Abstract

Hypoxic-ischemic brain injury refers to the pathophysiological consequence of deprivation of adequate cerebral perfusion that occurs transiently. This medical complication is commonly related to an event of cardiac arrest (CA), respiratory failure, incidents of near drowning, and different states of shock that could trigger severe hypoperfusion and its pathological sequelae. The consequences of this clinical entity can vary from almost complete recovery to brain death. Treatment is based on correcting the cause of hypoperfusion, adequate neurocritical care, and in survivors, multidisciplinary rehabilitation involving not only the patient but family and caregivers. In this manuscript, we reviewed recent literature with the aim of understanding and making known the appropriate approach to this complication. A search was conducted for recent literature on the topic mentioned using the keywords "Hypoxic-ischemic brain injury, Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in adults" in the database PubMed of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. The search resulted in 62 articles, the search was delimited with the temporality from 2015 to 2023, 20 were selected, considering those that can be integrated into the themes that make up the structure, that had as references recent literature < 10 years old; those that had information not directly related to the topic or that did not include the subsections to be addressed in the review were not included.

Keywords:

Hypoxic-ischemic brain injury, Anoxic encephalopathy, Anoxic brain injury

Introduction

Hypoxic-ischemic brain injury (HIBI) is a serious medical condition that can have severe consequences on an individual's cognitive, motor, and sensory functions1. HIBI commonly occurs due to a variety of reasons, including cardiac arrest (CA), respiratory failure, near-drowning incidents, severe blood loss, and complications during childbirth. When the brain is deprived of oxygen and nutrients for an extended period, it can result in significant cellular damage and even cell death. However, some advances are being made in this area, and there is a focus on identifying patients with the prospect of improving neurologic morbidity and mortality2, usually intubated and have a history of prolonged resuscitation due to several diagnoses1,2.

-

1Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (adults and children), 2022

-

2Anoxic Encephalopathy, 2023

-

1Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (adults and children), 2022

-

2Anoxic Encephalopathy, 2023

The severity and extent of HIBI depend on various factors, such as the duration and severity of the oxygen deprivation, the age and overall health of the affected individual, and the promptness and effectiveness of medical intervention. In the United States, approximately 180.000-450.000 people (in Europe about 270.000 people) are dying due to sudden cardiac death per year3.

-

3Outcome and prognosis of hypoxic brain damage patients undergoing neurological early rehabilitationBMC Res Notes, 2015

Diagnostic imaging techniques are essential for a proper evaluation while anoxia is a common cause of diffuse cortical and subcortical restricted diffusion, this neuroimaging pattern of brain injury can be observed in a variety of other central nervous system and systemic conditions of varying pathophysiology, severity, and long-term prognosis4. Recovery from HIBI varies significantly among individuals and depends on the extent of brain damage. Some individuals may experience partial or complete recovery, while others may require long-term rehabilitation and support to regain lost functions and improve their quality of life. Ongoing research aims to develop new treatments and interventions to enhance the outcomes of individuals with HIBI. Early recognition, timely medical intervention, and rehabilitation efforts play a vital role in optimizing the prognosis for individuals affected by HIBI1-3. In this manuscript, we present recent literature with the aim of understanding and making known the appropriate approach to this complication.

-

4Neuroimaging mimics of anoxic brain injury:a reviewJ Neuroimaging, 2023

-

1Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (adults and children), 2022

-

3Outcome and prognosis of hypoxic brain damage patients undergoing neurological early rehabilitationBMC Res Notes, 2015

Epidemiology

Hypoxic-ischemic cerebral injury occurs at any age, although the etiology is significantly different1-4. Although surveillance of statistics regarding CA and the neurologic outcome is varied, further studies are needed to determine the differences between in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). Cardiac diseases are the main cause of CAs (82.4%) and subsequent brain damage. In the United States, approximately 180.000-450.000 people (in Europe about 270,000 people) are dying due to sudden cardiac death per year3. In a series of clinical cases reported, the following results were found within the most important etiologies: cardiac infarction (30.1%), cardiac arrhythmia (4.3%), pulmonary embolism (4.3%), respiratory insufficiency (3.2%), attempted suicide (3.2%), Qt syndrome (2.2%), heart injuries (2.2%), intoxication (2.2%), anaphylactic, shock (1.1%), status epilepticus (1.1%), unknown (24.7%), and other cause (21.5%)3. The spectrum of disability resulting from HIBI ranges from complete recovery to coma or even death. Clinical trials showed that 27% of post-hypoxic coma patients regained consciousness within 28 days, 9% remained comatose or in an unresponsive wakefulness syndrome (UWS), and 64% died. In another prospective clinical study, 18.6% of patients stayed in an UWS. Hypoxic-ischemic injury is the most common cause of death in patients who initially survive CA3,4.

-

1Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (adults and children), 2022

-

4Neuroimaging mimics of anoxic brain injury:a reviewJ Neuroimaging, 2023

-

3Outcome and prognosis of hypoxic brain damage patients undergoing neurological early rehabilitationBMC Res Notes, 2015

-

3Outcome and prognosis of hypoxic brain damage patients undergoing neurological early rehabilitationBMC Res Notes, 2015

-

3Outcome and prognosis of hypoxic brain damage patients undergoing neurological early rehabilitationBMC Res Notes, 2015

-

4Neuroimaging mimics of anoxic brain injury:a reviewJ Neuroimaging, 2023

The worldwide prevalence of stroke in 2010 was 33 million, with 16.9 million people having a first stroke, of which 795,000 were American and 1.1 million European. It has been estimated that approximately one-third of people fail to regain upper limb capacity, despite receiving therapy. This has important implications for both individuals and the wider society as reduced upper limb function is associated with dependence and poor quality of life for both patients and carers and impacts on national economies. The incidence rate of HIBI secondary to stroke in Europe is about 235/100,000 population. Outcome data among European countries are very heterogeneous5.

-

5A systematic review of international clinical guidelines for rehabilitation of people with neurological conditions:what recommendations are made for upper limb assessmentFront Neurol, 2019

Definition

It is a syndrome characterized by motor and neuropsychological sequelae secondary to low cerebral blood flow (CBF) and a decrease in arterial oxygen concentration that leads to a loss of cerebral vascular autoregulation and subsequently diffuse brain damage1-5. The severity of the injuries correlates with the duration of oxygen deprivation, and it is estimated that after 4-5 min of anoxia, the lesions are irreversible. Clinical trials showed that 27% of post-hypoxic coma patients regained consciousness within 28 days, 9% remained comatose or in an UWS, and 64% died6,7.

-

1Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (adults and children), 2022

-

5A systematic review of international clinical guidelines for rehabilitation of people with neurological conditions:what recommendations are made for upper limb assessmentFront Neurol, 2019

-

6Biomarkers in hypoxic brain injury:methods, discoveries, and applicationsBiomarkers in trauma, injury and critical care. Biomarkers in disease:methods, discoveries and applications, 2022

-

7Encephalopathic EEG patternsStatPearls, 2023

Diagnosis

Medical history

When performing the initial evaluation it musts take a detailed medical history, including information about the circumstances leading to the suspected HIBI, such as CA, near drowning, or respiratory distress. It is essential to differentiate the clinical scenarios of IHCA from OHCA because the prognosis is totally different6. In the context of the OHCA patient, the circumstances of the CA event, exposure to substances, and chronic and degenerative history must be estimated as precisely as possible, specifying the time that the patient was in impaired alertness and without medical or paramedical assistance.

-

6Biomarkers in hypoxic brain injury:methods, discoveries, and applicationsBiomarkers in trauma, injury and critical care. Biomarkers in disease:methods, discoveries and applications, 2022

In the IHCA patient, we must be exhaustive in identifying the triggering cause and correcting it as precisely as possible, as well as establishing the necessary critical care, aimed at correcting the pathophysiology involved in the trigger.

Physical examination

It is necessary to assess neurological function, motor abilities, reflexes, sensory responses, and other signs of brain injury, and do it several times. One of the most important parts of the clinical assessment is determining whether the patients examination is reliable, or whether it is confounded by the administration of medications. Even medications that are no longer being given, but were administered within the previous few days could still be confounding the examination. Any estimation of prognosis must be delayed until a reliable examination, free of the effects of recent sedatives/analgesics or metabolic abnormalities, is obtained. Not uncommonly, these patients are suffering from multiorgan failure with cardiogenic shock, acute kidney injury, and shock liver. Opioids and benzodiazepines are liberally administered, especially early, and these may need 3-5 days to clear once stopped, particularly in the setting of kidney or liver dysfunction7.

-

7Encephalopathic EEG patternsStatPearls, 2023

Various syndromes are integrated in relation to alterations in the state of consciousness:

akinetic mutism is characterized by the fact that the individual retains his or her waking state, without response to any type of stimulus, and with the absence of spasticity or abnormal reflexes, that is, the cortical-spinal pathways are intact.

INDUCED OR IATROGENIC COMA

It is a state similar to coma, produced by the administration of drugs or substances that reduce metabolism and cerebral flow, favoring the loss of brain stem functions.

OBTUNDATION

Moderate disturbance of wakefulness in which attention is focused on a fixed point.

STUPOR

In this state, there is a loss of verbal command-type responses, but retains an adequate reaction to painful stimuli, accompanied by the ability to discriminate the painful point.

DROWSINESS

It is characterized by the tendency to sleep in which the adequate response to simple and complex verbal commands, and painful stimuli, is preserved. This mental state is characterized by decreased comprehension, coherence, and the ability to reason.

LOCKED IN SYNDROME

It consists of a focal lesion of the ventral pons that is clinically characterized by quadriplegia and anarthria, preservation of the level of wakefulness and the content of consciousness, as well as vertical eye movements and blinking. It is not an alteration of the state of consciousness, but it can be confused with them.

COMA

It comes from the Greek "Koma" which means deep sleep. This state is characterized by the total absence of wakefulness and persistent content of consciousness (greater than an hour to differentiate it from transient states). It includes states in which there is a loss of consciousness itself, of relationships, and of the phenomenon of awakening.

VEGETATIVE STATE

This state is characterized by the recovery of the waking state accompanied by the maintenance of the complete loss of consciousness content after a coma1. In general, the cardiorespiratory functions and the functionality of the cranial nerves are intact.

-

1Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (adults and children), 2022

STATE OF MINIMAL CONSCIOUSNESS

It is a state where there are global alterations of consciousness with elements of wakefulness, that is, there is intermittent evidence of awareness of oneself or the environment.

Electroencephalogram (EEG)

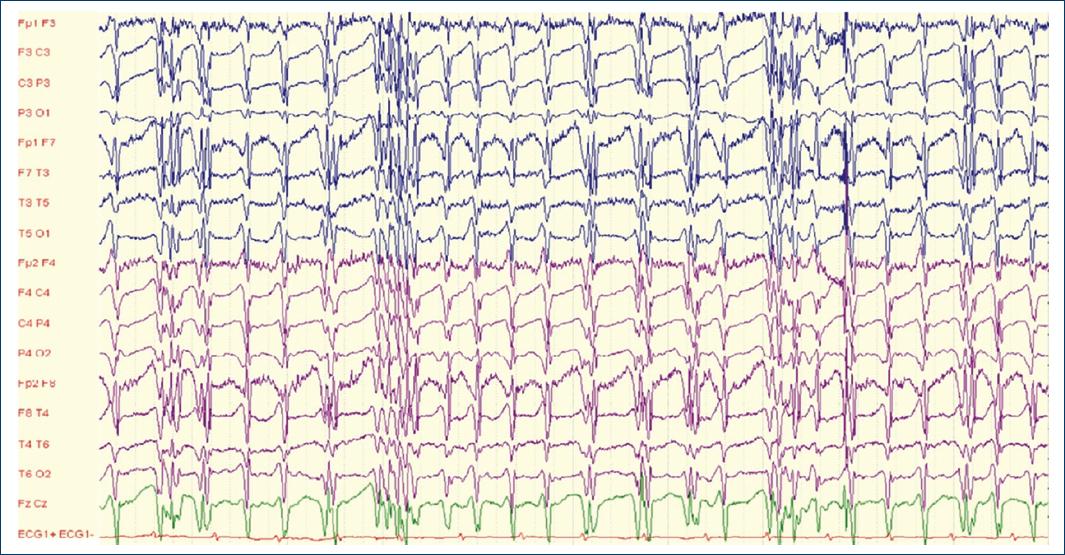

The acute form of encephalopathy can range from mild confusion and delirium to coma. In the more chronic, slowly progressive, or static conditions of encephalopathy, there may be retention of attention initially with loss of cognitive capacity. EEG helps evaluate patients with acute and chronic encephalopathies. The primary role is in differentiating the conditions associated with seizures7.

-

7Encephalopathic EEG patternsStatPearls, 2023

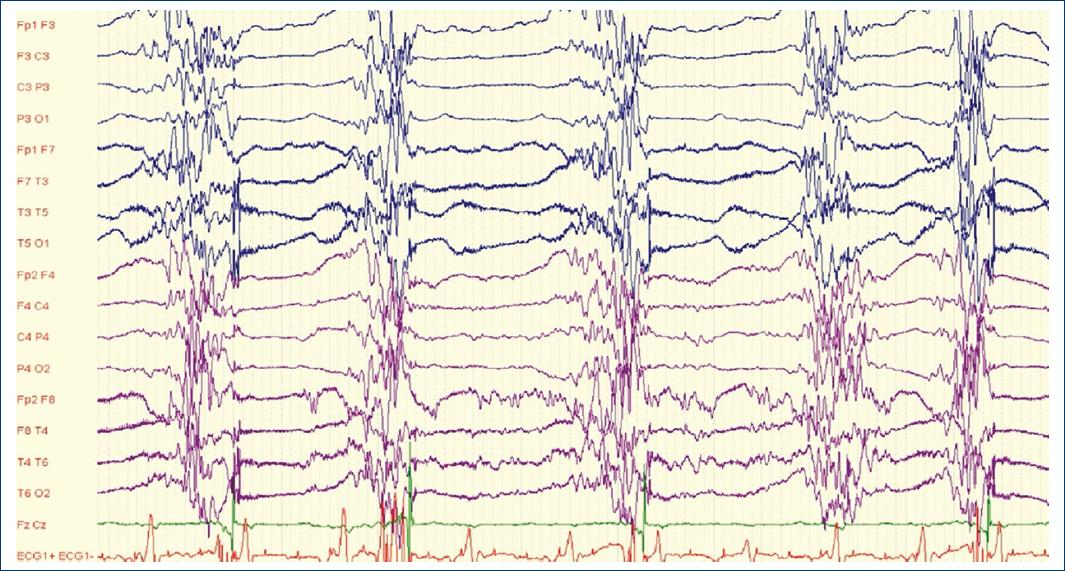

In comatose individuals, diffuse α frequency activity can be seen. When the predominant α activity is noted in the posterior head regions and varies with noxious external stimuli, the etiology of the coma may be secondary to a brainstem lesion; this is associated with a poor prognosis. More diffuse α activity with less reactivity to external stimuli is seen in anoxic injury after CA and is commonly associated with a poor prognosis. When α coma is noted on EEG, the overall outcome depends on the etiology and reactivity to external stimuli, with a better prognosis in toxic encephalopathies and worse in anoxic encephalopathies. Spindle coma consists of paroxysmal bursts of 11-14 Hz activity appearing on a δ background and is usually known to occur in cases of anoxic injury, intracranial hemorrhage, diffuse cerebral insults, and head trauma. EEG pattern spindle coma is associated with the involvement of the pontomesencephalic junction3.

-

3Outcome and prognosis of hypoxic brain damage patients undergoing neurological early rehabilitationBMC Res Notes, 2015

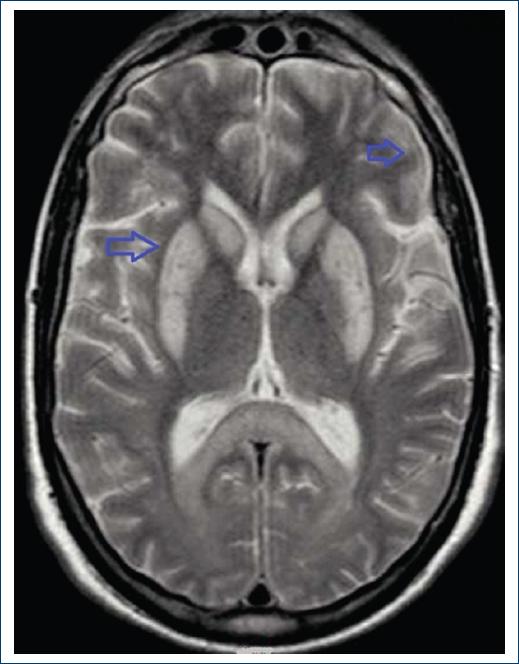

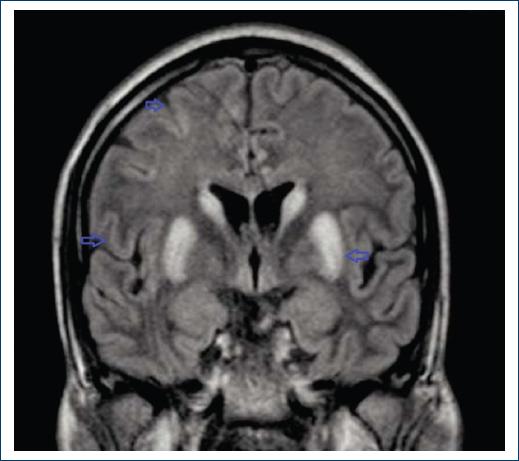

Summarizing: Anoxic or hypoxic injury is encountered in CA, and the extent of brain injury correlates with the severity of anoxia. This includes a wide spectrum from mild, slowing to severe suppression. Poor prognostic EEG findings include α or spindle coma with poor reactivity, burst suppression pattern with longer interburst intervals, and electrocerebral inactivity or silence (Figs. 1 and 2).

Thumbnail

Figure 1

Magnetic resonance imaging axial section in T2 sequence highlights hyperintensity in basal ganglia and dedifferentiation of white and gray matter.

Magnetic resonance imaging axial section in T2 sequence highlights hyperintensity in basal ganglia and dedifferentiation of white and gray matter.

Thumbnail

Figure 2

Magnetic resonance imaging coronal section in fluid-attenuated inversion recovery in addition to hyperintensity in basal ganglia and dedifferentiation of gray and white matter, generalized cerebral edema is observed, giving an image of atrophy of the grooves.

Magnetic resonance imaging coronal section in fluid-attenuated inversion recovery in addition to hyperintensity in basal ganglia and dedifferentiation of gray and white matter, generalized cerebral edema is observed, giving an image of atrophy of the grooves.

Serum biomarkers

Biomarkers can help to identify whether patients have a biological predisposition to respond to a particular therapy. Following hypoxic brain injury, biomarkers are released in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (like Neuron-specific enolase [NSE], S100β, miRNA, etc.), which can be used for prognostication and management purpose6,8. However, a clinical trial explorative analysis showed that early burden of cerebral hypoxia, but not hyperoxia was significantly associated with low brain electrical activity and severe intracranial hemorrhage while none of the blood biomarkers were associated with the burden of either cerebral hypo- or hyperoxia6,8.

-

6Biomarkers in hypoxic brain injury:methods, discoveries, and applicationsBiomarkers in trauma, injury and critical care. Biomarkers in disease:methods, discoveries and applications, 2022

-

8Anoxic-ischemic brain injuryNeurol Clin, 2017

-

6Biomarkers in hypoxic brain injury:methods, discoveries, and applicationsBiomarkers in trauma, injury and critical care. Biomarkers in disease:methods, discoveries and applications, 2022

-

8Anoxic-ischemic brain injuryNeurol Clin, 2017

Here are some important diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers:

NSE: NSE is also known as gamma-enolase or enolase 2 (encoded by ENO2 gene). NSE exists as a homodimer in mature neurons and neuroendocrine cells. NSE elevations in the blood compartment have been documented in severe HIBI secondary to trauma8.

-

8Anoxic-ischemic brain injuryNeurol Clin, 2017

Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1): UCH-L1 is a protein that mainly resides in the neuronal cell body cytoplasm. It was one of the few biomarker candidates identified based on recent proteomic studies8.

-

8Anoxic-ischemic brain injuryNeurol Clin, 2017

S100B protein: S100B is an astroglial 11 kDa calcium-binding protein. It is perhaps the most investigated brain injury biomarker to date. Preclinical animal traumatic brain injury (TBI) model data is present. S100B has been studied in TBI of various severities8.

-

8Anoxic-ischemic brain injuryNeurol Clin, 2017

Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP): GFAP is emerging as the most robust biomarker. GFAP biomarker levels are elevated within 3-34 h in CSF and serum/plasma following severe HIBI and in serum and plasma samples after moderate HIBI8.

-

8Anoxic-ischemic brain injuryNeurol Clin, 2017

αII-spectrin breakdown products/fragments as cell death markers: more recently, C-terminal BDPs of axonal protein αII-spectrin (SBDP150 and SBDP145) produced by calpain during necrosis, and SBDP120 produced by caspase-3 during apoptosis) have been identified as potential cell death biomarkers in both animal and human CSF samples8.

-

8Anoxic-ischemic brain injuryNeurol Clin, 2017

Imaging studies

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

The current literature is limited by heterogeneity of MRI timing and patient selection bias. MRI parameters associated with poor outcome include widespread and persistent cortical DWI abnormalities, the combination of cortical and deep gray matter DWI/fluid-attenuated inversion recovery abnormalities, and severe global apparent diffusion coefficient reduction. It can help identify structural abnormalities, such as ischemic areas, bleeding, or swelling. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DW-MRI) is potentially useful for early prediction of neurologic outcome (i.e., before targeted temperature management) in CA patients. The combination of grey matter to white matter ratio on brain computed tomography (CT) and that on DW-MRI, rather than on each modality alone, appears to improve the sensitivity for predicting neurologic outcome after return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) from CA3,8-10 (Figs. 3 and 4).

-

3Outcome and prognosis of hypoxic brain damage patients undergoing neurological early rehabilitationBMC Res Notes, 2015

-

8Anoxic-ischemic brain injuryNeurol Clin, 2017

-

10Brain imaging in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest:pathophysiological correlates and prognostic propertiesResuscitation, 2018

Thumbnail

Figure 3

Electroencephalogram of an adult patient after prolonged cardiopulmonary resuscitation, presents a burst-suppression type pattern with a poor prognosis.

Electroencephalogram of an adult patient after prolonged cardiopulmonary resuscitation, presents a burst-suppression type pattern with a poor prognosis.

Thumbnail

Figure 4

Electroencephalogram showing periodic generalized epileptiform discharges in patient with hypoxic-ischemic brain injury.

Electroencephalogram showing periodic generalized epileptiform discharges in patient with hypoxic-ischemic brain injury.

CT scan

After 3-5 days in severe cases, global brain edema may be visualized. Several studies have found that the disappearance of the gray/white junction on non-contrast head CT has been associated with poor outcomes and failure to awaken. A multicenter study showed that reduced gray-white matter ratios predict poor outcome with but with extremely low sensitivity (3.5%-6%), limiting its usefulness in clinical practice. Furthermore, including CT findings in a multivariable model with other prognosticators did not improve the accuracy of prognostication10.

-

10Brain imaging in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest:pathophysiological correlates and prognostic propertiesResuscitation, 2018

Treatment/management

The pillar of treatment should be based on prevention, every patient who can potentially be complicated by a CA should have an adequate management of the complication in acute that implies a timely correction of the triggering cause as well as a standardized management of said event by highly qualified personnel.

In the context of neurocritical patient on acute management to reduce the risk of HIBI, several recommendations are suggested.

Taccone et al.11 suggest the following goals:

-

11Use a GHOST-CAPin acute brain injuryCrit Care, 2020

Glucose target levels between 80 and 180 mg/dL may be reasonable.

Hemoglobin target to 7-9-g/dL seems reasonable.

Oxygen targeting a SpO2 between 94% and 97% seems reasonable.

Sodium levels > 135 mEq/L also sodium levels up to 155 mEq/L may be tolerated in such conditions.

Temperature avoids > 38.0°C, due to altered cerebral homeostasis.

Guarantee patient comfort, including control of pain, agitation, anxiety, and shivering.

Arterial blood pressure is the main determinant of CBF. Maintaining a mean arterial pressure (MAP) ≥ 80 mmHg and a cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) ≥ 60 mmHg, MAP targets can be titrated according to repeated neurological examination.

PaCO2 causes changes in CBF (a 4% change in CBF per mmHg change in PaCO2). If intracranial compliance is reduced, any increase in CBF may increase cerebral blood volume, and thereby intracranial pressure (ICP). On the other hand, excessive hyperventilation can result in cerebral ischemia, and PaCO2 < 35 mmHg should be avoided.

Godoy et al.12 suggest the following goals:

-

12"THE MANTLE" bundle for minimizing cerebral hypoxia in severe traumatic brain injuryCrit Care, 2023

Maintain temperature goals 36-37°C (core). Hyperthermia can also yield to cerebral hypoxia due to increased metabolism.

Hemoglobin its optimal levels of Hg remain unknown; however, it seems reasonable to reach and maintain Hg values between 7 and 9 g/dL.

Electrolytes and acid basic status balance is the cornerstone. To ensure that Hg dissociation curve remains within functional ranges (p50 = 26-28 mmHg), to reduce the risk of cerebral ischemia and intracranial hypertension pH: 7.35-7.45, temperature between 36 and 37.5°C, to minimize or treat cerebral edema, it is crucial to maintain a slight hyperosmolar state (serum Na+ 140-150 mEq/L) and to avoid hypotonic fluids.

Metabolism, if it is accelerated, O2 demands increase. Brain metabolism is the main determinant of the rate of cerebral O2 consumption. Oxygen pressure of the brain parenchyma locally reflects the balance between the supply and consumption of O2 and should be maintained at values above 18 mmHg. The venous oxygen saturation obtained from the jugular bulb (SvjO2), globally represents the O2 that returns to the general circulation after being consumed by brain cells and should be maintained at values > 55%.

Arterial blood pressure targets include systolic blood pressure > 100-110 mmHg; normal volemia, diuresis > 30 mL/h, preserved peripheral perfusion, and central venous pressure: 6-10 cm H2O.

Nutrition and glucose control are essential for the damaged brain. Glycemia levels < 110 mg/dL may cause non-ischemic metabolic crises, in contrast, hyperglycemia > 180 mg/dL causes neurotoxic cascades (inflammation, micro thrombosis, edema) and disturbs the homeostasis of the internal environment (hyperosmolarity, dehydration), compromising the immune status, among other alterations.

Target of oxygenation, measures must be taken to achieve PaO2 80-120 mmHg, and SaO2 > 95%.

Lung protective ventilation according to available evidence lung-protective ventilation with a controlled mode, tidal volumes between 6 and 8 mL/kg, minimum respiratory rates to ensure levels of PaCO2 between 35 and 45 mmHg, and FiO2 and PEEP necessary to achieve systemic oxygenation targets as we mentioned above, to prevent mechanical ventilation-induced lung injury (barotrauma, biotrauma, volutrauma) plateau pressure should be kept < 2 cm H2O, driving pressure < 13 cm H2O and mechanical power below 17 J/min. It is recommended not to use routinely hyperventilation and to maintain PaCO2 levels between 35 and 45 mmHg.

Detect and treat cerebral edema guaranteeing intracranial pressure goals. The recommended main targets to be achieved should be the following: a) ICP < 22 mmHg; b) CPP: 55-70 mmHg; c) optic nerve sheath diameter (ONSD) < 5.5 mm; d) pulsatility index (PI) < 1.2; and e) Cerebral CT scan without edema signs. Post-CA clinical interventions should include advanced organ support.

Based on promising results from numerous experimental studies from multiple different laboratories, hypothermia has been viewed as an attractive therapy for several acute neurological diseases. Therapeutic hypothermia has been extensively studied at the experimental level and has shown benefit against a variety of mechanisms of brain injury, including reduction in metabolic activity, glutamate release, inflammation, production of reactive oxygen species, and mitochondrial cytochrome c release. In various experimental models of acute brain diseases, several laboratories have consistently demonstrated that hypothermia ameliorates the extent of brain injuries and improves neurologic function. Based on past experimental research, recent clinical studies have established that therapeutic cooling improves neurological outcome from various acute brain insults, including global ischemia after CA, and neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. For other acute cerebral insults, such as ischemic stroke and TBI, the beneficial effect in clinical settings is now under investigation, and its strong neuroprotective effect has been shown consistently by several laboratories in preclinical models13. Targeted temperature management and mild hypothermia treatment can improve neurological function, maintain brain cell function, and reduce the risk of stress reactions13,14. In humans, hypothermia has been found to be neuroprotective with a significant impact on mortality and long-term functional outcome only in CA and neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Clinical trials have explored the potential role of maintaining normothermia and treating fever in critically ill brain-injured patients, physiologic interactions of thermoregulation, effects of thermal modulation in critically ill patients, proposed mechanisms of action of temperature modulation, and practical aspects of targeted temperature management15.

-

13Therapeutic hypothermia and neuroprotection in acute neurological diseaseCurr Med Chem, 2019

-

13Therapeutic hypothermia and neuroprotection in acute neurological diseaseCurr Med Chem, 2019

-

14Target temperature management and therapeutic hypothermia in sever neuroprotection for traumatic brain injury:clinic value and effect on oxidative stressMedicine (Baltimore), 2023

-

15Targeted temperature management in brain injured patientsNeurosurg Clin N Am, 2018

Rehabilitation and support

A strong consensus was found in favor of assessments being conducted by appropriately trained staff. Patients with difficulties in performance of daily activities should be assessed by a clinician trained in the use of whichever scales are chosen to < ensure consistency of their use within the team and an understanding of their purposes and limitations16.

-

16Clinical neurorehabilitation:using principles of neurological diagnosis, prognosis, and neuroplasticity in assessment and treatment planningSemin Neurol, 2021

There was consensus between the Dutch, UK, and US guidelines that patients should be assessed to enable progress to be monitored throughout recovery and multiple measures to allow for changes in setting, goals, and ability levels. The US guidelines recommend multiple activities with the primary assessing function and secondary including measures of impairment, activity limitation, and quality of life. The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network recommended using a range of assessment tools to assist goal-setting17.

-

17Ten rules for the management of moderate and severe traumatic brain injury during pregnancy:an expert viewpointFront Neurol, 2022

Neuroplasticity is involved in the normal processes of learning, memory, and skill acquisition. This same capacity of brain reorganization with experience supports neural repair after brain damage. Endogenous neuroplasticity in recovery likely has a more sensitive and critical time period to intervention beginning in the late acute and subacute periods of recovery after brain damage, such as TBI or stroke. This suggests that patients are most likely to benefit from rehabilitative interventions that promote neuroplasticity in the early days and weeks after brain injury. A goal of recent investigations has been to find strategies and treatments that may extend and enhance endogenous neuroplasticity. Nevertheless, neuroplasticity can play a role later, even in chronic periods of recovery, with skill learning and improvement in performance. Strategies to restore function and improve compensations have been demonstrated during chronic periods after brain injury. The process of neuroplasticity and brain reorganization with experience, learning, and practice is a lifelong capacity that contributes to learning in an undamaged nervous system, as well as recovery after developing neurological dysfunction17.

-

17Ten rules for the management of moderate and severe traumatic brain injury during pregnancy:an expert viewpointFront Neurol, 2022

Considerations on obstetric patients

We found no differences in this review in the approach to obstetric patients18,19.

-

18Management of severe traumatic brain injury in pregnancy:a body with two livesMalays J Med Sci, 2018

-

19Maternal cardiac arrest in the Netherlands:a nationwide surveillance studyEur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol, 2019

Conclusion

HIBI is the drastic and irreversible result of neurological injury, almost always occurring as a consequence of CA or in patients receiving suboptimal neurocritical care. The diagnosis of this clinical entity is based on a detailed neurological evaluation that includes clinical tests, as well as special studies that include neuroimaging, neurophysiology, metabolic, and biomarker studies. The most important treatment is based on prevention, every health unit must have a rapid response team for brain code, CA code, as well as intensive care units with a team trained to perform timely care and interventions in critical patients, with special emphasis on neurocritical care to prevent or limit the severity of a condition that potentially causes neurological damage. Rehabilitation options for HIBI must involve a multidisciplinary approach, including medical management, physical and occupational therapy, speech therapy, and psychological support for both the patient and their family.

References

-

1Di Muzio B, Majeed A, Kemp W, Abdeldjalil B, Yu Jin T, Gerstenmaier J, et al. Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (adults and children);2022. Available from:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/hypoxic-ischemic-encephalopathy-adults-and-children-1?lang=us Links

-

2Messina Z, Hays Shapshak A, Mills R. Anoxic Encephalopathy. Treasure Island, FL:StatPearls Publishing;2023. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/nbk539833 Links

-

3Heinz UE, Rollnik JD. Outcome and prognosis of hypoxic brain damage patients undergoing neurological early rehabilitation. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:243. Links

-

4Mason Sharma A, Birnhak A, Sanborn E, Bhana N, Kazmi K, Thon J, et al. Neuroimaging mimics of anoxic brain injury:a review. J Neuroimaging. 2023;33:467-76. Links

-

5Burridge J, Alt Murphy M, Buurke J, Feys P, Keller T, Klamroth-Marganska V, et al. A systematic review of international clinical guidelines for rehabilitation of people with neurological conditions:what recommendations are made for upper limb assessment. Front Neurol. 2019;10:567. Links

-

6Gutte S, Azim A, Patnaik R. Biomarkers in hypoxic brain injury:methods, discoveries, and applications. In:Rajendram R, Preedy VR, Patel VB, editors. Biomarkers in trauma, injury and critical care. Biomarkers in disease:methods, discoveries and applications. Cham:Springer;2022. Links

-

7Rayi A, Mandalaneni K. Encephalopathic EEG patterns. In:StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL:StatPearls Publishing;2023. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/nbk564371 [Last accessed on 2023 Mar 04]. Links

-

8Fugate JE. Anoxic-ischemic brain injury. Neurol Clin. 2017;35:601-11. Links

-

9Wang KK, Yang Z, Zhu T, Shi Y, Rubenstein R, Tyndall JA, et al. An update on diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for traumatic brain injury. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2018;18:165-80. Links

-

10Keijzer HM, Hoedemaekers CW, Meijer FJ, Tonino BA, Klijn CJ, Hofmeijer J. Brain imaging in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest:pathophysiological correlates and prognostic properties. Resuscitation. 2018;133:124-36. Links

-

11Taccone FS, De Oliveira Manoel AL, Robba C, Vincent JL. Use a GHOST-CAPin acute brain injury. Crit Care. 2020;24:89. Links

-

12Godoy DA, Murillo-Cabezas F, Suarez JI, Badenes R, Pelosi P, Robba C. "THE MANTLE" bundle for minimizing cerebral hypoxia in severe traumatic brain injury. Crit Care. 2023;27:13. Links

-

13Kurisu K, Kim JY, You J, Yenari MA. Therapeutic hypothermia and neuroprotection in acute neurological disease. Curr Med Chem. 2019;26:5430-55. Links

-

14Wang Y, Huang C, Tian R, Yang X. Target temperature management and therapeutic hypothermia in sever neuroprotection for traumatic brain injury:clinic value and effect on oxidative stress. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102:e32921. Links

-

15Rincon F. Targeted temperature management in brain injured patients. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2018;29:231-53. Links

-

16Katz DI, Dwyer B. Clinical neurorehabilitation:using principles of neurological diagnosis, prognosis, and neuroplasticity in assessment and treatment planning. Semin Neurol. 2021;41:111-23. Links

-

17Di Filippo S, Godoy DA, Manca M, Paolessi C, Bilotta F, Meseguer A, et al. Ten rules for the management of moderate and severe traumatic brain injury during pregnancy:an expert viewpoint. Front Neurol. 2022;13:911460. Links

-

18Kho GS, Abdullah JM. Management of severe traumatic brain injury in pregnancy:a body with two lives. Malays J Med Sci. 2018;25:151-7. Links

-

19Schaap TP, Overtoom E, van den Akker T, Zwart JJ, van Roosmalen J, Bloemenkamp KW. Maternal cardiac arrest in the Netherlands:a nationwide surveillance study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;237:145-50. Links