Introduction

Lipedema is a fibrotic loose connective tissue disease1, intimately related to other connective tissue diseases targeting the skin, muscles, ligaments, tendons, fascia, joints, and even the veins and potentially the arteries. This condition was described for the first time by Hines and Allen in 19402. Lipedema is a hereditary condition, probably with autosomal dominance inheritance with sex limitation3, which mainly affects women in the family but is not exclusive, as it can also affect men2, including children3. For those of us in the field of lipedema, experiences can be wide and can include rare conditions such as hyperpulsatilities that must not be confused with aneurysmal disease. Lipedema predisposes to the accumulation of fat under the skin, as well as a limited ability to develop muscle, both to varying degrees among individuals. The accumulation of fat under the skin provokes greater laxity of the tissues involved (skin flaccidity), mainly in the legs and hips, but not limited since it can also affect the arms and torso. Skin laxity predisposes to the appearance of bruises, a common cause of consultation. Lipedema distributes fat tissue, mostly in the core areas of the body, and it frequently respects hands and feet. It is associated with vascular diseases, mostly vein and lymphatic disease2; therefore, it should be considered a vascular disease.

Lipedema has no symptoms but signs with a broad clinical spectrum which makes diagnosis difficult, remaining nowadays clinical. There are some previously well-known medical imaging techniques proposed, such as computed tomography scan, magnetic resonance imaging, ultrasonography, and lymphangiography, but none of them are actually practical to guide the diagnosis, because none of them are focused on the pathogenesis of the condition4. Hines and Allen established clinical findings in 119 cases with enlargement of the legs, pain, pitting edema, varicose veins, and strong family history2. Differential diagnosis must be made with lymphedema, lipohypertrophy, and traditional obesity5.

Pathogenesis of this condition is not well understood, and will not be profoundly addressed in this article, given the lack of high-quality articles, and not considered necessary for the purpose of the present study. Atzigen and cols found in histological studies that epidermal thickness was present in lipedema and lymphedema but not in normal fat tissue or lipohypertrophy, but adipocyte size was increased in lipedema and lypohypertrophy but only in advanced stages of lymphedema, concluding that well-established differences are present to the same extent, with remodeling of the extracellular matrix and fibrosis in secondary lymphedema and lipedema, related to collagen remodeling5. This has led to suspect that a lymphatic disorder is involved. Gene expression has been proven different between lipedema and lipodystrophy5,6.

The objective of this study is to draw the attention of the vascular specialist addressing this broad condition and to guide those who are beginning to understand this condition, grouping the criteria and purposing clinical criteria, expanding it with my personal experience.

Material and methods

A search was conducted by the first and only author using PubMed, Academia, Web of Science, and Cochrane to locate the most recent and most complete articles regarding the subject of lipedema (from 2018 onwards). Among the articles considered, only those that met the the correct metholodogical process and provided extensive information on clinical diagnostic criteria were taken as valid. The MeSH term used was Lipedema and/or Lipoedema.

To broaden the understanding of the disease, I included representative images of patients who accepted to participate in the study through their personal consultation photo gallery and signed the informed consent. Personal data was carefully omitted as part of the protection considered within the ethical principles involving studies in humans (Helsinki, 1975), not showing any other part of their bodies than their lower legs.

Studies selected

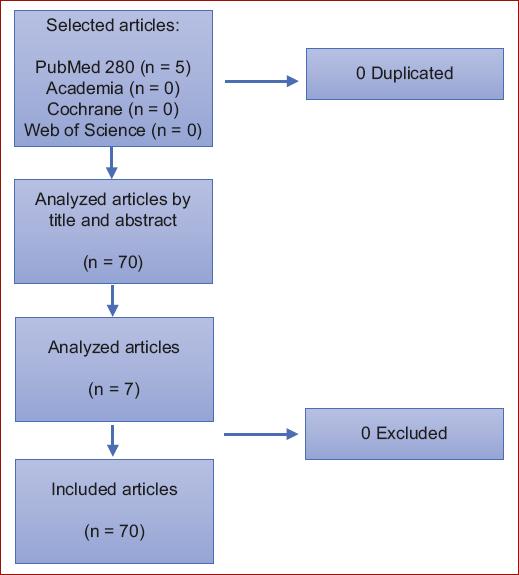

I decided to only select those articles with a proper methodological process focusing on broad information on the subject to comprehend the clinical basis. I decided to exclude those focused on specific ways of treatment above all those focused on fat removal. The main articles were revisions and prospective studies with a higher level of evidence (Fig. 1).

It is important to mention that the word lipedema is easily confused with lymphedema. Of twenty-nine results from Cochrane database with the word lipedema (four of them actually from lymphedema), I only selected three because the others focused on treatments; they were finally eliminated because they were trials published in https://clinicaltrials.gov. As for the word lipoedema, there were five articles, only two of them regarding lipedema, which were finally eliminated because they focused on treatment.

In the PubMed database, there were 289 results but most of them focused on treatment, limiting to prospective studies the number of articles diminished to seven randomized controlled trials (RCT) and seven systematic reviews, as well as three meta-analysis and 57 simple reviews. The articles were selected manually because of the content of each and used four of the systematic reviews and one of the meta-analyses. The RCTs and the other articles were excluded because they compare treatment techniques. In Academia, there were none. A manual search was considered necessary due to the lack of articles, especially those written decades ago, such as the pioneering research by Hines and Allen, as well as another written in Spanish and several others published before 2018. Three articles in Spanish were found but were ultimately excluded because they were related to treatment. References 1, 3, 7, 8, and 11 were obtained through the described methodological process; references 2, 4, 5, 9, and 10 were found manually.

Discussion

Clinical criteria for the diagnosis of lipedema do not exist, although Hines and Allen attempted to describe some in their pioneering article; these were very nonspecific and included a family history of similar leg appearance among women in their families, enlargement during menarche or menopause, pain in the lower extremities, presence of pitting edema or varicose veins2. Surprisingly, there is no study after this article (1949), trying to establish the clinical criteria for this condition, motivating the writing of this article.

Lipedema patients present signs and symptoms within a broad clinical spectrum, ranging from mild, barely perceptible forms to the most severe, deforming, and disabling forms, along with one or several other criteria (Table 1).

Table 1 CETIEV clinical criteria for lipedema1,8,9

| Major |

| Female |

| Direct family with a history of lipedema |

| Central distribution of body fat (see classification) |

| Skin laxity |

| Appearance of bruises (may occur after blows or spontaneously, i.e., without apparent cause) |

| Poor muscle development (especially in women) or inability to define body musculature (men) |

| Autonomic dysautonomia, dysfunctional autonomic response (READ), or dysfunctional response syndrome (REDIS) |

| Varicose veins or telangiectasias on medial or lateral genicular region, outer thighs including buttocks, and the ankles |

| Skin diseases such as livedo reticularis, eczema, and rosacea |

| Minor |

| Traditional biomechanical profile (sequence of images 1): |

| Pronator footprint with or without flat feet (some patients corrected arch in childhood) |

| Hallux valgus including quintus varus (or medial or lateral hyperkeratosis) |

| Valgus of the knees |

| Symptomatic dysmetria |

| Pelvic imbalance |

| Scoliosis or spondyloarthropathy |

| Tendency to develop sprains |

| Joint hyperlaxity |

| Direct family with a history of hernias (disc, abdominal wall, and hiatal) |

| Family with usual biomechanical profile |

| Painful lipomatosis |

Research protocols are required to accurately define these criteria and establish frequencies in populations with lipedema. We include READ or Autonomic dysautonomia or dysfunctional autonomic response as a diagnostic criterion because orthostatic intolerance, hypotension, and thermoregulations alterations are frequently present, and must be studied worldwide.

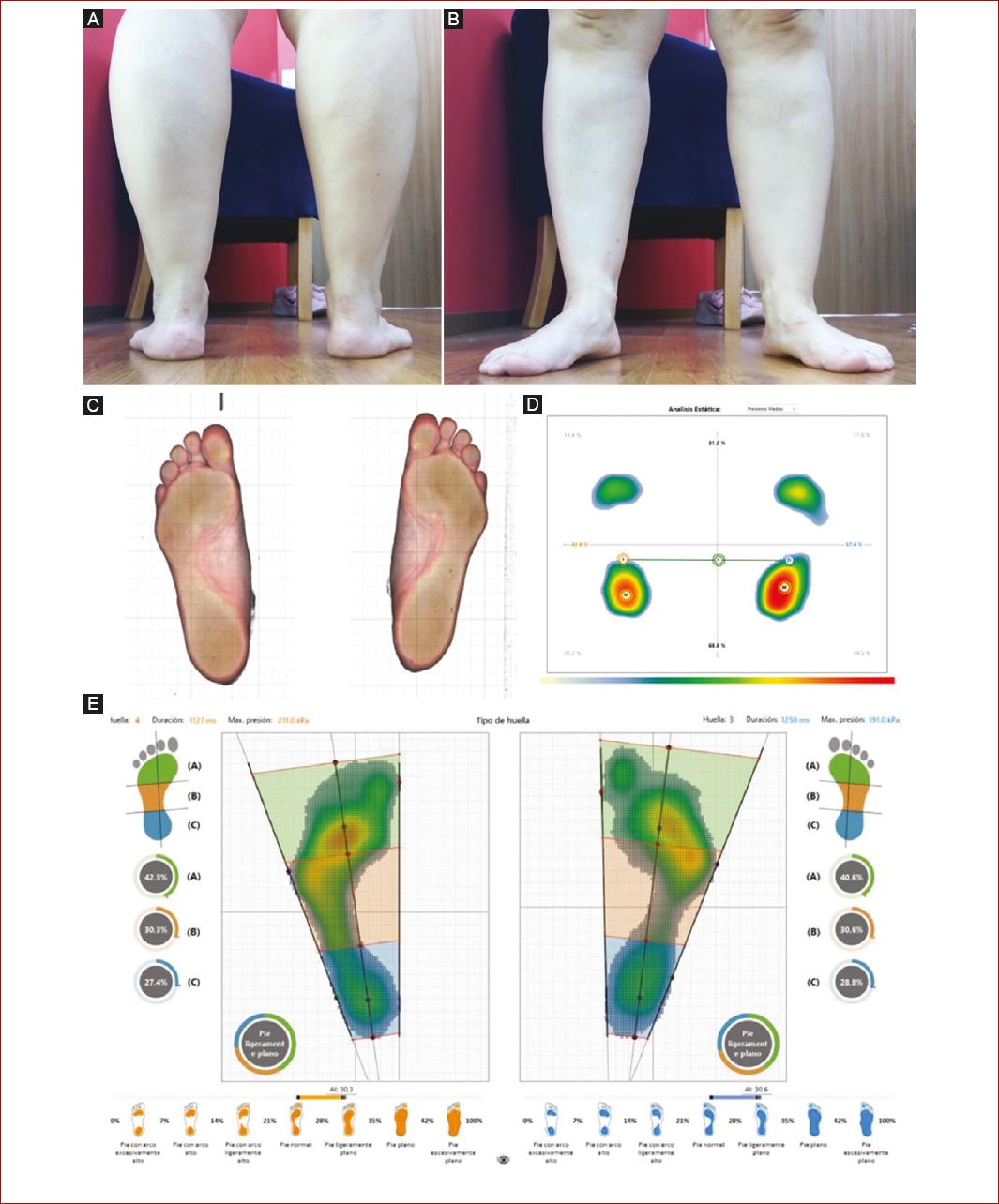

The diagnosis is clearly clinical and should be complex, since if we only consider body appearance based on the distribution of fatty tissue, we may exclude patients with mild physical changes. Besides, we do know that fat distribution can be acquired in later ages of life and be present mildly almost absent in younger patients. Therefore, I suggest establishing diagnostic criteria to guide our diagnostic and understanding of the disease to treat them as soon as possible and before permanent physical changes begin. I propose the diagnostic criteria in table 1 based on two international consensuses1,8, an article found manually9, and my own experience, grouping them into major and minor findings. Given the fact that lipedema has biomechanical abnormalities, establishing a biomechanical profile through complete baropodometry can help us define minor criteria (Fig. 2).

Figure 2 Photo gallery, digital plantoscopy, and static and dynamic baropodometry for biomechanical analysis of gait of a patient with lipedema, 39 years. A: posterior view of the appearance of the legs of a patient with lipedema, there can be seen the pronated position of the ankle, B: it can be seen the position in Valgo of the knees, which obliges to compensate by forefoot abduction on both of the legs, C: digital plantoscopy with a normal arc, it can be seen metatarsal collapse with clawed toes and hyperkeratosis on the metatarsals areas, mostly over the 2nd and the 5th metatarsals heads, Quintus Varo bilaterally, D: static baropodometry appears to have a high arch due to the pronation of the ankle, which relieves pressure from the external surface of the sole of the foot, E: dynamic baropodometry correlates better with plantoscopy although one must be careful because given that flatfoot pronates the ankle, it is frequent the algorithm concludes as a flatfoot when there is marked pronation of the ankle, that is one of the reasons to always compare with the plantoscopy and photo gallery.

Validated diagnostic criteria should be our first objective to achieve, mainly to at least differentiate it from lipohypertrophy, regular obesity, or lymphedema, especially when lipedema can degenerate into lymphedema coexisting with venous disease. Potentially, all these conditions are somehow related to connective tissue diseases. Considering that lower leg pain has a broad spectrum of etiologies, the same applies to the 70 differential diagnoses of leg edema10.

Lipedema has multiple ways of manifesting itself and can appear in all contexts of physical complexion (patients from very thin to all possible degrees of overweight), because lipedema is not necessarily related to overweight, so controlling weight in the traditional way has little or no effect on the results, mostly in older patients. The most commonly reported symptom in the literature is the thickened appearance of the limbs, mainly in the legs, often sparing the hands and feet. It is usually accompanied by evident laxity or flaccidity of the tissues (skin and adipose tissue), with little muscle development, presence of an orange peel appearance on the outer aspects of the thighs and the medial aspects of the calves (which can be present from a very young age but may also be absent), as well as being a site for the formation of spider veins or reticular veins. Livedo reticularis is a common finding1. Depending on the advance of the volume of the leg, fatty nodules can sometimes be felt under the skin, especially where there is more fatty volume and therefore flaccidity or laxity. In some patients, when accompanied by neuropathy, there may be pain, which is why sometimes is referred to as painful lipidosis. Tissue weakness can be widespread, as patients may have hernias in different parts of the body (spinal discs, hiatal in the stomach, umbilical, inguinal), as well as a predisposition to develop muscle injuries such as muscular tears and tendon injuries like sprains (Fig. 3). In some patients, the skin is so sensitive that bruises appear easily because of capillary fragility. One of the characteristics is that the distribution of the fat always respects the feet and hands of the patients unless lymphedema.

Figure 3 Bruises after a spontaneous sprain of a patient with lipedema, 39 years. A: same 39-year female patient who sprained the ankle after rotating the leg to get off a platform, there was no fall over the leg, there were no twisting or falling nor bending but a small subcutaneal hematoma formed provoking pain, B: result after 1-day treatment with V inverted technique compression bandages, C: after the first session of physiotherapy giving support to the ankle by kinesiologic tapes, physiotherapy is essential in the treatment.

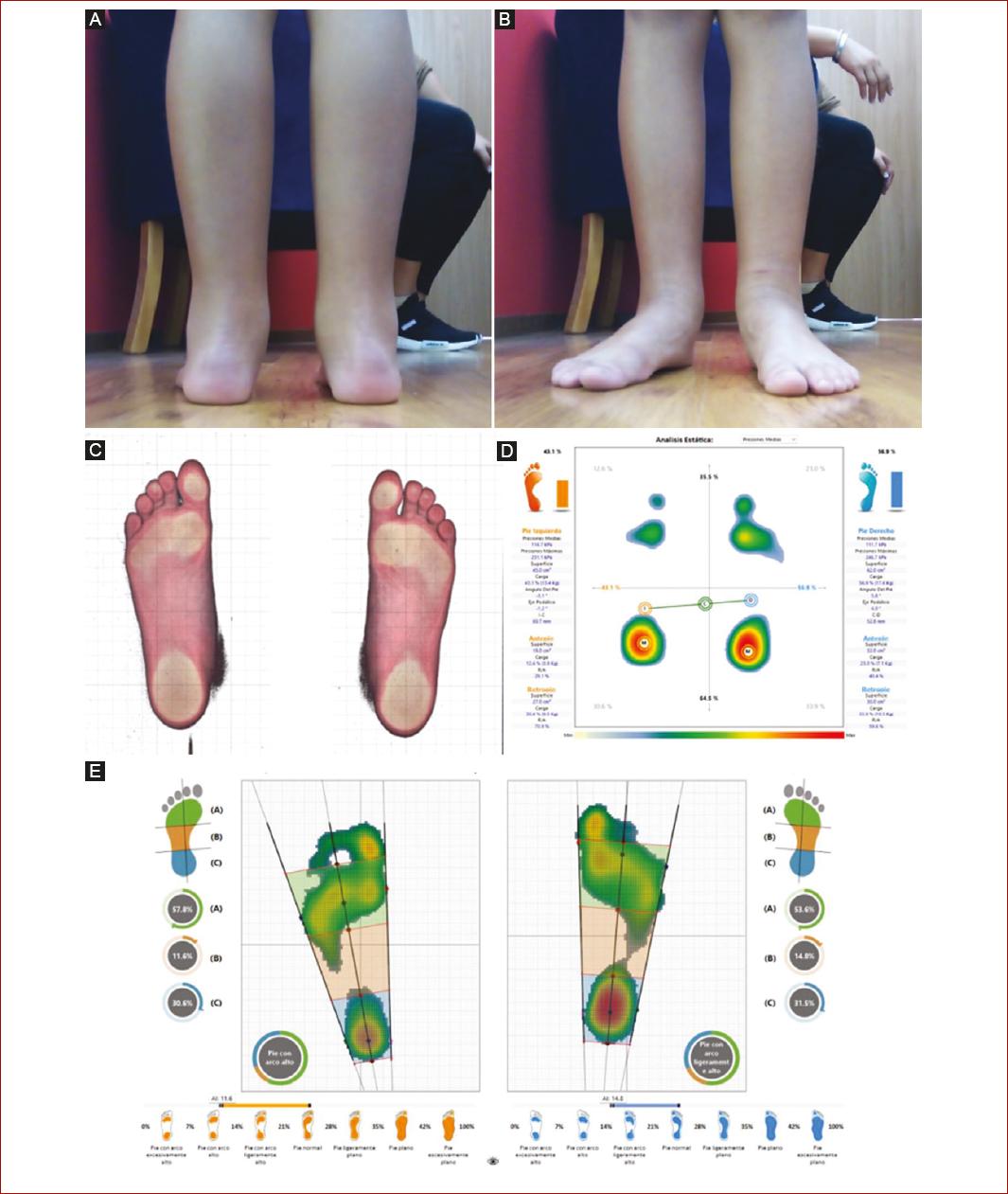

Lipedema is often associated with the presence of biomechanical alterations (Figs. 2 and 4), such as a shortened leg, metatarsals collapse, bunions (hallux valgus even quintus varus), genu valgum, and of course, a pronator footprint (feet going inward when impulsion), due to the pronation of the knee. Many patients with lipedema experience pain or discomfort on the medial aspect of the leg due to genu valgum, where the tissues are stretched, sometimes leading to the development of crows feet tendonitis. Pain or discomfort on the medial side of the ankle, usually below the medial malleolus, is common due to ankle pronation and tissue impingement in that area. Pain or discomfort on the lateral aspect of the lower leg, above or below the lateral malleolus, is due to tissue stretching secondary to the prone position of the ankle; among many other pains and discomforts in other regions, due to the tendency to damage almost every soft tissue, which is yet to be fully studied and understood.

Figure 4 Photo gallery, digital plantoscopy, static and dynamic baropodometry for biomechanical analysis of gait of a patient with lipedema, 9 years. A: posterior view of the legs with the same pronated position of the ankle, B: it can be seen the position in valgo of the knees, which obliges to compensate by forefoot abduction on both of the legs, same as the adult female, non-family-related, C: digital plantoscopy with a normal arc, it can be seen metatarsal collapse with clawed toes and hyperkeratosis on the metatarsals areas, quintus varo bilaterally, D: static baropodometry appears to have a high arch due to the pronation of the ankle, which relieves pressure from the external surface of the sole of the foot, E: dynamic baropodometry correlates better with plantoscopy although one must be careful to observe the arch and not confuse high arch with an ankle in pronation, as in this case. We can even predict the shorter leg in a patient with an ankle in pronation if we consider that the larger one will pronate more, and that the shorter usually abduces more the forefoot. In this case, the shorter leg by scanometry is the right one, and it coincides with the fact that the left ankle is the one with the greatest pronation (A), and the more abducted forefoot (B).

It is not unreasonable to think that these same biomechanical alterations tend to alter the posture of the patient, being responsible for most of the symptoms and complications these patients usually develop such as arthropathy, spondyloarthropathy, and therefore, mobility limitation, which, along with tissue weakness in part, could explain why venous disease or even lymphedema develops.

Lipedema is classified according to distribution into five degrees (Table 2) and according to severity into four stages (Table 3), although some authors only consider three stages1.

Table 2 Classification of lipedema. Current classification

| Type I | Abdomen, buttocks, and hips |

| Type II | Hips to knees |

| Type III | Hips to ankles |

| Type IV | Shoulders and arms |

| Type V | Isolated legs |

| Type VI | Generalized |

Table 3 Stages of lipedema. Current stages

| I | Normal skin, lumps can be felt under the skin, and there may be pain or burning |

| II | The skin is uneven, there may be depressions such as dimples that resemble quilted stitching or cottage cheese |

| III | Your legs may look like inflated rectangular balloons and have skin and fat folds. The folds can make walking difficult. |

| IV | Lipedema complicated with lymphedema |

Regarding these two classifications and stages, I think that it is too premature to try to use them extensively because they were created at a moment when we were unaware of the condition based on plastic surgery concepts, which are not important, given the complexity of the disease. We should not recommend that patients with lipedema understand it as an aesthetic problem; even less now that it is considered a connective tissue disease and, in my own experience, a dysautonomic condition, given the high prevalence of hypotension, orthostatic intolerance, alterations in thermoregulation, and other symptoms of dysautonomia that will not be addressed in this text, mainly because there is no more information on this topic than what Hines and Allen wrote in 1949: neurosis2.

Lipedema is a condition that is present from birth3 and develops during childhood; nonetheless, there is not much information regarding the condition in pediatric patients, but we can observe the same findings in this group (Fig. 4).

Lipedema is poorly understood, but I can conclude that it is a condition with many risk factors for the development of vascular diseases such as venous disease, lymphedema, venous thromboembolic disease, and perhaps even aneurysmal disease, as I have seen two patients with lipedema and facial hyperpulsatility. The important thing is that we as vascular surgeons and angiologists take the lead to understand and treat lipedema patients properly.

Treatments considered in lipedema

Lipedema treatment should primarily focus on patient awareness of their medical condition11, understanding why it is so difficult to control weight or gain muscle, and correcting all connective tissue alterations that accompany the disease, such as treatment targeting venous insufficiency and rehabilitation for those who require it, especially when accompanied by problems in the lumbar area and biomechanical gait alterations. Comprehensive treatment with other specialists as the case may require. It is important that patients with weight problems be treated by nutrition specialists in lipedema. Treatment options must always include backbone and joint hygiene. Therefore, treatment should focus on improving quality of life7,8,11, including psychosocial support, as it is often accompanied by insomnia, depression, anxiety, and eating disorders.

Vascular problems can be treated with the wide range of options we have, but I must insist on never forgetting compression therapy (Fig. 5) and biomechanical correction with insoles that can be indicated by a vascular specialist with the proper training. Insoles and rehabilitation are essential parts of the treatment to perpetuate improvements.

Figure 5 A patient with lipedema was detected because of the development of lymphedema, a 37-year-old female patient. Compression therapy is an extraordinary option to treat these patients and should always be considered the base of the treatment for venous and lymphatic diseases, with bandages or compression stockings, V technique was used for bandages and reversion technique in stockings.

Many patients with lipedema have hypothyroidism and sleeping conditions that may perpetuate the weight problem7 that must be addressed too. In my experience, dermatologic conditions such as eczema, eczema-like (psoriasis and atopic skin), and rosacea can be seen too, along with the frequent presence of livedo reticularis and bruises. Surgical esthetic procedures should be discouraged in these groups of patients.

Patients with lipedema should be scrutinized for symptoms of arterial disease1 and dysautonomia such as bradycardia, hypotension, orthostatic hypotension, thermoregulatory alterations, and even gastrointestinal dysautonomic symptoms. It is recommendable to guide patients in autonomic hygiene.

Metabolic disease is as frequent as in the general population among these patients, but metabolic studies must be performed too.

I find many weaknesses in the present article, starting with the shortage of scientific articles on the topic and the strong dominance of an esthetic perspective. Another is that we are not trained as angiologists and vascular surgeons in Mexico to recognize and treat lipedema, and lipedema is not even considered a vascular condition. The topic is absent in the main consultation books for vascular pathology; ergo, I had been working on understanding lipedema on my own. Another weakness is that I initially considered lipedema as a very recently recognized condition and limited the search process to 2018. Clinical criteria suggested in this article cannot be applied until the correct methodological process is performed to establish prevalences and frequencies, but this criterion is just the beginning and fulfills the purpose of the article: draw attention to the condition in our vascular community.

Conclusion

Lipedema is a frequent condition underrecognized and confused with traditional obesity and other traditional vascular diseases. The condition can develop even in childhood as the case presented and can be present comorbidity with any other condition; therefore, all the medical communities should be familiar with the disease, even if it only develops mild signs or symptoms. Vascular physicians should be the ones with the more experience in these groups of patients, because there is a high prevalence of vascular diseases. The first criteria for the condition were described by Hines and Allen, not Wold (the first author in the article) as some authors suggested2,5; nonetheless, the symptoms described are scarce and poorly specific.

I encourage the medical community participating in the treatment of lipedema to establish common clinical criteria and treatment options through the best methodological processes. There are numerous lines of research on this topic, such as prospective studies to determine the exact prevalence of the disease, the diagnostic criteria presented in the literature and in this article, the validation of baropodometry in treatment, the effectiveness of biomechanical correction in the improvement of this vascular disease, the effect of biomechanical correction with insoles on ambulatory venous pressure in patients with or without venous disease, among many others.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)