://www.batcentralamerica.com/oneweb/sites/BAT_58VLSP.nsf/vwPagesWebLive/DO6HKK3Z/$FILE/medMD7BER85.pdf?openelement. [ Links ]

70. West Indian Tobacco. 2007 Annual Report; 2007 Accessed 2010 March 9. Available in: http://www.batcentralamerica.com/oneweb/sites/BAT_58VLSP.nsf/vwPagesWebLive/DO66BRC6/$FILE/medMD7DCU9S.pdf?openelement. [ Links ]

71. Sebrié EM, Barnoya J, Pérez-Stable EJ, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry successfully prevented tobacco control legislation in Argentina. Tob Control. 2005 Oct; 14(5):e2. [ Links ]

72. Sebrié E, Glantz SA. The tobacco industry in developing countries. BMJ. 2006 Feb 11;332 (7537): 313-4. [ Links ]

73. Sebrié E. Mexico: Backroom deal blunts health warnings. Tob Control. 2006 Oct;15 (5): 348-9. [ Links ]

74. Diputado Rossi criticó a Chile tabacos por promoción que regala cigarreras. Cooperativa.cl; 2006. Accessed 2010, March 9. Available in: http://www.cooperativa.cl/prontus_nots/site/artic/20060510/pags/20060510155028.html. [ Links ]

75. Araya E. Salud exige multa de 16 millones de pesos para empresa Chiletabacos. La Nación 2007. Accessed 2010, March 9. Available in: http://www.lanacion.cl/prontus_noticias/site/artic/20070129/pags/20070129213407.html. [ Links ]

76. Brazil National Cancer Institute (INCA). Justiça nega liminar em ação contra imagens de advertência em maços de cigarro. 2009. Accessed 2010, March 9. Available in: http://www.inca.gov.br/releases/press_release_view.asp?ID=1990. [ Links ]

77. Formenti L. TRF derruba liminar contra nova advertência em cigarro. Estadaocombr; 2009. Accessed 2010, March 20. Available in: http://www.estadao.com.br/noticias/geral,trf-derruba-liminar-contra-nova-advertencia-em-cigarro,348511,0.htm. [ Links ]

78. Pérgola G. Las tabacaleras recurren decreto del ejecutivo Tobacco companies appealed against the presidential decree. El País Digital. Montevideo; 2009. Accessed 2009, October 4. Available in: http://www.elpais.com.uy/091004/pecono-445826/actualidad/las-tabacaleras-recurren-decreto-del-ejecutivo. [ Links ]

79. Tiscornia F. Tabacalera demanda a Uruguay en el exterior Tobacco company sues Uruguay abroad. El País Digital. Montevideo; 2010. Accessed 2010, March 20. Available in: http://www.elpais.com.uy/100227/pecono-473697/economia/tabacalera-demanda-a-uruguay-en-el-exterior. [ Links ]

80. International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). 2010 Accessed 2010, March 20. Available in: http://icsid.worldbank.org/ICSID/FrontServlet [ Links ]

81. Supreme Court of Justice of Paraguay. Acuerdo y Sentencia N° 916; 2009. [ Links ]

82. Thrasher JF, Villalobos V, Szklo A, Fong GT, Pérez C, Sebrié E, et al. Assessing the impact of cigarette package health warning labels that include different styles of pictorial imagery and text: A cross-country comparison of adult smokers in Brazil, Uruguay, and Mexico. Salud Publica Mex 2010;52(suppl 2):S204-S213. [ Links ]

83. INCA, IBGE, WHO, CDC. Global adult tobacco survey (GATS). Pesquisa especial de tabagismo (Petab): Executive summary Brazil 2008. Rio de Janeiro; 2009. Accessed 2010, March 20. Available in: http://new.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1818&Itemid=1187. [ Links ]

84. WHO, CDC. Global adult tobacco survey (GATS): Fact sheet Uruguay 2009; 2010. Accessed at 2010, March 20. Available in: http://new.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1818&Itemid=1187. [ Links ]

85. Brazil National Cancer Institute (INCA). 2010 Accessed 2010 March 20. Available in: http://www1.inca.gov.br/tabagismo/frameset.asp?item=multimidia&link=videos.swf [ Links ]

86. Antes de fumar, mire en su cajetilla a Don Miguel Before smoking look at Don Miguel on the pack. La Nación; 2006. Accessed 2010, March 20. Available in: http://www.lanacion.cl/prontus_noticias/site/artic/20061112/pags/20061112212105.html. [ Links ]

87. Hammond D. "Plain packaging" regulations for tobacco products: The impact of standardizing the color and design of cigarette packs. Salud Publica Mex 2010;52(suppl 2):S224-S230. [ Links ]

88. Sebrié EM, Glantz SA. Attempts to undermine tobacco control: Tobacco industry "Youth smoking prevention" Programs to undermine meaningful tobacco control in Latin America. Am J Public Health. 2007 Aug; 97(8): 1357-67. [ Links ]

Received on: March 26, 2010

Accepted on: June 9, 2010

Address reprint requests to: Ernesto M Sebrié, MD, MPH. Roswell Park Cancer Institute. Elm & Carlton Streets. 14263 Buffalo, NY, USA.

E-mail: ernesto.sebrie@roswellpark.org