Introduction

Breast and cervix cancer are the most common cancer-related death cause among females worldwide. Thus, it is crucial to search for newer therapies that can help prevent and treat this illness, besides lessening the side effects of available therapies (Khosropanah et al., 2016; Saenglee et al., 2016). The use of medicinal plants in the treatment of diseases is increasing due to the benefits against chronic diseases like cancer, since plants have bioactive compounds, playing a vital role in the development of pharmaceuticals (Abdulla et al., 2014).

The therapeutic potential of medicinal plants generally associates to the antioxidant activity of phytochemicals, mainly phenols and flavonoids, closely linked to their ability to suppress cancer cells’ growth through reduced oxidative stress (Marvibaigi et al., 2016). However, the cellular mechanisms by which the phenols elicit these anticancer effects are multifaceted (Sorice et al., 2016).

Q. sideroxyla and P. durangensis are forest timber species in Mexico. Their primary non-timber uses are for edible harvesting seeds and even as medicine in the treatment of disorders like ulcers and inflammatory problems (Bermejo and Pontones 1999; Luna et al., 2003). Previous studies reported antibacterial effects, high phenolic content, and antioxidant properties in P. durangensis extracts (Rosales-Castro and González-Laredo, 2003; Rosales-Castro et al., 2006). Extracts from Q. sideroxyla have shown hypoglycemic and genotoxic effects, amelioration of oxidative stress evaluated in a murine model, high antioxidant capacity, anti-inflammatory effects, and anticarcinogenic activity in rat colon (Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2015; Soto-García et al., 2016). The main bioactive compound of these species identified is flavan-3-ols in Q. sideroxyla (Rosales et al., 2012), and flavonoids like taxifolin and quercetin in P. durangensis (Soto-García and Rosales-Castro, 2016).

Many investigations reported catechin, taxifolin, and quercetin as compounds with cytotoxic activities (Moreira et al., 2013; Evacuasiany et al., 2014; Moreno-Jimenez et al., 2015; Alzaharna et al., 2017; Rameshthangam and Chitra, 2017). Thus, this research aimed to determine the cytotoxic activities of polyphenolic extracts from P. durangensis and Q. sideroxyla bark against MDA MB-231, MCF 10A HeLa, and HSF-1184 cell lines.

Methods

Plant material

The bark collection was in January 2014 in Pueblo Nuevo, Durango, México. María Del Socorro Gonzalez Elizondo (taxonomist) identified the samples, and botanical specimens deposited at the Herbarium in CIIDIR-IPN, Durango, with vouchers number 42842, 428443, 42844 for Q. sideroxyla and 93, 97, 99, 100, 101 for P. durangensis. The bark preparation consisted in a mixture to make a unique sample, drying at room temperature, milled (mesh 40), and finally stored at 4 °C in paper bags until further use.

Extracts preparation and purification

The bark powder (10 g) was twice soaked with 50% ethanol (ethanol/water 50:50 v/v) (2 x 300 mL) with stirring at room temperature for 24 h, then filtered through a Whatman filter paper no. 1. The extracts were combined, filtered, and then vacuum evaporated at 40 °C until ethanol was removed. A portion of the remaining aqueous extract was dried and identified as crude extract (CE); the other portion went through a liquid partition process with ethyl acetate (3 x 100 mL). The organic phase was vacuum evaporated at 40 °C and identified as the organic extract (OE).

ESI-MS analysis

To obtain the P. durangensis and Q. sideroxyla OE spectra, we used a micrOTOF-QII mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) equipped with an electrospray ionization source (ESI). The parameters were set as capillary 2700 V, nebulizer pressure 1.2 bar, dry gas flow 11 L/min, and dry gas temperature 200 °C and the sample ran in the negative ion mode. The scan range was from 50 to 3000 m/z.

Cytotoxic evaluation

Cell lines and culture conditions

Human breast cancer (MDA-MB-231), human cervical cancer (HeLa), and non-cancer (MCF-10A and H-1184) cell lines were from the American Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC, USA). The cultures of HeLa, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, and H-1184 cells were in DMEM high glucose (Gibco Lab, Grand Island, NY) in 10% (MDA-MB-231 was 5%) bovine fetal serum and antibiotic 1X (streptomycin/penicillin 10000 U/mL, Gibco LabGrand Island, NY). The culture of MCF-10A was in DMEM/F12 medium with 10% bovine fetal serum, incubated at 37 °C in a humid atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Cytotoxic assay

The cytotoxic assay was measured using MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylth-iazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay. Each cell line was plated in 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well and incubated for 24 h (37 °C, 5% CO2 air humidified) to allow them to adhere to the plate. Different concentrations of the CE and OE from P. durangensis and Q. sideroxyla were prepared (from the stock solution) and added to the culture medium to treat the cells, and cells incubated for another 72 h under the same conditions, using cells without treatment as a negative control. At the end of the experimental period, 100 μL of MTT dissolved in medium (5 mg/mL) were added to each well and incubated for another 2.5 h. Then, the medium was removed, the formazan crystals dissolved in 150 μL DMSO, and the absorbance measured at 550 nm in a spectrophotometer (Sinergy Biotek Instruments, Winooski, VT). In order to determine viability and the concentration leading to 50% inhibition of the viability, the determination of IC50 was by regression analysis using the following equation:

% Viability = Abs treated cells / Abs control cells × 100 Statistical analysis

The results reported are as the mean and the standard deviation (SD) of at least two independent experiments. The data analysis was by One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by post-hoc Turkey test, using a significance level of α ≤ 0.5 to determine statistical significance. The statistical analysis software used for these analyses was Statistica 7.

Results and discussion

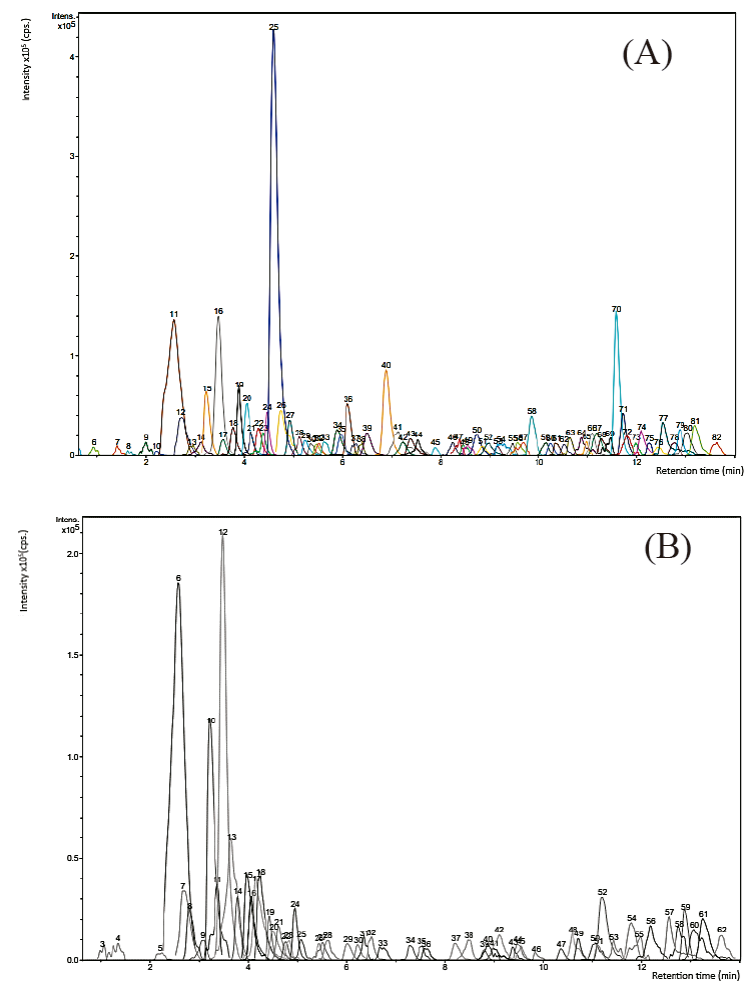

The characterization of organic extracts (OE) from P. durangensis and Q. sideroxyla was by the analysis of the major peaks identified based on elution order, and that of all compounds was by interpreting their mass spectra obtained by the HPLC-ESI-MS, considering previously reported data. Figure 1 (A and B) shows the total ion chromatogram (TIC) of extracts from species studied. Several investigations reported cytotoxic effects of some Pine and oaks species on different cell lines that were related to compounds with the biological activities (Şöhretoğlu et al., 2012; Moradi et al., 2016; Li et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2016; Amessis-Ouchemoukh et al., 2017; Sarmeili et al., 2017).

Fig. 1 Total ion chromatogram. (A) OE from P. durangensis.

11= Procyanidin dimer, 16= (+)-Catechin/(-)-Epicatechin, 25=

Dihydroquercetin (Taxifolin), 40= Myricetin, 70= Kaempferol; (B) OE from

Q. sideroxyla. 6= Procyanidin

dimer, 10= Procyanidin dimer B1, 12= (+)-Catechin/(-)-Epicatechin;

Procyanidin dimer, 13= (+)-Catechin/(-)-Epicatechin.

Fig. 1. Cromatografia de iones totales. (A) OE de

P. durangensis. 11= Dimero de

procianidina, 16= (+)-Catequina/(-)-Epicatequina, 25= Dihidroquercetina

(Taxifolina), 40= Miricetina, 70= Kaempferol; (B) OE de

Q. sideroxyla. 6= Dimero

procianidina, 10= Dimero procianidina B1, 12= (+)-Catequina/

(-)-Epicatequina; dinero Procianidina, 13=

(+)-Catequina/(-)-Epicatequina.

Table 1 shows the main constituents of pine bark, where the compounds of the peaks 11, 12, 15, 16, 25, 36, 40, 41, and 58 coincide with compounds recently reported by Rosales (2017) in P. durangensis bark, demonstrating the presence of flavonoids like procyanidins and the abundance of taxifolin. Other TIC peak constituents were compared with the relevant literature in order to obtain a tentative identification (most studies on compounds of Pinus and Quercus bark) finding: kaempferol and eriodictyol ([M-H]- 285 and 287 respectively; De la Luz Cádiz-Gurrea et al., 2014), taxifolin-o-hexoside ([M-H]- 465; Cretu et al., 2013), β-hydroxypropiovanillone glucoside ([M-H]- 357; Karonen et al., 2004), HHDP-galoyl-glucose ([M-H]- 357; Fernández et al., 2009), trigalloyl glucose ([M-H]-635; Mucilli et al., 2017), (Epi)catechin-3-O-glucoside-gallate ([M-H]- 603; Jiménez-Sánchez et al., 2015), t-caftaric acid ([M-H]- 311; Pardo-García et al., 2014).

Table 1 Compounds identified by ESI-MS in the P. durangensis bark organic

extract.

Tabla 1. Identificación de compuestos por

ESI-MS en extractos orgánicos de corteza de P.

durangensis.

| # Peak | RT (min) | Mass [m/z]- | Suggested compound |

| 11 | 2.6 | 577.1320 | Procyanidin dimer |

| 12 | 2.7 | 289.0699 | (+)-Catechin/(-)-Epicatechin |

| 15 | 3.3 | 577.1321 | Procyanidin dimer |

| 15 | 3.3 | 865.1916 | Procyanidin trimer |

| 16 | 3.5 | 289.0706 | (+)-Catechin/(-)-Epicatechin |

| 16 | 3.5 | 579.1490 | Catechin dimer |

| 19 | 3.9 | 465.1041 | Taxifolin-O-hexoside |

| 25 | 4.6 | 303.0506 | Dihydroquercetin (Taxifolin) |

| 34 | 5.9 | 633.1210 | HHDP-galoyl-glucose |

| 36 | 6.1 | 317.0616 | Myricetin |

| 36 | 6.1 | 635.1369 | Trigalloyl glucose |

| 39 | 6.5 | 287.0539 | Eriodictyol |

| 40 | 6.9 | 317.0639 | Myricetin |

| 40 | 6.9 | 635.1369 | Trigalloyl glucose |

| 41 | 7.1 | 331.0448 | Pinomyricetin (myricetin-6Me) |

| 50 | 8.7 | 357.1330 | b-hydroxypropiovanillone glucoside |

| 58 | 9.9 | 301.0679 | Quercetin |

| 58 | 9.9 | 603.1440 | (Epi)catechin-3-O-glucoside-gallate |

| 70 | 11.6 | 285.0759 | Kaempferol |

| 77 | 12.5 | 311.1854 | t-caftaric acid |

| 79 | 12.9 | 293.1740 | Unknown |

The polyphenolic profiles of Q. sideroxyla shown in Table 2 includes procyanidin dimer of catechin/epicatechin compounds (peaks 6, 10, 12, and 13) which is, by far, the dominant polyphenols in bark extract from this species, also reported in previous studies (Rosales et al., 2012). Other compounds present in the extract also compared with previously reported literature, resulted in the tentative identification of constituents such as Quercetin 3-O-glucoside and t-caftaric acid ([M-H] - 463 and 311 respectively; Pardo-García et al., 2014), Ellagic acid-rhamnoside ([M-H]-447; Santos et al., 2013) gallic acid hexoside ([M-H]- 331; Lorenz et al., 2016), taxifolin ([M-H]- 303; Rosales et al., 2017). Other unknown compounds reported in barks detected in both extracts are also included ([M-H] - 293; Mämmelä et al., 2000).

Table 2 Compounds identified by ESI-MS in the Q. sideroxyla bark organic extract.

Tabla 2. Identificación de compuestos por ESI-MS en

extractos orgánicos de corteza de Q.

sideroxyla.

| # Peak | RT (min) | Mass [m/z]- | Suggested compound |

| 6 | 2.6 | 577.1319 | Procyanidin dimer |

| 7 | 2.7 | 289.0702 | (+)-Catechin/(-)-Epicatechin |

| 10 | 3.2 | 577.1323 | Procyanidin dimer B1 |

| 12 | 3.5 | 289.0704;579.1489 | (+)-Catechin/(-)-Epicatechin; Procyanidin dimer |

| 13 | 3.7 | 289.0702 | (+)-Catechin/(-)-Epicatechin |

| 14 | 3.8 | 577.1307 | Procyanidin dimer |

| 15 | 4.0 | 463.0873 | Quercetin 3-O-glucoside |

| 18 | 4.2 | 447.0920 | Ellagic acid-rhamnoside |

| 21 | 4.6 | 303.0498 | Dihydroquercetin |

| 37 | 8.2 | 331.2490 | Gallic acid hexoside |

| 57 | 12.5 | 311.1848 | t-caftaric acid |

| 59 | 12.9 | 293.1736 | Unknow |

In previous studies, we have identified some of the major phenolic compounds of crude P. durangensis and Q. sideroxyla bark extracts by HPLC-DAD (Soto-Garcia and Rosales-Castro, 2016); these results, together with those obtained in this research, confirm the reproducibility of their bioactive compounds in bark extracts, like catechin in both species.

The P. durangensis and Q sideroxyla CE and OE bark cytotoxic effects were also evaluated on a cell line from human breast carcinoma, estrogen receptor-negative (ER-) MDA-MB-231, and cervix carcinoma cell line HeLa. Non-tumorous MCF-10A and HSF-1184 cells, used as controls, allowed comparing the effects produced by the extracts in healthy and tumor cells.

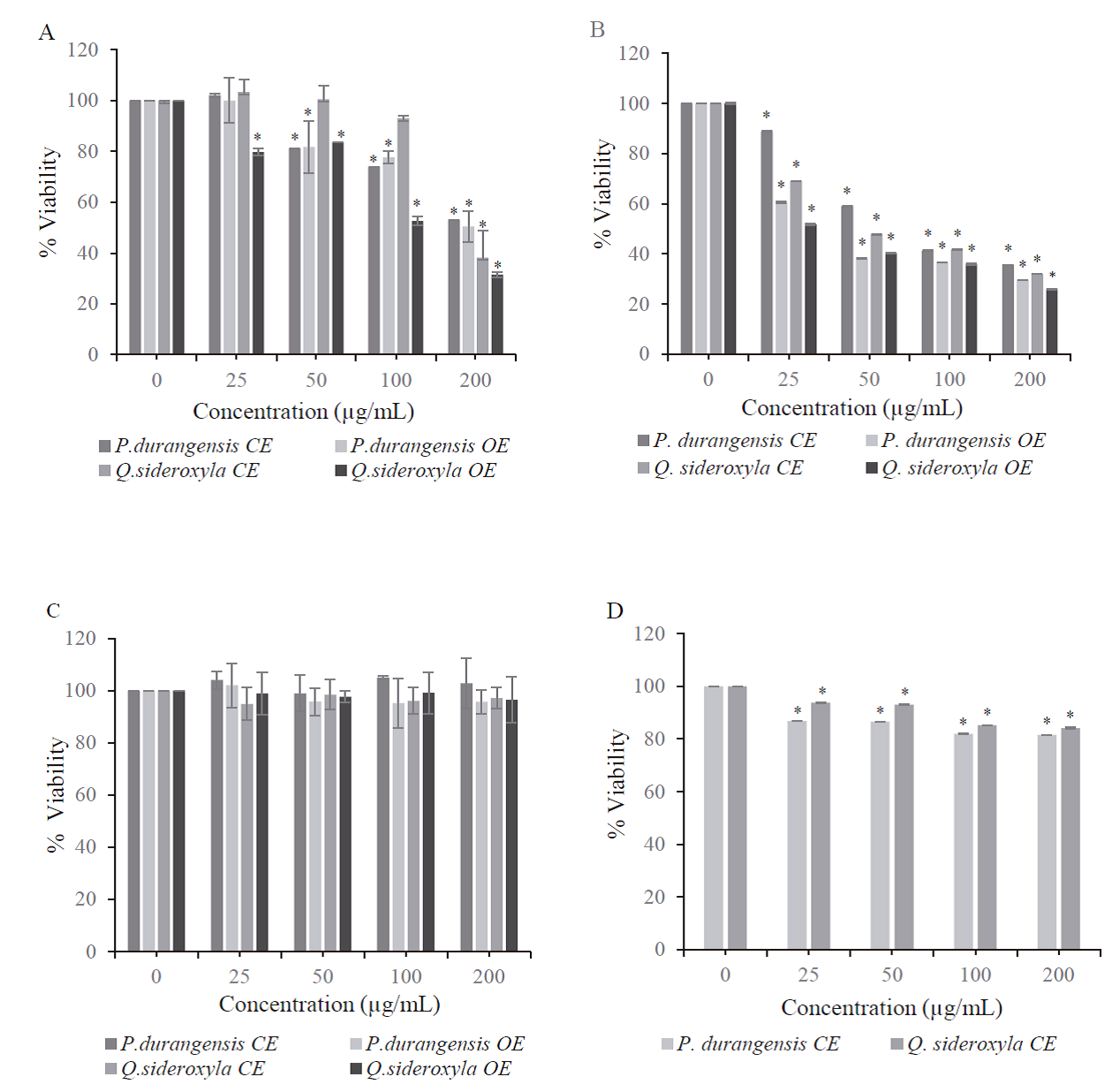

Results showed that crude extract and organic extract of both species have cytotoxic activity on cancer cell lines growth. A concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2 A, B, C), becomes statistically different (p≤ 0.05) between treated and untreated cells (MDA-MB-231 and HeLa cell lines), nevertheless they were not cytotoxic to the non-tumorous HSF-1184 cell line.

Fig. 2 Cytotoxic effect of P. durangensis and

Q. sideroxyla bark extracts on

cells. (A) HeLa cells, (B) MDA-MB-231 cells, (C) HSF-1184 cells and (D)

MCF-10A. Percent cell survival in the control group (untreated cells)

assumed as 100. Results are expressed as the mean ± SD of two

independent experiments (n=4). Significant difference *p ≤ 0.05 versus

the control group.

Fig. 2. Efecto citotoxico de los extractos de corteza de

P. durangensis y

Q. sideroxyla sobre las

celulas. (A) Celulas HeLa, (B) Celulas MDA-MB-231, (C) Células HSF-1184

y (D) células MCF-10A. El porcentaje de supervivencia celular en el

grupo de control (células no tratadas) se asumió como 100. Los

resultados se expresan como la media ± DE de dos experimentos

independientes (n = 4). Diferencia significativa * p ≤ 0.05 frente al

grupo de control.

The crude extracts showed a slight reduction in cell viability on normal breast MCF-10A cells, 20 % approximately (Fig. 2 D), even at the higher applied doses. These results indicate that the P. durangensis and Q. sideroxyla extracts preferentially reduced the growth of the tumoral cell while not affecting the healthy cell line. The role of phenolic compounds in the extracts is essential, since it has been observed that polyphenols such as catechins induce apoptotic cell death in MDA MB-231 cell lines but not in normal cells (MCF 10-A) (Farhan et. al., 2016). The CE of both species presents catechin in their compounds, explaining the selective effect on MCF-10A.

Several investigations reported that the effects obtained on cell proliferation relate to dose and cell type, implying a different sensitivity by different cell lines (Gezer et al., 2015; Anlar et al., 2016). It has also been reported that the selective activity of cytotoxic compounds against healthy (MCF- 10A) and tumor cells is due to a broad spectrum of mechanisms responsible for the resistance. These include differences in the subcellular localization of Bik and differences in mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis that explain the sensibility exerted by the bark extracts from P. durangensis and Q. sideroxyla in the cell lines (Studzinska-Sroka et al., 2016).

IC50 determination provides further clarification of both species’ crude and organic extracts behavior in different cell lines (Table 3). It shows that organic extracts of both species have a major cytotoxic effect on MDA-MB-231 and HeLa cells, maybe due to the concentration of metabolites exerted by solvent. Previous results report that compounds such as taxifolin and procyanidins, the most abundant present in each of the extracts, play a fundamental role in their cytotoxic activity, inducing apoptosis on upregulating the expression of the proteins in HeLa and MDA-MB-231 cells (Amalinei et al., 2014).

Table 3 IC50 for P. durangensis and Q. sideroxyla bark

extracts on cancer cell lines and non-tumorigenic cells.

Tabla 3. IC50 de los extractos de P.

durangensis y Q. sideroxyla sobre la

viabilidad de líneas celulares cancerosas y no tumorales.

| Cell lines | ||||

| Extract | IC50 µg/mL | |||

| HeLa | MDA-MB-231 | HSF-1184 | MCF-10A | |

| P. durangensis CE | 210.30±6.75a | 77.34±4.06a | ND | ND |

| P. durangensis OE | 201.50±٨.٢٩a | 37.49±0.95c | ND | ___ |

| Q. sideroxyla CE | 184.03±7.83b | 46.83±0.73b | ND | ND |

| Q. sideroxyla OE | 103.64±3.87c | 32.82±5.54c | ND | ___ |

ND: not detected within the investigated concentration range. Means ± SD in each column followed by different letters are statistically different by Tukey test p≤0.05.

The abundance of catechins and the synergy with other metabolites within the phenolic profile of Q. sideroxyla could be why it showed the highest cytotoxic activity compared to P. durangensis. In addition, there is evidence that flavonoids that possess C2-C3 unsaturated bond and a carbonyl group at position 4 exhibit lower IC50. These two functional groups may increase the compound’s activity by affording more stable flavonoid radicals via conjugation and electron delocalization (Sadeghi-Aliabadi et al., 2012).

Several investigations reported cytotoxic effects of some Pinus and oaks species on different cell lines that were related to compounds with the biological activities (Şöhretoğlu et al., 2012; Li et al., 2016; Moradi et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2016; Amessis-Ouchemoukh et al., 2017; Sarmeili et al., 2017).

Conclusions

Quercus and Pinus species studies are intense due to their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and anticancer potential; however, studies on the phenolic profile is scarce, and is associated with the reported effect. This work demonstrated that the phenolic profile and the concentration of specific metabolites such as the procyanidin dimer of catechin/epicatechin compounds was determinant in the cytotoxic activity evaluated in the cell lines used. Q. sideroxyla OE showed a potent cytotoxic activity compared to CE and OE from P. durangensis. This strong cytotoxic effect represents an opportunity for the valorization of the wood industry by-products, suggesting that OE of Q. sideroxyla may represent a good alternative in the search for new agents of natural origin to treat mammary and cervix cancer. Nevertheless, more in vitro and in vivo studies are necessary in order to understand and establish the mechanism of action.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)