Introduction

Chronic venous disease (CVD) is a prevalent condition in Mexico, affecting 71.3% of the population1, and imposes a major burden on the healthcare system. The pathophysiology of CVD is complex, involving genetic and environmental factors, venous hypertension, inflammation, and valvular incompetence2. This creates a vicious cycle of disease progression with a 4% annual progression rate of 4% and a 50% recurrence within 5 years post-treatment. CVD tends to worsen in older populations and those with obesity3,4. Although non-lethal, CVD significantly impacts the quality of life (QoL), affecting patients physically and psychologically at all stages of the condition, often without a direct correlation to the severity of clinical signs5,6.

The main goals of CVD treatment are to improve venous function and alleviate clinical symptoms. However, evidence suggests that CVD is underdiagnosed and undertreated, particularly in its early stages7, with the specific role of venoactive drugs (VADs) remaining controversial. Gathering treatment data from individual countries to understand the disease better and improve planning for proper prevention and treatment programs at the national level is important.

We analyzed data from a population in Mexico recruited for the VEIN STEP study8 to evaluate the effectiveness of conservative treatments on CVD manifestations and QoL and to generate nationally representative data to improve our understanding of the diseases different settings.

Methods

In this prospective, multicenter, cohort study, general practitioners (GPs) and vascular surgeons from 41 centers across Mexico recruited consecutive adult patients with symptomatic CVD. Patients were excluded if they were already receiving treatment with VADs or compression hosiery, had lower limb arterial disease, possessed any concomitant condition affecting lower limb pain or edema, were planning any CVD-related procedures or surgeries, or were pregnant or breastfeeding. Ethical approval was obtained, and the study complies with European Regulation EU 536/2014. Data was collected anonymously, and the study is registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04574375). We adhered to the strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology guidelines when preparing this paper.

The study's primary objective was to evaluate the effectiveness of conservative treatments for CVD symptoms. Secondary objectives assessed the impact on QoL, patient and physician satisfaction, and general disease management.

Detailed demographic and medical data were recorded at the initial visit (V0). Patients were classified according to the clinical, etiological, anatomical, and pathophysiological (CEAP) classification9. Using a 10-cm visual analog scale (VAS)10, patients were asked to indicate the global intensity of their symptoms and the intensity of each symptom (pain, heaviness, cramps, and sensation of swelling). The intensity of paresthesia, itching, and burning sensation symptoms were assessed with a four-point scale (none, mild, moderate, or severe). The patients QoL was assessed using the 14-item chronic venous insufficiency QoL questionnaire (CIVIQ-14)11 covering pain, physical, and psychological domains and reported as a global index score (GIS) to be standardized from 0 to 100. The questionnaire has been validated and is a reliable and sensitive instrument12,13. In addition, the venous clinical severity score (VCSS)14 was used to gauge the severity of venous symptoms based on ten clinical descriptors, with a maximum score of 30.

Following V0, patients received conservative treatments as per physicians' usual practices, which included pharmacological (oral VADs, painkillers, topical treatment, etc.,) and non-pharmacological (compression therapy, lifestyle advice, etc.,) options. Symptom improvement was first assessed at a week-2 telephone follow-up (V1) using the seven-point patient global impression of change (PGIC) questionnaire, where patients also reported symptom-specific improvements and time to improvement. At the week-4 follow-up (V2), physicians reassessed patients using the VAS, PGIC, CIVIQ-14, and VCSS and evaluated treatment satisfaction on a five-item scale. An optional week-8 follow-up (V3) through telephone further assessed PGIC and collected data on treatment adherence, lifestyle recommendations, and adverse events.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are described by mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range); 95% two-sided confidence intervals (CI) were calculated when appropriate. Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages. Missing data were not replaced. Within-group differences were evaluated by a paired t-test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test for continuous variables with a normal or skewed distribution, respectively. Statistical significance was assumed when p < 0.05 (two-sided). All statistical analyses were performed with the Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) version 9.4 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Baseline demographic and patient characteristics

Between July 2021 and February 2022, 42 physicians in Mexico screened 807 patients, with 794 meeting the analysis criteria. Of these, 749 completed all required visits, and 589 attended an optional follow-up. Among the analyzed patients, 75.9% were female with a mean age of 52 years, 95.3% identified as Latino/Hispanic, and the mean body mass index (BMI) was 28.4 kg/m2. Lifestyle data showed that 48.7% were sedentary, and 34.5% had jobs requiring standing for over 5 h daily. A family history of CVD was reported by 58.9%, with hypertension (22.4%) and diabetes (17.1%) being the most common comorbidities. In addition, 16.2% of participants had other venous disorders, primarily hemorrhoidal disease. Demographic and clinical data are summarized in table 1.

Table 1 Baseline demographic data of recruited patients

| Characteristics | C0s-C1 (n = 240) | C2 (n = 244) | C3 (n = 154) | C4a (n = 78) | C4b (n = 43) | C5 (n = 9) | C6 (n = 26) | Overall (n = 794) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||||

| Male | 49 (20.4) | 43 (17.6) | 46 (29.9) | 22 (28.2) | 14 (32.6) | 2 (22.2) | 14 (53.8) | 191 (24.1) |

| Female | 189 (79.1) | 201 (82.4) | 108 (70.1) | 56 (71.8) | 29 (67.4) | 7 (77.8) | 12 (46.2) | 603 (75.9) |

| Age (y), mean (SD) | 46.1 (13.5) | 52.1 (13.2) | 53.3 (14.9) | 58.2 (11.7) | 59.4 (11.9) | 58.8 (10.0) | 64.9 (13.1) | 52.0 (14.2) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Latino/hispanic | 222 (93.3) | 233 (95.5) | 149 (96.8) | 75 (96.2) | 41 (95.3 | 9 (100) | 26 (100) | 757 (95.3) |

| Caucasian/white | 14 (5.9) | 7 (2.9) | 4 (2.6) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (4.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 28 (3.5) |

| Asian | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.6) |

| BMI (kg/m2) mean (SD) | 27.3 (4.8) | 28.0 (4.5) | 28.8 (4.7) | 30.6 (4.8) | 29.5 (4.6) | 29.8 (5.3) | 29.8 (5.4) | 28.4 (4.8) |

| BMI range, n (%) | ||||||||

| < 18.5 | 3 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.6) |

| 18.5-24.9 | 77 (32.5) | 64 (26.2) | 33 (21.4) | 11 (14.1) | 7 (16.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (15.4) | 197 (24.8) |

| 25.0-30.0 | 94 (39.5) | 110 (45.1) | 61 (39.6) | 23 (29.5) | 18 (41.9) | 2 (22.2) | 12 (46.2) | 320 (40.3) |

| ≥ 30.0 | 65 (27.0) | 70 (28.7) | 59 (38.3) | 44 (56.4) | 18 (41.9) | 6 (66.7) | 10 (38.5) | 272 (34.3) |

| Lifestyle, n (%) | ||||||||

| Sedentary | 95 (39.5) | 119 (48.8) | 87 (56.5) | 36 (46.2) | 22 (51.2) | 7 (77.8) | 21 (80.8) | 387 (48.7) |

| Active occupation | ||||||||

| No | 13 (5.5) | 20 (8.2) | 15 (9.7) | 4 (5.1) | 4 (9.3) | 3 (33.3) | 5 (19.2) | 64 (8.1) |

| Normal task | 84 (35.0) | 91 (37.3) | 50 (32.5) | 26 (33.3) | 17 (39.5) | 1 (11.1) | 8 (30.8) | 277 (34.9) |

| Prolonged | 77 (32.0) | 82 (33.6) | 60 (39.0) | 33 (42.3) | 13 (30.2) | 2 (22.2) | 7 (26.9) | 274 (34.5) |

| standing | 65 (27.3) | 47 (19.3) | 29 (18.8) | 11 (14.1) | 9 (20.9) | 1 (11.1) | 6 (23.1) | 168 (21.2) |

| Prolonged sitting | 1 (0.4) | 4 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (5.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (1.4) |

| Heavy lifting | 146 (60.8) | 140 (57.4) | 93 (60.4) | 46 (59.0) | 24 (55.8) | 4 (44.4) | 15 (57.7) | 468 (58.9) |

| Family history of CVD | 19 (7.9) | 66 (27.0) | 47 (30.5) | 27 (34.6) | 20 (46.5) | 7 (77.8) | 15 (57.7) | 201 (25.3) |

| History of CVD treatment | 16 (6.6) | 55 (22.9) | 39 (25.3) | 23 (29.4) | 16 (37.2) | 6 (66.6) | 12 (46.1) | 167 (90.3) |

| VADs | 5 (2.0) | 20 (20.5) | 21 (13.6) | 11 (14.8) | 7 (16.2) | 5 (55.6) | 9 (34.6) | 78 (38.8) |

| Compression therapy | 3 (1.2) | 12 (4.9) | 4 (2.6) | 4 (5.1) | 2 (4.6) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (11.5) | 28 (3.5) |

| Interventions | 28 (11.6) | 33 (13.5) | 32 (20.8) | 15 (19.2) | 8 (18.6) | 5 (55.6) | 8 (30.8) | 129 (16.2) |

| Other vein disorders | 27 (11.2) | 29 (11.9) | 28 (18.2) | 13 (16.6) | 8 (18.6) | 1 (11.1) | 5 (19.2) | 111 (13.9) |

| Hemorrhoidal disease | 1 (0.4) | 4 (1.6) | 4 (2.6) | 2 (2.5) | 1 (2.3) | 2 (22.2) | 2 (7.7) | 16 (2.0) |

| DVT | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) |

| PTS | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 3 (0.3) |

| PCS | ||||||||

| Other comorbidities | ||||||||

| No | 186 (77.5) | 177 (72.5) | 89 (57.8) | 29 (37.2) | 14 (32.6) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (46.2) | 507 (63.9) |

| Hypertension | 32 (13.4) | 38 (15.6) | 40 (26.0) | 32 (41.0) | 20 (46.5) | 6 (66.7) | 10 (38.5) | 178 (22.4) |

| DM | 22 (9.5) | 28 (11.5) | 30 (19.5) | 22 (28.2) | 18 (41.9) | 6 (66.7) | 9 (34.6) | 136 (17.1) |

| Thyroid disease | 12 (5.0) | 13 (5.3) | 4 (2.6) | 4 (5.1) | 2 (4.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 35 (4.4) |

CVD: chronic venous disease; SD: standard deviation; n: number of patients; BMI: body mass index; Sx: syndrome; y: years; Sx: syndrome; DVT: deep vein thrombosis; PTS: post-thrombotic syndrome; DM: diabetes mellitus; PCS: pelvic congestive syndrome. Some patients reported more than one chronic comorbidity.

Baseline clinical characteristics

A greater proportion of women were classified as C1-C3, whereas more men were classed as C4-C6. CVD symptoms were prevalent across all CEAP classifications. Leg pain and heaviness were the most frequent symptoms (90.4 and 94.6%, respectively). Symptoms were present daily in 51.8% of patients and were more likely to be experienced after prolonged standing or at the end of the day. The mean global symptom VAS score across the CEAP classes was 5.8 ± 2.6, with a gradual increase in each successive CEAP class. Leg telangiectasis, varicose veins, and edema were the most frequent CVD signs reported (30, 30.7, and 19.4%, respectively).

The CIVIQ-14 means GIS at baseline was 34 ± 21.4. The QoL score varied across CEAP classes, with a moderate impact in patients with a classification of C0-C3 (mean GIS: 7.2-36.7) and a high impact in those with a CEAP classification of C4b-C6 (mean GIS: 49-58.9).

Treatments prescribed at baseline

At V0, Oral VADs were prescribed to 95.8% of patients, either as monotherapy (18.9%) or in combination with other treatments. The most prescribed VAD was micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF), given to 80.2% of VAD recipients, followed by diosmin (12.6%). Compression therapy, either elastic or inelastic, was recommended for 70.9% of patients. Combination therapy was more frequently prescribed for patients at higher CEAP stages. In addition, nearly all patients (99.5%) received lifestyle advice, which included regular exercise, weight management, and avoiding long periods of standing or sitting, among others (Table 2).

Table 2 Treatment recommendations at V0 according to the CEAP category and overall

| Characteristic, n (%) | C0s-C1 (n = 240) | C2 (n = 244) | C3 (n = 154) | C4a (n = 78) | C4b (n = 43) | C5 (n = 9) | C6 (n = 26) | Overall (n = 794) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advice regarding lifestyle | ||||||||

| Yes | 237 (98.7) | 244 (100) | 154 (100) | 78 (100) | 42 (97.7) | 9 (100) | 26 (100) | 790 (99.5) |

| No | 3 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.5) |

| Compression therapy | ||||||||

| No | 108 (45.0) | 60 (24.6) | 34 (22.1) | 17 (21.8) | 9 (20.9) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (7.7) | 231 (29.1) |

| Yes | 132 (55.0) | 184 (75.4) | 120 (77.9) | 61 (78.2) | 34 (79.1) | 8 (88.8) | 24 (92.3) | 563 (70.9) |

| Bandages | 7 (2.9) | 15 (8.2) | 19 (15.8) | 12 (19.7) | 8 (18.6) | 1 (11.1) | 17 (66.1) | 79 (9.9) |

| Elastic | 6 (2.5) | 11 (73.3) | 14 (73.7) | 9 (75.0) | 4 (9.3) | 1 (11.1) | 14 (53.8) | 60 (7.5) |

| Non-elastic | 0 (0.0) | 4 (26.7) | 5 (26.3) | 3 (25.0) | 4 (9.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (15.3) | 20 (2.5) |

| Stockings, | 126 (96.2) | 171 (92.9) | 106 (88.3) | 50 (82.0) | 26 (60.4) | 7 (77.7) | 8 (30.7) | 494 (62.2) |

| Mild (8-15 mmHg) | 12 (9.5) | 9 (5.3) | 3 (2.8) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 26 (3.2) |

| Moderate (15-20 mmHg) | 39 (31.0) | 30 (17.5) | 32 (30.2) | 9 (18.0) | 4 (9.3) | 1 (11.1) | 3 (11.5) | 118 (14.8) |

| Firm (20-30 mmHg) | 75 (59.5) | 130 (76.0) | 68 (64.2) | 40 (80.0) | 21 (48.8) | 1 (11.1) | 5 (19.2) | 340 (42.8) |

| Extra firm (30-40 mmHg) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) | 3 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (0.8) |

| Very firm (> 40 mmHg) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Not defined | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) |

| Below-knee | 88 (69.8) | 86 (50.3) | 69 (65.1) | 23 (46.0) | 12 (27.9) | 2 (22.2) | 5 (19.2) | 285 (35.8) |

| Compression compliance | ||||||||

| Occasionally | 5 (4.0) | 5 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (1.3) |

| Regularly | 98 (77.8) | 120 (70.2) | 67 (63.2) | 31 (62.0) | 13 (30.2) | 2 (22.2) | 3 (11.5) | 334 (42.0) |

| Year-round | 23 (18.3) | 46 (26.9) | 39 (36.8) | 19 (38.0) | 13 (30.2) | 4 (44.4) | 5 (19.2) | 149 (18.7) |

| Oral VAD | ||||||||

| Calcium dobesilate | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.2) | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 6 (0.8) |

| Diosmin | 22 (9.9) | 47 (19.2) | 13 (8.4) | 9 (11.5) | 2 (4.6) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (11.5) | 96 (12.0) |

| MPFF | 197 (82.0) | 168 (68.8) | 118 (76.6) | 66 (84.6) | 31 (72.0) | 9 (100) | 21 (80.7) | 610 (76.8) |

| Oxerutin/Troxerutin | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 4 (0.5) |

| Ruscus extract | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.8) | 4 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (6.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (1.3) |

| Sulodexide | 1 (0.4) | 4 (1.6) | 4 (2.6) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (4.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 13 (1.6) |

| VAD combination | 3 (1.3) | 10 (4.0) | 5 (3.2) | 1 (1.3) | 4 (9.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 22 (2.8) |

| Painkillers | ||||||||

| Paracetamol | 8 (18.6) | 22 (20.0) | 19 (12.3) | 5 (6.4) | 3 (6.9) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (23.0) | 63 (7.9) |

| Other NSAIDs | 32 (74.4) | 84 (76.4) | 33 (21.4) | 16 (20.5) | 9 (20.9) | 5 (55.5) | 11 (50.6) | 194 (24.4) |

| Aspirin | 3 (7.0) | 3 (2.7) | 2 (1.3) | 5 (6.4) | 1 (2.3) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (1.8) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 4 (19.0) | 8 (1.0) |

| Topical treatment | ||||||||

| No | 224 (97.5) | 230 (94.3) | 123 (79.9) | 65 (83.3) | 40 (9.3) | 5 (55.5) | 14 (53.8) | 701 (88.2) |

| Yes | 16 (6.6) | 14 (5.7) | 31 (20.1) | 13 (16.7) | 3 (6.9) | 4 (44.4) | 12 (46.2) | 93 (11.7) |

| Corticosteroids | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (16.7) | 2 (0.2) |

| Local anesthetics | 4 (26.7) | 2 (14.3) | 7 (4.5) | 5 (6.4) | 1 (2.3) | 2 (22.2) | 2 (16.7) | 23 (2.8) |

| Venoactive drugs | 7 (2.9) | 10 (71.4) | 16 (10.3) | 7 (8.9) | 1 (2.3) | 3 (33.3) | 1 (8.3) | 45 (5.6) |

| Other | 5 (33.3) | 2 (14.3) | 8 (5.1) | 3 (3.84) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (83.3) | 29 (3.6) |

Patients usually receive a combination of treatments, especially in higher C-stages. CEAP: clinical-etiology-anatomy-pathophysiology; C: clinical parameter from CEAP; V0: baseline visit; SD: standard deviation; n: number of patients; NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; VAD: venoactive drug; HCSE: horse chestnut seed extract; MPFF: micronized purified flavonoid fraction.

Treatment effectiveness

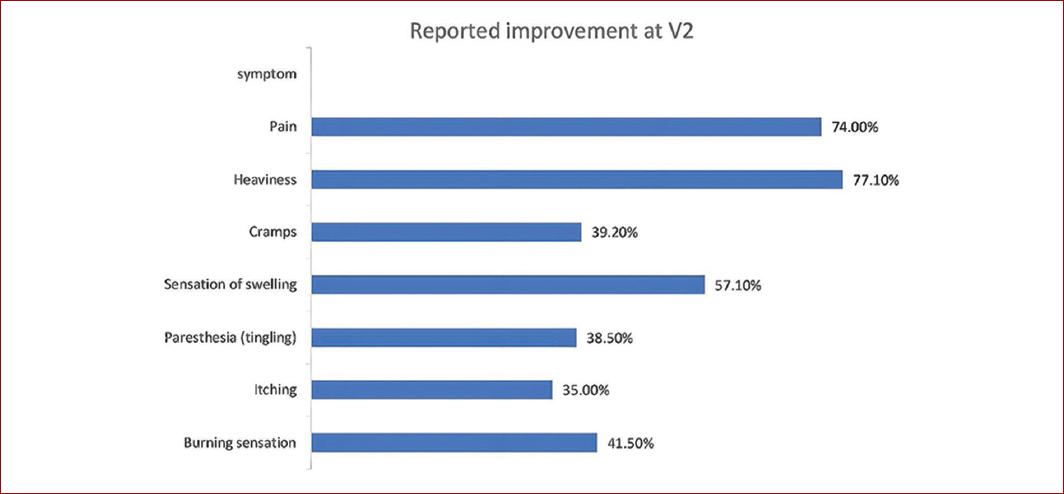

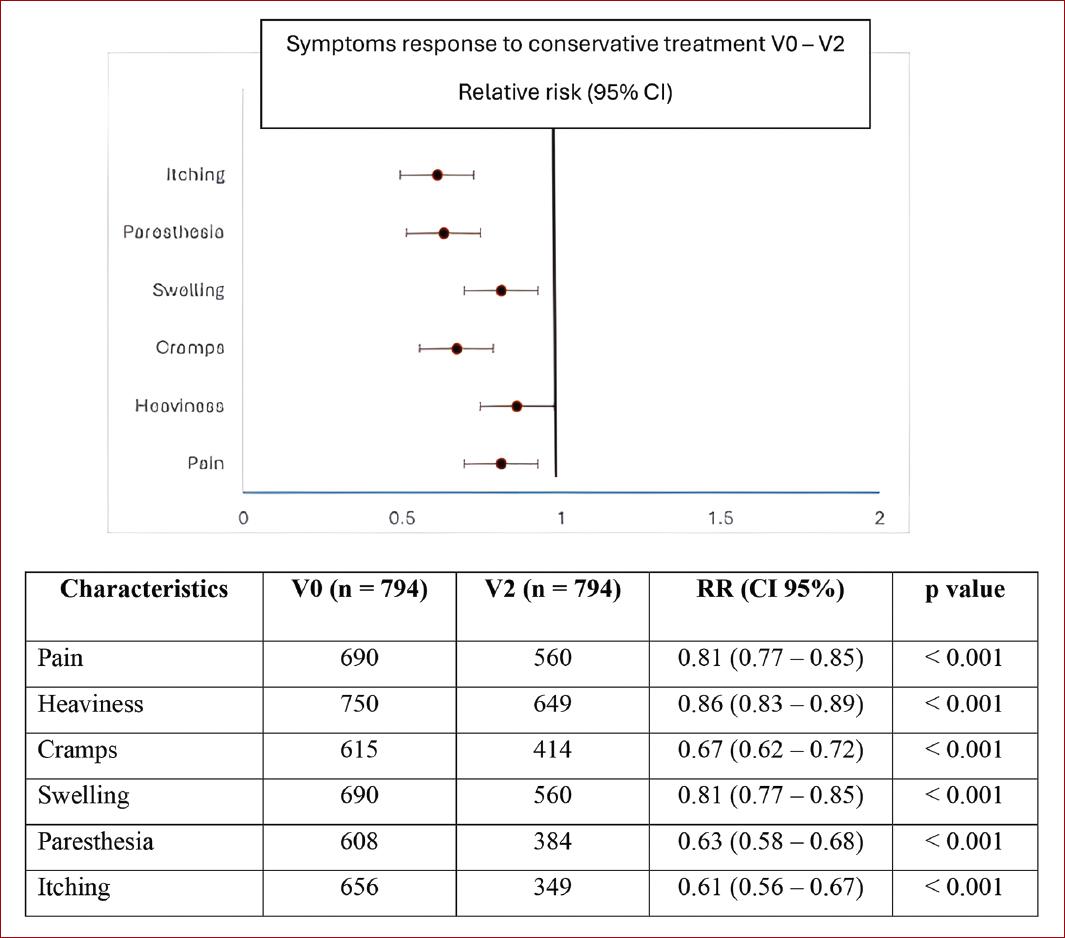

According to the PGIC, overall symptom improvements were noted in 93.6% of patients at V1 and in 94.6% at V2. At the optional V3, of 588 patients evaluated, 99.4% reported improvements in symptoms. Benefits were observed across all CEAP stages as displayed in table 3. The individual symptoms that improved the most according to the PGIC were heaviness and pain, (77.1 and 74%, respectively) (Fig. 1). However, the relative risk at V2 was lower for itching at 0.61 (95% CI 0.56-0.67) and paresthesia at 0.63 (95% CI 0.58-0.68) (Fig. 2).

Table 3 CVD conservative treatment outcomes results. Patient description of change from baseline to evaluation visits according to CEAP stages for Global and individual symptom severity assessed with VAS, PGI-C, VCSS, and CIVIQ-14 global index score

| Outcome evaluation | C0s-C1 (n = 240) | C2 (n = 244) | C3 (n = 154) | C4a (n = 78) | C4b (n = 43) | C5 (n = 9) | C6 (n = 26) | Overall (n = 794) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global symptom VAS | ||||||||

| VAS V0 | 5.0 (2.4) | 6.0 (2.5) | 5.4 (2.5) | 6.4 (2.9) | 7.3 (2.3) | 7.8 (1.5) | 6.8 (2.4) | 5.8 (2.6) |

| VAS V2 | 2.6 (1.7) | 3.4 (2.2) | 2.6 (1.7) | 4.0 (2.5) | 4.5 (1.7) | 4.2 (1.4) | 3.8 (1.6) | 3.2 (2.1) |

| Change from V0 to V2 | 2.4 (2.0) | 2.6 (1.7) | 2.8 (2.0) | 2.4 (2.0) | 2.8 (1.8) | 3.6 (1.7) | 3.0 (2.5) | 2.6 (1.9) |

| Days to symptoms improvement, mean (SD) | 7.1 (2.9) | 7.0 (3.1) | 6.2 (3.0) | 6.4 (3.5) | 5.2 (2.6) | 6.2 (3.2) | 6.9 (4.3) | 6.7 (3.2) |

| PGI-C from V0 to V1, n (%) | ||||||||

| Improvement | 227 (94.5) | 225 (92.2) | 146 (94.8) | 74 (94.9) | 38 (88.3) | 9 (100) | 24 (92.3) | 743 (93.6) |

| No change | 4 (1.6) | 3 (1.2) | 4 (2.6) | 3 (3.8) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.7) | 17 (2.1) |

| Worsening | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (1.3) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.6) |

| PGI-C from V0 to V2, n (%) | ||||||||

| Improvement, n (%) | 225 (93.7) | 233 (95.4) | 144 (93.5) | 73 (93.5) | 42 (97.7) | 9 (100) | 25 (96.1) | 751 (94.6) |

| No change, n (%) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.3%) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (0.8) |

| Worsening, n (%) | 3 (1.2) | 3 (1.2) | 5 (3.2) | 2 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (1.6) |

| VCSS, mean (SD) | ||||||||

| V0 | 4.2 (2.8) | 6.2 (3.4) | 6.2 (3.2) | 9.2 (4.3) | 8.8 (2.8) | 14.9 (4.1) | 16.5 (3.5) | 6.3 (4.1) |

| V2 | 3.0 (2.0) | 4.5 (2.2) | 4.7 (2.8) | 6.3 (3.4) | 6.4 (2.5) | 9.2 (3.1) | 11.0 (4.4) | 4.4 (2.9) |

| V0-V2 score change | 1.2 (2.4) | 1.7 (2.5) | 1.5 (2.4) | 2.9 (3.5) | 2.4 (2.4) | 5.7 (3.1) | 5.5 (4.7) | 1.9 (2.8) |

| CIVIQ-14, mean (SD) | ||||||||

| GIS-V0 | 23.6 (14.9) | 33.9 (20.9) | 36.7 (22.6) | 45.6 (21.4) | 49.0 (20.9) | 58.9 (24.4) | 52.8 (18.0) | 34.0 (21.4) |

| GIS-V2 | 11.7 (10.6) | 19.6 (15.9) | 19.6 (16.1) | 27.1 (17.6) | 30.3 (17.3) | 31.9 (13.9) | 25.5 (17.9) | 18.8 (15.9) |

| GIS from V0 to V2 | 11.9 (9.9) | 14.3 (12.0) | 17.1 (13.5) | 18.5 (14.3) | 18.7 (11.5) | 27.0 (17.6) | 27.3 (20.0) | 15.2 (12.6) |

CEAP: clinical-etiology-anatomy-pathophysiology; C: Clinical parameter from CEAP; VAS: visual analog scale; PGI-C: patient global impression of change; n: number of patients; V0: baseline visit; V1: week-2 visit; V2: week-4 visit; SD: standard deviation; CIVIQ-14: 14-item chronic venous insufficiency quality of life questionnaire; GIS: global index score. *p < 0.001 along all (C) stages (Inferential analysis of change from V0 to V2 calculated with Wilcoxon signed rank test p value).

Figure 1 CVD conservative treatment individual symptoms outcomes results. The graphic represents the percentage of patients, according to the PGIC, who reported an improvement in each evaluated CVD symptom at V2 (although symptoms may persist). PGIC: patient global impression of change; V2: week-4 visit.

Figure 2 CVD conservative treatment individual symptoms outcomes results. The graphic represents individual CVD symptoms reported by patients at V0 that persisted at V2. CVD: chronic venous disease, V0: baseline visit; V2: week-4 visit; RR: relative risk; CI: confidence interval.

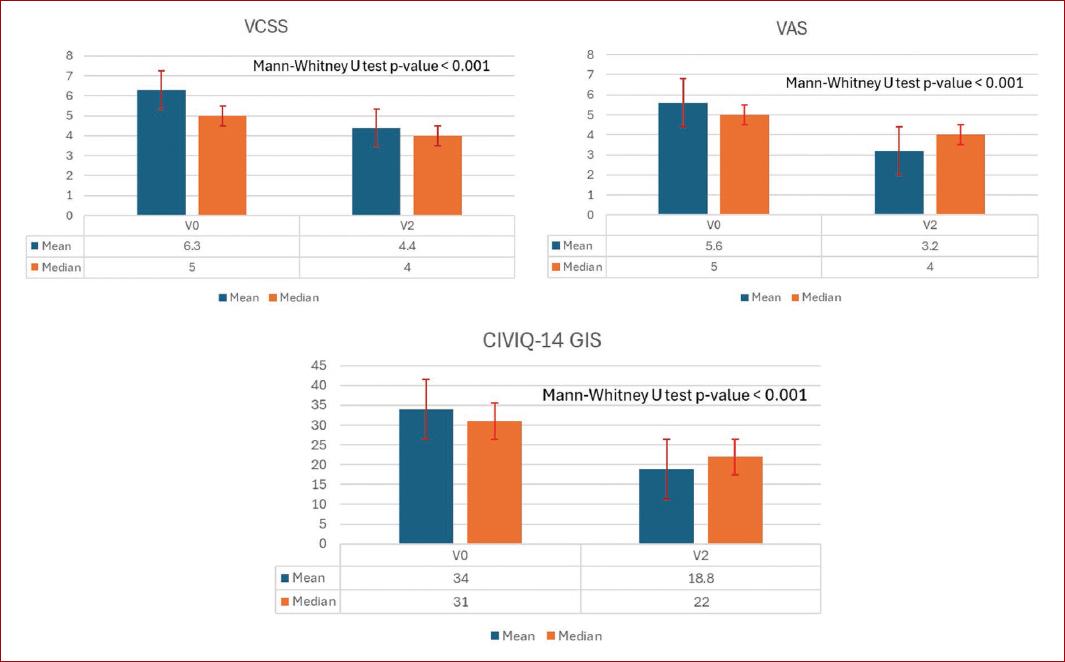

According to the VAS, global symptom intensity improved from a mean of 5.8 ± 2.6 at V0 to 3.2 ± 2.1 at V2 (p < 0.001). Improvement was achieved within a mean time of 6.7 ± 3.2 days and was observed regardless of whether VADs were prescribed as monotherapy or in combination with other treatments. Improvements were greatest in CEAP classes C4b and above, which also had the highest VAS scores at baseline. The population exhibited an overall decrease in the VCSS at V2, from a mean of 6.3 ± 4.1 to 4.4 ± 2.9 (p < 0.001) and this was more evident in patients with higher CEAP classes. The CIVIQ-14 GIS improved from V0 to V2 by a mean of 15.2 ± 12.6 points (p < 0.001). This was observed across all three CIVIQ-14 dimensions. The VAS, VCSS, and CIVIQ-14 GIS overall mean differences from V0 to V2 are summarized in figure 3.

Figure 3 Chronic venous disease conservative treatment outcomes. Overall mean and median VCSS, VAS, and CIVIQ-14 GIS calculated values at V0 and V2. VAS: visual analog scale; CIVIQ-14 GIS: 14-item chronic venous insufficiency quality of life questionnaire global index score; VCSS: venous clinical severity score; V0: baseline visit; V2: week-4 visit. Median values were used to calculate the Mann-Whitney U test value of p.

89.3% of the patients and 88.7% of physicians were satisfied with the prescribed treatment.

Adherence to conservative treatment and adverse events

At V2, adherence to lifestyle advice was 96.6%. Adherence to VADs was 98.5%, and adherence to compression was 88%, although 13.1% of participants who used compression did not wear it as prescribed. The main reasons for non-adherence to compression were difficulty putting it on (36.1%), discomfort of the hosiery (16.4%), sweating (11.5%), and skin irritation (8.2%). No serious adverse events requiring the suspension of medication were reported with VAD.

Discussion

This study provides insight into the management of CVD in daily clinical practice in a population in which 95.3% of patients were of Latino/Hispanic origin. This is particularly important since CVD data from Mexican populations are scarce, especially from multicenter studies.

Compared to the VEIN STEP-Global study, Mexican data revealed higher rates of a BMI > 30 (34.3 vs. 30.4%), sedentary lifestyle (48.7 vs. 40%), and diabetes mellitus (17.1 vs. 13.3%). In addition, Mexican patients had a higher incidence of advanced CVD (C4-C6 classification) at 19.5 versus 12.8% in the global cohort. These differences highlight the importance of collecting region-specific data, as CVD characteristics and risk factors may vary by geographic location15.

In this study, the reported symptoms are in line with previous epidemiological data on CVD in Mexico1 where symptoms affected QoL even at early stages of the disease. Despite this, only 25.3% of our patients had received previous treatment for venous leg disorders.

Clinical guidelines recommend conservative therapy as the initial treatment to improve symptoms and QoL in patients with CVD as an adjunct or alternative to interventional treatment16, with lifestyle advice, compression stockings, and VADs forming the mainstay of management2. CVD patients are generally less physically active than those without CVD, potentially leading to weight gain and disease progression17. Caggiati et al.18 concluded that lifestyle protocols should be tailored to the specific needs of each patient and should depend not only on the severity of CVD but also on age, motor deficits, comorbidities, and psychosocial conditions. Although physicians recommended lifestyle changes to most patients at V0, these recommendations varied, and their impact was difficult to assess, as outcomes from lifestyle changes, such as weight loss, diet, and exercise typically require extended periods to manifest.

Graduated compression therapy, which alleviates CVD symptoms and controls edema19,20, was prescribed to 70.9% of patients in this study, achieving an 88% compliance rate. However, adherence remains a significant challenge, particularly over time21,22. This issue is exacerbated among older adults with limited mobility, individuals with morbid obesity, and those residing in hot, tropical climates2,19.

In Mexico, VADs are often prescribed alongside lifestyle advice and elastic compression for symptom relief in CVD1. However, the effectiveness of VADs in CVD management remains debated. A Cochrane review of 56 randomized trials with 7,690 participants indicated that VADs might reduce leg edema and some CVD symptoms but showed moderate-certainty evidence of higher adverse event risks and no significant impact on QoL23. In contrast, a meta-analysis by Kakkos et al.24,25 specifically on MPFF found improvements in CVD symptoms, edema, and QoL. In this study, physicians prescribed oral VADs to 95.8% of patients, either as monotherapy for early-stage CVD (C0s-C3) or in combination for advanced stages (C4-C6), with MPFF prescribed to 76.8% of patients and diosmin to 12%. Adherence to VAD treatment was high. Supporting this, Kim et al. found that while VADs may have more adverse events, these events were generally mild, with patients prioritizing symptom improvement over potential risks. European guidelines recommend VADs due to their benefits in alleviating clinical CVD manifestations, and adverse events are typically mild and non-disruptive to adherence2,24.

Consistent with VEIN STEP- Global results, in Mexico, overall symptom intensity was reduced from a mean of 5.8 ± 2.6 at baseline to 3.2 ± 2.1 at V2, with significant improvements for all CEAP classes. VCSS scores were also improved at 4 weeks. These results complement other large international observational studies on CVD, such as VEIN CONSULT25,26 and VEIN ACT27, by focusing on the effectiveness of current CVD management from the perspectives of the patient and the physician.

Reductions in symptom severity also improved QoL overall and across the three CIVIQ-14 dimensions. Bogachev et al. reported similar findings in a smaller-scale real-world study, in which MPFF was added to conservative therapy for 6 months28. In the present study, CIVIQ-14 scores showed progressive deterioration in QoL from CEAP C0s to C6, which is similar to the observation made by Radak et al.29 on the relationship between CIVIQ-14 and CEAP that primarily involved pain and physical limitations in older patients and women. The RELIEF trial also demonstrated that age had a highly significant effect on global scores but not on psychological scores30. The results of this study are in line with previous data showing that QoL can be affected by even mild or moderate CVD symptoms31. This highlights the importance of an early CVD diagnosis and treatment initiation to reduce symptoms and prevent progression to more severe forms of the disease.

This studys strengths include its observational design, providing real-world data, a large, multi-region and consecutive patient recruitment for better representativeness, and a high completion rate for V2 evaluations. However, limitations include potential selection bias due to physician choice, variability in patient management, and non-randomized treatment allocation. The study only included patients with CVD-related complaints and did not assess the reliability or responsiveness of the CIVIQ-14 QoL questionnaire. Diagnoses were mainly made by GPs without specialist confirmation, and the CEAP classification used was limited to its clinical component.

Conclusion

The VEIN STEP study in Mexico provides valuable data on the management of patients with CVD. We observed that patients with CVD present with a broad range of symptoms and clinical stages, and the impact on QoL is usually greater in patients with more severe CVD. This study supports the effectiveness of conservative therapies, including VADs, as monotherapy or in combination with other treatments, in managing CVD symptoms and improving QoL. These results from a Mexican population could serve as a basis for future research and help inform potential future updates to CVD prevention and treatment programs in Mexico.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)