Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

versión impresa ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.8 spe 19 Texcoco nov./dic. 2017

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v0i19.671

Articles

Scenarios of how climate change will modify the ‘Hass’ avocado producing areas in Michoacán

1Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias. Carretera Internacional México-Nogales km 6, Entrada a Santiago Ixcuintla, Nayarit. (alvarez.arturo@inifap.gob.mx).

2Campo Experimental Centro-Altos de Jalisco-INIFAP. Carretera libre Tepatitlán -Lagos de Moreno km 8, Tepatitlán, Jalisco, México. (ruiz.ariel@inifap.gob.mx).

3Campo Experimental Zacatecas-INIFAP. Carretera Zacatecas-Fresnillo km 24.5. Calera, Zacatecas, México. (medina.guillermo@inifap.gob.mx).

Since climate is a factor with strong influence on the phenology and physiology of crops, it is a priority to dimension the threat to climate change. There is evidence that such a change in the climate pattern will affect the production of fruit species such as avocado. To study the possible impact of climate change on the main producing region of avocado cv. Hass was the objective of the present work. Different climate databases were collected and were quantified changes of main meteorological variables when comparing the current climatology (1961-2010) and future scenarios, two paths representative concentration [RCP] of greenhouse gases (GEI) (4.5 and 8.5) for climatologies 2030, 2050 and 2070. This allowed to evaluate the impact in some phenological stages of the crop. The changes will be manifested with greater intensity towards the end of the century for the two RCP, with route 8.5 being the one that presents the most outstanding changes, particularly in temperature. This allowed us to identify the impact of climate change on the flowering stage in two climates (warm sub-humid and sub-humid), which will certainly affect the quantity and quality of fruit. The phenology of ‘Hass’ avocado cultivated in Michoacán is vulnerable to climate change due to two threats (increase of maximum temperature and delay of inflection of minimum temperature). The results point towards better future conditions for the cultivation of ‘Hass’ in the semi-warm sub-humid climate.

Keywords: Persea americana Mill.; ecophysiology; phenology; scenarios of climate change

Siendo el clima un factor con fuerte influencia sobre la fenología y fisiología de los cultivos, es prioritario dimensionar la amenaza ante el cambio climático. Existe evidencia que dicho cambio en el patrón climático afectará la producción de especies frutales como aguacate. Estudiar el posible impacto del cambio climático en la principal región productora de aguacate cv. Hass fue el objetivo del presente trabajo. Se acopiaron diferentes bases de datos climáticas y fueron cuantificados los cambios de las principales variables meteorológicas al comparar la climatología actual (1961-2010) y los escenarios futuros, en dos rutas de concentración representativas [RCP] de gases de efecto invernadero (GEI) (4.5 y 8.5) para las climatologías 2030, 2050 y 2070. Lo anterior permitió evaluar el impacto en algunas etapas fenológicas del cultivo. Los cambios se manifestarán con mayor intensidad hacia finales de siglo para las dos RCP, siendo la ruta 8.5 la que presenta los cambios más sobresalientes particularmente en temperatura. Lo cual permitió identificar el impacto que tendrá el cambio climático en la etapa de floración en dos climas (cálido subhúmedo y el semicálido subhúmedo) lo que seguramente afectará la cantidad y calidad de fruta. La fenología del aguacate ‘Hass’ cultivado en Michoacán es vulnerable al cambio climático por dos amenazas (aumento de la temperatura máxima y retraso de la inflexión de la temperatura mínima). Los resultados apuntan hacia mejores condiciones futuras para el cultivo de ‘Hass’ en el clima semicálido subhúmedo.

Palabras clave: Persea americana Mill.; ecofisiología; escenarios de cambio climático; fenología

Introduction

To assess if climate change will modify the avocado producing areas (Persea americana Mill.) Cv. Hass in Michoacán, it is necessary to identify and quantify the associated threat and vulnerability. Climate change is the variation of the climate with respect to historical average values. This variation must be quantified statistically and maintain its tendency for periods greater than 10 years. Among the causes of this variation are the change in land use and the increase in concentrations of greenhouse gases (GEI) in the atmosphere (IPCC, 2013).

The main cause of global warming is GEI concentrations since the industrial revolution in the 19th century, causing an increase in the average temperature of 0.8 °C to 2 °C in some regions of the world (Ring et al., 2012; Adedeji et al., 2014; Lane, 2015). In the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) the scientific community defined a set of four new scenarios to represent the presence of greenhouse gases as promoters of global climate change, called representative concentration trajectories (RCP) for its acronym in English.

The RCP are characterized by the approximate calculation of the total radiative forcing in the year 2100 in relation to the year 1 750, that is, 2.6 W m-2 in the case of the RCP2.6 scenario (low GEI emissions); 4.5 W m-2, in the case of scenario RCP4.5 and 6.0 W m-2, in scenario RCP6.0 (intermediate GEI emissions), and 8.5 W m-2, in the case of the RCP8 scenario which corresponds to high GEI emissions (IPCC, 2013). In Mexico the change in temperature and precipitation for the RCP4.5 scenario in the middle of the present century has been foreseen and rising to 2-3 °C and annual precipitation decreases of the order of 50 to 10 mm.

According to Hulme (1996), there are four ways in which climate would have a physical effect on crops: 1 distribution of agroecological zones; 2) higher photosynthetic rate; 3) less availability of water; and 4) agricultural losses or decreased yield. Hribar and Vidrih (2015), point out that increases in temperature and CO 2 concentrations will change fruit production by the end of the century. In Canada, for example, temperate fruit crops are expected to be affected mainly by less cold winters (Rochette et al., 2004). Similar results were found for walnut (Carya illinoinensis) in Sonora, Mexico, where decreasing winter cold hours have delayed flowering and decreased yield (Grageda et al., 2016). Despite the great ecological plasticity of the mango, it will face more extreme climatic conditions, mainly droughts and high temperatures (Sugiura et al., 2013).

Climate also has an effect on the external characteristics of the fruits of ‘Hass’ avocado (size, shape and roughness of the skin), in phytochemicals and oil (Salazar-García et al., 2011; Salazar-García et al., 2016a; Salazar-García et al., 2016b). For (Howden et al., 2005 and Puntland et al., 2011) the climate change can affect avocado production mainly because of its effect on temperature sensitive phenological stages, as floral differentiation, anthesis, mooring and fruit development. In some types of climate in Michoacán, Mexico, ‘Hass’ avocado presents up to three vegetative flows per year of different intensity (winter, spring and summer) that can result in three or four flowering periods (Rocha-Arroyo et al., 2011). An important stage in floral development is the irreversible determination of flowering (DIF), since it is the moment when the shoot buds change from the vegetative to the reproductive phase (Salazar-García et al., 1999). In Michoacán, the date of occurrence of DIF in winter shoots (giving rise to main flowering) of ‘Hass’ avocado occurs earlier in temperate than in warm (Rocha -Arroyo et al., 2010). After the DIF, floral development is carried out and Alvarez-Bravo and Salazar-García (2015) evaluated a model of floral development prediction for ‘Hass’ avocado in Michoacán (based on cold days accumulated at temperatures ≤16 °C) in shoots of the winter vegetative flow, which showed good predictive capacity (R2= 0.97).

The foregoing reveals the possible thermal threshold necessary for the climates of Michoacán, to have a floral development without setbacks. For Galindo- Tovar abd Arzate-Fernández (2010), avocado has had a long and fruitful adaptation to different climates, this evolution has conferred the capacity of resilience to adverse environments. However, in Michoacán is the main producing region of ‘Hass’ avocado in the world, so dimensioning the possible impact of climate change is of interest to producers, marketers, consumers, as well as to industry. For all of the above, the objective of this study is to identify how climate change will affect the distribution of the current ‘Hass’ avocado production area in Michoacán, Mexico

Materials and methods

Study zone

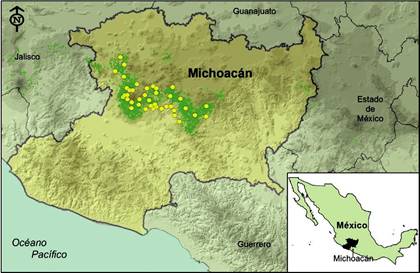

The avocado producing region in Michoacan concentrates 148 000 ha (72% of the national surface area). It is distributed mainly in four climates and 40 municipalities. Michoacan represents almost 80% of national production (1.5 million tons per year). The region presents contrasting climates and a phenological behavior of cv. Hass clearly differentiated (Rocha-Arroyo et al., 2011) (Figure 1).

Description of climates

In the producing region of ‘Hass’ in Michoacan at least 8 types of climate have been identified (García, 1964). For this study were selected the most widely distributed according to the percentage of established area of the crop. The most representative are sub-humid and subhumid temperate (89.21% of orchards) (Table 1).

Table 1 Characteristics of climates.

| Tipo de clima | Huertos (%) | Descripción climática |

| Cálido subhúmedo del tipo Aw1 | 1.08 | Temperatura media anual mayor de 22 ºC y temperatura del mes más frio mayor de 18 ºC. Precipitación del mes más seco menor de 60 mm; lluvias de verano con índice P/T entre 43.2 y 55.3 y porcentaje de lluvia invernal de 5% a 10.2% del total anual. |

| Semicálido subhúmedo (A)Ca(w1)+(A)Ca(w2) | 43.83 | Temperatura media anual mayor de 18 ºC, temperatura del mes más frio menor de 18 ºC, temperatura del mes más caliente mayor de 22 ºC. Precipitación del mes más seco menor de 40 mm; lluvias de verano con índice P/T mayor de 43.2 y porcentaje de lluvia invernal de 5% a 10.2% anual. |

| Templado subhúmedo del tipo Cb(w2) | 45.38 | Temperatura media anual entre 12ºC y 18ºC, temperatura del mes más frio entre -3 ºC y 18 ºC y temperatura del mes más caliente bajo 22 ºC. Precipitación en el mes más seco menor de 40 mm; lluvias de verano con índice P/T mayor de 55 y porcentaje de lluvia invernal de 5 a 10.2% del total anual. |

| Templado subhúmedo monzónico del tipo Cbm(w) | 6.47 | Temperatura media anual entre 12 ºC y 18 ºC, temperatura del mes más frio entre -3 ºC y 18 ºC y temperatura del mes más caliente bajo 22 ºC. Precipitación en el mes más seco menor de 40 mm; lluvias de verano y porcentaje de lluvia invernal de 5% a 10.2% del total anual. |

Selection of orchards Table 2

Table 2 Climate-selected orchards.

| Clima/Sitio | Latitud | Longitud | ASNM | Municipio | Localidad |

| Cálido subhúmedo (Aw1) | |||||

| 1 | 19° 18’ 50.1’’ | 101° 55’ 16.2’’ | 965 | Taretan | Taretan |

| 2 | 19° 13’ 02.5’’ | 101° 49’ 46.6’’ | 988 | Nuevo Urecho | El Calvario |

| 3 | 19° 18’ 47.4’’ | 101° 52’ 13.4’’ | 993 | Taretan | Hoyo del Aire |

| 4 | 19° 17’ 18.1’’ | 101° 58’ 40.1’’ | 1 001 | Uruapan | San Francisco |

| 5 | 19° 16’ 11.4’’ | 101° 50’ 09.1’’ | 1 016 | Taretan | Hoyo del Aire |

| 6 | 19° 17’ 21.2’’ | 102° 04’ 24.3’’ | 1 249 | Uruapan | Charapendo |

| 7 | 19° 19’ 06.9’’ | 102° 05’ 55.2’’ | 1 341 | Uruapan | San Francisco |

| 8 | 19° 17’ 08.8’’ | 102° 09’ 27.7’’ | 1 351 | Uruapan | Conejo |

| 9 | 19° 18’ 38.1’’ | 102° 02’ 24.8’’ | 1 555 | Uruapan | San Francisco |

| 10 | 19° 20’ 12.0’’ | 102° 03’ 08.8’’ | 1 601 | Uruapan | San Francisco |

| Semicálido subhúmedo (AcW1)+(AcW2) | |||||

| 1 | 19° 25’ 34.0’’ | 101° 52’ 45.0’’ | 1 549 | Ziracuaretiro | Ziracuaretiro |

| 2 | 19° 09’ 01.6’’ | 101° 46’ 31.9’’ | 1 582 | Ario de Rosales | Dr. Miguel Silva |

| 3 | 19° 12’ 08.9’’ | 101° 28’ 01.0’’ | 1 604 | Tacámbaro | Tacámbaro |

| 4 | 19° 41’ 48.0’’ | 102° 30’ 29.6’’ | 1 614 | Tocumbo | Tocumbo |

| 5 | 19° 38’ 18.0’’ | 102° 24’ 35.6’’ | 1 632 | Los Reyes | Atapan |

| 6 | 19° 19’ 54.5’’ | 102° 14’ 18.8’’ | 1 742 | Tancítaro | San José de la Peña |

| 7 | 19° 22’ 50.3’’ | 102° 07’ 12.2’’ | 1 863 | Nuevo Parangaricutiro | San Juan |

| 8 | 19° 30’ 46.4’’ | 102° 22’ 30.2’’ | 1 893 | Peribán | Peribán |

| 9 | 19° 17’ 40.3’’ | 102° 19’ 16.0’’ | 2 009 | Tancítaro | Zirimbo |

| 10 | 19° 24’ 50.7’’ | 102° 24’ 56.6’’ | 2 161 | Tancítaro | Tancítaro |

| Templado subhúmedo (Cw2) | |||||

| 1 | 19° 50’ 55.6’’ | 102° 26’ 54.9’’ | 2 069 | Tangamandapio | Tarecuato |

| 2 | 19° 23’ 51.2’’ | 101° 45’ 36.6’’ | 2 128 | Salvador Escalante | Turian Bajo |

| 3 | 19° 13’ 11.8’’ | 101° 35’ 45.8’’ | 2 136 | Ario de Rosales | El Tepamal |

| 4 | 19° 46’ 02.3’’ | 102° 24’ 17.6’’ | 2 202 | Los Reyes | Jesús Díaz |

| 5 | 19° 29’ 20.3’’ | 102° 20’ 31.8’’ | 2 241 | Peribán | Peribán |

| 6 | 19° 18’ 58.1’’ | 101° 27’ 54.1’’ | 2 244 | Tacámbaro | San José de los Laureles |

| 7 | 19° 31’ 32.2’’ | 101° 51’ 02.5’’ | 2 245 | Tingambato | Tingambato |

| 8 | 19° 17’ 32.5’’ | 101° 42’ 08.4’’ | 2 245 | Salvador Escalante | La Cantera |

| 9 | 19° 26’ 07.1’’ | 102° 23’ 50.6’’ | 2 290 | Tancítaro | Apo del Rosario |

| 10 | 19° 33’ 17.1’’ | 102° 15’ 34.8’’ | 2 379 | Nuevo Parangaricutiro | San Juan Viejo |

| Templado subhúmedo monzónico (Cm(w)) | |||||

| 1 | 19° 27’ 37.6’’ | 102° 02’ 20.9’’ | 2 194 | Uruapan | Uruapan |

| 2 | 19° 26’ 17.6’’ | 102° 10’ 00.5’’ | 2 208 | Nuevo Parangaricutiro | Rancha Nuevo |

| 3 | 19° 30’ 43.0’’ | 102° 08’ 40.3’’ | 2 214 | Uruapan | Las Cocinas |

| 4 | 19° 30’ 43.1’’ | 102° 02’ 10.5’’ | 2 215 | Uruapan | Zirapóndiro |

| 5 | 19° 31’ 56.8’’ | 102° 04’ 28.3’’ | 2 238 | Uruapan | Capacuaro |

| 6 | 19° 23’ 29.9 | 102° 22’ 06.1’’ | 2 436 | Tancítaro | El Jazmín |

| 7 | 19° 23’ 30.1’’ | 102° 13’ 45.4’’ | 2 485 | Nuevo Parangaricutiro | Las Amapolas |

| 8 | 19° 29’ 19.2’’ | 102° 18’ 32.0’’ | 2 497 | Uruapan | Nuevo Zirosto |

| 9 | 19° 21’ 30.9’’ | 102° 19’ 08.5’’ | 2 519 | Tancítaro | Zirimondiro |

Reference climatology (current)

The period 1961-2010 was used, for which the climate information system interpolated by INIFAP was used at a resolution of 90 m. The climatic variables obtained from the system were: annual mean minimum temperature (Tmin), mean annual maximum temperature (Tmax), mean annual temperature (Tmed) and annual cumulative precipitation (Pcp).

Climate change scenarios (futures)

We used the INIFAP climate change information system derived from the assembly of 11 general circulation models: BCC-CSM1-1, CCSM4, GISS-E2-R, HadGEM2-AO, HadGEM2-ES, IPSL-CM5A-LR, MIROC-ESM-CHEM, MIROC-ESM, MIROC5, MRI-CGCM3, NorESM1-M for RCPs 4.5 and 8.5 in three temporalities or future climatologies: 2030, 2050 and 2070 in order to characterize the short, medium and long term respectively. The climatic variables were the same ones that were obtained for the reference climatology.

Calculation of climatic variables

For each study site, the value of the climatic variables Tmin, Tmax, Tmed and Pcp were collected. With the Excel Version 14 spreadsheet (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) the mean values for all climate variables were generated by climate type (average of 10 observations).

Phenological schemes

From the diagrams published by Rocha-Arroyo et al. (2011) chronology was obtained by type of flowering (normal, marceña, surpassed and crazy) and the vegetative flow (winter, spring and summer) by type of climate.

Monthly weather

In order to support the interpretation of the phenological schemes, the minimum monthly temperature of the reference climatology and the climatic change scenarios were included. The monthly data were extracted from the same INIFAP climate information system. Using the Access Version 14 database manager (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) the values of the ten sites of each climate were averaged for each month, scenario and climatology.

Results and discussion

Current climatology

The warm subhumid climate (Aw1) presented the highest thermal indicators of the four climates. Temperatures subhumid (Cbw2 ) and temperate humid (Cbm(w) were the coldest with Tmín 8.9 °C. Rainfall varied due to the orography of the region. The areas with the lowest precipitation include climates Aw1 and Cm(w) y thehighest Pcp (1 428.6 mm) is the subhumid temperate climate (Table 3). This coincides with that mentioned by García (1964) for temperate climates (sub-humid and humid). However, for the warm climate the results were lower (0.3 °C), whereas for the semi-warm climate they surpassed in 1.1 °C the typical value of this climate. The differences found may be due to the data source used, as well as the reference climatology. The result of the analysis of the climatological variables of the present work agrees with the agroecological requirements for the production of ‘Hass’ published by Ruiz et al. (2013).

Future climate change scenarios

The behavior of climatic variables under an intermediate GEI emissions scenario (RCP 4.5) surpasses 2 °C increase by the end of the century in the four climates of the Hass avocado producing region in Michoacán. The most representative increase occurs in the Tmax and Tmed in the temperate sub-humid climate. In contrast, Pcp shows decrease in all horizons and climates, with mean values of -40 mm. The mid-century horizon (2050) stands out with a drop in precipitation from 3.56% in the subhumid temperate climate to 4.20% in the semi-humid sub-humid climate (Table 4).

Table 4 Climate simulation for RCP 4.5 in three different horizons by climate type.

| Climatología | T mín (°C) | T máx (°C) | T med (°C) | P (mm) | |||||||

| Simz | Dif y | Sim | Dif | Sim | Dif | Sim | Dif | ||||

| Cálido subhúmedo (Aw1) | |||||||||||

| Horizonte 2030 | 14.91 | 1.18 | 30.95 | 1.35 | 22.93 | 1.26 | 1 115 | -30 | |||

| Horizonte 2050 | 15.43 | 1.71 | 31.55 | 1.94 | 23.49 | 1.83 | 1 115 | -43 | |||

| Horizonte 2070 | 15.72 | 2 | 32.02 | 2.41 | 23.87 | 2.2 | 1 116 | -29 | |||

| Semicálido subhúmedo (A)Ca(w1)+(A)Ca(w2) | |||||||||||

| Horizonte 2030 | 12.58 | 1.19 | 28.16 | 1.36 | 20.37 | 1.27 | 1 186 | -36 | |||

| Horizonte 2050 | 13.11 | 1.72 | 28.76 | .97 | 20.94 | 1.84 | 1 171 | -51 | |||

| Horizonte 2070 | 13.41 | 2.02 | 29.21 | 2.41 | 21.31 | 2.22 | 1 178 | -45 | |||

| Templado subhúmedo C(w2) | |||||||||||

| Horizonte 2030 | 10.08 | 1.19 | 26.05 | 1.37 | 18.06 | 1.28 | 1 393 | -35 | |||

| Horizonte 2050 | 10.61 | 1.72 | 26.66 | 1.98 | 18.63 | 1.85 | 1 378 | -51 | |||

| Horizonte 2070 | 10.89 | 2.01 | 27.12 | 2.44 | 19.01 | 2.23 | 1 384 | -43 | |||

| Templado húmedo Cbm(w) | |||||||||||

| Horizonte 2030 | 10.04 | 1.19 | 24.65 | 1.37 | 17.35 | 1.28 | 1 164 | -34 | |||

| Horizonte 2050 | 10.57 | 1.72 | 25.25 | 1.98 | 17.91 | 1.85 | 1 149 | -50 | |||

| Horizonte 2070 | 10.88 | 2.03 | 25.7 | 2.42 | 18.29 | 2.23 | 1 156 | -43 | |||

z= datos de simulación para las climatologías; y= diferencia aritmética de restar el valor de un horizonte menos la climatología de referencia.

Climate change in a scenario of high GEI emissions (RCP 8.5) shows the greatest differences in reference climatology in all climates (1961-2010). Temperature increases of more than 3 °C, which highlights Tmax with 3.74 °C in the horizon 2070. The exchange rate between the middle and end of the century in all thermal variables is greater than 1 °C. As far as Pcp is concerned, all the climates and all horizons of the decrease, being the 2070 horizon where the decrease (less than 120 mm) is accentuated, which represents on average 10% of the Pcp in each of the four climates (Table 5).

Table 5 Climate simulation for RCP 8.5 in three different horizons by climate type.

| Climatología | T mín (°C) | T máx (°C) | T med (°C) | P (mm) | |||||||

| Simz | Dif y | Sim | Dif | Sim | Dif | Sim | Dif | ||||

| Cálido subhúmedo (Aw1) | |||||||||||

| Horizonte 2030 | 15.23 | 1.51 | 31.45 | 1.84 | 23.34 | 1.68 | 1 083 | -62 | |||

| Horizonte 2050 | 15.9 | 2.18 | 32.27 | 2.66 | 24.09 | 2.42 | 1 055 | -90 | |||

| Horizonte 2070 | 16.92 | 3.19 | 33.34 | 3.74 | 25.13 | 3.47 | 1 022 | -123 | |||

| Semicálido subhúmedo (A)Ca(w1)+(A)Ca(w2) | |||||||||||

| Horizonte 2030 | 12.93 | 1.54 | 28.65 | 1.85 | 20.79 | 1.69 | 1 158 | -64 | |||

| Horizonte 2050 | 13.62 | 2.23 | 29.47 | 2.67 | 21.54 | 2.45 | 1 130 | -92 | |||

| Horizonte 2070 | 14.63 | 3.24 | 30.54 | 3.74 | 22.58 | 3.49 | 1 085 | -137 | |||

| Templado subhúmedo Cb(w2) | |||||||||||

| Horizonte 2030 | 10.39 | 1.51 | 26.53 | 1.84 | 18.46 | 1.67 | 1 377 | -52 | |||

| Horizonte 2050 | 11.09 | 2.21 | 27.35 | 2.66 | 19.22 | 2.44 | 1 354 | -75 | |||

| Horizonte 2070 | 12.11 | 3.23 | 28.42 | 3.74 | 20.27 | 3.49 | 1 307 | -122 | |||

| Templado húmedo Cbm(w) | |||||||||||

| Horizonte 2030 | 10.42 | 1.57 | 25.12 | 1.84 | 17.77 | 1.7 | 1 143 | -55 | |||

| Horizonte 2050 | 11.08 | 2.23 | 25.94 | 2.66 | 18.51 | 2.45 | 1 119 | -80 | |||

| Horizonte 2070 | 12.11 | 3.26 | 27.01 | 3.73 | 19.56 | 3.49 | 1 069 | -129 | |||

z= datos de simulación para las climatologías; y= diferencia aritmética de restar el valor de un horizonte menos la climatología de referencia.

The increase in Tmin according to the scenarios RCP 4.5 and 8.5, would be beneficial to reduce the risk of exposure to low temperatures (<10 °C) which could affect the development of the crop, especially in the flowering phase (Whiley and Winston, 1987; Zamet, 1990). It is possible that such conditions occur in the four climates for the three horizons.

The increase in maximum temperature could represent a limiting factor for cv. Hass in Michoacán. The floral opening periods of ‘Hass’ are usually 40 to 90 days, with the periods being short for high temperatures during flowering. However, high temperatures (33 °C) during flowering not only shorten the period of flower opening, but also reduce the number of flowers that open (Sedgley and Annells, 1981) and decrease the viability of pollen. The short periods of flowering reduce the probability of harvesting of fruit and consecutively the production of fruit.

After the pollination and fertilization of the ovule the formation and development of the embryo begins. In cv. Hass initial embryo growth is also sensitive to high temperatures obtaining maximum initial growth at 25/20 °C (day / night) and death of embryos at temperatures 28 - 33 °C (Sedgley and Annells, 1981). The fruit fall (< 5 mm) in avocado is also caused by the maximum extreme temperatures (R2= 0.72), as well as the low relative humidity (R2= 0.87) associated with high temperatures (Lahav and Zamet, 1999). The conditions mentioned will only be presented in the warm sub-humid climate under the RCP 8.5 scenario in the 2070 horizon. However, increasing temperature in combination with a decrease in precipitation will increase crop stress (increased evapotranspiration), impact of temperature increase (Ruiz et al., 2011).

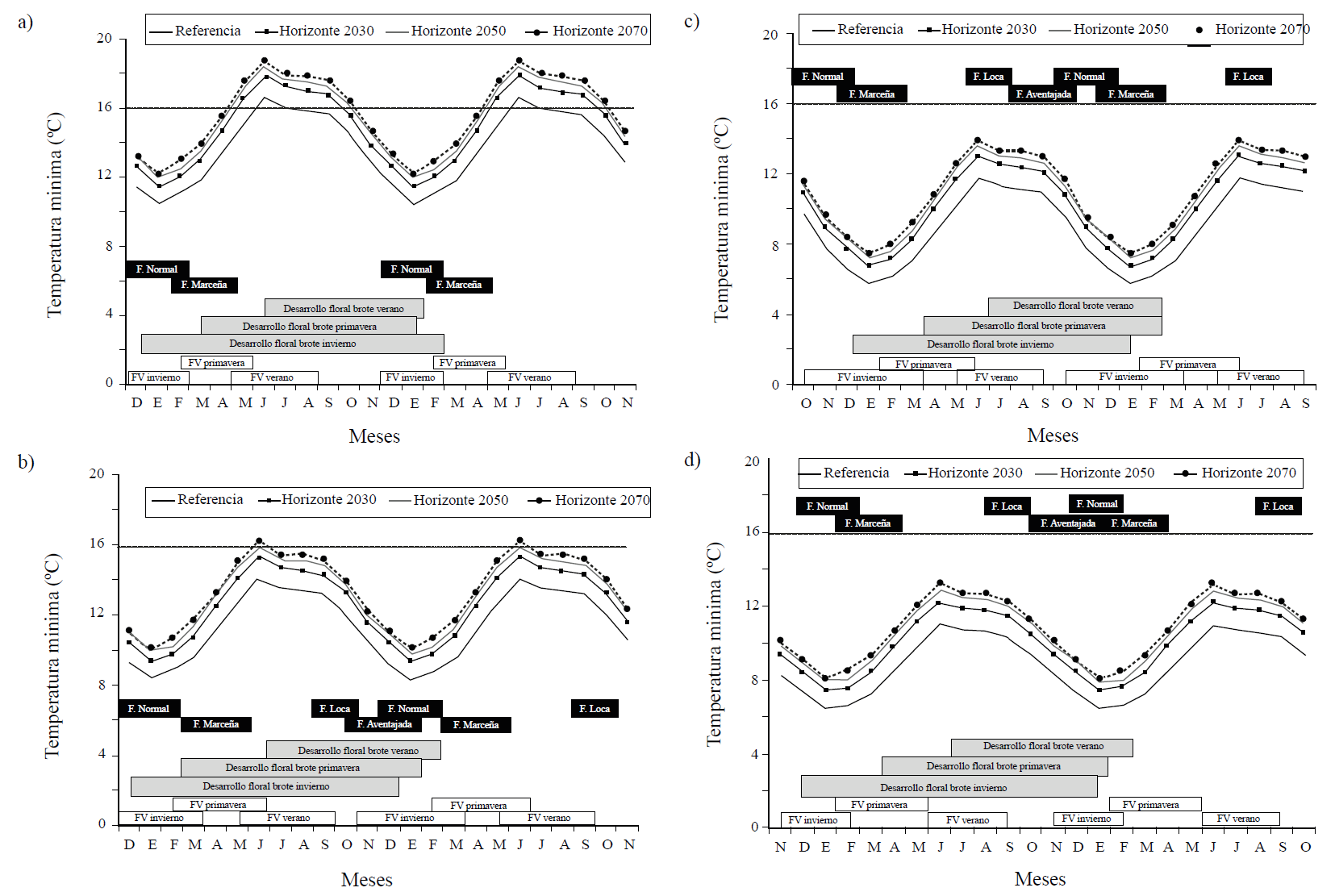

Thermal threshold for floral development

The climatic change only allows to affect the process of floral development in the climates of the producing region of avocado in Michoacán (warm subhumid and the semicalido subhumid). Temperate climates still remain below the critical threshold (Tmín ≤ 16 °C) (Álvarez-Bravo and Salazar-García, 2015). In the warm sub-humid climate in the three horizons of the intermediate stage in GEI emissions the Tmin exceeds the threshold for seven months (april - october) (Figure 2A). In the sub-humid semi-warm climate, the threshold of 16 °C in june will be exceeded by the end of the century horizon (Figure 2B).

Figure 2 Tmin monthly for RCP 4.5 in three horizons and ‘Hass’ avocado phenology in climates: a) warm subhumid Aw1; b) sub-humid sub-fluid (A)Ca(w1)+(A)Ca(w2); c) subhumid tempering Cb(w2); and d) subhumid monsoon tempering Cbm(w). “F” refers to flowering and “FV” to vegetative flow.

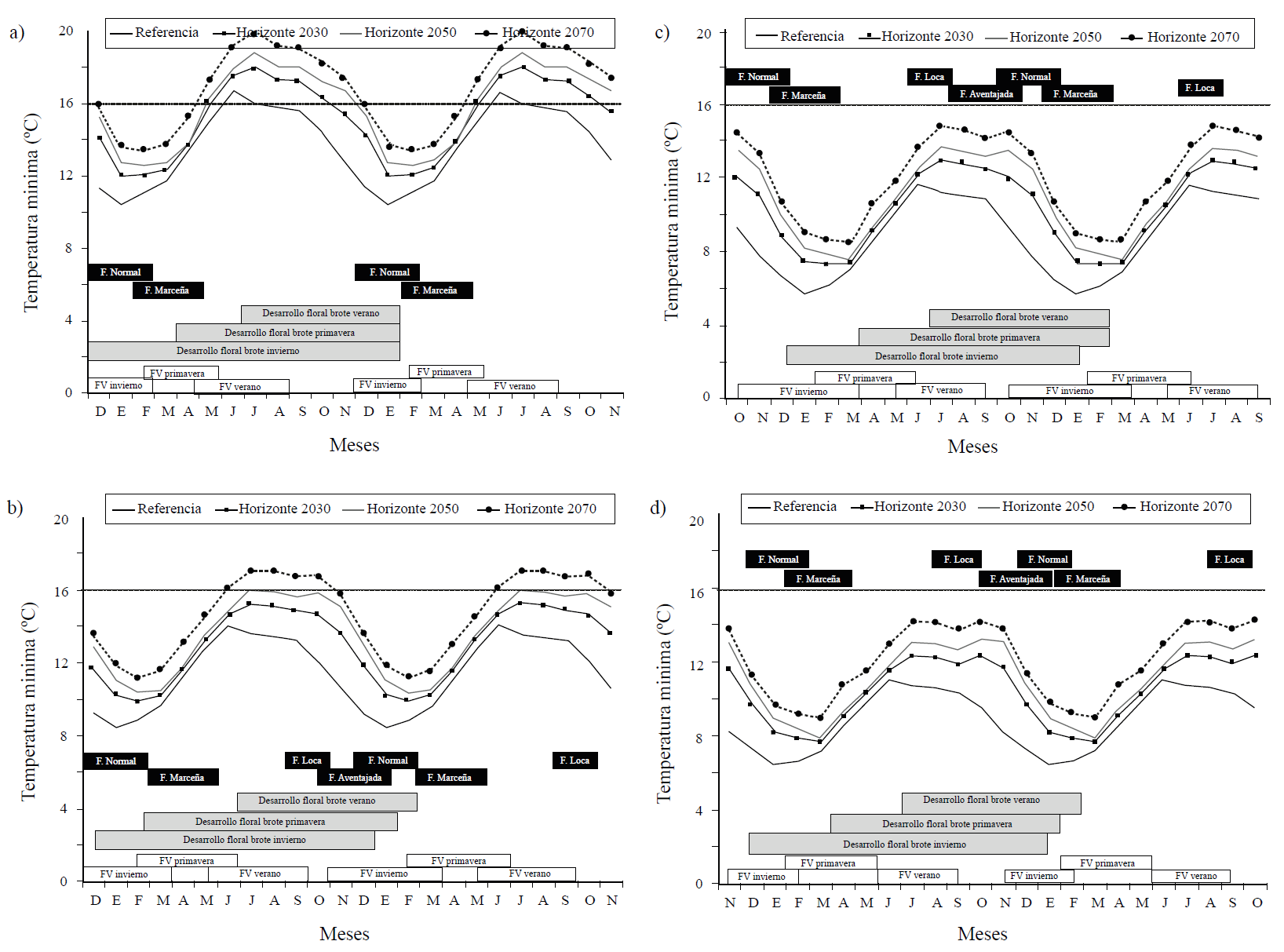

However, in the RCP 8.5 scenario not only increase the months of exposure to the critical threshold (april - december for the 2070 horizon) but also a Tmin of 20 °C in summer (Figure 2A). As far as the sub-humid semi-warm climate is concerned, it is only in the 2070 horizon that the line of 16 °C in the period june-october is expected to surpass (Figure 2B). This shows the vulnerability of cv. Hass report on climate change, coinciding with other studies concluding the negative impact of climate change on phenological stages sensitive to high temperatures (Howden et al., 2005; Putland et al., 2011).

This vulnerability of cv. Hass is recommended to be included in the future near a line of research aimed at the search of germplasm with the best adaptive response to high temperatures and its incorporation into genetic improvement programs, in order to obtain various best points to face the climate change of the present century.

Inflection of the minimum temperature

It is accepted that the transition from a warm period to a fresh one (decrease in minimum temperature) promotes the onset of floral development by inhibiting vegetative growth (Salazar-García et al., 2013). This inflection occurs in the four climates in the month of july in the reference climatology. However, in the average emissions scenario, there are increases in temperature in the three horizons but July prevails as the month of inflection (Figures 2A, 2B, 2C and 2D). While the monthly climatology in the high emissions scenario will have a negative impact on the four climates. In the warm and semi-humid sub-humid the inflection will move one month forward (august) (Figure 3A and 3B).

Figure 3 Tmin monthly for RCP 8.5 in three horizons and ‘Hass’ avocado phenology in climates: A) warm subhumid Aw1. B) sub-humid sub-fluid (A)Ca(w1)+(A)Ca(w2); C) subhumid tempering Cb(w2); and D) subhumid monsoon tempering Cbm(w). “F” refers to flowering and “FV” to vegetative flow.

While in the subhumid and subhumid temperate monsoon the inflection continues until two months later (september) (Figures 3C and 3D) with consequences in the possible disappearance of the marceña flowering. Rocha et al. (2010) indicated that the irreversible determination to flowering occurs earlier in temperate than in warm climates.

Considering the departure of the scenario RCP 8.5 that assertion will change in the horizon of mid and end of century. These changes in the climatic pattern will promote phenological alterations that will surely impact the quantity and quality of the fruit to be harvested, as shown by works carried out in Michoacán (Salazar-García et al ., 2011; Salazar-García et al., 2016a; Salazar-García et al., 2016b).

Conclusions

The phenology of ‘Hass’ avocado cultivated in Michoacán is vulnerable to climate change by two threats: 1. The increase of the average annual maximum temperature; and Delay of inflection (descent) of the minimum temperature. These impacts are regional and associated to climatic zones identified in this study. Therefore, climate change will change the production areas of this avocado cultivar. The zones with warm subhumid climate are most affected by the increase of the maximum temperature when exceeding the critical threshold of 33 °C, whereas in subhumid temperate climates and temperate subhumid monsoon, they will suffer the delay of floral initiation only for the trajectory of representative concentration (RCP) 8.5. The results point to better future conditions for ‘Hass’ cultivation in the semi-warm sub-humid climate (A)Ca(w1)+(A)Ca(w2),even with changes in future climate.

Literatura citada

Adedeji, O.; Reuben, O. and Olatoye, O. 2014. Global climate change. J. Geosci. Environ. Protection. 2(02):114. [ Links ]

Álvarez-Bravo, A. y Salazar-García, S. 2015. Validación de un modelo de predicción del desarrollo floral del aguacate ‹Hass› en Michoacán, México. In: VIII Congreso Mundial de la Palta. Lima, Perú. 380-385 pp. [ Links ]

Galindo, T. M. E. y Arzate, F. A. M. 2010. Consideraciones sobre el origen y primera dispersión del aguacate (Persea americana, Lauraceae). Cuadernos de Biodiversidad.(33):11-15. [ Links ]

García, E. 1964. Modificaciones al sistema de clasificación climática de Köppen. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). México, DF. México. Instituto de Geografía. Serie libros Núm. 6. 98 p. [ Links ]

Grageda, J. G.; Corral, J. A. R.; Romero, G. E. G.; Moreno, J. H. N.; Lagarda, J. V.; Álvarez, O. R. y Lagunes, A. J. 2016. Efecto del cambio climático en la acumulación de horas frío en la región nogalera de Hermosillo, Sonora. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc.(13) 2487-2495. [ Links ]

Howden, M.; Newett, S. and Deuter, P. 2005. Climate change-risks and opportunities for the avocado industry. In: proceedings of the New Zealand and Australian Avocado Grower’s Conference. Holland, P. (Eds.) Tauranga, New Zealand. 1-28. [ Links ]

Hribar, J. and Vidrih, R. 2015. Impacts of climate change on fruit physiology and quality. In: Proceedings. 50th Croatian and 10th International Symposium on Agriculture. Opatija. Croatia. 42- 45 p. [ Links ]

Hulme, M. 1996. Climate change and Southern Africa: an exploration of some potential impacts and implications for the SADC region. Norwich, UK: Climatic Research Unit, University of East Anglia. 1-104 pp. [ Links ]

IPCC. 2013. Resumen para responsables de políticas. En: Cambio Climático 2013: bases físicas. Contribución del grupo de trabajo I al quinto informe de evaluación del grupo intergubernamental de expertos sobre el cambio climático. Stocker, T. F.; Qin, D.; Plattner, G.-K.; Tignor, M.; Allen, S. K.; Boschung, J.; Nauels, A.; Xia, Y.; Bex, V. y Midgley. P. M. (Eds.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, Reino Unido y Nueva York, NY. Estados Unidos de América. 205 p. [ Links ]

Lahav, E. and Zamet, D. 1999. Flowers, fruitlets and fruit drop in avocado trees. Rev. Chapingo Ser. Hortic. 5: 95-100. [ Links ]

Lane, J. E. 2015. Global warming as evolution: rebuttal of two extreme positions. Open Access Library Journal. 2(10):1. [ Links ]

Putland, D.; Muller, J.; Deuter, P. and Newett, S. 2011. Potential implications of climate change and climate policies for the Australian avocado industry. Horticulture Australia. 1-116. [ Links ]

Ring, M. J.; Lindner, D.; Cross, E. F. and Schlesinger, M. E. 2012. Causes of the global warming observed since the 19th century. Atmospheric Climate Sci. 2(04):401. [ Links ]

Rocha-Arroyo, J. L.; Salazar-García, S. y Bárcenas-Ortega, A. E. 2010. Determinación irreversible a la floración del aguacate ‘Hass’ en Michoacán. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 1(4):469-478. [ Links ]

Rocha-Arroyo, J. L.; Salazar -García, S.; Bárcenas -Ortega, A. E.; González-Durán, I. J. y Cossio-Vargas, L. E. 2011. Fenología del aguacate ‘Hass’ en Michoacán. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 2(3):303-316. [ Links ]

Rochette, P.; Belanger, G.; Castonguay, Y.; Bootsma, A. and Mongrain, D. 2004. Climate change and winter damage to fruit trees in eastern Canada. Canadian J. Plant Sci. 84(4):1113-1125. [ Links ]

Ruiz, C. J. A.; Medina, G. G.; Ramírez, D. J. L.; Flores, L. H. E.; Ramírez, O. G.; Manríquez, O. J. D.; Zarazúa, V. P.; González, E. D. R.; Díaz, P. G. y Mora, O. C. 2011. Cambio climático y sus implicaciones en cinco zonas productoras de maíz en México. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. Pub. Esp. Núm. 2: 309-323. [ Links ]

Ruiz, C. J. A.; Medina, G. I. J.; González, A. H. E.; Flores, L. G.; Ramírez, O. C.; Ortiz, T. K. F. Byerly, M. y Martínez; P. R. A. 2013. Requerimientos agroecológicos de cultivos. Segunda edición. INIFAP. Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales Agrícolas y Pecuarias-CIRPAC-Campo Experimental Centro Altos de Jalisco. Tepatitlán de Morelos, Jalisco, México. Libro técnico Núm. 3. 564 p. [ Links ]

Salazar-García, S.; Garner, L. C. and Lovatt, C. J. 2013. Reproductive biology. In: Schaffer, B.; Wolstenholme, B. N. and Whiley, A. W. (Eds.). The avocado. 2nd (Ed.). Botany, Production and Uses. CABI, Oxfordshire, UK. 118-167 pp. [ Links ]

Salazar-García, S.; González-Durán, I. J. L. y Tapia-Vargas, L. M. 2011. Influencia del clima, humedad del suelo y época de floración sobre la biomasa y composición nutrimental de frutos de aguacate ‘Hass’ en Michoacán, México. Rev. Chapingo Ser. Hortic. 17(2):183-194. [ Links ]

Salazar-García, S.; Lord, E. M. and Lovatt, C. J. 1999. Inflorescence development of the ‘Hass’ avocado: commitment to flowering. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 124: 478-482. [ Links ]

Salazar-García, S.; Medina-Carrillo, R. E. y Álvarez-Bravo, A. 2016a. Influencia del riego y radiación solar sobre el contenido de fitoquímicos en la piel de frutos de aguacate ‘Hass’. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. Pub. Esp. Núm. 13: 2565-2575. [ Links ]

Salazar-García, S.; Medina-Carrillo, R. E. y Álvarez-Bravo, A. 2016b. Evaluación inicial de algunos aspectos de calidad del fruto de aguacate ‘Hass’ producido en tres regiones de México. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 7(2):277-289. [ Links ]

Sedgley, M. and Annells, C. M. 1981. Flowering and fruit-set response to temperature in the avocado cultivar ‘Hass’. Sci. Hortic. 14: 27-33. [ Links ]

Sugiura, T.; Ogawa, H.; Fukuda, N. and Moriguchi, T. 2013. Changes in the taste and textural attributes of apples in response to climate change. Scientific Reports, 3, 2418. [ Links ]

Whiley, A. W. and Winston, E. C. 1987. Effect of temperature at flowering on varietal productivity in some avocado-growing areas in Australia. Proc. First World Avocado Congress. South African Avocado Growers’ Association Yearbook. 10:45-47. [ Links ]

Zamet, D. N. 1990. The effect of minimum temperature on avocado yield. California Avocado Society Yearbook 74. USA. 247-256 pp. [ Links ]

Received: July 00, 2017; Accepted: September 00, 2017

texto en

texto en