Introduction

The purpose of the text is to analyze the border security policy agenda of the U.S. federal government under President Joe Biden. On the one hand, the policy of bilateral migration management has been managed through different mechanisms such as the Central America Development Plan, the North American Leaders Summit and the Bicentennial Initiative.

On the other hand, partisan actions have had an influence not only on citizen perceptions of immigration and immigrants, but have also led to an increase in detentions on the southern border of the United States and in Mexico-due to a much more active presence of different police forces-as well as an increase in irregular immigration situations of nationals from countries that traditionally did not form part of the people who tried to enter the United States by force, such as Haitians or Venezuelans.

One of the arguments for these changes refers to the fact that the agenda of President Joe Biden’s administration has raised a variety of security issues that are not necessarily linked to each other, which has made it difficult to reduce the determinants of irregular immigration and less drug trafficking to the United States. Therefore, the question of analysis that must be asked from the outset is: what is the impact and how has the border security agenda been managed? In particular, immigration in the first two years of President Joe Biden’s administration, without losing sight of the historical inertia that has sharpened the perception of the migration problem in recent years.

One of the premises proposed in this research is that the immigration agenda could be more relevant than the anti-drug or climate change agenda in U.S. policy, due to the greater importance of comprehensive migration management, compared to drug consumption or trafficking, in an electoral context. It should also be emphasized that partisan interest, and the dynamics of specific policies over the years, show that increases or decreases in migrant detention have much to do with immigration policies, and the neutralizing or permissive intent of a given administration (Melkonian-Hoover and Kellstedt, 2019: 53-55).

The increase in the number of detentions, except in special cases such as Haitians or Venezuelans, does not necessarily have to do with an increase in the flow of migrants. Firstly, because detainees normally attempt to cross several times; secondly, because the largest U.S. cities have for many years had large communities of Mexicans, Central Americans and Cubans settled there, and their transit has been a constant for many years; and thirdly, because the increase in police mobilization and the search and capture of migrants is what mainly explains the increase in detentions (Farris and Heather Silber, 2018: 817-819).

Immigration Policy and Management and the Multidimensional Context

The role of the U.S. Border Patrol has been central as a guarantor of security in land and sea borders, given the increase in various border problems, especially alcohol and arms trafficking, irregular immigration, trade, and drugs at the beginning of the 20th century (USGAO, 1999; McConnell, 2018). This multidimensional context has implied strengthening management of a policy of immigratory or customs control that has fallen under the purview of the Border Patrol, the Customs Service, and more recently the Customs and Border Protection Service (Jones, 2019). The central issue is the institutional capacity to effectively manage such an agenda, according to the priorities of U.S. domestic policy and the pressures of interest groups, which have evolved over the last eighty years.

At the dawn of the 20th century, the U.S. government proposed to strengthen regional security in the face of the growing negative impact from Mexican border populations, especially at the Baja California border (Jones, 2019). The federal government assigned responsibility to the then Border Patrol to enforce Section 8 of the Immigration Act of February 5, 1917 (39 Stat. 874: 8 USC), which prohibits smuggling, harboring, concealing, or aiding and trafficking of undocumented immigrants into the United States (Olson, 2018).

Initially the trend in the United States was to criminalize drug use, so in 1914 the Harrison Act came into force. This law prohibited the possession and consumption of drugs such as opiates, cocaine, and marijuana (Courtwright, 1995). During the first decades of the 20th century, the context of the then Northern District of the Federal Territory of Baja California was characterized by illegal trafficking of drugs and alcohol to the United States and limited cooperation between Mexico and the United States to combat these problems (Contreras, 2010). Since then and in the following decades, the border of southwestern Mexico and the state of California has been characterized by the promotion of a regional labor and drug market, which evolves with the increase in supply and demand (USGAO, 1999; Olson, 2018).

During World War II, the Border Patrol strengthened control over the border to prevent the entry of enemy spies, as well as the management of access for Mexican migrants through the Bracero Program (1942-1964). In this way, the Border Patrol strengthened its agenda: control of contraband goods such as alcohol and the first major management of regular labor mobility to the United States. Thus, for the first time, the institutional, legal, and administrative challenge of managing a complex comprehensive agenda in the context of a war situation was proposed, from a regional security perspective. Such management involved achieving a balance in the institutional agenda, considering the diversity of problems in a context of external risks and threats with implications on the Mexico-United States border. This multidimensional agenda over the years has been strengthened, especially in the context of the emergence and development of drug trafficking to the United States in the post-war period (Ramos, 1995). The post-war period caused the United States to emerge as a power with a regional security perspective, for which border protection was strategic (Slack, et al., 2016).

During the 1980s and 1990s, there was a significant increase in illegal migration to the United States in the context of the growing U.S. economy (Council on Foreign Relations, 2009). It was in this context that the first immigration reform was proposed during the government of Republican President Ronald Reagan, called the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA), on November 6, 1986. The aim of this law was to regulate irregular immigration to the United States (Fitzgerald, 2016).

At the beginning of the 1990s (January 1, 1994), the process of commercial integration was institutionalized through the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). The U.S. border security policy strengthened its commercial agenda with the aim of preventing drug trafficking from Mexico in the context of the opening of borders (Ramos, 1995; Brown, 2017). This is in addition to the increasing labor mobility from Mexico and Central American countries. The growth of the U.S. economy is the main incentive for irregular labor mobility, which has led to institutional responses for greater border control (Council on Foreign Relations, 2009).

The role of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in the United States has been strengthened in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and post-pandemic with a diverse agenda of problems (security, terrorism, drug control, and irregular and regular immigrants). DHS is the agency responsible for border security and border protection (land, sea and airports) and its role is prevention and response at the U.S. borders.

The main functions of the DHS include protecting the borders from the illegal movement of weapons, drugs, contraband, and people; and it is also responsible for legal trade and travel (CBP, 2022). Thus, its main function is to strengthen national security policies, economic prosperity and national sovereignty. DHS also promotes economic security in terms of regulating the uninterrupted flow of goods and services, people and capital, and information and technology across borders. Through U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)-under which U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) operates-these agencies are charged with protecting the country from cross-border crime and illegal immigration. The DHS was created in the aftermath of the 2001 terrorist attacks. The DHS has managed the terrorist agenda and in doing so has promoted various institutional mechanisms to promote border security without affecting border crossings of people, cars and trade. In this context, the 21st Century Border program was created, which aims to control borders without reducing border crossings based on the use and development of technology (Chaar-López, 2019).

The diversity of DHS functions means that border security policy and management is challenged to reconcile the risk agenda and in particular border control; immigration and drug trafficking versus an agenda associated with the right to migrate, asylum options, respect for human rights and development options to reduce migration flows (Biden, 2020a; 2020b). The difficulty of devising such a balance has been a source of tension in U.S. border security policy and management over the past 22 years.

The pandemic framework (March 2020-2022) implied a further strengthening of the role of DHS and particularly CBP in managing the control of migration flows in a pandemic context-the implementation of the criteria established by Title 42 (Park and Conway, 2020). These two institutional frameworks imply a challenge for U.S. immigration policy and management to adopt a comprehensive approach to managing the changes in migration patterns at the southern border over the last decade, according to the needs of border control and the demands for asylum, development alternatives, employment and immigration regularization and family reunification (Cardinal, 2022). This comprehensive concept of migration management and policy is associated with the conceptual and institutional difficulty of merging immigration enforcement with policies to control drugs, terrorism, and other security threats.

The institutional capacity of U.S. immigration policy and management implies addressing the risks and threats of both migratory flows and organized crime from Central America and Mexico, and proposing an agenda based on security and development in the region, in line with the priorities agreed in the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (Biden, 2020a; 2020b). With this, the policy raises the importance of considering the new dimensions of migratory flows and asylum demands; and, on the other hand, the management and border control policy for both immigrants and drugs. This institutional development implies changes in migration management, as well as better management of crime, drugs, smuggling and terrorism, and economic investment in the region. All of these issues are part of the U.S.-Mexico security and development agenda. Therefore, to better manage migration with a comprehensive approach, it is essential to redesign the border infrastructure and the asylum system (Cardinal, 2022). Effective management of the dimensions of border security: personnel, technology and infrastructure with a better institutionalization, rights-based approach and development is a priority for security and immigration policy in the United States.

This comprehensive approach to migration policy and management in the United States has not been a priority of the public agenda due to the institutional interest in emphasizing the control of irregular immigration and drug flows across the southern border, rather than improving asylum management and the implementation of a development policy in the Northern Triangle countries and Mexico.

The conceptual implications of the role and impacts of the United States border security policy over the last eighty years reflect the following challenges:

a) the diversity of a multidimensional agenda on border security, which is articulated with a national security and development agenda in the United States (Stein, 2020);

b) U.S. immigration bureaucratic policy impacts other domestic, international, and transborder policy agendas and therefore impacts transborder cooperation mechanisms (Hess, 2020);

c) the federal border security agenda impacts regional and local migration governance processes in both the United States and Mexico (Márquez and Delgado, 2018);

d) U.S. immigration containment policies have had effects on regional and international mobility but have not totally reduced such flows;

e) the differences in border security policies in the Clinton, Bush, Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations reflect the complexity of managing multilevel and multi-actor agendas in security, labor mobility, labor demand, rights, health, and vulnerability (Pew Research Center, 2022);

f) the immediate future of a U.S. agenda for orderly, safe, and humane migration management involves integrating normative, labor, rights, inclusion, gender, and cooperation frameworks (O’Rourke, 2021).

Trends in Mexico-United States-Central America Migration Flows, 2001-2022

As shown in Table 1 and Table 2, coexistence and documented crossings between the United States and Mexico, on the one hand, and between Guatemala, Belize and Mexico, on the other, are normal and regular.1 Mexico’s northern border with the United States consists of eight regular points between the state of Baja California and California; seven between Sonora and Arizona; nine with Texas and Chihuahua, three in Coahuila, one in Nuevo León, and thirteen in Tamaulipas. Between 2017 and August 2022-despite the pandemic, which reduced the flow but did not interrupt the passage; nor did it close the borders-17,260,031 people entered Mexico in a documented manner. Of these, 59.5 percent passed through California, 36.9 percent through Texas, and the remaining 3.6 percent through Arizona.

Table 1 Documented entries through the different border points of the northern border of Mexico (2017-2022)

| State | Municipality | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

| Baja California | Algodones | 3,162 | 3,895 | 3,113 | 2,299 | 2,234 | 1,402 |

| Mexicali I | 29,705 | 35,611 | 47,239 | 28,646 | 45,534 | 16,475 | |

| Mexicali II | 20,472 | 25,109 | 24,011 | 13,433 | 15,682 | 10,506 | |

| Tecate | 18,469 | 17,695 | 17,778 | 6,829 | 10,882 | 9,842 | |

| Tijuana, Chaparral 1 | 235,621 | 494,283 | 314,880 | 200,346 | 162,369 | 121,184 | |

| Tijuana, Mesa de Otay | 106,069 | 134,819 | 128,393 | 92,170 | 46,751 | 22,141 | |

| Tijuana, Puerta México | 468,811 | 319,345 | 331,218 | 178,815 | 113,927 | 47,228 | |

| Tijuana-San Diego | 799,981 | 902,700 | 1,221,193 | 787,304 | 1,334,183 | 1,213,125 | |

| Sonora | Agua Prieta | 9,399 | 9,463 | 7,994 | 5,335 | 7,406 | 4,541 |

| Naco | 762 | 640 | 601 | 207 | 219 | 163 | |

| Nogales Tres | 5,329 | 4,660 | 4,337 | 1,422 | 684 | 151 | |

| Nogales Uno 9 | 85,522 | 81,556 | 79,732 | 55,347 | 79,577 | 38,802 | |

| San Luis Río Colorado | 5,360 | 5,660 | 5,937 | 3,158 | 5,511 | 3,475 | |

| San Luis Río Colorado II | 30,660 | 29,077 | 9,969 | 7,147 | 0 | 8,718 | |

| Sonoyta 10 | 4,465 | 5,193 | 5,480 | 4,127 | 4,908 | 3,333 | |

| Chihuahua | Cd. Juárez, Córdova | 58,636 | 63,614 | 73,773 | 27,795 | 68,271 | 57,556 |

| Cd. Juárez, Jerónimo | 82,117 | 86,570 | 86,044 | 59,024 | 90,214 | 53,280 | |

| Cd. Juárez, Libertad (Paso del Norte) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 953 | 207 | 0 | |

| Cd. Juárez, Reforma | 26,250 | 21,901 | 39,180 | 16,080 | 14,204 | 10,717 | |

| Cd. Juárez, Zaragoza 3 | 85,401 | 87,555 | 87,465 | 52,056 | 87,934 | 54,331 | |

| El Berrendo | 531 | 53,991 | 865 | 277 | 87 | 628 | |

| Gral. Rodrigo M. Quevedo, Puerto Palomas | 11,128 | 11,631 | 13,471 | 10,890 | 14,740 | 8,641 | |

| Guadalupe-Tornillo 4 | 68 | 47 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ojinaga | 64,474 | 71,887 | 81,514 | 57,485 | 87,753 | 55,029 | |

| Coahuila | Boquillas del Carmen | 6,467 | 3,984 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cd. Acuña | 14,027 | 15,072 | 16,961 | 10,256 | 17,873 | 9,710 | |

| Piedras Negras II 5 | 74,989 | 83,581 | 94,690 | 79,075 | 134,408 | 77,451 | |

| Nuevo León | Colombia, Puente Solidaridad | 24,032 | 26,355 | 25,295 | 19,059 | 28,407 | 12,992 |

| Tamaulipas | Camargo | 3,476 | 4,471 | 4,949 | 3,334 | 4,434 | 2,587 |

| Capote, Puente tlc | 45,642 | 44,843 | 43,785 | 24,041 | 39,172 | 25,131 | |

| Chalán “El Vado”, Díaz Ordaz | 45 | 58 | 80 | 13 | 0 | 0 | |

| Guerrero, Presa Falcón | 6,144 | 6,584 | 7,083 | 5,421 | 8,015 | 4,469 | |

| Matamoros, Zaragoza (Matamoros III) | 14,989 | 16,987 | 19,435 | 11,048 | 18,482 | 10,258 | |

| Miguel Alemán | 16,879 | 17,103 | 17,391 | 9,583 | 12,869 | 7,498 | |

| Nuevo Laredo I “Miguel Alemán” | 32,285 | 30,833 | 38,057 | 10,558 | 5,436 | 5,766 | |

| Nuevo Laredo II “Juárez-Lincoln” 11 | 487,420 | 480,537 | 466,160 | 217,401 | 264,640 | 160,690 | |

| Nuevo Progreso-Las Flores | 10,849 | 11,270 | 12,214 | 7,616 | 13,949 | 8,305 | |

| Puerta México (Matamoros II) | 37,629 | 41,821 | 65,115 | 43,308 | 41,129 | 30,326 | |

| Reynosa-Hidalgo, Benito Juárez I y II 12 | 50,446 | 52,457 | 55,204 | 38,060 | 54,578 | 35,808 | |

| Reynosa III-Pharr (Nuevo Amanecer) | 15,662 | 15,277 | 14,961 | 6,359 | 9,668 | 6,679 | |

| Reynosa Puente Anzaldúas-Mc Allen | 67,479 | 75,238 | 80,968 | 49,997 | 73,533 | 54,175 | |

| Total | 3,060,852 | 3,393,373 | 3,546,547 | 2,146,276 | 2,919,870 | 2,193,113 |

Source: Own elaboration based on “Monthly Statistical Bulletin” of the Migration Policy Unit of the National Institute of Migration (Instituto Nacional de Migración). The year 2002 includes data through August.

Table 2 Documented entries through southern border points of Mexico (2017-2022)

| State | Municipality | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chiapas | Frontera Ciudad Hidalgo/ Ciudad Tecún Uman | 833,940 | 705,081 | 491,385 | 371,961 | 475,160 | 238,939 |

| Frontera Talismán /El Carmen | 1,219,456 | 1,209,409 | 980,096 | 472,635 | 892,987 | 602,907 | |

| Frontera Ciudad Cuauthémoc/ La Mesilla | 60,959 | 70,662 | 104,017 | 37,856 | 53,328 | 22,255 | |

| Frontera Carmen Xhan / Gracias a Dios | 8,814 | 8,388 | 11,598 | 8,901 | 17,040 | 123,251 | |

| Frontera Corozal/Bethel- La Técnica | 3,752 | 3,305 | 2,683 | 984 | 898 | 868 | |

| Tabasco | El Ceibo/El Naranjo* | 35,976 | 37,419 | 31,535 | 10,610 | 22,192 | 18,320 |

| Quintana Roo | La Unión/ Blue Creek | 9,863 | 10,044 | 15,221 | 2,434 | 0 | 0 |

| Subteniente López/ Santa Elena | 510,723 | 493,759 | 565,724 | 107,380 | 14,613 | 259,805 |

* The case of the border crossing at El Ceibo (Tabasco) and Frontera Corozal (near Palenque in Chiapas) is interesting because it is a very important crossing point for undocumented migrants coming especially from Honduras, via the Guatemalan Petén. On October 27, 2009, Mexico opened a new, modern immigration station at the El Ceibo border crossing point, 50 kilometers from Tenosique (Tabasco), and shortly afterwards the number of documented visitors passing through this point increased.

Source: “Monthly Statistical Bulletin” of the Migration Policy Unit, Instituto Nacional de Migración (2017-2022). The year 2022 runs through August.

Mexico’s southern border with Guatemala and Belize has eight formal documentation points. Between 2006 and 2016, there were 21,750,573 documented crossings; and between 2017 and August 2022, there were 11,179,133 crossings. Of the border points, the ones that border Guatemala are five in the state of Chiapas and one in Tabasco. The two in Quintana Roo are with Belize.2

Apprehensions of undocumented migrants illustrate increases or decreases in their passage. However, the data is misleading, because much depends on the institutional political will of countries to proceed with a more intense apprehension campaign or a more permissive one. On the other hand, the political use of this information can confuse and alarm the receiving society or allow it to live barely perceiving the phenomenon, as has happened over several decades.

The case of Mexico, and the detentions of undocumented Central American and Cuban migrants who have traditionally crossed the country on their way to the United States, clearly confirms this affirmation. Between 2001 and August 2022, Mexico has detained 2,574,834 Central Americans and Cubans (Burgueño Angulo, 2021).

In the first stage, which could be described as the “inertia of Plan South” (2001-2007), as a result of the attack on the Twin Towers and a high flow of detainees by the U.S. Border Patrol on its southern border, Mexico detained 1,127,812 members of these communities, which represents 43.8 percent of the entire period (Castillo Ramírez, 2022).

A second stage (2008-2013), marked by the outbreak of the debate in Mexico on the concept of human rights, the appearance of the first migrants kidnapped and murdered by organized crime, and marked by the drafting of the Migration Law (2011) and its regulations (2013), only 367,362 (14.2 percent) were detained (Torre-Cantalapiedra and Yee-Quintero, 2018).

The third stage (2014-2018) represents a more aggressive approach toward the apprehension of migrants, following the dynamics of the Southern Border Plan, promoted by President Obama. At this point there was an increase in apprehensions to 626,280 (24.3 percent) (Fouillioux Bambach, 2020).

The last period, during the administration of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (2019-August 2022), was marked by the threats of President Trump toward Mexico, after the emergence of the migrant caravans at the end of 20183 (Hernández López and Porraz Gómez, 2020), the neutralization of migrants from this group also had a very high trend, with 453,380 people (17.6 percent) from this group of migrants being retained in a very short time, and in the middle of the process of the covid-19 pandemic.4

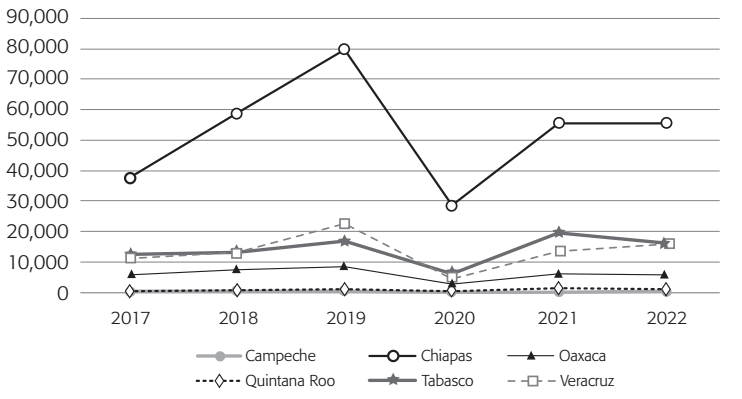

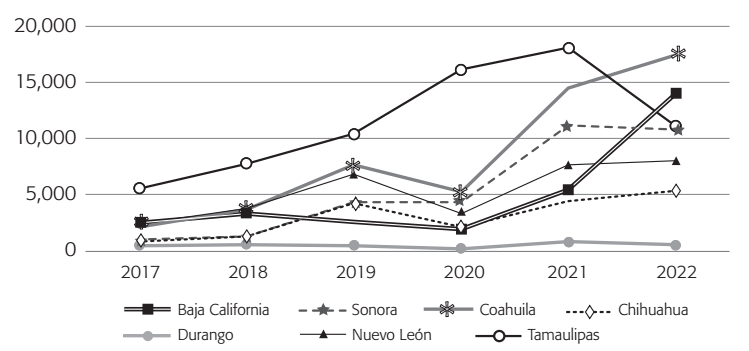

Mexico detained 858,330 undocumented migrants between 2017 and August 2022. Of these, 523,910 were detained in the states of Chiapas (60 percent), Tabasco (16 percent), Veracruz (16 percent), Oaxaca (7 percent) and Quintana Roo (1 percent).5 On its northern border, Mexico “rescued”6 236,357 undocumented migrants in the same period. Twenty-nine percent in Tamaulipas, 21 percent in Coahuila, 14 percent in Sonora and Nuevo León, 13 percent in Baja California, 8 percent in Chihuahua and 1 percent in Durango.

The analysis of the evolution of Mexican apprehensions over the years is relevant, as shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2 in real numbers. The year 2019, and especially 2021, and 2022 until August, are the years with the highest number of “rescues.” On the southern border, Chiapas, Tabasco and Veracruz are the states with the highest number of apprehensions over time.7 On the northern border, Tamaulipas is the state that detained the highest number of migrants, but Coahuila has a very significant increase in 2021 and 2022; as does Baja California, and in smaller numbers, but following the trend, the same happens in Sonora, Nuevo León and Chihuahua.8

Source: Own elaboration “Monthly Statistical Bulletin” of the Migration Policy Unit of the Instituto Nacional de Migración (2017-2022). The year 2002 is counted through August.

Figure 1 Prehensions at Mexico’s southern border (2017-2022)

Source: Own elaboration “Monthly Statistical Bulletin” of the Migration Policy Unit of the Instituto Nacional de Migración (2017-2022). The year 2002 is counted through August.

Figure 2 Apprehensions at Mexico’s northern border (2017-2022)

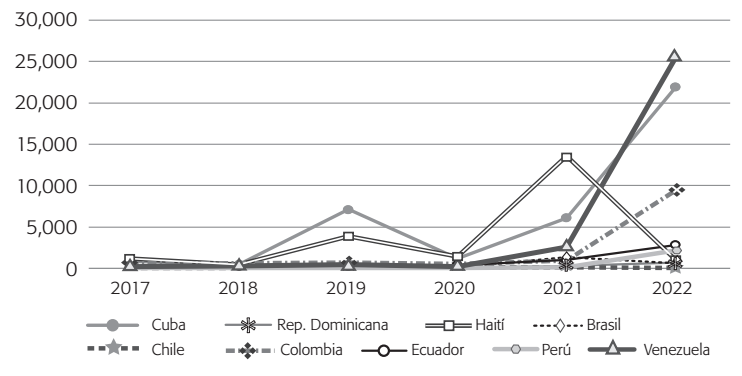

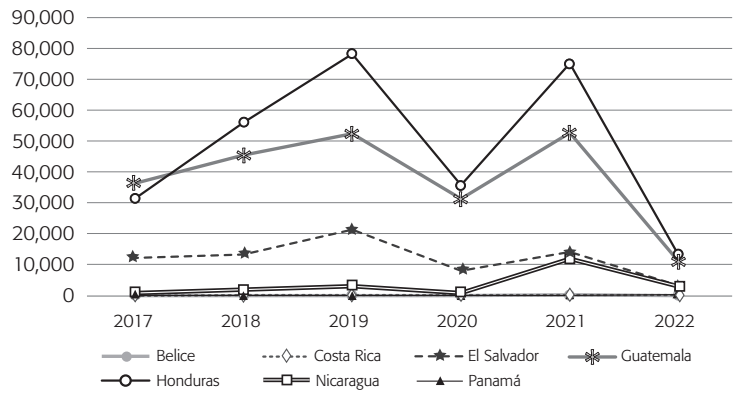

Figures 3 and 4 show that Honduran and Guatemalan migrants, followed by Salvadorans, have been the migrant groups with the highest number of detainees by Mexico. Among Central Americans, the significant number of Nicaraguans detained in 2021 is striking. However, in 2022 it is Venezuelans (Wolfe, 2021; Singer, et al., 2022) who have taken the lead, closely followed by Cubans, with fewer detainees from Central America in this period. Haitians (some of them naturalized Brazilians, Chileans, Ecuadorians and even Peruvians) and Colombians complete the list of nationalities of undocumented migrants who have been detained in recent years by the Mexican administration.

Source: Own elaboration “Monthly Statistical Bulletin” of the Migration Policy Unit of the Instituto Nacional de Migración (2017-2022). The year 2022 is counted though August.

Figure 3 Apprehensions of central American citizens in Mexico (2017-2022)

Economic Plan for Central America: The U.S. Proposal

President Joseph Biden’s administration plans to ensure that the nations of Central America, especially El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, i.e., the Northern Triangle countries, are strong, secure and capable of providing future opportunities for their own people (Rush, 2021; Sanchez, 2021). Currently, the Northern Triangle countries face enormous challenges due to violence, transnational criminal organizations, poverty, and corrupt and ineffective public institutions (Bergmann, 2019; Faret, et al., 2021).

President Joe Biden’s comprehensive policy for Central America considers the following strategies: a) develop a comprehensive four-year, four-billion-dollar regional strategy to address the drivers of migration from Central America; b) mobilize private investment in the region; c) improve security and rule of law; d) address endemic corruption and prioritize poverty reduction and economic development (Rush, 2021). Is this U.S. government proposal feasible? It will depend on the following factors: a) a redesign of U.S. immigration policy; b) strengthening the rule of law in the governments of the Northern Triangle countries; c) promoting social comptrollers to oversee U.S. and international resources; d) capacity to implement comprehensive policies to promote competitiveness and welfare and promote labor migration agreements with the United States under H2A visas.

The new U.S. immigration policy aims to redefine the agenda with Mexico and Central America, in the context of increased migration flows from the Northern Triangle, which have increased since 2011. An indicator of this impact on irregular migration flows at Mexico’s borders (Campos-Delgado and Côté-Boucher, 2021; Escamilla García, 2022)- north and south-is reflected in the fact that according to CBP (2022), this country has detained 1,734,686 irregular immigrants at the border with Mexico in fiscal year 2021 and 2,378,944 in fiscal year 2022. In this fiscal year, 1,054,084 immigrants have been removed under Title 42-immediate deportation for public health reasons-decreed by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to reduce the possibility of covid-19 infections. In the previous fiscal year (2020), U.S. authorities made 458,088 apprehensions of immigrants at the border according to CBP data (2022). This reflects a nearly 200 percent increase in apprehensions compared to FY2021, most of whom crossed the southern border to the U.S. border.

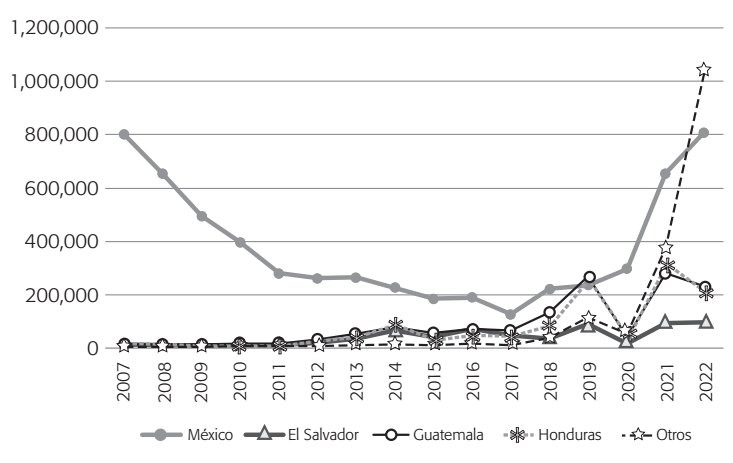

Figure 5 shows the large increase of migrant detentions from 2019, with a decrease in 2020, due to the pandemic (the number of detainees in 2020 is not lower than the number of detainees between 2009 and 2018), with severe spikes in 2021 and especially in 2022.9 This can be interpreted in several ways.

Source: Own elaboration based on USBP (n. d.).

Figure 5 Migrant apprehensions at the southern border of the United States (2000-2022)

The first is the one pointed out by U.S. Republicans, starting with Donald Trump in 2018, and continuing today with Greg Abbott (governor of Texas) and other Republicans, who claimed, in the midst of the elections, that it was the fault of President Joe Biden’s administration and its permissive policies that a large number of migrants were arriving at the southern border of the United States. It is for this reason, according to them, that measures to neutralize them need to be increased.

Another interpretation is that mass immigrant apprehension became part of an election discourse, and that it is precisely since Donald Trump put the issue on the election agenda that there has been a spike in immigration apprehensions at the southern border of the United States. This is not new; as can be seen in Figure 5: from 2001 to 2007, the number of detained immigrants was much higher than the United States had in 2018, and the debate on immigration control did not intensify at that time, not even with the possibility of terrorists entering through the Mexican border after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

In fact, U.S. government statistics show that the differentiation by nationality between Mexicans, Hondurans, Guatemalans, Salvadorans, and others has become more pronounced since 2007. Previously, the statistics referred to “Mexicans and others,” from which it can probably be inferred that Central American migration, already established in large U.S. cities, was not the object of relevant political debate, nor was it used as a partisan electoral weapon.

Figure 6 shows that Mexican citizens have traditionally been detained in greater numbers by the U.S. Border Patrol, with an upturn in the number of Hondurans and Guatemalans since 2012, which has a significant relevance in 2019 and 2021. This occurs after Trump’s threats in relation to the formation of migrant caravans made up of Central Americans, and his political message related to the construction of a wall on the border with Mexico to prevent the transit of migrants, especially Central Americans, to the United States.

Source: Own elaboration based on USBP (n. d.).

Figure 6 Migrant apprehensions at the southern border of the United States (2000-2022)

Another relevant factor shown in table 8 is how, as of 2019, not only the apprehension of Mexicans, but also of other countries, including Haitians, Cubans and, in the last fiscal year and after the change in U.S. immigration policy, Venezuelans, rise again.

The Security Agenda and the High-Level Economic Dialogue (HLED)

Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken was in Mexico in mid-September 2022 to co-chair the Second Annual Meeting of the U.S.-Mexico High Level Economic Dialogue (HLED) between the United States and Mexico-the first meeting was held in Washington, D.C. in September 2021-and to meet with President López Obrador.

The U.S. co-chairs are the Department of State, the Department of Commerce, and the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative. This second meeting addressed the goals of economic growth and development, job creation, global competitiveness, poverty reduction and inequality. In his meeting with President López Obrador, Secretary Blinken emphasized the importance of promoting semiconductor production, thereby advancing a strategic partnership in North America, with the aim of eliminating dependence on China (USDOS, 2020). The commercial importance of the relationship is manifested in the fact that according to the U.S. Census, Mexico is the second largest trading partner of the United States, which is reflected in trade of more than $384 billion in the first half of 2022.

The economic priority of the second HLED meeting is reflected by U.S. government actors: Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo, Deputy Trade Representative Jayme White, Assistant Secretary for Economic Growth, Energy and Environment Jose W. Fernandez, and Assistant Secretary for Western Hemisphere Affairs Brian A. Nichols. Secretary Blinken acknowledged that Mexico is a priority in current U.S. policy, based on shared issues: fentanyl production and trafficking, managing irregular migration in line with the commitments of the Los Angeles Declaration on Migration and Protection, climate change, and reviving value chains. Secretary Blinken reiterated that there are bilateral differences, but these are normal, given the nature of the relationship, and are addressed pragmatically and with mutual respect (USDOS, 2020).

What are the challenges of the bilateral agenda under the HLED?

a) Promote progress in investments in strategic sectors such as energy with criteria of sustainability and clean energy and the proposal for self-sufficiency in the sector and sovereignty put forward by the Mexican government.

b) Recognize the importance of addressing in a timely manner the differences generated by the consultations on the T-MEC proposed by the U.S. government on energy issues and thus avoid resorting to the corresponding panel.

These consultations within the framework of the T-MEC are normal, as there is a chapter to address trade differences, with which both countries have requested consultations: the differences over rules of origin, put forward by the Mexican government, and the demands in the energy policy sector put forward by the United States.

Another challenge is to continue strengthening the development and innovation of border crossing infrastructure between Mexico and the United States in a context of reactivating post-pandemic cross-border dynamics, against a backdrop of increased drug trafficking from Mexico. This dynamic is reflected in the fact that on a typical day at the Southwest border, U.S. border authorities process 650,178 passengers and pedestrians: (169,842 inbound international air passengers and crew, 35,795 boat passengers and crew, and 444,541 inbound land travelers (USCBP, August 2022).

Another challenge is to strengthen the migration containment initiatives proposed by the U.S. government and reactivate proposals for cooperation in economic development programs for the southern Mexican border and the Northern Triangle countries, which aim to address the underlying causes of labor mobility, in a context of increasing labor emigration and apprehensions and deportations of migrants at the southern U.S. border.

In the current fiscal year (October 2021-July 2022), 1,836,353 migrants have been detained (USCBP, August 15, 2022). These apprehensions exceed those of fiscal year 2019. While in the pandemic period (March 2020-November 2021), 2,067,205 migrants were expelled by U.S. border authorities (USCBP, 18 July 2022). These data are historic in border relations between the Northern Triangle countries and Mexico and reflect the difficulty of reducing labor mobility in the short term, given the benefits this mobility represents in terms of international remittances. For example, Mexico received a record $27.57 billion from its regular and irregular migrants abroad during the first six months of the year, reflecting an increase of 16.57 percent over the $23.65 billion in 2021, according to data from the Bank of Mexico (Banxico).

Concluding Remarks

After analyzing the border security policy under President Joe Biden’s administration and the changes in migratory flows through various initiatives such as the Central America Development Plan and the High-Level Economic Dialogue (DEA), the proposals in question highlight the need to know the impact of the U.S. border security agenda on relations with Mexico. This agenda encompasses issues of border security, national security and impacts on competitiveness and welfare.

The role of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has been strengthened in the context of the pandemic with an agenda of diverse problems (security, terrorism, drug control and irregular and regular migrants). The U.S. government’s security policy, in terms of immigration, proposes a regional approach and aims to control migratory flows under a policy of shared regional responsibility, with a “Development Plan for Central America” and the reduction of transnational crime. These alternatives have not necessarily been realized, nor have they had a significant impact on reducing migration flows to the United States. However, the greatest impact has been a more severe containment of immigration at the U.S. border.

These U.S. policy alternatives seek to manage immigration in an orderly and humane manner, promote asylum options and deter irregular immigration. The challenge for U.S. immigration policy and management is to adopt a comprehensive approach to integrating migration patterns at its southern border, with effective border control and efficient response to demands for asylum, employment, immigration regularization and family reunification.

The challenge is whether it will indeed be feasible to reduce immigration flows, considering various factors: the socio-economic and political situation of the Northern Triangle countries, Venezuela, Haiti, Cuba and Mexico; the absence of effective co-responsibility for migration; violence in the countries of the region; the labor effects of the pandemic; and the flexibilization of current U.S. immigration policy. These factors are reflected in the increase in apprehensions of irregular immigrants at the U.S. southwest border, which is the highest in U.S. history.

From the dhs perspective, it is recognized that the immigration system has problems, hence the government’s priority to secure and manage the borders while the U.S. Congress approves a fair and orderly immigration system. Against this background, it can be argued that the immigration agenda could be more relevant than the anti-drug agenda in U.S. politics, given the diversity of problems and impacts that immigration management considers, and whose visibility increases in the context of the mid-term elections in November 2022.

The border security policy agenda of President Biden’s administration has been a contentious issue in American politics, with both Democrats and Republicans having divergent opinions on how best to handle the issue. In the context of mid-term elections of November 2022, the Biden administration faced the challenge of navigating this complex issue while also ensuring that policies aligned with their broader political agenda.

One of the key challenges facing the Biden administration is to balance the need for border security with the humanitarian concerns of migrant communities. The previous administration’s approach of using harsh measures to deter migrants from crossing the border, such as family separation and the Remain in Mexico policy, drew widespread criticism from human rights organizations and the international community. The Biden administration has taken steps to reverse some of these policies, including rescinding the Remain in Mexico policy, but has faced criticism from some quarters for being too soft on immigration.

Another key issue for the Biden administration is to address the root causes of migration from Central America, such as poverty, violence, and political instability. The administration has pledged to invest in economic development programs in the region, but these initiatives will take time to yield results, and in the meantime, the U.S. will continue to face significant numbers of migrants at its southern border.

In the context of the mid-term elections, the border security policy agenda is a major issue for both Democrats and Republicans. Republicans are likely to continue to use immigration as a rallying cry to mobilize their base, as they did in the 2018 and 2020 elections. Democrats, on the other hand, must balance the need for effective border security with the concerns of progressive voters who are opposed to harsh measures such as deportation and family separation.

In conclusion, the border security policy agenda of President Biden’s administration will continue to be a contentious issue in American politics, and the administration must navigate this complex issue while also ensuring that their policies align with their broader political agenda. The mid-term elections in November 2022 were a critical moment in this ongoing debate, and both Democrats and Republicans sought gains by positioning themselves as the party of effective border security.

In sum, the border security policy agenda of President Biden’s administration has promoted a greater humanitarian exodus from countries such as Venezuela, Haiti, Cuba, the Northern Triangle countries, and Mexico, as well as a policy of greater immigration containment compared to President Trump’s administration.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)