Introduction

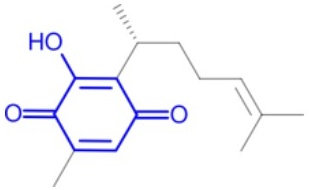

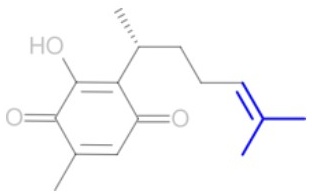

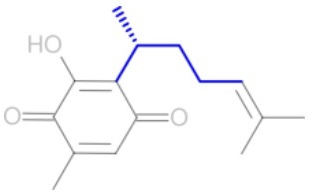

It is well known that depending on the time of year in which the pipitzahuac roots are collected, it is possible to isolate predominantly perezone [1] (1, Fig. 1) or a homogeneous mixture of (- (2-a) and (-pipitzols (2-c, Fig. 1) that naturally co-crystallize. [2-4] The extracts of this plant of the Acourtia genus have been used in traditional Mexican medicine since pre-Columbian times. The genus Perezia has been reconsidered as Acourtia and some synonyms for this plant are Acourtia humboldtoii, (BL Robinson & Green Reveal & RM King), formerly Perezia cuernavacana (BL Rob & Green), and initially Trixis pipitzahuac, (Schaff. Ex Herrera) Asteracea (Herrera).

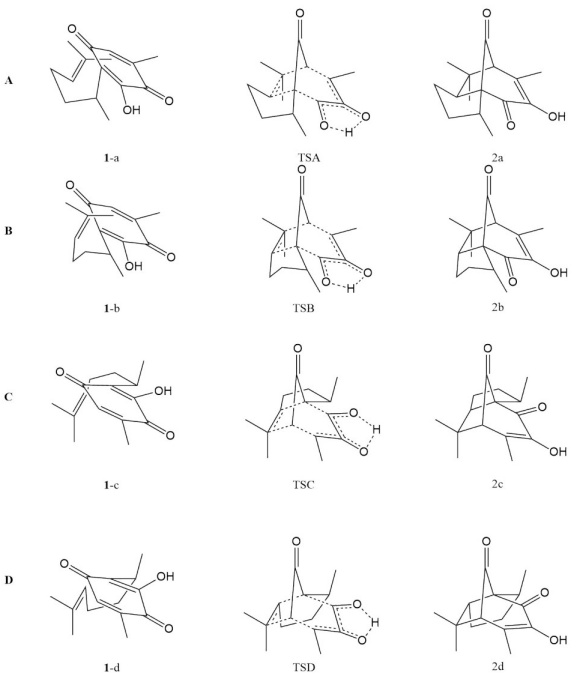

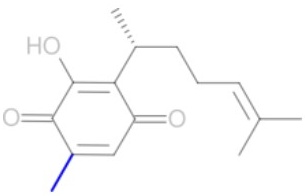

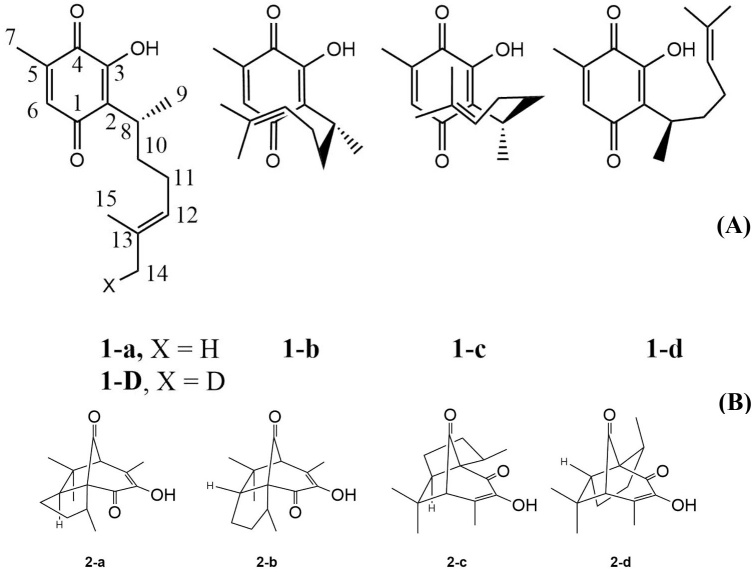

Fig. 1 (A) Perezone molecular structure with extended (1-a and 1-d) and folded (1-b and 1-c) conformers (See Fig. S1). (B) Four possible cycloaddition adducts: (-pipitzols (exo: 2-a and endo 2-b) and β-pipitzols (exo: 2-c and endo: 2-d).

In 1852 the Mexican pharmacist Leopoldo Río de la Loza isolated perezone in its crystalline form from a crude extract that had been provided to him by Pascual Díaz Leal by sublimation from the dried root, or by alcohol extraction followed by recrystallization from gasoline.[5] He reported the first elemental analysis developed in Mexico using the method implemented by Professor Justus von Liebig in Germany. [6] Río de la Loza analysis turned out to be erroneous, as a nitrogen atom was incorrectly assigned to the molecular formula, [7] nonetheless this assay should be considered a historical milestone, being the first attempt to carry out Liebig´s method for organic elemental analysis in America.

In 1857 Severiano Pérez reported the finding of a white and crystalline substance as a component of the pipitzahuac resin, which he initially called fructicosina and later pipitzahuina,[8,9] two ways for naming pipitzols that were lost over time. Pérez described the first isolation of pipitzols through the accidental thermal transformation of perezone, obtaining them as a crystalline by-product of its purification using sublimation, however, Pérez only described some physical properties and did not delve the molecular composition of this by product. Pérez considered that Río de la Loza´s perezone was a mixture formed by pipitzoles contaminated by colored compounds that imparted its color to the mixture. A serious mistake.

At the turn of the century, Remfry [10] obtained pipitzols by a thermal reaction of perezone but it was until 1965 when the first mechanism for this transformation was proposed, [1,11] in order to support perezone´s connectivity proposal, which resulted to be wrong. This mechanism, suggested the intermediation of a cyclobutane, followed by two alkyl group migrations for the formation of the pipitzols. [1]

The connectivity of prerezone (1) was established the same year when four independent works were published. By means of 1H NMR analysis, it was finally established that the correct connectivity of quinone substituents exhibits a methyl group and a hydrogen atom on the same side of the quinone.[12-15] With the connectivity described, it was possible to report the first total synthesis of perezone.[16] The determination of the chemical structure of perezone allowed to propose an adequate mechanism for the formation of pipitzols, whose structure had been determined shortly before by Romo et al. [1] Initially they established that the product of the reaction consisted of a mixture of two diasteromers, in which all the stereogenic centers formed in the reaction had opposite configurations, but since the stereogenic center at C8 (of R configuration, Fig. 1) is kept constant, diasteroisomers are formed.

Experimentally, the selective oxidation of the methyl vinyl group at position 14, located trans with respect to the alkyl chain of 1 using selenium oxide, produced a pair of reaction products from which the aldehyde was isolated, and subsequently reduced with sodium borodeuteride and deoxygenated.[17] In this way, it was possible to prepare monodeuterated perezone at only one methyl group.When subjected to the thermal conditions of cycloaddition, pipitzols were formed, in which there were no scattering labels, so this mechanism was interpreted to correspond to a class B cycloaddition [(4s + (2s][18] or as a sigmatropic reaction of [1,9] order.[17] Furthermore, it was observed that in thermal conditions the proportion of the obtained pipitzols was similar, without induction of the stereogenic center. [17]

Because pipitzols have their biogenetic origin in perezone and both are natural products, their study is part of our interest in the terminal biogenesis of terpenes. [19,20]

Results and discussion

Concerted cycloaddition of perezone (1)

The folded conformers of perezone which are the precursors of pipitzols, present two easily differentiable arrangements according to the face of the quinone on which the side chain approaches, and each of them presents two possible orientations of the double bond; this is whether the side chain approaches exo (1-a and 1-c,Fig. 2) or endo (1-b and 1-d). It is important to notice that to date only compounds originating from the exo approach have been isolated from the plant and obtained by synthesis.[1-4,16,18] Deuterium labeling experimentation on perezone´s C14 methyl group (structure 1-d, Fig. 1), demonstrated complete preservation of deuterium on methyl C14 of the endo adduct, thus assuring the concerted mechanism nature.[16,21,22]

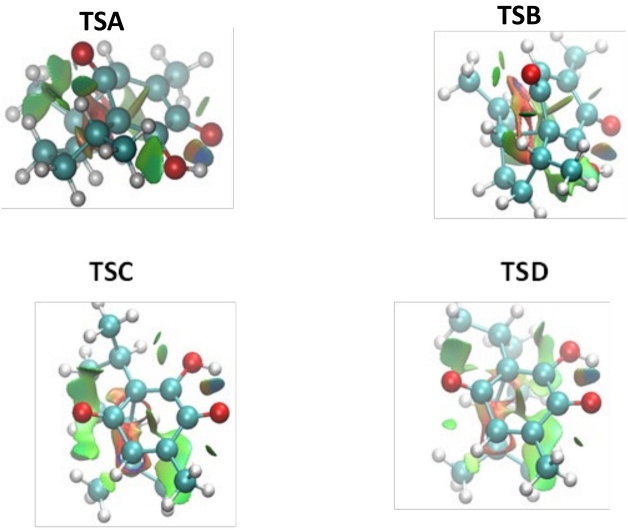

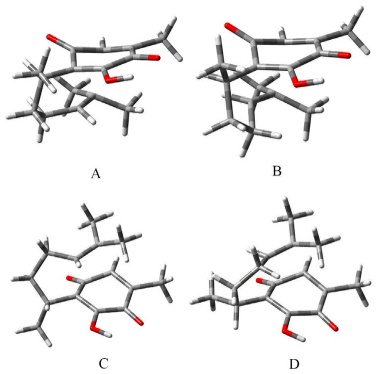

With the available conformers and the structure of the two isolable diasteromeric pipitzols, the search for the transition states associated with the four possible approaches was undertaken. (See Table S3) All four transition states are characterizable and are presented in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3 Geometries of the transition-states A, B and C, D of the cycloaddition path to produce α- and β- pipitzols, respectively.

The mere existence of a transition state formally concludes the problem of the existence of the folded conformers of perezone as in this case, it has allowed the characterization of the four transition states associated with the formation of the four possible pipitzol diastaroisomers. On a surface of any nature, (potential energy in this case, and electron density or coulombic potential as an example), the existence of a point of (3, -1) curvature, (associable with a transition state) in which two curvatures are negative and one positive, the energy reaches a maximum within the plane defined by the corresponding axes and a minimum along the third axis which, is perpendicular to the previous plane. The existence of a transition state is a necessary and sufficient condition for the associated minima and maxima to exist, regardless of its vibrational nature.

The forming sigma bond distances and the pyramidization (() of the involved carbon atoms are presented in Table 1. In the transition state that leads to the formation of exo-β-pipitzol, the C2-C12 bond distance is the largest in all cases (see entry C, Table 1), while C6-C13 is the shortest. A larger bond could diminish the angular strain and allow for a more synchronous approximation of the two olefin carbon atoms towards the quinone center, affecting the experimented vibrational degrees of freedom. This can be understood in terms of the greater participation of the second bond in the stability (or the shorter length of the C6-C13 bond).

Table 1 Bond distances (Å) and pyramidalization ((, in Å) are associated to the formation of C2-C12 and C6-C13 bonds in their transition states.

| Structure | DC2-C12 | DC6-C13 | ΔC2 | ΔC12 | ΔC6 | ΔC13 |

| A α-Exo | 1.9956 | 2.1305 | 0.20378 | 0.12886 | 0.21279 | 0.17533 |

| B α-Endo | 2.0164 | 2.0856 | 0.15240 | 0.14404 | 0.18772 | 0.16608 |

| C β-Exo | 2.1398 | 2.0070 | 0.17319 | 0.12073 | 0.17573 | 0.14644 |

| D β -Endo | 1.9899 | 2.0946 | 0.14741 | 0.13233 | 0.16969 | 0.14645 |

Table 2 shows the energy parameters for the formation of the four possible products of cycloaddition using tetralin as an implicit solvent.[1] In terms of the stability of the adducts, the transition states that lead to the exo isomers are ca. 6.0 kcal/mol more stable than the endo ones, being enthalpy as the major contributor term. The angular strain on endo products, causes a stability loss reflected mainly on the enthalpic term, with values matching the T(S term (T = 480 K), while for the exo products the T(S term represents 40 % of the enthalpy value. Lastly, the exo adduct derived (- and β-pipitzols are 10.8 and 11.8 kcal/mol more stable with respect to their parent conformer.

Table 2 Kinetic and thermodynamic data for intramolecular cycloaddition [5 + 2] of perezone at 480 K, 1 atm and tetralin dielectric constant. The free energy (G) and enthalpy (H) values are in kcal/mol while those of entropy (S) are in cal/K·mol.

| Kinetic data | Thermodynamic data | |||||

| Reaction* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| A α-Exo | 30.4 | -14.5 | 37.4 | -18.0 | -15.0 | -10.8 |

| B α-Endo | 36.6 | -15.2 | 43.8 | -7.4 | -17.2 | 0.8 |

| C β-Exo | 32.5 | -11.8 | 38.2 | -19.0 | -15.3 | -11.8 |

| D β -Endo | 38.6 | -12.3 | 44.4 | -7.3 | -12.9 | -1.1 |

See Fig. 2

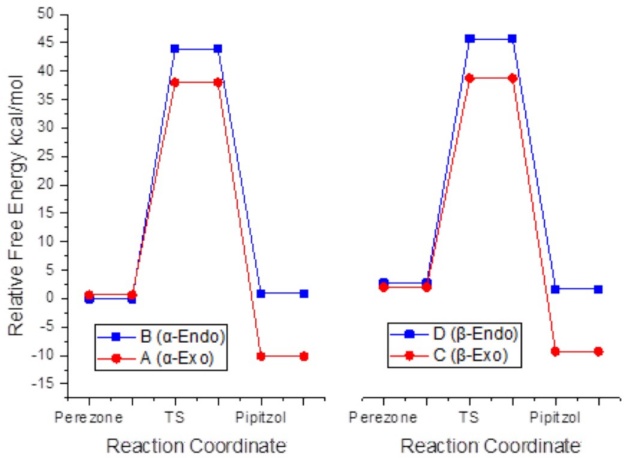

Data presented in Fig. 4, allowed us to quickly conclude on why, neither (- nor β- adducts generated by the side chain endo approximation have ever been observed. The activation energy for the former is 6.5 kcal/mol while for the latter is 6.3 kcal/mol higher with respect to the corresponding transition states for the formation of exo products. The formation of β-pipitzol requires overpassing an activation energy barrier of (G≠ = 37.4 kcal/mol, while for α-pipitzol this energy is of 38.3 kcal/mol. Therefore, a resulting energy difference of ((G≠= 0.8 kcal/mol led to an approximate proportion of 70/30. [23]

Fig. 4 Intramolecular [5+2] cycloaddition paths of perezone to produce (- and (-pipitzols at M06-2X/6-311++G(2d,2p) level of theory in tetralin as implicit solvent.

Activation enthalpy favors the formation of stable exo adducts, since angular strain is larger in endo adducts. Selectivity towards exo adducts can be explained in terms of steric compression. Careful observation of the endo adducts allows to identify a severe deformation in the environment at C12 carbon. The steric demand that the five-membered ring closure requires is responsible for hindering the endo isomers formation. These isomers have not been observed, not even by heating methods in which the vibrationally excited states would be feasible, as it has been proposed as mechanisms without the existence of folded conformers.[24]

The sigma bond formation process is asynchronous since the C2-C12 bond is shorter than the C6-C13 one and the stability of C13 is attributable to its tertiary carbocation character. Nevertheless, the pyramidization degree is larger on C6 than C2, as it is with the C13 and C12 pair, probably originated from the intense angular tension upon the formation of the second bond and the bicycle closure.

The stability of C13 is originated as well by the hyperconjugation arising from two vicinal hydrogen atoms oriented in such a way that σC-H is held perpendicular to the carbon atom plane. The hyperconjugation contribution to stability is not ideal since C13 has a certain degree of pyramidization.

The approximation of the lateral chain towards the quinone group is defined by the dihedral angle C1-C2-C8-C18, with values of 98.1°and 52.0º for the transition states of exo adducts A and C (which lead to the formation of (- and β-pipitzol), respectively and the endo adducts with values of 129.4° and 122.4° for B and D, respectively (Table 1). The lateral chain folding entails the consecutive gauche conformation along that segment, with an ideal dihedral angle of 60º. In this regard, the endo transition states show an intense twisting concerning exo ones. The C2-C8-C10-C12 dihedral angle has values of 30.8° and 30.5º for A and C, respectively and 24.5° and 12.4º for endo B and D transition states, respectively. Nevertheless, the C8-C10-C11-C12 segment has a more relaxed geometry in transition state A of 56.6º, while the same segment in transition state C shows a high degree of eclipsed conformation with a value of 3.9º. The same segment on B and D transition states show dihedral angles of 19.9° and 30.2° revealing the angular tension generated on these systems. Finally, the endo and exo orientations are described by the C10-C11-C12-C13 dihedral angle which has values of 152.5°, 133.4°, 157.6° and 160.5º for A, C, B and D transition states, respectively.

Topological analysis of the electron density

According to Professor Houk intermolecular interactions as well as deformations experimented by the reacting fragments in transition states determine both the favored products and the activation energies.[25] Since the fragments involved in the formation of pipitzols belong to the same molecule, carrying out deformation energy analysis is not possible. Instead, it was decided to obtain atomic properties under the framework of Bader’s Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules (QTAIM).[26,27]

Table 3 shows the energetic differences corresponding to the evolution of 4 fragments of perezone: (F1) the quinoid ring, (F2) the isopropenyl group (F3) the alkyl chain bonding the first two, and (F4) the methyl group. The process comprises the change of the reagents to the corresponding transition states. This data indicates the isopropenyl group is responsible for the increase in energy required to reach the transition states of the 4 isomers. Charge transfer to the quinoid ring and pyramidalization accounts for the destabilization. The reduction in stability of F2 is compensated by the quinoid ring, which is increasingly stabilized when F2 approximates in endo fashion. The exo configuration, observed experimentally, is explained by the contributions of F3, since the steric compression which deforms the fragment is decisive as for the exo conformers, F3 is strongly stabilizing with contributions of -11.67 and -11.60 kcal/mol for the α- and β conformers respectively. The α-endo conformer is destabilizing with a contribution of 6.33 kcal/mol (18.00 kcal/mol overall with respect to the α-exo isomer). β-endo contribution of -2.64 kcal/mol is only slightly stabilizing. Hence, the steric compression of the lateral chain is decisive for the stereoselectivity of the exo isomers over the endo.

Table 3 Change in Potential Energy related to four fragments of perezone. Values in kcal/mol. (F indicates fragment)

Experimentally, the formation of (-pipitzol is similar to the formation of the β-isomer, in that the two adducts are obtained in the same proportion. The contributions to free energy show this behavior has its origin in the activation enthalpy, since in all cases the activation entropy maintains similar values and points towards the decrease of the well-known degrees of freedom common to cycloaddition reactions. Additionally, entropy is highly relevant for (-isomers with respect to β-isomers.

To study the influence of the steric clash as the energy barrier of the compounds studied here, a calculation of the non-covalent interactions (NCI) based on the reduced density gradient s(r) was performed.

The reduced density gradient s(r) is a dimensionless quantity especially suited to identify noncovalent interactions that show the inhomogeneity of the electronic density. The capability of s(r) to recognize chemical hallmarks is reflected by the positions of its critical points (CP). The CP in s(r) is located at critical points in the electron density (∇ρ(r)=0), and at points where a complex balance between ρ(r) and von Weizsäcker kinetic exists.[28] The latter are blind to QTAIM theory and correspond to intramolecular weak interactions. In this approach, the classification of the NCI is done in terms of the maximum variations in the contributions to the Laplacian, along with the axes, corresponding to the eigenvalues (λi) of the electron-density Hessian matrix. The sign of λ2 enables us to distinguish between the different types of weak interactions, attractive and repulsive (such as steric repulsions), while the electron density lets us assess the interaction strength. To gain a deeper understanding of factors controlling the selectivity trends, we performed an analysis of NCI in TSs based on the study of the density reduced gradient.

Firstly, we considered the endo-exo selectivity in the thermal reaction to prove if the steric compression of the lateral chain is decisive for the stereoselectivity of the exo isomers over the endo, as is suggested by the atomic properties calculated using QTAIM.

Fig. 5 collects NCI surfaces of TSA, TSB, TSC, and TSD. We can observe a complicated group of NCI surfaces, where bicolored isosurfaces appear reflecting stabilizing features counter-balanced by destabilizing interactions due to steric crowding. Due to this complexity, it is not possible to point out that NCI is the cause of the observed selectivity. Therefore, we have performed an integration of the electronic density in NCI. The integration of the electronic density in volume elements, defined by sign(λ2)ρ ranges, has been proved to be a useful tool for the estimation of the strength of the NCI. [29] We performed the integration of ρ in two ranges, corresponding to attractive (-0.05 ≤ sign(λ2)ρ ≤ 0.00) and the repulsive ones (0.00 ≤ sign(λ2)ρ ≤ 0.05). The results are depicted in Table 4.

Table 4 Repulsive and attractive electronic density integrals and their difference for TSs in the thermal reaction.

|

|

||

| Attractive | Repulsive | |

| TSA | 0.39 | 4.66 |

| TSB | 0.35 | 4.68 |

| TSC | 0.37 | 4.66 |

| TSD | 0.37 | 4.72 |

Analyzing the integral values for TSA and TSB in Table 4, it is clear that the attractive and repulsive NCI seems to govern the endo-exo selectivity. TSA presents the higher value of attractive NCI where the difference relative to TSB is equal to 0.04 u.a. On the other hand, the repulsive NCI integrals in the TSB are slightly higher than in the TSA case by 0.02 u.a. Therefore, we can conclude that both sorts of interaction lead the exo approximation as the preferred one. That is, in the exo TS the attractive NCI are maximized whereas the repulsive ones are slightly alleviated.

In the β-pipitzol case, the density integral values show that TSC present less steric repulsion than TSD with a difference of 0.06 u.a., whereas the value of the attractive density integral are the same. Therefore, these results allowed us to conclude that the exo preference in this instance is explained by the less steric hindrance in the exo approximation.

Methodology

All electronic structure calculations were performed under the Density Functional Theory (DFT) methodology, implemented in Gaussian09 software. [29] The stationary state geometries (reactants, transition states and products) were optimized using the meta-GGA M06-2X hybrid functional with the 6-311++G(2d,2p) Pople basis set; containing divided triple zeta valence and polarization functions on light and heavy atoms. M06-2x functional was employed since it has been recommended to study kinetics and thermochemical properties.[31] The geometry optimizations were carried out considering implicit solvent effects calculated with the SMD model along with the UAHF molecular cavity; tetraline solvent was employed for the thermal mechanism, while dichloromethane for the catalyzed mechanisms. Normal modes of vibration analysis allowed us to determine the nature of the stationary transition states (TS and energy minima displayed one and zero frequencies, respectively). Zero-point vibrational energy (ZPVE) and thermal corrections at 480 K (experimental conditions reported by J. Romo and coworkers[2] for the thermal mechanism). The intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) mapping was conducted in order to corroborate that transition structures were connecting the proposed minima. Changes in potential energy related to the different fragments of perezone were obtained through the topological analysis of the electron density of perezone using AIMAll software.[32] The NCI calculations were performed by means of a NCIPLOT4 program,[29] and the resulting isosurfaces were visualized with the Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD) software[34] following the next colour code: blue for attractive interactions, green for dispersive interactions (attractive or repulsive) and red for repulsive interactions.

Conclusions

Studying the concerted mechanism of perezone transformation in to pipitzols, it is feasible to explain why only products originated from the exo approximation of the lateral chain have been described in the literature. The employed computational methodology at the M06-2X/6-311++G(2d,2p) level of theory allows stablishing the selectivity of the reaction and the origin of the isotopic labelling distribution observed in the thermic process The formation of exo-isomers with respect to the endo has its origin in the conformational arrangement of the side chain, which undergoes severe steric compression in the second case.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)