The elementome or ionome (Baxter 2015) can be described as a combination of chemical elements or their ratios that constitute the living tissues of organisms (see Sardans & Peñuelas 2014, Leal et al. 2017, Peñuelas et al. 2019, Fernández-Martínez 2021). The metabolic and physiological processes of organisms are sustained by the array of chemical elements that constitute them and can be influenced by the chemical environment in which they develop (Reiners 1986, Sterner & Elser 2002, Benner et al. 2011, Hidaka & Kitayama 2013, Reich 2014, Fernández-Martínez et al. 2021a). The elementome may be understood as the result of evolutionary processes, abiotic conditions, such as climate and nutrients, and biotic interactions (Sardans et al. 2016, Fernández-Martínez 2021, Sardans et al. 2021). Hence, elucidating the elementome of organisms can offer insights into comprehending ecological processes, while also shedding light on the environmental impact on organisms and their evolutionary implications. The elementary composition of plants is a reliable indicator of their functional traits (Wright et al. 2004, Ågren & Weih 2020, Table 1), and the ecological strategies they follow, and thus represents a good predictor of how ecosystems work (Hernández-Vargas et al. 2019, Fernández-Martínez 2021).

Table 1 Leaf elements, their associated biological and functional traits and references. For each element, we visualize the plant's strategy for acquiring or conserving nutrients, known as the leaf economics spectrum.

| Leaf element | Associated function | References | Leaf economics spectrum sensu Wright et al. (2004) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | Blocks for estructural polymers | Sterner & Elser (2002), Kaspari & Powers, (2016), Kaspari (2021). | -- | |

| C | Structural biomolecules, structure, and photosynthesis | Sterner & Elser (2002), Morgan & Conolly (2013), Kaspari & Powers (2016), Kaspari (2021). | Conservation of resources | Hernández-Vargas et al. (2019) and references contained. |

| N | Structural biomolecules, nucleic acids, and proteins | Sterner & Elser (2002), Kaspari & Powers (2016), Ågren & Weih (2020), Kaspari (2021). | Fast acquisition of resources | Hernández-Vargas et al. (2019) and references contained. |

| P | Nucleic acids and proteins | Ågren & Weih (2020). | Fast acquisition of resources | Hernández-Vargas et al. (2019) and references contained. |

| S | Nucleic acids and proteins | Ågren & Weih (2020). | Fast acquisition of resources | Hernández-Vargas comm. pers. |

| K | Structure and photosynthesis, water use and stomatal control efficiency | Benlloch-González et al. (2010), Sardans & Peñuelas (2015), Ågren & Weih (2020). | Fast acquisition of resources | Hernández-Vargas comm. pers. |

| Ca | Structure and photosynthesis, salt and hydric stress, and defense mechanisms | Rengel (1992), Tzortzakis (2010), Patel et al. (2011), Turhan et al. (2013), Ågren & Weih (2020). | Fast acquisition of resources | Hernández-Vargas comm. pers. |

| Mg | Structure and photosynthesis, nucleic acids, and proteins | Ågren & Weih (2020). | Fast acquisition of resources | Hernández-Vargas comm. pers. |

| Fe | Enzymes, cofactor in nitrogenase enzyme | Krouma & Abdelly (2003), Rubio & Ludden (2008), Ågren & Weih (2020). | -- | |

| Zn | Enzymes | Ågren & Weih (2020). | -- | |

| B | Enzymes | Ågren & Weih (2020). | -- | |

| Al | Enzymes | Ågren & Weih (2020). | -- | |

| Mn | Enzymes | Ågren & Weih (2020). | -- |

Species coexistence holds significant importance within ecology, as it provides a pathway for comprehending the mechanisms that sustain biodiversity in ecosystems and facilitate the emergence of new species (Chesson 2000, Levine et al. 2017). However, the mechanisms of coexistence are not yet fully understood, given the logistical complexity in obtaining evidence. We propose that the utilization of the elementary composition of organisms can serve as a tool to explore evidence concerning patterns of chemical composition among coexisting organisms, thereby elucidating the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon. One mechanism that has been suggested to understand the coexistence among species is niche differentiation theory (MacArthur & Levins 1967, Chase & Leibold 2003), and recently for plants and their chemical elements (Ågren & Weih 2020). One issue about the ecological niche is related to the species survival resource requirements in the ecosystem (Hutchinson 1957). The ecological niche theory is partly based on Gause’s model or competitive exclusion model, which states that two species with identical competitive requirements must be differentiated in order to coexist locally (Gause 1934, Gordon 2000). In the case of plant species, it has been indicated that one strategy for coexistence is the differential use of nutrients or elements (Begon et al. 2006, Peñuelas et al. 2008). In this sense, differentiation in the elementome among plants may reflect differentiation in the use of resources and a strategy for coexistence that may result in differentiation in the biogeochemical niche concept of Peñuelas et al. (2008).

The biogeochemical niche refers to the space occupied by the individuals of a species in a hypervolume generated by different element concentrations, which may be associated with the ecological niche (Peñuelas et al. 2008, González et al. 2017, Peñuelas et al. 2019, Sardans et al. 2021). The position in the hypervolume of the biogeochemical niches of each species can change across time according to the biotic and abiotic conditions and the adaptive plasticity of the species (Urbina et al. 2015, Sardans et al. 2016, Peñuelas et al. 2019). Depending on the degree of plasticity of the species elementome, their intra-population variation, and the evolutionary drivers encountered (Leal et al. 2017), the biogeochemical niche can expand, be displaced, concentrate, or become extinct (Sardans & Peñuelas 2014, Sardans et al. 2016, Urbina et al. 2017, Peñuelas et al. 2019). According to Sardans et al. (2021), as the phylogenetic distance of species increases, greater differentiation of the biogeochemical niche can be identified, probably due to differences in environmental conditions between organisms. In addition, coexisting species tend to differentiate their biogeochemical niches to minimize competition compared to non-coexisting species (Urbina et al. 2017). Coexistence among plants may be partly explained by differentiations in their biogeochemical niche.

In Mexico, one of the most important and hyper-diverse semi-arid regions in terms of biodiversity and endemism is the Zapotitlán-Salinas Valley in the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Biosphere Reserve (Rzedowski 1978, Villaseñor et al. 1990, Dávila et al. 2002, Miguel-Talonia et al. 2014). One of the dominant plant families in this valley is the Fabaceae or legumes (Osorio-Beristain et al. 1996, Arias et al. 2000). The Fabaceae comprises species of ecological importance in arid and semi-arid ecosystems since they are considered biogeochemical engineers of the ecosystem (see, Jones et al.1994, Finzi et al. 1998, Perroni-Ventura et al. 2006, 2010) because they promote plant diversity, nutrient cycling and fertility in soils influenced by them. These plant species form fertility islands or resource islands with high concentrations of soil carbon (C) and nitrogen (N), promoting biotic interactions, and providing nesting, refuge, or feeding sites for other organisms (García-Moya & McKell 1970, Tiedemann & Klemmedson 1973, Virginia & Jarrel 1983, Camargo-Ricalde & Dhillion 2003, Perroni-Ventura et al. 2006, Butterfield & Briggs 2009).

In this study, we evaluate the foliar chemical differentiation evidence of seven legumes that coexist in the hyper-diverse ecosystem of Zapotitlán-Salinas Valley. We determine intra- and interspecific variation of foliar elements as C, N, phosphorus (P), hydrogen (H), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), iron (Fe), and zinc (Zn)- of seven legume species Vachellia constricta, Parkinsonia praecox, Mimosa luisana, Neltuma laevigata, Vachellia campechiana, Vachellia bilimekii and Senna wislizeni. We are also interested in knowing whether the differentiation is related to legumes phylogeny.

We hypothesize that there is intra- and interspecific variation in the foliar chemical composition of legumes and that it is related to their phylogeny. This would allow us to assess the existence of differentiation in their biogeochemical niche. Based on Peñuelas et al. (2019); Fernández-Martínez (2021) and Sardans et al. (2021), we hypothesize a poor differentiation in the biogeochemical niche of phylogenetically closer species compared to less closely related species. The underlying premise of differentiation can probably be supported by a differential use of nutrients or elements, and a possible form of coexistence in this ecosystem.

Materials and methods

Study region. The study was conducted in the Zapotitlán-Salinas Valley, located in the western part of the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Biosphere Reserve, which comprises the southeastern part of the state of Puebla and the northern part of the state of Oaxaca in Mexico. The Zapotitlán-Salinas Valley has a surface of approximately 270 km2 (López-Galindo et al. 2003). It is located in the geographic coordinates 18° 20’ 55’’ N and 97° 28’ 28’’ O and has an altitude of 1,481 m asl. It has a semi-dry semi-warm climate with rainfall in the summer (BS1h), with a mean annual temperature of 18 to 22 ºC. The valley receives between 500-600 mm of mean annual rainfall, which is distributed between May and October. The soil is Calcisol according to the IUSS Working Group WRB (2015). It is characterized by being rich in limestone rocks and having a high concentration of salts since it is derived from the Lower Cretaceous marine sediment (Perroni-Ventura et al. 2010). The soil consists of 41 % sand, 37 % silt, and 22 % clay (Perroni-Ventura et al. 2010). The vegetation type is xerophytic scrub, and it is mainly composed of low trees, shrubs, and succulent plants. The vegetation physiognomy consists of low trees, legume shrubs in a five-meter-high stratum, and columnar cacti up to 8-12 m tall. Land use includes seasonal agriculture in small areas and extensive grazing.

Study species. For this study, we selected seven species of the most abundant legumes that coexist in the Zapotitlán-Salinas Valley. The set of species includes one subfamily (Caesalpinioideae), three tribes Cassieae, Schizolobieae, Mimoseae), four sub-clades and five genera (Bruneau et al. 2024). Various phenological strategies and N2 fixation abilities through the capacity or non-capacity of nodulation of their roots can be observed in this set of species. Parkinsonia preacox, S. wislizeni and V. bilimekii do not appear to have the capacity of atmospheric N2 fixation, while N. laevigata has been reported to be facultative (Table 2). In addition, P. preacox and S. wislizeni are deciduous, as well as M. luisana (Table 2).

Table 2 Study species and their ecological characteristics. All species belong to Fabaceae family and Caesalpinoideae subfamily. FI = soil fertility island or resource island, N = Nitrogen, F = Facultative.

| Species | Tribe | Clade | Sub clade | Phenology | Formation of FI | Nodulation/ atmospheric N2 fixation | Distribution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vachellia constricta (Benth) Seigler & Ebinger | Mimoseae | Core mimosoid | Parkia | Evergreen or sub-deciduous | - | Yes | Mexico, United States | Allen & Allen (1981), Rico-Arce (2000), CONABIO (2020), Tropicos (2021), Bruneau et al. (2024). |

| Parkinsonia praecox (Ruiz et Pavón) Hawkins | Schizolobieae | - | - | deciduous | Yes | No | Bolivia, Mexico, | Allen & Allen (1981), Rzedowski & Cálderón de Rzedowski (1997), Perroni-Ventura et al. (2006), Tropicos (2021), Bruneau et al. (2024). |

| Mimosa luisana Brandegee | Mimoseae | Core mimosoid | Mimosa | deciduous | Yes | Yes | Mexico | Allen & Allen (1981), Camargo-Ricalde & Dhillion (2003), Andrade et al. (2007), Tropicos (2021), Bruneau et al. (2024). |

| Neltuma laevigata (Humb. & Bonpl. Ex Willd.) Britton & Rose | Mimoseae | Core mimosoid | Neltuma | Brevi-deciduous or evergreen | Yes | F | Bolivia, Mexico, United States, | Gómez et al. (1970), Allen & Allen (1981), Perroni-Ventura et al. (2006), Andrade et al. (2007), Tropicos (2021), Bruneau et al. (2024). |

| Vachellia campechiana (Mill) Seigler & Ebinger | Mimoseae | Core Mimosoid | Parkia | Evergreen | Yes | Yes | Mexico | Allen & Allen (1981), Arriaga et al. (1994), Rico-Arce (2000), Pinto et al. (2018), Tropicos (2021), Bruneau et al. (2024). |

| Vachellia bilimekii (J.F. Macbr) Seigler & Ebinger | Mimoseae | Core Mimosoid | Parkia | Evergreen | Yes | No | Mexico | Allen & Allen (1981), Rico-Arce (2000), Jiménez-Lobato & Valverde (2006), Tropicos (2021), Bruneau et al. (2024). |

| Senna wislizeni (A. Gray) H.S. Irwin & Barneby | Casieae | - | - | deciduous | - | No | Mexico, United States | Rzedowski & Cálderón de Rzedowski (1997), Tropicos (2021), Bruneau et al. (2024). |

Field work and study sites. Sampling was carried out in August 2020. Sampling sites (n = 10) covered most of the valley area (ca. 45 km2, between 1,400 and 1,600 m asl), and were selected where all species were found at no more than 20 m and no less than 5 m. An exception was the species V. bilimekii and S. wislizeni, which were only included in five points because when one species was present, the other one was absent. All sites represented the heterogeneity of the sampling area. The nutrient concentrations in the bare soil of each site were from 26.9 to 117.0 mg g-1 of C with a mean of 44.8 mg g-1; 4.0 to 10.3 mg g-1 of N with a mean of 6.5 mg g-1; and 0.482 to 0.686 mg g-1 of P with a mean of 0.55 mg g-1. The set of selected individuals included adults with no sign of disease and with a mean height (± SE) of 2.5 ± 0.14 m for V. constricta, 4.2 ± 0.34 m for P. praecox, 3.5 ± 0.27 m for M. luisana, 3.7 ± 0.31 m for N. laevigata, 3.7 ± 0.35 m for V. campechiana, 5.3 ± 1.4 m for V. bilimekii, and 4.3 ± 0.25 m for S. wislizeni. The mean values (± SE) of the crown diameter of these individuals were 5 ± 0.32 m for V. constricta, 6.7 ± 0.56 m for P. praecox, 3.9 ± 0.33 m for M. luisana, 5.3 ± 0.73 m for N. laevigata, 6.6 ± 0.64 m for V. campechiana, 6.8 ± 78 m for V. bilimekii, and 4.4 ± 0.33 m for S. wislizeni.

We collected 10 g of mature and healthy leaves fully exposed to sunlight following the protocol by Cornelissen et al. (2003) to later analyze their elemental chemical composition.

Preparation of samples and elemental analysis. Leaf samples were weighed fresh and then placed in aluminum trays and dried at 60 ºC for 48 h in a Binder World FD023UL-120V forced convection oven and then weighed again dry. The obtained values were used to calculate the humidity percentage. The dry leaves were ground in a Hamilton Beach 80335r grinder and sieved with a mesh size # 40 (0.42 mm) for the elemental analysis.

Total H, C, and N were determined with a Perkin Elmer Series 2,400 elemental analyzer using 0.5 g of sample and following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Total P concentration was obtained by digestion with nitric and perchloric acid and subsequent quantification with vanadomolybdate reagent in a Spectronic 21.D visible light photometer (Milton - Roy, USA). The elements K, Ca, Fe, and Zn were determined by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) in a portable Thermo Scientific NitonXL3TUIYRA analyzer in the National Laboratory of Geochemistry and Mineralogy of UNAM. The concentration of each element is expressed as units of mass (mg g-1 of dry mass).

Data analyses. Leaf elemental composition.- Intraspecific variation of leaf elemental composition was determined by obtaining Pearson’s coefficient of variation for each response variable (H, C, N, P, K, Ca, Fe, and Zn). Interspecific variation of leaf elemental composition was determined by fitting mixed ANOVA models for each response variable (H, C, N, P, K, Ca, Fe, and Zn). The main factors were species (fixed factor) and site (random factor, n = 10). The species with seven levels: V. constricta, V. bilimekii, V. campechiana, N. laevigata, S. wislizenni, P. praecox and M. luisana. When the response variables did not satisfy the assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity, they were rank transformed to reduce the effect of outliers following Conover & Iman (1981). Rank transformation can increase the power of parametric tests when the data are non-normally distributed (Conover & Iman 1981). When the ANOVA models were significant, means were compared using Fisher’s least significant difference test (LSD) with sequential Bonferroni correction (Rice 1989). The alpha value was 0.05 for all cases.

Legume phylogeny.- To determine the phylogenetic relationships between the study species, we obtained the phylogenetic distances and constructed a phylogenetic tree (Peñuelas et al. 2019, Sardans et al. 2021).

Sequences were obtained of the seven legume species from the GenBank database (accessions AF365028.1, AY944537.1, HM020840.1, KF048284.1, HM020802.1, AF522968.1, KT363994.1, DQ344567.1, AB124986.1).

We selected the marker trnL chloroplast intron because it was the only one available for most of the study species. The sequence of the species M. luisana was not found in GenBank, and thus other species of the genus Mimosa were used to obtain the necessary information for phylogenetic reconstruction.

The sequences were aligned using the online version of MAFFT v. 7 (Katoh et al. 2005). The configuration used was “Same as input” for the sections. UPPERCASE/lowercase and Output order. For the section Direction of nucleotide sequences, we selected “Adjust direction according to the first sequence (accurate enough for most cases)”.

The alignments were analyzed by maximum likelihood (ML). The analysis was performed using the IQ-TREE algorithm (Nguyen et al. 2015) in the IQ-TREE web server (Trifinopoulos et al. 2016). The alignments were loaded, and the option “Auto” was selected for the configuration of substitution model selection, which evaluates 22 substitution models. The selected model was TPM3u+F. Node support was calculated with 1,000 ultrafast bootstrap replicates (Hoang et al. 2018). The resulting phylogeny was visualized in Fig Tree v. 1.4.4 and rooted with the species Quercus ilex.

Phylogenetic distances were calculated in R (R Core Team 2024) using the command “cophenetic.phylo” of the ape package and the tree constructed with the IQ-TREE algorithm (Kudo et al. 2019). The phylogenetic distance for M. luisana, was assumed as the average of the phylogenetic distances of species Mimosa pigra and Mimosa strigillosa, which were used for the reconstruction of the phylogenetic tree because the sequence of M. luisana was not found in GenBank.

Differentiation of the biogeochemical niche.- To explore legume species variation in leaf chemical concentrations, and to be able to differentiate their biogeochemical niches, we performed a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) based on a Pearson’s correlation matrix. All statistical analyses were performed in R (R Core Team 2024)

Relationship between phylogeny, elementome, and biogeochemical niche.- To evaluate a possible relationship between the elemental composition of the study species and their phylogeny, a Spearman’s multiple correlation analysis of the concentration of each element with respect to the phylogenetic distance of the species was performed according to Sardans et al. (2016). This analysis is helpful in understanding the possible relationship between the evolutionary history and functional characteristics of plants (Montesinos-Navarro et al. 2015).

Results

Leaf elemental composition. The intraspecific leaf elemental composition showed variation (Table 3). Variation in the light elements (H, C, and N) was lower than 15 %, but variation in the rest of the elements was up to 224 %. Carbon showed the lowest variation (between 2.6 % in individuals of P. preacox and 1.8 % in individuals of S. wislizeni), while the element with the highest variation was Iron with 223.6 % in individuals of S. wislizeni as well as in individuals of V. bilimekii. The coefficient variation of P showed a range from 16.9 % in individuals of V. cochiliacantha to 48.9 % in individuals of M. luisana.

Table 3 Leaf elemental concentrations of legume species sampled in the Zapotitlán Salinas Valley. Mean values (mg g-1) ± standard error (SE) and coefficients of variation (CV, %) of. Fil. Distance = phylogenetic distance obtained for each species based on S. wislizeni. Lower values indicate that the species are phylogenetically closer, and higher values indicate that they are phylogenetically more distant. <LOD = below the limit of detection.

| Species | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable |

S. wislizeni n = 10 |

P. praecox n = 5 |

N. laevigata n = 10 |

V. constricta n = 10 |

||||

| Mean ± SE | CV | Mean ± SE | CV | Mean ± SE | CV | Mean ± SE | CV | |

| H | 63.5 ± 0.5 cd | 1.9 | 58.6 ± 0.5 d | 2.9 | 71.9 ± 0.6 a | 2.7 | 65.8 ± 0.2 bc | 1.2 |

| C | 451 ± 3.7 bc | 1.8 | 438 ± 3.5 c | 2.6 | 500 ± 3.4 a | 2.2 | 468 ± 3.0 b | 1.9 |

| N | 31.7 ± 1.9 ab | 14 | 36.9 ± 1.7 a | 14.9 | 36.0 ± 1.2 a | 10.6 | 34.7 ± 0.8 a | 7.9 |

| P | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 28.1 | 1.04 ± 0.1 | 42.3 | 1.0 ±0.1 | 45.1 | 0.97 ± 0.1 | 32.6 |

| K | 25.2 ± 3.4 ab | 30.2 | 28.6 ± 3.1 a | 34.8 | 26.2 ± 2.2 ab | 27.1 | 24.8 ± 2.0 ab | 24.6 |

| Ca | 93.8 ± 5.6 a | 13.5 | 75.0 ± 4.5 ab | 18.9 | 33.2 ± 3.3 d | 31.7 | 55.85 ± 3.4 bc | 18.5 |

| Fe | 0.037 ± 0.03 ab | 223.6 | < LOD | NA | 0.022 ± 0.01 b | 211.8 | 0.12 ± 0.05 ab | 122.6 |

| Zn | < LOD | NA | 0.005 ± 0.003 | 211 | 0.097 ± 0.01 a | 45.1 | 0.06 ± 0.007 ab | 35.1 |

| Fil. Distance | 0 | 0.02981831 | 0.03828942 | 0.04425946 | ||||

| Species | ||||||||

| Variable |

V. bilimekii n = 5 |

V. campechiana n = 10 |

M. luisana n = 10 |

|||||

| Mean ± SE | CV | Mean ± SE | CV | Mean ± SE | CV | |||

| H | 60.8± 0.5 d | 2.1 | 66.0 ± 0.7 bc | 3.6 | 67.6 ± 1.2 b | 5.8 | ||

| C | 492 ± 5.2 a | 2.4 | 498 ± 3.5 a | 2.2 | 494 ± 2.9 a | 1.9 | ||

| N | 23.7 ± 1.0 b | 10.2 | 35.7 ± 1.4 ab | 13.1 | 32.9 ± 1.1 ab | 11.8 | ||

| P | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 25.5 | 1.5 ± 0.0 | 16.9 | 1.03 ± 0.1 | 48.9 | ||

| K | 17.7± 1.9 b | 24.7 | 24.9 ± 1.6 ab | 20.7 | 18.4 ± 1.4 b | 25.2 | ||

| Ca | 55.8 ± 4.2 abc | 17.2 | 38.2 ± 2.5 d | 20.9 | 44.54 ± 2.5 cd | 18.4 | ||

| Fe | 0.03 ± 0.02 ab | 223.6 | 0.06 ± 0.03 ab | 172.9 | 0.13 ± 0.02 a | 63.5 | ||

| Zn | 0.01 ± 0.006 c | 137.8 | 0.008 ± 0.004 c | 161.1 | 0.04 ± 0.009 b | 67 | ||

| Fil. Distance | 0.04466909 | 0.04858529 | 0.06719764 | |||||

Vachellia bilimekii showed concentration values of C 20 times higher than those of N, while the rest of the species showed values of C between 11 and 15 times higher than those of N. The species N. laevigata, P. praecox, V. constricta and M. luisana showed concentration values of N 30 times higher with respect to P, and the rest of the species showed values of N between 18 and 28 times higher than those of P (Table 3). Iron was the element with the lowest concentration in P. praecox (value too low to be detected by the equipment), while it was Zn in S. wislizeni (value too low to be detected by the equipment).

All elements, except P, showed significant differences between species (Tables 3,4). The highest C value was observed in N. laevigata, V. campechiana, M. luisana and A. bilimekii (Table 3), while the lowest value was observed in S. wislizeni and P. praecox. The highest value of H was observed in P. praecox and the lowest was observed in P. laevigata (Table 3). The highest N value was observed in P. praecox, N. laevigata and A. campechiana, while the lowest one was observed in V. bilimekii. The highest P values were observed in V. campechiana, N. laevigata and V. bilimekii. The lowest Ca value was observed in N. laevigata, and the highest values were observed in S. wislizenni and P. praecox. Similarly, the highest K values were observed in S. wislizenni and P. praecox. In the case of Fe, the highest values were observed in M. luisana and A. constricta, while the highest Zn values were observed in N. laevigata and V. constricta (Table 3).

Table 4 Leaf elemental differences among legume species sampled in the Zapotitlán Salinas Valley Values of F and P from the two-way ANOVA without interaction model.

| Factor | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Site (random factor) | |||

| Response | F | P | F | P |

| H | 32.3 | < 0.0001 | 0.06 | 0.8 |

| C | 30.7 | < 0.0001 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| N | 4.2 | 0.002 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| P | 2.0 | 0.08 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| K | 3.3 | 0.008 | 2.0 | 0.2 |

| Ca | 20.6 | < 0.0001 | 0.09 | 0.8 |

| Fe | 3.7 | < 0.0001 | 1.1 | 0.3 |

| Zn | 26.6 | < 0.0001 | 0.06 | 0.8 |

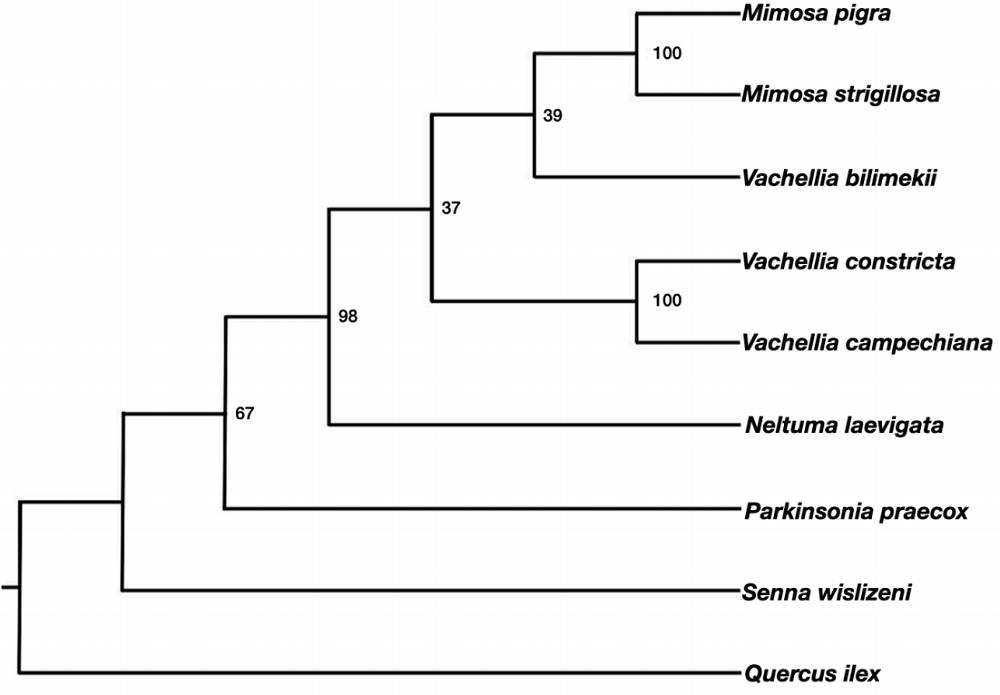

Evolutionary relationships among species. The evolutionary history of the species inferred by maximum likelihood (Figure 1) showed differentiation and grouping of species by tribe . The genera Neltuma, Vachellia, and Mimosa, belonging to the tribe Mimoseae, showed to be more derived, while the genera Senna and Parkinsonia, from the tribe Caseae and Schilozolobieae respectively, showed to be more ancestral.

Figure 1 Phylogenetic tree obtained by maximum likelihood showing the evolutionary relationships of the six legume species studied. The species M. luisana is represented by the species M. pigra and M. strigillosa because its sequence with the selected marker was not found in GenBank. The phylogeny was rooted with the species Quercus ilex.

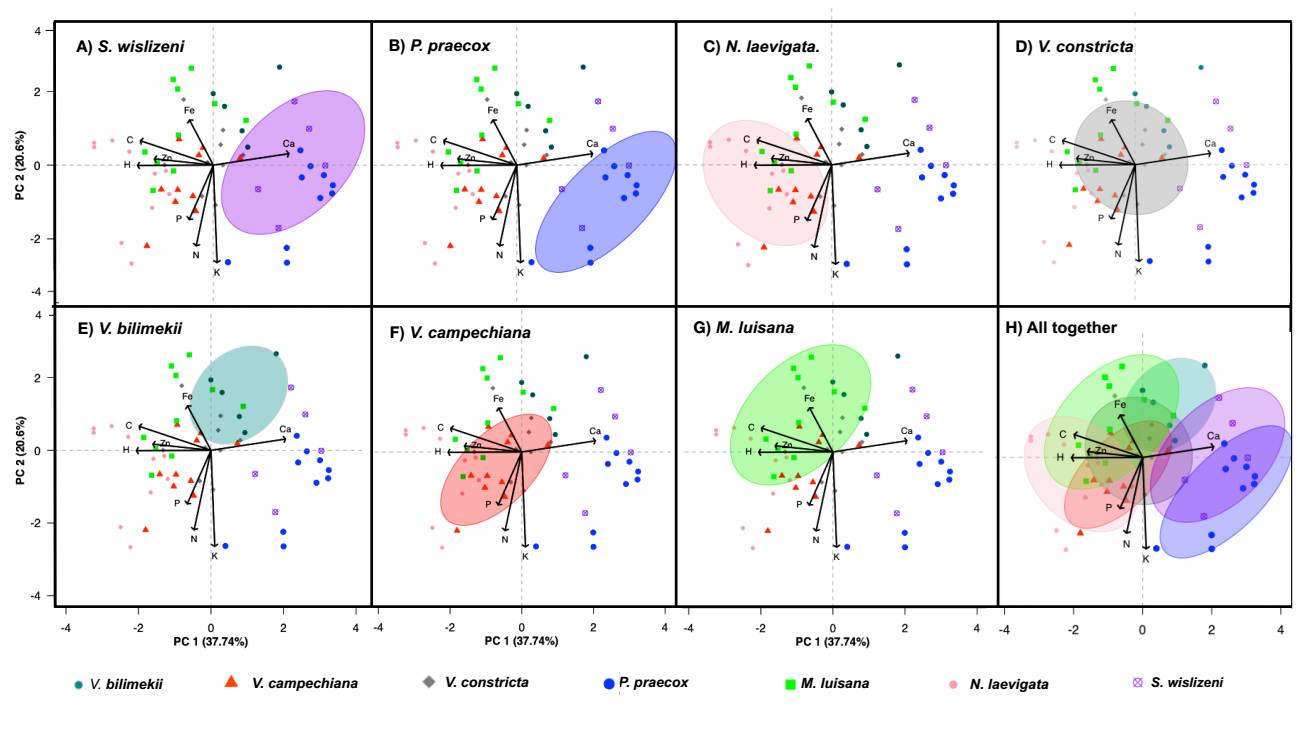

Differentiation of biogeochemical niches. The PCA allowed us to observe the separation of species based on their elementome, with a cumulative explained variance of 58.3 % (Figure 2 A-H). PC1 (37.7 % variance) was positively correlated with Ca (r = 0.51) and negatively correlated with C (r = -0.49) and Zn (r = -0.39). PC2 (20.6 % variance) showed a weak relationship with Fe (r = 0.30) and was negatively correlated with K (r = -0.66) and N (r = -0.54).

Figure 2 Biplot of the biogeochemical niche differentiation of the legume species studied (A-H) based on leaf elementomes of the individuals of each species. Ellipses of different colors represent the theoretical biogeochemical niche obtained through a PCA. Arrows indicate the correlations between elemental concentrations and species. Long arrows indicate a high correlation, while short arrows indicate the opposite.

The results showed that the most ancestral species, S. wislizeni and P. praecox, were mainly related to the element Ca and, to a lesser degree, to K (Figure 2A, B). The species N. laevigata is related to the elements C, Zn, H, P, and, to a lesser degree, to N (Fig. 2C). The species V. bilimekii is related to the elements Fe and Ca (Figure 2E), V. campechiana is mainly related to P, H, and Zn, (Figure 2F), and M. luisana, the most derived species, is related to Fe, C, H, and Zn (Figure 2G). The species V. constricta does not show an obvious affinity for any element (Figure 2D).

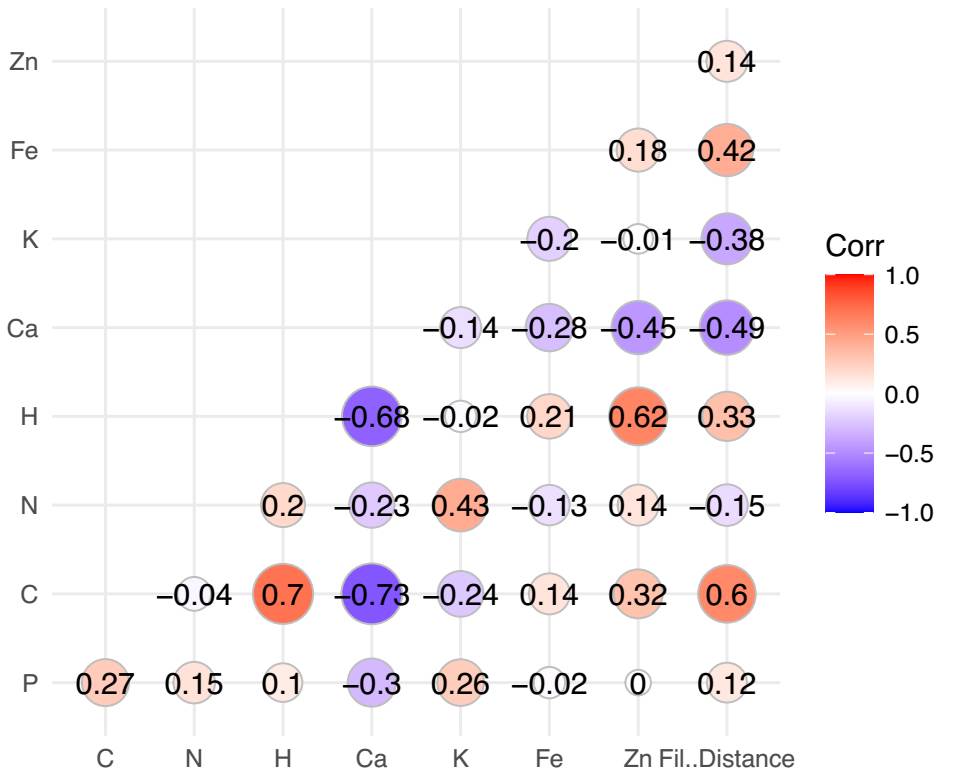

Relationship between phylogeny, elementome, and biogeochemical niche. The multiple correlation analysis between the phylogenetic distances and leaf elemental concentrations of the species showed a positive correlation with C (r = 0.60; P < 0.005) and Fe (r = 0.42; P < 0.005) and a negative correlation with Ca (r = -0.49; P < 0.005) and K (r = -0.38; P < 0.005). This indicates that the more derived species tend to increase C and Fe in their leaves, while the more ancestral species tend to accumulate Ca and K in their leaves (Figure 3). The more ancestral species also showed more expanded biogeochemical niches, while the most derived species showed concentrated biogeochemical niches, except for M. luisana (Figure 2C-H).

Figure 3 Heat map obtained from the correlation between the leaf elemental composition of the legumes and phylogenetic distance. The last column represents the correlation between phylogenetic distance and the leaf elements of that species’ individuals. The more ancestral species showed a negative correlation with C and K, while the more derived species showed a positive correlation with C and Fe.

Discussion

Our results confirm our predictions. We observed evidence of intra- and interspecific variation in leaf elemental composition between species. This variation could be linked to processes associated with differentiation in nutrient acquisition and storage, as well as to the importance of each element in facilitating the construction of biomolecules and metabolic processes. We observed lower variation in light elements (H, C, and N) and higher variation in slightly heavier elements (P, Ca, K, Fe, and Zn). A lower variation in H, C, and N, elemental composition can be explained by their structural use in organisms (Sterner & Elser 2002, Kaspari & Powers 2016, Kaspari 2021). Light elements such as H, C, and N are used as blocks for structural polymers (e.g., cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin) and for most essential biomolecules in plants (e.g., proteins & nucleic acids; Morgan & Conolly 2013). For legumes in ecosystems with low water availability, an interspecific coefficient of variation lower than 18 % has been reported for the elements C, N, and P in species of the same genera as those in the present study and in Regosol soils (Castellanos et al. 2018). In our case, the variation in C, N, and P among species was of 17 % in Calcisol soil, which suggests a similarity in the variation of these elements in this group of dry ecosystems, although with different soil types. The lightest elements (H and C) are directly related to plant structure, and slightly heavier ones (N, P, Ca, K, Fe, and Zn) also in growth (Sterner & Elser 2002, Almodares et al. 2009, Sinclair & Rufty 2012).

The higher variation of the P, Ca, K, Fe, and Zn elements may result from these elements being used by plants for specialized metabolic processes, such as tolerance to different types of stress and defense mechanisms, which are processes that can differ between individuals in their response to biotic and abiotic factors (Kaspari & Powers 2016, Hassan et al. 2017, Thor 2019, Schmidt et al. 2020, Kaspari 2021). The large variation in these elements may also be associated with the functional attributes of legume species such as respiration, photosynthetic efficiency, N fixation, water use efficiency, leaf nutrient resorption capacity, among others specialized mechanisms (Niinemets et al. 1999, Westoby & Wright 2006, Castellanos et al. 2018). High interspecific elemental variation has also been observed in bryophytes, which has been associated with their morphological, functional, and phylogenetic characteristics (Fernández-Martínez et al. 2021a). This variation pattern has also been observed in other plant families, such as Caprifoliaceae, (Merlo et al. 2021) and other groups of organisms, such as microalgae (Symbiodiniaceae, Camp et al. 2022).

The intraspecific variation in leaf P may be explained by variations in soil P availability and the existence of individual differences in P reabsorption in senescing leaves and litter production. Legumes have been reported to be able to reabsorb P from senescing leaves as an essential strategy in maintaining optimal nutrient levels and homeostasis (Cárdenas & Campo 2007, He et al. 2020). P resorption has been reported in Acacia trunca and A. xanthina species in southwestern Australia, with resorption values of up to 40 % (Campos et al. 2013). However, further studies are necessary to confirm this hypothesis such as a species-specific strategy.

A differentiation in the species biogeochemical niche (analogue here to the ecological niche) can be considered a strategy for coexistence in plant species (Peñuelas et al. 2008). Coexisting species, such as legumes in the Zapotitlán Salinas Valley in this case, could differentiate or occupy different niches, and use differential strategies to obtain resources and avoid competing for them (Begon et al. 2006, Peñuelas et al. 2019). However, in the case of these legumes, we have not yet been able to determine the biological implications of their proximity, such as whether facilitation processes may exist between these species. Facilitation processes can be recognized in environments with low water availability such as the semi-desert of Zapotitlán Salinas (Valiente-Banuet et al. 1991, Callaway & Walker1997, Perroni-Ventura et al. 2006, Valiente-Banuet & Verdú 2007, Montesinos-Navarro et al. 2012). A differentiation in the biogeochemical niche has also been reported in bryophytes, where biogeochemical niches of coexisting species are better differentiated compared to non-coexisting species (Fernández-Martínez et al. 2021a). In our case of Zapotitlán Salinas, we observed that there is also less differentiation between the biogeochemical niches of species of the same genus or that are phylogenetically closer (such as we expected according to Peñuelas et al. 2019, Fernández-Martínez 2021 and Sardans et al. 2021). Also, there is a higher differentiation between species of different genera or phylogenetically most distant. This is consistent with what was been previously reported for different communities such as temperate European forests (Sardans et al. 2014, Sardans et al. 2021), Iberian vegetation (Palacio et al. 2022), and bryophyte species (Fernández-Martínez et al. 2021b). A lower differentiation between closer species may be associated with the fact that biogeochemical niches may be phylogenetically conserved (Peñuelas et al. 2019, Fernández-Martínez 2021).

Phylogenetic niche conservatism is the tendency of lineages to retain their niche-related traits through speciation events and over macroevolutionary time (Ackerly 2003), according to the phylogenetic niche conservatism theory (Harvey & Pagel 1991, Münkemüller et al. 2015) and functional redundancy (Jia & Whalen 2020). The phylogenetic niche conservatism theory predicts that two or more microbial species diverging from the same clade will have an overlap in their niches, implying that they are functionally redundant in some of their metabolic processes (Harvey & Pagel 1991). The microbiota has retained for millions of years a highly conserved core set of genes that control redox and biogeochemical reactions essential for life on Earth, and that contributes to its functional redundancy (Jia & Whalen 2020). In this sense, and in the case of plants, the concept of ionome (Baxter 2015, Ågren & Weih 2020) may involve the set of elements, rather than the chemical elements separately, in relation to a core of genes that control these redox reactions and metabolic processes. The chemical elements that make up to the plants may reflect these functional redundancies because of having shared ancestry and they have experienced similar adaptations to environmental conditions (Jia & Whalen 2020). A shared ancestry could also imply that specific biological processes such as genetic, physiological, and ecological constraints restrict niche divergence between closely related species and prevent populations from expanding into new niches (Jia & Whalen 2020).

Biogeochemical niches may also be differentiated according to their degree of expansion, concentration, or displacement, most likely due to the intrinsic plasticity of each species and their evolutionary history (Sardans et al. 2016, Peñuelas et al. 2019, Sardans et al. 2021). In this sense, the environment where the lineage of the species developed can probably be represented in an expanded or concentrated biogeochemical niche, or changes in the environment can promote niche displacement (Peñuelas et al. 2019, Sardans et al. 2021). We observed the relationship between niche expansion or concentration and species ancestry. The most expanded biogeochemical niches were observed in more ancestral species (tribes Caseae and Schizolobieae, Bruneau et al. 2024), whereas the most concentrated biogeochemical niches were observed in more derived species (tribe Mimoseae, Bruneau et al. 2024), except M. luisana. This result may be explained either because ancestral species have higher plasticity in nutrient use and acquisition compared to derived species, or because niche expansion or concentration may be a representation of the necessary optimal ranges that allow individuals to survive and adapt to the ancestral environment. However, further studies are necessary to confirm this hypothesis. Mimosa luisana, the most derived species, appears to have an expanded niche compared to V. constricta, V. campechiana, and V. bilimekii (Figure 2 D-G), likely due to the establishment of the species being associated with a particular or local environment. In Zapotitlán-Salinas, as in ecosystems with low water availability, two main contrasting environments can be distinguished: environments in conditions under vegetation patches and nurse plants and environments in open spaces or bare soil. Seedlings of M. luisana have been reported to establish more abundantly in bare soil and to improve the microhabitat, which allows the establishment of other species under its canopy (Valiente-Banuet et al. 1991, Valiente-Banuet & Verdú 2007, Sortibrán et al. 2014). At the tribe level, we observed niche displacement from the species N. laevigata, which may be associated with a change in the seedling’s establishment conditions possibly low canopy. Seedlings of N. laevigata are commonly observed under the canopy of vegetation patches in certain study site (García-Sánchez et al. 2012).

The pattern of elemental composition observed shows four major groups (1) S. wislizenni and P. praecox (ancestral tribes; Figure 1) with higher Ca and K but lower H and C; (2) N. laevigata, M. luisana, and V. constricta (derived tribe; Figure 1) with higher C, N, P, and Zn; (3) M. luisana and V. constricta with high values of Fe; and (4) V. bilimekii with the highest values of C and P but lower values of N and little K, Zn, and Fe (Table 4). We can observe that the more ancestral legume species tend to enrich their leaves with Ca and K, and this differentiates their biogeochemical niches from the more derived species (Figure 3). It has been reported that the elements Ca and K are usually found at high leaf concentrations in species that colonize calcareous soils, which was observed in species from the Chihuahuan desert and Iberia (Muller et al. 2017, Palacio et al. 2022). It has also been reported that K helps increase water use and stomatal control efficiency (Benlloch-González et al. 2010, Sardans & Peñuelas 2015). Therefore, leaf Ca and K accumulation in these ancestral species may be a strategy for decreasing salt stress and hydric stress (Rengel 1992, Tzortzakis 2010, Patel et al. 2011, Turhan et al. 2013, Rivas-Ubach et al. 2014, 2016). It is possible that the colonization of the environment on the calcareous soil, under sun or shadow environments, of Zapotitlán-Salinas by S. wislizeni and P. praecox was and still is possible because of these leaf attributes. The leaf elementome of these species may be represented in an ancestral environment with a high pH and concentration of cation. The seedlings of P. praecox are successfully established in open spaces in Zapotitlán-Salinas compared with shadow environments (e.i., in open areas (93.3 %), under P. preacox (0 %), and under N. leavigata (6.7 %) Perroni-Ventura et al. 2006), but seedling of S. wislizeni are better in shadow environments (e.i., in open areas (0 %), under P. preacox (29.4 %), and under N. leavigata (70.6 %) Perroni-Ventura et al. 2006). But more specific studies are necessary to test this hypothesis.

The more derived species have biogeochemical niches differentiated by their leaves being enriched with the elements Fe and C (Figure 3). Iron is essential for chlorophyll synthesis and chloroplast stability (Schmidt et al. 2020, Li et al. 2021) and can attract small molecules such as CO2 and water (Kaspari 2021). This may indicate that the more derived species are specializing in increasing their photosynthetic capacity or other specific mechanisms. That also agrees with the high levels of leaf C since C fixation increases with photosynthetic capacity. Iron has been reported to increase nodulation and is a cofactor of the enzyme nitrogenase (Krouma & Abdelly 2003, Rubio & Ludden 2008), and thus the amount of leaf Fe may be related to the functional capacity to form symbiosis with N-fixing bacteria. The more derived species in the present study, belonging to the genera Mimosa, Vachellia, and Neltuma, have this symbiotic capacity (Felker & Clark 1980, Brockwell et al. 2005, Bueno et al. 2010). This suggests that C and Fe are probably important elements in the acquisition of nutrients such as N, either in bare soil environments or within vegetation patches. It would be interesting to test the relationships of functional attributes related to resource acquisition and productivity in relation to biogeochemical niches and their evolutionary implications. A study by Miranda-Jácome et al. (2014) indicates a higher intensity of natural selection in environments on bare soil, compared to environments under vegetation patches due to greater genetic drift in populations in environments on bare soil. However, further studies are necessary to confirm these functional hypotheses and their evolutionary implications. Our data suggests that species have differentiated biogeochemical niches based on their elementome, which may be influenced by their ancestry and the environmental adaptation strategies of each lineage’s species.

Elemental differentiation between species may have ecological implications. Three of the legume species evaluated, P. praecox, N. laevigata (Perroni-Ventura et al. 2006, 2010), and M. luisana (Valiente-Banuet et al. 1991, Valiente-Banuet & Verdú 2007, Sortibrán et al. 2014), have been reported as “nurse species” with differentiation in the levels of fertility of the surface soil under their canopy, with N. laevigata having the highest C and N concentrations in the surface soil compared to P. praecox when only these two legume species form close vegetation patches (Perroni-Ventura et al. 2006, 2010). The level of soil fertility under these legumes is correlated with differences in litter production and has an impact on the communities’ structure under their influence, such as plant richness and biotic interactions (Perroni-Ventura et al. 2006). Given the above, it would be interesting to explore the relationships between the elementome, the biogeochemical niche, the productivity of ecosystems, the richness of the influencing community, and their biotic relations. Therefore, we could reach a more detailed understanding of the influence of legumes on the ecosystem with respect to the differentiation of their elementome and biogeochemical niches. We can conclude that: i) There are differentiations in the leaf elementomes and biogeochemical niches of legume species that are coexisting in the Zapotitlán-Salinas Valley. This suggest that foliar elemental composition may be a fingerprint trait of their ecological and evolutionary history related to nutrient assimilation and acquisition. Consequently, species of the same genus showed less differences compared to most distant species, and more ancestral species showed higher leaf Ca and K concentrations, while more derived species showed higher C and Fe concentrations. Also, a leaf elementome niche differentiation of legumes may have ecological and evolutionary implications in plant communities of this dry ecosystem since they have a strong influence in ecosystem biogeochemical functioning.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)