Introduction

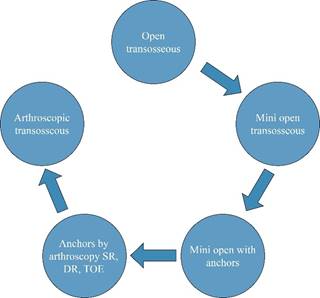

The treatment of rotator cuff injuries was initially described by Dr. Harrison McLaughlin using sutures through transosseous (TO) tunnels in the greater tuberosity of the humerus.1 In recent years, technology has made it possible to perform rotator cuff repair by minimally invasive arthroscopic means, progressively modifying the approach to the shoulder. Although the open technique is no longer the standard of treatment due to technological advances (development of anchors, arthroscopic implants, etc.) apart from the possibility of performing arthroscopic surgery that decreases post-surgical stiffness, size of incisions and allows addressing and diagnosing pathologies that would not be possible or would be technically more demanding with conventional approaches; the pendulum guides us again towards superior transosseous techniques for multiple reasons that will be discussed later (Figure 1). Arthroscopy facilitated the introduction of bone anchors primarily due to their ease of use, high initial fixation strength and profitability for medical device manufacturers. At the time, they were easy to use and effective transosseous devices.

The use of transosseous tunnels is still biomechanically superior to such a degree that some of the configurations intended to be created with the use of arthroscopic anchors are called «transosseous equivalent». It is known that transosseous techniques improve footprint coverage, contact area pressure and generate less movement of the tendon-bone interface. In the 2006 article by Dr. Maxwell Park, it is mentioned a «transosseous-equivalent» surgical technique; an attempt made to recreate through the use of anchors, the cerclage effect provided by the use of true transosseous tunnels, introducing the additional cost of four anchors.2 This technique superficially resembled a TO repair, but introduced overly stiff biomechanics and a novel catastrophic failure mode, the Cho type 2 failure. During the last few years, engineering in sports medicine and arthroscopy has focused on developing the technology used to improve the anchors and the devices used along with them to repair rotator cuff injuries, and very little on developing the technology that allows arthroscopic performance of the biomechanically superior transosseous tunnel surgical technique. In many areas around the world, the cost of biologics, anchors and arthroscopy equipment now exceed the reimbursement for the procedure, reducing access to care for cuff disease.

Although the technology and devices currently exist, dissemination has been limited and scarce. As with any path in search of change, progress is difficult, so it is important to disseminate the advances that have been achieved in different parts of the world to improve the treatment of this type of injury and accessibility to treatment. Currently, arthroscopic rotator cuff repair with the transosseous tunnel technique is possible utilizing special devices without the use of anchors, emphasizing the fact that it is not a transosseous-equivalent technique, but a truly transosseous repair. This has multiple advantages, not only biomechanical -including better clinical results- but also in terms of surgical time, procedures, reduced revisions and greater ease of performance. Additionally, it has great economic advantages, which is of important relevance for the management of this pathology in developing countries, such as in Latin America.

Biomechanics

As with any rotator cuff injury repair, lesion size, fatty infiltration, tendon retraction, and bone quality are key factors in the success of treatment. Comparisons between anchor and transosseous tunnel repair have reported results based on procedures performed on cadaveric models.3

As has been well reported in the literature, the number of sutures through the tendon to be repaired is the most important factor, as it results in a stronger and more resistant configuration.3,4 The new «suture tapes» are a great advance in this field and can be used both in procedures that use anchors and in repairs with transosseous tunnels at the convenience and consideration of the surgeon. Wide-based suture tapes have been shown to be stronger than simple sutures in biomechanical tests that have compared high-strength flat wide-based sutures versus classic rounded sutures (Suture Tape and Fiber Wire).5

Multiple configurations are possible to repair different injury patterns due to the versatility of the technique. The number of sutures may be increased to the point of superseding the physiological need for additional time-zero mechanical strength. Suture number can be varied depending on the surgeon need, tear pattern, time and cost constraints as well as desired skill or complexity level.6 In addition, there are no retained implants at the site of the tendon footprint, which may loosen or migrate, cause imaging artifact and create additional revision concerns.

Rotator cuff repair using transosseous tunnels is characterized by:

Multiple fixation points.

Greater density of fixation points per surface per unit cost.

Use of multiple sutures per tunnel.

Intrinsic «double-row» fixation through the cerclage effect, which maximizes surface area compression and footprint reconstruction.

Greater load distribution and therefore decreased stress in each fixation point.

Higher physiological matching of the modulus of elasticity and cyclic loading behaviour, reducing type 2 failure.

Increased strength of the construct (proportional to the number of high-strength sutures).

Decreased stress at the fixation point in the tendon (therefore fewer type 2 failures due to tendon transection), as well as less tissue strangulation and vascular damage due merely to the crossing of the sutures.

Decrease of pain intensity.

Better value ratio (value = outcomes/cost).

Ability to be used synergistically with other fixation devices currently available in hybrid constructs.

The term «transosseous equivalent» refers to the placement of anchors at the articular margin of the humeral head and lateral anchors at the greater tuberosity of the humerus, simulating the effect of transosseous cerclage. Comparing the distribution of stress exerted per unit area on the repair, the use of a truly transosseous repair distributes the mechanical stress evenly across the tendon, thus the pressure peaks in the tunnel and not on the tissue.7,8 The latter is relevant because a more uniform concentration of biomechanical stress does not restrict blood flow conditions, revascularization nor tendon recovery. It has also been shown that repair with transosseous tunnels reduces the peaks of biomechanical stress exerted in the medial row, which affect long-term healing and the success of the repair.8,9

The biomechanics and biology of the rotator cuff is complex, basically because it consists of transmitting forces from soft and semi-soft tissues such as muscle and tendon to a rigid tissue such as bone. Therefore, affecting the vascularity of the tendon tissue with a construct that is too rigid in the medial row will cause failure of the weaker tissues. On the other hand, a regular transfer of the load and less tissue strangulation allows better blood flow and consequently greater healing capacity. This has been observed in studies using contrast-enhanced ultrasound, comparing rotator cuff repair using an equivalent transosseous technique (anchors in the medial and lateral row) versus true transosseous tunnels, where greater blood flow and vascularity in the tendon have been demonstrated at two months in the construct with true transosseous tunnels.10

Arthroscopic repair of the rotator cuff with anchors versus repair with transosseous tunnels

Multiple studies have compared the arthroscopic transosseous tunnel technique (ATOT) against the transosseous-equivalent technique (TOE) with the use of anchors, finding improvement in postoperative pain, range of motion and results reported by patients in favor of the ATOT.11,12 At twelve months and even at three years of follow-up, no statistically significant differences have been found in the evaluation of the visual analogue scale (VAS), single assessment numeric evaluation (SANE), simple shoulder test (SST), quick disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand (Quick DASH), Constant Score, American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons Score (ASES).13 However, a significant difference in pain at 15 to 21 days postoperatively in favor of the ATOT technique has already been demonstrated in level I randomized clinical studies.13,14,15

This improvement in postoperative pain symptoms has been attributed to a decrease in intraosseous pressure and less plastic deformation of the bone. By tunneling and not using anchors, the intraosseous pressure -which has been related to the pathophysiology of postoperative pain in rotator cuff repair- is released and decreased by the induction of fracture consolidation. In contrast, with the use of conventionally designed suture anchors this pressure cannot be released due to the presence of metallic, biocomposite or polyetheretherketone (PEEK) material eliciting a trauma onto the bone, at the site of insertion.

Regarding the evaluation of the tendon by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed postoperatively, visualization of the tendon is easier in those patients in whom ATOT was used. It has been observed that the retear rate assessed by MRI is the same between both techniques.16 Table 1 summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of the ATOT technique.

Table 1: Advantages and disadvantages of the ATOT technique.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Cost-effective, eliminates the cost of using anchors | Technically demanding at the beginning due to the learning curve (like any surgical technique) |

| Improved rotator cuff footprint biology | Requires use of a new device |

| Possibility of evaluating the rotator cuff completely in follow-up with MRI | — |

| Less postoperative pain | — |

| Possibility of creating multiple attachment points, more efficient load distribution and reduced stress on tissues | — |

| Synergy, hybrid constructs possible (they are not mutually exclusive) | — |

| Type 1 failure check much simpler | — |

ATOT = arthroscopic transosseous tunnel. MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

Concerning failure, comparing ATOT versus TOE it has been observed that TOE constructs tend to fail medially in the myotendinous junction area, while the ATOT construct fails laterally, with the suture crossing the bone at the link between the entrance and exit of the tunnel in those bones with poor quality.17 TOE constructs transfer the tension from the strongest point, which is the bone, to the weakest point, which is the tendon, hence this type of failure is more frequent. On the other hand, with the use of new types of sutures (e.g., Suture Tape) the aforementioned complications with ATOT are rare, and in these cases of failure, if it were necessary to perform a revision of a rotator cuff repair, it is simpler to do so since, as no anchors have been placed, there are no devices to remove from the repair area, neither void nor drill holes generated when removing the anchors from the bone. Ergo, there is a much larger and more versatile footprint area available to work with, as physiologically the tunnel is filled with bone.

A recent 2023 comparative study using a transosseous tunneling system has shed light on the traditional concern of surgeons regarding TO techniques: the concern over suture cut-through the bone tunnel. Jeong et al. recently found in a controlled study that suture cut-through occurred at 8% of TO cases, while suture anchor pull-out was higher at 15%. Retear rate was 5.3% for transosseous repair versus 19.3% for suture anchors. Additionally, peri-implant cyst formation was seen in 16.7% of medial anchor constructs, while no cysts were observed using transosseous technique.18 This may be evidence that design changes in modern devices, as well as indications, and the advent of the reverse arthroplasty have significantly reduced the concern over bone tunnel failure in chronic severe tear patterns.

Value analysis

Although rotator cuff repair using the single-row technique has been shown to be cost-effective, resulting in a net savings of $13,771 over the patient’s lifetime with 94% of patients returning to their activities and work, the total cost of rotator cuff repair surgery has been found to be approximately $5,904.21, of which $3,432.67 is for the cost of the anchors.19,20 When the cost of the devices using the double-row technique was analyzed, the cost of the implants rose to $4,570.25.20,21

In a study conducted by Seidl et al., it was determined that the average difference in cost between TOE and ATOT was $946.61 per surgical procedure, this equals $250 million saved annually when using the ATOT technique.14

In a study conducted by Black et al.22 in 2016, compared the cost of implants and surgical time were compared between the two techniques: transosseous-equivalent and true transosseous without the use of anchors. It was shown that the latter technique generates considerable savings, taking into account that per case an average expense of $1,014.10 is made on implants, which increases depending on the number of anchors used, if they fail or an instrument breaks, opposite to what happens with transosseous tunnels regardless of how many tunnels are used. This gives the transosseous tunnel technique the possibility of better management of the economic resources and at the same time pathology in question resolution, preserving and improving without being inferior in terms of clinical results and surgical time.22

These numbers are especially relevant when considering the health budget in public systems in developing countries such as in Latin America, which is why this analysis should be included within the relevant points of this technique.

There is a learning curve at the commencement of the ATOT technique implementation in practice. On average, an experienced shoulder surgeon takes ten minutes longer in the first surgeries (normal average time 90-98 min.). However, after 25 procedures surgical times are back to normal again.12

All these data explain how limiting the costs of these surgical procedures is convenient for surgeons, insurers, health institutions, the patient and ultimately society in general.

Technique preferred by the authors

There are multiple devices available to perform transosseous tunneling techniques, however, we describe the one preferred by the authors. For a more detailed understanding of the device and technique, we refer readers interested in improving their knowledge of the TransOs Tunneler Shoulder Pro System surgical techniques to the Tensor Surgical website23 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: A) The components of the kit for making transosseous tunnels can be seen. The kit includes the tunneler, the awl and the punch. B) TransOs Tunneler (Tensor Surgical). The hook with the suture passing system can be seen in the distal part of the tunneler. The hollow body of the tunneler, with an exit convergent to the hook, is the same in the distal part that allows the passage of the awl previously loaded with relay suture to be caught by the hook once inside the tunnels. The awl can be seen in the back part of the tunneler.

This tunneler has the main characteristic of being reusable and designed to be operated with one hand. The kit includes a punch to create the medial row of 2.9 mm caliber, the tunneler and an awl that carries the suture relay through the center of the body of the tunneler, simultaneously delivering the suture and compacting the bone tunnel for extra strength. With the punch, a tunnel of 1.9 mm is made in the medial row, the punch is removed, the hook of the tunneler is inserted and the awl is introduced through the body of the tunneler loaded with a relay suture. This high resistance suture is loaded in the tunneler folded in half, so that when it passes through the tunnel and is recovered in one of the portals, it comes out in the form of a loop in which other sutures can be placed. In order that, this first one, when being withdrawn by the ends at the other side of the tunnel, serves as a relay to pass the other sutures through the tunnel path. The awl is impacted with a hammer on the bone to make the tunnel of the lateral row, eliminating the need for power equipment or drilling. The body of the tunneler is used in turn to guide the awl that carries the relay suture to form a tunnel of the lateral row converging with the tunnel of the medial row. The tunneling hook of the tunneler has a suture capture system in the distal part, which once introduced in the tunnel of the medial row it has contact with the awl and the relay suture it carries, catches the relay suture, and the hook of the tunneler must simply be removed from the tunnel of the medial row. As soon as this step is completed, there is a relay suture along the tunnel through which the sutures will be loaded. We prefer three sutures since it is a good balance of strength and speed, but five to six sutures may be introduced per tunnel at the surgeon’s discretion. Whereas the relay suture is retrieved back through the tunnel there will be three sutures inside the tunnel with three medial and three lateral strands which equals a double row configuration with two fixation points. These same steps should be repeated to make the tunnels that are deemed necessary. The awl can be reused as many times as necessary in the same case, however, it is disposable and a new one must be used for each patient. Nevertheless, it is much more cost effective than the use of even a single anchor.

Suture configuration and other applications

Utilizing ATOT allows the surgeon to perform as many configurations as needed, just as mentioned above. It is even possible to make hybrid configurations where the use of an anchor can be added in a «third-row» configuration that could be useful in those cases where patients present osteopenic bone.24 In addition, it is also possible to perform biceps tenodesis with transosseous tunnels, a technique already described in the literature.25 Two of the techniques most commonly used by one of the main exponents of ATOT in the world today are described below, as well as one of the authors’ of this article technique. Two of the techniques most commonly used by one of the main exponents of ATOT in the world today are described below, as well as one of the authors’ of this article technique (Hospital Ángeles Metropolitano, Ciudad de México, México and Center for Sports Medicine and Orthopaedics Chattanooga TN, USA).

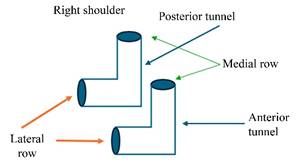

Full transosseous repair (X box configuration)

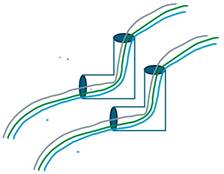

With the patient in the beach chair position, enter the glenohumeral joint through a standard posterior portal. Afterwards, create an anterior portal through the rotator interval. Perform the diagnostic arthroscopy in order to evaluate the lesion. The arthroscope is then mobilized to the subacromial space through the posterior portal. A lateral subacromial portal must be made and a cannula placed through it. Through this portal the bursectomy is performed. Subsequently the arthroscope should be placed in a posterolateral portal for better visualization of the rotator cuff lesion and the footprint area of the greater tuberosity of the humerus should be scarified and stimulated to promote healing of the repair. The TransOs tunneler (Tensor Surgical) is used to tunnel the greater tuberosity -two standard tunnels: anterior and posterior- and pass three sutures through each (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3: Example of the tunnels’ arrangement made in a right shoulder showing the holes corresponding to the medial and lateral row of the anterior and posterior tunnel.

Figure 4: The anterior and posterior tunnels are observed with the triplet of sutures passed inside the tunnels, showing three strands exiting in each hole of the medial row and three strands exiting in each hole of the lateral row.

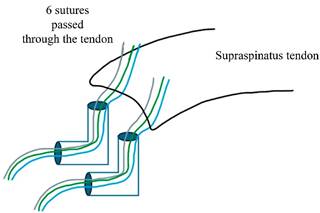

It is preferable to have three sutures or suture tapes of different colors for each tunnel, but the three colors should be the same in each tunnel. For example, if in the anterior tunnel there is a white suture, a blue suture and a green suture, those same three colored sutures should be in the posterior tunnel. The six sutures should be passed through the rotator cuff with an anterograde or retrograde suture passer (Figure 5).

Figure 5: The six strands of the medial row are seen passed through the substance of the supraspinatus tendon in an example of a right shoulder.

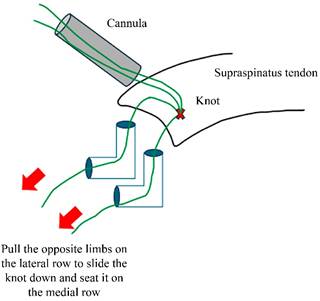

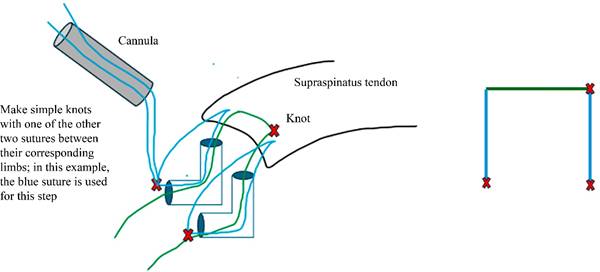

The middle suture or at least one of the same color in each tunnel should be taken and collected through a cannula. The strands coming out of the medial row should be taken. With the sutures out of the cannula, they can be knotted with a double simple knot. Once knotted, pull the ends of the lateral row that correspond to these sutures and the knot will go down through the cannula and settle on the cuff to form the upper part of the box. However, it is also possible to use one of the sutures as a relay suture by using it to form a loop that will be used to pass the other suture through the anterior or posterior tunnel. The latter technique requires a more advanced learning curve but has the advantage that no knots will remain on the cuff (Figure 6). Subsequently, two surgeon’s knots are made on each side joining the end that comes out of the medial row and the end that comes out of the lateral row of the same suture, both in the anterior and posterior tunnels, in order to form the walls of the box (Figure 7).

Figure 6: It can be seen how, using the sutures of the medial row of the same color of each tunnel, a double knot has been made outside the cannula and subsequently introduced to the shoulder and reattached to the cuff by simply pulling the sutures corresponding to the color but on the side of the hole of the lateral row.

Figure 7: The configuration of the sides of the box is shown, simply by knotting the rope of the medial row with the rope of the lateral row of the same color, with simple knots. This is done in both the anterior and posterior tunnels.

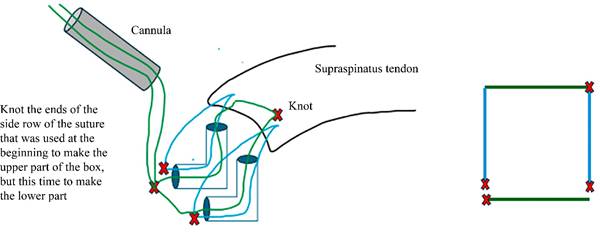

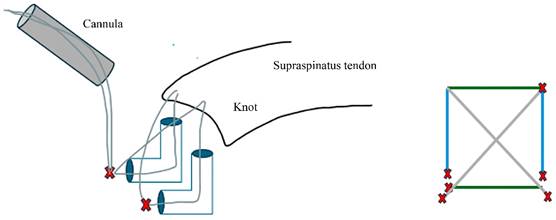

To make the lower part of the box it is necessary to recover through the cannula and knot the two ends of the lateral row corresponding to the sutures with which the upper part of the box was made in the medial row. If the upper part has been made by knotting the two sutures, knotting two ends of two different sutures will form the lower part. If the upper part was made using one of the sutures as relay sutures, then the lower part will be made by knotting the two ends of the same suture when passed through the relay sutures is actually making a cerclage through the two tunnels (Figure 8). Once these steps have been completed, the box is ready and the only pending point is to cross the sutures of the posterior tunnel with those of the anterior tunnel, and this is achieved with the third suture of each tunnel which has not been used until now. Taking the suture ends that have not been used and knotting the end of the lateral row of the posterior tunnel with the end of the medial row of the anterior tunnel, the knot is rested in the lateral row so as not to leave knots on the tendon. Afterwards, the end of the lateral row of the anterior tunnel is knotted with the end of the medial row of the posterior tunnel and in this way the technique is completely transosseous, called X box configuration. As soon as completed, the remaining threads are cut (Figure 9).

Figure 8: It is shown how with the side ropes used to pull the box roof knot at the beginning, a knot is made that can be lowered and reloaded anteriorly or posteriorly over the side row to form the base of the box.

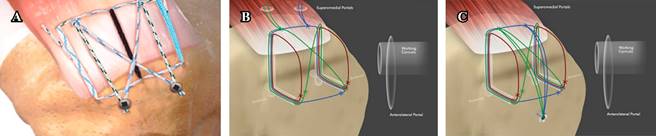

Figure 9: The way in which the remaining sutures should be knotted to form the X configuration is demonstrated, crossing the suture the medial row hole of the anterior tunnel with the suture of the lateral row hole in the posterior tunnel and vice versa. The diagram on the right shows only the part that remains outside the tunnels for didactic purposes, because inside the tunnel there are still the three sutures on each side and it could be confusing.

Hybrid transosseous configuration

This consists of practically the same steps as above, but in this technique, it is important that the «X» knots are oriented on top of the tendon in such a way that the free strands remain on the tendon. Before cutting the sutures, the strands left on top are passed through an anchor without sutures, which is fixed in a more lateral position than the lateral row of tunnels generating a hybrid «triple-row» configuration by the use of transosseous tunnels, reinforced with one or two anchors26 (Figure 10). This structure is useful in those patients who have an osteopenic or osteoporotic bone, besides it has the advantage of being able to be retensioned in a knotless fashion by placing the anchor with cortical augmentation, but with the advantage that no inert material has been left in the healing zone of the footprint.17

Image A taken from Stenson J, et al.26

Images B and C taken from Sanders B.25

Figure 10: A) Image exemplifying the result of a rotator cuff repair with hybrid technique and use of two anchors for a large lesion. B) True transosseous X box in preparation for a hybrid technique with anchor augmentation. The medial tails are left long for incorporation into a lateral row knotless anchor. C) True transosseous hybrid final construct. Five fixation points are achieved with only one anchor. There is no inert material in the healing zone, and the transosseous fixation is independent of the anchor in a «belt and suspenders» fashion. This technique is a salvage for extreme bone loss or osteopenia with no risk of medial anchor pullout.

Conclusions

The arthroscopic transosseous tunnel technique (ATOT) has established itself as an advanced and effective surgical option for rotator cuff repair, providing significant benefits in terms of biomechanics, clinical outcomes, and economic feasibility. Through the elimination of anchors and the use of innovative devices, ATOT has demonstrated increased coverage of the tendon footprint, homogeneous load distribution and reduced mobility at the tendon-bone interface. These factors contribute to improved healing, resulting in a significant reduction in postoperative pain and improved long-term clinical outcomes, which are critical to patients’ quality of life.

From an economic perspective, the adoption of ATOT represents an affordable alternative, especially in developing countries where the cost of anchors may limit access to advanced rotator cuff repair techniques. The technique not only provides biomechanically superior results, but also reduces surgical costs, which could alleviate pressure on public health systems. Studies have shown that ATOT generates significant savings compared to conventional techniques, reinforcing its feasibility in resource-limited settings.

In addition, the implementation of the technique developed by Dr. Brett Sanders, which optimizes the use of specialized sutures, allows for greater versatility and precision in rotator cuff repair, further enhancing the benefits of this technique.25 With its ability to create multiple fixation points and distribute the load more efficiently, ATOT is positioned as an innovative surgical option that not only improves the biomechanics of the repair, but also facilitates rehabilitation and return to function in patients.

In conclusion, ATOT offers a comprehensive surgical solution that combines biomechanical and clinical benefits with an attractive economic proposition. Its expansion in Latin American healthcare systems would not only improve access to advanced treatments, but would also allow substantial cost savings, improving the overall efficiency of available resources in the healthcare sector.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)