Introduction

The human body is a set of interconnected systems of great complexity, and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) is one of the most important ones, as it modulates blood pressure by regulating blood volume, sodium and water reabsorption, potassium secretion, and vascular tone. Furthermore, it is involved in inflammatory processes and cell death, thereby playing a key role in cardiovascular and renal diseases1,2.

The primary function of the RAAS is to regulate systemic blood pressure and given its vital functions, it is evident that an alteration in this system could translate into pathological clinical conditions such as hypertension, heart failure, fibrosis, and kidney disease, among others3. Although in the early stages of these diseases, there is compensation due to acute RAAS activation, chronic activation can be harmful as angiotensin II (Ang II) and aldosterone have deleterious renal effects, such as endothelial dysfunction, glomerular dysfunction, increased intraglomerular pressure, tubulointerstitial damage, increased reactive oxygen species (ROS), and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), ultimately promoting cell death processes such as apoptosis, necrosis, or autophagy4-6.

In Mexico, hypertension ranked 10th in morbidity until 2022 and mortality from heart diseases is the leading cause of death, with over 200,000 deaths in 2022. Therefore, both the diagnosis and timely treatment of these conditions are of great importance. Treatment includes lifestyle changes, improved diet, and exercise, which help control these conditions.

On the other hand, once a cardiovascular disease is diagnosed, pharmacological treatment plays a crucial role, and the choice of drugs and their systemic benefits are key considerations for the physician. Clinically, blocking the angiotensin II signaling pathway, a metabolic pathway, involved in cardiovascular pathogenesis, remains one of the therapeutic targets that continue to yield beneficial effects. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II Type 1 receptor antagonists remain the most effective drugs for controlling hypertension in patients.

Typically, RAAS is taught with a focus only on its physiological functions, neglecting the alterations of the system that could lead to pathological conditions. Understanding these alterations and the diseases caused by RAAS overactivation is of clinical importance. Therefore, this article aims to conduct a bibliographic review of existing information on RAAS overactivation and its detrimental renal effects to improve treatment guidelines.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted through a bibliographic search and review of original articles, review articles, and book chapters using the digital databases PubMed, Science Direct, and Scielo, restricting the search from 2017 through 2022. The following keywords were used for article search purposes: "RAAS," "Angiotensin II," "Angiotensin III," "Angiotensin IV," "Cell death," "Apoptosis," "Necrosis," "Necroptosis," "Ferroptosis," and "Kidney injury." In addition, original articles and literature reviews were searched through Google Scholar.

Results

RAAS

RENIN

Renin is an aspartyl protease enzyme that regulates the first step of RAAS by catalyzing the hydrolytic cleavage of angiotensinogen. This enzyme is synthesized in juxtaglomerular cells near the afferent arterioles of the glomeruli and is encoded by the REN gene located on chromosome 1q32, containing 10 exons and 9 introns7,8. Renin mRNA translates into a 406-amino acid polypeptide called pre-prorenin, which undergoes a 23-amino acid cleavage in the rough endoplasmic reticulum to form prorenin, which is then stored and processed in the Golgi apparatus into the active form of renin by a 43-amino acid cleavage at the N-terminal end, either proteolytically (by proprotein convertase 1 or cathepsin B) or non-proteolytically (by the renin/prorenin receptor), resulting in a 340-amino acid polypeptide released by exocytosis8,9.

Renin secretion is regulated by main mechanisms, which are: (1) Changes in renal perfusion pressure and arteriole diameter by renal baroreceptors, (2) changes in Na+ and Cl- concentration sensed by chemoreceptors and macula densa cells, (3) sympathetic pathway stimulation by activation of β1-adrenergic receptors and circulating catecholamines, and (4) negative feedback from Ang II in juxtaglomerular cells5,7,9.

ANGIOTENSINOGEN

Angiotensinogen is a glycoprotein member of the serpin family (serpin 8) produced mainly in the liver, particularly in the peripheral zone of hepatic lobules, but also expressed in the brain, gallbladder, heart, kidney, and adipose tissue. It is encoded by the AGT gene, located on chromosome 1q42.2 containing 6 exons. Angiotensinogen is a 485-amino acid protein with a 33-amino acid signal peptide, featuring a disulfide bridge between cysteines 18 and 138, producing a conformational change allowing renin access for further processing to angiotensin I (Ang I)5,7,10.

Angiotensin II receptors (AT1R and AT2R)

Ang II is the most active peptide of RAAS, produced by the action of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) on the Ang I peptide. Once produced, Ang II acts on two receptors: the angiotensin Type 1 receptor (AT1R) and the angiotensin Type 2 receptor (AT2R)11.

The AT1R is a 359-amino acid protein expressed in adipose tissue, liver, heart, kidney, lung, ovaries, prostate, salivary glands, spleen, thyroid, bladder, adrenal medulla, and placenta, among other tissues12,13. Stimulation of this receptor mainly activates phospholipases C, A2, and D, inhibits adenyl cyclase, activates mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), and stimulates calcium channel opening, leading to increased intracellular calcium, and increased ROS production. The AT1R receptor has pro-inflammatory effects by promoting sodium retention, has vasoconstrictor effects, increases thirst, activates the sympathetic nervous system, stimulates endothelin, aldosterone, and vasopressin secretion, inhibits atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) secretion, and other effects such as participating in platelet aggregation and cardiac contractility11.

The AT2R, on the other hand, is a 363-amino acid protein whose expression is higher in most tissues during the fetal stage, playing an important role in organ development. However, after birth, its expression gradually decreases but can still be expressed in adulthood, mainly in the lungs, vascular endothelium, heart, adrenal medulla, and kidneys13. Activation of this receptor increases the production of bradykinin (BK), nitric oxide (NO), cyclic guanosine monophosphate, forkhead box protein 3, and interleukin 10, while decreasing tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), Fas ligand (FasL), transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1), and caspase 3.13. This receptor produces anti-inflammatory, anti-fibrotic, and anti-apoptotic effects, causes vasodilation, increases diuresis, natriuresis, and reduces oxidative and nitrosative stress, thus improving renal, cardiac, and other organ functions12,13.

Ang II produces its effects by activating AT1R and AT2R; generally, due to the greater distribution of AT1R, Ang II increases systemic blood pressure, has vasoconstrictor effects, increases endothelial permeability, causes fibrosis and apoptosis, inhibits ANP secretion, and stimulates aldosterone secretion13.

Circulating RAAS: classical pathway

RAAS begins with the production of angiotensinogen from the kidney and renin from juxtaglomerular cells due to decreased renal blood flow, low systemic blood pressure, hypovolemia, or sympathetic stimulation1,3. Once in the bloodstream, renin catalyzes the proteolytic cleavage of 10 amino acids from the N-terminal end of the 485-amino acid angiotensinogen to produce a decapeptide called Ang I, a biologically inactive peptide that is subsequently processed by ACE12. ACE is a dipeptidyl-carboxypeptidase enzyme encoded by the ACE gene located on chromosome 17q23.3, primarily expressed in vascular endothelium, proximal renal tubule, neuroepithelial cells, lung, and small intestine. The function of ACE is to cleave two amino acids from the carboxyl terminal end of Ang I to form an octapeptide known as Ang II, the most active molecule in the system3,4,7,11,12.

Aldosterone is a steroid hormone produced mainly in the glomerular zone of the adrenal cortex. Its production is driven by aldosterone synthase (CYP11B2), and its function is based on activating the mineralocorticoid receptor in the distal and collecting ducts, promoting sodium and water reabsorption, potassium secretion, and increasing systemic blood pressure. Aldosterone is also involved in myocardial remodeling, fibrosis, vascular inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and progressive renal dysfunction8,14.

Most significant clinical activity occurs in the above-mentioned process; however, Ang II can still be processed by other enzymes, especially by aminopeptidases. Ang II, through the effect of aminopeptidase A, which removes an amino acid from the N-terminal end, gives rise to a 7-amino acid peptide called Ang III, from which another amino acid can be removed from the N-terminal end to give rise to Ang IV. Alternatively, Ang IV can be formed through the direct action of dipeptidyl-aminopeptidase III (DPPIII) on Ang II11,14. The effects of Ang III and IV are not as well-known as the effects of Ang II; however, it is known that Ang III binds to AT1 and AT2 receptors, with greater affinity to AT2 receptors, producing anti-inflammatory effects, increasing blood pressure similar to Ang II but less prolonged and only when administered centrally, stimulating the secretion of aldosterone and ANP, participating in cell proliferation processes, and playing a cardioprotective role in ischemic disease11,14,15. Ang IV, on the other hand, mediates its effects through its own receptor: AT4 since has low affinity for AT1R and AT2R; it stimulates ANP secretion, has antagonistic effects to Ang II by inhibiting apoptosis and inflammation processes, does not have regulatory effects on blood pressure or aldosterone secretion, and has been seen to have beneficial effects on spatial learning, memory, neuroinflammation, and neuroprotective effects regardless of blood pressure11.

Circulating RAS: alternative pathway

When thinking about the RAS, a linear process usually comes to mind where angiotensinogen is converted to Ang I, and this is transformed into Ang II by ACE; however, there is an alternative pathway of the system in which ACE2 mainly participates. ACE2 is a 805 amino acid-enzyme, encoded by the ACE2 gene located on the Xp22.2 chromosome, and has carboxypeptidase-like action, removing an amino acid from the carboxy-terminal end. ACE2 acts on Ang I to remove an amino acid and give rise to Ang-[1-9]; however, ACE2 has a greater affinity for Ang II, transforming it into the heptapeptide known as Ang-[1-7]. Ang-[1-7] can also be produced by the removal of 2 amino acids by ACE from Ang-[1-9], or produced directly from Ang I by thimet oligopeptidase, prolyl endopeptidase, or neutral endopeptidase16.

Ang-[1-9] mediates its actions through the AT2 receptor, producing antihypertensive effects, vasodilation, stimulating natriuresis, inhibiting cardiovascular remodeling, inflammation, and apoptosis. Ang-[1-7] is considered the most active peptide of the alternative RAS, as it has diverse effects at cerebral, cardiac, renal, pulmonary, endocrine, reproductive, skeletal, hepatic, and vascular levels, but generally, its effects are antagonistic to Ang II, as it does not raise systemic blood pressure, stimulates natriuresis, inhibits apoptosis, produces NO-dependent vasodilation, and has anti-inflammatory effects. These effects are mediated by its binding to the Mas receptor; however, it is also related to AT2 receptors of the classic RAS11,16-18.

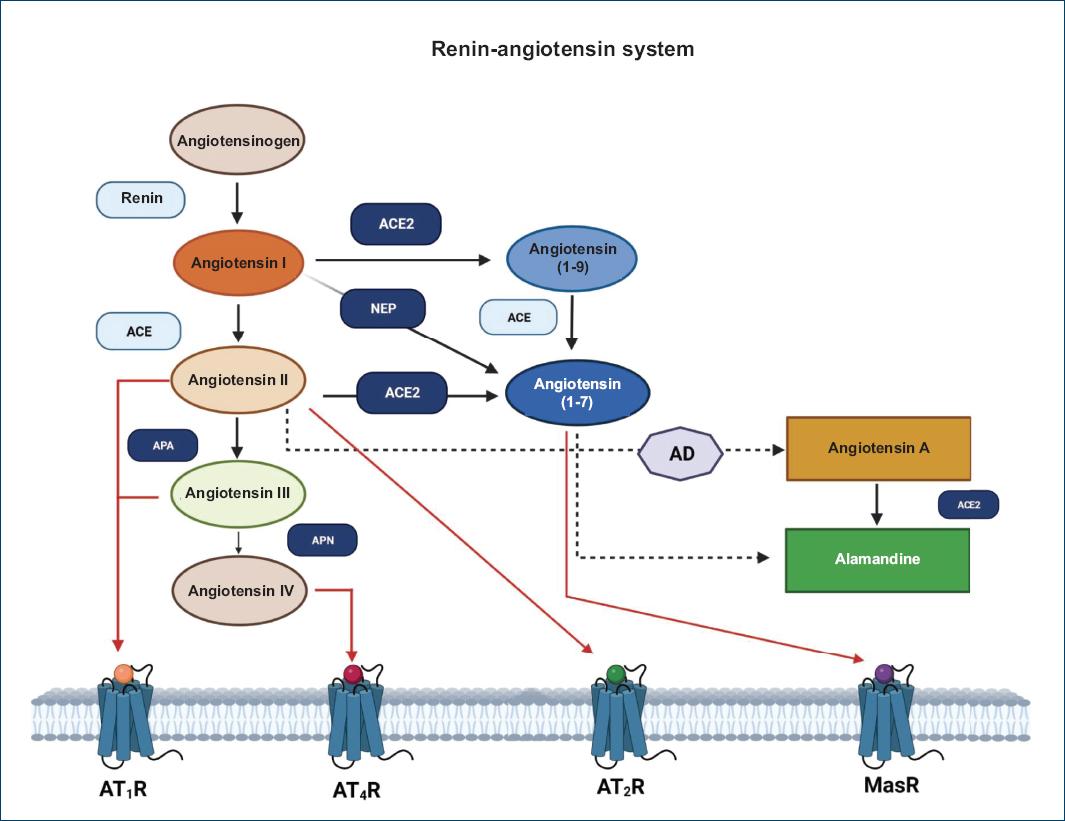

Ang-[1-7] can be transformed into Ang-[1-5] through the removal of two amino acids from the carboxy-terminal end by ACE; the new peptide stimulates ANP secretion by activating the Mas receptor. Another biologically active peptide of the system is alamandine, which is a heptapeptide similar to Ang-[1-7] in which aspartate at position 1 has been replaced by alanine. This can be formed either by the action of decarboxylases on Ang-[1-7] or by ACE2 on angiotensin A (an octapeptide similar to Ang II in which aspartate at position 1 has been replaced by alanine). Alamandine acts on the G protein-coupled receptor type D (MrgD) and has effects similar to the Ang-[1-7]/MasR axis11,16 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Metabolic pathway of the renin-angiotensin II system. This figure shows the enzymatic participants of the classical pathway (renin and ACE, in light blue) and the enzymatic components of the non-classical pathway (ACE II, neprilysin [NEP], aminopeptidase A [APA], and aminopeptidase N [APN]; in indigo blue). Products such as angiotensin II, angiotensin 1-7, angiotensin III, and IV bind to their receptors (red arrow) to produce the previously described effects. Both angiotensin A and alamandine are considered part of the non-classical axis. Image created in BioRender, modified from Ocaranza et al., 202019 and based on bibliographic data.

Cell death

Apoptosis

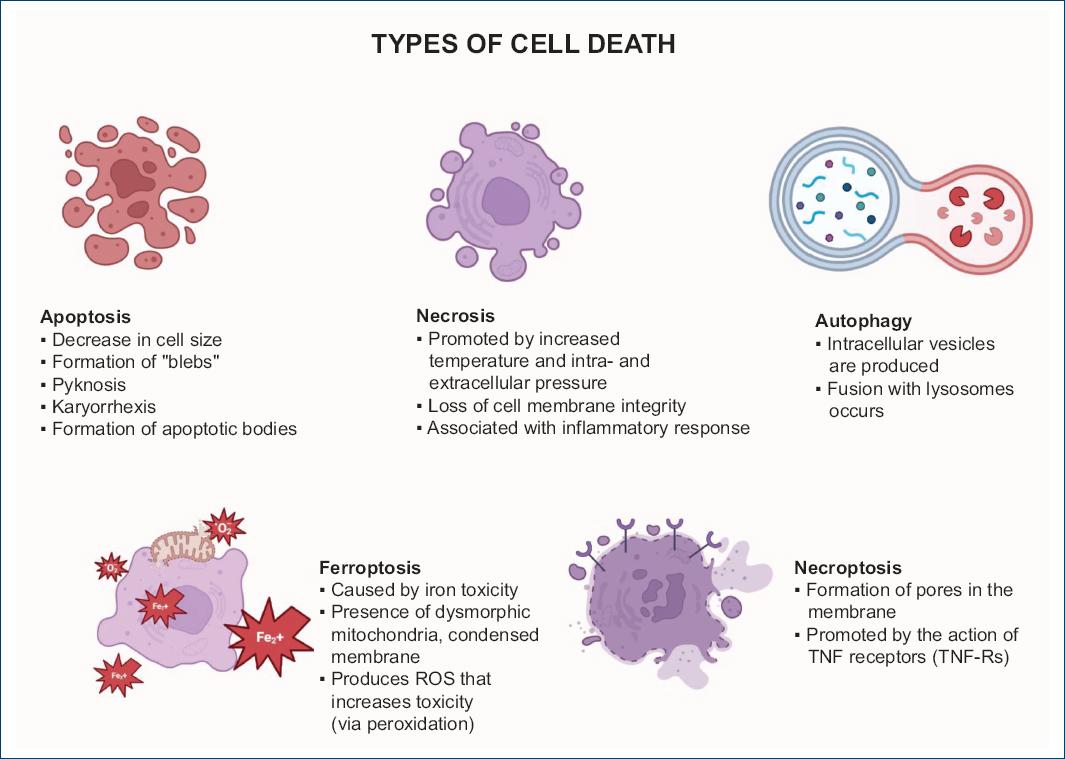

The term apoptosis refers to an orderly sequence of programmed cell death. Apoptosis is a physiological process necessary for tissue homeostasis, as well as embryological and postnatal growth of the organism; however, it is also present in conditions of uncontrolled cell proliferation, DNA damage, and various diseases. Some authors use the term "programmed cell death" when apoptosis occurs as a physiological process and "regulated cell death" when it occurs due to changes in the intra and extracellular environment caused by exogenous disturbances20,21. In general, apoptotic cells are characterized by decreased cell size, formation of plasma membrane blebs, pyknosis (irreversible chromatin condensation), karyorrhexis (nuclear fragmentation), and the formation of apoptotic bodies in which cellular organelles condense to later be phagocytosed without causing a major inflammatory response22,23 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2 Overview of the different types of cell death. This figure illustrates the various processes of cell death described in the literature. (Fe+): iron ion; ROS: reactive oxygen species; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; TNF-Rs: tumor necrosis factor receptors. Image created in BioRender from bibliographic data.

Caspases are necessary for the development of apoptosis; these are cysteine proteases with specificity for cleaving aspartate residues in their substrates. Eighteen caspases have been discovered, which can be categorized into effector caspases (3, 6, and 7), which direct cellular destruction; initiator caspases (2, 8, 9, and 10); and inflammatory caspases (1, 4, and 5). Two are the metabolic pathways through which this type of cell death can occur: the extrinsic or "death receptor" pathway and the intrinsic or mitochondrial pathway20.

In the intrinsic pathway, upon receiving stimuli such as DNA damage, hypoxia, endoplasmic reticulum stress, growth factor deficiency, and hyperthermia, or through the effect of toxins, cells induce the transcription and activation of Bcl2 family proteins, which can be categorized into 3 groups: pro-apoptotic effector proteins (Bax and Bak), anti-apoptotic proteins (Bcl2, Bcl-xl, Mcl-1, BAG, Bcl-W, and A1/BFL-1), and BH3 domain proteins that promote apoptotic activity (Bid, Bim, Bad, Bik, Nix, Puma, Spike, Bnip3, Hrk, Bod, and Noxa). With a greater amount of pro-apoptotic proteins, the permeability of the outer mitochondrial membrane (MOMP) is favored, generating the release of cytochrome C into the cytosol, where it binds with the apoptotic peptidase activating factor 1 (APAF1) and caspase 9, creating the apoptosome, which will generate the activation of effector caspases. Similarly to cytochrome C, the proteins Smac (Diablo) and Omi (HtrA2) are released into the cytoplasm, inhibiting the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP), thereby enhancing the activity of caspases 9 and 324,25.

In the extrinsic pathway, transmembrane receptors called "death receptors" participate; these include the Fas receptor (FasR), tumor necrosis factor receptor type 1 (TNFR-1), tumor necrosis factor receptor type 2 (TNFR-2), TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor type 1 (TRAILR-1), and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor type 2 (TRAILR-2), which belong to the TNF receptor superfamily. Fas and TNF ligands bind forming homotrimers to their respective receptors, activating the cytoplasmic side, binding "death domains" with adaptor proteins such as the TRADD (TNF receptor-associated death domain) and FADD (Fas-associated death domain). This complex activates caspase 8, forming the death-inducing signaling complex, which activates effector caspases like caspase 3, initiating the previously mentioned cell death processes20,22-25.

Autophagy

Autophagy is characterized by the appearance of double-membraned intracellular vesicles called autophagosomes that contain cellular organelles and fuse with lysosomes to form autolysosomes for cellular degradation. Autophagy is a survival mechanism initiated by metabolic stress or damaged organelles, more accompanying than promoting the cell death process. Generally, the autophagy cascade begins with the activation of autophagy-related protein (ATG) 13, Unc-51-like autophagy-activating kinase 1 (ULK1), ATG101, ATG9, promoting the production of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate, resulting in the expansion and fusion of phagophores into the autophagosome21,26.

Necrosis

Contrary to programmed cell death, accidental cell death is discussed, in which, due to extreme environmental conditions such as increased temperature and intracellular and extracellular pressures, the cell loses its structure, producing characteristic morphological changes, such as cell swelling, loss of membrane and organelle integrity, and finally the release of cellular material causing a considerable inflammatory response. Of note that necrosis does not follow any specific biochemical pathways but occurs due to extreme microenvironmental changes21,23,24.

Necroptosis

Historically, necrosis has been considered to not follow any biochemical pathways. However, recently it has been discovered that there are active metabolic pathways related to the morphological changes of necrosis, among these, necroptosis. Necroptosis begins with the binding of TNF to its receptors, specifically TNFR-1. Once binding occurs, complex 1 is formed on the cytoplasmic side, which is composed of TRADD, FADD, receptor-interacting protein kinase (RIPK) 1, and cellular inhibitors of apoptosis proteins (cIAP) 1 and 2. In this complex, cIAP 1 and 2 inhibit RIPK1 through ubiquitination, but when the process of necroptosis begins, the cylindromatosis protein (CYLD) deubiquitinates RIPK1, which causes, in the absence of caspase 8, the binding of RIPK1 to RIPK3. This new complex produces phosphorylation and activation of the mixed lineage kinase domain-like pseudokinase (MLKL), which functions to form pores in the plasma membrane, resulting in cell death27,28.

Ferroptosis

Ferroptosis is another active biochemical pathway related to the morphological changes of necrosis, accompanied by small dysmorphic mitochondria and condensed membranes. Ferroptosis is mainly based on iron-dependent lipotoxicity; where, upon stimulation, the voltage-dependent anion channels (VDAC) -2 and -3 open, favoring the entry of iron into the mitochondria and the generation of ROS. Once in the cytoplasm, lipid peroxidation is favored through enzymatic and non-enzymatic pathways, which through self-amplification results in membrane destruction and consequent cell death29,30 (Fig. 2).

RAS and cell death processes

As mentioned, the main emphasis given to RAS is its physiological function as a regulator of blood pressure. However, it has been associated with various diseases and conditions and cellular alterations when RAS remains chronically activated, being associated with hypertension, acute heart failure, obesity, liver, ocular, and neural diseases, as well as diabetes. However, one of the most affected systems is the renal system, where system hyperactivity has profibrotic and pro-inflammatory effects3,7.

The increase in Ang II concentrations has been associated with a decrease in cell viability and induction of apoptosis at the renal level. This was demonstrated by Peng Y's group (2022), who observed this effect in renal cells of chicken embryos incubated with Ang II [10−5 M] [10−5 M], and in birds administered with sodium chloride (2.5 and 5 g/L); which favored tissue damage (observed as vacuolar degeneration)31.

During ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) events, there are periods of cellular hypoxia, in which the cell, as a survival method, activates the local RAS causing adaptive changes that damage cardiac tissue in the long-haul. These effects are mediated by the activation of AT1R, AT2R, MasR, and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition factor receptor (EMTR). Since the AT1R signaling pathway crosses with tyrosine kinase-mediated pathways, MAPK, and Janus kinase signal transducers and activators of transcription (JAK-STAT), it has been reported that AT1R activation favors ROS production through the NADPH oxidase complex. AT2R has been associated with an increase in NO production at mitochondrial and cytoplasmic levels, as well as RNS through the blockade of the electron transfer chain in the early phase of I/R, while in later stages, it is related to the stimulation of apoptotic processes and inhibition of cell proliferation5. Other markers related to renal failure are linked to cell death processes, with Ang II through AT1R favoring vasoconstriction, producing cellular hypoxia and consequent ROS formation and decreased ATP production. Similarly, AT1R increases intracellular calcium via inositol triphosphate, stimulating VDAC opening, allowing cytochrome C to exit to the cytosol, inducing the intrinsic apoptosis pathway, and iron entry into the mitochondria, thus favoring lipid peroxidation characteristic of ferroptosis. On the other hand, ATP level reduction and DNA damage caused by ROS favor necrosis6. In addition, AT1R stimulates MAPK p38, which activates tumor suppressor protein p53, having a pro-apoptotic effect by increasing the Bax/Bcl2 ratio and stimulating DNase I for DNA degradation. In hepatic, prostate, and podocyte cells, excessive ROS production through AT1R activation is linked to endoplasmic reticulum stress, delta C protein kinase, and MAPK p38, which are associated with apoptotic events. Moreover, MAPK p38 participates in intracellular pH regulation through Na++-H++exchanger isoform 1, which also expresses in podocytes, causing cellular alkalinization upon Ang II stimulation32.

Renin is considered solely as an enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of angiotensinogen to Ang I. However, it has been discovered that renin and prorenin have their receptor, expressed in mesangial cells. On activation, it stimulates MAPK signaling pathways and TGF-β1 overexpression, leading to profibrotic, hypertrophic, and increased apoptotic effects5,8.

Other receptors involved in the apoptosis process are the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs). PPARs are ligand-activated transcription factors from a superfamily of nuclear hormone receptors that regulate body energy metabolism. At present, three isoforms are known: PPARα, PPARβ/δ, and PPARγ, with PPARγ being one of the most studied and of interest, having hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effects, in addition to anti-inflammatory and antihypertensive effects33.

Rosiglitazone (Rgz), an exogenous PPARγ ligand, is a drug from the thiazolidinedione family and was part of the pharmacological regimen for Type 2 diabetes mellitus treatment, being an insulin sensitizer. Part of the pharmacological effects of this tool is due to PPARγ receptor stimulation, known for its role as an exogenous ligand. An example is the work of Efrati et al., who used Rgz in spontaneously hypertensive rats on a salt-rich diet (8%). When receiving Rgz at a dose of 5 mg/kg/day, the rats showed a decrease in blood pressure, Ang II concentration, and mesangial cell death34.

In 2020, our group evaluated the effect of PPARγ stimulation by Rgz action, finding that it reduces systolic blood pressure by regulating RAS in a hypertension model due to aortic coarctation (AoCo). This is because Rgz decreases ACE and AT1R expression and favors AT2R expression, and this phenomenon is PPARγ dependent, suggesting that PPARγ stimulation regulates the antihypertensive axis expression of RAS35.

In other cell death processes such as autophagy, increased Ang-[1-7] expression and its interaction with MasR and AT2R favor autophagy regulation in cardiac protection processes. The interaction of Ang IV with the AT4 receptor antagonizes Ang II effects, inhibiting apoptosis and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy processes. In addition, in I/R injuries, oxidative stress and hypoxia processes favor renal autophagy23,36. In necroptosis, Ang II has been reported to activate this signaling cascade by activating the Fas receptor with its respective ligand in tubular renal cells by activating the RIP3 complex and MLKL phosphorylation, especially in kidneys with chronic diseases. The presence of a RIP1 stabilizer inhibits Ang II effects on necroptosis37.

In ferroptosis, ferrostatin-1 administration (a ferroptosis inhibitor) significantly reduced AT1R expression in astrocyte cultures and ROS production38.

Conclusions

RAS is an important regulatory system in blood pressure homeostasis, with a complex structure interconnected with other body systems and tissues. Chronic overactivation can lead to various deleterious effects and severe health consequences, including liver, renal, cardiac failure, and multiple organ fibrosis. In many of these pathological conditions, cell remodeling and death, given by apoptosis, necrosis, necroptosis, autophagy, and ferroptosis, are related to RAS pathophysiology. Understanding the relationship between RAS and these cell death processes is essential for developing better treatment strategies for diseases where RAS is not normally considered a relevant factor.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)