Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista bio ciencias

versión On-line ISSN 2007-3380

Revista bio ciencias vol.8 Tepic 2021 Epub 04-Oct-2021

https://doi.org/10.15741/revbio.08.e1054

Original articles

Species composition and income from coastal fishing mollusks on the Costa Grande of Guerrero Mexico

1 Facultad de Ecología Marina, Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero. Acapulco, Guerrero, México.

2 Laboratorio de Ecología de Invertebrados del Departamento de Estudios para el Desarrollo Sustentable de Zonas Costeras, Centro Universitario de la Costa Sur. Universidad de Guadalajara. Gómez Farías Núm. 82, San Patricio-Melaque, Jalisco, México.

3 Escuela Superior de Desarrollo Sustentable, Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero. Tecpan de Galeana, Guerrero, México.

4 Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas. Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. San Nicolás de los Garza, Nuevo León, México.

Mollusks are a valuable food source and have a high commercial value. In Guerrero, Mexico, this natural resource is at risk due to inadequate exploitation and the lack of biological and fisheries studies. This research focused on determining which species are caught for commercial purposes and looking for information on the captures of mollusks made by artisanal fisheries. The sampling took place from May to December 2017, and consisted of visiting the Cooperative Fisheries Production Societies (CFPS) as well as places where mollusks are commercialized, where species were identified and quantified in situ. A total of 1,184 organisms were examined, 24 species were identified. The species Striostrea prismatica, Trochita trochiformis and Hexaplex princeps are the ones with the highest volume of catch and are also the ones that generate the highest economic income in the region.

Keywords: Artisanal fisheries; mollusks; commercial importance; Fish Coop Units

Los moluscos son una valiosa fuente de alimento y tienen un alto valor comercial. En Guerrero, México, este recurso natural está en riesgo debido a una explotación inadecuada y la falta de estudios biológicos y pesqueros. Esta investigación se centró en determinar qué especies se capturan con fines comerciales y buscar información sobre las capturas de moluscos realizadas por las pesquerías artesanales. El muestreo se desarrolló de mayo a diciembre de 2017, consistió en visitar las Sociedades Cooperativas de Producción Pesquera (CFPS) así como lugares donde se expenden moluscos, donde se procedió a identificar y cuantificar especies in situ. Se examinaron un total de 1,184 organismos, se identificaron 24 especies. Las especies Striostrea prismatica, Trochita trochiformis y Hexaplex princeps son las de mayor volumen de captura y también son las que generan mayores ingresos económicos en la región.

Palabras clave: Pesca artesanal; moluscos; importancia comercial; cooperativas pesqueras

Introduction

Mollusks are one of the most important food resources in Mexico, representing approximately 11.13 % of fisheries and 23.24 % of aquaculture production. The Mexican Pacific contributes 8.35 % of the catch and 2.42 % of the culture of these organisms (Ríos-Jara et al., 2008). On Guerrero state offshore, mollusks are an essential resource in coastal fisheries and are highly valued, generate important income and contribute to the food security of hundreds of people (Castro-Mondragon et al., 2016). In Guerrero there are 97 coastal fishing Cooperative Fisheries Production Societies (CFPS) registered. In the Costa Grande 47 Cooperative Societies land their products in 19 arrival sites, where there are species with high commercial value such as red snapper, snapper, shark, lobster, octopus, oyster, snails and oysters among others. In the region, the municipality of “La Unión” has a greater number of sites to land their fishery products, the area has a narrow continental shelf that widens due to the transport of sediments in the “Balsas” River delta, in this area most of the cooperatives are dedicated mainly to the capture of scale fish, and mollusks in a smaller percentage (Gutiérrez & Cabrera, 2012).

The capture of marine species in the state is regulated through the registration of fishing permits with a catch regime for scale fish, rock oyster, snail, sea roach, lobster or shark; the largest number of fishing permits is concentrated in the cooperatives located in the municipalities of “La Unión” and “Acapulco” with 64 % of the CFPS (Morales-Pacheco et al., 2010). From the total number of cooperatives registered for the state (97), approximately 30 of them have a valid permit for catching oysters, conch or sea roach. In the “Costa Grande” 10 CFPS have permits for catching some type of mollusk (CONAPESCA, 2016).

In the state of Guerrero, coastal fishing lacks special infrastructure; panga-type boats are used, which can beach and/or land their products on a wide variety of beaches. The main methods used in coastal mollusk fishing are free diving and, much less frequently, semi-autonomous diving with the use of a compressor. Few places along the coast have collection centers for fish products that facilitate both the activity and commercialization. (Castro-Mondragón et al., 2015; Galeana-Rebolledo et al., 2018).

In the southern Mexican Pacific, there is little information on the species of mollusks that are subject to coastal fishing and the current status of their populations is unknown, some of the existing studies are those carried out for the coasts of Chiapas and Oaxaca (Ríos-Jara et al., 2008), and Michoacán offshore (Gorrostieta-Hurtado y Trujillo-Toledo, 2012). Particularly in these areas, mollusks are caught in an artisanal manner for self-consumption, and are only marketed locally (Ríos-Jara et al., 2008).

In Guerrero state, although there are reports on exploited fishery resources, the data and information provided on commercially fished mollusk species is limited and most of the studies that address this issue have been carried out in the Acapulco and Costa Chica regions (Galeana-Rebolledo et al., 2007; Villegas-Maldonado et al., 2007; Flores-Garza et al., 2012; García-Ibáñez et al., 2013; Olea-de la Cruz et al., 2013; Torreblanca-Ramírez et al., 2014; Castro-Mondragon et al., 2015; Castro-Mondragon et al., 2016; Galeana-Rebolledo et al., 2018).

In the Costa Grande region, information on mollusks caught by coastal fishing is scarce, including the work done by Baqueiro & Stuardo (1976), who made observations on the biology, ecology and exploitation of three species of clams, Megapitaria aurantiaca (Sowerby, 1831), M. squalida (Sowerby, 1835) and Dosinia ponderosa (Gray, 1838), thus recognizing the high commercial value of these three species for the Zihuatanejo Bay and Ixtapa Guerrero Island fisheries. Moreover, based on an analysis of the gonad cycle and minimum catch sizes, they propose recommendations for a controlled exploitation, with alternating closures within the exploitation banks, in addition to the publication of Gutiérrez & Cabrera (2012), who described some of the species of mollusks that are captured for commercialization and some additional information reported by fishermen in the region.

Due to the lack of information regarding the current state of the mollusk fishery in the Costa Grande, this research aimed to determine the richness of mollusk species caught by coastal fishing, the most important species caught, and which species generate the greatest economic income in the region.

Material and Methods

Study Area

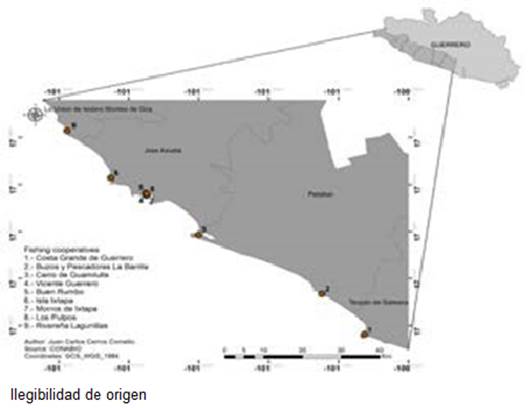

The Costa Grande region is located in the southwestern part of the Mexican state of Guerrero, between (16°53’56” to 17°54’00” N and 99°58’26” to 102°09’50” W). It is composed of seven municipalities of which only six (Coyuca de Benítez, Benito Juárez, Tecpan de Galeana, Petatlán, Teniente José Azueta and La Unión de Isidoro Montes de Oca) border the Pacific Ocean (Figure 1). The Costa Grande has approximately 260 kilometers of coastline, where fishing activity takes place.

The coastal zone of the state of Guerrero has a tropical sub-humid Aw climate. The annual temperature variation is less than or equal to 5 °C, with an annual average of 27.5 °C. In the coastal zone, tidal conditions show a mixed type pattern, with two high and two low tides in a 24-hour period; these characteristics allow fishing activity to be carried out during most of the year (García, 1973).

This research was carried out in four of the coastal municipalities of the Costa Grande region; Tecpan de Galeana, Petatlán, José Azueta and La Unión de Isidoro Montes de Oca, where nine cooperatives dedicated to mollusk fishing are located (Figure 1, Table 1).

Figure 1 Geographical location of the Costa Grande de Guerrero region and the Cooperative Fisheries Production Societies (CFPS).

Table 1 General data of the Fisheries Production Cooperative Societies analyzed in the Costa Grande region of Guerrero state.

| Cooperative | Location | Municipality | N.S. | Permission record |

Fishing regime |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Costa Grande de Guerrero | Puerto Vicente Guerrero | Tecpan de Galeana | 10 | 11201356001 | Ostión de roca |

| Buzos y Pescadores La Barrita |

Playa La Barrita | Tecpan de Galeana | 12 | ------- | -------- |

| Cerro de Guamilulle | Barra de Potosí | Petatlán | 15 | 11202156004 | Ostión de roca |

| Vicente Guerrero | Zihuatanejo | José Azueta | 27 | 11202156014 | Ostión de roca |

| Buen Rumbo | Zihuatanejo | José Azueta | 36 | 11202156027 | Ostión de roca |

| Isla de Ixtapa | Zihuatanejo | José Azueta | 20 | 11202156020 | Ostión de roca |

| Los Pulpos | Zihuatanejo | José Azueta | 20 | 11202156017 | Ostión de roca |

| Morros de Ixtapa | Las Salinas | José Azueta | 19 | 11202156019 | Ostión de roca |

| Rivereña Lagunillas | La Majahua | La Unión | 24 | 11202156009 | Ostión de roca |

N.S. = number of members that belong to each fishing cooperative.

Fieldwork and data analysis

Fieldwork was carried out from May to December 2017. To learn about the species richness of mollusks caught by coastal fishing, visits were made to the arrival sites. To complement this information, restaurants in the region that sell seafood were visited. To avoid confusion with the place of origin of the mollusks sold in restaurants, the owner or manager of the restaurant was interviewed, who previously asked the fisherman for the origin of the catches; on other occasions the information was requested directly from the fisherman.

To develop the species inventory, the fishermen were asked to allow the fishermen to observe the product of their catches to identify the species in situ. Specimens that could not be identified were taken to the laboratory for correct taxonomic categorization employing specialized literature (Keen, 1971; Kaas et al., 2006; Coan & Valentich-Scott, 2012). The nomenclature was updated according to Skoglund (2002) and the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS, 2019). Specimens were deposited in the COMUAGRO mollusk collection, located at the Faculty of Marine Ecology of the Autonomous University of Guerrero.

To estimate the amount of organisms caught, determine which species are the most important and which are the most commercially valuable, 35 surveys were applied to fishermen in the region. The inclusion criterion to be survey was that the fisherman belonged to a CFPS in the region. The sample size corresponded to the number of fishermen who were willing to be interviewed, trying to obtain at least three different surveys for each of the CFPS analyzed.

The survey items that served as the basis for estimating the parameters were the following: 1. What species do you catch most frequently?; 2. How many organisms per species do you catch on a labor day?; 3. How many days do you work per week?; and 4 What is the length of the catching season for each species?.

The unit of measurement with which the catch data were recorded was the dozen organisms per species, which is the measure with which the fisherman quantifies his catch. The species that recorded the highest catches were classified as “target species of the fishery”.

To estimate the average number of days worked by a fisherman and the catch for each species, what was proposed by Castro-Mondragon et al. (2016) was used. Where the average number of days worked was estimated using the survey data divided by the number of fishers surveyed, and the catch per species was calculated using the average number of days a fisher works (taking into account the length of the season for each species), times the average number of dozens a fisher catches per day times, multiplied by the total of fishermen that make up the nine fishing cooperatives.

The information provided by the fishermen in the survey, was corroborated in the field (arrival sites and restaurants) and in joint trips by the research team and fishermen to the fishing sites. to verify their catches.

Results and Discussion

The present analysis included 1,184 specimens of mollusks caught by artisanal fisheries and identified 17 families (10 bivalves, 6 gastropods and one polyplacophore) and 24 species (13 bivalves, 10 gastropods and one polyplacophore) (Table 2). For the states of Chiapas and Oaxaca, Ríos-Jara et al. (2008) have reported 47 species considered to be of commercial interest or with potential use; among these species, 40 are reported for human consumption (31 bivalves and 9 gastropods), and the remaining species are for artisanal use. The difference in the number of species determined by this work with respect to that reported by Ríos-Jara et al. (2008) is related to the size of the area studied, given that Oaxaca and Chiapas together have a coastline of approximately 788 km and their sampling was carried out in 9 localities located within the littoral zone and 55 stations on the continental shelf of both states. In contrast, the coastal zone of the Costa Grande in Guerrero, which was the area studied, has an approximate extension of 260 km (Gutiérrez & Cabrera, 2012), and only those species that were caught by the fishing production cooperatives dedicated to mollusk fishing were inventoried. Of the species that were inventoried, we coincided in five with those reported by the aforementioned author, which are: S. prismatica, P. multicostata, Spondylus limbatus, M. ringens and H. radix.

Table 2 Families, species, and common name of marine mollusks caught by fishing cooperatives on the Costa Grande, Guerrero, Mexico. 2017.

| Family | Species | Common name |

CG | IX | RL | VG | MI | LP | BPB | CGG | BR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class Bivalvia | |||||||||||

| Pinnidae |

Pinna rugosa (G. B. Sowerby I, 1835) |

Callo de hacha | x | x | x | x | |||||

|

Atrina maura (G. B. Soweby I, 1835) |

Callo de hacha | x | |||||||||

| Veneridae |

Periglypta multicostata (G. B. Sowerby I, 1835) |

Almeja reina | x | ||||||||

|

Megapitaria squalida (G. B. Sowerby I, 1835) |

Almeja chocolata | x | |||||||||

| Chamidae |

Chama buddiana (C. B. Adams, 1852) |

Ostión catarro | x | ||||||||

|

Chama coralloides (Reeve, 1846) |

Caracol violeta | x | x | ||||||||

| Pteriidae |

Pinctada mazatlanica (Hanley, 1856) |

Madreperla | x | x | x | ||||||

| Spondylidae |

Spondylus limbatus (G. B. Sowerby II, 1847) |

Callo margarita | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Gryphaeidae |

Hyotissa hyotis (Linnaeus, 1758) |

Garra de león | x | x | |||||||

| Mytilidae |

Modiolus capax (Conrad, 1837) |

Mejillón | x | ||||||||

| Ostreidae |

Striostrea prismatica (Gray, 1825) |

Ostión de roca | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Arcidae |

Anadara formosa (G. B. Sowerby I, 1833) |

Pata de mula | x | ||||||||

| Psammobiidae |

Gari panamensis (Olsson, 1961) |

Almeja voladora | x | ||||||||

| Class Gastropoda | |||||||||||

| Muricidae |

Hexaplex princeps (Broderip, 1833) |

Caracol chino | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

|

Hexaplex radix (Gmelin, 1791) |

Caracol chino negro | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

|

Hexaplex regius (Swainson, 1821) |

Caracol chino rosa | x | x | x | |||||||

|

Neorapana muricata (Broderip, 1832) |

Caracol mamey | x | x | ||||||||

|

*Plicopurpura columellaris (Lamarck, 1816) |

Caracol de tinte | ||||||||||

| Calyptraeidae |

Trochita trochiformis (Born, 1778) |

Gorrito | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Strombidae |

Lobatus galeatus (Swainson, 1823) |

Caracol burro | x | x | |||||||

| Fasciolariidae |

Pustulatirus praestantior (Melvill, 1891) |

Caracol chireta | x | x | |||||||

| Tonnidae |

Malea ringens (Swainson, 1822) |

Caracol calavera | x | ||||||||

| Turbinellidae |

Vasum caestus (Broderip, 1833) |

Caracol madera | x | x | |||||||

| Class Polyplacophopra | |||||||||||

| Chitonidae |

*Chiton articulatus G.B. Sowerby I, 1832 |

Cucaracha de mar | |||||||||

| Total de especies capturadas por cooperativa | 2 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 13 | 14 | ||

CG = Cerro de Guamilulle, IX = Isla de Ixtapa, VG = Vicente Guerrero, RL = Rivereña Lagunillas, MI = Morros de Ixtapa, LP = Los Pulpos, BPB = Buzos y Pescadores La Barrita, CGG = Costa Grande de Guerrero, BR =Buen Rumbo.

* Species that are not commercialized, used mainly for self-consumption, (fishermen who do not belong to the region were registered catching these species).

For the Costa Chica region of the state of Guerrero, Galeana-Rebolledo et al. (2018), reported 27 species of mollusks that are caught by riverine fishing, notwithstanding that the number of species reported for the Costa Chica and Costa Grande regions is similar, only 18 species that are caught are similar between both regions. The species that are caught in Costa Chica and not recorded in Costa Grande are: Lobatus peruvianus, Triplofusus princeps, Chama equinata, Chama mexicana, Megapitaria aurantica, Donax puntactostratus, D.caelatus, D. kindermani and Chaetopeura lurida (Table 3).

Table 3 Comparative list by coastal region of the state of Guerrero, of species of marine mollusks caught by artisanal fishing, 2018.

| Family | Species | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class Gastropoda | CC | A | CG | |

| *Fissurella gemmata (Menke, 1847) | x | |||

| Fissurellidae | *Fissurella nigrocincta (Carpenter, 1856) | x | ||

| Fissurella rubropicta (Pilsbry, 1890) | x | |||

| Fissurella asperella (G. B. Sowerby I, 1835) | x | |||

| Lottiddae | Lottia fascicularis (Menke, 1851) | x | ||

| Turbinidae | Uvanilla unguis (W. Wood, 1828) | x | ||

| Neritidae | Nerita scabricosta (Lamarck, 1822) | x | ||

| Crucibulum scutellatum (Wood, 1828) | x | |||

| Calyptraeidae | *Crucibulum umbrella (Deshayes, 1830) | x | ||

| **Trochita trochiformis (Born, 1778) | x | |||

| Melongenidae | Melongena corona (Gmelin, 1791) | x | ||

| Conidae | Conus princeps (Linnaeus, 1758) | x | ||

| Conus brunneus (Wood, 1828) | x | |||

| Conus purpurascens (G. B. Sowerby I, 1833) | x | |||

| Strombidae | *Lobatus galeatus (Swainson, 1823) | x | x | x |

| Lobatus peruvianus (Swainson, 1823) | x | |||

| Strombus gracilior (G. B. Sowerby I, 1825) | x | |||

| Tonnidae | Malea ringens (Swainson, 1822) | x | x | x |

| Muricidae | Hexaplex erythrostomus (Swainson, 1831) | x | ||

| *Hexaplex regius (Swainson, 1831) | x | x | x | |

| *Hexaplex radix (Gmelin, 1791) | x | x | x | |

| *Hexaplex princeps (Broderip, 1833) | x | x | x | |

| *Neorapana muricata (Broderip, 1832) | x | x | x | |

| Acanthais triangularis (Blainville, 1832) | x | |||

| *Vasula speciosa (Valenciennes, 1832) | x | |||

| Stramonita biserialis (Blainville, 1832) | x | |||

| Plicopurpura Columellaris (Lamarck, 1816) | x | x | ||

| Fasciolariidae | *Triplofusus princeps (G. B. Sowerby, 1825) | x | ||

| *Leucozonia cerata (Wood, 1828) | x | |||

| *Polygona tumens (Carpenter, 1856) | x | |||

| *Opeatostoma pseudodon (Burrow, 1815) | x | |||

| Pustulatirus praestantior (Melvill, 1892) | x | x | ||

| Pustulatirus mediamericanus (Hertlein & Strong, 1951) | x | |||

| Vasidae | *Vasum caestus (Broderip, 1833) | x | x | x |

| Class Bivalvia | ||||

| Mytilidae | Mytella charruana (dˈOrbigny, 1842) | x | ||

| *Modiolux capax (Conrad, 1837) | x | x | x | |

| Arcidae | Anadara formosa (G. B. Sowerby I, 1833) | x | x | |

| Barbatia reeveana (d´Orbigny, 1846) | x | |||

| Pterridae | *Pinctada mazatlanica (Hanley, 1856) | x | x | x |

| Pteria sterna (Gould, 1851) | x | |||

| Pinnidae | Atrina maura (Sowerby, 1835) | x | x | x |

| *Pinna rugosa (G. B. Sowerby I, 1835) | x | x | x | |

| Ostreidae | Crassostrea columbiensis (Hanley, 1846) | x | ||

| Crassotrea corteziensis (Hertlein, 1951) | x | |||

| *Striostrea prismatica (Gray, 1825) | x | x | x | |

| Gryphaeidae | *Hyotissa hyotis (Linnaeus, 1758) | x | x | |

| Pectinidae | Nodipecten subnodosus (G. B. Sowerby I, 1835) | x | ||

| Spondylidae | Spondylus crassisquama (Lamarck, 1819) | x | ||

| *Spondylus limbatus (G. B. Sowerby II, 1847) | x | x | x | |

| Carditidae | Cardites crassicostatus (G. B. Sowerby I, 1825) | x | ||

| Cardites grayi (Dall, 1903) | x | |||

| Chamidae | *Chama coralloides (Reeve, 1846) | x | x | x |

| Chama echinata (Broderip, 1835) | x | x | ||

| Chama mexicana (Carpenter, 1857) | x | x | ||

| Chama sordida (Broderip, 1835) | x | |||

| *Chama buddiana (C. B. Adams, 1852) | x | x | ||

| Veneridae | Chionopsis amathusia (Philippi, 1844) | x | ||

| Megapitaria squalida (G. B. Sowerby I, 1835) | x | x | x | |

| Megapitaria aurantiaca (G. B. Sowerby I, 1831) | x | |||

| Periglypta multicostata (Sowerby, 1835) | x | x | x | |

| Donacidae | Donax kindermani (Philippi, 1847) | x | ||

| Donax caelatus (Carpenter, 1857) | x | |||

| Donax punctatostratus (Hanley, 1843) | x | |||

| Gari maxima (Deshayes, 1855) | x | |||

| Psammobiidae | Gari panamensis (Olsson, 1961) | x | x | x |

| Class Polyplacophora | ||||

| Chitonidae | *Chiton articulatus (Sowerby in Broderip & Sowerby, 1832) | x | x | x |

| Chaetopleuridae | Chaetopleura lurida (Sowerby, 1832) | x | ||

CC= Costa Chica, A= Acapulco, CG= Costa Grande

*Mollusk species that generate the highest economic income in the state of Guerrero, ** new species record for the state of Guerrero. Adapted from (Flores-Garza et al., 2012; Gutiérrez & Cabrera, 2012), Castro-Mondragon et al., 2015 and 2016; Galeana-Rebolledo et al., 2018).

In the region of Acapulco, Guerrero, Castro-Mondragon et al. (2016) reported 48 species that are caught by coastal fishing. Twice as many species are caught in this region as in Costa Grande. The capture of a greater number of species, is directly related to the demand for mollusks that comes from the City and Port of Acapulco de Juarez, given that it is a tourist and trade center of global importance and experiences a high demand for seafood for human consumption, which has led to an increase in fishing effort to meet market demand. The problem is that the mechanisms for regulating the fishing effort are scarce, which causes a depletion of commercially important populations, to the extent that some have ceased to be profitable and use has been made of other species that were not originally part of the coastal fishery to try to satisfy market demand and the personal income of the fishermen (Castro-Mondragon et al., 2015). This situation is not noticed in the Costa Grande region.

In the state of Guerrero, 66 species of marine mollusks have been reported, caught by coastal fishing (Flores-Garza et al., 2012; Gutiérrez & Cabrera et al., 2012; Torreblanca-Ramírez et al., 2014; Castro-Mondragon et al., 2016; Galeana-Rebolledo et al., 2018), of the species reported by this research, only T. trochiformis was recognized as a new record in the state of Guerrero, thus complementing the inventory of marine mollusk species caught by coastal fisheries to 67 species (Table 3).

The most important genus in the Costa Grande is Hexaplex, since three species of this genus were reported. For the states of Chiapas and Oaxaca, authors reported that the genus Anadara is the most important in the marine mollusk fishery (Ríos-Jara et al., 2008), since eight species of this genus are caught. For the Costa Chica and Acapulco, the genera Hexaplex and Chama have been reported with the highest number of species within commercial catches in the state (Flores-Garza et al., 2012; Gutiérrez & Cabrera et al., 2012; Castro-Mondragon et al., 2016; Galeana-Rebolledo et al., 2018). This research also recorded the genera Hexaplex (three species) and Chama (two species) as the most representative.

The species Striostrea prismatica and Hexaplex princeps were recorded as the main target of fishing by CFPS in the Costa Grande region. This trend was also reported for the Acapulco and Costa Chica regions (Castro-Mondragon et al., 2016; Galeana-Rebolledo et al., 2018), these species are distributed throughout the coastal zone of the state of Guerrero in depths ranging from 3 to 15 m, due to the fact that the main methods used in the coastal fishing of mollusks in the state are apnea diving and much less frequently semi-autonomous diving with the use of a compressor facilitates fishermen access to these species, in addition, the populations are relatively abundant and in the local market the demand is high and its commercial value is profitable, this represents good economic income for the fisherman and their families.

The species Chiton articulatus and Plicopurpura columellaris in the Costa Grande, were recorded as occasional fishing species and are mainly used for self-consumption by the fisherman and his family, however, it has been reported that C. articulatus in the other coastal regions of the state, is collected in large volumes and generates significant economic income (Galeana-Rebolledo et al., 2007; Olea- De la Cruz et al., 2013). During fieldwork, evidence was found of fishermen from the Acapulco region catching C. articulatus in Costa Grande, for transport and sale in Acapulco.

Regarding the species P. columellaris, it is protected by the Official Mexican Standard NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010, in Acapulco this species is reported in commercial catches and its meat is used for human consumption (Castro-Mondragon, et al., 2016). Table 2 shows the species of mollusks that are commercialized in different fishing cooperatives in Costa Grande.

The average number of days per week worked by each fisher is 5.4 days, which represents 259.2 days worked per year, this result is similar to what has been reported for the Acapulco and Costa Chica regions (Castro-Mondragon et al., 2016; Galeana-Rebolledo et al., 2018) and for the state of Guerrero by Gutiérrez & Cabrera (2012), who describe that fishing activity is carried out during most of the year, except for the months of greatest tropical disturbance, which are the months of rain and hurricanes, where fishing is practically suspended for safety reasons. According to the authors, in the first five months of the year the best catches can be obtained and in the following months these gradually decrease because of “bad weather”, but recover in the months of November and December.

Ten species were found to have the highest volumes of catch and these generate the highest economic income for fishermen (Table 4, Figures 2 and 3). This result is lower than that reported in Acapulco, (Castro-Mondragon et al., 2016), who recorded 16 species of marine mollusks, with the highest catch volumes by artisanal fisheries, four of these 16 species, were also reported in this research with the highest catch volumes: S. prismatica, H. princeps, N. muricata and H. hyotis. Eight species have a higher catch volume in Acapulco waters: Opeatostoma pseudodon (Burrow, 1815), Leucozonia cerata (Wood, 1828), Crucibullum umbrella (Deshayes, 1830) Fissurella nigrocincta (Carpenter, 1856), Polygona tumens (Carpenter, 1856), Vasula speciosa (Valenciennes, 1832), Fissurella gemmata (Menke, 1847) and Chiton articulatus (Sowerby in Broderip & Sowerby, 1832). In the case of the Costa Grande, fishermen do not focus their fishing effort on these species and some do not even catch them, because these species are not attractive for commercialization and do not generate economic income for the fishermen of the region.

Table 4 Total catch by season and economic contribution of the main species of mollusks that are fished by CFPS in Costa Grande, Guerrero.

| Species | Months of the fishing season |

Dozens caught | Price per dozen | Total revenue by species |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. prismatica | 9 | 102,527 | $150 | $15,379,050 |

| T. trochiformis | 9 | 82,482 | $80 | $6,598,560 |

| H. princeps | 12 | 40,760 | $180 | $7,336,800 |

| P. rugosa | 12 | 8,600 | $600 | $5,160,000 |

| S. limbatus | 12 | 18,040 | $250 | $4,510,000 |

| H. radix | 12 | 10,980 | $280 | $3,074,400 |

| C. buddiana | 12 | 8,400 | $100 | $840,000 |

| H. hyotis | 12 | 5,130 | $220 | $1,128,600 |

| H. regius | 12 | 2,490 | $280 | $697,200 |

| N. muricata | 12 | 1,080 | $180 | $194,400 |

a-a1) Chama buddiana; b-b1) Hyotissa hyotis; c-c1) Spondylus limbatus; d-d1) Pinna rugosa; e-e1) Striostrea prismatica.

Figure 2 Species of the Bivalvia Class that obtained the highest capture volumes and generated the highest economic income in Costa Grande, Guerrero.

a-a1) Hexaplex princeps; b-b1) Hexaplex radix; c-c1) Hexaplex regius; d-d1) Neorapana muricata; e-e1) Trochita trochiformis.

Figure 3 Species of the Gastropoda Class that obtained the highest capture volumes and generate the highest economic income in Costa Grande, Guerrero.

The observed difference in the type and number of commercially exploited species, between the two nearby regions, can be explained, as reported by Castro-Mondragon et al. (2016), by the fact that in Acapulco, there is a high demand for mollusks, mainly due to tourism and local consumption, to meet the demand, fishing effort is increased and species are diversified, in addition, other factors also influence, such as the lack of regulation and monitoring of fishing activity.

On the other hand, for the Costa Chica region (Galeana-Rebolledo et al., 2018), reported that five species are the most important in terms of catch volume: S. prismatica, H. princeps, H. radix, H. regius and L. galeatus. In the present research it was found that the first four species also contribute the highest catch volumes in Costa Grande. In the case of L. galeatus, Costa Grande fishermen, specifically those belonging to the municipality of La Unión reported that this species is bycatch, it is caught by scale fishing nets and its sale is through intermediaries that transport them to the municipality of Zihuatanejo. According to reports from interviewed CFPS members in Zihuatanejo, abundances of the species are low, because they were previously caught in large volumes to be transported to Acapulco for sale.

The survey with CFPS members showed evidence that at least five species have drastically reduced their populations: L. galeatus, M. ringens, P. multicostata, M. squalida and P. praestantior. The fishermen report that, due to the high price that these species command in the market, the fishing effort on these species has increased, which, added to the poor supervision by the authorities, led to a reduction in their populations and it is increasingly difficult to catch organisms of these species. The fishermen interviewed also reported that the clam populations of A. formosa and G. panamensis have decreased to such an extent that it is difficult to find them, so they have stopped directing their fishing effort towards these species.

Regarding the overexploitation and the changes in abundance that the populations of some mollusks have suffered, in the Costa Grande Baqueiro & Stuardo (1976), reported three species of clams D. ponderosa, M. aurantiaca and M. squalida as target species for fisheries in Zihuatanejo and Isla Ixtapa regions, which generated great economic income for fishermen almost 40 years ago. However, according to the results of the surveys applied to the fishermen, they mentioned that the first two species have completely disappeared from the catches, and in the case of the last species, M. squalida, the results showed a decrease in its populations, to such a degree that fishermen no longer focus their efforts on catching it.

From the total number of target species (10) in the Costa Grande, only two have a fishery management plan. S. prismatica has a period in which its capture is illegal from June 1 to August 31, established by Mexican law (CONAPESCA, 2015) and T. trochiformis has a period of fishing prohibition from June 1 to September 30, this prohibition was not enacted by the Mexican government, but was voluntarily adopted by fishermen with the purpose of protecting the species and making a rational use of this resource, since it occupies the second place in commercial importance in the region, this shows the importance of the CFPS in the process of catching and commercializing the mollusk resource and the fundamental role that these cooperatives could play in order to carry out fishing activities in a more sustainable manner in the Costa Grande region and in other areas such as Acapulco and Costa Chica where there is overexploitation.

Conclusion

This research concludes the first inventory of commercially important mollusk species that are caught by coastal fishing in the coasts of the state of Guerrero.

It was found that two genera of mollusks, Chama and Hexaplex, are the ones that contribute the most species to commercial catches in the state with five and three species, respectively.

In the Costa Grande, T. trochiformis represents the second largest catch and is only fished in this region, displacing Hexaplex to third place.

The species C. articulatus and P. columellaris, were recorded within the commercial catch in the Costa Grande region, these species do not generate income for the cooperatives, however, they are an essential part of the food for fishermen and their families.

This research found evidence of overexploitation of some species of mollusks such as Scutellastra mexicana (Broderip & GB Sowerby I, 1829), Megapitaria aurantiaca and Dosinia ponderosa, the fishing pressure suffered by the populations of these species was so high that they disappeared from the commercial catches in the region, of these species only S. mexicana has some kind of regulation, within the Official Mexican Standard (NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010), it is registered as an endangered species.

With respect to the above mentioned and according to the results of this research, the lack of regulation of the mollusk fishing activity and the disappearance of some species within the catches in the Costa Grande region of the state of Guerrero, for this reason it is proposed to carry out ecological-reproductive studies mainly of the species of commercial importance that are being subjected to greater fishing pressure, with the purpose of being able to determine aspects such as; reproductive cycles of the species, sizes of reproduction initiation and reproduction size, minimum catch sizes and fishing quotas, in order to regulate the fishing activity and allow local fishermen to also take actions with good practices oriented towards a responsible use of the resource.

REFERENCES

Baqueiro, E. & Stuardo, J. (1976). Observaciones sobre la biología, ecología y explotación de Megapitaria aurantiaca, (Sowerby., 1831), M. squalida (Sowerby., 1835) y Dosinia ponderosa (Gray, 1838) (Bivalvia: Veneridae) de la Bahía de Zihuatanejo e Isla Ixtapa, Gro., México. Anales del Centro de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, (4), 161-208. http://biblioweb.tic.unam.mx/cienciasdelmar/centro/1977-1/articulo29.html [ Links ]

Castro-Mondragon, H., Flores-Garza, R., Rosas-Acevedo, J. L., Flores-Rodríguez, P., García-Ibáñez, S. and Valdez-González, A. (2015). Escenario biológico pesquero y socio-económico de la pesca ribereña de moluscos en Acapulco. Revista Iberoamericana de Ciencias, 2 (7): 7-24. http://www.reibci.org/dic-15.html. [ Links ]

Castro-Mondragon, H., Flores-Garza, R., Valdez-González, A., Flores-Rodríguez, P., García-Ibáñez, S. and Rosas-Acevedo, J. L. (2016). Diversidad, especies de mayor importancia y composición de tallas de moluscos en la pesca ribereña en Acapulco, Guerrero, México. Acta Universitaria, 26 (6): 24-34. https://doi.org/10.15174/au.2016.1025 [ Links ]

Coan, E. V. & Valentich-Scott, S. P. (2012). Bivalve Seashells of Tropical West America. Marine Bivalve Mollusks from Baja California to Peru (1st. Ed.). Santa Barbara, California, USA. Everbest Printing Company through FCI Print Group. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256082346_Bivalve_seashells_of_tropical_west_America_Marine_bivalve_mollusks_from_Baja_California_to_Peru [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional de Acuacultura y Pesca [CONAPESCA]. (2015). Periodos y zonas de veda del ostión de piedra en el estado de Guerrero. Diario Oficial de la Federación. https://www.gob.mx/conapesca/prensa/actualiza-sagarpaperiodos-y-zonas-de-veda-del-ostion-de-piedra-en-el-estado-de-guerrero-20453 . [Last check: March 23th 2016]. [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional de Acuacultura y Pesca [CONAPESCA]. (2016). Dirección general de ordenamiento pesquero y acuícola, relación de títulos de pesca comercial para embarcaciones menores 2016. https://datos.gob.mx/busca/dataset/permisos-y-concesiones-de-pesca-comercial-para-embarcaciones-mayores-y-menores . [Last check: January 19th 2016] [ Links ]

Flores-Garza, R., García-Ibáñez, S., Flores-Rodríguez, P., Torreblanca-Ramírez, C., Galeana-Rebolledo, L., Valdés-González, A., Suástegui-Zárate, A. and Valdez-González, A. (2012). Commercially Important Marine Mollusks for Human Consumption in Acapulco, México. Natural Resources, 3(1): 11-17. https://dx.doi.org/10.4236/nr.2012.31003 [ Links ]

Galeana-Rebolledo, L., Suástegui-Herrera, M. A., Torales-Gutiérrez, G., Millán-Román, C. A., García-Ibáñez, S., Flores-Garza, R., Flores-Rodríguez, P. and Arana-Salvador, D. G. (2007). Estudio de la población del Chiton articulatus Sowerby, 1832 en Playa Ventura, Copala, Guerrero, como un recurso de importancia comercial. En: Estudios sobre la malacología y conquiliología en México. (E. Ríos-Jara, M. C. Esqueda-González, C. M. Galván-Villa, Eds.).. Guadalajara, México. Universidad de Guadalajara. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236173090_Estudios_sobre_la_Malacologia_y_Conquiliologia_en_Mexico [ Links ]

Galeana-Rebolledo, L., Flores-Garza, R., Violante-González, J., Flores-Rodríguez, P., García-Ibáñez, S., Landa-Jaime, V. and Valdés-González, A. (2018). Socioeconomic aspects for coastal mollusk commercial fishing in Costa Chica, Guerrero, México. Natural Resources, 9(6): 229-241. https://doi.org/10.4236/nr.2018.96015 [ Links ]

García, E. (1973). Modificaciones al Sistema de Clasificación Climática de Köppen (para adaptarlo a las condiciones de la República Mexicana). (2nd. ed.). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Geografía. https://books.google.com.mx/books?id=ko5dAAAAMAAJ&hl=es&source=gbs_book_other_versions. [ Links ]

García-Ibáñez, S., Flores-Garza, R., Flores-Rodríguez, P., Violante-González, J., Valdés-González, A. and Olea-de la Cruz, F. G. (2013). Diagnóstico pesquero de Chiton articulatus (Mollusca: POLYPLACOPHORA) en Acapulco, México. Revista de Biología Marina y Oceanografía, 48 (2): 293-302. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-19572013000200009 [ Links ]

Gorrostieta-Hurtado, E. y Trujillo-Toledo, J. L. (2012). Invertebrados marinos ribereños de importancia comercial en la costa michoacana. El BOHÍO Boletín, 2 (4): 17-29. https://www.yumpu.com/es/document/view/14635449/el-bohioboletin-vol2-no5-mayo-2012pdf-ciencia-y-biologia. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez, Z. R. M. & Cabrera, M. E. (2012). La pesca ribereña de Guerrero. Primera edición. Guerrero, México. Talleres de Ediciones de la Noche Madero, Guadalajara, México. https://inapesca.gob.mx/portal/documentos/publicaciones/LIBROS/librosdivulgacion/Pesca_de_Guerrero_web.pdf [ Links ]

Kaas, P., Van, Belle. R. and Strack, L. H. (2006). Monograph of living Chitons (Mollusca: POLYPLACOPHORA) Family Schizochitonidae. (6th. ed.). Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishers. https://brill.com/view/title/6790 [ Links ]

Keen, A. M. (1971). Sea shells of Tropical West America, (2nd. ed.). California, USA. Stanford University Press, Stanford. https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/1178437 [ Links ]

Morales-Pacheco, O., Gutiérrez-Zavala, R. M., Cabrera-Mancilla, E. and Gil-López, H. A. (2010). Dictamen para determinar la viabilidad técnica para la reasignación de permisos de pesca para la captura de escama marina en el litoral del estado de Guerrero. (Documento interno). Instituto Nacional de Pesca. [ Links ]

NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010. (Norma Oficial Mexicana). (2010). Protección ambiental-Especies nativas de México de flora y fauna silvestres-Categorías de riesgo y especificaciones para su inclusión, exclusión o cambio-Lista de especies en riesgo. Diario Oficial de la Federación. http://www.profepa.gob.mx/innovaportal/file/435/1/NOM_059_SEMARNAT_2010.pdf. [ Links ]

Olea-de la Cruz, F. G., García-Ibáñez, S., Flores-Garza, R., Flores-Rodríguez, P. and Rojas-Herrera, A. A. (2013). Pesca, oferta y demanda de la cucaracha de mar Chiton articulatus (Mollusca: polyplacophora) en aguas de la zona costera del estado de Guerrero, México. Ciencia Pesquera, 21 (1): 69-81. https://www.inapesca.gob.mx/portal/documentos/publicaciones/REVISTA/Mayo2013/Olea_et_al_2013.pdf [ Links ]

Ríos-Jara, E., Navarro-Caravantes, C. M., Sarmiento, N. N., Galván-Villa, C. M. and López-Uriarte, E. (2008). Bivalvos y gasterópodos (Mollusca) de importancia comercial y potencial de las costas de Chiapas y Oaxaca, México. Revista Ciencia y Mar, XII (35), 3-20. https://www.academia.edu/24072099/Bivalvos_y_gaster%C3%B3podos_Mollusca_de_importancia_comercial_y_potencial_de_las_costas_de_Chiapas_y_Oaxaca_M%C3%A9xico [ Links ]

Skoglund, C. (2002). “Panamic Province Molluscan Literature. Additions and Changes from 1971 through 2001, III GASTROPODA” 33 Supplement. California, USA. The Festivus. [ Links ]

Torreblanca-Ramírez, C., Flores-Garza, R., Flores-Rodríguez, P., García-Ibáñez, S., Michel-Morfín, J. E. and Rosas-Acevedo, J. L. (2014). Gasterópodos con potencial económico asociados al intermareal rocoso de la Región Marina Prioritaria 32, Guerrero, México. Revista de Biología Marina y Oceanografía, 49 (3): 547-557. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-19572014000300011 [ Links ]

Villegas-Maldonado, S., Neri-García, E., Flores-Garza, R., García-Ibáñez, S., Flores-Rodríguez, P. and Arana-Salvador, D. G. (2007). Datos preliminares de la diversidad de moluscos para el consumo humano que se expiden en Acapulco, Guerrero. En: Estudios sobre la malacología y conquiliología en México: (E. Ríos-Jara, M. C. Esqueda-González, C. M. Galván-Villa, Eds.). Guadalajara, México. Universidad de Guadalajara. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236173090_Estudios_sobre_la_Malacologia_y_Conquiliologia_en_Mexico [ Links ]

WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.marinespecies.org/photogallery.php?p=show&album=702&pg=72 . [Last check: January 21th 2019] [ Links ]

Cite this paper: Cerros Cornelio, J. C., Flores-Garza, R., Landa-Jaime, V., García-Ibáñez, S., Rosas-Guerrero, V., Flores-Rodríguez, P., Valdés-González, A. (2021). Species composition and income from coastal fishing mollusks on the Costa Grande of Guerrero Mexico. Revista Bio Ciencias 8, e1054. doi: https://doi.org/10.15741/revbio.08.e1054

Received: September 09, 2020; Accepted: March 21, 2021

texto en

texto en